14 Identity, Gender, and Sexuality

Learning Objectives

- Explain self-concept, identity, and personality

- Describe the eight stages of Erik Erikson’s Psychosocial Theory of Development

- Understand gender, gendered roles, and gender socialization

- Explain theories of gender development

- Describe gender in adulthood, including gender minorities

- Define sexuality and attraction

- Describe the brain areas and hormones responsible for sexual behavior

- Identify sexually transmitted infections/diseases

- Describe cultural views related to sexuality

- Describe research on sexual orientation

- Understand sexual orientation descrimination

- Understand sexuality in middle and late adulthood

In the grand exploration of human development, “identity” emerges as a fascinating puzzle, constantly evolving across our lifespan. It encompasses not only the conscious “me” we present to the world, but also the unconscious motivations, experiences, and beliefs that shape who we are. Imagine identity as a multifaceted jewel, each facet reflecting a different aspect: your cultural background, family dynamics, personal values, roles, gender, and passions. These elements interact and influence each other, creating a unique and ever-shifting picture of who you are. This course delves into the intricate processes that shape identity, exploring how biological, social, and cultural forces work together to paint this dynamic portrait. Through discussions and critical analysis, we’ll unpack Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development, examine the impact of social identities like race, gender, and sexuality, and explore the influence of personal experiences on self-concept. Ultimately, by understanding the multifaceted nature of identity, we gain a deeper appreciation for the complexities of human development and the journey of becoming (Gemini, 2024).

14.1 Self-Concept, Identity, & Personality

As you read in Chapter 13, self-concept is a process by which humans describe their internal and external qualities. However, the self-concept can also be conceptualized as how humans answer the questions “Who am I?” and “What makes me unique?” (Engelberg & Wynn, 2015). Additionally, the self-concept is a broad combination of self-beliefs that includes our self-esteem, roles in society, attitudes, abilities, and personality traits that are developed through social interactions, experiences, and reflections (Engelberg & Wynn, 2015). Whereas the concept of identity is used to refer to more specific aspects of our ‘self’ that we present to others in various social contexts and is the outward expression of our self-concept. Last of all, personality is long-standing patterns and traits that influence people to think, feel, and behave in specific ways (Speilman, Jenkins & Lovett, 2024). Personality integrates one’s temperament with cultural and environmental influences. Consequently, there are signs or indicators of these traits in childhood, but they become particularly evident when the person is an adult. Personality traits are integral to each person’s sense of self, as they involve what people value, how they think and feel about things, what they like to do, and what they are like almost every day throughout much of their lives. Self-concept, identity, and personality are all concepts that arise through social interactions, experiences, and maturation. In the next section, we will start by exploring how personality develops over the human lifespan.

14.2 Personality Development

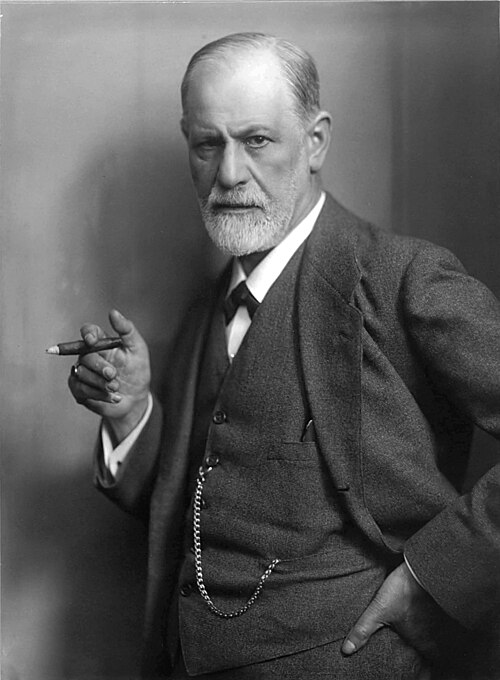

Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) believed that personality develops during early childhood. For Freud, childhood experiences shape our personalities and behavior as adults. Freud viewed development as discontinuous; he believed that each of us must pass through a series of stages during childhood and that if we lack proper nurturance and parenting during a stage, we may become stuck, or fixated, in that stage. Freud’s stages are called the stages of psychosexual development. According to Freud, children’s pleasure-seeking urges are focused on a different area of the body, called an erogenous zone, at each of the five stages of development: oral, anal, phallic, latency, and genital.

While most of Freud’s ideas have not found support in modern research, we cannot discount the contributions that Freud has made to the field of psychology. Psychologists today dispute Freud’s psychosexual stages as a legitimate explanation for how one’s personality develops, but what we can take away from Freud’s theory is that personality is shaped, in some part, by experiences we have in childhood. While Freud’s theory has been largely discredited, Erik Erikson’s psychosocial theory of personality development is more accepted and less controversial than Freud’s ideas.

Erik Erikson’s Psychosocial Theory

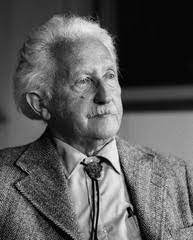

The psychodynamic theorist, the father of developmental psychology, Erik Erikson (1902-1994) was a student of Sigmund Freud’s and expanded on his theory of psychosexual development by emphasizing the importance of culture in parenting practices and motivations and adding three stages of adult development (Erikson, 1950; 1968).

As an art school dropout with an uncertain future, young Erik Erikson met Freud’s daughter, Anna Freud, while he was tutoring the children of an American couple undergoing psychoanalysis in Vienna. It was Anna Freud who encouraged Erikson to study psychoanalysis. Erikson received his diploma from the Vienna Psychoanalytic Institute in 1933, and as Nazism spread across Europe, he fled the country and immigrated to the United States that same year. Erikson later proposed a psychosocial theory of development, suggesting that an individual’s personality develops throughout the lifespan—a departure from Freud’s view that personality is fixed in early life. In his theory, Erikson emphasized the social relationships that are important at each stage of personality development, in contrast to Freud’s emphasis on erogenous zones. Erikson identified eight stages, each of which includes a conflict or developmental task. The development of a healthy personality and a sense of competence depends on the successful completion of each task.

Psychosocial Stages of Development

Erikson believed that we are aware of what motivates us throughout life and that the ego has greater importance in guiding our actions than does the id. We make conscious choices in life, and these choices focus on meeting certain social and cultural needs rather than purely biological ones. Humans are motivated, for instance, by the need to feel that the world is a trustworthy place, that we are capable individuals, that we can make a contribution to society, and that we have lived a meaningful life. These are all psychosocial problems.

Erikson’s theory is based on what he calls the epigenetic principle, encompassing the notion that we develop through an unfolding of our personality in predetermined stages and that our environment and surrounding culture influence how we progress through these stages. This biological unfolding in relation to our socio-cultural settings is done in stages of psychosocial development, where “progress through each stage is in part determined by our success, or lack of success, in all the previous stages.”[1]

Erikson described eight stages, each with a major psychosocial task to accomplish or a crisis to overcome. Erikson believed that our personality continues to take shape throughout our lifespan as we face these challenges. We will discuss each of these stages in greater detail when we discuss each of these life stages throughout the course. Here is an overview of each stage:

1) Trust vs. Mistrust (Hope) From birth to 12 months of age, infants must learn that adults can be trusted. This occurs when adults meet a child’s basic needs for survival. Infants are dependent upon their caregivers, so caregivers who are responsive and sensitive to their infant’s needs help their baby to develop a sense of trust; their baby will see the world as a safe, predictable place. Unresponsive caregivers who do not meet their baby’s needs can produce feelings of anxiety, fear, and mistrust; their baby may see the world as unpredictable. If infants are treated cruelly or their needs are not met appropriately, they will likely grow up with a sense of mistrust for people in the world.

2) Autonomy vs. Shame (Will) As toddlers (ages 1–3 years) begin to explore their world, they learn that they can control their actions and act on their environment to get results. They begin to show clear preferences for certain elements of the environment, such as food, toys, and clothing. A toddler’s main task is to resolve the issue of autonomy vs. shame and doubt by working to establish independence. This is the “me do it” stage. For example, we might observe a budding sense of autonomy in a 2-year-old child who wants to choose her clothes and dress herself. Although her outfits might not be appropriate for the situation, her input in such basic decisions influences her sense of independence. Erikson (1982) believed that toddlers should be allowed to explore their environment as freely as safety allows and in so doing will develop a sense of independence that will later grow to self-esteem, initiative, and overall confidence. If a caregiver is overly anxious about the toddler’s actions for fear that the child will get hurt or violate other’s expectation, the caregiver can give the child the message that he or she should be ashamed of their behavior and instill a sense of doubt in their own abilities. Parenting advice based on these ideas would be to keep toddlers safe but let them learn by doing. If denied the opportunity to act on their environment, she may begin to doubt her abilities, which could lead to low self-esteem and feelings of shame.

3) Initiative vs. Guilt (Purpose) Once children reach the preschool stage (ages 3–6 years), they are capable of initiating activities and asserting control over their world through social interactions and play. According to Erikson, preschool children must resolve the task of initiative vs. guilt. By learning to plan and achieve goals while interacting with others, preschool children can master this task. Initiative, a sense of ambition and responsibility, occurs when parents allow a child to explore within limits and then support the child’s choice. These children will develop self-confidence and feel a sense of purpose. To reinforce taking initiative, caregivers should offer praise for the child’s efforts and avoid being critical of messes or mistakes. Placing pictures of drawings on the refrigerator, purchasing mud pies for dinner, and admiring towers of Legos will facilitate the child’s sense of initiative. Those who are unsuccessful at this stage – with their initiative misfiring or stifled by over-controlling parents – may develop feelings of guilt.

4) Industry vs. Inferiority (Competence) During the elementary school stage (ages 7–12), children face the task of industry vs. inferiority. According to Erikson, children in middle and late childhood are very busy or industrious (Erikson, 1982). They are constantly doing, planning, playing, getting together with friends, and achieving. Children begin to compare themselves with their peers to see how they measure up. They either develop a sense of pride and accomplishment in their schoolwork, sports, social activities, and family life, or they feel inferior and inadequate because they feel that they don’t measure up. If children do not learn to get along with others or have negative experiences at home or with peers, an inferiority complex might develop into adolescence and adulthood.

5) Identity vs. Role Confusion (Fidelity) In adolescence (ages 12–18), children face the task of identity vs. role confusion. According to Erikson, an adolescent’s main task is developing a sense of self. Adolescents struggle with questions such as “Who am I?” and “What do I want to do with my life?” Along the way, most adolescents try on many different selves to see which ones fit; they explore various roles and ideas, set goals, and attempt to discover their adult selves. Adolescents who are successful at this stage have a strong sense of identity and can remain true to their beliefs and values in the face of problems and other people’s perspectives. When adolescents are apathetic, do not make a conscious search for identity, or are pressured to conform to their parents’ ideas for the future, they may develop a weak sense of self and experience role confusion. They will be unsure of their identity and confused about the future. Teenagers who struggle to adopt a positive role will likely struggle to find themselves as adults.

Additionally, Erikson saw this as a period of confusion and experimentation regarding identity and one’s life path. Marcia (1966[9]) described identify formation during adolescence as involving both decision points and commitments with respect to ideologies (e.g., religion, politics) and occupations. He described four identity statuses: foreclosure, identity diffusion, moratorium, and identity achievement. Foreclosure occurs when an individual commits to an identity without exploring options. Identity diffusion occurs when adolescents neither explore nor commit to any identities. Moratorium is a state in which adolescents are actively exploring options but have not yet made commitments. Identity achievement occurs when individuals have explored different options and then made identity commitments. The culmination of this exploration is a more coherent view of oneself. Those who are unsuccessful at resolving this stage may either withdraw further into social isolation or become lost in the crowd. However, more recent research, suggests that few leave this age period with identity achievement, and that most identity formation occurs during young adulthood (Côtè, 2006).

6) Intimacy vs. Isolation (Love) People in early adulthood (20s through early 40s) are concerned with intimacy vs. isolation. After we have developed a sense of self in adolescence, we are ready to share our life with others. However, if other stages have not been successfully resolved, young adults may have trouble developing and maintaining successful relationships with others. Erikson said that we must have a strong sense of self before we can develop successful intimate relationships. Adults who do not develop a positive self-concept in adolescence may experience feelings of loneliness and emotional isolation.

7) Generativity vs. Stagnation (Care) When people reach their 40s, they enter the time known as middle adulthood, which extends to the mid-60s. The social task of middle adulthood is generativity vs. stagnation. Generativity involves finding your life’s work and contributing to the development of others through activities such as volunteering, mentoring, and raising children. During this stage, middle-aged adults begin contributing to the next generation, often through caring for others; they also engage in meaningful and productive work that contributes positively to society. Those who do not master this task may experience stagnation and feel as though they are not leaving a mark on the world in a meaningful way; they may have little connection with others and little interest in productivity and self-improvement.

Research has demonstrated that generative adults possess many positive characteristics, including good cultural knowledge and healthy adaptation to the world (Peterson & Duncan, 2007). Additionally, women scoring high in generativity at age 52, were rated high in positive personality characteristics, satisfaction with marriage and motherhood, and successful aging at age 62 (Peterson & Duncan, 2007). Similarly, men rated higher in generativity at midlife were associated with stronger global cognitive functioning (e.g., memory, attention, calculation), stronger executive functioning (e.g., response inhibition, abstract thinking, cognitive flexibility), and lower levels of depression in late adulthood (Malone et al., 2016).

Erikson (1982) indicated that at the end of this demanding stage, individuals may withdraw as generativity is no longer expected in late adulthood. This releases elders from the task of caretaking or working. However, not feeling needed or challenged may result in stagnation, and consequently one should not fully withdraw from generative tasks as they enter Erikson’s last stage in late adulthood.

8) Integrity vs. Despair (Wisdom) From the mid-60s to the end of life, we are in the period of development known as late adulthood. Erikson’s task at this stage is called integrity vs. despair. He said that people in late adulthood reflect on their lives and feel either a sense of satisfaction or a sense of failure. People who feel proud of their accomplishments feel a sense of integrity, and they can look back on their lives with few regrets. However, people who are not successful at this stage may feel as if their life has been wasted. They focus on what “would have,” “should have,” and “could have” been. They may face the end of their lives with feelings of bitterness, depression, and despair.

Erikson’s theory was the first to propose a lifespan approach to development, and it has encouraged the belief that older adults still have developmental needs. Before Erikson’s theory, older adulthood was seen as a time of social and leisure restrictions and a focus primarily on physical needs (Barker, 2016). The current focus on aging well by keeping healthy and active helps to promote integrity. There are many avenues for those in late adulthood to remain vital members of society, and they will be explored next.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Erikson’s Theory

Erikson’s eight stages form a foundation for discussions on emotional and social development during the lifespan. Keep in mind, however, that these stages or crises can occur more than once or at different times of life. For instance, a person may struggle with a lack of trust beyond infancy. Erikson’s theory has been criticized for focusing so heavily on stages and assuming that the completion of one stage is a prerequisite for the next crisis of development. His theory also focuses on the social expectations that are found in certain cultures, but not in all. For instance, the idea that adolescence is a time of searching for identity might translate well in the middle-class culture of the United States, but not as well in cultures where the transition into adulthood coincides with puberty through rites of passage and where adult roles offer fewer choices.

By and large, Erikson’s view that development continues throughout the lifespan is very significant and has received great recognition. However, like Freud’s theory, it has been criticized for focusing on more men than women and for its vagueness, making it difficult to test rigorously.

Does personality change throughout adulthood?

Previously the answer was no, but contemporary research shows that although some people’s personalities are relatively stable over time, others are not (Lucas & Donnellan, 2011; Roberts & Mroczek, 2008). Longitudinal studies reveal average changes during adulthood in the expression of some traits (e.g., neuroticism and openness decrease with age and conscientiousness increases) and individual differences in these patterns due to idiosyncratic life events (e.g., divorce, illness). Longitudinal research also suggests that adult personality traits, such as conscientiousness, predict important life outcomes including job success, health, and longevity (Friedman et al., 1993; Roberts et al., 2007).

The Harvard Health Letter (2012) identifies research correlations between conscientiousness and lower blood pressure, lower rates of diabetes and stroke, fewer joint problems, being less likely to engage in harmful behaviors, being more likely to stick to healthy behaviors, and more likely to avoid stressful situations. Conscientiousness also appears related to career choices, friendships, and stability of marriage. Lastly, a person possessing both self-control and organizational skills, both related to conscientiousness, may withstand the effects of aging better and have stronger cognitive skills than one who does not possess these qualities.

14.3 Gender

Another important dimension of the self is gender. Preschool-aged children become increasingly interested in finding out the differences between boys and girls, both physically and in terms of what activities are acceptable for each. While two-year-olds can identify some differences and learn whether they are boys or girls, preschoolers become more interested in what it means to be male or female. Gender is the cultural, social, and psychological meanings associated with masculinity and femininity (Spears Brown & Jewell, 2018). A person’s sense of self as a member of a particular gender is known as gender identity. The development of gender identity appears to be due to an interaction among biological, social, and representational influences (Ruble et al., 2006). Gender roles, or the expectations associated with being male or female, are learned in one’s culture throughout childhood and into adulthood. Because gender is considered a social construct, meaning that it does not exist naturally, but is instead a concept that is created by cultural and societal norms, there are cultural variations on how people express their gender identity. For example, in American culture, it is considered feminine to wear a dress or skirt. However, in many Middle Eastern, Asian, and African cultures, dresses, or skirts (often referred to as sarongs, robes, or gowns) can be considered masculine. Similarly, the kilt worn by a Scottish male does not make him appear feminine in his culture.

Gender Socialization

Gender socialization focuses on what young children learn about gender from society, including parents, peers, media, religious institutions, schools, and public policies. Children learn about what is acceptable for females and males early, and in fact, this socialization may even begin the moment a parent learns that a child is on the way. Knowing the sex of the child can conjure up images of the child’s behavior, appearance, and potential on the part of a parent, and this stereotyping continues to guide perception throughout life. Consider parents of newborns, shown a 7-pound, 20-inch baby, wrapped in blue (a color designating males) describe the child as tough, strong, and angry when crying. Shown the same infant in pink (a color used in the United States for baby girls), these parents are likely to describe the baby as pretty, delicate, and frustrated when crying (Maccoby & Jacklin, 1987). Female infants are held more, talked to more frequently, and given direct eye contact, while male infant interactions are often mediated through a toy or activity.

As they age, sons are given tasks that take them outside the house and that have to be performed only on occasion, while girls are more likely to be given chores inside the home, such as cleaning or cooking that are performed daily. Sons are encouraged to think for themselves when they encounter problems and daughters are more likely to be assisted, even when they are working on an answer. Parents also talk to their children differently according to their gender. For example, parents talk to sons more in detail about science, and they discuss numbers and counting twice as often as with daughters (Chang et al., 2011).

Gender Role Intensification

During Adolescence, the process of puberty accentuates gender; role differences also accentuate for some teenagers. Some girls who excelled at math or science in elementary school may curb their enthusiasm and displays of success in these subjects for fear of limiting their popularity or attractiveness as girls (Taylor et al/, 1995; Sadker, 2004). Some boys who were not especially interested in sports previously may begin dedicating themselves to athletics to affirm their masculinity in the eyes of others. Some boys and girls who once worked together successfully on class projects may no longer feel comfortable doing so, or may now seek to be working partners, but for social rather than academic reasons. Such changes do not affect all youngsters equally, nor affect any one youngster equally on all occasions. An individual may act like a young adult on one day, but more like a child the next. How are these beliefs about behaviors and expectations based on gender transmitted to children?

Theories of Gender Development

One theory of gender development in children is social learning theory, which argues that behavior is learned through observation, modeling, reinforcement, and punishment (Bandura, 1997). Children are rewarded and reinforced for behaving in concordance with gender roles that have been presented to them since birth and punished for breaking gender roles. In addition, social learning theory states that children learn many of their gender roles by modeling the behavior of adults and older children and, in doing so, develop ideas about what behaviors are appropriate for each gender. Cognitive social learning theory also emphasizes reinforcement, punishment, and imitation, but adds cognitive processes. These processes include attention, self-regulation, and self-efficacy. Once children learn the significance of gender, they regulate their own behavior based on internalized gender norms (Bussey & Bandura, 1999).

Another theory is that children develop their own conceptions of the attributes associated with maleness or femaleness, which is referred to as gender schema theory (Bem, 1981). Once children have identified with a particular gender, they seek out information about gender traits, behaviors, and roles. This theory is more constructivist as children are actively acquiring their gender. For example, friends discuss what is acceptable for boys and girls, and popularity may be based on what is considered ideal behavior for their gender.

The developmental intergroup theory states that many of our gender stereotypes are so strong because we emphasize gender so much in culture (Bigler & Liben, 2007). Developmental intergroup theory postulates that adults’ heavy focus on gender leads children to pay attention to gender as a key source of information about themselves and others, to seek out any possible gender differences, and to form rigid stereotypes based on gender that are subsequently difficult to change.

Using Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory as a guide to gender development, children learn the social meanings of gender from adults and their culture starting at birth. Gender roles and expectations are especially portrayed in children’s toys, books, commercials, video games, movies, television shows, and music (Knorr, 2017). Therefore, when children make choices regarding their gender identification, expression, and behavior that may be contrary to gender stereotypes, it is important that they feel supported by the caring adults in their lives. This support allows children to feel valued, and resilient, and develop a secure sense of self (American Academy of Pediatricians, 2015).

Transgender Children

Many young children do not conform to the gender roles modeled by the culture and even push back against assigned roles. However, a small percentage of children actively reject the toys, clothing, and anatomy of their assigned sex and state they prefer the toys, clothing, and anatomy of the opposite sex. Approximately 0.3 percent of the United States population identify as transgender or identifying with the gender opposite their natal sex (Olson & Gülgöz, 2018). Some of these children may experience gender dysphoria or a marked incongruence between their assigned gender and their experienced/expressed gender (American Psychiatric Association, 2022). However, other children do not experience discomfort regarding their gender identity. Transgender adults have stated that they identify with the opposite gender as soon as they begin to talk (Russo, 2016).

Current research is now looking at those young children who identify as transgender and have socially transitioned. In 2013, a longitudinal study following 300 socially transitioned transgender children between the ages of 3 and 12 began (Olson & Gülgöz, 2018). Socially transitioned transgender children identify with the gender opposite to the one assigned at birth, and they change their appearance and pronouns to reflect their gender identity. Findings from the study indicated that the gender development of these socially transitioned children looked similar to the gender development of cisgender children, or those whose gender and sex assignment at birth matched. These socially transitioned transgender children exhibited similar gender preferences and gender identities as their gender-matched peers. Further, these children who were living every day according to their gender identity and were supported by their families exhibited positive mental health.

Some individuals who identify as transgender are intersex; that is born with either an absence or some combination of male and female reproductive organs, sex hormones, or sex chromosomes (Jarne & Auld, 2006). In humans, intersex individuals make up more than 150 million people, or about two percent of the world’s population (Blackless et al., 2000). There are dozens of intersex conditions, and intersex individuals demonstrate the diverse variations of biological sex. Some examples of intersex conditions include:

- Turner syndrome or the absence of, or an imperfect, second X chromosome

- Congenital adrenal hyperplasia or a genetic disorder caused by an increased production of androgens

- Androgen insensitivity syndrome or when a person has one X and one Y chromosome, but is resistant to the male hormones or androgens

Greater attention to the rights of children born intersex is occurring in the medical field, and intersex children and their parents should work closely with specialists to ensure these children develop positive gender identities.

How much does gender matter for children?

Starting at birth, children learn the social meanings of gender from adults and their culture. Gender roles and expectations are especially portrayed in children’s toys, books, commercials, video games, movies, television shows, and music (Khorr, 2017). Therefore, when children make choices regarding their gender identification, expression, and behavior that may be contrary to gender stereotypes, it is important that they feel supported by the caring adults in their lives. This support allows children to feel valued, be resilient, and develop a secure sense of self (American Academy of Pediatricians, 2015).

For many adults, the drive to adhere to masculine and feminine gender roles, or the societal expectations associated with being male or female, continues throughout life. In American culture, masculine roles have traditionally been associated with strength, aggression, and dominance, while feminine roles have traditionally been associated with passivity, nurturing, and subordination. Men tend to outnumber women in professions such as law enforcement, the military, and politics, while women tend to outnumber men in care-related occupations such as childcare, healthcare, and social work. These occupational roles are examples of stereotypical American male and female behavior, derived not from biology or genetics, but from our culture’s traditions. Adherence to these roles may demonstrate fulfillment of social expectations, however, not necessarily personal preferences (Diamond, 2002).

Consequently, many adults are challenging gender labels and roles, and the long-standing gender binary; that is, categorizing humans as only female and male, has been undermined by current psychological research (Hyde et al., 2019). The term gender now encompasses a wide range of possible identities, including cisgender, transgender, agender, genderfluid, genderqueer, gender nonconforming, bigender, pangender, ambigender, non-gendered, intergender, and Two-spirit which is a modern umbrella term used by some indigenous North Americans to describe gender-variant individuals in their communities (Carroll, 2016). Hyde et al. (2019) advocates for a conception of gender that stresses multiplicity and diversity and uses multiple categories that are not mutually exclusive.

Gender Minority Discrimination

Gender-nonconforming people are much more likely to experience harassment, bullying, and violence based on their gender identity; they also experience much higher rates of discrimination in housing, employment, healthcare, and education (Borgogna et al., 2019; National Center for Transgender Equality, 2015). Transgender individuals of color face additional financial, social, and interpersonal challenges, in comparison to the transgender community as a whole, as a result of structural racism. Black transgender people reported the highest level of discrimination among all transgender individuals of color. As members of several intersecting minority groups, transgender people of color, and transgender women of color in particular, are especially vulnerable to employment discrimination, poor health outcomes, harassment, and violence. Consequently, they face even greater obstacles than white transgender individuals and cisgender members of their own race.

Gender Minority Status and Mental Health

Using data from over 43,000 college students, Borgona et al. (2019) examined mental health differences among several gender groups, including those identifying as cisgender, transgender and gender nonconforming. Results indicated that participants who identified as transgender and gender nonconforming had significantly higher levels of anxiety and depression than those identifying as cisgender. Bargona et al. (2019) explained the higher rates of anxiety and depression using the minority stress model, which states that an unaccepting social environment results in both external and internal stress which contributes to poorer mental health. External stressors include discrimination, harassment, and prejudice, while internal stressors include negative thoughts, feelings, and emotions resulting from one’s identity. Borgona et al. (2019) recommend that mental health services that are sensitive to both gender minority and sexual minority statuses be available.

Transgender children may, when they become an adults, alter their bodies through medical interventions, such as surgery and hormonal therapy, so that their physical being is better aligned with gender identity. However, not all transgender individuals choose to alter their bodies or physically transition. Many will maintain their original anatomy but may present themselves to society as a different gender, often by adopting the dress, hairstyle, mannerisms, or other characteristics typically assigned to a certain gender. It is important to note that people who cross-dress or wear clothing that is traditionally assigned to the opposite gender, do not necessarily identify as transgender (though some do). Cross-dressing is typically a form of self-expression, entertainment, or personal style, and not necessarily an expression of one’s gender identity.

14.4 Sexuality

Human sexuality refers to people’s sexual interest in and attraction to others, as well as their capacity to have erotic experiences and responses. Sexuality may be experienced and expressed in a variety of ways, including thoughts, fantasies, desires, beliefs, attitudes, values, behaviors, practices, roles, and relationships. These may manifest themselves in biological, physical, emotional, social, or spiritual aspects. The biological and physical aspects of sexuality largely concern the human reproductive functions, including the human sexual response cycle and the basic biological drive that exists in all species. Emotional aspects of sexuality include bonds between individuals that are expressed through profound feelings or physical manifestations of love, trust, and care. Social aspects deal with the effects of human society on one’s sexuality, while spirituality concerns an individual’s spiritual connection with others through sexuality. Sexuality also impacts and is impacted by cultural, political, legal, philosophical, moral, ethical, and religious aspects of life.

The Sexual Response Cycle

Sexual motivation, often referred to as libido, is a person’s overall sexual drive or desire for sexual activity. This motivation is determined by biological, psychological, and social factors. In most mammalian species, sex hormones control the ability to engage in sexual behaviors. However, sex hormones do not directly regulate the ability to copulate in primates (including humans); rather, they are only one influence on the motivation to engage in sexual behaviors. Social factors, such as work and family, also have an impact, as do internal psychological factors like personality and stress. Sex drive may also be affected by hormones, medical conditions, medications, lifestyle stress, pregnancy, and relationship issues.

The sexual response cycle is a model that describes the physiological responses that take place during sexual activity. According to Kinsey, Pomeroy, and Martin (1948), the cycle consists of four phases: excitement, plateau, orgasm, and resolution. The excitement phase is the phase in which the intrinsic (inner) motivation to pursue sex arises. The plateau phase is the period of sexual excitement with increased heart rate and circulation that sets the stage for orgasm. Orgasm is the release of tension, and the resolution period is the unaroused state before the cycle begins again.

The Brain and Sex

The brain is the structure that translates the nerve impulses from the skin into pleasurable sensations. It controls nerves and muscles used during sexual behavior. The brain regulates the release of hormones, which are believed to be the physiological origin of sexual desire. The cerebral cortex, which is the outer layer of the brain that allows for thinking and reasoning, is believed to be the origin of sexual thoughts and fantasies. Beneath the cortex is the limbic system, which consists of the amygdala, hippocampus, cingulate gyrus, and septal area. These structures are where emotions and feelings are believed to originate, and they are important for sexual behavior.

The hypothalamus is the most important part of the brain for sexual functioning. This is the small area at the base of the brain consisting of several groups of nerve-cell bodies that receive input from the limbic system. Studies with lab animals have shown that the destruction of certain areas of the hypothalamus causes a complete elimination of sexual behavior. One of the reasons for the importance of the hypothalamus is that it controls the pituitary gland, which secretes hormones that control the other glands of the body.

Hormones

Several important sexual hormones are secreted by the pituitary gland. Oxytocin, also known as the hormone of love, is released during sexual intercourse when an orgasm is achieved. Oxytocin is also released in females when they give birth or are breastfeeding; it is believed that oxytocin is involved with maintaining close relationships. Both prolactin and oxytocin stimulate milk production in females.

Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) is responsible for ovulation in females by triggering egg maturity; it also stimulates sperm production in males. Luteinizing hormone (LH) triggers the release of a mature egg in females during the process of ovulation.

In males, testosterone appears to be a major contributing factor to sexual motivation. Vasopressin is involved in the male arousal phase, and the increase of vasopressin during erectile response may be directly associated with increased motivation to engage in sexual behavior.

The relationship between hormones and female sexual motivation is not as well understood, largely due to the overemphasis on male sexuality in Western research. Estrogen and progesterone typically regulate motivation to engage in sexual behavior for females, with estrogen increasing motivation and progesterone decreasing it. The levels of these hormones rise and fall throughout a woman’s menstrual cycle. Research suggests that testosterone, oxytocin, and vasopressin are also implicated in female sexual motivation in similar ways as they are in males, but more research is needed to understand these relationships.

Sexual Responsiveness Peak

Men and women tend to reach their peak of sexual responsiveness at different ages. For men, sexual responsiveness tends to peak in the late teens and early twenties. Sexual arousal can easily occur in response to physical stimulation or fantasizing. Sexual responsiveness begins a slow decline in the late twenties and into the thirties, although a man may continue to be sexually active. Through time, a man may require more intense stimulation to become aroused. Women often find that they become more sexually responsive throughout their 20s and 30s and may peak in the late 30s or early 40s. This is likely due to greater self-confidence and reduced inhibitions about sexuality.

Sexually Transmitted Infections

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs), also referred to as sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) or venereal diseases (VDs), are illnesses that have a significant probability of transmission by means of sexual behavior, including vaginal intercourse, anal sex, and oral sex. Some STIs can also be contracted by sharing intravenous drug needles with an infected person, as well as through childbirth or breastfeeding. Common STIs include:

- chlamydia;

- herpes (HSV-1 and HSV-2);

- human papillomavirus (HPV);

- gonorrhea;

- syphilis;

- trichomoniasis;

- HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) and AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome).

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2014), there was an increase in the three most common types of STDs in 2014. These include 1.4 million cases of chlamydia, 350,000 cases of gonorrhea, and 20,000 cases of syphilis. Those most affected by STDS include those younger, gay/bisexual males, and females. The most effective way to prevent transmission of STIs is to practice safe sex and avoid direct contact of skin or fluids which can lead to transfer with an infected partner. Proper use of safe-sex supplies (such as male condoms, female condoms, gloves, or dental dams) reduces contact and risk and can be effective in limiting exposure; however, some disease transmission may occur even with these barriers.

Sexuality in Middle and Late Adulthood

Sexuality is an important part of people’s lives at any age, and many older adults are very interested in staying sexually active (Dimah & Dimah, 2004). According to the National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior (NSSHB) (Center for Sexual Health Promotion, 2010), 74% of males and 70% of females aged 40-49 engaged in vaginal intercourse during the previous year, while 58% of males and 51% of females aged 50-59 did so.

Despite these percentages indicating that middle adults are sexually active, age-related physical changes can affect sexual functioning. For women, decreased sexual desire and pain during vaginal intercourse because of menopausal changes have been identified (Schick et al., 2010). A woman may also notice less vaginal lubrication during arousal which can affect overall pleasure (Carroll, 2016). Men may require more direct stimulation for an erection and the erection may be delayed or less firm (Carroll, 2016). As previously discussed, men may experience erectile dysfunction or experience a medical condition (such as diabetes or heart disease) that impacts sexual functioning. Couples can continue to enjoy physical intimacy and may engage in more foreplay, oral sex, and other forms of sexual expression rather than focusing as much on sexual intercourse.

The risk of pregnancy continues until a woman has been without menstruation for at least 12 months, however, couples should continue to use contraception. People continue to be at risk of contracting sexually transmitted infections, such as genital herpes, chlamydia, and genital warts. In 2014, 16.7% of the country’s new HIV diagnoses (7,391 of 44,071) were among people 50 and older, according to the CDC (2014e). This was an increase from 15.4% in 2005. Practicing safe sex is important at any age, but unfortunately, adults over the age of 40 have the lowest rates of condom use (Center for Sexual Health Promotion, 2010). This low rate of condom use suggests the need to enhance education efforts for older individuals regarding STI risks and prevention. Hopefully, when partners understand how aging affects sexual expression, they will be less likely to misinterpret these changes as a lack of sexual interest or displeasure in the partner and more able to continue to have satisfying and safe sexual relationships.

According to Kane (2008), older men and women are often viewed as genderless and asexual. There is a stereotype that elderly individuals no longer engage in sexual activity and when they do, they are perceived to have committed some kind of offense. These ageist myths can become internalized, and older people have a more difficult time accepting their sexuality (Gosney, 2011). Additionally, some older women indicate that they no longer worry about sexual concerns anymore once they are past the child-bearing years.

In reality, many older couples find greater satisfaction in their sex life than they did when they were younger. They have fewer distractions, more time and privacy, no worries about getting pregnant, and greater intimacy with a lifelong partner (NIA, 2013). Results from the National Social Life Health, and Aging Project indicated that 72% of men and 45.5% of women aged 52 to 72 reported being sexually active (Karraker et al., 2011). Additionally, the National Survey of Sexual Health data indicated that 20%-30% of individuals remain sexually active well into their 80s (Schick et al., 2010). However, some issues occur in older adults that can adversely affect their enjoyment of healthy sexual relationships.

Causes of Sexual Problems

According to the National Institute on Aging (2013), chronic illnesses including arthritis (joint pain), diabetes (erectile dysfunction), heart disease (difficulty achieving orgasm for both sexes), stroke (paralysis), and dementia (inappropriate sexual behavior) can all adversely affect sexual functioning. Hormonal changes, physical disabilities, surgeries, and medicines can also affect a senior’s ability to participate in and enjoy sex. How one feels about sex can also affect performance. For example, a woman who is unhappy about her appearance as she ages may think her partner will no longer find her attractive. A focus on youthful physical beauty for women may get in the way of her enjoyment of sex. Likewise, most men have a problem with erectile dysfunction (ED) once in a while, and some may fear that ED will become a more common problem as they age. If there is a decline in sexual activity for a heterosexual couple, it is typically due to a decline in the male’s physical health (Erber & Szuchman, 2015).

Overall, the best way to experience a healthy sex life in later life is to keep sexually active while aging. However, the lack of an available partner can affect heterosexual women’s participation in a sexual relationship. Beginning at age 40 there are more women than men in the population, and the ratio becomes 2 to 1 at age 85 (Karraker et al., 2011). Because older men tend to pair with younger women when they become widowed or divorced, this also decreases the pool of available men for older women (Erber & Szuchman, 2015). In fact, a change in marital status does not result in a decline in the sexual behavior of men aged 57 to 85 years old, but it does result in a decline for similar-aged women (Karraker et al., 2011).

Societal Views on Sexuality

Society’s views on sexuality are influenced by everything from religion to philosophy, and they have changed throughout history and are continuously evolving. Historically, religion has been the greatest influence on sexual behavior in the United States; however, in more recent years, peers and the media have emerged as two of the strongest influences, particularly among American teens (Potard et al., 2008). Mass media in the form of television, magazines, movies, and music continues to shape what is deemed appropriate or normal sexuality, targeting everything from body image to products meant to enhance sex appeal. Media serves to perpetuate a number of social scripts about sexual relationships and the sexual roles of men and women, many of which have been shown to have both empowering and problematic effects on people’s (especially women’s) developing sexual identities and sexual attitudes.

Cultural Differences

In the West, premarital sex is normative by the late teens, more than a decade before most people enter marriage. In the United States, Canada, and northern and eastern Europe, cohabitation is also normative; most people have at least one cohabiting partnership before marriage. In southern Europe, cohabiting is still taboo, but premarital sex is tolerated in emerging adulthood. In contrast, both premarital sex and cohabitation remain rare and forbidden throughout Asia. Even dating is discouraged until the late twenties when it would be a prelude to a serious relationship leading to marriage. In cross-cultural comparisons, about three-fourths of emerging adults in the United States and Europe report having had premarital sexual relations by age 20, versus less than one-fifth in Japan and South Korea (Hatfield & Rapson, 2006).

14.5 Sexual Orientation

A person’s sexual orientation is their emotional and sexual attraction to a particular gender. It is a personal quality that inclines people to feel romantic or sexual attraction (or a combination of these) to persons of a given sex or gender. According to the American Psychological Association (APA) (2016), sexual orientation also refers to a person’s sense of identity-based on those attractions, related behaviors, and membership in a community of others who share those attractions. Sexual orientation is independent of gender; for example, a transgender person may identify as heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual, pansexual, polysexual, asexual, or any other kind of sexuality, just like a cisgender person.

Sexual Orientation on a Continuum

Sexuality researcher Alfred Kinsey was among the first to conceptualize sexuality as a continuum rather than a strict dichotomy of gay or straight. To classify this continuum of heterosexuality and homosexuality, Kinsey et al. (1948) created a seven-point rating scale that ranged from exclusively heterosexual to exclusively homosexual. Research done over several decades has supported this idea that sexual orientation ranges along a continuum, from exclusive attraction to the opposite sex/gender to exclusive attraction to the same sex/gender (Carroll, 2016).

However, sexual orientation now can be defined in many ways. Heterosexuality, which is often referred to as being straight, is an attraction to individuals of the opposite sex/gender, while homosexuality, being gay or lesbian, is an attraction to individuals of one’s own sex/gender. Bisexuality was a term traditionally used to refer to attraction to individuals of either male or female sex, but it has recently been used in non-binary models of sex and gender (i.e., models that do not assume there are only two sexes or two genders) to refer to attraction to any sex or gender. Alternative terms such as pansexuality and polysexuality have also been developed, referring to attraction to all sexes/genders and attraction to multiple sexes/genders, respectively (Carroll, 2016).

Asexuality refers to having no sexual attraction to any sex/gender. According to Bogaert (2015) about one percent of the population is asexual. Being asexual is not due to any physical problems, and the lack of interest in sex does not cause the individual any distress. Asexuality is being researched as a distinct sexual orientation.

Development of Sexual Orientation

According to current scientific understanding, individuals are usually aware of their sexual orientation between middle childhood and early adolescence. However, this is not always the case, and some do not become aware of their sexual orientation until much later in life. It is not necessary to participate in sexual activity to be aware of these emotional, romantic, and physical attractions; people can be celibate and still recognize their sexual orientation. Some researchers argue that sexual orientation is not static and inborn but is instead fluid and changeable throughout the lifespan.

There is no scientific consensus regarding the exact reasons why an individual holds a particular sexual orientation. Research has examined possible biological, developmental, social, and cultural influences on sexual orientation, but there has been no evidence that links sexual orientation to only one factor (APA, 2016). However, biological explanations, which include genetics, birth order, and hormones will be explored further as many scientists support biological processes occurring during the embryonic and and early postnatal life as playing the main role in sexual orientation (Balthazart, 2018).

Genetics

Using both twin and familial studies, heredity provides one biological explanation for same-sex orientation. Bailey and Pillard (1991) studied pairs of male twins and found that the concordance rate for identical twins was 52%, while the rate for fraternal twins was only 22%. Bailey et al. (1993) studied female twins and found a similar difference with a concordance rate of 48% for identical twins and 16% for fraternal twins. Schwartz et al. (2010) found that gay men had more gay male relatives than straight men, and sisters of gay men were more likely to be lesbians than sisters of straight men.

Fraternal Birth Order

The fraternal birth order effect indicates that the probability of a boy identifying as gay increases for each older brother born to the same mother (Balthazart, 2018; Blanchard, 2001). According to Bogaret et al. “the increased incidence of homosexuality in males with older brothers results from a progressive immunization of the mother against a male-specific cell-adhesion protein that plays a key role in cell-cell interactions, specifically in the process of synapse formation,” (as cited in Balthazart, 2018, p. 234). A meta-analysis indicated that the fraternal birth order effect explains the sexual orientation of between 15% and 29% of gay men.

Hormones

Excess or deficient exposure to hormones during prenatal development has also been theorized as an explanation for sexual orientation. One-third of females exposed to abnormal amounts of prenatal androgens, a condition called congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), identify as bisexual or lesbian (Cohen-Bendahan et al., 2005). In contrast, too little exposure to prenatal androgens may affect male sexual orientation by not masculinizing the male brain (Carlson, 2011).

Sexual Orientation Discrimination

The United States is heteronormative, meaning that society supports heterosexuality as the norm. Consider, for example, that homosexuals are often asked, “When did you know you were gay?” but heterosexuals are rarely asked, “When did you know you were straight?” (Ryle, 2011). Living in a culture that privileges heterosexuality has a significant impact on how non-heterosexual people can develop and express their sexuality.

Open identification of one’s sexual orientation may be hindered by homophobia, which encompasses a range of negative attitudes and feelings toward homosexuality or people who are identified or perceived as being lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and asexual (LGBTA+). It can be expressed as antipathy, contempt, prejudice, aversion, or hatred; it may be based on irrational fear and is sometimes related to religious beliefs (Carroll, 2016). Homophobia is observable in critical and hostile behavior, such as discrimination and violence based on non-heterosexual sexual orientations. Recognized types of homophobia include institutionalized homophobia, such as religious and state-sponsored homophobia, and internalized homophobia in which people with same-sex attractions internalize, or believe, society’s negative views and/or hatred of themselves.

Sexual minorities regularly experience stigma, harassment, discrimination, and violence based on their sexual orientation (Carroll, 2016). Research has shown that gay, lesbian, and bisexual teenagers are at a higher risk of depression and suicide due to exclusion from social groups, rejection from peers and family, and negative media portrayals of homosexuals (Bauermeister et al., 2010). Discrimination can occur in the workplace, in housing, at schools, and in numerous public settings. Much of this discrimination is based on stereotypes and misinformation. Major policies to prevent discrimination based on sexual orientation have only come into effect in the United States in the last few years.

The majority of empirical and clinical research on LGBTQA+ populations is done with largely white, middle-class, well-educated samples. This demographic limits our understanding of more marginalized sub-populations that are also affected by racism, classism, and other forms of oppression. In the United States, non-Caucasian LGBT individuals may find themselves in a double minority, in which they are not fully accepted or understood by Caucasian LGBT communities and are also not accepted by their own ethnic group (Tye, 2006). Many people experience racism in the dominant LGBT community where racial stereotypes merge with gender stereotypes.

Gay and Lesbian Elders

Approximately 3 million older adults in the United States identify as lesbian or gay (Hillman & Hinrichsen, 2014). By 2025 that number is expected to rise to more than 7 million (National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, 2006). Despite the increase in numbers, older lesbian and gay adults are one of the least researched demographic groups, and the research there is portrays a population faced with discrimination. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2011), compared to heterosexuals, lesbian and gay adults experience both physical and mental health differences. More than 40% of lesbian and gay adults ages 50 and over suffer from at least one chronic illness or disability and compared to heterosexuals they are more likely to smoke and binge drink (Hillman & Hinrichsen, 2014). Additionally, gay older adults have an increased risk of prostate cancer (Blank, 2005) and infection from HIV and other sexually transmitted illnesses (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008). When compared to heterosexuals, lesbian and gay elders have less support from others as they are twice as likely to live alone and four times less likely to have adult children (Hillman & Hinrichsen, 2014).

Lesbian and gay older adults who belong to ethnic and cultural minorities, conservative religions, and rural communities may face additional stressors. Ageism, heterocentrism, sexism, and racism can combine cumulatively and impact the older adult beyond the negative impact of each individual form of discrimination (Hillman & Hinrichsen, 2014). David and Knight (2008) found that older gay black men reported higher rates of racism than younger gay black men and higher levels of perceived ageism than older gay white men.

LGBTQA+ Elder Care

Approximately 7 million LGBTQA+ people over age 50 will reside in the United States by 2030, and 4.7 million of them will need elder care. Decisions regarding elder care is often left for families, and because many LGBT people are estranged from their families, they are left in a vulnerable position when seeking living arrangements (Alleccia & Bailey, 2019). A history of discriminatory policies, such as housing restricted to married individuals involving one man and one woman, and stigma associated with LGBT people make them especially vulnerable to negative housing experiences when looking for elder care.

Although lesbian and gay older adults face many challenges, more than 80% indicate that they engage in some form of wellness or spiritual activity (Fredrickson-Goldsen et al., 2011). They also gather social support from friends and “family members by choice” rather than legal or biological relatives (Hillman & Hinrichsen, 2014). This broader social network provides extra support to gay and lesbian elders.

An important consideration when reviewing the development of gay and lesbian older adults is the cohort in which they grew up (Hillman & Hinrichsen, 2014). The oldest lesbian and gay adults came of age in the 1950s when there were no laws to protect them from victimization. The baby boomers, who grew up in the 1960s and 1970s, began to see states repeal laws that criminalized homosexual behavior. Future lesbian and gay elders will have different experiences due to the legal right for same-sex marriage and greater societal acceptance. Consequently, just like all those in late adulthood, understanding that gay and lesbian elders are a heterogeneous population is important when understanding their overall development.

References

In progress…..