Historically Informed Biology

The Cause of Changing the Voice, at the yeares of Puberty, is more obscure. It seemeth to be, for that when much of the Moisture of the Body, which did before irrigate the Parts, is drawne downe to the Spermaticall vessells; it leaveth the Body more hot than it was; whence commeth the dilatation of the Pipes.

Francis Bacon, Sylva Sylavarum.

Introduction

In Chapter 2 I introduced the idea that though ready access to digital technology makes scientific study of the voice possible to a level undreamed of in the twentieth century, much “traditional” practice with boys’ voices continuing to date from pre-scientific eras. In the previous chapter I introduced the historic mean or medius voice through an examination of what I believe to be its modern equivalent, the cambiata voice.

As far as living boys are concerned, the work of the voice change pioneers of the latter part of the twentieth century that culminated in John Cooksey’s writings represents the dawn of the present scientific approach. Irvine Cooper’s cambiata voice was, of course a product of this work but as I suggested it was not so much a completely new discovery as a rediscovery of voices that may have existed centuries earlier. In this chapter I am going to consider sixteenth century practice with boys’ voices. A rare record from Wells Cathedral, dating from 1460 entreats that:

The Master or Undermaster . . . should teach the boys clearly and distinctly in plain and prick song, taking care to give them high or low parts according to the range of their voice’ (In Watkin, 1941).

Was this the product of empirical knowledge or was it the result of some prescientific theorizing about the nature of boys and their voices?

Voyces Grave and Shrill

In writing of the sixteenth century, the word “shrill” tended to mean “high” with less of the connotation of unpleasant tone that we would associate with the word today. Francis Bacon explains in Sylva Sylvarum (1626), that “Children, Women, Eunuchs have more small and shrill Voices, than Men”. As voices lost their shrillness, they became “graver”. The “changing” as opposed to “breaking” voice was thus recognised by at least some contemporary writers. Moreover, it was associated with other characteristics of adolescence and puberty such as moodiness, impetuousness and “earnest affections” (much as known to Shakespeare). We read that both graver voices and what we now recognise as adolescent behaviour were the result of an excess of yellow bile leading to the body heating up.

They therefore that have hoate bodyes, are also of nature variable, and chau[n]geable, ready, pro[m]pt, lively, lusty and applyable: of tongue, trowling, perfect, & perswasive: delyvering their words distinctly, plainlye and pleasauntlye, with a voyce thereto not squekinge and slender, but streynable, comely and audible. The thing that maketh the voyce bigge, is partlye the wydenes of the breast and vocall Artery, and partly the inwarde or internall heate, from whence proceedeth the earnest affections, vehemente motions, and fervent desyers of the mynde (in Smith, 1999).

A “squekinge and slender” voice may have been misunderstood by some writers of our own age. The dramatic activities of the St Paul’s choristers between 1516 and 1590 and again between 1597 and 1613 have attracted much attention from scholars, perhaps more from the early modern theatre than the choral singing field. Quite possibly, the boys had more opportunity for singing during plays than services. Whilst liturgical singing would have been much constrained by the new protestant sensibilities, singing in the drama, according to Linda Austern (1992) ranged from polyphonic art song through consort songs to popular ballads.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, questions of singing technique and vocal colour have received relatively little attention from scholars of the early modern theatre. Some seem content with the assumption that the boys’ voices were “unbroken” and that as a result they sang “soprano”. Reavley Gair, in a now classic text, uses this term but it is simply not appropriate for the sixteenth century. Considerable significance, therefore, attaches to the approval given to the second contestant in a singing competition by Piero Sforza, the Duke of Venice who presides at the competition:

Piero: Trust me, a strong mean. Well sung, my boy.

The singing competition was a scripted event that occurs midway through Act 5 of John Marston’s play Antonio and Mellida. The script called for a “high stretched minikin” and a “good strong mean”. We do not know for sure the ages of boys who played the part of good strong mean. The one thing of which we can be reasonably certain is that their voices were well produced and did not “squeak”. A “high stretched minikin” could have been a particularly small boy. “Minikin” is defined today as a “very small, delicate creature”, “trivial and insignificant”. Assuming a similar meaning in the sixteenth century, this could refer to one of the smallest boys in the choir, perhaps the smallest available as a deliberate choice of casting. Such a small boy would certainly not be a “soprano”. He would simply be a child with a voice both unchanged and unskilfully controlled whereas the “good strong mean” could have been twelve or thirteen, perhaps at the midvoice I stage and with some experience.

There is, however, another meaning of “thy voyce squeaketh”. Ability to control the voice and avoid “squeaks” was considered a key indicator of masculinity in the sixteenth century. The boys who would be troubled by such a problem would likely have been nearer fifteen or so years of age. Not children, but adolescents struggling to be men and potentially the butt of much humour. Bloom appears to be very near the mark when she writes:

For in contrast to today’s audiences, early modern theatre goers had ample opportunity to hear unstable male voices. Whether the frequent enactments of squeaking voices in early modern plays point to a dramatic convention or offer evidence of a theatrical custom (that boy actors continued to perform while their voices were changing), there is much at stake in noting the role of these voices on the stage and in the culture at large. On stage or off, a squeaking voice announced a boy’s transition into manhood at the same time that it indicated that the transition had yet to be completed (Bloom: 1998:40).

There are many clues about sixteenth century boys’ voices if we know what to look for. Antonio and Mellida begins with an induction, during which the boys, as themselves, discuss the parts they are to play. Antonio exposes through the script the challenge that has been devised for him.

Antonio: I was never worse fitted since the nativity of my actorship; I shall be hiss’d at, on my life now.

Feliche: Why, what must you play?

Ant. Faith, I know not what; an hermaphrodite, two parts in one; my true person being Antonio, son to the Duke of Genoa; though for the love of Mellida, Piero’s daughter, I take this feigned presence of an Amazon, calling myself Florizell, and I know not what. I a voice to play a lady! I shall ne’er do it.

His misgivings, however, were probably not justified. Such a part would match the voice of a boy at Stage 4, perhaps aged sixteen or seventeen at the time. The fact that the boys discuss it is evidence that the phenomenon of their recently acquired falsetto speaking voice was well known and used to effect. In The Marriage of Wit and Science, also written for the Paul’s Boys, the actor who played Wit was evidently a gangling youth, mid-adolescent and suffering from acne “ . . what if she finde fault with these spindle shanks, or els with these blacke spottes upon your nose?”

Evidence such as this suggests that all the features of voice change, adolescence and puberty we know about today were both known about and exploited in earlier centuries.

It is just that the theorists of the time were unable to explain their observations. The scientifically influential Francis Bacon clearly understood there to be some association at puberty between a deeper voice and enlargement of the “spermaticall vessels”. He was at a loss to understand how this happened. An unwillingness to question theories based upon the humours held back possible progress.

The Cause of Changing the Voice, at the yeares of Puberty, is more obscure. It seemeth to be, for that when much of the Moisture of the Body, which did before irrigate the Parts, is drawne downe to the Spermaticall vessells; it leaveth the Body more hot than it was; whence commeth the dilatation of the Pipes (Bacon, 1646: 112).

The deeper voice resulted from a “dilation of the pipes” (i.e. broadening of the vocal tract) and this resulted from a presumably temporary excess of heat as the cooling fluids were drawn into the testicles. A relationship between growth of the testes and enlargement of vocal tract had long been known. References to castrati would suggest that much of this knowledge resulted from the discovery that the high voice was preserved by castration. Until Garcia developed his laryngoscope, however, the knowledge of the vocal folds we take for granted today proved elusive. Maffei’s 1592 treatise is possibly the most substantial piece of scientific writing on vocal pedagogy before the nineteenth century. He understood that sound is the vibration of air, and he understood the concept of frequency in comparing child and adult voice pitches.

But, when the contrary, the force of the anima advances and overcomes the air in such a way as to push and move it quickly, the voice must be produced high. From this can arise the cause why little boys and girls have little voices and high. Since the vocal cords being small, it is necessary for the air that is contained in them to be little, whence being moved swiftly by the power of the mind anima makes a voice high and small (Maffei, 1592, trans. Honea).

His frequent use of the term “vocal cords” is notable, but his understanding seems to be different from ours. Maffei appeared to believe that the vocal cords extended in length from throat to lung and seems to suggest that the cords were somehow an active part of the trachea. He had seemingly observed the structure of thyroid cartilage and attributed, not incorrectly, a defensive function to the tissues within it.

The top of the vocal cords is composed of three cartilages, of which the largest appears to us in the manner of a shield; it is that knot that is seen in the throat of every man. This has been made so hard for the defense of that place and is like a shield, so one calls it scudiform. In the interior of this there is contained another one, made for a greater defense, if perhaps the first is not enough, and this is without a name. Within this, namely in the middle of that place, there is another of them called cimbalare made in the likeness of the mouthpipe of a bagpipe, and in this is made the repercussion of the air and the voice (ibid).

It is not entirely clear what Maffie meant by “cimbalare”. It may be another word for glottis or it may imply a striking together. Either way, Maffie was heading in the right direction and what is of significance here is the fact that his interest does not seem to have been shared by later writers. There is a gap of some three hundred years before scientific progress is resumed. Revered Italian pedagogues who have influenced boys’ singing, such as Tosi (c. 1653 – 1732) or Mancini (1714-1800) were focussed almost entirely upon perceptual matters, somewhat driven by the rather subjective criterion of opinion. This is well reflected in the title of Tosi’s main work “Opinioni” translated as Observations on the Florid Song or Sentiments on the Ancient and Modern Singers. By “ancient” Tosi meant a timescale of less than fifty years which indicates his disapproval of trends within his own lifetime. The influence of the old Italian masters upon the way English boys sang declined over a similar period, and is addressed in the next chapter.

Writing in the eighteenth century, Mattheson does recognise the fundamental role of the “cleft of the glottis” as the “true cause of the tone”. John Butt has located a telling passage in the 1981 translation by Harries.

It is indubitably true that such an epilglotis contributes to the delicacy and tenderness of sound . . .It also contributes much, perhaps more than the uvula in the mouth….Thus the unique human glottis is the most sonorous, pleasant, perfect and accurate instrument (trans Harris 1981, cited in Butt, 1994: 85).

The uvula is of course more readily visible than the vocal folds, so it is entirely understandable that a role in the actual production of tone was assigned to it. The darker cavity beyond was identified but the role assigned to it, though fundamentally correct, may have been fortuitous speculation. Mattheson may also have recognised that voice change in boys lags behind that in girls, enlarged “ducts and canals” having a less good effect in adolescent boys than in girls. In his Der vollkommene Kapellmeister (The perfect Kapellmeister) of 1739 we read that:

With boys, the strongly increasing ardours and humours generally enlarge and distend all of the ducts and canals of the body. This does not have such a good effect as is manifest with the female sex about the same time. as is easily seen, the natural accretion and release of the ardours and humours, hence also the enlargement of the passages and ducts in the throat whence undeniably derives the lowering of pitches, is impeded in castrati by the early removal of those organs from which all of the fertile humours come, and indeed before the power of enlargement of this last appears (trans Harris 1981, cited in Butt, 1994: 84-85).

Still, though, he refers to “ardours and humours”. The voice scientists of our present era, whose methods are based upon extended observation and measurement, have only just begun to have impact upon centuries of empirical knowledge gained from noting what produced the most pleasing results from singers.

Frederick Bridge (1844-1924) described his methods at Westminster Abbey, typical of the 1890s, in these words:

No formal system of voice-training is in use. The boys enter at from 9 to 10-½, not older. A new boy is placed in the middle of the row of choristers, so as to excite his imitative faculty to the utmost (Bridge in Curwen, 1895).

As recently as 1976, Lionel Dakers could write as director of the RSCM that:

the best vocal sounds are those which are produced naturally and with ease. The worst usually come from those whose voices have been ‘trained’, often by someone concerned with theories and methods alone. Boys usually sing with such ease because they seldom think about technique…It was reported that Varley Roberts…one time organist of Magdalen College Oxford said that it was merely a question of opening the mouth and singing (Dakers, 1976).

These comments were written before the level of scientific attention that has begun to be paid to adolescent voices since Cooksey first published his findings in the Choral Journal (Cooksey, 1977a, b, c). They were written before the level of attention that is now paid to historic pitch since the work of scholars such as Andrew Johnstone and Magnus Williamson or the three instruments created by the Early English organ project were conceived.

The exclusion of adolescents

In discussing whether the now largely defunct (as far as living boys are concerned) mean part was sung by boys or men, Peter Phillips wrote:

The irony . . . is that the best modern choirs tend to employ women to sing these parts; indeed, the idea of boys singing the mean part in modern performances almost never happens, whichever pitch is chosen (Phillips, 2005, present author’s emphasis).

My reaction to this is to ask why not. Given their historic role, surprisingly little use is made of living boys in historically informed performances of sixteenth century music.

One possible reason for this is the traditional exclusion of adolescent boys whose voices are deemed to have “broken” from the kinds of choir that perform the music of dead composers.

Drawing on Irvine Cooper’s original work, I pointed out that, whist some may be weak towards the bottom of the range, most boys who identify as “trebles” could sing in the range F3 to C5. In other words, they could sing a cambiata part. We looked at the song May it Be in the range A3 – B4 as an example, pointing out that this is a comfortable range for boys “in first change”, to use Cooper’s words. Nearly all boys of eleven or twelve can sing in this range, but only those with chorister training can comfortably reach the treble G5. The logical conclusion of this must be that the more common singing voice for boys is not treble but mean, the situation that existed in the sixteenth century.

That lower pitches were the norm in historic times is well established. Our understanding of sixteenth century pitch has been transformed by the Early English Organ project (RCO, 2015). The lessons newly learned from the reconstructed Wetheringsett, Wingfield and St Teilo organs were neatly summarized by Andrew Johnstone:

To many of the church musicians for whom early Anglican works are now core repertory, the present revelations about the original pitch of those works will probably not be very welcome news. Transpositions of the Fellowes type are by now so familiar and firmly established that they have acquired a time-honoured authenticity of their own that will be difficult, and perhaps even undesirable, to shake off. To scholars, editors and authentically minded performers, however, the Early English Organ Project has made it abundantly clear that transposition by a minor 3rd does not represent early Anglican music as it was in the beginning (Johnstone 2003: 522).

Choral music has perhaps been slower than purely instrumental music to adopt lower pitches. Issues arise when it does, and none more so than the suggestion that the modern countertenor voice is an anachronism. As Andrew Parrott observes, the countertenor has come to be “widely seen as the very emblem of early vocal music” (Parrott, 2015a: 1). To suggest that countertenors be excluded from cathedral choirs, or indeed that the Blackadder theme song be re-recorded, is likely to be regarded as something beyond heresy. Nevertheless Parrott’s Falsetto Beliefs (Parrott, 2015b; 47 – 121) and Simon Ravens’ Supernatural Voice (Ravens, 2014) mount substantial and hard to refute arguments that historically informed performances require not falsetto countertenors but high modal tenors. One of the main reasons Edmund Fellowes created the tradition of raising the pitch of sixteenth century music is that the lower pitch was so difficult for the adult male falsetto voices of his time. Boys (and girls) living today must therefore sing sixteenth century music as much as a whole minor third higher than those alive at the time it was composed, effectively for the convenience of the alto part.

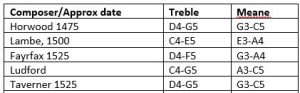

What if we were to pay the same amount of attention to boys’ voices as Parrott and Ravens have paid to adult falsetto voices? The mean voice may be the key. Roger Bowers proposed that mean parts could have been sung either by boys or men according to available resources (Bowers, 1988-1987), a carefully marshalled argument I once found convincing. Parrott has since fairly comprehensively demolished it and is confident that mean parts were invariably sung by boys. If this is indeed so, then consideration needs to be given to what kind of boys. Pre-reformation mean parts could range as low as E3, which is the bottom of today’s Cambiata II range. The mean part from Lambe’s Magnificat of 1500, to take one example, would not be effective if sung by an unchanged voice.

To hear this part as it might have been heard in the sixteenth century would require those adolescent voices too deep for any form of “treble” but still unable to reach the lowest tenor notes, with which readers should by now be familiar. Such voices have long been excluded from the types of choir that perform such works today, whether these are cathedral choirs or adult choirs specialising in early music. Perhaps then, the exclusion of adolescent voices is as much a barrier to historically informed performance as is the inclusion of countertenors. It is also the case that adolescent boys are being excluded from this type of music at the very time that their capacity for deeper understanding is taking off and their opinions and values are forming, so their absence from such potentially interesting performing and learning opportunities may be somewhat counterproductive to the long term health of serious or “classical” choral music.

The English Reformation

The imposition of a relatively austere, English rite in 1549 undoubtedly signalled the end of elaborate settings requiring two voices above the adult male polyphony, in publicly sanctioned worship at least. It was not just the high treble voice that disappeared when the two former boys’ parts were amalgamated into one. The lower medius voice suffered at least as much through being deprived of its range below middle C where mid-adolescent boys could have been particularly effective. The position is summarised by Parrott.

Given that during William Byrd’s tenure at Lincoln, puberty began at a similar age to today, but took longer to complete (see Chapter 4), almost any boy old enough to survive without his mother up to the age of fifteen or so could have sung in the C4 – D5 range and thus been a post-Reformation mean.

It is surprising how infrequently any of our established male choirs attempt performances of Byrd’s vernacular sacred music at pitches Byrd would have used. One exception has been the work of Bill Hunt of Fretwork with Bill (Grayston) Ives of Magdalen College. The historically informed performance of Byrd’s setting of Psalm 115 Teach Me O Lord the Way of Thy Statutes by the Magdalena Consort in association with Fretwork is pitched two semitones lower than the common F minor editions, meaning the highest voice need not ascend beyond today’s Db5. To my ears, the Magdalena Consort recording of this and of the Second Service sounds altogether more comfortable and convincing that the more commonly heard high pitch versions. Ives and the Magdalen College choir have performed other works in which their boys are effectively singing as means. Byrd’s O Lord Make the Servant Elizabeth is a good example. A notable feature is the clarity with which they can be heard on the phrase Give her her heart’s desire, which is at the bottom of the post-Reformation mean range. This is not always the case with living boys.

Byrd: O Lord, Make Thy Servant Elizabeth

Hunt’s use of viols may represent artistic license. Though such instruments were certainly in regular use for instructing the choirboys in music, their use as service accompaniment is harder to justify as an act of authenticity. On this occasion, I am going to rely upon Bowers who wrote:

I am aware of not a single convincing reference arising either from Byrd’s lifetime or from the years closely following it which indicates that viols were ever played in the course of the church service (Bowers in Turbet, 2012: 142).

I am less certain about the solo voice used. Though he had been a chorister up to the summer the recording was made, Stefan Roberts had developed an unmistakably countertenor quality that would be unlikely to have been heard when most boys progressed more slowly through puberty. It is understandable that an experienced boy would be used for an important recording, but I think it unlikely the sound Byrd heard has been captured.

For this, I turn to another recording made some years later by Romsey Abbey choir, to the accompaniment, not of viols, but of the St Teilo organ, the third and final instrument to be reconstructed under the auspices of the English Organ Project. Even if it were not used for actual accompaniment, a similar instrument would have set the pitch for Byrd’s choir.

The recording was the brainchild of the then director of music, George Richford. George had at the time an interesting idea that he should treat his girls as sopranos, recording a repertoire from the nineteenth century onwards, and his boys as means, recording a sixteenth century repertoire. I was able to undertake research with these boys during the period of recording and believe I may have been responsible for persuading George to use Andrew Johnstone’s new edition of Byrd Second Service, probably the most historically accurate now available. Notwithstanding Magnus Williamson’s recollections of a Westminster Abbey chorister’s boredom with the likes of the Tallis “Dorian” service (Williamson 2005), the Romsey boys seemed content enough with their vernacular English lot. George wrote of them:

Our boys are no different to other boys in other church choirs. They do not have physically lower voices and they are not on average older than similar choirs. But the post-1549 meane part, as epitomized by Byrd’s 2nd Service (in G minor edition by Andrew Johstone) is perfectly singable. On our disk we recorded this piece with 14 boys, 8 lower voices and the St Teilo Organ. It balanced well. It is my contention that range was sung by normal ‘treble’ boys but who did not sing outside of the meane range; not a countertenor, and not a changing boy’s voice. Some would describe this as not singing outside of ‘chest’ register.

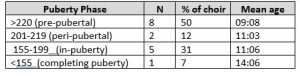

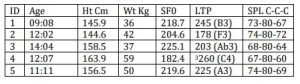

Access to data on the boys’ ages revealed the average age of all present on the day of the research visit to be 10:09. This is a relatively young choir, dominated by unchanged voices. The table shows the percentage of the boys reckoned to be at each of the four puberty phases by the criterion of SF0.

In Byrd’s day, it would be unlikely that a boy of fourteen would be completing puberty, though not impossible. Johnstone has the medius part range from C#4 – D5. Over half the choir could have accessed this in a child’s modal voice. The five boys who were in-puberty could also have accessed it with perhaps stronger tone in the lower range, though one or two might be troubled by looming laryngeal registration difficulty. Only the fourteen year old would be likely to be seriously challenged by the notorious “devils’ note” (see Chapter 5).

In Byrd’s day, it would be unlikely that a boy of fourteen would be completing puberty, though not impossible. Johnstone has the medius part range from C#4 – D5. Over half the choir could have accessed this in a child’s modal voice. The five boys who were in-puberty could also have accessed it with perhaps stronger tone in the lower range, though one or two might be troubled by looming laryngeal registration difficulty. Only the fourteen year old would be likely to be seriously challenged by the notorious “devils’ note” (see Chapter 5).

The boy chosen to sing the verse part was aged 11:10 at the time. He was subjected to a full vocal analysis. SF0 was higher than 220 Hz and no laryngeal breaks were detected in full-range glides. The verse as he promised to our forefathers ranges from D4 – C5 and to my ears, the lowest notes were weak, becoming all but inaudible behind the organ.

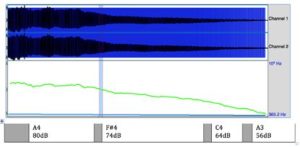

I undertook some further analysis. The figure below shows the SPL from C5 to the bottom of the boy’s range, taken from a downward glide.

C5 has been standardized to an 80dB reference level. A fall of 6dB represents a halving of sound pressure level (SPL) and this occurs around the note F#4. By the time C4 is reached, SPL is down to 64dB. The lowest clear note in the glide is A3, where the SPL has fallen to 56dB. Measured SPL is not the same as perceived volume, which is a psycho-acoustic property. 10dB is regarded as the psycho-acoustic point at which volume appears to have halved. Either way, the profile is not strong towards the bottom of the part.

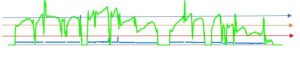

The next figure shows the SPL of the verse part. This is the dry voice without organ. The blue arrow represents the 80dB reference where the organ and voice would be well in balance. The orange arrow represents the point at which SPL has fallen by 6dB, and the red arrow represents the point at which the voice became all but inaudible through masking by the organ. This occurs on the final syllable of “ever”.

The actual CD and my experimental recording are similar. Both can both be heard here:

Experimental Recording

Actual Recording

How William Byrd would have reacted to this, or the kind of boy Byrd might have chosen, we cannot know. There are of course other considerations than my judgement that this might be an issue. The boy chosen would have to be sufficiently musical to sing a verse and mature enough to manage a professional recording session, almost certainly a consideration that would rate higher in a conductor’s set of practical priorities than the finer details of the acoustic profile of the voice. Nevertheless, given Cooksey’s acoustic profile of the midvoice I as having the “most desirable vocal color and power in the midrange area B4 – C5” (Cooksey, 1992: 56), I might have chosen a midvoice I had I been in a position to do so. For Byrd, that would likely have been one of his older boys, thus satisfying acoustic, musical and capability criteria.

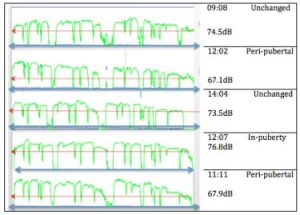

Troubled by this consideration as well as the countertenor quality of the Stefan Roberts recording, I designed an investigation involving five boys from Blackburn Cathedral. I had persuaded the then organist, Sam Hudson, that the proposal for a “quire pitch evensong” (without countertenors) that Andrew Johnstone and I had put together would be a good thing to attempt. I asked for five boys that Sam considered capable of the same verse part. The table below shows that they differed quite widely in age and physical maturity.

The far-right column shows the results of a vocalise in which each boy was asked to sing C4, C5 and C4 again in a continuous phrase. Gain was adjusted so that the C5 was sung at a reference level of 80dB. The left-hand number is the SPL of the first C4 and the right-hand number the second C4. It will be seen that in every case, less power is produced when the boy brings his voice down from the octave. A plausible explanation could be that there is more TA action in the first C4 than the second C4 (see Svec et al, 1999). This could be because these boys, trained as typical English cathedral choristers, sing with a TA-CT mix that tends to be dominated by CT action for most of their repertoire. When the pitch is suddenly reduced by an octave, CT remains dominant and the note is weaker.

Whether or not this explanation is correct, the boy whose C4 and C5 differ the least is number 2, a twelve-year-old probably in transition from midvoice I to midvoice II. The figure below shows the SPL for each of the five boys singing the verse part, dry voice under controlled conditions. The gain was adjusted at the post-production stage such that the highest was 80dB in all cases. The quantity shown in dB for each boy is the SPL reached at “ever” on Cb4. The closer this figure is to 80, the more consistent is the boy’s tone toward the bottom of the range.

It is important to stress that what is shown is consistency of tone across the range, not absolute power. Absolute power can, in a modern performance, be managed by adjustments in the organ volume or where the boy stands. Sixteenth century organs, however, did not have subtle, quiet stops enclosed in swell boxes, so it is possible that boys regularly produced more power in their TA dominated range than they do now. Ultimately dynamic balance might be controllable only by the act of choosing the singer. Drawing on what was learned at Romsey, sounds below the red arrow risk being weak, possible masked by the organ.

By this criterion alone, the boy chosen would be no. 4, who also gave a secure audition with no significant errors. No. 4 had the advantage of being one of the older boys, being aged 12:07 and in Y8. However, height, weight and SF0 indicate a boy well into the in-puberty phase. C4 was recorded as the bottom of his secure range. Below this, a laryngeal break was beginning to threaten. It is unlikely that Byrd would have experienced similar issues with a twelve-year-old. This makes an interesting contrast with No. 3, the oldest of the five, aged 14:04 but with weight, SF0 and LTP (lowest terminal pitch) characteristic of a voice that has barely begun to change. Apart from an unfortunate breath in the wrong place (which could easily be remedied by a second go) he would have been my first choice. He is, in other words, arguably the “right kind of boy” and his relative physical immaturity at age 14 makes him a prized asset in an age where boys progress quickly through puberty! No. 1, the youngest, also had promise as a potential “Byrd boy” and the advantage of more of his career ahead of him. All the samples can be heard here. The organ registration attempts to replicate the relatively uncontrollable stridency of a sixteenth century instrument.

09:08 Unchanged

12:02 Peripubertal

14:04 Unchanged

12:07 In puberty

11:11 Peripubertal

These observations are not offered as a definitive guide but as an invitation to consider what might be involved in selecting living boys as performers who might approximate boys alive at the time of the composer. There may be a “wrong kind of boy” in much the way that protagonists for viol consorts might argue that a modern violin is the wrong kind of instrument.

Before the Reformation

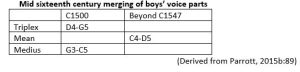

When we put the clock back to before the Reformation, however, we encounter a somewhat different situation. We now need to populate parts with two distinct kinds of boy. The table below, derived from Ravens’ work, shows some typical medius and treble pitch ranges.

The treble parts are the less problematic. Most commonly terminating on G5 and never ranging below C4 at today’s pitches, they are ideally suited to many of the boys we call “treble” today. Unchanged voices could sing them, as could midvoice Is much in the way boys do today. It would be some three centuries before people began to speak of “boy sopranos”.

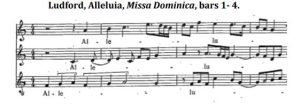

Missa Dominica

Nicholas Ludford (C1485 – 1557) held a post at what is now Westminster Palace but was, during the sixteenth century, St Stephen’s. According to Roger Bowers, he enjoyed the resource of seven boys and eighteen men. Ludford’s is one of the cases Bowers draws upon to support his theory of how either boys or men would have sung the meane part according to circumstance and available resource. It is in an account of Ludford that Bowers makes his assertion that boys’ training and ability to render either alto or treble part was ubiquitous. Ludford wrote two types of mass. The large festal masses were sung in the main church, but a daily Lady mass was sung in the crypt without the men. If Bowers is correct, a wholly authentic performance for the Lady mass would have seven boys, each of whom could sing either part as directed, and one adult male voice, the boys’ master.

Two commercial recordings of the following passage that I analysed present us with something of a dilemma.

One was by by the well-known and highly regarded Trinity Boys Choir and the other, transposed down a fifth, by Ensemble Scandicus, an adult group employing countertenors on the treble part and a deep bass. It was noted that, for the adult group, all three entries could be heard distinctively, and the parts were in perfect balance at the very start. The boys’ version, however, seems to suffer from a similar problem to the Byrd Magnificat. The mean entry on C4 is hard to hear and the parts are not clearly balanced until the boys singing mean reach a stronger point in their register. The full polyphonic effect is thus not realised in the boys’ version in the way it is in the adult version.

To pursue this matter further, I created a digital simulation with the East West Symphonic Choir software in which the mean entry is perfectly clear and distinct. It was not possible to dis-aggregate the commercial recording to individual parts. However, a second digital version was produced with the sound level of the mean part reduced to match that of the Trinity boys’ version on the entry note of C4. The necessary reduction in level was found to be 10dB, i.e. a reduction to half the perceived volume. At this level, the balance was poor for the whole four bars. Finally, a manipulated version of the digital mean part was created to replicate the acoustic profile of the boy who sang the verse part in the Magnificat. The result was indeed similar to the original Trinity version.

Trinity Boys Choir

Ensemble Scandicus

Digital Version

Digital Version with matching acoustic profile

There are perhaps two issues here. Ludford’s polyphony is accurately and musically reproduced by an adult group, but this cannot be considered an historically authentic performance since the pitch is far from the original and the vocal resources clearly very different. The boys’ version may come closer, but questions about whether the “right kind of boys” were used need to be answered. I have heard it said that English boys are characteristically weak in the A3 – E4 portion of their voice and have certainly witnessed more robust tone in German boys. However, to the best of my knowledge this has not been properly researched and I have not had the opportunity to do so. We are thus left with some open questions about training methods and about Bowers’ assertion that all of Ludford’s boys could equally well have been “alto or treble”.

Missa Sine Nomine

John Taverner’s Missa Sine Nomine, also known as the “mean mass” is an unusual work and certainly one that merits an interest boys’ participation in historically informed performance. Its date of composition has proved frustratingly elusive, but the stylistic evidence points to it being a relatively late work, possibly not that long before Taverner’s death in 1545. This was a time when Taverner was composing occasionally in retirement, having the luxury of freedom from the obligations of musical employment and occupying a position in civic life. Sandon (2014) describes Missa Sine Nomine as the most thoroughly imitative of all Taverner’s works, exhibiting many of the stylistic features of mainland European compositions. It is in five parts, scored in the Peterhouse Caroline part books for meane, three tenors and bass. The omission of treble is therefore remarkable. As a late work, though, it would have been written well after Taverner’s period in Oxford and the Cardinal College forces of some sixteen boys would no longer have been available.

A key piece of evidence is a note in the composer’s own hand reading “finis quod taverner for iiij men and a childe”. A similar note appears for Taverner’s In Pace in the Gyffard partbooks “for iij men and a childe” where “childe” again refers to meane. Is the singular of “childe” intentional? Sandon believes so. Taking account of the small resources and the stylistic evidence of a late date of composition, it is likely that the work was written in Taverner’s late Boston period when even the St Botolph’s choir may have been disbanded. The “childe” that Taverner may have written for therefore becomes a very interesting person in music history! Despite this, there are to my knowledge no recordings of the work where the mean part is performed by a “childe”. Two recordings could be traced, one by Pro Cantione Antiqua under Bruno Turner and the other by the Chapel Musick under Philip Cave. Though scholarly editions, both ignore the composer’s direction and employ countertenors instead. The digitally created version below is perhaps the only recording in which boys’ voices sing the meane part and no countertenors are used.

Taverner: Sanctus from Meane Mass

The meane part is pitched between C4 and C5 and, unlike the other parts, never exceeds an octave in range. Comparison might be drawn with some of Taverner’s earlier masses, where he was writing for both treble and meane. The meane part of the Gloria Tibi Trinitas has a similar tessitura to that of the meane mass. A boy who could sing the meane mass could perfectly well sing the meane part of the Gloria Tibi Trinitas. There is no descent to the low range of the Lambe Magnificat that would be impossible for an unchanged boy voice. The “childe” could thus be a similar one to the boy chosen for Romsey’s recording of the Byrd, though he would clearly need to be a mature and competent one to sustain the task of recording as the only boy in an otherwise adult group. Again, “Boy 3” from Blackburn might be a good choice. Aged 14, he would be suitably mature and experienced whilst possessing none of the countertenor timbre which it is surely necessary to avoid if we are to hear what Taverner probably heard. Almost certainly, a performance involving a “childe”, however proficient, would be less secure and accomplished than one involving a professional countertenor, but might that not be what is required if the highest levels of authenticity are sought?

How high is high?

The sustained, improbably high tessitura demanded by David Wulstan is losing popularity but influential choirs such as The Sixteen seem to persist with it. There are, for example, two recent recordings of Mundi’s In Medio Chori Magnificat. One is by York Minster Choir and is sung at the pitch adopted by the Timothy Symons edition (Cantus Firmus). The other, by the Sixteen is sung a tone higher. That the pitch chosen by Christophers is uncomfortable, even for today’s highly trained boy choristers, ought to alert us to a possible error. The irony is that Wulstan believed he was being objective when he stated that:

In church music of the early seventeenth century, found in ‘cathedral’ type part books, no problem exists, for two reasons: first, the part books are what we might call eponymous, and secondly, the music is at church, i.e. organ pitch, which is a known factor (Wulstan, 1966/67: 97).

This was written in 1967, long before the Early English Organ project. We have to be very careful when we claim that we “know” something, particularly when the evidence is as fragmentary as is common in early music sources. It is, in retrospect, extraordinary that Wulstan and other similarly minded individuals never thought to base their observations on the many living boys potentially available for study. The evidence for what is a sustainable, comfortable range for a boy’s voice, is there for all to see.

Parrott’s view is this:

. . .the treble, revived occasionally during the early decades of the 17th century, called for ‘a high cleere sweete voice’, but the ‘very high treble’ seems to be a 20th-century invention, evidently born of the high-pitch hypothesis and of a modern appetite for ‘extra and desirable brilliance’ (Parrott, 2015: 20).

Modern high pitch choirs have their following and do have seem to have created a certain appetite for extra brilliance. The one thing they do not have is boys amongst their membership. As far as choral music of the fifteenth, sixteenth and seventeenth centuries is concerned, G5 is “high”. It is a tone higher than than the average range of A3 – F5 given by Cooksey, so represents the difference between the highly trained boy who can truly claim to be a “treble” and more average boys who are better classified as means, particularly once C5 becomes the top of their range on becoming midvoice I (see Chapter 5).

Weelkes’ Fourth Evening Service

One of the happiest marriages of recent times has been between the choir of Durham Cathedral and the Wetheringsett organ. This has resulted in an historically informed recording of an unusual work that has long fascinated me. Somewhat misleadingly titled incorrectly the “Trebles Service”, Thomas Weelkes’s fourth evening service is unique in having verse parts for two means. Peter Le Huray’s 1963 edition of the work reconstructed a treble part from the top line of an organ part (several copies exist, and he did not state which he had used). That there ever was a treble part is uncertain for no complete treble part books have yet been found. Le Huray’s argument that the part must nevertheless have existed as the harmonic texture is uncharacteristically bare without it is borne out by examination of the score (LeHuray, 1967: 309).

The Fourth Service was in the regular Rochester repertoire under Robert Ashfield during the 1970s and I would enjoy listening to various boys’ attempts at the verse as I sat in the congregation as a young student. Rochester always omitted the high part in those days and I was none the wiser until I discovered Wulstan. By this time, I was directing a choir of students and lay clerks called the Canterbury Renaissance Consort. With the zeal that only a young man in his twenties can have, I set out to remedy Rochester’s “failings” as soon as possible with a high pitch performance including the infamous “brilliant” treble part (It may have been in Worcester Cathedral and one of the soloists was my late first wife. I still have the recording).

I shall never know whether Ashfield omitted the high part for scholarly or purely practical reasons. I suspect the latter, but that is of no little significance. He must have thought it too high for his boys. He did not, in the 1970s, have at his disposal the scholarly editions of recent years, still less the reconstructed instruments of the Early English organ project. In mature years, I have come regret my earlier misguided flirtation with Wulstan. A 1996 recording by Winchester Cathedral choir under David Hill had the A5 of Le Huray’s edition as a G5, but the Durham recording has its pitch set a further 43 cents below this by the Wetheringsett organ. Though both performances are of high quality, the Winchester boys are “helped” by the quiet gedackt stop whereas the Durham boys are singing under conditions closer to the original.

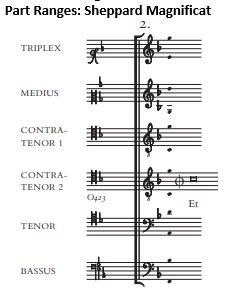

The solution to all the difficulties of impossibly high (for boys) pitch is disarmingly simple. If the pitch is brought down so that it is in the most comfortable range for means, then it also falls neatly into the readily attainable range for trebles. Nowhere is this more clearly seen than in Magnus Williamson’s recent scholarly edition of Sheppard’s six part Magnificat.

The closeness of the correspondence between the triplex and medius ranges here and the ranges found in the many boys I have tested over the years (to say nothing of Cooksey’s work) makes a very convincing case. Moreover, the two contra-tenor ranges confirm that there should be no need for falsettists, whilst the tenor ranges matches more closely the ubiquitous baritone of today. The need (aside from some capable boys) is for more adult singers to venture beyond the comfort zone of the baritone range they had as adolescents, either to develop as appropriate a full bass voice or the kind of high tenor needed for music of this period. The point might be made to those living boys who sing in choirs without even knowing that they might be either a treble or a mean (there are many). For the adventurous cathedral, there might even be the possibility of a pre-Reformation evensong in which the countertenors are replaced by the boys who left the choir the year previously!