13 Socioemotional Development and Attachment to Others

Learning Objectives

- Explain self-concept and self-esteem

- Describe infant emotions, self-awareness, stranger wariness, and separation anxiety

- Explain how emotions influence thoughts and behavior

- Describe the emotional development over the lifespan

- Describe the impact of attachment theory on development

- Differentiate styles of attachment according to the Strange Situation Technique

- Explain the factors that influence attachment

- Describe the interplay between personality and

This chapter begins the third portion of our course, which will focus on the psychosocial development of humans. Psychosocial development involves the growth of social skills, emotional competence, personality, sense of self, and interpersonal relationships with others. Within the psychosocial framework, the study of emotions in the field of lifespan development has gained increasing importance and will be where we begin our discussion (Stanrock, 2020). The second half of this chapter will explore personality, temperament, and attachment. Understanding adult attachment styles, temperament, and personality provides valuable insight into how ourselves and others approach relationships.

13.1 Emotions

Like actors on a stage, humans move through the scenes of life, expressing and receiving a range of emotions in every interaction and encounter. An emotion is a subjective state of being that humans often describe as “feelings”. Emotions result from the combination of subjective experience, expression, cognitive appraisal, and physiological responses (Levenson, Carstensen, Friesen, & Ekman, 1991). However, the exact order in which these components occur is not clear, and some parts may even happen at the same time. An emotion often begins with a subjective (individual) experience, which is a stimulus. Often the stimulus is external, but it does not have to be from the outside world. For example, it might be that one thinks about war and becomes sad, even though they never experienced war. Emotional expression refers to the manner one uses to display an emotion, through nonverbal and verbal behaviors (Gross, 1999). Humans perform cognitive appraisals, in which, a person analyzes the way they will be impacted by a situation (Roseman & Smith, 2001). In addition, emotions include physiological responses, such as possible changes in heart rate, sweating, etc. (Soussignan, 2002).

Emotions are rapid information-processing systems that help us act with minimal thinking (Tooby & Cosmides, 2008). Problems associated with birth, battle, death, and seduction have occurred throughout evolutionary history and emotions evolved to aid humans in adapting to those problems rapidly and with minimal conscious cognitive intervention. If we did not have emotions, we could not make rapid decisions concerning whether to attack, defend, flee, care for others, reject food, or approach something useful, all of which were functionally adaptive in our evolutionary history and helped us to survive. For instance, drinking spoiled milk or eating rotten eggs has negative consequences for our welfare. The emotion of disgust, however, helps us take immediate action by not ingesting them in the first place or by vomiting them out. This response is adaptive because it aids, ultimately, in our survival and allows us to act immediately without much thinking. In some instances, taking the time to sit and rationally think about what to do, calculating cost–benefit ratios in one’s mind, is a luxury that might cost one’s life. Emotions evolved so that we can act without that depth of thinking.

Emotions Prepare the Body for Immediate Action

Emotions prepare us for behavior. When triggered, emotions orchestrate systems such as perception, attention, inference, learning, memory, goal choice, motivational priorities, physiological reactions, motor behaviors, and behavioral decision-making (Cosmides & Tooby, 2000; Tooby & Cosmides, 2008). Emotions simultaneously activate certain systems and deactivate others to prevent the chaos of competing systems operating at the same time, allowing for coordinated responses to environmental stimuli (Levenson, 1999). For instance, when we are afraid, our bodies shut down temporarily unneeded digestive processes, resulting in saliva reduction (a dry mouth); blood flows disproportionately to the lower half of the body; the visual field expands; and the air is breathed in, all preparing the body to flee. Emotions initiate a system of components that includes subjective experience, expressive behaviors, physiological reactions, action tendencies, and cognition, all for specific actions; the term “emotion” is a metaphor for these reactions.

One common misunderstanding many people have when thinking about emotions, however, is the belief that emotions must always directly produce action. This is not true. Emotion certainly prepares the body for action; but whether people actually engage in action is dependent on many factors, such as the context within which the emotion has occurred, the target of the emotion, the perceived consequences of one’s actions, previous experiences, and so forth (Baumeister, Vohs, DeWall, & Zhang, 2007; Matsumoto & Wilson, 2008). Thus, emotions are just one of many determinants of behavior, albeit an important one.

Emotions Influence Thoughts

Emotions are also connected to thoughts and memories. Memories are not just facts that are encoded in our brains; they are colored with the emotions felt at those times the facts occurred (Wang & Ross, 2007). Thus, emotions serve as the neural glue that connects those disparate facts in our minds. That is why it is easier to remember happy thoughts when happy, and angry times when angry. Emotions serve as the affective basis of many attitudes, values, and beliefs that we have about the world and the people around us; without emotions those attitudes, values, and beliefs would be just statements without meaning, and emotions give those statements meaning. Emotions influence our thinking processes, sometimes in constructive ways, sometimes not. It is difficult to think critically and clearly when we feel intense emotions, but easier when we are not overwhelmed with emotions (Matsumoto, Hirayama, & LeRoux, 2006).

Emotions Motivate Future Behaviors

Because emotions prepare our bodies for immediate action, influence thoughts, and can be felt, they are important motivators of future behavior. Many of us strive to experience the feelings of satisfaction, joy, pride, or triumph in our accomplishments and achievements. At the same time, we also work very hard to avoid strong negative feelings; for example, once we have felt the emotion of disgust when drinking the spoiled milk, we generally work very hard to avoid having those feelings again (e.g., checking the expiration date on the label before buying the milk, smelling the milk before drinking it, watching if the milk curdles in one’s coffee before drinking it). Emotions, therefore, not only influence immediate actions but also serve as an important motivational basis for future behaviors. (64)

Interpersonal Functions of Emotion

Emotions are expressed both verbally through words and nonverbally through facial expressions, voices, gestures, body postures, and movements. We are constantly expressing emotions when interacting with others, and others can reliably judge those emotional expressions (Elfenbein & Ambady, 2002; Matsumoto, 2001); thus, emotions have signal value to others and influence others and our social interactions. Emotions and their expressions communicate information to others about our feelings, intentions, relationship with the target of the emotions, and the environment. Because emotions have this communicative signal value, they help solve social problems by evoking responses from others, signaling the nature of interpersonal relationships, and providing incentives for desired social behavior (Keltner, 2003).

Emotional Expressions Facilitate Specific Behaviors in Perceivers

Because facial expressions of emotion are social signals, they contain meaning not only about the expressor’s psychological state but also about that person’s intent and subsequent behavior. This information affects what the perceiver is likely to do. People observing fearful faces, for instance, are more likely to produce approach-related behaviors, whereas people who observe angry faces are more likely to produce avoidance-related behaviors (Marsh, Ambady, & Kleck, 2005). Even subliminal presentation of smiles produces increases in how much beverage people pour and consume and how much they are willing to pay for it; presentation of angry faces decreases these behaviors (Winkielman, Berridge, & Wilbarger, 2005). Also, emotional displays evoke specific, complementary emotional responses from observers; for example, anger evokes fear in others (Dimberg & Ohman, 1996; Esteves, Dimberg, & Ohman, 1994), whereas distress evokes sympathy and aid (Eisenberg et al., 1989).

Emotional Expressions Signal the Nature of Interpersonal Relationships

Emotional expressions provide information about the nature of the relationships among the individuals. Some of the most important and provocative findings in this area come from studies involving married couples (Gottman & Levenson, 1992; Gottman, Levenson, & Woodin, 2001). In this research, married couples visited a laboratory after having not seen each other for 24 hours, and then engaged in intimate conversations about daily events or issues of conflict. Discrete expressions of contempt, especially by the men, and disgust, especially by the women, predicted later marital dissatisfaction and even divorce.

Emotional Expressions Provide Incentives for Desired Social Behavior

Facial expressions of emotion are important regulators of social interaction. In the developmental literature, this concept has been investigated under the concept of social referencing (Klinnert, Campos, & Sorce, 1983); that is, the process whereby infants seek out information from others to clarify a situation and then use that information to act. To date, the strongest demonstration of social referencing comes from work on the visual cliff. In the first study to investigate this concept, Campos and colleagues (Sorce, Emde, Campos, & Klinnert, 1985) placed mothers on the far end of the “cliff” from the infant. Mothers first smiled at the infants and placed a toy on top of the safety glass to attract them; infants invariably began crawling to their mothers. When the infants were in the center of the table, however, the mother then posed an expression of fear, sadness, anger, interest, or joy. The results were different for the different faces; no infant crossed the table when the mother showed fear; only 6% did when the mother posed anger, 33%; crossed when the mother posed sadness, and approximately 75 %; of the infants crossed when the mother posed joy or interest.

Other studies provide similar support for facial expressions as regulators of social interaction. In one study (Bradshaw, 1986), experimenters posed facial expressions of neutral, anger, or disgust toward babies as they moved toward an object and measured the amount of inhibition the babies showed in touching the object. The results for 10– and 15–month–olds were the same: anger produced the greatest inhibition, followed by disgust, with neutral the least. This study was later replicated (Hertenstein & Campos, 2004) using joy and disgust expressions, altering the method so that the infants were not allowed to touch the toy (compared with a distractor object) until one hour after exposure to the expression. At 14 months of age, significantly more infants touched the toy when they saw joyful expressions, but fewer touched the toy when the infants saw disgust. (64)

13.2 Infant Emotions

At birth, infants exhibit two emotional responses: Attraction and withdrawal. They show attraction to pleasant situations that bring comfort, stimulation, and pleasure, and they withdraw from unpleasant stimulation such as bitter flavors or physical discomfort. At around two months, infants exhibit social engagement in the form of social smiling as they respond with smiles to those who engage their positive attention (Lavelli & Fogel, 2005).

At birth, infants exhibit two emotional responses: Attraction and withdrawal. They show attraction to pleasant situations that bring comfort, stimulation, and pleasure, and they withdraw from unpleasant stimulation such as bitter flavors or physical discomfort. At around two months, infants exhibit social engagement in the form of social smiling as they respond with smiles to those who engage their positive attention (Lavelli & Fogel, 2005).

Social smiling becomes more stable and organized as infants learn to use their smiles to engage their parents in interactions. Pleasure is expressed as laughter at 3 to 5 months of age, and displeasure becomes more specific as fear, sadness, or anger between ages 6 and 8 months. Anger is often the reaction to being prevented from obtaining a goal, such as a toy being removed (Braungart-Rieker et al., 2010). In contrast, sadness is typically the response when infants are deprived of a caregiver (Papousek, 2007). Fear is often associated with the presence of a stranger, known as stranger wariness, or the departure of significant others known as separation anxiety. Both appear sometime between 6 and 15 months after object permanence has been acquired. Further, there is some indication that infants may experience jealousy as young as 6 months of age (Hart & Carrington, 2002).

Emotions are often divided into two general categories:

- Basic emotions, such as interest, happiness, anger, fear, surprise, sadness, and disgust, which appear first, and

- Self-conscious emotions, such as envy, pride, shame, guilt, doubt, and embarrassment. Unlike primary emotions, secondary emotions appear as children start to develop a self-concept and require social instruction on when to feel such emotions.

The situations in which children learn self-conscious emotions vary from culture to culture. Individualistic cultures teach us to feel pride in personal accomplishments, while in more collective cultures children are taught to not call attention to themselves unless they wish to feel embarrassed for doing so (Akimoto & Sanbinmatsu, 1999).

Facial expressions of emotion are important regulators of social interaction. In the developmental literature, this has been investigated under the concept of social referencing; that is, the process whereby infants seek out information from others to clarify a situation and then use that information to act (Klinnert et al., 1983). To date, the strongest demonstration of social referencing comes from work on the visual cliff. In the first study to investigate this concept, Sorce et al. (1985) placed mothers on the far end of the “cliff” from the infant. Mothers first smiled at the infants and placed a toy on top of the safety glass to attract them; infants invariably began crawling to their mothers. When the infants were in the center of the table, however, the mother then posed an expression of fear, sadness, anger, interest, or joy. The results were clearly different for the different faces; no infant crossed the table when the mother showed fear; only 6% did when the mother posed anger, 33% crossed when the mother posed sadness, and approximately 75% of the infants crossed when the mother posed joy or interest.

Other studies provide similar support for facial expressions as regulators of social interaction. Experimenters posed facial expressions of neutral, anger, or disgust toward babies as they moved toward an object and measured the amount of inhibition the babies showed in touching the object (Bradshaw, 1986). The results for 10- and 15-month-olds were the same: Anger produced the greatest inhibition, followed by disgust, with neutral the least. This study was later replicated using joy and disgust expressions, altering the method so that the infants were not allowed to touch the toy (compared with a distractor object) until one hour after exposure to the expression (Hertenstein & Campos, 2004). At 14 months of age, significantly more infants touched the toy when they saw joyful expressions, but fewer touched the toy when the infants saw disgust.

A final emotional change is in self-regulation. Emotional self-regulation refers to strategies we use to control our emotional states so that we can attain goals (Thompson & Goodvin, 2007). This requires effortful control of emotions and initially requires assistance from caregivers (Rothbart et al., 2006). Young infants have very limited capacity to adjust their emotional states and depend on their caregivers to help soothe themselves. Caregivers can offer distractions to redirect the infant’s attention and comfort to reduce emotional distress. As areas of the infant’s prefrontal cortex continue to develop, infants can tolerate more stimulation. By 4 to 6 months, babies can begin to shift their attention away from upsetting stimuli (Rothbart et al, 2006). Older infants and toddlers can more effectively communicate their need for help and can crawl or walk toward or away from various situations (Cole et al., 2010). This aids in their ability to self-regulate. Temperament also plays a role in children’s ability to control their emotional states, and individual differences have been noted in the emotional self-regulation of infants and toddlers (Rothbart & Bates, 2006).

13.3 Development of the Sense of Self

During the second year of life, children begin to recognize themselves as they gain a sense of self as an object. In a classic experiment by Lewis and Brooks (1978), children 9 to 24 months of age were placed in front of a mirror after a spot of rouge was placed on their nose as their mothers pretended to wipe something off the child’s face. If the child reacted by touching his or her nose rather than that of the “baby” in the mirror, it was taken to suggest that the child recognized the reflection as him- or herself. Lewis and Brooks found that somewhere between 15 and 24 months most infants developed a sense of self-awareness. Self-awareness is the realization that you are separate from others (Kopp, 2011). Once a child has achieved self-awareness, the child is moving toward understanding social emotions such as guilt, shame, or embarrassment, as well as sympathy or empathy.

Early childhood is a time of forming an initial sense of self. Self-concept is our self-description according to various categories, such as our external and internal qualities. Self-concept refers to beliefs about general personal identity (Seiffert, 2011). These beliefs include personal attributes, such as one’s age, physical characteristics, behaviors, and competencies. Children in middle and late childhood have a more realistic sense of self than do those in early childhood, and they better understand their strengths and weaknesses. This can be attributed to greater experience in comparing their own performance with that of others, and to greater cognitive flexibility. Children in middle and late childhood are also able to include other peoples’ appraisals of them into their self-concept, including parents, teachers, peers, culture, and media.

In contrast, self-esteem is an evaluative judgment about who we are. The emergence of cognitive skills in this age group results in improved perceptions of the self. If asked to describe yourself to others you would likely provide some physical descriptors, group affiliation, personality traits, behavioral quirks, values, and beliefs. When researchers ask young children the same open-ended question, the children provide physical descriptors, preferred activities, and favorite possessions. Thus, a three-year-old might describe herself as a three-year-old girl with red hair, who likes to play with Legos. This focus on external qualities is referred to as the categorical self.

However, even children as young as three know there is more to themselves than these external characteristics. Harter and Pike (1984) challenged the method of measuring personality with an open-ended question as they felt that language limitations were hindering the ability of young children to express their self-knowledge. They suggested a change to the method of measuring self-concept in young children, whereby researchers provide statements that ask whether something is true of the child (e.g., “I like to boss people around”, “I am grumpy most of the time”). Consistent with Harter and Pike’s suspicions, those in early childhood answer these statements in an internally consistent manner, especially after the age of four (Goodvin et al., 2008), and often give similar responses to what others (parents and teachers) say about the child (Brown et al., 2008; Colwell & Lindsey, 2003).

Young children tend to have a generally positive self-image. This optimism is often the result of a lack of social comparison when making self-evaluations (Ruble et al., 1980), and with a comparison between what the child once could do to what they can do now (Kemple, 1995). However, this does not mean that preschool children are exempt from negative self-evaluations. Preschool children with insecure attachments to their caregivers tend to have lower self-esteem at age four (Goodvin et al., 2008). Maternal negative affect was also found by Goodwin and her colleagues to produce more negative self-evaluations in preschool children.

Self-Control

Self-control is not a single phenomenon but is multi-faceted. It includes response initiation, the ability to not initiate a behavior before you have evaluated all the information, response inhibition, the ability to stop a behavior that has already begun, and delayed gratification, the ability to hold out for a larger reward by forgoing a smaller immediate reward (Dougherty et al., 2005). It is in early childhood that we see the start of self-control, a process that takes many years to fully develop. In the now classic “Marshmallow Test” (Mischel et al., 1972) children are confronted with the choice of a small immediate reward (a marshmallow) and a larger delayed reward (more marshmallows). Walter Mischel and his colleagues over the years have found that the ability to at the age of four predicted better academic performance and health later in life (Mischel, et al., 2011). Self-control is related to executive function, discussed earlier in the chapter. As executive function improves, children become less impulsive (Traverso et al., 2015).

Self-concept and Self-esteem in Adolescence

In adolescence, teens continue to develop their self-concept. Their ability to think of the possibilities and to reason more abstractly may explain the further differentiation of the self during adolescence. However, the teen’s understanding of self is often full of contradictions. Young teens may see themselves as outgoing but also withdrawn, happy yet often moody, and both smart and completely clueless (Harter, 2012). These contradictions, along with the teen’s growing recognition that their personality and behavior seem to change depending on who they are with or where they are, can lead the young teen to feel like a fraud. With their parents they may seem angrier and sullen, with their friends they are more outgoing and goofier, and at work, they are quiet and cautious. “Which one is really me?” may be the refrain of the young teenager. Harter (2012) found that adolescents emphasize traits such as being friendly and considerate more than do children, highlighting their increasing concern about how others may see them. Harter also found that older teens add values and moral standards to their self-descriptions.

As self-concept differentiates, so too does self-esteem. In addition to the academic, social, appearance, and physical/athletic dimensions of self-esteem in middle and late childhood, teens also add perceptions of their competency in romantic relationships, on the job, and in close friendships (Harter, 2006). Self-esteem often drops when children transition from one school setting to another, such as shifting from elementary to middle school, or junior high to high school (Ryan et al., 2013). These drops are usually temporary unless there are additional stressors such as parental conflict, or other family disruptions (De Wit et al., 2011). Self-esteem rises from mid to late adolescence for most teenagers, especially if they feel competent in their peer relationships, their appearance, and athletic abilities (Birkeland et al., 2012).

13.4 Temperament

Perhaps you have spent time with a number of infants. How were they alike? How did they differ? How do you compare with your siblings or other children you have known well? You may have noticed that some seemed to be in a better mood than others and that some were more sensitive to noise or more easily distracted than others. These differences may be attributed to temperament. Temperament is the innate characteristics of the infant, including mood, activity level, and emotional reactivity, noticeable soon after birth.

Perhaps you have spent time with a number of infants. How were they alike? How did they differ? How do you compare with your siblings or other children you have known well? You may have noticed that some seemed to be in a better mood than others and that some were more sensitive to noise or more easily distracted than others. These differences may be attributed to temperament. Temperament is the innate characteristics of the infant, including mood, activity level, and emotional reactivity, noticeable soon after birth.

In a 1956 landmark study, Chess and Thomas (1996) evaluated 141 children’s temperament based on parental interviews. Referred to as the New York Longitudinal Study, infants were assessed on 9 dimensions of temperament including activity level, rhythmicity (regularity of biological functions), approach/withdrawal (how children deal with new things), adaptability to situations, intensity of reactions, threshold of responsiveness (how intense a stimulus has to be for the child to react), quality of mood, distractibility, attention span, and persistence.

Based on the infants’ behavioral profiles, they were categorized into three general types of temperament:

- Easy Child (40%) who can quickly adapt to routine and new situations, remains calm, is easy to soothe, and usually is in a positive mood.

- Difficult Child (10%) who reacts negatively to new situations, has trouble adapting to routine, is usually negative in mood, and cries frequently.

- Slow-to-Warm-Up Child (15%) has a low activity level, adjusts slowly to new situations, and is often negative in mood.

As can be seen, the percentages do not equal 100% as some children were not able to be placed neatly into one of the categories. Think about how you might approach each type of child in order to improve your interactions with them. An easy child will not need much extra attention, while a slow-to-warm-up child may need to be given advance warning if new people or situations are going to be introduced.

A difficult child may need to be given extra time to burn off their energy. A caregiver’s ability to work well and accurately read the child will enjoy a goodness-of-fit, meaning their styles match and communication and interaction can flow. Parents who recognize each child’s temperament and accept it, will nurture more effective interactions with the child and encourage more adaptive functioning. For example, an adventurous child whose parents regularly take her outside on hikes would provide a good “fit” to her temperament.

Parenting is Bidirectional

Not only do parents affect their children, but children also influence their parents. Child characteristics, such as temperament, affect parenting behaviors and roles. For example, an infant with an easy temperament may enable parents to feel more effective, as they are easily able to soothe the child and elicit smiling and cooing. On the other hand, a cranky or fussy infant elicits fewer positive reactions from his or her parents and may result in parents feeling less effective in the parenting role (Eisenberg et al., 2008). Over time, parents of more difficult children may become more punitive and less patient with their children (Clark et al., 2000; Eisenberg et al., 1999; Kiff et al., 2011). Parents who have a fussy, difficult child are less satisfied with their marriages and have greater challenges in balancing work and family roles (Hyde et al., 2004). Thus, child temperament is one of the child characteristics that influences how parents behave with their children.

Not only do parents affect their children, but children also influence their parents. Child characteristics, such as temperament, affect parenting behaviors and roles. For example, an infant with an easy temperament may enable parents to feel more effective, as they are easily able to soothe the child and elicit smiling and cooing. On the other hand, a cranky or fussy infant elicits fewer positive reactions from his or her parents and may result in parents feeling less effective in the parenting role (Eisenberg et al., 2008). Over time, parents of more difficult children may become more punitive and less patient with their children (Clark et al., 2000; Eisenberg et al., 1999; Kiff et al., 2011). Parents who have a fussy, difficult child are less satisfied with their marriages and have greater challenges in balancing work and family roles (Hyde et al., 2004). Thus, child temperament is one of the child characteristics that influences how parents behave with their children.

Temperament does not change dramatically as we grow up, but we may learn how to work around and manage our temperamental qualities. Temperament may be one of the things about us that stays the same throughout development. In contrast, personality, defined as an individual’s consistent pattern of feeling, thinking, and behaving, is the result of the continuous interplay between biological disposition and experience.

13.5 Personality

Temperament is largely biologically based, although that does not mean that it is genetically determined. Even at birth, a newborn’s neurophysiology has been shaped by the prenatal environment and birth process they experience. Moreover, during the first few months of life, the quality of an infant’s attachment and their experience of early adversity can have marked neurophysiological effects. Even if temperament does not change dramatically as we grow up, it may be modulated as one contributor to our childhood and adult personality. In contrast to temperament, personality, defined as an individual’s consistent pattern of feeling, thinking, and behaving, is the result of the continuous interplay between this initial biological disposition and experience.

Personality also develops from temperament in other ways (Thompson, Winer, & Goodvin, 2010). As children mature biologically, temperamental characteristics are woven into subsequent developments. For example, a newborn with high reactivity may show high levels of impulsive behavior, but as brain-based capacities for self-control mature, these newfound regulatory capacities may reduce impulsive behavior. Or, a newborn who cries frequently does not necessarily have a grumpy personality; over time, with sufficient parental support and an increased sense of security, the child might be less likely to experience and express distress.

In addition, personality is made up of many other features besides temperament. Children’s developing self-concept, their motivations to achieve or to socialize, their values and goals, their coping styles, their sense of responsibility and conscientiousness, and many other qualities are encompassed into personality. These qualities are influenced by biological dispositions, but even more by the child’s experiences with others, particularly in close relationships, that guide the growth of individual characteristics. Indeed, personality development begins with the biological foundations of temperament but becomes increasingly elaborated, extended, and refined over time. The newborn that parents gazed upon becomes an adult with a personality of depth and nuance.

Adult Personality

Does one’s temperament remain stable through the lifespan? Do shy and inhibited babies grow up to be shy adults, while the sociable child continues to be the life of the party? Like most developmental research the answer is more complicated than a simple yes or no. Chess and Thomas (1987), who identified children as easy, difficult, or slow-to-warm-up, found that children identified as easy grew up to become well-adjusted adults, while those who exhibited a difficult temperament were not as well-adjusted as adults.

Kagan (2002) studied the temperamental category of “inhibition to the unfamiliar” in young children. Inhibited infants exposed to unfamiliarity reacted strongly to the stimuli and cried loudly, pumped their limbs, and had an increased heart rate. Research has indicated that these highly reactive children show temperamental stability into early childhood, and Bohlin and Hagekull (2009) found that shyness in infancy was linked to social anxiety in adulthood. An important aspect of the research on inhibition was looking at the response of the amygdala, which is important for fear and anxiety, especially when confronted with possible threatening events in the environment. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (FMRIs) young adults identified as strongly inhibited when they were toddlers showed heightened activation of the amygdala when compared to those identified as uninhibited when toddlers (Davidson & Begley, 2012).

This research does seem to indicate that temperamental stability holds for many individuals through the lifespan, yet we know that one’s environment can also have a significant impact. Recall from our discussion on epigenesis that environmental factors modify gene expression by switching genes on and off. Many cultural and environmental factors can affect one’s temperament, including exposure to teratogens in utero, early exposure to harsh parenting, adversity, or child abuse, supportive child-rearing, stable homes, illnesses, socioeconomic status, etc. Additionally, individuals often choose environments that align with their temperaments, which in turn further strengthens them (Cain, 2012). Individuals are also active in other ways. As they get older, adults can choose how they wish to express their temperaments, deciding for example, that they will not let an inhibited temperament stop them from experiencing adventures, such as travel. In summary, because temperament is neurophysiological, biology appears to be a main reason why temperament remains stable into adulthood. In contrast, the environment appears mainly responsible for changes or modifications in temperament (Clark & Watson, 1999).

Everybody has their own unique personality, that is, their characteristic manner of thinking, feeling, behaving, and relating to others (John, Robins, & Pervin, 2008). Personality traits refer to these characteristic, routine ways of thinking, feeling, and relating to others. Personality integrates one’s temperament with cultural and environmental influences. Consequently, there are signs or indicators of these traits in childhood, but they become particularly evident when the person is an adult. Personality traits are integral to each person’s sense of self, as they involve what people value, how they think and feel about things, what they like to do, and, basically, what they are like most every day throughout much of their lives.

13.6 Attachment to Others

Attachment is the close bond with a caregiver from which the infant derives a sense of security. The formation of attachments in infancy has been the subject of considerable research as attachments have been viewed as foundations for future relationships. Additionally, attachments form the basis for confidence and curiosity as toddlers, and as important influences on self-concept.

Harry Harlow’s Research

In one classic study showing if nursing was the most important factor in attachment, Wisconsin University psychologists Harry and Margaret Harlow investigated the responses of young monkeys. The infants were separated from their biological mothers, and two surrogate mothers were introduced to their cages. One, the wire mother, consisted of a round wooden head, a mesh of cold metal wires, and a bottle of milk from which the baby monkey could drink. The second mother was a foam-rubber form wrapped in a heated terry-cloth blanket. The infant monkeys went to the wire mother for food, but they overwhelmingly preferred and spent significantly more time with the warm terry-cloth mother. The warm terry-cloth mother provided no food but did provide comfort (Harlow, 1958). The infant’s need for physical closeness and touching is referred to as contact comfort. Contact comfort is believed to be the foundation for attachment. Harlow’s’ studies confirmed that babies have social as well as physical needs. Both monkeys and human babies need a secure base that allows them to feel safe. From this base, they can gain the confidence they need to venture out and explore their worlds.

John Bowlby’s Theory

Building on the work of Harlow and others, John Bowlby developed the concept of attachment theory. He defined attachment as the affectional bond or tie that an infant forms with the mother (Bowlby, 1969). An infant must form this bond with a primary caregiver to have normal social and emotional development. In addition, Bowlby proposed that this attachment bond is very powerful and continues throughout life. He used the concept of a secure base to define a healthy attachment between parent and child (Bowlby, 1982). A secure base is a parental presence that gives the child a sense of safety as the child explores the surroundings.

Bowlby said that two things are needed for a healthy attachment: The caregiver must be responsive to the child’s physical, social, and emotional needs; and the caregiver and child must engage in mutually enjoyable interactions (Bowlby, 1969). Additionally, Bowlby observed that infants would go to extraordinary lengths to prevent separation from their parents, such as crying, refusing to be comforted, and waiting for the caregiver to return. He observed that these same expressions were common to many other mammals, and consequently argued that these negative responses to separation serve an evolutionary function. Because mammalian infants cannot feed or protect themselves, they are dependent upon the care and protection of adults for survival. Thus, those infants who were able to maintain proximity to an attachment figure were more likely to survive and reproduce.

Mary Ainsworth and the Strange Situation

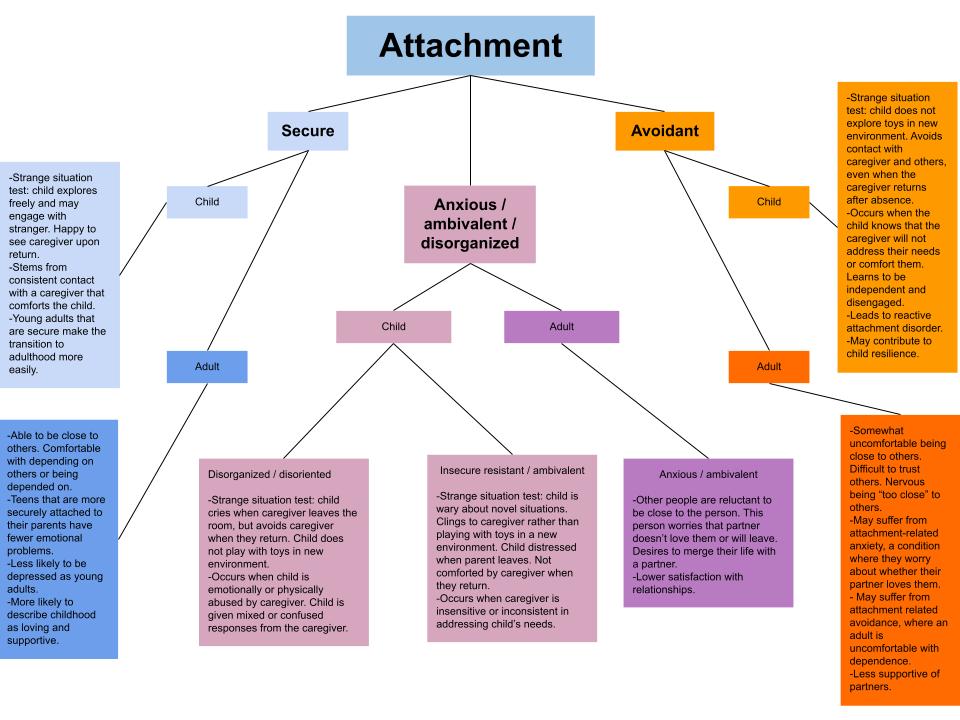

Developmental psychologist Mary Ainsworth, a student of John Bowlby, continued studying the development of attachment in infants. Ainsworth and her colleagues created a laboratory test that measured an infant’s attachment to his or her parent. The test is called The Strange Situation Technique because it is conducted in a context that is unfamiliar to the child and therefore likely to heighten the child’s need for his or her parent (Ainsworth, 1979).

During the procedure, which lasts about 20 minutes, the parent and the infant are first left alone, while the infant explores the room full of toys. Then a strange adult enters the room and talks for a minute to the parent, after which the parent leaves the room. The stranger stays with the infant for a few minutes, and then the parent again enters, and the stranger leaves the room. During the entire session, a video camera records the child’s behaviors, which are later coded by trained coders. The investigators were especially interested in how the child responded to the caregiver leaving and returning to the room, referred to as the “reunion.” Based on their behaviors, the children are categorized into one of four groups where each group reflects a different kind of attachment relationship with the caregiver. One style is secure and the other three styles are referred to as insecure. Review the styles and descriptions in the chart below.

Attachment Styles

| Attachment Style | Description of Style |

|---|---|

| Secure | A child with a secure attachment style usually explores freely while the caregiver is present and may engage with the stranger. The child will typically play with the toys and bring one to the caregiver to show and describe from time to time. The child may be upset when the caregiver departs but is also happy to see the caregiver return. |

| Insecure Resistant (Ambivalent) | A child with an insecure resistant (sometimes called ambivalent) attachment style is wary about the situation in general, particularly the stranger, and stays close or even clings to the caregiver rather than exploring the toys. When the caregiver leaves, the child is extremely distressed and is ambivalent when the caregiver returns. The child may rush to the caregiver but then fails to be comforted when picked up. The child may still be angry and even resist attempts to be soothed. |

| Insecure Avoidant | A child with an avoidant attachment style will avoid or ignore the mother, showing little emotion when the mother departs or returns. The child may run away from the mother when she approaches. The child will not explore very much, regardless of who is there, and the stranger will not be treated much differently from the mother. |

| Insecure Disorganized/Disoriented | A child with a disorganized/disoriented attachment style seems to have an inconsistent way of coping with the stress of the strange situation. The child may cry during the separation, but avoid the mother when she returns, or the child may approach the mother but then freeze or fall to the floor. |

Adapted from Lally & Valentine-French, 2019

How common are the attachment styles among children in the United States? It is estimated that about 65 percent of children in the United States are securely attached. Twenty percent exhibit avoidant styles and 10 to 15 percent are ambivalent. Another 5 to 10 percent may be characterized as disorganized (Ainsworth et al., 1978).

Some cultural differences in attachment styles have been found (Rothbaum et al., 2010). For example, German parents value independence and Japanese mothers are typically by their children’s sides. As a result, the rate of insecure-avoidant attachments is higher in Germany and insecure-resistant attachments are higher in Japan. These differences reflect cultural variation rather than true insecurity, however (van Ijzendoorn & Sagi, 1999). Overall, secure attachment is the most common type of attachment seen in every culture studied thus far (Thompson, 2006).

Caregiver Interactions and the Formation of Attachment

Most developmental psychologists argue that a child becomes securely attached when there is consistent contact from one or more caregivers who meet the physical and emotional needs of the child in a responsive and appropriate manner. However, even in cultures where mothers do not talk, cuddle, and play with their infants, secure attachments can develop (LeVine et. al., 1994).

The insecure ambivalent style occurs when the parent is insensitive and responds inconsistently to the child’s needs. Consequently, the infant is never sure that the world is a trustworthy place or that he or she can rely on others without some anxiety. An unavailable caregiver, perhaps because of marital tension, substance abuse, or preoccupation with work, may send a message to the infant he or she cannot rely on having needs met. An infant who receives only sporadic attention when experiencing discomfort may not learn how to calm down. The child may cry if separated from the caregiver and also cry upon their return. They seek constant reassurance that never seems to satisfy their doubt. Keep in mind that clingy behavior can also just be part of a child’s natural disposition or temperament and does not necessarily reflect some kind of parental neglect. Additionally, a caregiver who attends to a child’s frustration can help teach them to be calm and to relax.

The insecure-avoidant style is marked by insecurity, but this style is also characterized by a tendency to avoid contact with the caregiver and with others. This child may have learned that needs typically go unmet, and that the caregiver does not provide care and cannot be relied upon for comfort, even sporadically. An insecure-avoidant child learns to be more independent and disengaged.

The insecure disorganized/disoriented style represents the most insecure style of attachment and occurs when the child is given mixed, confused, and inappropriate responses from the caregiver. For example, a mother who suffers from schizophrenia may laugh when a child is hurting or cry when a child exhibits joy. The child does not learn how to interpret emotions or to connect with the unpredictable caregiver. This type of attachment is also often seen in children 107 who have been abused. Research has shown that abuse disrupts a child’s ability to regulate their emotions (Main & Solomon, 1990).

Caregiver Consistency

Having a consistent caregiver may be jeopardized if the infant is cared for in a daycare setting with a high turnover of staff or if institutionalized and given little more than basic physical care. Infants who, perhaps because of being in orphanages with inadequate care, have not had the opportunity to attach in infancy may still form initial secure attachments several years later. However, they may have more emotional problems of depression, anger, or be overly friendly as they interact with others (O’Connor et. al., 2003).

Social Deprivation

Severe deprivation of parental attachment can lead to serious problems. According to studies of children who have not been given warm, nurturing care, they may show developmental delays, failure to thrive, and attachment disorders (Bowlby, 1982). Non-organic failure to thrive is the diagnosis for an infant who does not grow, develop, or gain weight on schedule and there is no known medical explanation for this failure. Poverty, neglect, inconsistent parenting, and severe family dysfunction are correlated with non-organic failure to thrive. In addition, postpartum depression can cause even a well-intentioned mother to neglect her infant.

Reactive Attachment Disorder

Children who experience social neglect or deprivation, repeatedly change primary caregivers that limit opportunities to form stable attachments, or are reared in unusual settings (such as institutions) that limit opportunities to form stable attachments can certainly have difficulty forming attachments. According to the DSM-5-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2022), those children experiencing neglectful situations and also displaying markedly disturbed and developmentally inappropriate attachment behavior, such as being inhibited and withdrawn, minimal social and emotional responsiveness to others, and limited positive affect, may be diagnosed with reactive attachment disorder. This disorder often occurs with developmental delays, especially in cognitive and language areas. Fortunately, the majority of severely neglected children do not develop reactive attachment disorder, which occurs in less than 10% of such children. The quality of the caregiving environment after serious neglect affects the development of this disorder.

Resiliency

Being able to overcome challenges and successfully adapt is resiliency. Even young children can exhibit strong resiliency to harsh circumstances. Resiliency can be attributed to certain personality factors, such as an easy-going temperament. Some children are warm, friendly, and responsive, whereas others tend to be more irritable, less manageable, and difficult to console, and these differences play a role in attachment (Gillath et al., 2008; Seifer et al., 1996). It seems safe to say that attachment, like most other developmental processes, is affected by an interplay of genetic and socialization influences.

Receiving support from others also leads to resiliency. A positive and strong support group can help a parent and child build a strong foundation by offering assistance and positive attitudes toward the newborn and parent. In a direct test of this idea, Dutch researcher van den Boom (1994) randomly assigned some babies’ mothers to a training session in which they learned to better respond to their children’s needs. The research found that these mothers’ babies were more likely to show a secure attachment style in comparison to the mothers in a control group that did not receive training.

Attachment in Adulthood

Do early experiences as children shape adult attachment? The majority of research on this issue is retrospective; that is, it relies on adults’ reports of what they recall about their childhood experiences. This kind of work suggests that secure adults are more likely to describe their early childhood experiences with their parents as being supportive, loving, and kind (Hazan & Shaver, 1987). Several longitudinal studies are emerging that demonstrate prospective associations between early attachment experiences and adult attachment styles and/or interpersonal functioning in adulthood. For example, Fraley et al. (2013) found in a sample of more than 700 individuals studied from infancy to adulthood that maternal sensitivity across development prospectively predicted security at age 18. Simpson et al. (2007) found that attachment security, assessed in infancy in the strange situation, predicted peer competence in grades one to three, which, in turn, predicted the quality of friendship relationships at age 16, which, in turn, predicted the expression of positive and negative emotions in their adult romantic relationships at ages 20 to 23.

It is easy to come away from such findings with the mistaken assumption that early experiences “determine” later outcomes. To be clear, attachment theorists assume that the relationship between early experiences and subsequent outcomes is probabilistic, not deterministic. Having supportive and responsive experiences with caregivers early in life is assumed to set the stage for positive social development, but that does not mean that attachment patterns are set in stone. In short, even if an individual has far from optimal experiences in early life, attachment theory suggests that it is possible for that individual to develop well-functioning adult relationships through a number of corrective experiences, including relationships with siblings, other family members, teachers, and close friends. Security is best viewed as a culmination of a person’s attachment history rather than a reflection of his or her early experiences alone. Those early experiences are considered important, not because they determine a person’s fate, but because they provide the foundation for subsequent experiences.

Attachment Styles in Adulthood

| Attachment Style | Description |

|---|---|

| Secure | I find it relatively easy to get close to others and am comfortable depending on others and having them depend on me. I don't often worry about being abandoned or about someone getting too close to me. |

| Avoidant | I am somewhat uncomfortable being close to others. I find it difficult to trust others completely and difficult to allow myself to depend on others. I am nervous if anyone gets too emotionally close to me, and often, love partners want me to be more intimate than I feel comfortable being. |

| Anxious/Ambivalent | I find that others are reluctant to get as emotionally close as I would like. I often worry my partner doesn't love me or won't stay with me. I have fears that I will be abandoned by others. I want to merge completely with another person, and this sometimes scares others away. |

| Adapted from APA Organization |

Hazan and Shaver (1987) described the attachment styles of adults, using the same three general categories proposed by Ainsworth’s research on young children: secure, avoidant, and anxious/ambivalent. Hazan and Shaver developed three brief paragraphs describing the three adult attachment styles. Adults were then asked to think about romantic relationships they were in and select the paragraph that best describes the way they felt, thought, and behaved in these relationships.

Bartholomew (1990) challenged the categorical view of attachment in adults and suggested that adult attachment was best described as varying along two dimensions; attachment-related anxiety and attachment-related avoidance. Attachment-related anxiety refers to the extent to which an adult worries about whether their partner really loves them. Those who score high on this dimension fear that their partner will reject or abandon them (Fraley, Hudson, Heffernan, & Segal, 2015).

Attachment-related avoidance refers to whether an adult can open up to others, and whether they trust and feel they can depend on others. Those who score high on attachment-related avoidance are uncomfortable with opening up and may fear that such dependency may limit their sense of autonomy (Fraley et al., 2015). According to Bartholomew (1990) this would yield four possible attachment styles in adults; secure, dismissing, preoccupied, and fearful-avoidant.

Securely attached adults score lower on both dimensions. They are comfortable trusting their partners and do not worry excessively about their partner’s love for them. Adults with a dismissing style score low on attachment-related anxiety, but higher on attachment-related avoidance. Such adults dismiss the importance of relationships. They trust themselves but do not trust others, and thus do not share their dreams, goals, and fears with others. They do not depend on other people and feel uncomfortable when they have to do so.

Those with a preoccupied attachment are low in attachment-related avoidance, but high in attachment-related anxiety. Such adults are often prone to jealousy and worry that their partner does not love them as much as they need to be loved. Adults whose attachment style is fearful-avoidant score high on both attachment-related avoidance and attachment-related anxiety. These adults want close relationships but do not feel comfortable getting emotionally close to others. They have trust issues with others and often do not trust their own social skills in maintaining relationships.

Research on attachment in adulthood has found that:

- Adults with insecure attachments report lower satisfaction in their relationships (Butzer, & Campbell, 2008; Holland et al., 2012).

- Those high in attachment-related anxiety report more daily conflict in their relationships (Campbell et al., 2005).

- Those with avoidant attachment exhibit less support to their partners (Simpson et al., 2002).

- Young adults show greater attachment-related anxiety than do middle-aged or older adults (Chopik et al., 2013).

- Some studies report that young adults show more attachment-related avoidance (Schindler et al., 2010), while other studies find that middle-aged adults show higher avoidance than younger or older adults (Chopik et al., 2013).

- Young adults with more secure and positive relationships with their parents make the transition to adulthood more easily than do those with more insecure attachments (Fraley, 2013).

- Young adults with secure attachments and authoritative parents were less likely to be depressed than those with authoritarian or permissive parents or who experienced an avoidant or ambivalent attachment (Ebrahimi et al., 2017).

Do people with certain attachment styles attract those with similar styles?

When people are asked what kinds of psychological or behavioral qualities they are seeking in a romantic partner, a large majority of people indicate that they are seeking someone who is kind, caring, trustworthy, and understanding, that is the kinds of attributes that characterize a “secure” caregiver (Chappell & Davis, 1998). However, we know that people do not always end up with others who meet their ideals. Are secure people more likely to end up with secure partners, and, vice versa, are insecure people more likely to end up with insecure partners? The majority of the research that has been conducted to date suggests that the answer is “yes.” Frazier et al. (1996) studied the attachment patterns of more than 83 heterosexual couples and found that, if the man was relatively secure, the woman was also likely to be secure.

One important question is whether these findings exist because (a) secure people are more likely to be attracted to other secure people, (b) secure people are likely to create security in their partners over time, or (c) some combination of these possibilities. Existing empirical research strongly supports the first alternative. For example, when people have the opportunity to interact with individuals who vary in security in a speed-dating context, they express a greater interest in those who are higher in security than those who are more insecure (McClure et al., 2010). However, there is also some evidence that people’s attachment styles mutually shape one another in close relationships. For example, in a longitudinal study, Hudson et al. (2012) found that, if one person in a relationship experienced a change in security, his or her partner was likely to experience a change in the same direction.

References

In progress….

Media Attributions

- baby-3386242_640 © DivvyPixel is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- baby-303071_1280 © cherylholt is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- woman-2566854_640 © StockSnap is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- John_Bowlby is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Andrew Basinski_concept_map © Andrew Basinski is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license