Enculturation

“I think that if I was to choose to have a conversation with a young boy with a high voice than a teenager with a boring voice, perhaps like mine at the moment then I’d certainly pick the boy’s voice because it’s a much more dynamic and interesting voice to listen to.”

William, aged 15.

“I don’t want to be like this big tough adult person, I just want to be a cambiata I, so then I can actually suit my throat because I don’t want to sing really high where I get cracks and breaks in my voice, I want to stay low so my voice is better.”

Harry, aged 14.

Introduction

In the previous chapter we looked at three young men who had a good idea about what they wanted to sing and who exercised a considerable degree of agency in determining how they were going to sing it. Although they were divided by the question of how high boys should sing, they were united in their commitment to the output of “dead composers”. Nathan, through “years of proximity to it” knew that he was “gonna like it”. Cai, it will be recalled, was not going “to do some crazy pop thing”. Eric referred to levels of emotion generated by the repertoire for a voice that would not be used in popular music and faced the prospect of an unusual, specialist career.

In this chapter we are going to look at boys in middle adolescence who are free to sing in the comfortable, full range of their voices, unconstrained by the need to fit the voice to a recognised choral part. Through further case studies, I will demonstrate that the musical environment of childhood is a critical factor in determining the willingness of adolescent boys to engage with “dead composers” once their “treble” voices are lost. We shall see that solo singing offers opportunities not available in choirs and focus particularly on a song that showcases voices in the first stages of change. Looking forwards to the final part of the book I will draw attention to the fact the mean or medius parts of renaissance times are very similar in range to the cambiata parts devised by Irvine Cooper. For a good many living boys, the mean part might fit their voices more comfortably than the more familiar treble.

Socialisation and enculturation

The commitments to “dead composers” evident in the previous chapter are the result of the process known in anthropology as enculturation. The anthropologist Margaret Mead, back in 1963, drew a seminal distinction between enculturation and socialisation. Socialisation has to do with ‘the set of species-wide requirements and expectations made on human beings by human societies’. All boys need to undergo socialisation and I suggested in my introduction to this volume that choirs are good environments for socialisation. Enculturation, however, takes us a step further. Enculturation is ‘the process of learning a culture in all its uniqueness and particularity’ (Mead, 1963).

It is the particularity that explains the affinity with “dead composers” shown by our three young men. Of enculturation, Lucy Green wrote:

By ‘enculturation’ I mean immersion in the music and musical practices of one’s environment. This is a fundamental aspect of all music learning, whether formal or informal. However, it has a more prominent position in some learning practices and styles of music than others (Green, 2003).

Green argues for the informal learning styles of popular musicians. Whilst I have long believed that her pedagogical analysis of how popular musicians learn is sound, perceptive, and useful, I have also believed that in her assertion that “it has a more prominent position in some learning practices and styles of music than others” she may perhaps be overlooking a point of considerable importance. It is true that a boy in a cathedral choir is likely to attend a school where subjects such as music theory and music history are taught in the formal way of which Green is implicitly critical, but this is not how our young men learned the skills of high-level participation in choral singing.

We have heard that both Cai and Nathan learned initially through imitation of the older boys in the choir and later through the imitation of solo artists. I have heard the same story from most of the other boys I have studied. The choir of a cathedral, college or greater church of comparable musical standing is a place where, in Green’s own words, boys are “immersed in the music and musical practices of [their] environment”. What goes on in their schools is often of rather less significance, as I learned early on in my research programme:

The quality of the singing is terrible and they only have words. No music. They just teach us the melody and we don’t sing in parts. The irony is that the boys who want to be in the choir can read music. They just sing tacky musicals. I prefer proper choral singing (Y7 boy in chorister group interview, in Ashley, 2002: 261).

This, in a school where there is at least an attempt at singing.

These are boys who learned to read music through following scores from the age of eight whilst copying their elders in the choir. Like Nathan, they have had “years of proximity to it” and know that they are “gonna like it” for the rest of their lives. In other words, they have become encultured. On this point, Eric parts company with Cai and Nathan. Cai and Nathan have been encultured into current choral practice, learning from their respective practising communities. Neither nominated a particular vocal hero. Eric does not belong to such a close knit community wanting instead, since the age of at least nine, to be like his hero Derek Barsham. One cannot really be encultured by an individual. As I pointed out in my conclusion to the previous chapter the prospects for a whole choir of boys singing like Eric are few. Were such a choir ever to come into being, it might be viewed as an historical project, an attempt to recreate a choral culture from which the world has moved on. I look at the prospects for this and similar ventures in a later chapter.

If in doubt, mime!

Hitherto we have focussed on individual boys. Like many others, Cai is known as a solo artist, but his enculturation took place in his church choir in Surrey. Almost all boy solo artists have had connections with choirs at some stage in their careers. A fundamental issue that we need to grasp at this point is that in choral singing, voices must conform to choral part ranges. Any boy who decides to leave his choir in favour of a solo career liberates himself from this constraint. I have encountered several such boys in my longitudinal studies.

To a degree all singers face some compromise in making their individual range conform to a recognised part range, but when the singer is an adolescent boy, we are into unique musical territory. This is reflected in the popular collection by Hobbs and Campbell (2012) Changing Voices: songs within an octave for teenage male singers. The songs have a range of no more than an octave and they can also be transposed at will into the most suitable key during the singing lesson. This will work for almost any boy with good experience of singing, but if either of the above conditions is violated, some form of compromise will likely be needed. Alan McClung puts it like this:

It would be grossly inaccurate to assume every voice precisely fits the prescribed range boundaries of a singer’s assigned category. On an individual basis, each boy is experiencing a vocal transition. However, it is can be assumed that a large majority of singers can manoeuvre vocally within the appropriate ranges designated above (McClung, undated).

He is here talking about the cambiata system which is founded upon Irvine Cooper’s tenet that the “music must be made to fit the voice, not the voice the music. The “manoeuvres” of which he speaks can often amount to little more than miming notes out of reach. There is no shame in that – indeed, boys in choirs need their conductor’s “permission” to do so, though I am not sure that it applies quite to the extent of the Y8 boy in the Oxbridge collegiate choir who could manage only a baritone voice during my visit.

You’re still in the choir?

Yes.

What do you do?

I mime.

Singing out of range

A boy is in range if:

- He can sing efficiently for sustained periods without fatigue

- He is untroubled by lift points or pitch breaks which he finds difficult to manage.

It is hard to believe that the Y8 Oxbridge boy above attended every rehearsal and service without ever singing a note, but by these criteria, he would clearly be singing well out of range whenever he attempted to join in with the other trebles. This would not have been a situation likely to continue for more than a few months as he would have left the choir at the end of Y8, but the extent to which there is out of range singing in choirs where the belief is that “all boys are trebles” may be greater than is often recognised. The cambiata system was devised to overcome difficulties such as this but suffers from the huge drawback that “dead composers” did not write for cambiata choirs.

We are seemingly in a very difficult position here. On the one hand, most enculturation takes place in SATB choirs. On the other, most out of range singing by boys old enough to be starting to make their own decisions also takes place in such choirs. Perhaps we need to look again at the statement dead composers did not write for cambiata choirs. There are some critical points to consider.

- The present day pitch standard of A = 440 Hz is of relatively recent origin. Though first proposed in 1834, it did not come into widespread use until the 1930s. Before then, pitches were generally lower. 435 Hz was common in nineteenth century Europe. Baroque pitches were lower still. 415 Hz and 392 Hz are sometimes quoted, though these are modern day technical conveniences. A more likely reality is that pieces were performed at whatever pitch worked for the available instruments at the time. The only thing about which we can be confident is that this would have been lower than present day performance uninformed by historical scholarship.

- Sixteenth century pitches were lower still and not infrequently set by the available voices rather than an instrument tuned to an absolute reference standard. It follows that we need to know more about what kinds of voice were available.

- The majority of boys alive during the golden age of choral polyphony did not sing treble in any case. The lower boys’ part of “mean” was the more common. Even that is a simplification, since mean ranges differed before and after the English Reformation. I explore this fully in a later chapter, but there can be little doubt that pitches were often too low for currently living boys with unchanged voices.

If these points come across as in any way radical, it is because we are perhaps resigned to the fact that we cannot create a living human in the way we can create a musical instrument through careful research into period materials, techniques and practices. Some adult singers, more often professionals, do of course go some way to specialising in period performance, but this is rarely done with living boys who are just assumed simply to be “trebles” (meaning mezzo sopranos at A = 440 Hz in most cases) regardless of how far they are through puberty.

Theoretically, in a system such as Cooper’s cambiata, there should be much less out of range singing than is found in choirs where all boys are “trebles”. In practice, though, I have found this not to be the case. The cambiata part is often sung by stage 4 boys, which is not what Cooper intended. Alun McClung describes the situation thus:

Boys whose voices are in the second phase of change (having been classified as tenors) [are] mixed with boys whose voices are in the first phase of change (cambiata). This practice severely limits the vocal potential of the cambiata because music must be chosen which seldom goes higher than an E flat or F above middle C and he is never allowed to use his upper voice which contains some of his most beautiful tone (ibid., my emphasis).

Who are these boys who are “never allowed to use their upper voices that contain some of their most beautiful tone”? The answer I am going to give here is that they are the boys who in the sixteenth century would have been means. In that sense, “dead composers” did write for cambiata choirs. They wrote for the voices, even if they wrote music of a different genre for a different purpose. Cooper’s idea that “the music must be made to fit the voice, not the voice the music” was a radical one. We need to consider another perhaps even more radical one. If we want to hear the vocal timbre that many of the “dead composers” heard, we should not be dismissive of approaches which result in boys singing in the cambiata range. The modern day “treble” may not be the most suitable voice for historically informed performance of significant portions of the repertoire.

Was cambiata really novel?

In the final part of the book we shall see just how relevant was the first part, where we looked at matters such as growth during puberty and long-term secular trends in stature and pubertal timing. First, though, we must look more closely at the cambiata system, particularly the issues identified by McClung above.

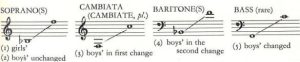

There have been all sorts of revisions to the cambiata system over the years, some of which have made it more complicated or “fussy” than it needs to be. The figure below is taken from Cooper’s original 1965 publication and shows how he understood it and what he intended.

Cambiata here are simply “boys in first change” for which we might read “in-puberty”, explained in Chapter 3 of this volume as Tanner stages 2 and 3. A direct correspondence to Cooksey’s two midvoice stages is readily seen. Boys with singing experience should be able to cover the whole cambiata range as they go through midvoices I and II. Some may begin to struggle with their “devil’s note” (somewhere around E4) as they approach the end of the phase, which is why a Cambiata II part can be provided (range E3 – E4).

“Cambiata” then simply means the early stages of change, before the rapid voice deepening that takes place during the high mutation stage (midvoice IIa or stage 3) when transition to “completing puberty” begins (the “second change” for Cooper). Often, however, cambiata is not interpreted as this “first change” but as the “second change”, i.e. stages 3 and 4. In other words, those awkward to place boys who in the SATB system really can’t sing “treble” any more but who are not ready to join the adult tenors or basses either. Such boys are frequently misclassified through allocation to the tenor line before they can sing C3 (“tenor C”). This is when they should be on the Cambiata II part which does not go below E4 where the voice rapidly loses power and begins to croak, or above the troubling E5 region where it might “crack” into the new M2 register. Equally, and particularly given that progression through stage 3 is usually fairly rapid, there are what Cooper called “boys in the second change” found singing cambiata parts when they might actually be better as “new baritones” or even “tenors”. Such boys may be referred to as “first tenors”, although their voices and range will be different to adult members of a TTBB chorus (Ashley, 2022).

These difficulties happen because the SATB system and the cambiata system are simply not compatible, which is why the cambiata system was devised in the first place. Boys with changing voices do not fit SATB parts! The real casualty in all this misplacement, however, is the mean, (or meane/medius to avoid confusion with statistics) for which read “boys in first change”. Taking up McClung’s point, we rarely hear the beautiful tone of which the mean voice is capable because it does not belong anywhere in the A = 440 Hz SATB system.

I explore this in much greater depth in the final section of the book. In the remainder of this section I want to look at case studies of living boys who, of their vocal agency, have chosen to sing in the mean range, even though the term itself was unknown to them. The great irony is that none of these boys is found in an ecclesiastical choir, the very kinds of institution that enculture boys to perform works of “dead composers”.

What is a good mean voice?

The term “mean” is rarely used today but if there is ever to be a serious attempt at historically informed performance by boys, a better understanding of what means were and how means might have sung is going to be needed. In Chapter 9 I evaluate some performances of choirs that have used boys as means. They are rare, but they do exist! In the last part of this chapter I am going to look at some case studies of boys I think could have been good means.

Before the English reformation, meane or medius parts, as far as we can tell or transcribe to modern scientific notation, most commonly ranged from G3 to C5, sometimes as low as E3 though never higher than D5. This is well illustrated in Magnus Williamson’s recent edition of the Sheppard Magnificat, which can be relied upon as a scholarly reference source.

The similarity of medius parts such as this to Cooper’s cambiata part can hardly be total coincidence.

In selecting a living boy who would have a good prospect of rendering this well, one would surely select a cambiata boy, that is a boy in midvoice I or II. There is also a higher triplex (treble) part that ranges from E4 to G5. For this we might select an unchanged voice or perhaps a midvoice I. After the English reformation, both of these parts were merged into a single mean part with an undemanding range of C4 – D5, which could be sung by any competent living boy whether unchanged or midvoice.

I consider this issue in detail in Chapter 9, but I now want to look at living boys from my database who could sing a medius part, perhaps to an exemplary standard, were they so inclined. Unfortunately, none was. That is the challenge that is faced!

May it be?

The song May it be was composed for the film Lord of the Rings. Combining elements of classical, folk and world music, it might be classified as “new-age”, so its performance by an ecclesiastical choir might be relatively unlikely. It is one of those songs, however, that regularly attract high-calibre boy recording artists. It was originally recorded by Enya, in the range A3 – B4, comfortably in the tessitura of what, for a boy, would be midvoice. Howard Shore, director of the recording, is on record as saying “I wanted Enya’s voice”. However we might categorise the timbre of Enya’s voice, one word we would not use would be “countertenor”. The significance of this observation will become apparent later.

Dominic (stage name “Inigo”) recorded the song in 2005 for his album My World. Dominic had been a chorister at Chester Cathedral but left the choir after working with the London singing teacher who was preparing him for various recordings and auditions. The teacher did not approve of the “head voice” he was required to use as a “treble” in the choir, so this was another example of the kinds of clash that arise regularly between singing teachers and choir directors. It is also a example of the fact that, in spite of this, most successful boy recording artists begin their careers in choirs, most commonly ecclesiastical ones.

It was obvious to me that Dominic was in midvoice at the time which was why I was keen to engage him for the Boys Keep Singing project as an example of a cambiata voice. He recorded several items for us, including a complete film on voice change (Ashley et al, 2007).

May it be (Dominic)

I made much use of his recording of May it Be in the work on vocal identity I was undertaking at the time. I was enthusiastic as I had what I considered to be a very good cambiata voice that I felt could be a model for other boys, or indeed for teachers and conductors working with boys. A point that needs to be appreciated is that Irvine Cooper had considered the voice of Wayne Newton to be a good example of “cambiata”. This I have always thought odd, since Newton experienced an unusually protracted puberty, voice change not completing until his mid 20s.

Wayne Newton, aged 20. Cooper’s prototype cambiata

Dominic, in contrast, experienced a completely “normal” puberty. Indeed, by the time of the filming he had progressed to stage 4 and recorded a “pop” song called This Week’s No. 1. That, however, is another story.

His cambiata voice was frequently identified as female by peer audiences. In that sense the recording was a success since it sounded more like Enya than a countertenor voice. A twelve year old chorister at a prestigious cathedral successfully identified it as male and was moved to say simply “because it was lovely”. Had the voice been used for a verse part such as Gibbons’ Record of John (see William in Chapter 6) the views of other boys with knowledge of Tudor choral repertoire would have been interesting. However, peer age listeners in ordinary schools who knew the song compared it unfavourably with Enya’s performance, so the main objective of demonstrating cambiata to thirteen and fourteen year olds could not in that sense be said to have been achieved.

Harry did not record May it Be commercially, but willingly submitted himself to being “experimented” on as part of my endeavours to build upon what had been learned from using Dominic’s performance for Boys Keep Singing. Harry’s principle interests had not been singing but modelling and acting, which he undertook professionally. However, he had joined ABCD’s cambiata choir and was studied longitudinally between the ages of 13:09 and 15:02. Puberty had begun by 13:09 but the main events were yet to come and occurred from the age of 14:02 onward. SF0 between ages 13:09 and 14:02 remained at around 214 Hz, with a lowest comfortable singing note of A#3. This was the period during which the work on May it be was undertaken. He self identified during this time as a Cambiata I voice.

erm, well, like you said, I don’t want to be like this big tough adult person, I just want to be a cambiata I, so then I can actually suit my throat because I don’t want to sing really high where I get cracks and breaks in my voice, I want to stay low so my voice is better.

Selecting the best key for May it be held certain challenges. We initially chose Ab, making the range Ab3 to Bb4. This was on the grounds that Ab3 had been identified as his range bottom, thus in theory making the widest possible range available. However, I felt the Ab was weak. It was some 10dB lower in power that the tone above, so we tried it up a tone in Bb, making the range Bb4 – C5. This time the lower notes worked really well, but Harry struggled with the C5.

Now, tell me about that C. It looked painful. Your chin was pushing out forwards, which is a classic example of tension. How did it feel, that C?

Um, hurtful.

Hurtful? And you know why? It’s because we’re at the very top of the working limit of your lower register. . . It doesn’t want to go. But I took you into head voice earlier.

Yes you did.

Yeh, let’s see if you can do that again. Sing me that C.

(sings, haaa)

See if you can get that top G again.

(Sings, laaa. Sounds very breathy but on pitch.)

Now sing me the E

(sings, aaa

The G

(aaa

(sings 5 note vocalise G5 to C5. Accurate, but weak and breathy)

Harry’s case is particularly instructional as it encapsulates perfectly the situation of a boy in midvoice II who has never been trained to use a chorister “head voice”. Cooksey states that falsetto and whistle registers emerge for the first time at this stage and the “transition zone (passagio) between modal and falsetto registers was F4 – C5” (Cooksey, 1992: 57). This was exactly what had happened to Harry. His voice was wanting to transition in this region and by the time the C5 was reached it was “hurtful”. He could go no further because he had received no training or practice in the necessary technique, although the notes were there right up to G5. A trained chorister could have produced good tone between C5 and G5 through maintaining a higher CQ (see Chapters 5 and 6). There would be no point in working on this with Harry since at 14:02 he was on the cusp of midvoice IIa and relatively late at that. His agency was “to stay low so my voice is better”.

Soon after this period, Harry went through the remaining stages fairly quickly, SF0 fell to 174.5 Hz by 14:05, to 134.5 Hz by 14:08 and 107 Hz by 15:02. It was then that his voice “broke” as predicted by catastrophe theory. He had successfully auditioned for the part of Tommy in a professional production of the Who musical of that name. Knowing how quickly he was now growing I questioned the wisdom of the producers, although I didn’t confide my doubts to Harry. The subsequent events are best told in his own words:

Well, in Tommy we had to do a bunch of rehearsals, learning how to sing and all that stuff.

Yeh, yeh, yeh, yeh, yeh. I want to know what happened to your voice Harry!

Oh. Ah! When I did my audition my voice was really high, like I could sing the high notes but when the show actually began my voice broke.

It did what?

It changed.

It changed. Just in the middle of the show?

No, not in the middle of the show. When were rehearsing and trying to get those singing bits right. I tried to sing the high bits, but then my voice actually broke.

It just wouldn’t come out?

No

So what did the producer or musical director do?

What the director did was he got two other boys, two whose voice hadn’t changed yet, and they did a recording of the high bits and we just had to sing, we had to just lip sync the high bits.

Right, so you mimed it?

Yup.

Did you do any singing at all? Did you sing in the lower part of the range?

No because it was a ten year old and a four year old, so, so when the music director actually heard me speak, we can’t have it because it’s like a ten and a four year old.

You, Harry, were playing the part of a ten year old?

Yes I was.

A great hulking ugly teenager playing a cute little ten year old?

Yes. Because I was very small at the time but then I grew. So I was the best person to play it but then I grew. Really big.

That’s exactly what happens at your age!

Yes!

Cormac. Unlike Harry, Cormac had chorister experience, having begun his career in Manchester Cathedral and the Hallé youth choirs just before the Covid lockdown changed the course of events. He recorded May it be at the age of 12:06. The range was an untaxing A3 – B4 which could be sung equally well by an unchanged voice, midvoice I or midvoice II. Whilst to some ears the voice may sound unchanged, at age 12:06 Cormac was on the very cusp of voice change. He had just experienced the “pre-adolescent dip” in height velocity to only 2cm per annum. By age 12:10 it had peaked at 9cm per annum before settling to between 7 and 8 cm per annum until PHV of 11.9 cm per annum at age 14:01. The nearest available SF0 was recorded a month after May it Be at age 12:07 when it ranged between 195 and 225 Hz in an interview for the BBC. We may thus deduce that what we are hearing here is an early midvoice I, less mature than Dominic’s but nevertheless into change.

May it be (Cormac)

We discussed Dominic’s performance of May it be, and I asked Cormac to read something I had written. “Boys can be similarly divided into those who approach the turning point aware that their voices are changing, and those who are happy to ignore any signs until they do feel discomfort or their voice actually “breaks”.

Which one are you?

The aware one

Tell me what cambiata is.

Er, a changing voice, that hasn’t changed fully.

In terms of things like bass and treble and soprano, where would you put cambiata?

It’s different.

In what way? Where does it sit?

All of them.

MMmm. Remember at the moment you’re singing alto in the school choir, you’re not really an alto.

I’m a tenor.

Not really.

I’m a bass! (laughter)

You’re somewhere between…

Yeah alto and tenor

That’s cambita.

Oh OK.

The thing is, Dominic didn’t know that. Is that true of you? Did you record May it Be without realising the pitch you were singing it at was cambiata?

I would have said, probably alto.

A low or “second” treble might have been the most accurate of all descriptions of the A3 – B4 range, a point made by Cormac’s mother. We would not, however, call Enya a “treble”. Adult audiences for boys’ voices are niche and have different expectations to peer group audiences, hence the latter’s criticism of Dominic’s performance. As far as mainstream culture is concerned, there needs to be a specific reason to employ a boy’s voice. James Rainbird’s Suo Gan for the film Empire of the Sun would be an example, as would Cai’s recording of the same song for Pembrokeshire Murders.

Relative to most boys I see, Cormac was quite well-informed about voice change. Harry was also knowledgeable through being a member of a cambiata choir. He understood and recognised cambiata as his identity, yet fell victim to a music theatre production team that made what can only be described as elementary errors. Dominic knew that he did not wish to remain a chorister but placed all his faith in a singing teacher who apparently just told him what to do without providing a wider context. Whether their histories would have followed the same course had the option of being a mean is something that we need to address. It would not be unfair to say that, aside from a few notable exceptions, the choral world is rather poor at explaining to boys what their options are as they approach puberty. The majority know neither the term cambiata nor the term mean.

Does enculturation endure?

I have touched on the challenges of the identity transition that is inevitably closely associated with voice transition. We have considered briefly the nature of the teenage brain and we have devoted slightly more space to the process of enculturation. We have seen evidence that enculturation can be a powerful force, powerful enough to maintain a childhood affinity with “dead composers” during the turbulent years of middle adolescence. However, these are also the years when young people have always looked beyond the routines and confines of their childhood. In this present age, their teenage brains must also cope with the twenty four hour onslaught of social media. The two forces of social media and music streaming can expose boys to a range of genres and performers unimaginable to their forbears.

At the age of 15, Dominic, a former cathedral chorister, recorded a “pop” single in a commercial studio with professional imaging. The main technical point to note is the location and range of the tessitura, a fifth from A3 to E4.

This Week’s No. 1 (age 15)

I cannot in all honesty say this this is one of my favourite songs. Boys I have played it to have identified the lyrics as sexist, so I think I can rely on their opinions without expressing my own. It is, however a very skilful placing of the voice that avoids any of the problems that will be encountered by a fifteen year old attempting “classical” repertoire (see Max below).

In Dominic’s case, enculturation had not endured and looking back on the Boys Keep Singing project some fifteen years later I have cause to reprimand myself for implying that if you want to become a rock singer, you have to start as a treble chorister. It is certainly true that the musical skills learned as a boy chorister are one of the best foundations to be had for any career in music, but it was not really in the spirit of “dead composers and living boys”.

Cormac, I could see, was also losing interest in “dead composers”. His formative years in Manchester Cathedral had not been particularly happy ones and he did not return to that type of environment after the Covid lockdown. At the same time, his social media and music streaming profile as a developing young artist was what provided him with the experience and reward that a school environment could not. I recorded the following interview with him when he was aged 13:09.

What’s cool? How do you choose repertoire that is cool?

Er (pause) I don’t know. What d’you mean?

Don’t you know what cool means? Is that word not used anymore?

Yeah! I’m cool!

Well, you’re cool, obviously! We can see that! But how do you choose cool repertoire? What repertoire, songs to sing. . .

Well, it’s opinion isn’t it? I could think that one song I’m singing is cool and then some absolute person who does not know what they’re talking about says Oh Cormac you sing opera. What are you on about!? How is Bright Eyes by Simon and Garfunkel opera? And how is Run, by Snow Patrol, like a massive rock band….(splutters and pauses) Opera!!

Are they cool songs?

Yeah! (emphatic)

Why do you think they’re cool?

Because Snow Patrol’s cool, and it’s their song.

Why are Snow Patrol cool?

Er, um ‘Cos they’re a rock band? (rising inflexion as though it ought to be obvious)

And rock bands are cool?

Yeh

Have people accused you of singing opera?

Yes. I’ve never sung an opera song in my life.

Who’s accused you of singing opera?

Mostly people at school. Oo Cormac don’t you sing opera? No!

Why do you think they say that?

Because they’re clueless? And because it’s a slightly classical sound to it so they think it’s opera. They should hear opera compared to what my songs actually are.

They might like it!

Eeuh. I hope not.

His comments about opera reflect accurately a situation I have encountered many times before. His observation that a “slightly classical sound”, particularly when produced by a boy’s high voice, will be written off by peers as “opera” are fully supported by research in diverse school environments (see Ashley, 2007; 2008; 2009; 2010). His explanation that “they are clueless” is not one I would make as a sober academic, but I am not going contest it. Rather, I am going to reproduce it as a comment on the way things are by a young student with more knowledge than most.

Cormac’s accelerating drift from the dead composers is partly explained by a combination of weak enculturation and Covid disruption, but his desire to develop originality as a young artist has freed him from the restrictive conventions of the classical music world. At the time of writing, his second album has just been released. Whilst most of the tracks are midvoice I or II, the last two are in his “new voice”, in other words his stage 4 emerging baritone. Like Cai, he was silent in public during the midvoice IIa stage which, as is often the case, was short-lived. SF0 fell from 185 HZ at the time of his last live public performance at age 13:07 to 133 Hz at age 14:03 when he first ventured to perform in public again. This was a tentative venture with the local Salvation Army in July 2023 at the age of 14:04. The YouTube video received only 17 views, but the midvoice IIa silence had been ended and the following professional recording with Dominic Ferris appeared only a few months later when Cormac had found and developed confidence in his “new voice”. This recording is in an entirely different class and is perhaps the one that continues his career now that the SF0 has fallen to 121Hz at 14:05 and 114Hz at 14:08.

Country Road

Country Road ranges from C3 to D4 and fits comfortably what has turned into a secure new baritone voice. It reflects the Cormac I have come to know and thus has an integrity not be found in contrived mid-adolescent “pop”. There is every reason to believe that his new voice could in time surpass his former treble voice. Where he will be as a young adult is difficult to predict but to suggest, like Bairstow, that there is “no use trying” in the mean time is quite wrong. This is an issue that the the classical music world cannot afford to ignore. Indeed, I am very happy to listen to Country Roads in its own right, and equally the two new voice pieces in his second album. I rather like all three!

I am going to conclude with cases of boys studied earlier on who are now young adults. We have already heard from Nathan, who at the age of twenty was president of his University’s choral society, maintaining his interest in “dead composers” as well as experimenting with various rock genres. Max, also twenty, has returned to classical singing, indeed an interest in opera, whilst William is making his way as a professional organist.

Max was interviewed in depth at the age of sixteen, and again very recently at the age of twenty. A week before his sixteenth birthday he had come to my studio to record Schubert’s An die Musik for his music GCSE examination, which he had previously recorded as a “treble”. He had forgotten his former voice to the extent that he could not even recognise it when listening to a recording of the Christmas hymn See Amid the Winter’s Snow. During this he and three of his contemporaries had sung solo verses. He said that he could recognise their voices, but not his own. His reaction when I played him the recording from his Monday Afternoons CD album of An die Musik was even more remarkable. He had not, at age 16, listened to the album since we had made it. I quote his exact words:

(spontaneous laughter/incredulity) That’s not me, that’s not me!

I promise you, it’s you.

I genuinely sound like a girl!

No you don’t!

I discussed with him my research finding that both boys and girls in school aged between ten and fourteen often confused boys’ and girls’ voices, not because of similarity of pitch but because of the belief that “boys can’t sing that good” (Ashley, 2022).

One of the reasons you chose the piece to record for your GCSE is it’s actually a grade 8 piece, so at the age of barely 12, I think you were only eleven and ten months when you made that, at the age of barely 12 you were effectively taking a GCSE, which rather flies in the face of boys can’t do it.

Now that is interesting because you said there that I chose this piece because it was grade 8, but I didn’t choose this piece because it was grade 8, I chose this piece because I know this piece because I’ve been doing it for so long.

Like may former choristers, Max was able to draw upon his childhood learning to pass a GCSE music examination with ease. However, soon after came the Covid lockdown which was to prove a difficult time for so many young people, Max being no exception. For one thing, immersion in the music and musical practices of live communities was abruptly ended. For another, A level study had to be conducted on-line. Other events had made the period a particularly difficult one. That Max contacted me at the age of twenty to “do some singing” is significant. He arrived at my studio wanting to record Schubert’s An die Musik yet again, and Donizetti’s Come Paride vezzoso. His interests had changed from medicine to to engineering, but his early enculturation had endured and he had returned to a musical community in the form of the Huddersfield Choral Society where he had successfully auditioned for a choral scholarship. And he wanted to sing opera!

Interestingly, he had also regained interest in his treble album, mainly through finding songs from it uploaded to social media by “boy soprano lover” and other similarly minded individuals. I learned during his stay that one particular community had played a part in his choral rehabilitation – the Morland Chorister Camp. Max had attended this as a boy where he had enjoyed not only a rich musical environment, but one of camping and the damming of streams (a Morland speciality). The camp, like so many choirs, had suffered badly as a result of Covid but was now recovering well and Max had returned as an adult helper. If there is any doubt that investment in boys is necessary to secure a supply of adult males interested in performing works of dead composers, cases such as this should go some way to dispel it. I was interested to learn from Max that when the choir was presented at Morland with a score marked “triplex, medius, contra-tenor, tenor and bassus” everybody said “what’s a medius?” and the altos asked “what part do we sing?” The living boys exist, but there is work to be done!

The three recordings of An die Musik at ages eleven, fifteen, and twenty are a valuable resource for any student of voice change and John Cooksey. The main point to note is that the recording at age 20 in the key Db of is higher than the one at age 15, which is three semitones lower in Bb. The note of particular comparison is F4 on the word Welt, 16 bars or 35″ in the 20 year old version. This is stronger and richer in higher partials that the lower Welt on D4 at age 15 (30″ in), which sounds a very weak “schoolboy bass” in comparison. It is not the ability to reach low notes that marks the development of the voice in late adolescence, but the highest notes. Neither Cormac nor Dominic at ages 14 and 15 respectively had ventured beyond the comfortable range of their modal voices.

Age 11

Age 15

Age 20

William also took part in an extended video interview at the age of nearly sixteen. Like Max at that age, memories of his treble voice had rapidly faded and recordings such as Benjamin Britten’s Corpus Christi carol which we had made when he was thirteen had been forgotten. In this case, the first recording I played him was of his speaking voice at the age of eleven.

It’s quite spectacular. I wouldn’t have thought that at any time it would have been that high. I certainly can’t remember being able to speak that high. It’s been such a gradual thing that I’ve got used to the voice I’ve got at the moment, so, but it’s certainly a massive surprise.

But you said something a minute ago, did you say it was a more interesting voice when you were eleven?

Yeah, it certainly is. I think that if I was to choose to have a conversation with a young boy with a high voice than a teenager with a boring voice, perhaps like mine at the moment then I’d certainly pick the boy’s voice because it’s a much more dynamic and interesting voice to listen to. There’s more variation with the pitches and expression with what the person says.

This is a rare and fascinating perceptual comparison of child and adolescent voices in which William perhaps recognises the acoustic phenomena described by Cooksey as well as the teenage retreat from prosody. I then played him a recording of the Welsh Lullaby Suo Gan that I had made with him when he was aged eleven. This was his reaction.

Well it was a big shock to me. I wasn’t expecting the tone quality that I heard.

A good shock or a bad shock?

Oh well a good shock, certainly. It wasn’t the voice which I remember having when I was a treble.

So you’ve forgotten it very quickly then, haven’t you?

Yeah I’ve got used to the one I have now. Although I miss that time very much it’s something I can’t have back, so I’ve got to carry on with the one I’ve got.

Like many ex-choristers, William’s enculturation has resulted in a focus on organ playing rather than singing. At the time of writing, he is in his mid-twenties, studying at the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique et de Danse, Paris and a highly proficient organist, specialising in French music played on Cavaillé-Coll organs. Later in the same interview, I played him the recording we had made of This is the Record of John, described and analysed in Chapter 6. I have always felt this a beautiful sound, perfect for the voice at the stage of change it had reached, but in this instance, William’s enculturation was an obstacle. He seemed to think that it was not proper for a boy to sing an alto verse and that only an adult countertenor should sing it. Presumably at some stage, if it has not happened already, William will encounter the literature and perhaps performance practice that questions the role (or not) of adult falsetto voices in Tudor church music (See Ravens, 2014 or Parrott, 2015, for examples). Indoctrination is too strong a word. “Enculturation” describes more appropriately the process through which William developed his attitude and beliefs toward the present-day practice of employing adult countertenors almost universally in English cathedral choirs.

The difference is that the encultured progress in their understanding whilst the indoctrinated are frozen in their prejudice.

Key points to take away from this chapter include:

- The musical environment of childhood plays a key role in the development of adolescent values and attitudes towards “dead composers”.

- Out of range singing is common in choirs but can be managed.

- The term “cambiata” is sometimes misunderstood. Irvine Cooper equated it with the early stages of change – Cooksey’s midvoice I and II.

- Boys at midvoice I and II in the UK more commonly remain on treble lines, so cambiata voices are not often heard in choral singing.

- The Cambiata II range of E3 – E4 matches the midvoice IIa voice, but boys in choirs at this stage are often put on tenor parts where they cannot reach the bottom of the range.

- Solo voices are more likely to sing within range when they do not have to fit a choral part, either in singing lessons or the recording of albums.

- The cambiata ranges closely match the mean ranges of renaissance times. It is plausible that sixteenth century means were cambiate, which raises exciting possibilities for historically informed performance.

- Strongly encultured boys rapidly forget their treble voices during middle adolescence but retain their interest in the works of “dead composers” sung during childhood.

- The classical music world could do a lot more to educate young people about singing ranges and voice parts in history and secure their interest.