12 Morality Development

Learning Objectives

- Explain the role of conscience in moral development

- Compare and contrast the theory of mind in neurotypical individuals with its presentation in individuals with autism spectrum disorder

- Compare and contrast Kohlberg’s Stages of Moral Development with Gilligan’s positions on the Morality of Care

Moral development occurs as the result of cognitive, social, and psychological factors and is deeply influenced by one’s family, culture, and experiences. Our sense of morality is crucial for our ability to show empathy and develop human relationships. However, the development of morality has been historically studied from a cognitive perspective, even though research has shown that human decision-making about morality is not a “cold” process; that is, it involves intuition and feeling, in addition to cognitive processes. Given the historical emphasis of cognition in studying morality, this section will examine the development of morality from a cognitive perspective. We will begin by examining the cognitive and social foundations necessary for humans to develop a sense of morality, and then we will examine theories of how morality develops across the lifespan.

12.1 Foundations of Morality

Conscience

Social and personality development is built from social, biological, and representational influences. These influences result in important developmental outcomes that matter to children, parents, and society: a young adult’s capacity to engage in socially constructive actions (helping, caring, sharing with others), to curb hostile or aggressive impulses, to live according to meaningful moral values, to develop a healthy identity and sense of self, and to develop talents and achieve success in using them. These are some of the developmental outcomes that denote social and emotional competence.

These social and personality development achievements derive from the interaction of many social, biological, and representational influences. Consider, for example, the development of conscience, which is an early foundation for moral development.

Conscience consists of the cognitive, emotional, and social influences that cause young children to create and act consistently with internalized standards of right and wrong (Kochanska, 2002). It emerges from young children’s experiences with parents, particularly in the development of a mutually responsive relationship that motivates young children to respond constructively to the parents’ requests and expectations. Biologically based temperament is involved, as some children are temperamentally more capable of motivated self-regulation (a quality called effortful control) than others, while some children are more prone to the fear and anxiety that parental disapproval can evoke. The development of conscience is influenced by having a good fit between the child’s temperamental qualities and the ways parents communicate and reinforce behavioral expectations.

Conscience development also expands as young children begin to represent moral values and think of themselves as moral beings. By the end of the preschool years, for example, young children develop a “moral self” by which they think of themselves as people who want to do the right thing, who feel badly after misbehaving, and who feel uncomfortable when others misbehave. In the development of conscience, young children become more socially and emotionally competent, providing a foundation for later moral conduct (Thompson, 2012).

12.2 Theory of Mind

Theory of mind refers to the ability to think about other people’s thoughts. Theory of mind is the understanding that other people experience mental states (for instance, thoughts, beliefs, feelings, or desires) that are different from our own, and that their mental states are what guide their behavior. This skill, which emerges in early childhood, helps humans to infer, predict, and understand the reactions of others, thus playing a crucial role in social development and in promoting competent social interactions.

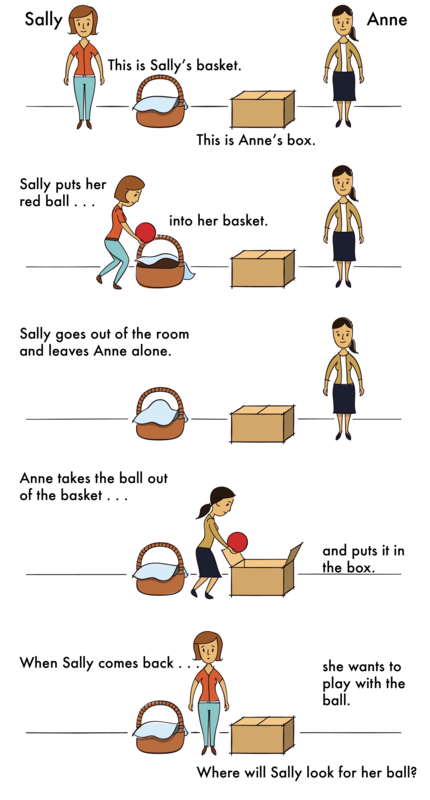

One common method for determining if a child has reached this mental milestone is called the false belief task. The research began with a clever experiment by Wimmer and Perner (1983), who tested whether children could pass a false-belief test. The child is shown a picture story of Sally, who puts her ball in a basket and leaves the room. While Sally is out of the room, Anne comes along and takes the ball from the basket and puts it inside a box. The child is then asked where Sally thinks the ball is located when she comes back to the room. Is she going to look first in the box or in the basket? The right answer is that she will look in the basket because that is where she put it and thinks it is; but we have to infer this false belief against our own better knowledge that the ball is in the box. This is very difficult for children before the age of four because of the cognitive effort it takes.

Three-year-olds have difficulty distinguishing between what they once thought was true and what they now know to be true. They feel confident that what they know now is what they have always known (Birch & Bloom, 2003). You could say that their perspectives are fused: whatever is actually true is what they and everyone else thinks. Even adults need to think through this task (Epley et al., 2004). To be successful at solving this type of task, the child must separate three things: (1) what is true; (2) what they themselves think (which can be false); and (3) what someone else thinks (which can be different from what they think as well as different from reality). Can you see why this task is so complex?

In Piagetian terms, children must give up a tendency toward egocentrism. The child must also understand that what guides people’s actions and responses is what they believe rather than what is true. In other words, people can mistakenly believe false things (called false beliefs) and will act based on this false knowledge. Consequently, before age four, children are rarely successful at solving such tasks (Wellman et al., 2001).

Researchers examining the development of the theory of mind have been concerned by the overemphasis on the mastery of false belief as the primary measure of whether a child has attained the theory of mind. Two-year-olds understand the diversity of desires, yet as noted earlier it is not until age four or five that children grasp false beliefs, and often not until middle childhood do they understand that people may hide how they really feel. In part, because children’s understanding is fused: in early childhood children do not differentiate genuine feelings from the expression of feelings. They have difficulty hiding how they really feel (e.g., saying thank you for a gift they do not really like). Wellman and his colleagues (Wellman, et al., 2006) suggest that the theory of mind is comprised of a number of components, each with its own developmental timeline.

Those in early childhood in the US, Australia, and Germany developed the theory of mind in the sequence outlined in the table above. Yet, Chinese and Iranian preschoolers acquire knowledge access before diverse beliefs (Shahaeian et al., 2011). Shahaeian and colleagues suggested that cultural differences in child-rearing may account for this reversal. Parents in collectivistic cultures, such as China and Iran, emphasize conformity to the family and cultural values, greater respect for elders, and the acquisition of knowledge and academic skills more than they do autonomy and social skills (Frank et al., 2010). This could reduce the degree of familial conflict of opinions expressed in the family. In contrast, individualistic cultures encourage children to think for themselves and assert their own opinions, and this could increase the risk of conflict in beliefs being expressed by family members. As a result, children in individualistic cultures would acquire insight into the question of diversity of belief earlier, while children in collectivistic cultures would acquire knowledge access earlier in the sequence. The role of conflict in aiding the development of theory of mind may account for the earlier age of onset of an understanding of false belief in children with siblings, especially older siblings (McAlister & Petersen, 2007; Perner et al., 1994).

This awareness of the existence of theory of mind is part of social intelligence, such as recognizing that others can think differently about situations. It helps us to be self-conscious or aware that others can think of us in different ways, and it helps us to be able to be understanding or be empathetic toward others. Moreover, this “mind reading” ability helps us to anticipate and predict people’s actions. The awareness of the mental states of others is important for communication and social skills.

Watch the video above to view the Sally-Anne test in action. You can access a copy of the video transcript here.

Impaired Theory of Mind in Individuals with Autism

People with autism or an autism spectrum disorder (ASD) typically show an impaired ability to recognize other people’s minds. Under the DSM-5, autism is characterized by persistent deficits in social communication and interaction across multiple contexts, as well as restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities. These deficits are present in early childhood, typically before age three, and lead to clinically significant functional impairment. Symptoms may include lack of social or emotional reciprocity, stereotyped and repetitive use of language or idiosyncratic language, and persistent preoccupation with unusual objects.

About half of parents of children with ASD notice their child’s unusual behaviors by age 18 months, and about four-fifths notice by age 24 months, but often a diagnosis comes later, and individual cases vary significantly. Typical early signs of autism include:

- No babbling by 12 months.

- No gesturing (pointing, waving, etc.) by 12 months.

- No single words by 16 months.

- No two-word (spontaneous, not just echolalic) phrases by 24 months.

- Loss of any language or social skills, at any age.

Children with ASD experience difficulties with explaining and predicting other people’s behavior, which leads to problems in social communication and interaction. Children who are diagnosed with an autistic spectrum disorder usually develop the theory of mind more slowly than other children and continue to have difficulties with it throughout their lives.

For testing whether someone lacks the theory of mind, the Sally-Anne test is performed. The child sees the following story: Sally and Anne are playing. Sally puts her ball into a basket and leaves the room. While Sally is gone, Anne moves the ball from the basket to the box. Now Sally returns. The question is: where will Sally look for her ball? The test is passed if the child correctly assumes that Sally will look in the basket. The test is failed if the child thinks that Sally will look in the box. Children younger than four and older children with autism will generally say that Sally will look in the box.

12.3 Kohlberg’s Stages of Moral Development

Kohlberg (1963) built on the work of Piaget and was interested in finding out how our moral reasoning changes as we get older. He wanted to find out how people decide what is right and what is wrong. Just as Piaget believed that children’s cognitive development follows specific age-graded stages, Kohlberg (1984) argued that we learn our moral values through active thinking and reasoning. To study moral development, Kohlberg posed moral dilemmas to children, teenagers, and adults, such as the following:

A man’s wife is dying of cancer and there is only one drug that can save her. The only place to get the drug is at the store of a pharmacist who is known to overcharge people for drugs. The man can only pay $1,000, but the pharmacist wants $2,000 and refuses to sell it to him for less or to let him pay later. Desperate, the man later breaks into the pharmacy and steals the medicine. Should he have done that? Was it right or wrong? Why? (Kohlberg, 1984).

Kohlberg examined how individuals responded to this dilemma. The key factor was not whether the person said it was right or wrong for the man to steal the drug, but rather their reasoning. Kohlberg noticed similarities in reasoning about this moral dilemma and theorized that moral development follows a series of qualitatively different stages. Kohlberg’s six stages are generally organized into three levels of moral reasons.

Level 1: Preconventional Morality

Reasoning during Level 1, which is broken into two stages, is based on what would happen to the man as a result of the act, that is, on the consequences of the act. In Stage 1, moral reasoning is based on concepts of punishment. The child believes that if the consequence of an action is punishment, then the action was wrong. For example, they might say the man should not break into the pharmacy because the pharmacist might find him and beat him. In Stage 2, the child bases his or her thinking on self-interest and reward. “You scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours.” They might say that the man should break in and steal the drug and his wife will give him a big kiss. Right or wrong, both decisions were based on what would physically happen to the man as a result of the act. This is a self-centered approach to moral decision-making. He called this most superficial understanding of right and wrong preconventional morality. Preconventional morality focuses on self-interest. Punishment is avoided, and rewards are sought. Adults can also fall into these stages, particularly when they are under pressure.

Level 2: Conventional Morality

Those tested who based their answers on authority, that is, based on what other people would think of the man because of his act, were placed in Level 2. For instance, they might say he should break into the store, and then everyone would think he was a good husband, or he should not because it is against the law. In either case, right and wrong is determined by what other people think. In Stage 3, the person reasons based on mutual expectations and relationships. They want to please others. In Stage 4, the person acknowledges the importance of social norms or laws and wants to be a good member of the group or society. A good decision gains the approval of others or one that complies with the law. This he called conventional morality – when people care about the effect of their actions on others. Some older children, adolescents, and adults use this reasoning.

Level 3: Postconventional Morality

Right and wrong are based on social contracts established for the good of everyone and that can transcend the self and social convention. For example, the man should break into the store because, even if it is against the law, the wife needs the drug, and her life is more important than the consequences the man might face for breaking the law. Alternatively, the man should not violate the principle of the right of property because this rule is essential for social order. In either case, the person’s judgment goes beyond what happens to the self. It is based on a concern for others; for society as a whole, or for an ethical standard rather than a legal standard. This level is called postconventional moral development because it goes beyond convention or what other people think to a higher, universal ethical principle of conduct that may or may not be reflected in the law. Notice that such thinking is the kind Supreme Court justices do all day when deliberating whether a law is moral or ethical, which requires being able to think abstractly. Often this is not accomplished until a person reaches adolescence or adulthood. In Stage 5, laws are recognized as social contracts. The reasons for the laws, like justice, equality, and dignity, are used to evaluate decisions and interpret laws. In Stage 6, individually determined universal ethical principles are weighed to make moral decisions. Kohlberg said that few people ever reach this stage. You can review all six stages under the three levels in the table below.

Components of the Theory of Mind

| Stage | Component | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Desire Psychology (ages 2-3) |

Diverse-Desires | Understanding that two people may have different desires regarding the same object. |

| Belief Psychology (ages 3 or 4 to 5) |

Diverse-Beliefs | Understanding that two people may hold different beliefs about an object. |

| Knowledge Access (knowledge/ignorance) |

Understanding that people may not have access to information. | |

| False Belief | Understanding that someone might hold a belief based on false information. |

Adapted from Lally & Valentine-French, 2019

Influences on Moral Development

What influences moral development? Kohlberg argued that moral development was not an automatic, maturational process, nor was it mechanistic, in that moral development couldn’t simply be taught (Crain, 1985). Instead, he proposed that it develops through repeated practice in situations where children must think together with adults or peers about moral problems: where their viewpoints are challenged or questioned; where they have to consider others’ perspectives and perhaps revise their own; and where they must try to coordinate their own desires and those of others with the help of moral rules. Moreover, it is our active engagement with these thought processes that helps our development (Berkowitz & Gibbs, 1983). This engagement can occur in many contexts; three notable ones are our caregivers, our schooling, and our peers (Berk, 2014, p. 326).

Studies suggest that caregivers’ use of an authoritative parenting style helps children reach higher stages of moral reasoning (Pratt, Skoe, & Arnold, 2004). This style emphasizes care, consistent and fair expectations, and support for autonomy in ways such as discussing the reasoning for rules and encouraging children’s own perspectives. These aspects of parenting can help children practice their own moral reasoning, allow them to internalize true moral principles, and over time act on them under conditions of greater difficulty (aka temptation). On the other hand, the use of threats and lectures does not help moral reasoning (Walker & Taylor, 1991). Studies suggest that children remember the negative effects and exertion of force, which interferes with the internalization of moral principles.

Education is another important venue for practicing moral reasoning. In general, the more years individuals dedicate to schooling, the higher their average level of moral reasoning (Dawson, 2002). In particular, schools help promote moral reasoning when they offer students exposure to diverse experiences and ways of being, role-taking and perspective-taking opportunities, and chances to discuss and defend their viewpoints (Comunian & Gielen, 2006; Mason & Gibbs, 1993).

Within schools and outside of them, peers are important relational partners for developing moral reasoning. As opposed to conversations with parents or teachers, which are hierarchical, peers are on more equal footing. With peers, individuals need to practice communicating their own needs and considering the needs of their friends to reach decisions and resolve conflicts (Killen & Nucci, 1995).

Critiques of Kohlberg’s Theory

Although research has supported Kohlberg’s idea that moral reasoning changes from an early emphasis on punishment, social rules, and regulations to an emphasis on more general ethical principles, as with Piaget’s approach, Kohlberg’s stage model is probably too simple. First, people may use higher levels of reasoning for some types of problems but revert to lower levels in situations where doing so is more consistent with their goals or beliefs (Rest, 1979). Second, it has been argued that the stage model is particularly appropriate for Western, rather than non-Western, samples in which allegiance to social norms, such as respect for authority, may be particularly important (Haidt, 2001). In addition, there is frequently little correlation between how we score on the moral stages and how we behave in real life.

Perhaps the most important critique of Kohlberg’s theory is that it emphasizes justice without incorporating compassion and other moral considerations, and in doing so might describe the moral development of males better than it describes that of females (who were not represented in Kohlberg’s initial research). Gilligan (1982) has argued that, because of differences in their socialization, males tend to value principles of justice and rights, whereas females value caring for and helping others. She argued for an “ethic of care,” emphasizing our human responsibilities to one another and consideration for others. Although there is little evidence for a gender difference in Kohlberg’s stages of moral development (Turiel, 1998), there is some evidence that girls and women tend to focus more on issues of caring, helping, and connecting with others than do boys and men (Jaffee & Hyde, 2000). Despite these trends in the relative priorities of caring and justice, evidence suggests that people of all genders consider both justice and caring to some extent in their moral decisions (Berk, 2014; Walker, 1995).

12.4 Gilligan’s Morality of Care

Gilligan proposed three moral positions that represent different extents or breadth of ethical care. Unlike Kohlberg or Piaget, she does not claim that the positions form a strictly developmental sequence, but only that they can be ranked hierarchically according to their depth or subtlety. In this respect, her theory is “semi-developmental” in a way similar to Maslow’s theory of motivation (Brown & Gilligan, 1992; Taylor, Gilligan, & Sullivan, 1995). The table below summarizes the three moral positions from Gilligan’s theory.

Gilligan’s Positions of Morality

| Moral Position | Definition of what is morally good |

|---|---|

| Position 1: Survival orientation | Action that considers one's personal needs only |

| Position 2: Conventional care | Action that considers others' needs or preferences, but not necessarily one's own |

| Position 3: Integrated care | Action that attempts to coordinate one's own needs with those of others |

Position 1: Caring as Survival

The most basic kind of caring is a survival orientation, in which a person is concerned primarily with his or her welfare. If a teenage girl with this ethical position is wondering whether to get an abortion, for example, she will be concerned entirely with the effects of the abortion on herself. The morally good choice will be whatever creates the least stress for herself, and that disrupts her own life the least. Responsibilities to others (the baby, the father, or her family) play little or no part in her thinking.

As a moral position, a survival orientation is obviously not satisfactory for classrooms on a widespread scale. If every student only looked out for himself or herself, classroom life might become rather unpleasant! Nonetheless, there are situations in which focusing primarily on yourself is both a sign of good mental health and relevant to teachers. For a child who has been bullied at school or sexually abused at home, for example, it is both healthy and morally desirable to speak out about how bullying or abuse has affected the victim. Doing so means essentially looking out for the victim’s own needs at the expense of others’ needs, including the bullies or abusers. Speaking out, in this case, requires a survival orientation and is healthy because the child is taking care of herself.

Position 2: Conventional Caring

A more subtle moral position is caring for others, in which a person is concerned about others’ happiness and welfare, and about reconciling or integrating others’ needs where they conflict with each other. In considering an abortion, for example, the teenager in this position would think primarily about what other people prefer. Do the father, her parents, and/or her doctor want her to keep the child? The morally good choice becomes whatever will please others the best. This position is more demanding than Position 1, ethically, and intellectually, because it requires coordinating several persons’ needs and values. Nevertheless, it is often morally insufficient because it ignores one crucial person: the self.

A more subtle moral position is caring for others, in which a person is concerned about others’ happiness and welfare, and about reconciling or integrating others’ needs where they conflict with each other. In considering an abortion, for example, the teenager in this position would think primarily about what other people prefer. Do the father, her parents, and/or her doctor want her to keep the child? The morally good choice becomes whatever will please others the best. This position is more demanding than Position 1, ethically, and intellectually, because it requires coordinating several persons’ needs and values. Nevertheless, it is often morally insufficient because it ignores one crucial person: the self.

In classrooms, students who operate from Position 2 can be very desirable in some ways; they can be eager to please, considerate, and good at fitting in and working cooperatively with others. Because these qualities are usually welcome in a busy classroom, teachers can be tempted to reward students for developing and using them. The problem with rewarding Position 2 ethics, however, is that doing so neglects the student’s development—his or her own academic and personal goals or values. Sooner or later, personal goals, values, and identity need attention and care, and educators have a responsibility to assist students in discovering and clarifying them.

Position 3: Integrated Caring

The most developed form of moral caring in Gilligan’s model is integrated caring, the coordination of personal needs and values with those of others. Now the morally good choice takes account of everyone, including yourself, not everyone except yourself. In considering an abortion, a woman at Position 3 would think not only about the consequences for the father, the unborn child, and her family but also about the consequences for herself. How would bearing a child affect her own needs, values, and plans? This perspective leads to moral beliefs that are more comprehensive but ironically are also more prone to dilemmas because the widest possible range of individuals is being considered.

In classrooms, integrated caring is most likely to surface whenever teachers give students wide, sustained freedom to make choices. If students have little flexibility in their actions, there is little room for considering anyone’s needs or values, whether their own or others’. If the teacher says simply: “Do the homework on page 50 and turn it in tomorrow morning,” then the main issue becomes compliance, not a moral choice. Suppose instead that she says something like this: “Over the next two months, figure out an inquiry project about the use of water resources in our town. Organize it any way you want—talk to people, read widely about it, and share it with the class in a way that all of us, including yourself, will find meaningful.” An assignment like this poses moral challenges that are not only educational but also moral since it requires students to make value judgments. Why? For one thing, students must decide what aspect of the topic matters to them. Such a decision is partly a matter of personal values. For another thing, students have to consider how to make the topic meaningful or important to others in the class. Third, because the timeline for completion is relatively far in the future, students may have to weigh personal priorities (like spending time with friends or family) against educational priorities (working on the assignment a bit more on the weekend). As you might suspect, some students might have trouble making good choices when given this sort of freedom—and their teachers might, therefore, be cautious about giving such an assignment.

Nevertheless, the difficulties in making choices are part of Gilligan’s point: integrated caring is indeed more demanding than caring based only on survival or on consideration of others. Not all students may be ready for it.

References

Berkowitz, M., & Gibbs, J. (1983). Measuring the Developmental Features of Moral Discussion. Merrill Palmer Quarterly, 29(4), 399-410. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23086309

Birch, S., & Bloom, P. (2003). Children are cursed: An asymmetric bias in mental-state attribution. Psychological Science, 14(3), 283-286.

Comunian, A. L., & Gielen, U. P. (2006). Promotion of moral judgement maturity through stimulation of social role‐taking and social reflection: An Italian intervention study. Journal of Moral Education, 35(1), 51-69.

Crain, W.C. (1985). Theories of Development. Prentice-Hall. pp. 118-136.

Dawson, T. L. (2002). New tools, new insights: Kohlberg’s moral judgement stages revisited. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 26(2), 154-166.

Epley, N., Morewedge, C. K., & Keysar, B. (2004). Perspective taking in children and adults: Equivalent egocentrism but differential correction. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40, 760–768.

Frank, G., Plunkett, S. W., & Otten, M. P. (2010). Perceived parenting, self-esteem, and general self-efficacy of Iranian American adolescents. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 19, 738-746.

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Harvard University Press.

Haidt, J. (2001). The emotional dog and its rational tail: A social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychological Review, 108(4), 814–834.

Jaffee, S., & Hyde, J. S. (2000). Gender differences in moral orientation: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 126(5), 703–726.

Killen, M., & Nucci, L. P. (1995). Morality, autonomy, and social conflict. In M. Killen & D. Hart (Eds.), Morality in everyday life: Developmental perspectives (pp. 52–86). Cambridge University Press.

Kochanska, G. (2002). Mutually responsive orientation between mothers and their young children: A context for the early development of conscience. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 11(6), 191-195.

Kohlberg, L. (1963). The development of children’s orientations toward a moral order: Sequence in the development of moral thought. Vita Humana, 16, 11-36.

Kohlberg, L. (1984). The psychology of moral development: Essays on moral development (Vol. 2, p. 200). Harper & Row.

Mason, M. G., & Gibbs, J. C. (1993). Social perspective taking and moral judgment among college students. Journal of Adolescent Research, 8(1), 109–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/074355489381008

McAlister, A. R., & Peterson, C. C. (2007). A longitudinal study of siblings and theory of mind development. Cognitive Development, 22, 258-270.

Perner, J., Ruffman, T., & Leekam, S. R. (1994). Theory of mind is contagious: You catch from your sibs. Child Development, 65, 1228-1238.

Pratt, M., Skoe, E., & Arnold, M. L. (2004). Care reasoning development and family socialisation patterns in later adolescence: A longitudinal analysis. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 28(2), 140-147.

Shahaeian, A., Peterson, C. C., Slaughter, V., & Wellman, H. M. (2011). Culture and the sequence of steps in theory of mind development. Developmental Psychology, 47(5), 1239-1247.

Thompson, R. A. (2012). Whither the preconventional child? Toward a life‐span moral development theory. Child Development Perspectives, 6(4), 423-429.

Turiel, E. (1998). The development of morality. In W. Damon (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Socialization (5th ed., Vol. 3, pp. 863–932). John Wiley & Sons.

Walker, L. J. (1995). Sexism in Kohlberg’s moral psychology? In W. M. Kurtines & J. L. Gerwitz (Eds.), Moral development: An introduction (pp. 83-107). Allyn and Bacon.

Walker, L. J., & Taylor, J. H. (1991). Stage transitions in moral reasoning: A longitudinal study of developmental processes. Developmental Psychology, 27(2), 330-337. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.27.2.330

Wellman, H.M., Cross, D., & Watson, J. (2001). Meta-analysis of theory of mind development: The truth about false belief. Child Development, 72(3), 655-684.

Wellman, H. M., Fang, F., Liu, D., Zhu, L, & Liu, L. (2006). Scaling theory of mind understandings in Chinese children. Psychological Science, 17, 1075-1081.

Wimmer, H., & Perner, J. (1983). Beliefs about beliefs: Representation and constraining function of wrong beliefs in young children’s understanding of deception. Cognition, 13, 103–128.

Media Attributions

- CARE_International_–_friendship_and_love © Care International is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license