A new science

Notwithstanding my remonstrances, the Dean and Chapter decided yesterday to uphold the doctor. I tried his voice last week, and he sang with full, rich tone up to the C above the stave, and that after he had been skating from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. I should have thought that a boy who could skate all day could not be in such a ‘feeble’ state as represented by the medical man. Three months ago a boy with a beautiful voice was sent away for the same reason. So you see what uphill work it is for me” (unnamed cathedral organist in Curwen, 1891).

Introduction

I am calling the period 1850 – 1950 the “early scientific age”. The late nineteenth century was a time that witnessed an unprecedented blossoming of technology and science. Darwin’s Origin of Species had been published in 1859. The Bessemer process for modern steel production was patented in 1886. Medicine, voice science and vocal pedagogy enjoyed similar advances. Edward Stubbs’ Practical Hints on the Training of Choir Boys is dated 1888 and John Curwen’s the Boy’s Voice 1891. Francis Howard’s The Child-Voice in Singing treated from a physiological and a practical standpoint and especially adapted to schools and boy choirs was published 1895 and is a remarkably advanced scientific work. Behnke and Browne’s The Child Voice, Its treatment with regard to after development (dedicated to John Stainer) in the previous decade is a similarly remarkable work, but for different reasons. It contains a thoroughly comprehensive survey of the views of people considered expert or knowledgeable at the time.

These were all substantial works and the like of them has not been seen since, a point made by Skelton (2007) who referred to a “serious gap in physiologic knowledge that is vital to understanding vocal development in young voices, specifically the period preceding puberty” (my emphasis). Skelton’s suggestion that there has yet to be a review of the issue comparable in scope to that carried out by Behnke and Browne in 1885 is well founded (Skelton, 2007: 538).

Though they achieved much, researchers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century were impeded by their inability to access the inside of a working larynx. The laryngeal mirror, for all the advances it brought about, was a crude instrument, clumsily invasive and disruptive of singing technique. It was all but impossible to use it on children who, even if they could tolerate it, would surely not behave in their normal carefree way for singing. Voice science has only begun to come of age since electronic and digital instrumentation has become readily available and I have already covered that in some depth.

From “opinioni” to hypotheses

We saw in the previous chapter that vocal pedagogy in centuries before the nineteenth was almost all empirical. The old Italian Masters based their work on their experience of how beautiful tone was produced and they supported their assertions by strongly expressed opinions. The scientists of the time made many observations but were unable to account for much of what they saw, being wedded to ancient medical beliefs that had evolved relatively little. The methods of the late nineteenth century represented a considerable advance but were still not based upon the rigorous approach to measurement we take for granted today. In some ways, they were a half-way between the old “opinioni” and a more objective methodology. A common approach, used to particular effect by Curwen and by Behnke and Brown was to interview a wide range of expert practitioners. It is worth quoting fully from Benkhe and Browne’s preface:

The chief need seems to be the collection of facts well observed by many persons. I say by many, not only because many facts are wanted, but because in all difficult research it is well that each apparent fact should be observed by many; for things are not what they may appear to each one’s mind. In that which each man believes that he observes, there is something of himself, and for certainty even on matters of fact, we often need the agreement of many minds, that the personal element of each may be counteracted (Behnke and Browne, 1885: 7).

The recognition of individual subjectivity represents a major advance, but we now know just how many scientific phenomena are counterintuitive and unlikely to be observed by the majority for precisely that reason. It would take until 1934 for current standards of falsification to be proposed by Karl Popper. Living before the acceptance of Popper’s views, observers of the late nineteenth century were constrained by the conditioning of their musical and social worlds. They lived through the period known as the choral revival of the Anglican church, a time of immense upheaval and rediscovery of the boy voice. To understand the significance of this, we first need some appreciation of why a revival was necessary. A difficulty that confronts anybody wishing to document the development of boys’ voices between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries in England is the paucity of information. Documentary sources from which reliable information about how boys sang are hard to come by, largely because boys either did not sing at all or sang very badly.

Rainbow (1967) describes the situation in parish churches as one of gross irreverence resulting from over a century of puritan laxity and decadence. Large three decker pulpits obscured views of the alter and sanctuary, which was just as well since the latter was used for storage and the former for seating during the lengthy sermons. He relates the following incident as typical:

One parish clerk, we learn, sang the services with a quid of tobacco wedged in his cheek, punctuating his liturgical utterances by spitting from the lower deck of

the pulpit after each Amen (Rainbow, 1967a: 8).

Boys did survive in at least some cathedrals, whether they sang much or achieved any kind of standard is doubtful. According to Mould, the historians of Bristol Cathedral School and the Prebendal School Chichester have been unable to find a single piece of evidence about their eighteenth century choristers (Mould, 2007: 145). As for St George’s Windsor, the source of some of the best and most complete records of sixteenth century boys, there commences from 1732 “a lengthy silence on the singing-boys’ affairs”. The researcher of boys’ singing techniques will find virtually nothing and is left to ponder on the meaning of “loud and violent choral singing . . . filled with screaming from the most wretched voices” (Jerold, 2006: 79).

The impact of the Oxford Movement and reformers such as Maria Hackett I have discussed in an earlier volume (Ashley, 2009). Rainbow (1967b) expounds at length on how the introduction of universal elementary education which included instruction in singing was also significant. It was the combination of all these things that led to the unprecedented outpouring of substantial texts on children’s voices, boys receiving the lion’s share of attention since the new-found enthusiasm for the ancient roots of the Anglican church resulted in a renewed enthusiasm for the exclusion of women and girls.

Avoiding the “chest voice”

It is possible that the nineteenth century writers over-reacted against the “screaming of wretched voices” for to a letter they were united in their condemnation of the “chest voice”. Francis Howard was writing principally for those who were to teach in the elementary schools.

The primary end, then, of the author has been to show a scientific basis for the use of what is herein called the head-voice of the child, and to adduce, from a study of the anatomy and physiology of the larynx and vocal organs, safe principles for the guidance of those who teach children to sing (Howard, 1895: preface to the second edition, p7).

His explanation of laryngeal registration did not differ in any great way from that which we accept today. If there is any inadequacy, it is with the assumption that what has been discovered about adult voices applies equally to immature voices. Such an inadequacy persists to the present day, so Howard and other writers of the same persuasion can hardly be censured. The desire to avoid the ugly tone in the “speech register” that we hear so often today from primary school children (boys and girls equally) may account for the total prohibition of the “chest voice” rather than the more moderate advice we might give today that the whole voice should be used carefully once access to the CT dominant part of the range has become habitual. Cooksey’s observation that “breaks/shifts caused by inappropriate application of heavy mechanism in lower register” remains valid (Cooksey, 1992: 55, my emphasis).

Of no little significance is Howard’s recognition that “a physiological basis has reinforced the empirical deductions of the old Italian school”. He states his safe principles thus:

We may then conclude from the foregoing that children up to the age of puberty, at least in class or chorus singing, should use the thin or head-register only.

1st. It is from a physiological standpoint entirely safe. The use of this register will not strain or overwork the delicate vocal organs of childhood.

2d. Its tones are musical, pure and sweet, and their use promotes the growth of musical sensibility and an appreciation of beauty in tone.

3d. The use of the thick or chest-voice in class-singing is dangerous. It is wellnigh impossible to confine it within proper limits (ibid: 32).

His account of the voice at puberty, though written in 1895, is more detailed and accurate than many of the books on children’s singing written in our own time. Of particular interest is his insistence that if the unchanged voice has been trained in “thin register” only, the boy’s voice will be at its best between the age of twelve and its “demolition at puberty”.

From the time children pass the age of twelve years on to the period of puberty, the child-voice is at its best, and if the use of the thin register has been faithfully adhered to in the lower grades, the singing-tone will now be both pure and brilliant. It will be found not at all difficult to carry the same voice as low or lower than middle C without any perceptible change in tone-quality (ibid. 79).

His use of the term “demolition at puberty” belies the claim that is sometimes made that boys can safely sing soprano for a period after puberty, though we have seen in earlier chapters that some of the living boys studied have done this through switching their production for a while from M1 (“thick register”) to their newly acquired M2 (“thin register”). A longstanding difficulty here is the assumption that such discrete “thick” and “thin” registers exist in the unchanged voice. We have seen that unchanged voices do not experience a laryngeal break. They are modal throughout their range. This is still an area of confusion. There is, of course a “head” end to a good modal voice when CT action is dominant and a “chest” end when TA action is dominant. The objectionable voice of the primary school child that is called “chest” probably does result from a lack of CT action. However, it is sometimes implied that English choirboys of the early twentieth century sang in one register only. Kenneth Phillips has been critical of what he calls the “English choirboy”. He wrote in 2013 that:

English choirboys sing only one vocal part – treble. Because most of them are not permitted to use even a mixture of chest and head voice, the head-voice sound is extended below pitch C4 as low as possible (Phillips, 2013:93).

I have always wondered how he came by the idea that English boys are “not permitted” to mix chest and head voice. He seems to think the Royal School of Church Music (RSCM) responsible, but in 1927, its director Sir Sydney Nicholson wrote:

One great difficulty for a boy when first he acquires the use of the head-voice is to blend it with the tone of the lower register. This can be best secured by the practice of scale passages downwards, starting from a note well within the head-voice, such as F 5th line or G first space above, and carrying down the same production to about A second space, and then changing into the chest voice. As soon as the habit of singing the upper notes in the head-voice has been definitely acquired, the practice of scales in both directions should be undertaken; it is surprising how soon the two registers will become blended (Nicholson, 1927).

A few years later, Edward Bairstow wrote the following for the RSCM:

Treble C is the middle note of most boys’ voices. All voice training should begin from the middle. Common sense tells us that to allow a beginner to commence with the extreme of anything is ridiculous. The old idea of starting boys with head notes was silly and unnatural. A boy has a middle voice like a woman, not head and chest notes only. His chest notes are rarely used (Bairstow, undated: 7).

If treble C is literally the middle of a typical boy’s voice, he will have a range of two and a half octaves from A3 to E6, i.e. four semitones above soprano high C. David Wulstan would be a happy man. Perhaps a little more scientific measurement and a little less opinioni might not come amiss?

Boy altos

English boys today rarely sing alto because the countertenor voice is preferred. It has not always been so for the simple reason that the countertenor voice as we recognise it today did not exist before Alfred Deller. Prior to the choral revival, the alto part itself was often absent. It is clear from primary source material that the reign of Queen Victoria in England was characterized by growing concern that the alto line, which had become neglected and a poor relation of other parts, should be brought in line. There was evidently more than a little angst concerning how it should be populated in order to achieve this. Conductors apparently faced a dilemma of choosing between two equally unsatisfactory alternatives – male falsettists with “voices like calliopes” (steam whistles tuned to musical notes) or boys singing in “raucous chest tones” (Stubbs, 1897). This dilemma was forced upon them by a refusal to countenance an obvious alternative that had proved more than satisfactory in mainland Europe – the female contralto.

On this score, England was if anything moving backwards as a result of what we might today view as a romanticised obsession with the early church. Ravens contends that female voices would have been unthinkable in nineteenth century England, an attitude he puts down to the tendency of the Anglican church to have seen itself as an “adapted Catholic one” rather than a “radical protestant one” (Ravens, 2014: 173). Nevertheless, as standards rose under the influence of the Oxford movement “anybody or nobody” on the alto part ceased to be acceptable. Pressure came from mixed choirs in mainland Europe where the female altos could readily sing in unison with sopranos when composers called for it. Ravens provides a striking illustration when he compares Wesley’s Ascribe Unto the Lord (1853) with Mendelssohn’s Hear My Prayer (1844). In the former, the altos sing in unison with the tenors and basses in the range B2-E4 whilst in the latter the altos are expected to sing in unison at the same pitch as the sopranos, range D4- D#5 (Ravens, 2014:174-175).

John Curwen’s The Boy’s Voice (Curwen, 1891) is a veritable tour de force survey of contemporary practice and opinion with regard to this. Curwen himself accepted that men “generally with bass voices singing in their ‘thin’ register” had, until this time sufficed as altos:

For this voice our composers of the English cathedral school wrote, carrying the part much lower than they would have done if they had been writing for women or boy-singers (Curwen 1891: 78).

He did not, however, see this as a situation that could continue, since growing eclecticism resulted in “singing music from oratorios, cantatas, and masses that was composed for women altos, and is far too high in compass for men” (ibid.) Curwen then devotes an entire chapter to the boy alto, taking a somewhat optimistic tone.

There is no doubt, moreover, that the trouble of voice-management in boy altos can be conquered by watchfulness and care. At the present time there are, as the information I have collected shows, a number of very good cathedral and church choirs in which the alto part is being sustained by boys (Curwen 1891:XIII, 1).

Again, it is the problem of “modern” music (i.e. Mendelssohn) that is the issue. One of Curwen’s many respondents confidently recommended “carefully trained” boy altos as the solution. Whilst retaining “two men altos”, James Taylor, then organist of New College Oxford, reported finding boy altos “very effective in modern church music, such as Mendelssohn’s anthems, &c., where the alto part is written much higher than is the case in the old cathedral music.” (Curwen, 1891: 79). Another of Curwen’s respondents (Mr Thomas Ely of St John’s Leatherhead) was impressed by the boy altos he had been able to train, though made a pertinent observation with regard to the Ascribe unto the Lord problem:

I may say that in my choir at this College I have four or five very good boy altos. One is exceptionally good, possessing a natural alto voice of remarkable richness and beauty. In our services and anthems he takes the solo alto parts, and in my opinion he is far superior to a man alto, except in such anthems as Wesley’s ‘Ascribe unto the Lord’ (expressly written for choirs possessing men altos), in which he cannot take some of the lower notes. The compass of his voice is from F to E♭.”

Francis Howard was not convinced, calling the boy alto voice an “unmanageable and unmusical” one, “harsh, unsympathetic, hard to keep in tune.” He regarded its presence in the choir as a “constant menace to the soprano tone”. He clearly viewed it as a self-inflicted musical wound consequent upon the refusal to employ women altos (Howard 1895: 127). Stubbs was also at a loss as to what to do if women were to be prohibited. Neither of the two male alternatives was satisfactory, yet the “coarse bray” of boys was tolerated on account of an apparent prejudice at the time against adult males on the alto line:

Thus the shrill piping of the average counter-tenor, as heard in most of our choirs, is supposed to be the real thing, and it is almost impossible to alter this judgment. Here the parallel ends, for even among musical persons who know good from bad, the boys’ coarse bray is apt to be overlooked, while the cutting tone of the ill-trained counter-tenor is condemned off-hand, without appeal (Stubbs 1908: 8).

Sydney Nicholson, who we have already met as founder of the RSCM and advocate of a blended production in the boy voice, also regarded boys as unsatisfactory on the alto line. Somewhat ahead of his time though, he foresaw and recommended in 1927 the situation we now have – female altos even in choirs that are otherwise still all male.

With regard to the alto part the case is somewhat different. It is often difficult to secure good men altos; boy altos need more training than can ordinarily be given them, and even at the best are not very satisfactory. But a good solution is often to be found in the employment of women for the alto part: if the voices chosen are not of the heavy contralto type, but are more in the nature of mezzo-soprano, a good blend can be secured that is very effective for chorus work (Nicholson, 1927).

“Heavy contralto” is an interesting term. The fourth (1940) edition of Grove’s Dictionary attributes the claim that boys are “not very satisfactory” to simple neglect of their potential. With regard to this, a German boy in an elite choir of today might sing for 18.5 hours a week but only 1.5 hours of this might be spent in performance. An equivalent English boy might sing for 16.6 hours per week, but 4.5 hours will be performance with only 12 hours rehearsal (Williams, 2010). There is indeed less time for the English choir director to manage two sets of boys, one of which must be capable of reading largely at sight an inner part. Undeterred, Grove’s makes the claim that the neglected voice of the “true boy contralto” is one of the “most beautiful in existence”.

The peculiar form of voice now called the counter-tenor: an unnatural register which still holds its grounds in English cathedrals, with a pertinacity which leads to the lamentable neglect, if not the absolute exclusion, of one of the most beautiful voices in existence – the true boy contralto (Colles, 1940: vol. 4, 334).

Use of the term “contralto” here implies a ready supply of boys able to phonate a resonant F3. Andrew Parrot asks a rhetorical question that suggests that much of what was learned about boy altos during the nineteenth century may have been forgotten:

Today’s Anglican choirboys are almost invariably required to sing as trebles, yet it is undeniable that plenty of boys more naturally sing in a lower range. (Are all female singers sopranos?) (Parrott, 2015: 19).

It would be interesting to know where Parrott’s belief that it is “undeniable” that plenty of boys more naturally sing in a lower range comes from. A notable writer on the topic during the 1930s was William “Father” Finn (b1881). His two volume Art of the Choral Conductor was first published in 1939. According to Finn, “there is no such thing as the true boy alto” (Finn, 1939: 126). A 1977 thesis on the boy alto (Larson, 1977) cited this and two other similar references. Richardson (1914) was of the opinion there may be such a thing as a natural boy alto, but that is very scarce. Duncan McKenzie, a precursor of John Cooksey, believed that such a type of voice is “rare” (McKenzie, 1956).

On this score English and German practice differs significantly. German boys today can be classified as alto or soprano between the ages of 7 and 10, whenever they are first “ready to practise polyphonic singing” (Gierszal, 2015; Hahn, 2004). It is according to what we know about genetic variation in pitch, highly unlikely that any of that age, other than an exceptional few, will have voices of contralto quality down to F3. It is more the case that the relatively pliable young voice can be conditioned to perform towards the top or bottom of a potentially quite large range without necessarily reaching the extremity of an adult soprano or contralto. One of the most remarkable German boy altos of recent times has been Panito Iconomou, singing under Nikolaus Harnoncourt. The extract below, though it sounds powerfully “alto”, has a tessitura of Db4 to Db5 and descends no lower than Bb4.

Panito Iconomou

Larson’s findings here need to be taken seriously, not least because they are supported by John Cooksey’s later work (Cooksey, 1977; 2000), which has yet to be seriously challenged in scientific research. According to Cooksey, A3 is the bottom of the range for the majority of boys. Whilst boys able to phonate clearly the G3 are sometimes encountered, an F3 would certainly be a rarity amongst unchanged voices. McKenzie conducted much work in the field of changing voices and would have been well able to distinguish between a naturally low unchanged voice and a changing voice. McKenzie and Cooksey are both supported on this important point by a leading researcher of today, Ingo Titze. Titze has shown that prior to puberty, in spite of considerable growth in height, boys’ voices remain relatively on a pitch plateau. Although there is some genetic pitch variation it is not of the magnitude found in adult female populations (Titze, 1992; 1994).

Howard had much to say about this greater pliability of the child voice in his 1895 treatise (pp 30–34). Curwen was apparently impressed in 1899 to find that James Bates of the London Chorister School did not recognize alto (in a boy) as a separate voice “All his boys are capable of the full range” (Curwen, 1899, cited in Beet, 2001). The question at issue, of course, is that of defining “full range”.

Behnke and Brown take a somewhat different and somewhat interesting line, seeming to think that alto rather than treble is the norm for boys. Perhaps there is an association here with the proposition that the mean is the normal, or certainly more common, voice for boys (see Chapters 8 and 9). They state that it “may be accepted as a fact that the majority of boys have alto voices, the majority of girls, soprano” (Behnke and Brown, 1885: 11). Later in their text, they offer the following testament from Dr Parry:

In Wales boys never did sing treble, always alto without exception. In church choirs a few may have done so; but in Wales the population are chapel-goers, and their choirs are as stated (ibid, p41).

Clarity is needed as to whether what is being referred to is an unchanged boy child’s voice or the voice of an adolescent, perhaps formerly soprano or “treble”, whose voice has begun to change. Whether or not a voice that is in most cases short-term and transitional can be considered a true voice is a moot point. It is evident from an analysis of all the responses in Curwen that what is being referred to is actually in many cases the adolescent voice. Dr Bates of Norwich Cathedral furnished Curwen with a detailed analysis of boys’ vocal ranges together with the locations of their register shifts. The following clearly confirms that Bates understood the lower voice to be a consequence of puberty, not natural genetic variation:

No fixed compass can possibly be given to the different registers, as the older a boy becomes the lower the change occurs; the head register often being used as low down as A (Curwen 1891: 63).

It appears that at Norwich, voice change was being well-managed. This was clearly not always the case. Precentor Dickson of Ely Cathedral opined that:

the coarseness (at any rate) of boy-altos in English choirs is due to mismanagement by the choirmaster. His usual plan is to turn over to the alto part boys who are losing their upper notes by the natural failure of their soprano voices. This saves trouble, for such boys probably read music well enough, and they are simply told to ‘sing alto,’ and are left to do so without further training, until they can croak out no more ugly noises (ibid: 61).

In adolescent voices, downward extension of the former range could be quite effective in the alto range. One other quotation from Curwen is well merited. George Garrett of St John’s College Cambridge provided a lengthy response that included this:

As regards the break question, the advantage, in my experience, is wholly on the boys’ side. A well-trained boy will sing such a solo as ‘O thou that tellest,’ or such a passage as the following without letting his break be felt at all:

This passage, which is from the anthem, ‘Hear my crying,’ by Weldon, I have heard sung by an adult alto, who broke badly between E flat and F. The effect was funny beyond description (ibid: 59).

Howard held a clear view that a good English boy alto was a former boy soprano who had been taught to use mainly his “head” register and to continue to use this register as his voice began to change.

Boy sopranos are plentiful, basses and tenors are easily obtained, but good male altos, men, not boys, are almost unknown outside of a few large cities. This state of affairs has led, in many cases, to the employment of boys as altos, and they have of course sung with the thick or chest voice . . . There is a recourse, however, and it is at the command of every choir trainer whose sopranos have been taught to sing with the head voice alone. It is to select certain sopranos, and when the voice breaks, let them pass to the alto part, and continue to use the head voice (Howard, 1895:128, emphasis in original).

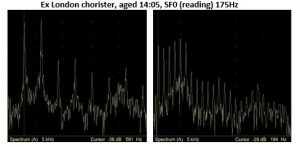

That such voices can exist today was demonstrated during a visit I made to Winchester College where I assessed three boys aged fourteen, all former choristers at major London cathedrals. The boy below could phonate as low as E3 and produce usable tone down F#3 without suffering the laryngeal break that would likely occur for most boys of his age. The left shows the note D5 and the left G3. No change of tone could be detected perceptually.

Behnke and Browne agree that boys are to use their “head voice”, even to the lowest notes (or almost). They make an interesting claim that German alto boys at St. Cunibert’s in Cologne apparently demonstrated this to a fine art, in contrast to the raucous, “chest” tones of Welsh boys, said to “ruin many a fine choir in scores of Eisteddfodau” (Behnke and Browne, C1890:41). Stubbs agreed, stating either that adult male altos should be “well trained” or that boys should carry the “pure quality through the alto compass” (Stubbs 1888: 82). His fear was that trebles might lose their “sweetness of tone” by imitating the “unbearably coarse” sound of altos in lower “thick” register.

It seems that not that much had changed by 1940. Finn continued the onslaught on the boy alto “chest” voice, recording that:

The low, loud ‘chest tones’ with which so many boys sing is frequently judged as adequate for the alto part, and choirmasters are wont to refer to such singing as of boy-altos (Finn, 1939: 126).

Finns’ views on adolescent voices are interesting and of continuing relevance today. Somewhat out of step with today’s thinking, Finn reserved the term “counter-tenor” for the boy’s changing voice. McKenzie’s “alto-tenor” or Cooper’s later term “cambiata” would probably be closer correspondence to what Finn had in mind here. Larson credits Finn with reviving in America a Spanish practice of renaissance times – the adolescent alto, “little being known about the technique used for training this voice” (Larson, 1977: 53). Of more direct relevance for historically informed performance today Finn also refined an earlier classification of Stubbs who had divided men altos into two distinct types. There was first a “high, light tenor ranging from A3 – D5”. This voice, he asserted, had “chest and falsetto tones readily joined and so often blended by nature that it is impossible to detect a difference of register” (Stubbs 1908:14). Such voices he regarded as satisfactory, unlike the “so-called falsetto alto” in which “the colloquial and the singing tones do not correspond” (ibid.) Had he lived to read Andrew Parrott’s book, he might justifiably have congratulated himself in being somewhat ahead of his time.

Are boy sopranos needed for historically informed performance?

I have in this chapter, at some length demonstrated the extent to which boys can be, and certainly have been, altos. In the previous chapter, I made a strong case for the use of boys as means in historically informed performances of sixteenth century music. By the same token, there is an equal case for the use of boys as trebles in music of that period. The word treble, sometimes triplex or superius, is then used correctly in its historical sense as the higher of two boys’ parts and the highest in relation to the other parts. Any alternative such as “soprano” is quite out of place not least because it designates a recognised voice type and range. I do not think I have made a similarly strong case for boy altos. In today’s choirs boy altos would have to compete for a position against countertenors or female alto/contraltos, a competition they are unlikely to win. Any such competition is hardly justified on the grounds of historically informed performance since in the sixteenth century, choirs sang at lower pitches and the voices that sang the contra-tenor part were quite different to the modern countertenor. Use of boys as “means” can then be justified as the “authentic voice”. The situation with nineteenth century music is rather different. England, as we have seen, was becoming out of step with mainland Europe where composers were regularly writing parts for which the female contralto was the authentic voice.

We might conceivably mount an experimental performance with boy altos (and/or the “shrill piping” of a man) to demonstrate the shortcomings referred to by the writers cited in the previous section, but other than to satisfy curiosity, what would be the point? In this final section, I consider the extent to which the same argument might or might not apply to boys as sopranos.

Naïve Voices

The Cataloging and Metadata Committee of the Music Library Association of America recently concluded that we should separate the issue of vocal range from that of the gender of the singers, since “the accuracy of these terms for contemporary and historical use is questionable”. Predictably, this was reported in some quarters as yet another an act of “political correctness”, but the committee surely has made an entirely valid point.

Prior to the introduction of girls to previously boy only choirs (mainly in cathedrals) it was not uncommon to find both “treble” and “soprano” being used as gender words. Boys were definitely “trebles” and women were definitely “sopranos”. Young adolescent girls were not anything since they were not allowed to sing. To call a boy a “soprano” was tantamount to calling him a woman. Today’s widespread use of younger girls has forced a rethink by those who had previously used “treble” as a gender word. During early adolescence, both boys’ and girls’ voices have a naïve quality that distinguishes them quite clearly from adult voices of either sex. Girls begin to lose this naivety during middle adolescence, whilst boys do not generally begin to lose it until late adolescence despite the fact that their voices have dropped up to an octave in pitch. In spite of many hours pouring over spectrograms, it has hitherto proved impossible to provide a satisfactory acoustic definition of naivety. The work is ongoing. The only clearly distinguishing feature of a naïve voice, aside from its weaker overall power, is the lack of natural vibrato. It is this relatively easily perceived quality that has lead to it being preferred for ecclesiastical work.

There is no universally accepted definition of the word “soprano”. It is one of those words for which a definition is seldom sought since its meaning is assumed obvious to all who understand music. Wikipedia has it as “a type of classical female singing voice and has the highest vocal range of all voice types”. The enquirer is given a link to “sopranist” in order to find out about male voices with the ability to sing at similar pitches. The Encyclopaedia Britannica defines it principally as a woman’s voice but admits to the existence of boy sopranos, not very helpfully saying they are also called trebles. Apparently a castrato can be a soprano, but no mention of uncastrated adult males singing soprano is made.

Soprano generally refers to female voices, although it is also applied to boy sopranos (also called trebles) and to male castrati singers of the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries (Encylopaedia Britannica, accessed on-line October 2023).

It is mainly by convention that the top line in a English cathedral choir is today known as “treble”, though in Germany the word Knabensopran is more likely to be used for equivalent choirs. Intriguingly, the German Wikipedia definition of Knabensopran translates as “American English: boy soprano, British English: usually treble is the soprano voice of a boy until his voice breaks”. It would appear, in the absence of any clear objective criteria, that if a boy wishes to call himself a soprano, he may do so. An examination of recordings posted on YouTube reveals a somewhat arbitrary and random approach to the current use of the word “treble” or “soprano” by the boys themselves.

Historically, however, the many British boy artists who recorded during the first part of the twentieth century were almost always referred to as boy sopranos. Was this purely convention, or did it carry the expectation that the voice could substitute for, equal or even surpass that of a woman? It is with history that we are concerned here inasmuch as our interest is in the use of boys in historically informed performance.

Charles Stanford

Charles Stanford lived from 1852 to 1924, a close match, therefore for this period I am calling the early scientific age of singing. He is but one of several composers who could be chosen to represent the style of church music that prevailed at this time but is arguably amongst the most quintessential. The masterful service for double choir in A major (op.12) was a surprisingly early work, composed in 1880. The Bb service (op.10) was composed in 1879 but not published until 1902, whilst the G major service with the famous soprano solo in the Magnificat (op. 81) followed soon after. The Te Deum from the Bb service was orchestrated by Stanford for the coronation of Edward VIIth in 1902. Much as with the case of Bach, most of Stanford’s music was rapidly neglected after his death, the exception being his church music which has ever since been staple repertoire for cathedrals and parish choirs capable of performing it.

Although it is Stanford’s church music that is more familiar today, those writing about him at the time of his death up until a paper by Herbert Howells, who had known him for the last twelve years of his life, paid little attention to it. They focussed instead upon his many other now neglected works, his formidable work as a teacher and his Irish ancestry (Howells, 1952). I have as yet to uncover any conclusive evidence that supports any claim that Stanford, or any of his contemporaries for that matter, specifically intended his music to be sung by boys. The matter was quite simply of little to no concern in an era when boys would have been the norm. Stanford had more important things on his mind, such as the rise of a new generation of composers who saw nothing wrong in the use of parallel fifths (Dunhill, 1927).

Although boys were the norm, the contemporary evidence suggests that they were viewed as substitute women. Traditionalists expressing rage at the publication of Welch and Howard’s 2002 paper on gendered voice in the cathedral choir might have been surprised to read the following passage in Stubbs:

The larynges of boys and girls show no differences. They are anatomically alike. If, by way of experiment, we should train a boy and a girl from early childhood to use their voices gently, not only in singing, but also in conversation; if we should develop from the first, purity of tone and ease of production, their singing voices would be precisely similar. If hidden behind a screen, and made to sing, after such a course of training, no living expert could tell one voice from the other . . . If the boy’s voice is like the girl’s, and the girl’s like the woman’s, the analogy between all three is far from obscure. It is well, then, to teach boy choristers to copy, as closely as possible, the cultivated voices of women (Stubbs, 1888: 79).

Elsewhere:

What is the boy’s voice from the trainer’s standpoint? It is the Woman’s Voice. It would be a blessing if the term ‘boy voice’ could be abolished entirely. It insensibly tends to foster the idea that Nature fully intended the boy to have a singing-voice perfectly unique.

And in Curwen:

Shew him, first of all, that he has, as it were, two voices, and point out that he is required to use the voice that is most like a girl’s.

Samuel Wesley, expressed some frustration in 1849, opining simply that boys’ voices were a ‘poor substitute for the vastly superior quality and power of those of women’ (Wesley, 1849 in Day, 2000: 124) but was obliged to employ boys, nevertheless. The logical conclusion must be that the most authentic performance by a boy has to be the one that sounds nearest to that of a cultivated woman. Possibly this recent performance of the Magnificat in G by Pauline Arejola might serve as a reference example, though many others of differing quality and interpretation could have been chosen:

Pauline Arejola Stanford in G

A word of caution is needed here. A perverse tradition of women aiming to sound like boys has grown up, mainly in amateur church music, but in some professional choirs too. It is beyond the scope of this volume or my competency to comment on that, but I have eliminated from consideration any performances where there is any possibility of an amateur female soloist trying to sound like a boy. Arejola’s performance, in my view is that of a well produced woman’s voice that does not demonstrate the excessive vibrato, or worse “wobble” that might be a step too far. It can be compared with that of the boy at Cooksey singing in a strong M2 register during the late stages of voice change in Chapter 6.

Living Boy in M2 register (see Chapter 6)

The first recorded performance of the Magnificat in G known to exist was made in 1926 by the choir of St George’s Chapel Windsor. This was only two years after Stanford’s death and at least a decade before Bairstow condemned the tradition of starting with head notes or George Malcolm popularised the ragazzo voice. It is not an altogether unsafe assumption that what we hear from Windsor is close to the way boys sang in Stanford’s time. Unfortunately, the name of the boy soloist was never recorded. We have little idea as to his age, though he would probably have been one of the more senior.

Unknown Soloist, Windsor, 1926 (Courtesy Archive of Recorded Church Music)

Modern listeners are immediately struck by the fast tempo of the 1926 recording, particularly of the Gloria which seems to take off as though the men were in danger of missing closing time. An analysis of early and modern recordings by Elan Roten of Early Music Sources is highly instructive of the way performance practices of the early days of recordings differed from today (Roten, 2017). Tempi were generally faster and soloists less tied to the notated rhythms of the orchestra. The pitch in this Windsor recording is also almost a semitone higher, though we cannot be sure how much of this may have been due to the recording and playback speeds. The question that most concerns us here is that of whether the boys were singing with the “head tone” methods advocated by such as Stubbs, Howard and Curwen and so disliked by Edward Bairstow and George Malcolm. If they were, did this make them more soprano-like or more womanly than the norms of today?

For an answer to this question we might turn to perhaps one of the last exponents of these methods, George Thalben Ball, known as something of a reactionary far from averse to the use of the swell pedal in Bach. There exists a later archive BBC recording of Thalben Ball rehearsing the Temple choir in 1958. Two boys are asked to sing the opening of Walton’s Jubilate on their own. It has been possible to extract just their voices with no accompaniment and minimal background. From their photographs, we can judge them to be relatively young, certainly not near the completing puberty phase.

Robin

Bryan (Courtesy Archive of Recorded Church Music)

The phrase begins on G4 (O be joyful in the) and then leaps a fifth to D5 and a step up to E5 (Lord, all ye lands).

Spectra such as these are rarely found in boys today. They are dominated by a strong H2 and the higher partials, though weak, show clear evidence of a natural vibrato which is perceptible in both voices, particularly Robin’s. The difference in power between the G5 and the D5 is also considerable, as much as 28dB in the case of Robin whose power on “Lord” comes clearly from H2. This makes them historic voices. Does it make them soprano or “womanly”? Perhaps more so than most boys alive today though some degree of judgement is always going to enter into the equation. In Chapter 6, I described how Christopher Gabbitas preferred the tone of a present-day treble to the “very produced sound” of the sixteen-year-old Denis Barthel, recorded in 1932 and another of Thalben Ball’s boys, described by Gabbitas as “Ladies singing in Hollywood”.

A key issue here, of course, is polyphony. Stanford scholars, such as Rodmell, point out that though the bass line is always important it is nevertheless secondary to the soprano line, whilst the intermediate parts spend much of their time “filling in”. It is the soprano line that is the crowning glory and for which the voice profiles of the Temple church were so admirably suited. The naïve voice with its absence of vibrato is well suited to contrapuntal clarity, a significant consideration for George Malcolm and his successors, though perhaps not as necessary for historically informed performance as is commonly supposed (Roten, 2019). A present-day cathedral choir needs to be sufficiently versatile to render an Edwardian melodic line and a renaissance polyphonic line with equal effect, to say nothing of the exacting demands of composers since Britten. Their boys are of necessity “generalists” rather than specialists in the music of any particular era. Given that it is to such choirs that we must generally look to find the most capable boys, the chances of a boy specialising in the vocal style of any given era are remote. Also, we must not forget, the boys even in the best choirs are learners. For all their expertise and remarkable professionalism, they are children setting out on a journey. It is only right that they are given the best possible start and then left to make of it what they will.

Conclusion

In this and the previous chapter, I have pursued the somewhat novel idea that the absence of living boys from historically informed performance scholarship is a surprising omission. I have attempted to make the case for their inclusion and in so doing have come to appreciate what a difficult case it is to make. This is indeed an odd paradox, since boys have dominated Western choral singing for most of its history. I have not set out to perpetuate this domination, still less to promote spurious arguments of the “composers’ intentions” variety. I merely draw attention to the situation and leave it to others to reflect on the significance of the question. Another odd paradox, which we have seen in this chapter, is that the seeds of the current decline of the boy soprano or “treble” were sown during the very century of his apotheosis, for that was also the century that gave birth to the vocal science that has come to tell us that “boys sing too high for too long”. It is voice science at least as much as the liberation of female singers that has all but terminated the age of the teen boy soprano. It is even rarer in England now for boys to sing alto, other than as an expedient in a school choir. We have seen in this chapter that they once did, but mainly out of necessity. Women were not allowed to sing and adult male countertenors were either non-existent or of quality so poor that even the “raucous chest tones” of adolescent boys were sometimes thought preferable. It should be a sobering thought that the advent of the modern countertenor has done at least as much to displace boys as the advent of the female chorister.

In final conclusion, writing this book has been a very long journey. Many boys have been met along the way, and many of their teachers and choir conductors have participated or given of their time. For that I am extremely grateful because it has been essentially a personal journey. If it were other than that, there would be more books similar to this one, there would be more articles on boys in journals such as Early Music and a great deal more concern about the state of school music than there is. Nevertheless, I hope that what I have written will be of some value wherever there are boys who love to sing. Cohen’s concept of a “moral panic” has been referenced in diverse contexts over the years (Cohen, 2011). Perhaps “missing males in choral singing” is itself something of a moral panic? For all my efforts at involving more boys, I leave the status quo much as I found it. As for the question of how high boys should sing, have I answered that question over the last three decades? Of all the angles that have been examined, the one that it seems to me that endures and trumps even voice science is vocal agency, which gives us the answer “as high as they like”.