Beyond the Midvoice

A chorister has a love for what they learned when they were choristers. At the end of the day you can sing it back to front upside down the wrong way round by pure, you know kind of proximity to it, you’re gonna like it. (Nathan)

“Everybody who wants to be Aled Jones’s girlfriend is over sixty”. (Terry Wogan, 2005)

Introduction

Vocal agency is a term I have used for many years now. It means, quite simply, a boy’s own will with regard to his voice and singing. I have often stressed the fact that the voice is one of the most intimate and deeply personal parts of the body, yet at the same time one of the most public. Hardly anyone would dispute the general principle that a boy should have sovereignty over his own body, although in the case of minors there are varying degrees of compromise that are felt necessary. Where the voice of a young singer fits here is complex and interesting. Boys contracted to professional choirs may be allowed very little agency. Parental aspirations may dominate the lives of young recording artists. Teachers with strong opinions may see a boy as an opportunity to implement or prove their own theory. All of this reaches a state of considerable flux during the period of middle adolescence when two potent forces come into play. The change of voice has already been covered in considerable detail, but there are also considerable social and emotional changes associated with the rocky road to independence and ultimate adult autonomy.

Over the years, particularly as some of the young people recruited to my studies as little more than children have grown up, I have come to appreciate the years of middle and later adolescence a great deal more in all sorts of ways. It is a far from perfect analogy, but the years of middle adolescence are the years of gestation of the adult singer and it is possible to watch the new voice grow before it is ready to be born. Guidance of the singer during these years is a weighty responsibility but can be extremely rewarding. In this chapter, we are going to look at three very different paths taken during middle adolescence. We have already seen the extent to which normative development boundaries identified by Cooksey are stretched by circumstance. Here we will see that agency can create quite unexpected vocal identities. I begin with a brief definition of middle adolescence.

Middle adolescence

Much as there has been a secular trend to earlier puberty, so there has been a social trend to the later completion of adolescence. There is no universally agreed definition of adolescence and its boundaries but the earlier onset of puberty has resulted in quite frequent citation of the age of ten as the beginning of adolescence. The upper boundary of adolescence is now often extended to age 24 (Sawyer et al, 2018). This upward extension is largely, though not wholly, the result of changing social and economic conditions. It takes longer to achieve full economic independence with many more years being spent in education or part-time pre-career employment than in any previous century. Teen and youth culture, a phenomenon largely unknown before the 1950s, has become a major force marking out extended adolescence as distinct from adulthood. Studies of growth, however, also reveal now that full adult status is not achieved until after the teen years. Boys do not necessarily cease growing at age 18 or 19, and full skeletal maturity is not generally achieved until the early twenties. A key marker is full fusion of the iliac crest, with radiological studies revealing that this may not be achieved until between the ages of 23 and 25 (Batta et al, 2016).

The period of middle adolescence is similarly ill-defined. Ages fifteen to seventeen are commonly cited. The age of eighteen, when British teenagers achieve legal majority provides a ready-made boundary, although many “adult” activities such as joining the forces or marrying are available to sixteen-year-olds with parental consent. If we define middle adolescence as ages fifteen to seventeen for the purposes of analysing and classifying singing by young males, the critical age of fourteen when “boys are apt to change their voices” can be somewhat in limbo between early and middle adolescence.

The first serious stirrings of rebellion against parental control and deference to adult tastes begin during early adolescence, though boy singers aged between eleven and fourteen are generally content to exploit fully the capital they may have accrued through early success as “trebles”. The particular complications of finding a comfortable new vocal identity beyond this time cannot be underestimated. The view of cognitive neuroscience is that puberty gives a “nudge” to a developmental mismatch between prefrontal and subcortical brain regions which does much to dictate the course of middle and even late adolescence. The consequences are that decisions about singing will be made in an environment of risk taking, sensation seeking and heightened emotional reactivity (Knoll et al, 2015). Blakemore and Robbins (2012) stress that decision making in adolescence is subject to undue influence by social and emotional factors, particularly when in the company of peers and within contexts of heightened affectivity. Somehow, our young singer must manage the voices of middle adolescence during this difficult period of heightened vulnerability.

The voice during middle adolescence

In Chapters 4 and 5, we focussed mainly on what John Cooksey called the midvoice. It will be recalled that Cooksey recognised three stages of midvoice: midvoice I (stage 1 of change), midvoice II (stage 2) and midvoice IIa (stage 3). Midvoices I and II are the comfortable stages of early adolescence when any decline in phonational efficiency or acoustic resonance is offset by increased muscular control and musical experience. Most boys in their “golden year” of choristership are at one of the midvoice stages. Midvoice IIa marks more the end of early adolescence than the beginning of middle adolescence and we have devoted the lion’s share of our space so far to the question of how boys with high vocal capital have endeavoured to “hang on” to their former soprano or “treble” voices during midvoice IIa.

Many of them have done this against the odds during the time of most rapid voice deepening, the time when “breaking” of the speaking voice is recognised in ways such as ready perception of lowered speaking pitch, involuntary “cracks”, or the emergence of two distinct and often disconnected “singing voices”. Janus-like, the midvoice IIa, stage 3 of change, belongs comfortably neither to early adolescence nor middle adolescence. Vocally, there will be some fourteen-year-olds and even the occasional twelve-year-old who could be classified as mid-adolescent, but taking into account all other factors, particularly the social, it is those aged fifteen and above who represent the archetype of middle adolescence. In Cooksey’s terms, these are puberty stages 4 and 5, the “new baritone” and the “settling baritone”. In the three phase system, this is “completing puberty” or “post-mutation”.

Pitchwise, the ability to phonate a clear, resonant C3 (“tenor C”) that differs little in power from the notes immediately above it marks the end of the midvoice phase, though the emergence of a new vocal timbre across the entire modal range is equally significant. This new timbre, first heard in the lower notes of midvoice IIa, is difficult to describe. It is commonly referred to as “baritone” but the sound is quite different from an adult baritone voice. Equally it is different from a boy’s voice when singing low treble or alto notes.

Cooksey originally wrote that:

The quality is difficult to describe since resonation capabilities in the lower register extremes are not yet fully developed. The voice remains light but approximates the mid-baritone sound. It is huskier than the midvoice II sound [and] has a definite register lift point at middle C or D. (Cooksey, 1977a: 7)

In 1992 he wrote that:

The new baritone voice quality can be very firm and clear, but continues to sound immature, light, thin and lacking the richness of a typical adult male voice . . . there is very little vibrato . . . the voice lacks agility, flexibility, and often becomes heavy when fortissimo dynamics are called for. (Cooksey, 1992: 61- 2).

In 2000 he noted that “adult-like quality is not present in any stage of male adolescent voice transformation” and, further, that “all measurements were moving toward normal adult data, yet were still not close” (Cooksey, 2000: 728). Words such as “husky”, “light”, “immature” go some way towards describing the emerging baritone.

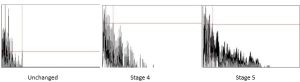

These unflattering descriptions present a new entrant to the middle adolescent years with something of a dilemma. For the boy who enjoyed a good career as a treble, it will now be some years, possibly even decades, before the next “peak performance”, at least if he is to be judged by adult standards. Before introducing some young men who are coping with stages 4 and 5, it will be helpful to understand a little more of what Cooksey meant. Reverting again to his original sonograms, we can see how these support his assertion that “nether the amount nor distribution of formant intensity above 4100 Hz was adult like in nature. Higher formants are weakest at midvoice IIa and gradually strengthen during stages 4 and 5”.

From Cooksey (2000: 728)

There is, however, a complication. The power spectrum of the unchanged voice is much simpler than either of the two baritone stages. This is not entirely clear in Cooksey’s examples. Female voices and boy’s unchanged voices, being about an octave higher than male voices have only half the number of harmonics available within keyboard range for resonance. Women may have only three formants from which to form their timbre (Bozeman, 2013: 32). We must assume that this is similar in boys’ voices. Good agreement with Cooksey’s original sonograms is apparent in the power spectra below. These are of the u vowel (“oo”) in the phrase hast “du mein Herz” from Schubert’s An die Musik sung by Max at the unchanged, new baritone and settling baritone stages.

Not worth trying?

Cooksey does not attempt an explanation of why new baritone voices fail to resonate higher harmonics. To the best of my knowledge, no other researcher has put forward a comprehensive explanation either. There are two possible reasons for this. First, few consider the mid-adolescent voice to be a subject of much interest. Second, even if we did understand better the why, there is arguably not that much we can do about it since it is the consequence of growth patterns that cannot be altered or interfered with. The “problem”, if that is what it is, will go away of its own accord once the growth process is complete. Edward Bairstow, writing in 1930, had a simple answer to the situation of most fourteen to sixteen-year-olds:

My experience is that if a boy uses his voice naturally and without forcing it, he never goes through a period when he cannot sing at all but, while in such cases it does very little harm for him to sing, it is no use him trying, as his voice is gradually changing in compass and in timbre (Bairstow, 1930, pp.11–12).

From Bairstow’s perspective the thin, weak timbre of the new baritone voice was of little use to a choir such as that of York Minster, still less the limited range and potential “cracks” of the Midvoice IIa. Bairstow had the luxury of a prestigious position enabling him to attract no shortage of applicants either for chorister or lay clerk positions. His attitude, however, has nothing to offer the very young choristers whose singing careers he was content to end with little compunction. How many of them might survive their redundancy notices and return to singing as adults was somebody else’s problem.

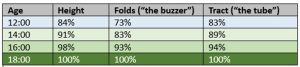

For those concerned with the mid-adolescent singer, what we know about the growth of the vocal tract is tantalising. The topic was introduced in Chapter 3 where I showed the percentage of adult height, weight, testis volume, fold length and tract length at key ages of childhood and adolescence. I have used in this table the terms “buzzer” and “tube” to refer to the fact that, were we able to hear the direct output of the larynx without any tract (“tube”) resonance, we would hear simply a buzz, albeit one rich in harmonic content. It is abundantly clear that folds 83% of adult length are sufficient to produce a buzz at adult pitch, but we are not getting the timbre.

(See Chapter 3 for full table)

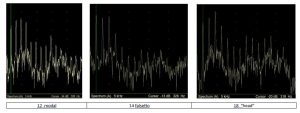

The right hand column above does not tell the full story. The table below has been constructed from Fitch and Giedd (1999) who conducted a ground breaking MRI study of 129 subjects aged between two and twenty five (53 female, 76 male). They determined the length of the vocal tract from glottis to lip plane using a technique that allowed segmentation into pharynx, velum, tongue dorsum, tongue blade, and lips. Strong correlations were found between height, weight and tract length that agreed well with Tanner staging of puberty.

(Derived from Fitch and Giedd, 1999: 1515)

The table shows that up until the mean age of 15, there is no difference between males and females. However, from age 15 upwards, males develop a disproportionately long pharynx relative to women and children. This would account for the resonance qualities of the adult male voice. However, if the sexual dimorphism in pharynx length only begins to appear at around age fifteen and does not fully develop until age eighteen, it is not unreasonable to suggest that a fourteen or fifteen year old is attempting to resonate adult pitches with a pharynx perhaps better suited to pitches an octave higher.

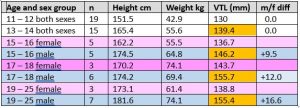

The figure below shows the same note, E4, sung to the three cardinal vowels i, a and u by a twelve-year-old modal voice at midvoice I, a fourteen year old falsetto voice and an eighteen year old modal voice at its “head” end.

The vowel formants, as we might expect are very similar in all three voices. The difference is in the higher harmonics which are strongest in the eighteen year old voice and weakest in the falsetto voice where the fourteen year old was struggling, finding it almost impossible to phonate this “devil’s note” in his modal voice. The figure below shows the Voce Vista display of the i vowel of the same three voices at pitch E4:

This gives us an idea of what is going on acoustically. We can see that the eighteen year old (an ex-chorister and trained singer) has a boost in the singers’ formant region between 2050 and 3300 Hz which is quite absent from the fourteen year old voice. The fourteen year old was also an experienced singer, but constrained at this age by the laws of nature. What is interesting is that the twelve year old also has a boost at just below 3000Hz. According to Howard and Williams (2014), “ring” harmonics in the twelve year old voice should be higher than the harmonics of an adult singer’s formant, as indeed they are in this example. It would be fascinating to carry out further research in this area. Meanwhile, we have to accept the fact that there is little we can do about weak resonance in working with mid-adolescent voices. We will now look at how two mid-adolescent boys have responded in very different ways.

Agency and Convention

In the previous chapter we looked at two “swansongs” associated with the Three Choirs Festival. The boys concerned had been making effective use of the strong M2 phonation that develops during stage 4 but ceased doing so after the summer holiday as convention dictated. We can be fairly confident that it is convention rather than peer pressure responsible, since young adolescents who sing high voice parts will have been defying peer pressure for some years already. We know that it was common for mid-adolescents to sing soprano in the years before the Second World War, whilst the exploits of some of the older Temple Church boys under Thalben-Ball were legendary. Cooksey did not dismiss the technical possibility of the mid-adolescent soprano, noting in 2000 that “tones sustained in the falsetto register showed lower ratios of noise components and were produced with less constriction of intrinsic laryngeal muscles” (op. cit. 727). He simply expected it not to happen, not repeating his original 1977 assertion that once they had passed the phase when the alto and soprano parts of SATB were too low, assignment must be to a tenor, bass, or baritone part. Perhaps the fact that a tenor part was not right either influenced his thinking between 1977 and 1992.

How long the M2 soprano is possible, and how it relates to the adult countertenor voice are technical questions that continue to interest me for the simple reason that in solo work at least, the alternative new baritone voice is seldom the source of real satisfaction for performer or listener that the previous “treble” or soprano was. Boys who are prepared to defy convention because of this are a source of interest and we shall shortly hear from one of them. Where, after all, would the world be if Alfred Deller had not been prepared to defy convention? The question is also of interest for the technical reasons discussed in the first part of this chapter. If it is true that the voice source and resonator are out of kilter in fourteen year olds, this is a situation that is gradually going to remedy itself towards the end of mid-adolescence. By age eighteen, most young men have a resonator that can do justice to what their voice source can produce. The converse is also true. A high male voice during late adolescence into adulthood is one in which a voice source has been trained to produce high frequency vibrations which must then be resonated in a pharynx that has grown to resonate lower frequencies. The result must, therefore, be different to that of a woman’s voice however it is perceived.

Eric, seventeen at the time of writing, describes himself as a “teen boy soprano”. Eric has been nicknamed “Le Rossignol” after Gérard Barbeau, an outstanding Canadian boy soprano of the 1950s (also described as a “coloratura treble”) who featured at age 14 in the film Le Rossignol et les cloches’ (The nightingale and the bells).

Le Rossignol

Tragically, Barbeau contracted a serious illness and died at the age of 24 after a period studying theology.

There can be little doubt that it is Eric’s own agency that is responsible for his unusual choice of vocal identity. His own words sum the topic of this chapter perfectly:

My baritone voice has no beauty, no low notes and no high. The soprano sound is wonderful, and I can see immediately on the face of people smiles, open mouth and very soon tears. They are submerged with emotion, that emotion that I am able to render with my soprano voice.

What he says about the baritone voice will be true of most mid-adolescent boys. It is an accurate observation born out by Cooksey’s work. His soprano performances are certainly spectacular and in middle adolescence he achieves a stage presence that would be beyond most smaller boys in early adolescence. He had been inspired as a child to sing like Derek Barsham, video-recording at age nine a “personal message and song to his hero Derek Barsham” some five years before the latter’s death.

Barsham was a former boy soprano who died in 2020, aged 89. He had been signed by Decca during the Second World War and recorded a number of items during that period, including Land of Hope and Glory which, to his surprise was played by the BBC a year later after the broadcast of Churchill’s victory speech. Tragically this recording has not survived. One that has is Holy City, recorded at the age of 14 (during a protracted session on account of repeated air raid warnings). It is in the key of Db, ranging from F4 – Ab5 and evidences, a strong, pure soprano tone that needs to be heard by those unfamiliar with skilled M2 phonation in middle adolescence.

Holy City

Barsham sang soprano until he was just seventeen but Beet (2022) contends that he could have continued for longer. The conservative opinions of various musicians were probably the decisive factor in terminating the soprano career. Perhaps a similar voice from a currently living boy might be that of Artem Fesko. In the multi-tracked sample below, he demonstrates a full two octave range from A#3 – A#5 with no weakness at either extremity (see also Nathan, Chapter 6). His SF0 at the time was 193 Hz.

Carol of the Bells

Eric has, of course, been asked about the technique he hopes will maintain a pure soprano range well beyond this phase. He provides the following simple answer. It has been a question of imitation.

Stephen Beet provided me with many recordings of other boys keeping their soprano voice till their 17th or later so I could believe it would happen [to me] by just keeping singing by the same way I always did since I am 6: using head voice (Beet, 2023).

I spoke to Eric by Zoom during the Covid lockdown. He was fifteen at the time and quite insistent that he wished to continue as a soprano as an adult. I put it to him that he perhaps meant “sopranist” (a countertenor with a soprano range). He was adamant, however, that he meant soprano. If, by “soprano” one means literally a woman’s voice, then in once sense at least only a woman can produce such a voice for the simple reason that an adult male has a vocal tract up to 16mm longer. There is, though, no “rule” that says a man may not call himself a soprano if he so wishes. It is a question of identity chosen through agency. Interestingly, Samuel Mariño, who has excited the opera world in recent years with his adult male soprano voice actually described himself as a sopranist in interview. Mariño owes his high voice in part to the refusal of medical intervention during puberty – another act of agency. It is quite clear that Eric went through an entirely normal puberty and speaks with a regular adult pitch, so there is no direct comparison to be made.

Frank Ivallo was featured in a Pathe newsreel in 1933 where he was described as “a novelty” and “the man with a woman’s voice”. There has naturally been speculation that he too had a condition similar to Mariño’s but his speaking voice was described as normal baritone and according to press reports appearing in October 1933, medical examinations found found no abnormalities.

The sound sample below is of the final bars of the well-known Giordani aria Caro mio ben recorded at the age of seventeen. I have selected the final bars because Eric chose to extend the colla voce fermata bar before the final cadence considerably, thus demonstrating both a remarkable lung capacity and a high degree of dynamic control. These are aspects of his singing that Eric has chosen to highlight in the past and evidence the fact that however one might choose to describe the voice, it is certainly not an adolescent male falsetto.

Caro mio ben, bars 77 – end

There are many recordings by women sopranos available for comparison. I have not included any here, partly because there are as many different interpretations as there are artists, and partly because to include even one might invite naïve and unhelpful comparison. If there is to be any comparison, it should perhaps be with Derek Barsham above, the voice Eric set out initially to emulate. Looking to the future, Eric has recently been accepted by the Paris Conservatoire for a course in baroque interpretation and repertoire. This marks him out as a potential specialist in early music. His remarkable power, lung capacity and dynamic control at audition resulted in questions arising about his potential in time to replicate castrato voices such as that of Farinelli (1705 – 1782).

There is a need for boys and young men who are prepared to defy convention. Some scholars have proposed that Bach’s Cantata 51 must have been sung by a woman because it is simply too difficult for a boy. Apart from the fact that a remarkable recording was made by the Drakensberg Boys Choir with Clint van der Linde as soprano, the availability today of a highly accomplished male soprano singer in late adolescence ought to excite some interest amongst those scholars who have looked into the ages of boys who sang soprano for Bach. Van der Linde is now a countertenor. Eric’s determination to remain a soprano will be a story requiring careful documentation.

Cai (real name) speaks for the undoubted majority of mid-adolescents coping with the transition from a former successful and high profile “treble” career. He had recorded a fine and well received treble album entitled Seren over two months in 2019 when he was aged 12:05. Success in the Chorister of the Year competition came two months later at 12:07. His final professional engagement was a re-recording of Suo Gan for the ITV series Pembrokshire Murders, at the age of 13:05. He had previously sung this Welsh lullaby a year earlier for his Seren album and again at the Chorister of the Year competition. The recording at 13:05 was a fifth lower than the original album recording and was to be the last time a treble timbre was to be heard. This almost exactly parallel’s Cormac’s performances of Gaelic Blessing at 11:05 and 13:08 (see previous chapter). Both boys had reached midvoice IIa and were facing a period without public performance or studio recording. I continue Cormac’s story in the next chapter but first there is a lot we can learn from Cai about the situation of the mid-adolescent.

I explored with him his response to the weak baritone problem shortly before his sixteenth birthday. Like many of his generation, he is tolerant of difference. A soprano beyond midvoice such as Eric’s is not for him, though he recognises as legitimate Eric’s different choice. Cai, though, would rather wait until his adult voice begins to mature.

I wouldn’t want to be [a teen soprano], because, obviously singing’s a big part of my life but there are a lot of other factors, in my life. I wouldn’t want to be, eighteen years old and still having like the voice of someone much younger. I mean, if he wants to do that, that’s totally fine, I guess.

His view that that Eric’s is the voice of someone much younger, though entirely understandable, is not born out by the sound sample above. However Eric’s voice might be described, it is not that of a much younger boy.

Cai did not, like Eric, have a vocal hero or role model. He had listened quite a lot to Jonas Kaufmann for opera “I want to listen to like the best to see how they sing it” but his concern was more with the present and his present situation. At this point his coach and mentor, Rob Lewis interjected that the “older choristers above him” had been more influential in forming him as a singer than any adult role model. Cai agreed, confirming the point I have made on a number of occasions that the greatest single source of learning for most choristers is through imitation of the older boys in the choir.

There had been no pressure on Cai to continue as a “treble” during midvoice IIa. I asked him for his “unvarnished” opinion of Bairstow’s pronouncement that it is “no use trying” to sing once the voice reached this stage.

I think you still need to be practising. You definitely shouldn’t stop. ‘Cos, even a month or like two weeks without singing, your technique can go, get a lot worse. As long as you’re not pushing it too much, like damaging your voice and you’re kind of letting it come on naturally I think it’s still important to keep singing with the range that you can without pushing anything.

Significantly, neither he nor Rob had heard of John Cooksey, so I presented them with brief details of Cooksey’s work and we looked closely together at his two descriptions of the stage 4 and 5 voice. Cai felt that he could relate well to the first new baritone classification, the first of the postmutational stages. Rob felt that he was just on the cusp of stage 5. I agreed with both their assessments, finding it interesting and encouraging that both had simultaneously and quickly recognized the accuracy and relevance of Cooksey’s descriptors.

Rob felt that puberty had begun by the time of the Seren treble album. He commented on “that thing where you get the slightly thicker vocal cords and stuff I’d say height of your treble voice that’s part of the changes that are happening”. This is almost certainly correct. SF0 was 187Hz during the Chorister of the Year interview. Cai felt he had begun to notice the effects of puberty on his voice at the very beginning of 2020, when he would have been aged 12:11.

Um, so I still had my high range in singing, um, middle range was starting to go so it would just be as consistent like some practices I’d just have some middle range notes that just weren’t there. I mean in terms of speaking it started to sound, started to get a bit deeper. Um, I could start to sing a bit lower as well. It wasn’t just my middle C, my bottom notes gained a few notes lower.

So your singing range went down a bit?

Yeah, range went down but I still had the high notes until a bit later on.

Both Cai and Rob made several comments about the retention of the high register at the same time as difficulties began to be experienced with the middle register and new notes started to appear at the bottom. Cai was not sure whether he could have sung in the two distinctly separate registers, stating that he never tried it. He understood falsetto as “using your head voice rather than your chest voice to sing higher notes” and brought up of his own volition the question of a third way of singing.

There’s not like a third way I can sing, I either use, I either use..(interruption)

At this point Rob interrupted, keen to stress that there will be “as your voice develops there will be much more of a third voice, a mix, of stuff.” This will be the case if Cai develops the classical techniques of a “chest” and “head” end to his modal voice and a seamless blend or cover into falsetto above that, but this is hard to do in the new baritone voice.

No recordings of Cai were made public between the ages of 13:05 and 15:05, although there was an ITV interview at age 13:11, by which time his SF0 was at 117 Hz. I asked him why he had decided to break silence at the age of fifteen and a half. He felt a loyalty to his audience, not least the people who had supported his album through crowdfunding. We talked about how a voice in middle adolescence could not possibly compare with a fully mature adult voice. Cai recognised this but had clearly been more bothered by his period of public silence.

Um, obviously I hadn’t shown people how I was doing, how my voice was going, um, I wanted to show them what I was up to, how, how my voice. . .

Who? Who do you want to show?

Well, my audience I guess, the people who follow me on YouTube, subscribers, um, just, I wanted to, I want, just to let people know that I’m still singing, um, I’m singing as a baritone. And then from here, when my voice develops even more, I can keep posting videos just to show my progression. I had to start somewhere though.

Music for a while. Age 15:05.

Recordings posted between the ages of 15:05 and 16:05 have generally been received sympathetically, reflecting perhaps something of a mutual loyalty, attitudes that show some understanding of the length of time it takes voices to mature, and the desire to encourage singers of the future.

Beautiful! A male singer, not screaming, but singing!

Please don’t overwork your voice too soon, it’s too good to push it at 15. You’ll need at least two more years of training to let it develop naturally!

So very lovely, and so courageous to come forth with a new range, new voice! As a singer who has not opened my mouth in over two years, I am so inspired and moved by your offering here! Continue to nurture your voice, your spirit, and always keep your expression true to your heart! Congratulations, Cai!

The most recent of these recordings at the time of writing is John Ireland’s Sea Fever, a “home video” posted in August 2023 but recorded during a concert at the Temple Church in December 2022. Cai would then have been 15:10. Several comments were very positive about the voice, but critical of the recording quality, which raises quite a significant question. When do we commit a “classical” new baritone voice to professional recording?

Cai’s commitment to “dead composers” seems to be in little doubt through his choice, not only of Ireland, but of Schubert, Purcell and Bach to show his new voice. His commitment to “classical” was tested in an unusual way when it was arranged for him to record a duet version of Karl Jenkins’s Ave Verum with the renowned Norwegian boy soprano Aksel Rykkvin. Aksel, by this time, was himself an emerging baritone and Rob felt it would be “nice to try and find a link from boy to baritone”. Before Aksel’s family would agree, however, it was necessary to give strong assurances about Cai’s classical credentials. In his mother’s words:

Yeah he [Aksel’s father] interviewed me quite heavily, because he wanted to make sure that they were . . . indistinct . . . yeah I wrote to him saying we’ve got the same values . . . he didn’t want Aksel to go down a different route because Cai had done some crazy pop thing.

A “crazy pop thing” seems unlikely for Cai, but the price to be paid is a wait of perhaps several years for the young adult voice that can do justice to classical repertoire. Cai clearly thinks the wait worthwhile, experimenting gently with his emerging new voice whilst he focuses on schoolwork and GCSE examinations.

Nathan’s voice we have already heard at ages nine and twelve. To the casual observer, this was a voice that “broke” overnight. In August he was singing treble, and in September, bass. We know that this is not how things work physically, so the explanation has to be one of agency. It is important that this is understood for there will have been many cases similar to Nathan’s over the years that could be wrongly interpreted as evidence that some voices “break” very quickly whilst others “break” much more slowly.

It is true, as we saw in Chapter 3, that intensity or tempo of puberty does vary, so the entire process of voice mutation does not proceed at a uniform rate among any given population of boys. However, we saw in the previous chapter that by the age of 13:11, Nathan had two “singing voices”, an M2 “treble” that he used for choir, and an M1 baritone that he did not use. It was the apparently straightforward switch from the one “singing voice” to the other that created the impression of an overnight “break”. The switch was the result of the exercise of agency in response to circumstance.

As a cathedral chorister, Nathan would have had little agency with regard to his singing range. For as long as he was contracted to the choir, he was required to sing “treble” by whatever means possible. On leaving the choir, he was then in a position to decide what to do with his voice. One opportunity that was open to him was to join the cathedral’s voluntary choir which at the time was still all-male. This he seized readily. At the age of twenty in a lengthy follow-up interview he told me that

A chorister has a love for what they learned when they were choristers. At the end of the day, you can sing it back to front upside down the wrong way round by pure, you know kind of proximity to it, you’re gonna like it.

He agreed with Cai’s observations that copying the older boys in the choir had been more influential than any potential adult role model singer. The “choral technique” learned in this manner is likely going to be with him for life. Doubtless high-level coaches such as Janice Chapman might frown at this point (see Chapter 2) but Nathan is following a career in medicine and does not aspire to be a professional soloist. He is obviously content with the rich choral life he follows, currently as a choral scholar at St Mary’s, the principal church in Swansea, and in his roles as president of the university choral society and university choral scholar.

Importantly his childhood socialisation into cathedral music has resulted in what will probably be a lifelong loyalty and interest in “dead composers”, but in keeping with many other ex-choristers his musical tastes have also broadened during middle and late adolescence. He listens to an Icelandic blues rock band called Kaleo. The “very unique [sic] kind of gravelly voice” of the lead singer has clearly impressed him and he has performed rock, but he nevertheless sings choral more often.

The nature of his abrupt treble to bass identity change and the vocal consequences for middle to late adolescence are an important part of the jigsaw I have been trying to piece together in this book. I first of all asked Nathan to confirm that the change was indeed as rapid as I have described.

But it did go straight from treble to bass over that summer holiday?

Went straight down yeh.

He was aware that the new voice might need to be treated lightly but had been motivated to use it because so many of his social connections were choral ones and “choral is what keeps me sane in all the work, in any work I’m doing”.

The switch to bass required little more than recognition of the M1, but this came at the expense of ignoring the M2. The result was a limited range, which was to trouble him for several years.

When I first started out I actually struggled with my range to be honest. It might have been because I did want to stay on as a chorister. When you’re a chorister and your voice is breaking you still push it. You know, keep your voice going. I don’t know whether that would have contributed.

He described how, although his range was limited, he felt buoyed up to continue because he felt he could still produce his voice quite well through the techniques he had learned as a chorister. Middle C remained his top note for several years but eventually, through continued use the range began slowly to expand upwards, eventually passing middle C to reach “on a good day” Es and Fs. Nathan clearly made no attempt to extend his mid-adolescent range through the combined use of M1 and M2 registers, though was quite emphatic that he does now have a usable falsetto.

Are you getting there (E4) without any use of falsetto? Is that the full voice?

Ds I can do with full voice, Es and can sometimes do with full voice, Fs are sort of a mixture. Um um, I’m finding that the, Ds and Es on a good day I can definitely get to an E without falsetto.

You’ve got a falsetto? You have got a falsetto voice that you can use?

Very much so. Very much so!

Nathan’s path to the adult voice has been evidently much the same as any other young man’s. The “devil’s note” of E4 is there, the M1 is at first weak at the upper end and lacking higher harmonics that gradually strengthen as the vocal tract reaches adult length. How different things might have been had his technique been dismantled and rebuilt by a knowledgeable singing teacher is an interesting question. The predominance of learning by imitation emerged as a theme. He described how his own father mimicked the voices of well-known singers and how he employed this technique at the age of seventeen. He had recorded two pieces for a “lockdown concert”, Vaughan Williams’ Silent Noon and Moon over Bourbon Street by Sting. The Vaughan Williams is the version for low voice in Db and ranges from Bb2 to Db4. The Sting piece has a more limited range with a tessitura centred on C4. The voice is certainly comfortable over these ranges, so by seventeen, initial difficulties with limited range were being overcome. Nathan is almost two years older than Cai in the samples below which represent the voice towards the end of middle adolescence. They can be compared with the recordings made at ages nine and twelve that mark the early and late boy chorister stages (see Chapter 6).

Moon Over Bourbon Street

Silent Noon

Perhaps the Sting song sounds more convincing than the Vaughan Williams one, further evidence that rewards come sooner in genres other than classical (see Cormac and Country Road, next chapter.)

Now to my ears you were able to produce to quite distinct singing styles, the Vaughan Williams and the Sting were sung with quite different voices would you agree?

Yes, absolutely.

And how’d you manage that?

It’s just basically listening and mimicry really. He doesn’t have training and stuff but my dad also, when he sings stuff, he’ll do a lot of mimicry of, of people he’ll listen to exactly you know he’ll just practice it until he feels like he’s getting a similar sound. Erm, I think maybe previous experience you know how to, the different ways you can manipulate (feeling his larynx)

Hmmm. Basically, you’re saying a Sting song, I want to sound like Sting. Is it as simple as that?

Yeh. Yeh.

Conclusion: realism and convention

Peer pressure is sometimes blamed for boys’ reluctance to sing in high voices, but I think this may be misplaced. It was not an issue with any of these case studies. A thirteen-year-old boy treble has already been ignoring peer pressure for two or three years as was amply repeatedly demonstrated in my 2009 book. Peer pressure is far from a phenomenon of our own times. It is recorded that Derek Barsham, in pre-Second World War days, experienced a form of bullying for his soprano voice that would not be acceptable today. He related the following incident to his biographer, Stephen Beet.

I would walk across the playground and someone would shout there’s that sissy singer, and I would be set upon and given a good bashing by a group of boys. . . . I decided to climb over the back wall and run along the railway embankment which took me close to where I lived. One day I found them waiting for me there so I ran the gauntlet and leapt through the hedge to the safety of my garden. As soon as I entered the house a brick flew through the window. (Barsham in Beet, 2005: 52).

Barsham sang soprano until the age of seventeen and there is no technical reason that those boys we have seen developing a strong soprano after their speaking voice had settled into baritone could not have continued until similar ages. To do so, however, would have meant going against strong conventions and one might reasonably ask to what purpose. In Eric’s case, the purpose might be to become a specialist adult interpreter of baroque, though when at the age of nine he first began to imitate Barsham he could hardly have understood or known about such a possibility.

Why would any young man in mid-adolescence desire, as Cai put it, to be “eighteen years old and still having the voice of someone much younger”? Eric provided an answer to this question. The appreciation of an unusual soprano voice, clearly not that of someone much younger, could be seen in the tears and smiles of his audiences, “submerged with emotion”. Eric had achieved a rare if not unique identity that made him stand out from age peers coping with the development of their new baritone voices. There is always a ready audience for the unconventional. Programmes such as Britain’s Got Talent amply demonstrate this. How many choral societies, though, would want to employ a boy soloist under the age of eighteen, with all that entails in health and safety legislation and the governance of child performers, when specialists in the mould of Emma Kirkby are available for historically informed performance? Would it be in any way practical to expect the soprano lines of adult choirs, whether professional or amateur, to be populated by male teenagers when it can be difficult enough to populate the lower parts?

For the majority of boys who have not devoted time to the development of exceptional techniques, it can indeed be a question of moving on because there are no convincing answers to such questions. Nearly all boys, however attached they may be to the voice that has defined their young lives, still aspire to a conventional place in the adult music world. For a good proportion, this will be as amateurs whilst other professions are followed. Some may yet harbour the ambition to repeat their childhood success as professional adult soloists but from conducting to composing, from studio management to music technology, to say nothing of teaching or research, or performing on an instrument, there are so many alternative career opportunities available.

Key points to take away from this chapter include:

- Case studies tend to support the view that boys’ “treble” careers peak after pubertal voice change has begun and the unchanged voice gives way to the midvoice.

- Increased muscular control, experience and cognitive maturity during the “midvoice” (stages 1 and 2) more than compensate for any decrease in phonational efficiency and an almost inevitable increase in air turbulence or “breathiness”.

- The “midvoice” is the most common voice stage during the period of early adolescence.

- The advent of the midvoice IIa (stage 3) signals the beginning of the transition from early to middle adolescence.

- It is not uncommon for accomplished singers and experienced choristers to continue as “trebles” during stage 3 whilst others are more likely either to stop singing or try out potential new ranges.

- Maintenance of a relative high closed quotient (CQ) is critical in maintaining what sounds like a good “treble head voice” during this time.

- Puberty stages 4 and 5 largely coincide with the period of middle adolescence. These are the two stages of the middle adolescent “emerging baritone”; the “new” and the “settling”.

- During stage 4, the new baritone voice particularly lacks body and sounds immature because harmonics in the higher formant regions are weak. It can be less satisfying for both performer and listener. For performers, this can result in mixed and conflicting emotions.

- These emotions must be managed during a difficult period characterised by increasing bids for independence and personal autonomy whilst there is simultaneously a mismatch between prefrontal and subcortical brain regions.

- A distinct M2 register first appears during stage 3 but strengthens considerably during stage 4. Occasionally, some boys have used this to produce a strong soprano which can be preferable to the weak baritone for a limited period for both performer and audience.

- Further research might explain better the weakness and immaturity of the new baritone voice. Incomplete development of vocal folds and disproportionate growth of voice source (larynx) and resonator (tract, particularly pharynx) is a plausible explanation since adult pitches are produced by the voice source but adult timbre is not produced by the vocal tract.

- The motivation to undertake such research is not strong. Expensive laboratory facilities are required and the voice will in any case begin to mature of its own accord due to natural growth ongoing during stage 5.

- A wide range of possibilities has been shown to exist during the middle adolescent phases through the strength of a boy’s will, his “vocal agency”. The majority of accomplished boy singers choose to sing gently and avoid high profile public performance until they are confident that their voice is beginning to mature. Exceptional cases of “teen boy sopranos”, more common in previous centuries, have engaged enthusiastic audiences.