15 Interpersonal Relationships

Learning Objectives

- Describe the role of peers and dating relationships in adolescence

- Explain the development of friendships

- Demonstrate an understanding of the conept of love

- Describe adult lifestyles, including singlehood, cohabitation, and marriage

- Interpret the factors that influence parenting

- Explain the relationships middle-aged adults have with their children, parents, and other family members

- Explain the relationships those in late adulthood have with their children and other family members

- Describe singlehood, marriage, divorce, widowhood, remarriage at midlife and late adulthood

In chapter 15, we dive deep into the fascinating world of personal relationships specifically focusing on the complex dynamics of relationships that shape our lives. The human connection isn’t just a byproduct of adulthood; it’s a fundamental driving force, continually evolving and influencing our health and well-being. This chapter will begin by exploring the enduring significance of friendships, examining their changing roles and characteristics across the lifespan. Next, we will consider the unique developmental trajectory of singlehood, moving beyond simplistic definitions to understand its diverse the pathways that individuals forge outside of partnered relationships. From there, we will discuss the captivating realm of romantic relationships, explore various theories of attraction and unpack the complex and multifaceted construct of love itself.

Our exploration continues by investing marriage, where couples bring their personal relationships into the public realm by making a social and legal commitment to each other. However, marriage isn’t that straight forward, so we will analyze its various forms and how it impacts individuals and families. The profound shift to parenthood will be explored, alongside an in-depth look at different parenting styles and their influence on child development. We will also consider the often overlooked yet critically important influence of sibling relationships. Finally, recognizing that relationships can change and evolve, we will address the concept of divorce and the subsequent complexities and opportunities presented by remarriage. By the end of this chapter, you will have a comprehensive understanding of the rich and dynamic interpersonal relationships that envelop our lives.

15.1 Friendships

As toddlers, children may begin to show a preference for certain playmates (Ross & Lollis, 1989). However, peer interactions at this age often involve more parallel play rather than intentional social interactions (Pettit et al., 1996). By age four, many children use the word “friend” when referring to certain children and do so with a fair degree of stability (Hartup, 1983). However, among young children “friendship” is often based on proximity, such as they live next door, attending the same school, or it refers to whomever they just happen to be playing with at the time (Rubin, 1980).

Friendships take on new importance as judges of one’s worth, competence, and attractiveness in middle and late childhood. Friendships provide the opportunity to learn social skills, such as how to communicate with others and how to negotiate differences. Children get ideas from one another about how to perform certain tasks, how to gain popularity, what to wear or say, and how to act. This society of children marks a transition from a life focused on the family to a life concerned with peers. During middle and late childhood, peers increasingly play an important role. For example, peers play a key role in a child’s self-esteem at this age as any parent who has tried to console a rejected child will tell you. No matter how complementary and encouraging the parent may be, being rejected by friends can only be remedied by renewed acceptance. Children’s conceptualization of what makes someone a “friend” changes from a more egocentric understanding to one based on mutual trust and commitment. Both Bigelow (1977) and Selman (1980) believe that these changes are linked to advances in cognitive development.

Bigelow and La Gaipa (1975) outline three stages in children’s conceptualization of friendship.

- In stage one, reward-cost, friendship focuses on mutual activities. Children in early, middle, and late childhood all emphasize similar interests as the main characteristics of a good friend.

- In stage two, normative expectation focuses on conventional morality; that is, the emphasis is on a friend as someone who is kind and shares with you. Clark and Bittle (1992) found that fifth graders emphasized this in a friend more than third or eighth graders.

- In the final stage, empathy and understanding, friends are people who are loyal, committed to the relationship, and share intimate information. Clark and Bittle (1992) reported eighth graders emphasized this more in a friend. They also found that as early as fifth grade, girls were starting to include a sharing of secrets, and not betraying confidences as crucial to someone who is a friend.

Selman (1980) outlines five stages of friendship from early childhood through to adulthood:

- Momentary physical interaction, a friend is someone who you are playing with at this point in time. Selman notes that this is typical of children between the ages of three and six. These early friendships are based more on circumstances (e.g., a neighbor) than on genuine similarities.

- One-way assistance, a friend is someone who does nice things for you, such as saving you a seat on the school bus or sharing a toy. However, children in this stage, do not always think about what they are contributing to the relationships. Nonetheless, having a friend is important and children will sometimes put up with a not-so-nice friend, just to have a friend. Children as young as five and as old as nine may be in this stage.

- Fair-weather cooperation, children are very concerned with fairness and reciprocity, and thus, a friend is someone who returns a favor. In this stage, if a child does something nice for a friend there is an expectation that the friend will do something nice for them at the first available opportunity. When this fails to happen, a child may break off the friendship. Selman found that some children as young as seven and as old as twelve are in this stage.

- Intimate and mutual sharing, typically between the ages of eight and fifteen, a friend is someone who you can tell them things you would tell no one else. Children and teens in this stage no longer “keep score” and do things for a friend because they genuinely care for the person. If a friendship dissolves in the stage it is usually due to a violation of trust. However, children in this stage do expect their friends to share similar interests and viewpoints and may take it as a betrayal if a friend likes someone that they do not.

- Autonomous interdependence, a friend is someone who accepts you and that you accept as they are. In this stage children, teens, and adults accept and even appreciate differences between themselves and their friends. They are also not as possessive, so they are less likely to feel threatened if their friends have other relationships or interests. Children are typically twelve or older in this stage.

Peer Relationships

Sociometric assessment measures attraction between members of a group, such as a classroom of students. In sociometric research children are asked to mention the three children they like to play with the most, and those they do not like to play with. The number of times a child is nominated for each of the two categories (like, do not like) is tabulated. Popular children receive many votes in the “like” category, and very few in the “do not like” category. In contrast, rejected children receive more unfavorable votes and few favorable ones. Controversial children are mentioned frequently in each category, with several children liking them and several children placing them in the do not like category. Neglected children are rarely mentioned in either category, and the average child has a few positive votes with very few negative ones (Asher & Hymel, 1981).

Most children want to be liked and accepted by their friends. Some popular children are nice and have good social skills. These popular-prosocial children tend to do well in school and are cooperative and friendly. Popular-antisocial children may gain popularity by acting tough or spreading rumors about others (Cillessen & Mayeux, 2004). Rejected children are sometimes excluded because they are rejected-withdrawn. These children are shy and withdrawn and are easy targets for bullies because they are unlikely to retaliate when belittled (Boulton, 1999). Other rejected children are rejected-aggressive and are ostracized because they are aggressive, loud, and confrontational. The aggressive-rejected children may be acting out of a feeling of insecurity. Unfortunately, their fear of rejection only leads to behavior that brings further rejection from other children. Children who are not accepted are more likely to experience conflict, lack confidence, and have trouble adjusting (Klima & Repetti, 2008; Schwartz et al., 2014).

Friendships in Adulthood

Adults of all ages who reported having a confidante or close friend with whom they could share personal feelings and concerns believed these friends contributed to a sense of belonging, security, and overall well-being (Dunér & Nordstrom, 2007). Having a close friend is a factor in significantly lower odds of psychiatric morbidity including depression and anxiety (Harrison et al., 1999; Newton et al., 2008). The availability of a close friend has also been shown to lessen the adverse effects of stress on health (Kouzis & Eaton, 1998; Hawkley et al., 2008; Tower & Kasl, 1995). Additionally, poor social connectedness in adulthood is associated with a larger risk of premature mortality than cigarette smoking, obesity, and excessive alcohol use (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010).

Female friendships and social support networks at midlife contribute significantly to a woman’s feeling of life satisfaction and well-being (Borzumato-Gainey et al., 2009). Degges-White and Myers (2006) found that women who have supportive people in their life experience greater life satisfaction than do those who live a more solitary life. A friendship network or the presence of a confidant have both been identified for their importance to women’s mental health (Baruch & Brooks-Gunn, 1984). Unfortunately, with numerous caretaking responsibilities at home, it may be difficult for women to find time and energy to enhance friendships that provide an increased sense of life satisfaction (Borzumato-Gainey et al., 2009). Emslie et al. (2013) found that for men in midlife, the shared consumption of alcohol was important to creating and maintaining male friends. Drinking with friends was justified as a way for men to talk to each other, provide social support, relax, and improve mood. Although the social support provided when men drink together can be helpful, the role of alcohol in male friendships can lead to health-damaging behavior from excessive drinking

The importance of social relationships begins in early adulthood by laying down a foundation for strong social connectedness and facilitating comfort with intimacy (Erikson, 1959). To determine the impact of the quantity and quality of social relationships in young adulthood on middle adulthood, Carmichael et al. (2015) assessed individuals at age 50 on measures of social connection (types of relationships and friendship quality) and psychological outcomes (loneliness, depression, psychological well-being). Results indicated that the quantity of social interactions at age 20 and the quality, not quantity, of social interaction at age 30 predicted midlife social interactions. Those individuals who had high levels of social information seeking (quantity) at age 20 followed by less quantity in social relationships but greater emotional closeness (quality), resulted in positive psychosocial adjustment at midlife. Continuing to socialize widely in one’s 30s appeared to negatively affect the development of intimacy, and consequently resulted in worse psychological outcomes at age 50.

Internet Friendships

What influence does the Internet have on friendships? It is not surprising that people use the Internet with the goal of meeting and making new friends (Fehr, 2008; McKenna, 2008). Researchers have wondered if the issue of not being face-to-face reduces the authenticity of relationships, or if the Internet really allows people to develop deep, meaningful connections. Interestingly, research has demonstrated that virtual relationships are often as intimate as in-person relationships; in fact, Bargh and colleagues found that online relationships are sometimes more intimate (Bargh et al., 2002). This can be especially true for those individuals who are more socially anxious and lonely as such individuals are more likely to turn to the Internet to find new and meaningful relationships (McKenna et al., 2002). McKenna and colleagues suggest that for people who have a hard time meeting and maintaining relationships, due to shyness, anxiety, or lack of face-to-face social skills, the Internet provides a safe, nonthreatening place to develop and maintain relationships. Similarly, Benford (2008) found that for high-functioning autistic individuals, the Internet facilitated communication and relationship development with others, which would have been more difficult in face-to-face contexts, leading to the conclusion that Internet communication could be empowering for those who feel frustrated when communicating face to face.

Workplace Friendships

Friendships often take root in the workplace, due to the fact that people are spending as much, or more, time at work than they are with their family and friends (Kaufman & Hotchkiss, 2003). Often, it is through these relationships that people receive mentoring and obtain social support and resources, but they can also experience conflicts and the potential for misinterpretation when sexual attraction is an issue. Indeed, Elsesser and Peplau (2006) found that many workers reported that friendships grew out of collaborative work projects, and these friendships made their days more pleasant.

In addition to those benefits, Riordan and Griffeth (1995) found that people who worked in an environment where friendships could develop and be maintained were more likely to report higher levels of job satisfaction, job involvement, and organizational commitment, and they were less likely to leave that job. Similarly, a Gallup poll revealed that employees who had close friends at work were almost 50% more satisfied with their jobs than those who did not (Armour, 2007).

15.2 Singlehood

Being single is the most common lifestyle for people in their early 20s, and there has been an increase in the number of adults staying single. In 1960, only about 1 in 10 adults aged 25 or older had never been married, in 2012 that had risen to 1 in 5 (Wang & Parker, 2014). While just over half (53%) of unmarried adults say they would eventually like to get married, 32 percent are not sure, and 13 percent do not want to get married. It is projected that by the time current young adults reach their mid-40s and 50s, almost 25% of them may not have married. The U.S. is not the only country to see a rise in the number of single adults.

In addition, adults are marrying later in life, cohabitating, and raising children outside of marriage in greater numbers than in previous generations. Young adults also have other priorities, such as education, and establishing their careers. This may be reflected by changes in attitudes about the importance of marriage. In a recent Pew Research survey of Americans, respondents were asked to indicate which of the following statements came closer to their own views:

- “Society is better off if people make marriage and having children a priority”

- “Society is just as well off if people have priorities other than marriage and children”

Slightly more adults endorsed the second statement (50%) than those who chose the first (46%), with the remainder either selecting neither, both equally, or not responding (Wang & Parker, 2014). Young adults aged 18-29 were more likely to endorse this view than adults aged 30 to 49; 67% and 53 percent respectively. In contrast, those aged 50 or older were more likely to endorse the first statement (53%).

Singlehood in Middle Adulthood

According to a Pew Research study, 16 per 1,000 adults aged 45 to 54 and 7 per 1000 aged 55 and over have never married in the U.S. (Wang & Parker, 2014). However, some of them may be living with a partner. In addition, some singles in midlife may be single through divorce or widowhood. DePaulo (2014) has challenged the idea that singles, especially the always single, fair worse emotionally and in health when compared to those married. DePaulo suggests there is a bias in how studies examine the benefits of marriage. Most studies focus on comparisons between married and not married, which do not include a separate comparison between those always single, and those who are single because of divorce or widowhood. Her research has found that those who are married may be more satisfied with life than the divorced or widowed, but there is little difference between married and always single, especially when comparing those who are recently married with those who have been married for four or more years. It appears that once the initial blush of the honeymoon wears off, those who are wedded are no happier or healthier than those who remain single. This might also suggest that there may be problems with how the “married” category is also seen as one homogeneous group.

15.2 Romantic Relationships & Theories of Attraction

Adolescence is the developmental period during which romantic relationships typically first emerge. By the end of adolescence, most American teens have had at least one romantic relationship (Dolgin, 2011). However, culture does play a role as Asian Americans and Latinas are less likely to date than other ethnic groups (Connolly et al., 2004). Dating serves many purposes for teens, including having fun, companionship, status, socialization, sexual experimentation, intimacy, and partner selection for those in late adolescence (Dolgin, 2011).

There are several stages in the dating process beginning with engaging in mixed-sex group activities in early adolescence (Dolgin, 2011). The same-sex peer groups that were common during childhood expand into mixed-sex peer groups that are more characteristic of adolescence. Romantic relationships often form in the context of these mixed-sex peer groups (Connolly et al., 2000). Interacting in mixed-sex groups is easier for teens as they are among a supportive group of friends, can observe others interacting, and are kept safe from a too-early intimate relationship. By middle adolescence, teens are engaging in brief, casual dating or group dating with other couples (Dolgin, 2011). Then in late adolescence dating involves exclusive, intense relationships. These relationships tend to be long-lasting and continue for a year or longer, however, they may also interfere with friendships.

Although romantic relationships during adolescence are often short-lived rather than long-term committed partnerships, their importance should not be minimized. Adolescents spend a great deal of time focused on romantic relationships, and their positive and negative emotions are more tied to romantic relationships, or lack thereof than to friendships, family relationships, or school (Furman & Shaffer, 2003). Romantic relationships contribute to adolescents’ identity formation, changes in family and peer relationships, and emotional and behavioral adjustment.

Furthermore, romantic relationships are centrally connected to adolescents’ emerging sexuality. Parents, policymakers, and researchers have devoted a great deal of attention to adolescents’ sexuality, in large part because of concerns related to sexual intercourse, contraception, and preventing teen pregnancies. However, sexuality involves more than this narrow focus. For example, adolescence is often when individuals who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender come to perceive themselves as such (Russell et al., 2009). Thus, romantic relationships are a domain in which adolescents experiment with new behaviors and identities.

However, a negative dating relationship can adversely affect an adolescent’s development. Soller (2014) explored the link between relationship inauthenticity and mental health. Relationship inauthenticity refers to an incongruence between thoughts/feelings and actions within a relationship. Desires to gain partner approval and demands in the relationship may negatively affect an adolescent’s sense of authenticity. Soller (2014) found that relationship inauthenticity was positively correlated with poor mental health, including depression, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts, especially for females.

Theories of Attraction

Since most of us engage in an intimate relationship at some point, it is useful to know what psychologists have learned about the principles of liking and loving. Intimate relationships include connecting with and sharing personal information with friends and family, as well as partners or lovers. A major interest of psychologists is the study of interpersonal attraction, or what makes people like, and even love, each other.

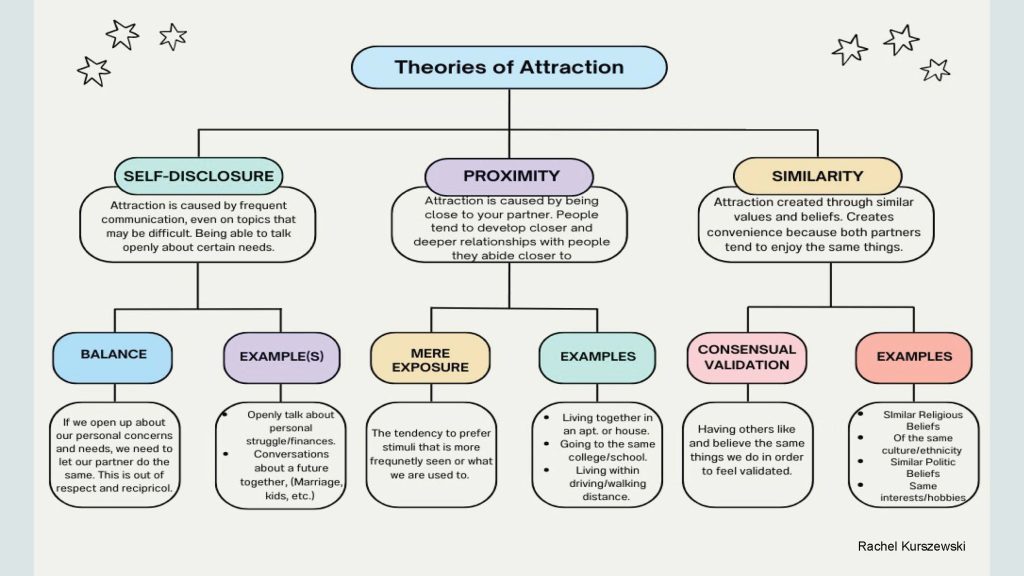

Similarity

One important factor in attraction is a perceived similarity in values and beliefs between the partners (Davis & Rusbult, 2001). Similarity is important for relationships because it is more convenient if both partners like the same activities and because similarity supports one’s values. When others’ beliefs, values, perceptions, and experiences are like our own, it makes us feel validated in our beliefs. Our understanding of reality is strengthened and affirmed when others share similar perspectives or agree with our interpretations. Not only is this essential for attraction but allows us to communicate more effectively with others. This concept of mutual understanding is referred to as consensual validation and is an important aspect of why we are attracted to others.

Self-Disclosure

Liking is also enhanced by self-disclosure, which is the tendency to communicate frequently, without fear of reprisal, and in an accepting and empathetic manner. Friends are friends because we can talk to them openly about our needs and goals and because they listen and respond to our needs (Reis & Aron, 2008). However, self-disclosure must be balanced. If we disclose about our concerns that are important to us, we expect our partner to do the same in return. If the self-disclosure is not reciprocal, the relationship may not last.

Proximity

Another important determinant of liking is proximity or the extent to which people are physically near us. Research has found that we are more likely to develop friendships with people who are nearby, for instance, those who live in the same dorm that we do, and even with people who just happen to sit nearer to us in our classes (Back, Schmukle, & Egloff, 2008).

Proximity has its effect on liking through the principle of mere exposure, which is the tendency to prefer stimuli (including, but not limited to people) that we have seen more frequently. The effect of mere exposure is powerful and occurs in a wide variety of situations. Infants tend to smile at a photograph of someone they have seen before more than they smile at a photograph of

Mere exposure may well have an evolutionary basis. We have an initial fear of the unknown, but as things become familiar, they seem more similar and safer and thus produce more positive effects and seem less threatening and dangerous (Harmon-Jones & Allen, 2001; Freitas et al., 2005). When the stimuli are people, there may be an added effect. Familiar people become more likely to be seen as part of the ingroup rather than the outgroup, and this may lead us to like them more. Zebrowitz and her colleagues (2007) found that we like people of our own race in part because they are perceived as similar to us.

Hooking Up

United States demographic changes have significantly affected romantic relationships among emerging and early adults. As previously described, the age for puberty has declined, while the times for one’s first marriage and first child have been pushed to older ages. This results in a “historically unprecedented time gap where young adults are physiologically able to reproduce, but not psychologically or socially ready to settle down and begin a family and child rearing,” (Garcia et al., 2012, p. 172). Consequently, according to Bogle (2007, 2008) traditional forms of dating have shifted to more casual hookups that involve uncommitted sexual encounters.

Even though most research on hooking up involves college students, 70% of sexually active 12-21-year-olds reported having had uncommitted sex during the past year (Grello et al., 2003). Additionally, Manning et al. (2006) found that 61% of sexually active seventh-, ninth-, and eleventh-graders reported being involved in a sexual encounter outside of a dating relationship.

Friends with Benefits

Hookups are different than those relationships that involve continued mutual exchange. These relationships are often referred to as Friends with Benefits (FWB) or “Booty Calls.” These relationships involve friends having casual sex without commitment. Hookups do not include a friendship relationship. Bisson and Levine (2009) found that 60% of 125 undergraduates reported a FWB relationship. The concern with FWB is that one partner may feel more romantically invested than the other (Garcia et al., 2012).

Hooking Up Gender Differences

When asked about their motivation for hooking up, both males and females indicated physical gratification, emotional gratification, and a desire to initiate a romantic relationship as reasons (Garcia & Reiber, 2008). Although males and females are more similar than different in their sexual behaviors, a consistent finding in the research is that males demonstrate a greater permissiveness to casual sex (Oliver & Hyde, 1993). In another study involving 16,288 individuals across 52 nations, males reported a greater desire for sexual partner variety than females, regardless of relationship status or sexual orientation (Schmitt et al., 2003). This difference can be attributed to gender role expectations for both males and females regarding sexual promiscuity. Additionally, the risks of sexual behavior are higher for females and include unplanned pregnancy, increased sexually transmitted diseases, and susceptibility to sexual violence (Garcia et al., 2012).

Although hooking-up relationships have become normalized for emerging adults, some research indicates that the majority of both sexes would prefer a more traditional romantic relationship (Garcia et al., 2012). Additionally, Owen and Fincham (2011) surveyed 500 college students with experience with hookups, and 65% of women and 45% of men reported that they hoped their hookup encounter would turn into a committed relationship. Further, 51% of women and 42% of men reported that they tried to discuss the possibility of starting a relationship with their hookup partner. Casual sex has also been reported to be the norm among gay men, but they too indicate a desire for romantic and companionate relationships (Clarke & Nichols, 1972).

Emotional Consequences of Hooking Up

Concerns regarding hooking-up behavior certainly are evident in the research literature. One significant finding is the high comorbidity of hooking up and substance use. Those engaging in non-monogamous sex are more likely to have used marijuana, cocaine, and alcohol, and the overall risks of sexual activity are drastically increased with the addition of alcohol and drugs (Garcia et al., 2012). Regret has also been expressed, and those who had the most regret after hooking up also had more symptoms of depression (Welsh et al., 2006). Hookups were also found to lower self-esteem, increase guilt, and foster feelings of using someone or feeling used. Females displayed more negative reactions than males, and this may be due to females identifying more emotional involvement in sexual encounters than males.

Hooking up can best be explained by a biological, psychological, and social perspective. Research indicates that emerging adults feel it is necessary to engage in hooking-up behavior as part of the sexual script depicted in the culture and media. Additionally, they desire sexual gratification. However, they also want a more committed romantic relationship and may feel regret about uncommitted sex.

Online Dating

The ways people are finding love have changed with the advent of the Internet. Nearly 50 million Americans have tried an online dating website or mobile app (Bryant & Sheldon, 2017). Online dating has also increased dramatically among those aged 18 to 24. Today, one in five emerging adults report using a mobile dating app, while in 2013 only 5% did, and 27% reported having used online dating, almost triple the rate in 2013 (Smith & Anderson, 2016).

In addition, Montenegro (2003) surveyed over 3,000 singles aged 40–69, and almost half of the participants reported their most important reason for dating was to have someone to talk to or do things with. Additionally, sexual fulfillment was also identified as an important goal for many. Alterovitz and Mendelsohn (2013) reviewed online personal ads for men and women over age 40 and found that romantic activities and sexual interests were mentioned at similar rates among the middle-aged and young-old age groups, but less for the old-old age group.

Due to changing social norms and shifting cohort demographics, it has become more common for single older adults to be involved in dating and romantic relationships (Alterovitz & Mendelsohn, 2011). An analysis of widows and widowers ages 65 and older found that 18 months after the death of a spouse, 37% of men and 15% of women were interested in dating (Carr, 2004a). Unfortunately, opportunities to develop close relationships often diminish in later life as social networks decrease because of retirement, relocation, and the death of friends and loved ones (de Vries, 1996). Consequently, older adults, much like those younger, are increasing their social networks using technologies, including e-mail, chat rooms, and online dating sites (Fox, 2004; Wright & Query, 2004; Papernow, 2018).

Online communication differs from face-to-face interaction in a number of ways. In face-to-face meetings, people have many cues upon which to base their first impressions. A person’s looks, voice, mannerisms, dress, scent, and surroundings all provide information in face-to-face meetings, but in computer-mediated meetings, written messages are the only cues provided. Fantasy is used to conjure up images of voice, physical appearance, mannerisms, and so forth. The anonymity of online involvement makes it easier to become intimate without fear of interdependence. When online, people tend to disclose more intimate details about themselves more quickly. A shy person can open up without worrying about whether or not the partner is frowning or looking away. Someone who has been abused may feel safer in virtual relationships. It is easier to tell one’s secrets because there is little fear of loss. One can find a virtual partner who is warm, accepting, and undemanding (Gwinnell, 1998), and exchanges can be focused more on emotional attraction than physical appearance.

Catfishing and other forms of scamming is an increasing concern for those who use dating and social media sites and apps. Catfishing refers to “a deceptive activity involving the creation of a fake online profile for deceptive purposes” (Smith et al., 2017, p. 33). Notre Dame University linebacker Manti Ta’o fell victim to a catfishing scam. The young woman “Kekua” who he had struck up an online relationship with was a hoax, and he was not the first person to have been scammed by this fictitious woman. A number of US states have passed legislation to address online impersonation, from stealing information and creating a fake account of a real person to the creation of a fictitious persona with the intent to defraud or harm others (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2017).

Cohabitation

In American society, as well as in a number of other cultures, cohabitation has become increasingly commonplace (Gurrentz, 2018). For many emerging adults, cohabitation has become more commonplace than marriage. While marriage is still a more common living arrangement for those 25-34, cohabitation has increased, while marriage has declined.

Gurrentz also found that cohabitation varies by socioeconomic status. Those who are married tend to have higher levels of education, and thus higher earnings, or earning potential. Copen, Daniels, and Mosher (2013) found that from 1995 to 2010 the median length of the cohabitation relationship had increased regardless of whether the relationship resulted in marriage, remained intact, or had since dissolved. In 1995 the median length of the cohabitation relationship was 13 months, whereas it was 22 months by 2010. Cohabitation for all racial/ethnic groups, except for Asian women increased between 1995 and 2010. 40% of the cohabitations transitioned into marriage within three years, 32% were still cohabitating, and 27% of cohabiting relationships had dissolved within three years.

Three explanations have been given for the rise of cohabitation in Western cultures.

- The first notes that the increase in individualism and secularism, and the resulting decline in religious observance, has led to greater acceptance and adoption of cohabitation (Lesthaeghe & Surkyn, 1988). Moreover, the more people view cohabitating couples, the more normal this relationship becomes, and the more couples will then cohabitate. Thus, cohabitation is both a cause and an effect of greater cohabitation.

- A second explanation focuses on the economic changes. The growth of industry and the modernization of many cultures has improved women’s social status, leading to greater gender equality and sexual freedom, with marriage no longer being the only long-term relationship option (Bumpass, 1990).

- A final explanation suggests that the change in employment requirements, with many jobs now requiring more advanced education, has led to a competition between marriage and pursuing post-secondary education (Yu & Xie, 2015). This might account for the increase in the age of first marriage in many nations. Taken together, the greater acceptance of premarital sex, and the economic and educational changes would lead to a transition in relationships. Overall, cohabitation may become a step in the courtship process or may, for some, replace marriage altogether.

Similar increases in cohabitation have also occurred in other industrialized countries. For example, rates are high in Great Britain, Australia, Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. More children in Sweden are born to cohabiting couples than to married couples. The lowest rates of cohabitation in industrialized countries are in Ireland, Italy, and Japan (Benokraitis, 2005).

Cohabitation in Non-Western Cultures; The Philippines and China

Similar to other nations, young people in the Philippines are more likely to delay marriage, cohabitate, and engage in premarital sex as compared to previous generations (Williams et al., 2007). Despite these changes, many young people are still not in favor of these practices. Moreover, there is still a persistence of traditional gender norms as there are stark differences in the acceptance of sexual behavior out of wedlock for men and women in Philippine society. Young men are given greater freedom. In China, young adults are cohabitating in higher numbers than in the past (Yu & Xie, 2015). Unlike many Western cultures, in China adults with higher, rather than lower, levels of education are more likely to cohabitate. Yu and Xie suggest this may be due to seeing cohabitation as being a more “innovative” behavior and that those who are more highly educated may have had more exposure to Western culture.

Living Apart Together

In addition to cohabiting, there has been an increase in living apart together (LAT), which is “a monogamous intimate partnership between unmarried individuals who live in separate homes but identify themselves as a committed couple” (Benson & Coleman, 2016, p. 797).

This trend has been found in several nations and is motivated by:

- A strong desire to be independent in day-to-day decisions

- Maintaining their own home

- Keeping boundaries around established relationships

- Maintaining financial stability

Besides the desire to be autonomous, there is also a need for companionship, sexual intimacy, and emotional support. According to Bensen and Coleman, there are differences in LAT among older and younger adults. Those who are younger often enter into LAT out of circumstances, such as the job market, and they frequently view this arrangement as a transitional stage. In contrast, 80% older adults reported that they did not wish to cohabitate or marry. For some it was a conscious choice to live more independently. For instance, older women desired the LAT lifestyle as a way of avoiding the traditional gender roles that are often inherent in relationships where the couple lives together. However, some older adults become LATs because they fear social disapproval from others if they were to live together.

15.3 Love

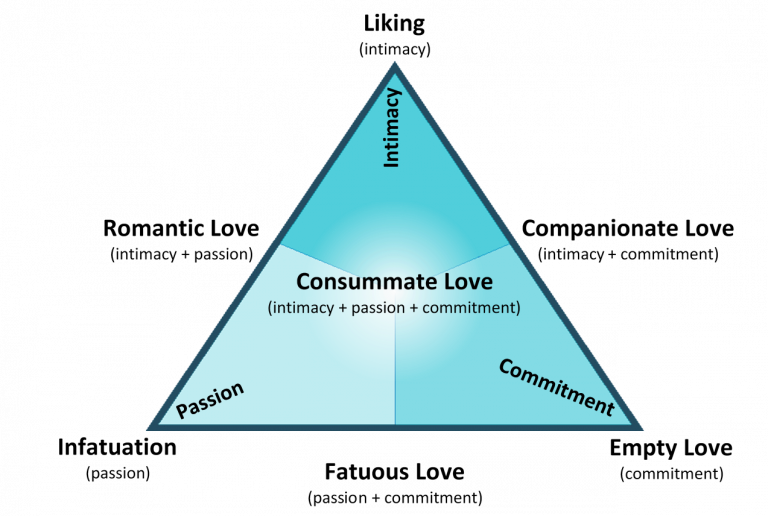

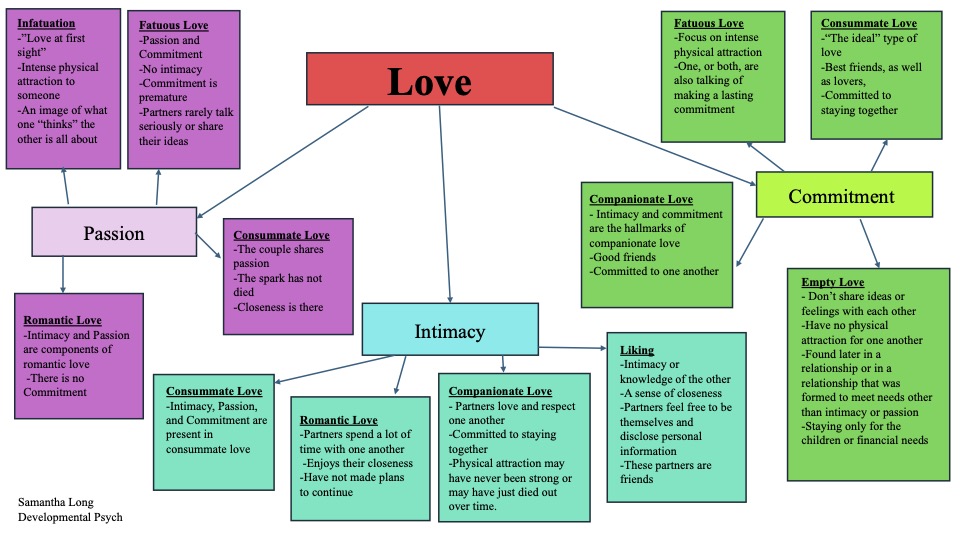

Sternberg (1988) suggests that there are three main components of love: Passion, intimacy, and commitment. Love relationships vary depending on the presence or absence of each of these components. Passion refers to the intense, physical attraction partners feel toward one another. Intimacy involves the ability the share feelings, psychological closeness, and personal thoughts with the other. Commitment is the conscious decision to stay together. Passion can be found in the early stages of a relationship, but intimacy takes time to develop because it is based on the knowledge of the partner. Once intimacy has been established, partners may resolve to stay in the relationship. Although many would agree that all three components are important to a relationship, many love relationships do not consist of all three. Thus, let’s explore the other possibilities.

Liking – In this relationship, intimacy or knowledge of the other and a sense of closeness is present. Passion and commitment, however, are not. Partners feel free to be themselves and disclose personal information. They may feel that the other person knows them well and can be honest with them and let them know if they think the person is wrong. These partners are friends. However, being told that your partner “thinks of you as a friend” can be a devastating blow if you are attracted to them and seeking a romantic involvement.

Infatuation – Perhaps, this is Sternberg’s version of “love at first sight”. Infatuation consists of an immediate, intense physical attraction to someone. A person who is infatuated finds it hard to think of anything but the other person. Brief encounters are played over and over in one’s head; it may be difficult to eat and there may be a rather constant state of arousal. Infatuation is rather short-lived, however, lasting perhaps only a matter of months or as long as a year or so. It tends to be based on physical attraction and an image of what one “thinks” the other is all about.

Fatuous Love – However, some people who have a strong physical attraction push for commitment early in the relationship. Passion and commitment are aspects of fatuous love. There is no intimacy and the commitment is premature. Partners rarely talk seriously or share their ideas. They focus on their intense physical attraction and yet one, or both, is also talking of making a lasting commitment. Sometimes this is out of a sense of insecurity and a desire to make sure the partner is locked into the relationship.

Empty Love – This type of love may be found later in a relationship or in a relationship that was formed to meet needs other than intimacy or passion, including financial needs, childrearing assistance, or attaining/maintaining status. Here the partners are committed to staying in the relationship for the children, because of a religious conviction, or because there are no alternatives. However, they do not share ideas or feelings with each other and have no physical attraction for one another.

Romantic Love – Intimacy and passion are components of romantic love, but there is no commitment. The partners spend much time with one another and enjoy their closeness but have not made plans to continue. This may be true because they are not able to make such commitments or because they are looking for passion and closeness and are afraid it will die out if they commit to one another and start to focus on other kinds of obligations.

Companionate Love – Intimacy and commitment are the hallmarks of companionate love. Partners love and respect one another, and they are committed to staying together. However, their physical attraction may have never been strong or may have just died out over time. Nevertheless, partners are good friends and committed to one another.

Consummate Love – Intimacy, passion, and commitment are present in consummate love. This is often perceived by Western cultures as “the ideal” type of love. The couple shares passion: the spark has not died, and the closeness is there. They feel like best friends, as well as lovers, and they are committed to staying together.

15.4 Marriage

Worldwide

Cohen (2013) reviewed data assessing most of the world’s countries and found that marriage has declined universally during the last several decades. This decline has occurred in both poor and rich countries, however, the countries with the biggest drops in marriage were mostly rich: France, Italy, Germany, Japan and the U.S. Cohen states that the decline is not only due to individuals delaying marriage, but also because of high rates of non-marital cohabitation. Delayed or reduced marriage is associated with higher income and lower fertility rates that are reflected worldwide.

United States

In 1960, 72% of adults aged 18 or older were married, in 2010 this had dropped to barely half (Wang & Taylor, 2011). At the same time, the age of first marriage has been increasing for both men and women. In 1960, the average age for first marriage was 20 for women and 23 for men. By 2010 this had increased to 26.5 for women and nearly 29 for men (see Figure 7.30). Many of the explanations for increases in singlehood and cohabitation previously given can also account for the drop and delay in marriage.

Same-Sex Marriage

In June 26, 2015, the United States Supreme Court ruled that the Constitution guarantees same-sex marriage. The decision indicated that limiting marriage to only heterosexual couples violated the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection under the law. This ruling occurred 11 years after same-sex marriage was first made legal in Massachusetts, and at the time of the high court decision, 36 states and the District of Columbia had legalized same-sex marriage. Worldwide, 30 countries currently have national laws allowing gays and lesbians to marry (Pew Research Center, 2023). As can be seen in the table below these countries are located mostly in Europe and the Americas.

Cultural Influences on Marriage

Many cultures have both explicit and unstated rules that specify who is an appropriate mate. Consequently, mate selection is not completely left to the individual. Rules of endogamy indicate the groups we should marry within and those we should not marry in (Witt, 2009). For example, many cultures specify that people marry within their own race, social class, age group, or religion. Endogamy reinforces the cohesiveness of the group. Additionally, these rules encourage homogamy or marriage between people who share social characteristics. The majority of marriages in the U. S. are homogamous with respect to race, social class, age and to a lesser extent, religion. Homogamy is also seen in couples with similar personalities and interests.

Arranged Marriages and Elopement

Historically, marriage was not a personal choice, but one made by one’s family. Arranged marriages often ensured proper transference of a family’s wealth and the support of ethnic and religious customs. Such marriages were marriages of families rather than of individuals. In Western Europe, starting in the 18th century the notion of personal choice in a marital partner slowly became the norm. Arranged marriages were seen as “traditional” and marriages based on love were “modern”. Many of these early “love” marriages were obtained by eloping (Thornton, 2005).

Around the world, more and more young couples are choosing their partners, even in nations where arranged marriages are still the norm, such as India and Pakistan. Desai and Andrist (2010) found that only 5% of the women they surveyed, aged 25-49, had a primary role in choosing their partner. Only 22% knew their partner for more than one month before they were married. However, the younger cohort of women was more likely to have been consulted by their families before their partner was chosen than the older cohort, suggesting that family views are changing about personal choice. Allendorf (2013) reports that this 5% figure may also underestimate young people’s choices, as only women were surveyed. Many families in India are increasingly allowing sons veto power over the parents’ choice of their future spouse, and some families give daughters the same say.

Marital Arrangements in India

As the number of arranged marriages in India is declining, elopement is increasing. Allendorf’s (2013) study of a rural village in India, describes the elopement process. In many cases, the female leaves her family home and goes to the male’s home, where she stays with him and his parents. After a few days, a member of his family will inform her family of her whereabouts and gain consent for the marriage. In other cases, where the couple anticipates some degree of opposition to the union, the couple may run away without the knowledge of either family, often going to a relative of the male.

After a few days, the couple comes back to the home of his parents, where at that point consent is sought from both families. Although, in some cases, families may sever all ties with their child or encourage him or her to abandon the relationship, typically, they agree to the union as the couple has spent time together overnight. Once consent has been given, the couple lives with his family and is considered married. A more formal ceremony takes place a few weeks or months later.

Arranged marriages are less common in the more urban regions of India than they are outside of the cities. In rural regions, often the family farm is the young person’s only means of employment. Thus, going against family choices may carry bigger consequences. Young people who live in urban centers have more employment options. As a result, they are often less economically dependent on their families and may feel freer to make their own choices. Thornton (2005) suggests these changes are also being driven by mass media, international travel, and the general Westernization of ideas. Besides India, China, Nepal, and several nations in Southeast Asia have seen a decline in the number of arranged marriages, and an increase in elopement or couples choosing their partners with their families’ blessings (Allendorf, 2013).

Predictors of Marital Harmony

Advice on how to improve one’s marriage is centuries old. One of today’s experts on marital communication is John Gottman. Gottman (1999) differs from many marriage counselors in his belief that having a good marriage does not depend on compatibility. Rather, the way that partners communicate to one another is crucial. At the University of Washington in Seattle, Gottman has measured the physiological responses of thousands of couples as they discuss issues of disagreement. Fidgeting in one’s chair, leaning closer to or further away from the partner while speaking, and increases in respiration and heart rate are all recorded and analyzed along with videotaped recordings of the partners’ exchanges. Gottman believes he can accurately predict whether or not a couple will stay together by analyzing their communication. In marriages destined to fail, partners engage in the “marriage killers”: Contempt, criticism, defensiveness, and stonewalling. Each of these undermines the politeness and respect that healthy marriages require. Stonewalling, or shutting someone out, is the strongest sign that a relationship is destined to fail.

Gottman, Carrere, Buehlman, Coan, and Ruckstuhl (2000) researched the perceptions newlyweds had about their partner and marriage. The oral history interview used in the study, which looks at eight variables in marriage including fondness/affection, we-ness, expansiveness/ expressiveness, negativity, disappointment, and three aspects of conflict resolution (chaos, volatility, glorifying the struggle), was able to predict the stability of the marriage with 87% accuracy at the four to six year-point and 81% accuracy at the seven to nine year-point. Gottman (1999) developed workshops for couples to strengthen their marriages based on the results of the oral history interview. Interventions include increasing the positive regard for each other, strengthening their friendship, and improving communication and conflict resolution patterns.

Accumulated Positive Deposits

When there is a positive balance of relationship deposits this can help the overall relationship in times of conflict. For instance, some research indicates that a husband’s level of enthusiasm in everyday marital interactions was related to a wife’s affection during conflict (Driver & Gottman, 2004), showing that being pleasant and making deposits can change the nature of conflict. Also, Gottman and Levenson (1992) found that couples rated as having more pleasant interactions, compared with couples with less pleasant interactions, reported marital problems as less severe, higher marital satisfaction, better physical health, and less risk for divorce. Finally, Janicki et al. (2006) showed that the intensity of conflict with a spouse predicted marital satisfaction unless there was a record of positive partner interactions, in which case the conflict did not matter as much. Again, it seems as though having a positive balance through prior positive deposits helps to keep relationships strong even amid conflict.

Marriage in Middle & Late Adulthood

As you read, there have been many changes in the marriage rate as more people are cohabitating, more are deciding to stay single, and more are getting married at a later age. 48% of adults aged 45-54 are married; either in their first marriage (22%) or have remarried (26%). This makes marriage the most common relationship status for middle-aged adults in the United States. Likewise, the most common living arrangement for those aged 65 and older in 2015 was marriage (AOA, 2017). Although this was more common for older men.

Marital satisfaction tends to increase for many couples in midlife as children are leaving home (Landsford et al., 2005). However, not all researchers agree. They suggest that those who are unhappy with their marriage are likely to have gotten divorced by now, making the quality of marriages later in life only look more satisfactory (Umberson et al., 2005).

Widowhood in Late Adulthood

Losing one’s spouse is one of the most difficult transitions in life. The Social Readjustment Rating Scale, commonly known as the Holmes-Rahe Stress Inventory, rates the death of a spouse as the most significant stressor (Holmes & Rahe, 1967). The loss of a spouse after many years of marriage may make an older adult feel adrift in life. They must remake their identity after years of seeing themselves as a husband or wife. Approximately, 1 in 3 women aged 65 and older are widowed, compared with about 1 in 10 men.

Loneliness is the biggest challenge for those who have lost their spouse (Kowalski & Bondmass, 2008). However, several factors can influence how well someone adjusts to this event. Older adults who are more extroverted (McCrae & Costa, 1988) and have higher self-efficacy, (Carr, 2004b) often fare better. Positive support from adult children is also associated with fewer symptoms of depression and better adjustment in the months following widowhood (Ha, 2010).

The context of the death is also an important factor in how people may react to the death of a spouse. The stress of caring for an ill spouse can result in a mixed blessing when the ill partner dies (Erber & Szchman, 2015). The death of a spouse who died after a lengthy illness may come as a relief for the surviving spouse, who may have had the pressure of providing care for someone who was increasingly less able to care for themselves. At the same time, this sense of relief may be intermingled with guilt for feeling relief at the passing of their spouse. The emotional issues of grief are complex and will be discussed in more detail in chapter 10.

Widowhood also poses health risks. The widowhood mortality effect refers to the higher risk of death after the death of a spouse (Sullivan & Fenelon, 2014). Subramanian, Elwert, and Christakis (2008) found that widowhood increases the risk of dying from almost all causes. However, research suggests that the predictability of the spouse’s death plays an important role in the relationship between widowhood and mortality. Elwert and Christakis (2008) found that the rate of mortality for windows and widowers was lower if they had time to prepare for the death of their spouse, such as in the case of a terminal illness like Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s. Another factor that influences the risk of mortality is gender. Men show a higher risk of mortality following the death of their spouse if they have higher health problems (Bennett et al., 2005). In addition, widowers have a higher risk of suicide than widows (Ruckenhauser et al., 2007).

15.5 Parenthood

Parenthood is undergoing changes in the United States and elsewhere in the world. Children are less likely to be living with both parents and women in the United States have fewer children than they did previously. The average fertility rate of women in the United States was about seven children in the early 1900s and has remained relatively stable at 2.1 since the 1970s (Hamilton et al., 2011; Martinez et al., 2012). Not only are parents having fewer children, but the context of parenthood has also changed. Parenting outside of marriage has increased dramatically among most socioeconomic, racial, and ethnic groups, although college-educated women are substantially more likely to be married at the birth of a child than mothers with less education (Dye, 2010).

People are having children at older ages, too. This is not surprising given that many of the age markers for adulthood have been delayed, including marriage, completing education, establishing oneself at work, and gaining financial independence. In 2014 the average age for American first-time mothers was 26.3 years (CDC, 2015a). The birth rate for women in their early 20s has declined in recent years, while the birth rate for women in their late 30s has risen. In 2011, 40% of births were to women ages 30 and older. For Canadian women, birth rates are even higher for women in their late 30s than in their early 20s. In 2011, 52% of births were to women ages 30 and older, and the average first-time Canadian mother was 28.5 years old (Cohn, 2013). Improved birth control methods have also enabled women to postpone motherhood. Even though young people are more often delaying childbearing, most 18- to 29-year-olds want to have children and say that being a good parent is one of the most important things in life (Wang & Taylor, 2011).

Life as a Family

One of the ways to assess the quality of family life is to consider the tasks of families. Berger (2014) lists five family functions:

- Providing food, clothing and shelter

- Encouraging learning

- Developing self-esteem

- Nurturing friendships with peers

- Providing harmony and stability

Notice that in addition to providing food, shelter, and clothing, families are responsible for helping the child learn, relate to others, and have a confident sense of self. Hopefully, the family will provide a harmonious and stable environment for living. A good home environment is one in which the child’s physical, cognitive, emotional, and social needs are adequately met. Sometimes families emphasize physical needs but ignore cognitive or emotional needs. Other times, families pay close attention to physical needs and academic requirements but may fail to nurture the child’s friendships with peers or guide the child toward developing healthy relationships.

Parents might want to consider how it feels to live in the household as a child. The tasks of families listed above are functions that can be fulfilled in a variety of family types just intact, two-parent households.

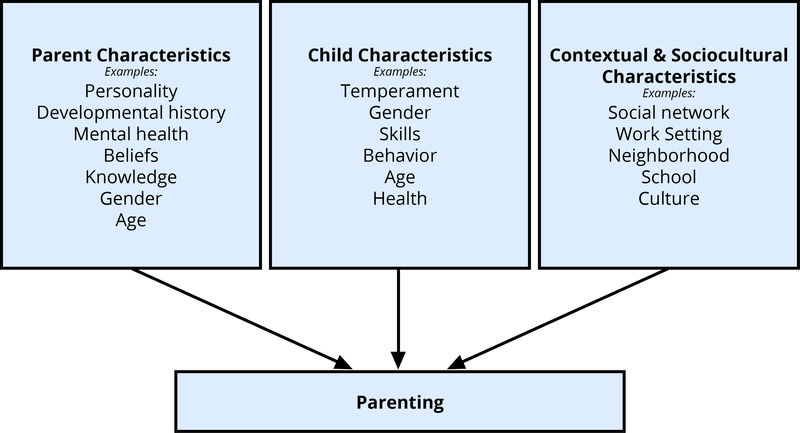

Influences on Parenting

Parenting is a complex process in which parents and children influence one another. There are many reasons that parents behave the way they do. The multiple influences on parenting are still being explored. Proposed influences on parenting include: Parent characteristics, child characteristics, and contextual can sociocultural characteristics. (Belsky, 1984; Demick, 1999).

Parent Characteristics

Parents bring unique traits and qualities to the parenting relationship that affect their decisions as parents. These characteristics include the age of the parent, gender, beliefs, personality, developmental history, knowledge about parenting and child development, and mental and physical health. Parents’ personalities affect parenting behaviors. Mothers and fathers who are more agreeable, conscientious, and outgoing are warmer and provide more structure to their children. Parents who are more agreeable, less anxious, and less negative also support their children’s autonomy more than parents who are anxious and less agreeable (Prinzie et al., 2009). Parents who have these personality traits appear to be better able to respond to their children positively and provide a more consistent, structured environment for their children. Parents’ developmental histories, or their experiences as children, also affect their parenting strategies. Parents may learn parenting practices from their parents. Fathers whose own parents provided monitoring, consistent and age-appropriate discipline, and warmth were more likely to provide this constructive parenting to their children (Kerr et al., 2009). Patterns of negative parenting and ineffective discipline also appear from one generation to the next. However, parents who are dissatisfied with their own parents’ approach may be more likely to change their parenting methods with their children.

Child Characteristics

As previously discussed, parenting is bidirectional. Not only do parents affect their children, but children also influence their parents. Child characteristics, such as gender, birth order, temperament, and health status, affect parenting behaviors and roles. For example, an infant with an easy temperament may enable parents to feel more effective, as they are easily able to soothe the child and elicit smiling and cooing. On the other hand, a cranky or fussy infant elicits fewer positive reactions from his or her parents and may result in parents feeling less effective in the parenting role (Eisenberg et al., 2008). Over time, parents of more difficult children may become more punitive and less patient with their children (Clark et al., 2000; Eisenberg et al., 1999; Kiff et al., 2011). Parents who have a fussy, difficult child are less satisfied with their marriages and have greater challenges in balancing work and family roles (Hyde et al., 2004). Thus, child temperament, as previously discussed, is one of the child characteristics that influence how parents behave with their children.

Another child characteristic is the gender of the child. Parents respond differently to boys and girls. Parents often assign different household chores to their sons and daughters. Girls are more often responsible for caring for younger siblings and household chores, whereas boys are more likely to be asked to perform chores outside the home, such as mowing the lawn (Grusec et al., 1996). Parents also talk differently with their sons and daughters, providing more scientific explanations to their sons and using more emotional words with their daughters (Crowley et al., 2001).

Contextual Factors and Sociocultural Characteristics

The parent–child relationship does not occur in isolation. Sociocultural characteristics, including economic hardship, religion, politics, neighborhoods, schools, and social support, also influence parenting. Parents who experience economic hardship are more easily frustrated, depressed, and sad, and these emotional characteristics affect their parenting skills (Conger & Conger, 2002). Culture also influences parenting behaviors in fundamental ways. Although promoting the development of skills necessary to function effectively in one’s community is a universal goal of parenting, the specific skills necessary vary widely from culture to culture. Thus, parents have different goals for their children that partially depend on their culture (Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2008).

Parents vary in how much they emphasize goals for independence and individual achievements, maintaining harmonious relationships, and being embedded in a strong network of social relationships. Other important contextual characteristics, such as the neighborhood, school, and social networks, also affect parenting, even though these settings do not always include both the child and the parent (Brofenbrenner, 1989). Culture is also a contributing contextual factor, as discussed previously in chapter four. For example, Latina mothers who perceived their neighborhood as more dangerous showed less warmth with their children, perhaps because of the greater stress associated with living in a threatening environment (Gonzales et al., 2011).

15.6 Parenting Styles

Relationships between parents and children continue to play a significant role in children’s development during early childhood. As children mature, parent-child relationships naturally change. Preschool and grade-school children are more capable, have their own preferences, and sometimes refuse or seek to compromise with parental expectations. This can lead to greater parent-child conflict, and how conflict is managed by parents further shapes the quality of parent-child relationships.

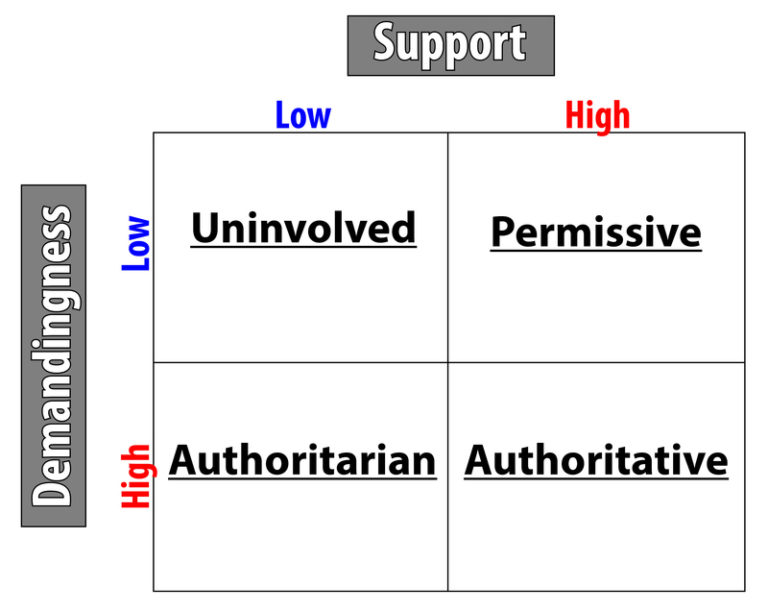

Baumrind (1971) identified a model of parenting that identifies a collection of attitudes and behaviors that parents communicate to their children through their interactions. Furthermore, Baumrind’s model (1971) focuses on the level of control/expectations that parents have regarding their children and how warm/responsive they are to their children. Baumrind’s model resulted in the following four parenting styles:

1) An authoritative parenting style (democratic) is supportive and shows interest in their kids’ activities but is not overbearing and allows them to make constructive mistakes. This kind of parenting style, described as authoritative by Baumrind (2013), fosters an environment where children can develop greater competence and self-confidence. These parents set high, but reasonable, expectations for their children’s behavior, communicate effectively, and prioritize reasoning over coercion when addressing misbehavior. This warm and responsive approach, coupled with opportunities for appropriate negotiation, creates a more democratic dynamic within the family, ultimately contributing to children’s positive development.

The potential outcomes of the authoritative style:

- Children appear happy and content, more independent, and more active

- Children achieve higher academic success, develop good self-esteem, and interact with peers using competent social skills

- Children have better mental health, exhibit less violent tendencies, and are securely attached

2) An authoritarian parenting style (dictator) is the traditional model of parenting in which parents make the rules and children are expected to be obedient. Baumrind suggests that authoritarian parents tend to place maturity demands on their children that are unreasonably high and tend to be aloof and distant. Consequently, children reared in this way may fear rather than respect their parents and, because their parents do not allow discussion, may take out their frustrations on safer targets, perhaps as bullies toward peers.

The potential outcomes of the authoritarian style:

- Children have an unhappy disposition, are less independent, and appear insecure

- Children possess low self-esteem, exhibit more behavioral problems, and perform worse academically

- Children have poorer social and coping skills, are more prone to issues with mental health, and are likely to have drug use problems

3) A permissive parenting style (indulgent) involves holding expectations of children that are below what could be reasonably expected from them. Children are allowed to make their own rules and determine their own activities. Parents are warm and communicative but provide little structure or limits for their children. Children fail to learn self-discipline and may feel somewhat insecure because they do not know the limits. Screen time and snacks are not monitored in this type of family, which can lead to a risk of obesity and typically four hours of television per day (Trautner, 2017).

The potential outcomes of the permissive parenting style:

- Children have difficulty following rules, difficulty with self-control, have more egocentric tendencies, and encounter more problems in relationships and social interactions

- Children can be impulsive, aggressive, and lack personal responsibility, mainly due to the huge lack of boundaries.

- Children can have symptoms of anxiety and depression.

- Children may have an overinflated self-esteem.

4) An uninvolved parent style (neglectful) occurs when the parents disengage from their children. They do not make demands on their children and are non-responsive. These children can suffer in school and their relationships with their peers (Gecas & Self, 1991).

The potential outcomes of the uninvolved parenting style:

- Children can be more impulsive and have difficulty with self-regulating their emotions

- Children may encounter more delinquency and addiction problems

- Children may have issues with mental health — e.g. suicidal behavior in adolescents

Keep in mind that most parents do not follow any model completely. Real people tend to fall somewhere in between these styles. Sometimes parenting styles change from one child to the next or in times when the parent has more or less time and energy for parenting. Parenting styles can also be affected by concerns the parent has in other areas of his or her life. For example, parenting styles tend to become more authoritarian when parents are tired and perhaps more authoritative when they are more energetic. Sometimes parents seem to change their parenting approach when others are around, maybe because they become more self-conscious as parents or are concerned with giving others the impression that they are a “tough” parent or an “easy-going” parent. Additionally, parenting styles may reflect the type of parenting someone saw modeled by their parents or other adults while growing up.

Additionally, the impact of culture and class cannot be ignored when examining parenting styles. The model of parenting described above assumes that the authoritative style is the best because this style is designed to help the parent raise a child who is independent, self-reliant, and responsible. These are qualities favored in “individualistic” cultures such as the United States, particularly by the middle class. However, in “collectivistic” cultures such as China or Korea, being obedient and compliant are favored behaviors. Authoritarian parenting has been used historically and reflects the cultural need for children to do as they are told. African American, Hispanic, and Asian parents tend to be more authoritarian than non-Hispanic whites.

In societies where family members’ cooperation is necessary for survival, rearing children who are independent and who strive to be on their own makes no sense. However, in an economy based on being mobile to find jobs and where one’s earnings are based on education, raising a child to be independent is very important.

In a classic study on social class and parenting styles, Kohn (1977) explains that parents tend to emphasize qualities that are needed for their survival when parenting their children. Working-class parents are rewarded for being obedient, reliable, and honest in their jobs. They are not paid to be independent or to question the management; rather, they move up and are considered good employees if they show up on time, do their work as they are told, and can be counted on by their employers. Consequently, these parents reward honesty and obedience in their children. Middle-class parents who work as professionals are rewarded for taking initiative, being self-directed, and being assertive in their jobs. They are required to get the job done without being told exactly what to do. They are asked to be innovative and to work independently. These parents encourage their children to have those qualities as well by rewarding independence and self-reliance. Parenting styles can reflect many elements of culture.

Since parenting styles are influenced by culture, researchers have identified some additional parenting approaches that do not apply to Baumrind’s styles, definitions, or outcomes. The table below is an overview of three additional approaches–overindulgent parenting, helicopter parenting, and traditional parenting (Lang, 2020).

| Style | Definition | Examples | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Helicopter | Occurs when caregivers are extremely overinvolved in their child’s life due to the belief that they can protect their child’s physical and/or emotional well-being. Caregivers using this approach appear overbearing & overprotective due to the close attention they pay to their child’s problems & successes. Parents “hover overhead” by constantly overseeing with excessive interest. Some contend that cell phones are “the world’s longest umbilical cord” which is contributing to this phenomenon. | • Solving problems for their children • Constantly supervising & correcting kids • Overly involving themselves in their children's academic performance or sports • Overly worried about their children's safety • Having strict rules for their children • Cleaning up after kids & doing their chores/work for them |

• Stifled developmental growth because of not experiencing or learning “necessary” life lessons • Potential for long-term mental health problems (anxiety & depression) • Rebellious behaviors in adolescence [4] • A lack of independence coupled with poor decision-making, motivational, & coping skills [5] |

| Overindulgent | Occurs when providing children with too much of what “looks good, too soon, too long.”[1] Often, it appears that parents implement these strategies to fulfill their own unmet needs or feelings of neglect from their own childhood. | • Giving children an overabundance of things or experiences that are not developmentally appropriate for the child • Family resources appear to meet the child’s needs but do not • Anything that actively harms or prevents a child from developing & achieving one’s full potential • Freedom with minimal boundaries & limits that are developmentally inappropriate for the child [2] |

• Extreme self-centeredness; narcissism • Excessive degrees of a sense of entitlement • Poor decision-making & coping skills • Stifled developmental growth because of not experiencing or learning “necessary” life lessons • Learned helplessness |

| Traditional | Parents expect their children to respect & obey authority & comply with their cultural beliefs/values without questions. Families who self-identify as Asian Americans & Latino Americans engage in high demandingness & expect respect & obedience from their children. However, these caregivers also value closeness & love that is different from the authoritarian parenting style. | • High in demandingness • Warm & responsive to the child’s needs, like the authoritative approach • Value closeness & love • They do not engage in democratic discussions [6] • Children are expected to defer to elders |

• Higher academic achievements • Lower behavioral & psychological problems when compared to their peers who are reared by caregivers using the authoritarian approach positive outcomes may be related to the closeness/love shown to children, which is different from the “cold” or “distant” characteristics consistent with the authoritarian style |

Lesbian and Gay Parenting

Research has consistently shown that the children of lesbian and gay parents are as successful as those of heterosexual parents, and consequently, efforts are being made to ensure that gay and lesbian couples are provided with the same legal rights as heterosexual couples when adopting children (American Civil Liberties Union, 2016).

Patterson (2013) reviewed more than 25 years of social science research on the development of children raised by lesbian and gay parents and found no evidence of detrimental effects. Research has demonstrated that children of lesbian and gay parents are as well-adjusted overall as those of heterosexual parents. Specifically, research comparing children based on parental sexual orientation has not shown any differences in the development of gender identity, gender role development, or sexual orientation. Additionally, there were no differences between the children of lesbian or gay parents and those of heterosexual parents in separation-individuation, behavior problems, self-concept, locus of control, moral judgment, school adjustment, intelligence, victimization, and substance use. Further, research has consistently found that children and adolescents of gay and lesbian parents report normal social relationships with family members, peers, and other adults. Patterson concluded that there is no evidence to support legal discrimination or policy bias against lesbian and gay parents.

Parents and Teens: Autonomy and Attachment

While most adolescents get along with their parents, they do spend less time with them (Smetana, 2011). This decrease in the time spent with families may reflect a teenager’s greater desire for independence or autonomy. It can be difficult for many parents to deal with this desire for autonomy. However, it is likely adaptive for teenagers to increasingly distance themselves and establish relationships outside of their families in preparation for adulthood. This means that both parents and teenagers need to strike a balance between autonomy, while still maintaining close and supportive familial relationships.

Children in middle and late childhood are increasingly granted greater freedom regarding moment-to-moment decision-making. This continues in adolescence, as teens are demanding greater control in decisions that affect their daily lives. This can increase conflict between parents and their teenagers. For many adolescents, this conflict centers on chores, homework, curfew, dating, and personal appearance. These are all things many teens believe they should Peers can serve both positive and negative functions during adolescence. Negative peer pressure can lead adolescents to make riskier decisions or engage in more problematic behavior than they would alone or in the presence of their family. For example, adolescents are much more likely to drink alcohol, use drugs, and commit crimes when they are with their friends than when they are alone or with their family. One of the most widely studied aspects of adolescent peer influence is known as deviant peer contagion (Dishion & Tipsord, 2011), which is the process by which peers reinforce problem behavior by laughing or showing other signs of approval that then increase the likelihood of future problem behavior. However, peers also serve as an important source of social support and companionship during adolescence, and adolescents with positive peer relationships are happier and better adjusted than those who are socially isolated or have conflictual peer relationships.

Crowds are an emerging level of peer relationships in adolescence. In contrast to friendships, which are reciprocal dyadic relationships, and cliques (reference groups), which refer to groups of individuals who interact frequently, crowds are characterized more by shared reputations or images than actual interactions (Brown & Larson, 2009). These crowds reflect different prototypic identities, such as jocks or brains, and are often linked with adolescents’ social status and peers’ perceptions of their values or behaviors.

Relationship with Adult Children in Late Adulthood