1 Introduction to Lifespan Development

- Describe Baltes’ lifespan perspective with its key principles about development

- Describe human development and its three domains: physical, cognitive, and psychosocial development

- Differentiate conceptions of age and basic periods of human development

- Identify the key issues researchers investigate in the field of human development

- Explain the age period of emerging adulthood

- Differentiate emerging adulthood from adolescence and established adulthood

- Describe economic and cultural variations of emerging adulthood

Human Development or Lifespan Development is the scientific study of how people change, as well as how they remain the same, from conception to death. You will discover that the field, known more broadly as developmental science, examines changes and stability across multiple domains of psychological and social functioning. These include physical and neurophysiological processes, cognition, language, emotion, personality, moral, and psychosocial development, including our relationships with others.

Originally concerned with infants and children, the field has expanded to include adolescence, and more recently, aging and emerging adulthood to the entire lifespan. Previously, the message was once you turned 25, your development is essentially completed. Our academic knowledge of the lifespan has changed, and although there is still less research on adulthood than on childhood, adulthood is gaining increasing attention. This is particularly true now that the large cohort known as the “baby boomers” are beginning to enter late adulthood. The assumption that early childhood experiences dictate our future is also being called into question. Instead, we have come to appreciate that growth and change continue throughout life and experience continues to have an impact on who we are and how we relate to others. We now recognize that adulthood is a dynamic period of life marked by continued cognitive, social, and psychological development.

You will also discover that developmental psychologists investigate key questions, such as whether children are qualitatively different from adults or simply lack the experience that adults draw upon. Other issues they consider include the question of whether development occurs through the gradual accumulation of knowledge or through qualitative shifts from one stage of thinking to another, or if children are born with innate knowledge or figure things out through experience, and whether development is driven by the social context or something inside each child.

From these questions, you may already think developmental psychology is related to other applied fields. You are right. Developmental science informs many applied fields, including, educational psychology, developmental psychopathology, and intervention science. It also complements several other basic research fields in psychology including social psychology, cognitive psychology, and cross-cultural psychology. Lastly, it draws from the theories and research of several scientific fields including psychology, biology, sociology, health care, nutrition, and anthropology.

1.1 The Lifespan Perspective

As we have learned, human development refers to the physical, cognitive, and psychosocial changes and constancies in humans over time. There are various theories pertaining to each domain of development, and often theorists and researchers focus their attention on specific periods of development (with most traditionally focusing on infancy and childhood; some on adolescence). But isn’t it possible that development during one period affects development in other periods and that humans can grow and change across adulthood too? In this section, we’ll learn about development through the lifespan perspective, which emphasizes the multidimensional, interconnected, and ever-changing influences on development.

Lifespan development involves the exploration of biological, cognitive, and psychosocial changes and constancies that occur throughout the entire course of life. It has been presented as a theoretical perspective, proposing several fundamental, theoretical, and methodological principles about the nature of human development. An attempt by researchers has been made to examine whether research on the nature of development suggests a specific metatheoretical worldview. Several beliefs, taken together, form the “family of perspectives” that contribute to this particular view.

German psychologist Paul Baltes (1987), a leading expert on lifespan development and aging, developed one of the approaches to studying development called the lifespan perspective. This approach is based on several key principles:

- Development occurs across one’s entire life or is lifelong

- Development is multidimensional, meaning it involves the dynamic interaction of factors like physical, emotional, and psychosocial development

- Development is multidirectional and results in gains and losses throughout life

- Development is plastic, meaning that characteristics are malleable or changeable

- Development is influenced by contextual and socio-cultural influences

- Development is multidisciplinary

1) Development is lifelong

Lifelong development means that development is not completed in infancy or childhood or at any specific age; it encompasses the entire lifespan, from conception to death. The study of development traditionally focused almost exclusively on the changes occurring from conception to adolescence and the gradual decline in old age; it was believed that the five or six decades after adolescence yielded little to no developmental change at all. The current view reflects the possibility that specific changes in development can occur later in life, without having been established at birth. The early events of one’s childhood can be transformed by later events in one’s life. This belief clearly emphasizes that all stages of the lifespan contribute to the regulation of the nature of human development.

Many diverse patterns of change, such as direction, timing, and order, can vary among individuals and affect how they develop. For example, the developmental timing of events can affect individuals in different ways because of their current level of maturity and understanding. As individuals move through life, they are faced with many challenges, opportunities, and situations that impact their development. Remembering that development is a lifelong process helps us gain a wider perspective on the meaning and impact of each event (Baltes, 1987).

2) Development is multidimensional

By multidimensionality, Baltes is referring to the fact that a complex interplay of factors influences development across the lifespan, including biological, cognitive, and socioemotional changes. Baltes argues that a dynamic interaction of these factors is what influences an individual’s development. For example, in adolescence, puberty consists of physiological and physical changes with changes in hormone levels, the development of primary and secondary sex characteristics, alterations in height and weight, and several other bodily changes. But these are not the only types of changes taking place; there are also cognitive changes, including the development of advanced cognitive faculties such as the ability to think abstractly. There are also emotional and social changes involving regulating emotions, interacting with peers, and possibly dating. The fact that the term puberty encompasses such a broad range of domains illustrates the multidimensionality component of development.

3) Development is multidirectional

Baltes states that the development of a particular domain does not occur in a strictly linear fashion but that the development of certain traits can be characterized as having the capacity for both an increase and decrease in efficacy over the course of an individual’s life. If we use the example of puberty again, we can see that certain domains may improve or decline in effectiveness during this time. For example, self-regulation is one domain of puberty that undergoes profound multidirectional changes during the adolescent period. During childhood, individuals have difficulty effectively regulating their actions and impulsive behaviors. Scholars have noted that this lack of effective regulation often results in children engaging in behaviors without fully considering the consequences of their actions. Throughout puberty, neuronal changes modify this unregulated behavior by increasing the ability to regulate emotions and impulses. Inversely, the ability for adolescents to engage in spontaneous activity and creativity, both domains commonly associated with impulse behavior, decreases over the adolescent period in response to changes in cognition. Neuronal changes to the limbic system and prefrontal cortex of the brain, which begin in puberty lead to the development of self-regulation, and the ability to consider the consequences of one’s actions (though recent brain research reveals that this connection will continue to develop into early adulthood).

Extending on the premise of multidirectional, Baltes also argued that development is influenced by the “joint expression of features of growth (gain) and decline (loss)”[1] This relation between developmental gains and losses occurs in a direction to selectively optimize particular capacities. This requires the sacrificing of other functions, a process known as selective optimization with compensation. According to the process of selective optimization, individuals prioritize particular functions above others, reducing the adaptive capacity of particulars for specialization and improved the efficacy of other modalities.

The acquisition of effective self-regulation in adolescents illustrates this gain/loss concept. As adolescents gain the ability to effectively regulate their actions, they may be forced to sacrifice other features to selectively optimize their reactions. For example, individuals may sacrifice their capacity to be spontaneous or creative if they are constantly required to make thoughtful decisions and regulate their emotions. Adolescents may also be forced to sacrifice their fast reaction times toward processing stimuli in favor of being able to fully consider the consequences of their actions.

4) Development is plastic

Plasticity denotes intrapersonal variability and focuses heavily on the potentials and limits of the nature of human development. The notion of plasticity emphasizes that there are many possible developmental outcomes and that the nature of human development is much more open and pluralistic than originally implied by traditional views; there is no single pathway that must be taken in an individual’s development across the lifespan. Plasticity is imperative to current research because the potential for intervention is derived from the notion of plasticity in development. Undesired development or behaviors could potentially be prevented or changed.

As an example, recently researchers have been analyzing how other senses compensate for the loss of vision in blind individuals. Without visual input, blind humans have demonstrated that tactile and auditory functions still fully develop, and they can use tactile and auditory cues to perceive the world around them. One experiment designed by Röder et al. (1999) compared the auditory localization skills of people who are blind with people who are sighted by having participants locate sounds presented either centrally or peripherally (lateral) to them. Both congenitally blind adults and sighted adults could locate a sound presented in front of them with precision but people who are blind were clearly superior in locating sounds presented laterally. Currently, brain-imaging studies have revealed that the sensory cortices in the brain are reorganized after visual deprivation. These findings suggest that when vision is absent in development, the auditory cortices in the brain recruit areas that are normally devoted to vision, thus becoming further refined.

A significant aspect of the aging process is cognitive decline. The dimensions of cognitive decline are partially reversible, however, because the brain retains the lifelong capacity for plasticity and reorganization of cortical tissue. Mahncke et al. (2006) developed a brain plasticity-based training program that induced learning in mature adults experiencing age-related decline. This training program focused intensively on aural language reception accuracy and cognitively demanding exercises that have been proven to partially reverse age-related losses in memory. It included highly rewarding novel tasks that required attention control and became progressively more difficult to perform. In comparison to the control group, which received no training and showed no significant change in memory function, the experimental training group displayed a marked enhancement in memory that was sustained during the 3-month follow-up period. These findings suggest that cognitive function, particularly memory, can be significantly improved in mature adults with age-related cognitive decline by using brain plasticity-based training methods.

5) Development is contextual

In Baltes’ theory, the paradigm of contextualism refers to the idea that three systems of biological and environmental influences work together to influence development. Development occurs in context and varies from person to person, depending on factors such as a person’s biology, family, school, church, profession, nationality, and ethnicity. Baltes identified three types of influences that operate throughout the life course: normative age-graded influences, normative history-graded influences, and nonnormative influences. Baltes wrote that these three influences operate throughout the life course, their effects accumulate with time, and, as a dynamic package, they are responsible for how lives develop.

Normative age-graded influences: An age grade is a specific age group, such as toddler, adolescent, or senior. Humans experience particular age-graded social experiences (e.g., starting school) and biological changes (e.g., puberty).

Normative history-graded influences: The time period in which you are born shapes your experiences. A cohort is a group of people who are born at roughly the same period in a particular society. These people travel through life often experiencing similar historical changes at similar ages. History-graded influences include both environmental determinants (e.g., historical changes in the job market) and biological determinants (e.g., historical changes in life expectancy).

Non-normative influences: People’s development is also shaped by specific influences that are not organized by age or historical time, such as immigration, accidents, or the death of a parent. These can be environmental (e.g., parental mental health issues) or biological (e.g., life-threatening illness).

Which generation are you a part of?

| Generation | Years born between... |

|---|---|

| Silent Generation | 1928-1945 |

| Baby Boomers | 1946-1964 |

| Generation X | 1965-1980 |

| Millennials | 1981-1996 |

| Generation Z | 1995-2009 |

| Generation Alpha | 2010-2024 |

| Generation Beta | 2025-2039 |

The table contains information obtained from Beard and Bravo (2024) and Lally & Valentine-French (2019).

Other Contextual Influences on Development: Socioeconomic Status

Contextual perspectives, like the lifespan approach, highlight societal contexts that influence our development. An important societal factor is our social standing, socioeconomic status, or social class. Socioeconomic status (SES) is a way to identify families and households based on their shared levels of education, income, and occupation. While there is certainly individual variation, members of a social class tend to share similar privileges, opportunities, lifestyles, patterns of consumption, parenting styles, stressors, religious preferences, and other aspects of daily life. All of us born into a class system are socially located, and we may move up or down depending on a combination of both socially and individually created limits and opportunities.

Families with higher socioeconomic status usually are in occupations (e.g., attorneys, physicians, executives) that not only pay better but also grant them a certain degree of freedom and control over their job. Having a sense of autonomy or control is a key factor in experiencing job satisfaction, personal happiness, and ultimately health and well-being (Weitz, 2007). Those families with lower socioeconomic status are typically in occupations that are more routine, more heavily supervised, and require less formal education. These occupations are also more subject to job disruptions, including layoffs and lower wages.

The poverty level is an income amount established by the federal government that is based on a set of thresholds that vary by family size and composition (United States Census Bureau, 2023). If a family’s income is less than the government threshold, then that family is considered in poverty. Those living at or near the poverty level may find it extremely difficult to sustain a household with this amount of income. Poverty is associated with poorer health and a lower life expectancy due to poorer diet, less healthcare, greater stress, working in more dangerous occupations, higher infant mortality rates, poorer prenatal care, greater iron deficiencies, greater difficulty in school, and many other problems. Members of higher income status may fear losing that status, but the poor may have greater concerns over losing housing.

Today we are more aware of the variations in development and the impact that culture and the environment have on shaping our lives. Culture is the totality of our shared language, knowledge, material objects, and behavior. It includes ideas about what is right and wrong, what to strive for, what to eat, how to speak, what is valued, as well as what kinds of emotions are called for in certain situations. Culture teaches us how to live in a society and allows us to advance because each new generation can benefit from the solutions found and passed down from previous generations. Culture is learned from parents, schools, houses of worship, media, friends, and others throughout a lifetime. The kinds of traditions and values that evolve in a particular culture serve to help members function and value their society. We tend to believe that our own culture’s practices and expectations are the right ones. This belief that our own culture is superior is called ethnocentrism and is a normal by-product of growing up in a culture. It becomes a roadblock, however, when it inhibits understanding of cultural practices from other societies. Cultural relativity is an appreciation for cultural differences and the understanding that cultural practices are best understood from the standpoint of that particular culture.

Culture is an extremely important context for human development and understanding development requires being able to identify which features of development are culturally based. This understanding is somewhat new and still being explored. Much of what developmental theorists have described in the past has been culturally bound and difficult to apply to various cultural contexts. The reader should keep this in mind and realize that there is still much that is unknown when comparing development across cultures.

6) Development is multidisciplinary

Any single discipline’s account of development across the lifespan would not be able to express all aspects of this theoretical framework. That is why it is suggested explicitly by lifespan researchers that a combination of disciplines is necessary to understand development. Psychologists, sociologists, neuroscientists, anthropologists, educators, economists, historians, medical researchers, and others may all be interested and involved in research related to the normative age-graded, normative history-graded, and non-normative influences that help shape development. Many disciplines are able to contribute important concepts that integrate knowledge, which may ultimately result in the formation of a new and enriched understanding of development across the lifespan (Baltes, 1987).

1.2 Domains in Human Development

Human development refers to the physical, cognitive, and psychosocial development of humans throughout the lifespan. What types of development are involved in each of these three domains, or areas, of life? Physical development involves growth and changes in the body and brain, the senses, motor skills, and health and wellness. Cognitive development involves learning, attention, memory, language, thinking, reasoning, and creativity. Psychosocial development involves emotions, personality, and social relationships.

Physical Domain

Physical Domain

Many of us are familiar with the height and weight charts that pediatricians consult to estimate if babies, children, and teens are growing within normative ranges of physical development. We may also be aware of changes in children’s fine and gross motor skills, as well as their increasing coordination, particularly in terms of playing sports. But we may not realize that physical development also involves brain development, which not only enables childhood motor coordination but also greater coordination between emotions and planning in adulthood, as our brains are not done developing in infancy or childhood. Physical development also includes puberty, sexual health, fertility, menopause, changes in our senses, and primary versus secondary aging. Healthy habits with nutrition and exercise are also important at every age and stage across the lifespan.

Cognitive Domain

If we watch and listen to infants and toddlers, we can’t help but wonder how they learn so much so fast, particularly when it comes to language development. Then as we compare young children to those in middle childhood, there appear to be huge differences in their ability to think logically about the concrete world around them. Cognitive development includes mental processes, thinking, learning, and understanding, and it doesn’t stop in childhood. Adolescents develop the ability to think logically about the abstract world (and may like to debate matters with adults as they exercise their new cognitive skills!). Moral reasoning develops further, as does practical intelligence—wisdom may develop with experience over time. Memory abilities and different forms of intelligence tend to change with age. Brain development and the brain’s ability to change and compensate for losses is significant to cognitive functions across the lifespan, too.

Psychosocial Domain

Development in this domain involves what’s going on both psychologically and socially. Early on, the focus is on infants and caregivers, as temperament and attachment are significant. As the social world expands and the child grows psychologically, different types of play and interactions with other children and teachers become important. Psychosocial development involves emotions, personality, self-esteem, and relationships. Peers become more important for adolescents, who are exploring new roles and forming their own identities. Dating, romance, cohabitation, marriage, having children, and finding work or a career are all parts of the transition into adulthood. Psychosocial development continues across adulthood with similar (and some different) developmental issues of family, friends, parenting, romance, divorce, remarriage, blended families, caregiving for elders, becoming grandparents and great-grandparents, retirement, new careers, coping with losses, and death and dying.

As you may have already noticed, physical, cognitive, and psychosocial development are often interrelated, as with the example of brain development. We will be examining human development in these three domains in detail throughout the modules in this course, as we learn about infancy/toddlerhood, early childhood, middle childhood, adolescence, young adulthood, middle adulthood, and late adulthood development, as well as death and dying.

1.3 Conceptions of Age

Lifespan vs. Life expectancy

At this point, you might be asking yourself, “What is the difference between lifespan and life expectancy?” Lifespan, or longevity, refers to the maximum age any member of a species can reach under optimal conditions. For instance, the grey wolf can live up to 20 years in captivity, the bald eagle up to 50 years, and the Galapagos tortoise over 150 years (Smithsonian National Zoo, 2016). The longest recorded lifespan for a human was Jean Calment who died in 1994 at the age of 122 years, 5 months, and 14 days (Guinness World Records, n.d.). Life expectancy is the average number of years a person born in a particular time period can typically expect to live (Vogt & Johnson, 2016).

Chronological Age

Chances are you would answer this question based on the number of years since your birth, or what scientists call, your chronological age. Ever felt older than your chronological age? Some days we might “feel” like we are older, especially when we are not feeling well, are tired, or are stressed out. We might notice that a peer seems more emotionally mature than we are, or that they are physically more capable. Therefore, years since our birth is not the only way we can conceptualize age.

Chances are you would answer this question based on the number of years since your birth, or what scientists call, your chronological age. Ever felt older than your chronological age? Some days we might “feel” like we are older, especially when we are not feeling well, are tired, or are stressed out. We might notice that a peer seems more emotionally mature than we are, or that they are physically more capable. Therefore, years since our birth is not the only way we can conceptualize age.

Biological age

Another way developmental researchers can think about the concept of age is to examine how quickly the body is aging, this is considered your biological age. Several factors determine the rate at which our body ages; these include our nutrition, level of physical activity, sleeping habits, smoking, alcohol consumption, how we mentally handle stress, and the genetic history of our ancestors. There are just a few of the factors that impact our biological age.

Psychological age

Our psychologically adaptive capacity compared to others of our chronological age is our psychological age. This includes our cognitive capacity along with our emotional beliefs about how old we are. An individual who has cognitive impairments might be 20 years of age yet has the mental capacity of an 8-year-old. A 70-year-old might be traveling to new countries, taking courses at college, or starting a new business. Compared to others in our age group, we may be more or less active and excited to meet new challenges. Remember you are as young or old as you feel.

Social age

Social age

Our social age is based on the social norms of our culture and the expectations our culture has for people of our age group. Our culture often reminds us of whether we are “on target” or “off-target” for reaching certain social milestones, such as completing our education, moving away from home, having children, or retiring from work. However, there have been arguments that social age is becoming less relevant in the 21st century (Neugarten, 1979; 1996). If you look around at your fellow students at college you might notice more people who are older than traditional-aged college students, those 18 to 25. Similarly, the age at which people are moving away from the home of their parents, starting their careers, getting married or having children, or even whether they get married or have children at all, is changing.

Those who study lifespan development recognize that chronological age does not completely capture a person’s age. Our age profile is much more complex than this. A person may be physically more competent than others in their age group while being psychologically immature. So, how old are you? Or how old do you feel?

1.4 The Study of Lifespan Development

Childhood as a concept first emerged around the 17th century. In 1960, Philippe Ariès wrote a book called L’Enfant et la Vie Familiale sous l’Ancien Régime, which was translated into English as Centuries of Childhood in 1962. The book was significant both in that it recognized childhood as a social construction rather than as a biological given and in so doing, it founded the history of childhood as a serious field of study.

Ariès (1960) argued that childhood was not understood as a separate stage of life until the 15th century, and children were seen as little adults who shared the same traditions, games, and clothes. He said that parenting during the Middle Ages was largely detached, and there were not nuclear family bonds of love and concern. His account of childhood has since been widely criticized, but even today, Ariès (1960) remains the standard reference to the topic. He is most famous for his statement that “in medieval society, the idea of childhood did not exist”.

Attitudes towards children have evolved over time along with economic change and social advancement. Before the 17th century, children were generally considered weaker, more insignificant versions of adults. They were assumed to be subject to the same needs and desires as adults and to have the same vices and virtues as adults. Therefore, they dressed the same, were not warranted more privileges, worked the same hours, and received the same punishments for misdeeds. If they stole, they were hanged. If they worked hard and did well, they could achieve prosperity. Children were considered adults as soon as they could live alone.

At the time, this was society’s view of lifespan development. The only difference between children and adults was size. We now reject this medieval view, but how do we go about formulating contemporary theories? Our own personal theories about development are based on experiences, folklore, stories in the media, or built haphazardly on unverified observation. However, the theories presented in this course are more formal. They are based on prior findings and observations by psychologists and other researchers and provide a framework through which we can draw conclusions and make predictions about human behavior. These theories are subject to rigorous testing through research. In this text, we’ll discuss the major theoretical perspectives and theories that pertain to lifespan development. Each perspective emphasizes a different aspect of development and is just one means of studying the ever-evolving discipline of lifespan development. First, we’ll examine the issues that researchers study, which introduce assumptions that people hold about human development and underly the theoretical and empirical study of development.[3]

Issues of Lifespan Development

Below is a description of five of the major assumptions that researchers may hold when approaching the study of theories. While there are more than 5, these are the assumptions we will focus on in this textbook. These assumptions influence the way a researcher approaches designing and conducting a research study. Additionally, these assumptions influence how the public and the world view the process of human development.

- Nature versus Nurture: Why are you the way you are? As you consider some of your features (height, weight, personality, being diabetic, etc.), ask yourself whether these features are a result of heredity or environmental factors, or both. Chances are, you can see how both heredity and environmental factors (such as lifestyle, diet, and so on) have contributed to these features. For decades, scholars have carried on the “nature/nurture” debate. For any feature, those on the side of nature would argue that heredity plays the most important role in bringing about that feature. Those on the side of nurture would argue that one’s environment is most significant in shaping the way we are. This debate continues in all aspects of human development, and most scholars agree that there is a constant interplay between the two forces. It is difficult to isolate the root of any single behavior as a result solely of nature or nurture.

- Continuity versus Discontinuity: Is human development best characterized as a slow, gradual process, or is it best viewed as one of more abrupt change? The answer to that question often depends on which developmental theorist you ask and what topic is being studied. The theories of Freud, Erikson, Piaget, and Kohlberg are called stage theories. Stage theories or discontinuous development assume that developmental change often occurs in distinct stages that are qualitatively different from each other, and in a set, universal sequence. At each stage of development, children and adults have different qualities and characteristics. Thus, stage theorists assume development is more discontinuous. Others, such as the behaviorists, Vygotsky, and information processing theorists, assume development is a more slow and gradual process known as continuous development. For instance, they would see the adult as not possessing new skills, but more advanced skills that were already present in some form in the child. Brain development and environmental experiences contribute to the acquisition of more developed skills.

- Active versus Passive: How much do you play a role in your own developmental path? Are you at the whim of your genetic inheritance or the environment that surrounds you? Some theorists see humans as playing a much more active role in their development. Piaget, for instance, believed that children actively explore their world and construct new ways of thinking to explain the things they experience. In contrast, many behaviorists view humans as being more passive in the developmental process.

- Stability versus Change: How similar are you to how you were as a child? Were you always as outgoing or reserved as you are now? Some theorists argue that the personality traits of adults are rooted in the behavioral and emotional tendencies of the infant and young child. Others disagree and believe that these initial tendencies are modified by social and cultural forces over time.

- Universal versus Context Specific: A final assumption focuses on whether pathways of development are presumed to be (1) normative and universal, meaning that all people pass through them in the same sequence, or (2) differential and specific, meaning that a variety of different patterns and pathways of developmental change are possible depending on the individual and the context. Some theorists, like Piaget or Erickson, assume that everyone progresses through the same stages of cognitive development in the same order, or that everyone negotiates the same set of developmental tasks at about the same ages. Other theorists, who endorse lifespan or ecological systems approaches, believe that development can take on a wide variety of patterns and pathways, depending on the specific cultural, historical, and societal under which it unfolds.

1.5 Periods of Human Development

Think about the lifespan and make a list of what you would consider the basic periods of development. How many periods or stages are on your list? Perhaps you have three: childhood, adulthood, and old age. Perhaps, you have four: infant, childhood, adulthood, and old age. However, developmental psychologists often break the lifespan into eight stages, which are described in the table below. In addition, the topic of “Death and Dying” is usually addressed after late adulthood since overall, the likelihood of dying increases in later life (though individual and group variations exist). Death and dying will be the topic of our last chapter, although it is not necessarily a stage of development that occurs at a particular age.

The table below shows the developmental periods that will be explored in this text, starting with prenatal development, and continuing through late adulthood. Both childhood and adulthood are divided into multiple developmental periods. While both an 8-month-old and an 8-year-old are considered children, they have very different motor abilities, social relationships, and cognitive skills. Their nutritional needs are different, and their primary psychological concerns are also distinctive. The same is true of an 18-year-old and an 80-year-old, even though both are considered adults.

| Stage | Age Range |

|---|---|

| Prenatal | Conception to birth |

| Infancy & Toddlerhood | Birth to 2 years |

| Early Childhood | 2-6 years |

| Middle Childhood | 6-12 years |

| Adolsecence | 12-18 years |

| Emerging Adulthood | 18-29 years |

| Early or Established Adulthood | 30-45 years |

| Middle Adulthood | 45-65 years |

| Late Adulthood | 65 years to death |

1.6 Emerging Adulthood

A relatively new age period has surfaced, and most full-time college students fall into the developmental age period of “emerging adulthood”. Emerging adulthood is the period between the late teens and late twenties; ages 18-29 (Mehta et al., 2020; Society for the Study of Emerging Adulthood, 2016). Arnett (2000) argues that emerging adulthood is neither adolescence nor is it adulthood. Individuals in this age period have left behind the relative dependency of childhood and adolescence but have not yet taken on the responsibilities of adulthood. “Emerging adulthood is a time of life when many different directions remain possible when little about the future is decided for certain, when the scope of independent exploration of life’s possibilities is greater for most people than it will be at any other period of the life course” (Arnett, 2000, p. 469). Arnett identified five characteristics of emerging adulthood that distinguished it from adolescence and young adulthood (Arnett, 2006).

- Emerging adulthood is the age of identity exploration. In 1950, Erik Erikson proposed that it was during adolescence that humans wrestled with the question of identity. Yet, even Erikson (1968) commented on a trend during the 20th century of a “prolonged adolescence” in industrialized societies. Today, most identity development occurs during the late teens and early twenties rather than adolescence. It is during emerging adulthood that people explore their career choices and ideas about intimate relationships, setting the foundation for adulthood.

- Arnett (2000, 2006) described this time period as the age of instability. Exploration generates uncertainty and instability. Emerging adults change jobs, relationships, and residences more frequently than other age groups.

- Emerging adulthood is considered the age of self-focus. Being self-focused is not the same as being “self-centered.” Adolescents are more self-centered than emerging adults. Arnett (2006) reports that in his research, he found emerging adults to be very considerate of the feelings of others, especially their parents. They now begin to see their parents as people, not just as parents, something most adolescents fail to do. Nonetheless, emerging adults focus more on themselves, as they realize that they have few obligations to others and that this is the time when they can do what they want with their life.

- Emerging adulthood is the age of feeling in-between. When asked if they feel like adults, more 18- to 25-year-olds answer “yes and no” than do teens or adults over the age of 25 (Arnett, 2001). Most emerging adults have gone through the changes of puberty, are typically no longer in high school, and many have also moved out of their parents’ home. Thus, they no longer feel as dependent as they did as teenagers. Yet, they may still be financially dependent on their parents to some degree, and they have not completely attained some of the indicators of adulthood, such as finishing their education, obtaining a good full-time job, being in a committed relationship, or being responsible for others. It is not surprising that Arnett (2001) found that 60% of 18- to 25-year-olds felt that in some ways they were adults, but in some ways, they were not.

- Emerging adulthood is the age of possibilities. It is a time period of optimism as more 18- to 25-year-olds feel that they will someday get to where they want to be in life. Arnett (2000, 2006) suggests that this optimism is because these dreams have yet to be tested. For example, it is easier to believe that you will eventually find your soulmate when you have yet to have a serious relationship. It may also be a chance to change directions, for those whose lives up to this point have been difficult. The experiences of children and teens are influenced by the choices and decisions of their parents. If the parents are dysfunctional, there is little a child can do about it. In emerging adulthood, people can move out and move on. They have the chance to transform their lives and move away from unhealthy environments. Even those whose lives were happier and more fulfilling as children, now have the opportunity in emerging adulthood to become independent and make decisions about the direction they would like their life to take.

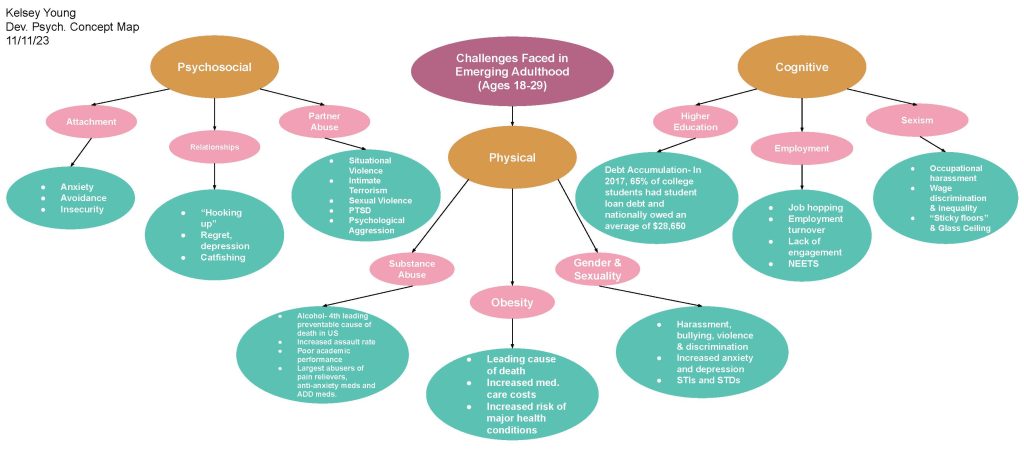

In the concept map below, a development psychology student constructed her map on the emerging adulthood age cohort by utilizing the three domains of development.

Socioeconomic Class and Emerging Adulthood

The theory of emerging adulthood was initially criticized as only reflecting upper-middle-class, college-attending young adults in the United States and not those who were working-class or poor (Arnett, 2016). Consequently, Arnett reviewed results from the 2012 Clark University Poll of Emerging Adults, whose participants were demographically similar to the United States population. Results primarily indicated consistencies across aspects of the theory, including positive and negative perceptions of the time period and views on education, work, love, sex, and marriage. Two significant differences were found, the first being that emerging adults from lower socioeconomic classes identified more negativity in their emotional lives, including higher levels of depression. Secondly, those in the lowest socioeconomic group were more likely to agree that they had not been able to find sufficient financial support to obtain the education they believed they needed. Overall, Arnett concluded that emerging adulthood exists wherever there is a period between the end of adolescence and entry into adult roles, but acknowledging social, cultural, and historical contexts was also important.

Cultural Variations

The five features proposed in the theory of emerging adulthood originally were based on research involving Americans between the ages 18 and 29 from various ethnic groups, social classes, and geographical regions (Arnett, 2004, 2016). To what extent does the theory of emerging adulthood apply internationally?

The answer to this question depends greatly on what part of the world is considered. Demographers make a useful distinction between the developing countries that comprise the majority of the world’s population and the economically developed countries that are part of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), including the United States, Canada, Western Europe, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand. The current population of OECD countries (also called developed countries) is 1.2 billion, about 18% of the total world population (United Nations Development Programme, 2011). The rest of the human population resides in developing countries, which have much lower median incomes, much lower median educational attainment, and much higher incidence of illness, disease, and early death. Let us consider emerging adulthood in other OECD countries as little is known about the experiences of 18-29-year-olds in developing countries.

The same demographic changes as described above for the United States have taken place in other OECD countries as well. This is true of participation in postsecondary education, as well as median ages for entering marriage and parenthood (UN Data, 2010). However, there is also substantial variability in how emerging adulthood is experienced across OECD countries. Europe is the region where emerging adulthood is the longest and most leisurely. The median ages for entering marriage and parenthood are near 30 in most European countries (Douglass, 2007). Europe today is the location of the most affluent, generous, and egalitarian societies in the world, in fact, in human history (Reifman, Arnett, & Colwell, 2007). Governments pay for tertiary education, assist young people in finding jobs, and provide generous unemployment benefits for those who cannot find work. In northern Europe, many governments also provide housing support. Emerging adults in European societies make the most of these advantages, gradually making their way to adulthood during their twenties while enjoying travel and leisure with friends.

The lives of Asian emerging adults in developed countries, such as Japan and South Korea, are in some ways similar to the lives of emerging adults in Europe and in some ways strikingly different. Like European emerging adults, Asian emerging adults tend to enter marriage and parenthood around the age of 30 (Arnett, 2011). Like European emerging adults, Asian emerging adults in Japan and South Korea enjoy the benefits of living in affluent societies with generous social welfare systems that provide support for them in making the transition to adulthood, including free university education and substantial unemployment benefits.

However, in other ways, the experience of emerging adulthood in Asian OECD countries is markedly different than in Europe. Europe has a long history of individualism, and today’s emerging adults carry that legacy with them in their focus on self-development and leisure during emerging adulthood. In contrast, Asian cultures have a shared cultural history emphasizing collectivism and family obligations.

Although Asian cultures have become more individualistic in recent decades, as a consequence of globalization, the legacy of collectivism persists in the lives of emerging adults. They pursue identity explorations and self-development during emerging adulthood, like their American and European counterparts, but within narrower boundaries set by their sense of obligations to others, especially their parents (Phinney & Baldelomar, 2011). For example, in their views of the most important criteria for becoming an adult, emerging adults in the United States and Europe consistently rank financial independence among the most important markers of adulthood. In contrast, emerging adults with an Asian cultural background especially emphasize becoming capable of supporting parents financially as among the most important criteria (Arnett, 2003; Nelson et al., 2004). This sense of family obligation may curtail their identity explorations in emerging adulthood to some extent, as they pay more heed to their parent’s wishes about what they should study, what job they should take, and where they should live than emerging adults do in the West (Rosenberger, 2007).

Footnotes

- Baltes, P. (1987). Theoretical propositions of life-span developmental psychology: On the dynamics between growth and decline. Developmental Psychology, 23(5), 611-626. ↵

- Catalano, R., Berglund, L., Ryan, J., Lonczak, H., & Hawkins, D. (2002). Positive youth development in the united states: Research findings on evaluations of positive youth development programs. Prevention & Treatment, 5(15), 27-28. ↵

- Thomas, R. M. (2001). Recent theories of human development Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. doi: 10.4135/9781452233673 ↵

References

Arnett, J.J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469-480. 10.1037/0003-066x.55.5.469

Arnett, J. J. (2001). Conceptions of the transitions to adulthood: Perspectives from adolescence to midlife. Journal of Adult Development, 8, 133–143.

Arnett, J. J. (2003). Conceptions of the transition to adulthood among emerging adults in American ethnic groups. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 100, 63–75.

Arnett, J. J. (2004). Conceptions of the transition to adulthood among emerging adults in American ethnic groups. In J. J. Arnett & N. Galambos (Eds.), Cultural conceptions of the transition to adulthood: New directions in child and adolescent development. Jossey-Bass.

Arnett, J. J. (2006). G. Stanley Hall’s adolescence: Brilliance and non-sense. History of Psychology, 9, 186–197.

Arnett, J.J. (2007). The long and leisurely route: Coming of age in Europe today. Current History, 106, 130–136.

Arnett, J. J. (2011). Emerging adulthood(s): The cultural psychology of a new life stage. In L.A. Jensen (Ed.), Bridging cultural and developmental psychology: New syntheses in theory, research, and policy (pp. 255–275). Oxford University Press.

Arnett, J. J. (2016). Does emerging adulthood theory apply across social classes? National data on a persistent question. Emerging Adulthood, 4(4), 227–235.

Baltes, P. (1987). Theoretical propositions of life-span developmental psychology: On the dynamics between growth and decline. Developmental Psychology, 23(5), 611-626. ↵

Beard, S. & Bravo, V. (2024, October 8). Gen Z, millennial, zillennial? Find your generation – and what it means – by year. USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/graphics/2024/10/08/generation-names-years-explained/74701974007/

Catalano, R., Berglund, L., Ryan, J., Lonczak, H., & Hawkins, D. (2002). Positive youth development in the United States: Research findings on evaluations of positive youth development programs. Prevention & Treatment, 5(15), 27-28. ↵

Duncan, G. J., & Magnuson, K. (Eds.). (2011). Whither opportunity: The nature and impact of early achievement skills, attention skills, and behavior problems. Sage.

Guinness World Records. (n.d.). Oldest person (ever). https://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/world-records/oldest-person

Hart, B., & Risley, T.R. (2003). The early catastrophe: The 30 million word gap by age 3. American Educator, 27(1), 4–9.

Lee, V. E., & Burkam, D. T. (2002). Inequality at the starting gate: Social background differences in achievement as children begin school. The Economic Policy Institute.

Mahncke, H. W., Connor, B. B., Appelman, J., Ahsanuddin, O. N., Hardy, J. L., Wood, R. A., … & Merzenich, M. M. (2006). Memory enhancement in healthy older adults using a brain plasticity-based training program: a randomized, controlled study. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103(33), 12523-12528.

Neugarten, B. L. (1979). Policy for the 1980s: Age or need entitlement? In J. P. Hubbard (Ed.), Aging: agenda for the eighties: A national journal issues book (pp. 48-52). Washington, DC: Government Research Corporation.

Neugarten, D. A. (Ed.) (1996). The meanings of age. The University of Chicago Press.

Risley, T. R., & Hart, B. (2006). Promoting Early Language Development. In N. F. Watt, C. Ayoub, R.H. Bradley, J. E. Puma, & W. A. LeBoeuf (Eds.), The crisis in youth mental health: Critical issues and effective programs, Vol. 4. Early intervention programs and policies (pp. 83–88). Praeger Publishers/Greenwood Publishing Group.

Reifman, A., Arnett, J.J., & Colwell, M.J. (2007). Emerging adulthood: Theory, assessment and application. Journal of Youth Development, 2(1), 37-48. https://doi.org/10.5195/jyd.2007.359

RoÈder, B., Teder-SaÈlejaÈrvi, W., Sterr, A., RoÈsler, F., Hillyard, S. A., & Neville, H. J. (1999). Improved auditory spatial tuning in blind humans. Nature, 400(6740), 162-166.

Smithsonian National Zoo. (2016). https://nationalzoo.si.edu/

Thomas, R. M. (2001). Recent theories of human development. Sage.

United States Census Bureau. (2023). Poverty. https://www.census.gov/topics/income-poverty/poverty/guidance/poverty-measures.html

Vogt, W.P., & Johnson, R.B. (2016). The SAGE dictionary of statistics and methodology. Sage.

Weitz, R. (2007). The sociology of health, illness, and health care: A critical approach. (4th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson.

Winerman, L. (2011). Closing the achievement gap: Could a 15-minute intervention boost ethnic-minority student achievement? Monitor on Psychology, 42(8), 36.

Media Attributions

- is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Triad © Kelly Soczka Steidinger is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- ai-generated-7833194_1280

- women-7301381_640

- Child Labor in Wisconsin in 1915 © Hine, Lewis Wickes, 1874-1940, is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Emerging Adulthood Concept Map © Kelsey Young is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- IMG_1580 © Kelly Soczka Steidinger is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license