7 The Body

Learning Objectives

- Explain gross and fine motor skills in infants

- Describe improvements in gross and fine motor skills in early and middle childhood

- Summarize overall physical growth patterns during infancy

- Explain the vaccination debate and its consequence

- Identify physical transformations in adolescence

- Describe the effects associated with early and late onset of puberty, and how they differ for boys and girls

- List common impacts of the aging process on the physical body in late adulthood

- Explain what happens to skin, hair, nails, height, and weight across late adulthood

- Identify physical transformations in adolescence related to sexual maturation

- Explain the climacteric, its impact on life and sexuality in midlife, and the differing impacts of aging on women and men

- Describe the theories of aging

We’ll begin this section by reviewing the physical development that occurs during infancy, which starts at birth and continues until the second birthday. At birth, infants are equipped with a number of reflexes, which are involuntary movements in response to stimulation. We will explore these innate reflexes and then consider how these involuntary reflexes are eventually modified through experiences to become voluntary movements and the basis for motor development as skills emerge that allow an infant to grasp food, roll over, and take the first step.

Children in early childhood are physically growing at a rapid pace. If you want to have fun with a child at the beginning of the period, ask them to take their left hand and use it to go over their head to touch their right ear. They cannot do it. Their body proportions are such that they are still built very much like an infant with a very large head and short appendages. By the time the child is five years old though, their arms will have stretched, and their head is becoming smaller in proportion to the rest of their growing bodies. They can accomplish the task easily because of these physical changes. Children enter middle childhood still looking very young and end the stage on the cusp of adolescence. Most children have gone through a growth spurt that makes them look rather grown-up.

Physical changes of puberty mark the onset of adolescence (Lerner & Steinberg, 2009). For both boys and girls, these changes include a growth spurt in height, growth of pubic and underarm hair, and skin changes (e.g., pimples). Boys also experience growth in facial hair and a deepening of their voice. Girls experience breast development and begin menstruating. These pubertal changes are driven by hormones, particularly an increase in testosterone for boys and estrogen for girls. The physical changes that occur during adolescence are greater than those of any other time of life, except for infancy. In some ways, however, the changes in adolescence are more dramatic than those that occur in infancy—unlike infants, adolescents are aware of the changes that are taking place and of what the changes mean.

Physical changes of puberty mark the onset of adolescence (Lerner & Steinberg, 2009). For both boys and girls, these changes include a growth spurt in height, growth of pubic and underarm hair, and skin changes (e.g., pimples). Boys also experience growth in facial hair and a deepening of their voice. Girls experience breast development and begin menstruating. These pubertal changes are driven by hormones, particularly an increase in testosterone for boys and estrogen for girls. The physical changes that occur during adolescence are greater than those of any other time of life, except for infancy. In some ways, however, the changes in adolescence are more dramatic than those that occur in infancy—unlike infants, adolescents are aware of the changes that are taking place and of what the changes mean.

Hippocrates (author of the famous “Hippocratic oath”) believed that “walking is the best medicine.” This was his learned opinion in 400 BCE and there is now considerable, and increasing, evidence that he may have been correct. As we will see, there are simple physiological changes that accompany middle adulthood. These are somewhat inevitable, but the importance of physical activity at this age range would be difficult to overstate looking at the evidence. Exercise does not necessarily mean running marathons, it may simply mean a commitment to briskly using your legs for thirty minutes. “Use it or lose it” is a good mantra —the technical term for the loss of muscle tissue and function as we age is sarcopenia. From age 30, the body loses 3-8% of its muscle mass per decade, and this accelerates after the age of 60 (Volpi et al, 2004). Diet and exercise can ameliorate both the extent and lifestyle consequences of these kinds of processes. [1]

While late adulthood is generally a time of physical decline, there are no set rules as to when and how it happens. We are continually learning more about how to promote greater health during the aging process.

7.1 Motor Development

Infancy

Motor development occurs in an orderly sequence as infants move from reflexive reactions (e.g., sucking and rooting) to more advanced motor functioning. As mentioned during the prenatal section, development occurs according to the Cephalocaudal (from head to tail) and Proximodistal (from the midline outward) principles. For instance, babies first learn to hold their heads up, then to sit with assistance, then to sit unassisted, followed later by crawling, pulling up, cruising or walking while holding on to something, and then unassisted walking (Eisenberg et al., 1989). As motor skills develop, there are certain developmental milestones that young children should achieve. For each milestone, there is an average age, as well as a range of ages in which the milestone should be reached. An example of a developmental milestone is a baby holding up its head. Babies on average can hold up their heads at 6 weeks old, and 90% of babies achieve this between 3 weeks and 4 months old. On average, most babies sit alone at 7 months. Sitting involves both coordination and muscle strength, and 90% of babies achieve this milestone between 5 and 9 months old. If the child is displaying delays on several milestones, that is reason for concern, and the parent or caregiver should check in with the child’s pediatrician. Developmental delays can be identified and addressed through early intervention.

Motor development occurs in an orderly sequence as infants move from reflexive reactions (e.g., sucking and rooting) to more advanced motor functioning. As mentioned during the prenatal section, development occurs according to the Cephalocaudal (from head to tail) and Proximodistal (from the midline outward) principles. For instance, babies first learn to hold their heads up, then to sit with assistance, then to sit unassisted, followed later by crawling, pulling up, cruising or walking while holding on to something, and then unassisted walking (Eisenberg et al., 1989). As motor skills develop, there are certain developmental milestones that young children should achieve. For each milestone, there is an average age, as well as a range of ages in which the milestone should be reached. An example of a developmental milestone is a baby holding up its head. Babies on average can hold up their heads at 6 weeks old, and 90% of babies achieve this between 3 weeks and 4 months old. On average, most babies sit alone at 7 months. Sitting involves both coordination and muscle strength, and 90% of babies achieve this milestone between 5 and 9 months old. If the child is displaying delays on several milestones, that is reason for concern, and the parent or caregiver should check in with the child’s pediatrician. Developmental delays can be identified and addressed through early intervention.

Motor skills refer to our ability to move our bodies and manipulate objects. Gross motor skills focus on large muscle groups that control our head, torso, arms, and legs and involve larger movements (e.g., balancing, running, and jumping). These skills begin to develop first. Examples include moving to bring the chin up when lying on the stomach, moving the chest up, and rocking back and forth on hands and knees. But it also includes exploring an object with one’s feet as many babies do as early as 8 weeks of age if seated in a carrier or other device that frees the hips. This may be easier than reaching for an object with the hands, which requires much more practice (Berk, 2007). Sometimes an infant will try to move toward an object while crawling and surprisingly move backward because of the greater amount of strength in the arms than in the legs.

Fine motor skills focus on the muscles in our fingers, toes, and eyes, and enable coordination of small actions (e.g., grasping a toy, writing with a pencil, and using a spoon). Newborns cannot grasp objects voluntarily but do wave their arms toward objects of interest. At about 4 months of age, the infant can reach for an object, first with both arms and within a few weeks, with only one arm. At this age grasping an object involves the use of the fingers and palm, but no thumbs. This is known as the Palmer Grasp. The use of the thumb comes at about 9 months of age when the infant can grasp an object using the forefinger and thumb. Now the infant uses a Pincer Grasp, and this ability greatly enhances the ability to control and manipulate an object. Infants take great delight in this newfound ability. They may spend hours picking up small objects from the floor and placing them in containers. By 9 months, an infant can also watch a moving object, reach for it as it approaches, and grab it.

Timeline of Developmental Milestones

| Age | Developmental Milestone |

|---|---|

| ~2 months | • Can hold head upright on own • Smiles at the sound of familiar voices and follows movement of eyes |

| ~3 months | • Can raise head and chest from a prone position • Smiles at others • Grasps objects • Rolls from side to back |

| ~4-5 months | • Babbles, laughs, and tries to imitate sounds • Begins to roll from back to side |

| ~6 months | • Moves objects from hand to hand |

| ~7-8 months | • Can sit without support • May begin to crawl • Responds to own name • Finds partially hidden objects |

| ~8-9 months | • Walks while holding on • Babbles “mama” and “dada” • Claps |

| ~11-12 months | • Stands alone • Begins to walk • Says at least one word • Can stack two blocks |

| ~18 months | • Walks independently • Drinks from a cup • Says at least 15 words • Points to body parts |

| ~2 years | • Runs and jumps • Uses two-word sentences • Follows simple instructions • Begins make-believe play |

| ~3 years | • Speaks in multi-word sentences • Sorts objects by shape and color |

| ~4 years | • Draws circles and squares • Rides a tricycle • Gets along with people outside of the family • Gets dressed |

| ~5 years | • Can jump, hop, and skip • Knows name and address • Counts ten or more objects |

Adapted from Lally & Valentine-French, 2019

Early and Middle Childhood

Early childhood is a time of development of both gross and fine motor skills. During this period, children are especially attracted to motion and song. Days are filled with moving, jumping, running, swinging, and clapping, and every place becomes a playground. Even the booth at a restaurant affords the opportunity to slide around in the seat or disappear underneath and imagine being a sea creature in a cave! Of course, this can be frustrating to a caregiver, but it’s the business of early childhood. Children may frequently ask their caregivers to “look at me” while they hop or roll down a hill. Children’s songs are often accompanied by arm and leg movements or cues to turn around or move from left to right. Running, jumping, dancing movements, etc. all afford children the ability to improve their gross motor skills.

Early childhood is a time of development of both gross and fine motor skills. During this period, children are especially attracted to motion and song. Days are filled with moving, jumping, running, swinging, and clapping, and every place becomes a playground. Even the booth at a restaurant affords the opportunity to slide around in the seat or disappear underneath and imagine being a sea creature in a cave! Of course, this can be frustrating to a caregiver, but it’s the business of early childhood. Children may frequently ask their caregivers to “look at me” while they hop or roll down a hill. Children’s songs are often accompanied by arm and leg movements or cues to turn around or move from left to right. Running, jumping, dancing movements, etc. all afford children the ability to improve their gross motor skills.

Fine motor skills are also being refined in activities such as pouring water into a container, drawing, coloring, and using scissors. Some children’s songs promote fine motor skills as well (have you ever heard of the song “itsy, bitsy, spider”?). Mastering the fine art of cutting one’s fingernails or tying their shoes will take a lot of practice and maturation. Fine motor skills continue to develop in middle childhood, but for preschoolers, the type of play that deliberately involves these skills is emphasized.

During middle childhood, physical growth slows down. One result of the slower rate of growth is an improvement in motor skills. Children of this age tend to sharpen their abilities to perform both gross motor skills such as riding a bike and fine motor skills such as cutting their fingernails.

7.2 Physical Growth & Health

Infancy

The average newborn weighs approximately 7.5 pounds, although a healthy birth weight for a full-term baby is considered to be between 5 pounds, 8 ounces (2,500 grams), and 8 pounds, 13 ounces (4,000 grams).[1] The average length of a newborn is 19.5 inches, increasing to 29.5 inches by 12 months and 34.4 inches by 2 years old (WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group, 2006).

For the first few days of life, infants typically lose about 5 percent of their body weight as they eliminate waste and get used to feeding. This often goes unnoticed by most parents but can be cause for concern for those who have a smaller infant. This weight loss is temporary, however, and is followed by a rapid period of growth. By the time an infant is 4 months old, it usually doubles in weight, and by one year has tripled its birth weight. By age 2, the weight has quadrupled. The average length at 12 months (one-year-old) typically ranges from 28.5-30.5 inches. The average length at 24 months (two years old) is around 33.2-35.4 inches (CDC, 2010).

Immunizations

Preventing communicable diseases from early infancy is one of the major tasks of the Public Health System in the USA. Infants mouth every single object they find as one of their typical developmental tasks. They learn through their senses and tasting objects stimulates their brain and provides a sensory experience as well as learning.

Infants have much contact with dirty surfaces. They lay on a carpet that most likely has been contaminated by adults walking on it; they mouth keys, rattles, toys, and books; they crawl on the floor; they hold on to furniture to walk, and much more. How do we prevent infants from getting sick? One possible answer is immunizations.

Many decades ago, our society struggled to find vaccines and cures for illnesses such as Polio, whooping cough, and many other medical conditions. A few decades ago, parents started changing their minds on the need to vaccinate children. Some children are not vaccinated for valid medical reasons, but some states allow a child to be unvaccinated because of a parent’s personal or religious beliefs. At least 1 in 14 children is not vaccinated. What is the outcome of not vaccinating children? Some of the preventable illnesses are returning. Fortunately, each vaccinated child stops the transmission of the disease, a phenomenon called herd immunity. Usually, if 90% of the people in a community (a herd) are immunized, no one dies of that disease.

Adolescence

Adolescents experience an overall physical growth spurt in line with the proximodistal principle, meaning that their growth proceeds from the extremities toward the torso. First, the hands grow, then the arms, and finally the torso. The overall physical growth spurt results in 10-11 inches of added height and 50 to 75 pounds of increased weight. The head begins to grow sometime after the feet have gone through their period of growth. Growth of the head is preceded by growth of the ears, nose, and lips. The difference in these patterns of growth results in adolescents appearing awkward and out of proportion. As the torso grows, so do the internal organs. The heart and lungs experience dramatic growth during this period.

During childhood, boys and girls are quite similar in height and weight. However, gender differences become apparent during adolescence. From approximately age ten to fourteen, the average girl is taller, but not heavier, than the average boy. After that, the average boy becomes both taller and heavier, although individual differences are certainly apparent. As adolescents physically mature, weight differences are more noteworthy than height differences. At eighteen years of age, those who are heaviest weigh almost twice as much as the lightest, but the tallest teens are only about 10% taller than the shortest (Seifert, 2012).

Both height and weight can certainly be sensitive issues for some teenagers. Most modern societies, and the teenagers in them, tend to favor relatively short women and tall men, as well as a somewhat thin body build, especially for girls and women. Yet, neither socially preferred height nor thinness is the destiny for most individuals. Being overweight, in particular, has become a common, serious problem in modern society due to the prevalence of diets high in fat and lifestyles low in activity (Tartamella et al., 2004). The educational system has, unfortunately, contributed to the problem as well by gradually restricting the number of physical education classes in the past two decades.

Average height and weight are also related somewhat to racial and ethnic background. In general, children of Asian background tend to be slightly shorter than children of European and North American background. The latter in turn tend to be shorter than children from African societies (Eveleth & Tanner, 1990). Body shape differs slightly as well, though the differences are not always visible until after puberty. Youths from Asian backgrounds tend to have arms and legs that are a bit short relative to their torsos, and African background youth tend to have relatively long arms and legs. The differences are only averages, as there are large individual differences as well.

Adulthood – Physical Changes of Aging

The Baltimore Longitudinal Study on Aging (BLSA) (NIA, 2011) began in 1958 and has traced the aging process in 1,400 people from age 20 to 90. Researchers from the BLSA have found that the aging process varies significantly from individual to individual and from one organ system to another.

However, some key generalizations can be made including:

- Heart muscles thicken with age

- Arteries become less flexible

- Lung capacity diminishes

- Kidneys become less efficient in removing waste from the blood

- Bladder loses its ability to store urine

- Brain cells also lose some functioning, but new neurons can also be produced.

Many of these changes are determined by genetics, lifestyle, and disease.

Body Changes

Everyone’s body shape changes naturally as they age. According to the National Library of Medicine (2014) after age 30 people tend to lose lean tissue, and some of the cells of the muscles, liver, kidney, and other organs are lost. Tissue loss reduces the amount of water in the body and bones may lose some of their minerals and become less dense (a condition called osteopenia in the early stages and osteoporosis in the later stages). The amount of body fat goes up steadily after age 30, and older individuals may have almost one-third more fat compared to when they were younger. Fat tissue builds up toward the center of the body, including around the internal organs.

Skin, Hair, and Nails

With age, skin loses fat, and becomes thinner, less elastic, and no longer looks plump and smooth. Veins and bones can be seen more easily, and scratches, cuts, and bumps can take longer to heal. Years of exposure to the sun may lead to wrinkles, dryness, and cancer. Older people may bruise more easily, and it can take longer for these bruises to heal. Some medicines or illnesses may also cause bruising. Gravity can cause skin to sag and wrinkle, and smoking can wrinkle skin as well. Also, seen in older adulthood are age spots, previously called “liver spots”. They look like flat, brown spots and are often caused by years in the sun. Skin tags are small, usually flesh-colored growths of skin that have a raised surface. They become common as people age, especially for women, but both age spots and skin tags are harmless (NIA, 2015).

With age, skin loses fat, and becomes thinner, less elastic, and no longer looks plump and smooth. Veins and bones can be seen more easily, and scratches, cuts, and bumps can take longer to heal. Years of exposure to the sun may lead to wrinkles, dryness, and cancer. Older people may bruise more easily, and it can take longer for these bruises to heal. Some medicines or illnesses may also cause bruising. Gravity can cause skin to sag and wrinkle, and smoking can wrinkle skin as well. Also, seen in older adulthood are age spots, previously called “liver spots”. They look like flat, brown spots and are often caused by years in the sun. Skin tags are small, usually flesh-colored growths of skin that have a raised surface. They become common as people age, especially for women, but both age spots and skin tags are harmless (NIA, 2015).

Nearly everyone has hair loss as they age, and the rate of hair growth slows down as many hair follicles stop producing new hair (U.S. National Library of Medicine, 2019). The loss of pigment and subsequent graying begin in middle adulthood and continues during late adulthood. The body and face also lose hair. Facial hair may grow coarser. For women, this often occurs around the chin and above the upper lip. For men, the hair of the eyebrows, ears, and nose may grow longer. Nails, particularly toenails, may become hard and thick. Lengthwise ridges may develop in the fingernails and toenails. However, pits, lines, and changes in shape or color of fingernails should be checked by a healthcare provider as they can be related to nutritional deficiencies or kidney disease (U.S. National Library of Medicine, 2019).

Height and Weight

The tendency to become shorter as one ages occurs among all races and sexes. Height loss is related to aging changes in the bones, muscles, and joints. A total of 1 to 3 inches in height is lost with aging. People typically lose almost one-half inch every 10 years after age 40, and height loss is even more rapid after age 70. Changes in body weight vary for men and women. Men often gain weight until about age 55, and then begin to lose weight later in life, possibly related to a drop in the male sex hormone testosterone. Women usually gain weight until age 65 and then begin to lose weight. Weight loss later in life occurs partly because fat replaces lean muscle tissue, and fat weighs less than muscle. Diet and exercise are important factors in weight changes in late adulthood (National Library of Medicine, 2014).

Sarcopenia is the loss of muscle tissue as a natural part of aging. Sarcopenia is most noticeable in men, and physically inactive people can lose as much as 3% to 5% of their muscle mass each decade after age 30, but active people still lose muscle (Webmd, 2016). Symptoms include a loss of stamina and weakness, which can decrease physical activity and subsequently shrink muscles further. Sarcopenia typically increases around age 75, but it may also speed up as early as 65 or as late as 80. Factors involved in sarcopenia include a reduction in nerve cells responsible for sending signals to the muscles from the brain to begin moving, a decrease in the ability to turn protein into energy, and not receiving enough calories or protein to sustain adequate muscle mass. Any loss of muscle is important because it lessens strength and mobility, and sarcopenia is a factor in frailty and the likelihood of falls and fractures in older adults. Maintaining strong leg and heart muscles is important for independence. Weightlifting, walking, swimming, or engaging in other cardiovascular exercises can help strengthen muscles and prevent atrophy.

7.3 Sexual Development and Endocrine System

Sexual Development in Early Childhood

Historically, children have been thought of as innocent or incapable of sexual arousal (Aries, 1962). Yet, the physical dimension of sexual arousal is present from birth. However, to associate the elements of seduction, power, love, or lust that is part of the adult meanings of sexuality would be inappropriate. Sexuality begins in childhood as a response to physical states and sensations and cannot be interpreted as similar to that of adults in any way (Carroll, 2007).

Infancy

Boys and girls are capable of erections and vaginal lubrication even before birth (Martinson, 1981). Arousal can signal overall physical contentment and stimulation that accompanies feeding or warmth. Infants begin to explore their bodies and touch their genitals as soon as they have sufficient motor skills. This stimulation is for comfort or to relieve tension rather than to reach orgasm (Carroll, 2007).

Early Childhood

Self-stimulation is common in early childhood for both boys and girls. Curiosity about the body and about others’ bodies is a natural part of early childhood as well. As children grow, they are more likely to show their genitals to siblings or peers to take off their clothes and touch each other (Okami, Olmstead, & Abramson, 1997). Masturbation is common for both boys and girls. Boys are often shown by other boys how to masturbate, but girls tend to find out accidentally. Additionally, boys masturbate more often and touch themselves more openly than girls (Schwartz, 1999).

Hopefully, parents respond to this without undue alarm and without making the child feel guilty about their bodies. Instead, messages about what is going on and the appropriate time and place for such activities help the child learn what is appropriate.

Puberty and Adolescence

Puberty is a period of rapid growth and sexual maturation. These changes begin sometime between the ages of eight and fourteen. Girls begin puberty at around ten years of age and boys begin approximately two years later. Pubertal changes take around three to four years to complete.

One of the hallmark features of puberty is the development of sexual maturity. Sexual changes are divided into two categories: Primary sexual characteristics and secondary sexual characteristics. Primary sexual characteristics are changes in the reproductive organs. For females, primary characteristics include growth of the uterus and menarche or the first menstrual period. The female gametes, which are stored in the ovaries, are present at birth but are immature. Each ovary contains about 400,000 gametes, but only 500 will become mature eggs (Crooks & Baur, 2007). Beginning at puberty, one ovum ripens and is released about every 28 days during the menstrual cycle. Stress and a higher percentage of body fat can cause menstruation at younger ages. For males, this includes growth of the testes, penis, scrotum, and spermarche or first ejaculation of semen. This occurs between 11 and 15 years of age.

Secondary sexual characteristics are visible physical changes that signal sexual maturity but are not directly linked to reproduction. For females, breast development occurs around age 10, although full development takes several years. Hips broaden, and pubic and underarm hair develops and also becomes darker and coarser. For males, this includes broader shoulders and a lower voice as the larynx grows. Hair becomes coarser and darker, and hair growth occurs in the pubic area, under the arms, and on the face.

Effects of Pubertal Age

The age of puberty is getting younger for children throughout the world, referred to as the secular trend. According to Euling et al. (2008) data are sufficient to suggest a trend toward an earlier breast development onset and menarche in girls. A century ago, the average age of a girl’s first period in the United States and Europe was 16, while today it is around 13. Because there is no clear marker of puberty for boys, it is harder to determine if boys are also maturing earlier. In addition to better nutrition, less positive reasons associated with early puberty for girls include increased stress, obesity, and endocrine-disrupting chemicals.

Cultural differences are noted with African American girls entering puberty at the earliest. Hispanic girls start puberty the second earliest, while European-American girls rank third in their age of starting puberty, and Asian-American girls, on average, develop last. Although African American girls are typically the first to develop, they are less likely to experience negative consequences of early puberty when compared to European-American girls (Weir, 2016).

Research has demonstrated mental health problems linked to children who begin puberty earlier than their peers. For girls, early puberty is associated with depression, substance use, eating disorders, disruptive behavior disorders, and early sexual behavior (Graber, 2013). Early maturing girls demonstrate more anxiety and less confidence in their relationships with family and friends, and they compare themselves more negatively to their peers (Weir, 2016).

Problems with early puberty seem to be due to the mismatch between the child’s appearance and the way she acts and thinks. Adults especially may assume the child is more capable than she actually is, and parents might grant more freedom than the child’s age would indicate. For girls, the emphasis on physical attractiveness and sexuality is emphasized at puberty and they may lack effective coping strategies to deal with the attention they receive, especially from older boys.

Additionally, mental health problems are more likely to occur when the child is among the first in his or her peer group to develop. Because the preadolescent time is one of not wanting to appear different, early developing children stand out among their peer group and gravitate toward those who are older. For girls, this results in them interacting with older peers who engage in risky behaviors such as substance use and early sexual behavior (Weir, 2016).

Boys also see changes in their emotional functioning at puberty. According to Mendle et al. (2010), while most boys experienced a decrease in depressive symptoms during puberty, boys who began puberty earlier and exhibited a rapid tempo, or a fast rate of change, actually increased in depressive symptoms. The effects of pubertal tempo were stronger than those of pubertal timing, suggesting that rapid pubertal change in boys may be a more important risk factor than the timing of development. In a further study to better analyze the reasons for this change, Mendle et al. (2012) found that both early maturing boys and rapidly maturing boys displayed decrements in the quality of their peer relationships as they moved into early adolescence, whereas boys with more typical timing and tempo development experienced improvements in peer relationships. The researchers concluded that the transition in peer relationships may be especially challenging for boys whose pubertal maturation differs significantly from those of others their age. Consequences for boys attaining early puberty were increased odds of cigarette, alcohol, or other drug use (Dudovitz, et al., 2015). However, from the outside, early maturing boys are also often perceived as well-adjusted, popular, and tend to hold leadership positions.

The Climacteric

One biologically based change that occurs during midlife is the climacteric. During midlife, men may experience a reduction in their ability to reproduce. Women, however, lose their ability to reproduce once they reach menopause.

Menopause

Menopause refers to a period of transition in which a woman’s ovaries stop releasing eggs and the level of estrogen and progesterone production decreases. After menopause, a woman’s menstruation ceases (National Institute of Health, 2007).

Changes typically occur between the mid-40s and mid-50s. The median age range for a woman to have her last menstrual period is 50-52, but ages vary. A woman may first begin to notice that her periods are more or less frequent than before. These changes in menstruation may last from 1 to 3 years. After a year without menstruation, a woman is considered post-menopausal and no longer capable of reproduction. (Keep in mind that some women, however, may experience another period even after going for a year without one.) The loss of estrogen also affects vaginal lubrication which diminishes and becomes waterier. The vaginal wall also becomes thinner, and less elastic.

Changes typically occur between the mid-40s and mid-50s. The median age range for a woman to have her last menstrual period is 50-52, but ages vary. A woman may first begin to notice that her periods are more or less frequent than before. These changes in menstruation may last from 1 to 3 years. After a year without menstruation, a woman is considered post-menopausal and no longer capable of reproduction. (Keep in mind that some women, however, may experience another period even after going for a year without one.) The loss of estrogen also affects vaginal lubrication which diminishes and becomes waterier. The vaginal wall also becomes thinner, and less elastic.

Menopause is not seen as universally distressing (Lachman, 2004). Changes in hormone levels are associated with hot flashes and sweats in some women, but women vary in the extent to which these are experienced. Depression, irritability, and weight gain are not necessarily due to menopause (Avis, 1999; Rossi, 2004). Depression and mood swings are more common during menopause in women who have prior histories of these conditions rather than those who have not. The incidence of depression and mood swings is not greater among menopausal women than non-menopausal women.

Cultural influences also play a role in the way menopause is experienced. For example, once after listing the symptoms of menopause in a psychology course, a woman from Kenya responded, “We do not have this in my country or if we do, it is not a big deal,” to which some U.S. students replied, “I want to go there!” Indeed, there are cultural variations in the experience of menopausal symptoms. Hot flashes are experienced by 75 percent of women in Western cultures, but by less than 20 percent of women in Japan (Obermeyer in Berk, 2007).

Women in the United States respond differently to menopause depending upon the expectations they have for themselves and their lives. White, African-American, Mexican-American, and career-oriented women overall tend to think of menopause as a liberating experience. Nevertheless, there has been a popular tendency to erroneously attribute frustrations and irritations expressed by women of menopausal age to menopause and thereby not take her concerns seriously. Fortunately, many practitioners in the United States today are normalizing rather than pathologizing menopause.

Concerns about the effects of hormone replacement have changed the frequency with which estrogen replacement and hormone replacement therapies have been prescribed for menopausal women. Estrogen replacement therapy was once commonly used to treat menopausal symptoms. But more recently, hormone replacement therapy has been associated with breast cancer, stroke, and the development of blood clots (NLM/NIH, 2007). Most women do not have symptoms severe enough to warrant estrogen or hormone replacement therapy (HRT). Women who do require HRT can be treated with lower doses of estrogen and monitored with more frequent breast and pelvic exams. There are also some other ways to reduce symptoms. These include avoiding caffeine and alcohol, eating soy, remaining sexually active, practicing relaxation techniques, and using water-based lubricants during intercourse.

Fifty million women in the USA aged 50-55 are post-menopausal. During and after menopause a majority of women will experience weight gain. Changes in estrogen levels lead to a redistribution of body fat from the hips and back to the stomach. This is more dangerous to general health and well-being because abdominal fat is largely visceral, meaning it is contained within the abdominal cavity and may not look like typical weight gain. That is, it accumulates in the space between the liver, intestines, and other vital organs. This is far more harmful to health than subcutaneous fat which is the kind of fat located under the skin. It is possible to be relatively thin and retain a high level of visceral fat, yet this type of fat is deemed especially harmful by medical research.

Andropause

Do males experience a climacteric? Yes. While they do not lose their ability to reproduce as they age, they do tend to produce lower levels of testosterone and fewer sperm. However, men are capable of reproduction throughout life after puberty. It is natural for sex drive to diminish slightly as men age, but a lack of sex drive may be a result of extremely low levels of testosterone. About 5 million men experience low levels of testosterone that result in symptoms such as a loss of interest in sex, loss of body hair, difficulty achieving or maintaining erection, loss of muscle mass, and breast enlargement. This decrease in libido and lower testosterone (androgen) levels is known as andropause, although this term is somewhat controversial as this experience is not delineated, as menopause is for women. Low testosterone levels may be due to glandular diseases such as testicular cancer. Testosterone levels can be assessed and if they are low, men can be treated with testosterone replacement therapy. This can increase sex drive, muscle mass, and beard growth. However, long-term HRT for men can increase the risk of prostate cancer (The Patient Education Institute, 2005).

The debate around declining testosterone levels in men may hide a fundamental fact. The issue is not about individual males experiencing individual hormonal changes at all. We have all seen the adverts on the media promoting substances to boost testosterone: “Is it low-T?” The answer is probably in the affirmative, if somewhat relative. That is, in all likelihood, they will have lower testosterone levels than their fathers. However, it is equally likely that the issue does not lie solely in their physiological makeup but is rather a generational transformation (Travison et al, 2007). Why this has occurred in such a dramatic fashion is still unknown. There is evidence that low testosterone may have negative health effects on men. In addition, some studies show evidence of rapidly decreasing sperm count and grip strength. Exactly why these changes are happening is unknown and will likely involve more than one cause.[1]

The Climacteric and Sexuality

Sexuality is an important part of people’s lives at any age. Midlife adults tend to have sex lives that are very similar to that of younger adults. And many women feel freer and less inhibited sexually as they age. However, a woman may notice less vaginal lubrication during arousal and men may experience changes in their erections from time to time. This is particularly true for men after age 65. Men who experience consistent problems are likely to have other medical conditions (such as diabetes or heart disease) that impact sexual functioning (National Institute on Aging, 2005).

Couples continue to enjoy physical intimacy and may engage in more foreplay, oral sex, and other forms of sexual expression rather than focusing as much on sexual intercourse. The risk of pregnancy continues until a woman has been without menstruation for at least 12 months, however, couples should continue to use contraception. People continue to be at risk of contracting sexually transmitted infections such as genital herpes, chlamydia, and genital warts. About ten percent of new HIV diagnoses in the United States are in people 55 and older.[2] Of all people living with HIV, almost 50% are aged 50 or over. [3] Getting tested is important- even people who are not high-risk can be impacted. Also, practicing safe sex is important at any age- safe sex is not just about avoiding an unwanted pregnancy; it is about protecting yourself from STDs as well. Hopefully, when partners understand how aging affects sexual expression, they will be less likely to misinterpret these changes as a lack of sexual interest or displeasure in the partner and be more able to continue to have satisfying and safe sexual relationships.

Women and Aging

In Western society, aging for women is much more stressful than for men as society emphasizes youthful beauty and attractiveness (Slevin, 2010). The description that aging men are viewed as “distinguished” and aging women are viewed as “old” is referred to as the double standard of aging (Teuscher & Teuscher, 2006). Since women have traditionally been valued for their reproductive capabilities, they may be considered old once they are post-menopausal. In contrast, men have traditionally been valued for their achievements, competence, and power, and therefore are not considered old until decades later when they are physically unable to work (Carroll, 2016). Consequently, women experience more fear, anxiety, and concern about their identity as they age, and may feel pressure to prove themselves as productive and valuable members of society (Bromberger et al., 2013).

In Western society, aging for women is much more stressful than for men as society emphasizes youthful beauty and attractiveness (Slevin, 2010). The description that aging men are viewed as “distinguished” and aging women are viewed as “old” is referred to as the double standard of aging (Teuscher & Teuscher, 2006). Since women have traditionally been valued for their reproductive capabilities, they may be considered old once they are post-menopausal. In contrast, men have traditionally been valued for their achievements, competence, and power, and therefore are not considered old until decades later when they are physically unable to work (Carroll, 2016). Consequently, women experience more fear, anxiety, and concern about their identity as they age, and may feel pressure to prove themselves as productive and valuable members of society (Bromberger et al., 2013).

Attitudes about aging, however, do vary by race, culture, and sexual orientation. In some cultures, aging women gain greater social status. For example, as Asian women age, they attain greater respect and have greater authority in the household (Fung, 2013). Compared to white women, Black and Latina women possess fewer stereotypes about aging (Schuler et al., 2008). Lesbians are also more positive about aging and looking older than heterosexual women (Slevin, 2010). The impact of media certainly plays a role in how women view aging by selling anti-aging products and supporting cosmetic surgeries to look younger (Gilleard & Higgs, 2000).

Attitudes about aging, however, do vary by race, culture, and sexual orientation. In some cultures, aging women gain greater social status. For example, as Asian women age, they attain greater respect and have greater authority in the household (Fung, 2013). Compared to white women, Black and Latina women possess fewer stereotypes about aging (Schuler et al., 2008). Lesbians are also more positive about aging and looking older than heterosexual women (Slevin, 2010). The impact of media certainly plays a role in how women view aging by selling anti-aging products and supporting cosmetic surgeries to look younger (Gilleard & Higgs, 2000).

7.4 Late Adulthood in the United States

Late adulthood, which includes those aged 65 years and above, is the fastest-growing age division of the United States population (Gatz et al., 2016). Currently, one in seven Americans is 65 years of age or older. The first of the baby boomers (born from 1946-1964) turned 65 in 2011, and approximately 10,000 baby boomers turn 65 every day. By the year 2050, almost one in four Americans will be over 65, and will be expected to live longer than previous generations. According to the U. S. Census Bureau (2014b) a person who turned 65 in 2015 can expect to live another 19 years, which is 5.5 years longer than someone who turned 65 in 1950. This increasingly aged population has been referred to as the “Graying of America”. This “graying” is already having significant effects on the nation in many areas, including work, health care, housing, social security, caregiving, and adaptive technologies. The table below shows the 2012, 2020, and 2030 projected percentages of the U.S. population ages 65 and older.

The "Graying of the World"

| Percent of the World Population 65 yrs. and Older | 2012 | 2020 | 2030 |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 13.7% | 20.3% | 22% |

| Japan | 24% | 32.2% | 40% |

| Germany | 20% | 27.9% | 30% |

| Canada | 16.5% | 25% | 26.5% |

| Russia | 13% | 20% | 26% |

The table above is adapted from Lally & Valentine-French (2019) and compiled from data from An Aging Nation: The older population in the United States. United States Census Bureau.https://www.census.gov/prod/2014pubs/p25-1140.pdf

The “Graying” of the World

Even though the United States is aging, it is still younger than most other developed countries (Ortman, Velkoff, & Hogan, 2014). Germany, Italy, and Japan all had at least 20% of their population aged 65 and over in 2012, and Japan had the highest percentage of elderly. Additionally, between 2012 and 2050, the proportion aged 65 and over is projected to increase in all developed countries. Japan is projected to continue to have the oldest population in 2030 and 2050. The table below shows the percentages of citizens aged 65 and older in select developed countries in 2012 and projected for 2030 and 2050.

Percent of U.S. Population in Late Adulthood

| Age Cohort | 2012 | 2020 | 2030 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 65-69 yrs. | 4.5% | 5.4% | 5.6% |

| 70-74 yrs. | 3.2% | 4.4% | 5.2% |

| 75-79 yrs. | 2.4% | 3.0% | 4.1% |

| 80-84 yrs. | 1.8% | 1.9% | 2.9% |

| 85+ yrs. | 1.9% | 2.0% | 2.5% |

Adapted from Lally & Valentine-French (2019) and compiled from data from An Aging Nation: The Older Population in the United States. United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/prod/2014pubs/p25-1140.pdf

According to the National Institute on Aging (NIA, 2015b), there are 524 million people over 65 worldwide. This number is expected to increase from 8% to 16% of the global population by 2050. Between 2010 and 2050, the number of older people in less developed countries is projected to increase by more than 250%, compared with only a 71% increase in developed countries. Declines in fertility and improvements in longevity account for the percentage increase for those 65 years and older. In more developed countries, fertility fell below the replacement rate of two live births per woman by the 1970s, down from nearly three children per woman around 1950. Fertility rates also fell in many less developed countries from an average of six children in 1950 to an average of two or three children in 2005. In 2006, fertility was at or below the two-child replacement level in 44 less-developed countries (NIA, 2015d).

In total number, the United States is projected to have a larger older population than the other developed nations, but a smaller older population compared with China and India, the world’s two most populous nations (Ortman et al., 2014). By 2050, China’s older population is projected to grow larger than the total U.S. population today. As the population ages, concerns grow about who will provide for those requiring long-term care. In 2000, there were about 10 people 85 and older for every 100 persons between ages 50 and 64. These midlife adults are the most likely care providers for their aging parents. The number of old requiring support from their children is expected to more than double by the year 2040 (He, Sengupta, Velkoff, & DeBarros, 2005). These families will certainly need external physical, emotional, and financial support to meet this challenge.

Age Cohorts During Late Adulthood

Late adulthood encompasses a long period, from age 60 potentially to age 120 – 60 years! Researchers recognize that within that time period, from age 60 until death, there are multiple ages or sub-periods, that can be distinguished based on differences in peoples’ typical physical health and mental functioning during those age periods. In the chart below, review the four age cohorts and their characteristics found in late adulthood.

Late Adulthood Cohorts and Characteristics

| Cohort | Ages | Description/Characteristics of Cohort |

|---|---|---|

| Young-Old | 65-74 |

|

| Old-Old | 75-84 |

|

| Oldest-Old | 85-99 |

|

| Centenarians | 100+ |

|

Information provided in chart from Lally & Valentine-French, 2022

Now, you must be wondering, who has lived the longest? According to Guinness World Records (2016), Jeanne Louise Calment (France) has been documented to be the longest-living person at 122 years and 164 days old! Wow!

7.5 Theories of Aging

Each person experiences age-related physical changes based on many factors: biological factors, such as molecular and cellular changes, and oxidative damage are called primary aging, while aging that occurs due to controllable factors, such as an unhealthy lifestyle including lack of physical exercise and poor diet, is called secondary aging (Busse, 1969).

Getting out of shape is not an inevitable part of aging; it is probably because middle-aged adults become less physically active and experience greater stress. Smoking tobacco, drinking alcohol, poor diet, stress, physical inactivity, and chronic disease, such as diabetes or arthritis, reduce overall health. However, some things can be done to combat many of these changes by adopting healthier lifestyles.

Why do we age? Many theories attempt to explain how humans age, however, researchers still do not fully understand what factors contribute to the human lifespan (Jin, 2010). Research on aging is constantly evolving and includes a variety of studies involving genetics, biochemistry, animal models, and human longitudinal studies (NIA, 2011a). According to Jin (2010), modern biological theories of human aging involve two categories. The first is Programmed Theories that follow a biological timetable, possibly a continuation of childhood development. This timetable would depend on “changes in gene expression that affect the systems responsible for maintenance, repair, and defense responses,” (p. 72). The second category includes Damage or Error Theories which emphasize environmental factors that cause cumulative damage in organisms. Examples from each of these categories will be discussed.

- Genetics – One’s genetic makeup certainly plays a role in longevity, but scientists are still attempting to identify which genes are responsible. Based on animal models, some genes promote longer life, while other genes limit longevity. Specifically, longevity may be due to genes that better equip someone to survive a disease. For others, some genes may accelerate the rate of aging, while others decrease the rate. To help determine which genes promote longevity and how they operate, researchers scan the entire genome and compare genetic variants in those who live longer with those who have an average or shorter lifespan. For example, a National Institutes of Health study identified genes possibly associated with blood fat levels and cholesterol, both risk factors for coronary disease and early death (NIA, 2011a). Researchers believe that it is most likely a combination of many genes that affect the rate of aging.

- Evolutionary Theory – Evolutionary psychology emphasizes the importance of natural selection; that is, those genes that allow one to survive and reproduce will be more likely to be transmitted to offspring. Genes associated with aging, such as Alzheimer Disease, do not appear until after the individual has passed their main reproductive years. Consequently, natural selection has not eliminated these damaging disorders from the gene pool. If these detrimental disorders occurred earlier in the development cycle, they may have been eliminated already (Gems, 2014).

Cellular Clock Theory – This theory suggests that biological aging is due to the fact that normal cells cannot divide indefinitely. This is known as the Hayflick limit, and is evidenced in cells studied in test tubes, which divide about 40-60 times before they stop (Bartlett, 2014). But what is the mechanism behind this cellular senescence? At the end of each chromosome’s strand is a sequence of DNA that does not code for any particular protein, but protects the rest of the chromosome, which is called a telomere. With each replication, the telomere gets shorter. Once it becomes too short the cell does one of three things. It can stop replicating by turning itself off, called cellular senescence. It can stop replicating by dying, called apoptosis. Or, as in the development of cancer, it can continue to divide and become abnormal. Senescent cells can also create problems. While they may be turned off, they are not dead, thus they still interact with other cells in the body and can lead to an increased risk of disease. When we are young, senescent cells may reduce our risk of serious diseases such as cancer, but as we age, they increase our risk of such problems (NIA, 2011a). Understanding why cellular senescence changes from being beneficial to being detrimental is still under investigation. The answer may lead to some important clues about the aging process.

Cellular Clock Theory – This theory suggests that biological aging is due to the fact that normal cells cannot divide indefinitely. This is known as the Hayflick limit, and is evidenced in cells studied in test tubes, which divide about 40-60 times before they stop (Bartlett, 2014). But what is the mechanism behind this cellular senescence? At the end of each chromosome’s strand is a sequence of DNA that does not code for any particular protein, but protects the rest of the chromosome, which is called a telomere. With each replication, the telomere gets shorter. Once it becomes too short the cell does one of three things. It can stop replicating by turning itself off, called cellular senescence. It can stop replicating by dying, called apoptosis. Or, as in the development of cancer, it can continue to divide and become abnormal. Senescent cells can also create problems. While they may be turned off, they are not dead, thus they still interact with other cells in the body and can lead to an increased risk of disease. When we are young, senescent cells may reduce our risk of serious diseases such as cancer, but as we age, they increase our risk of such problems (NIA, 2011a). Understanding why cellular senescence changes from being beneficial to being detrimental is still under investigation. The answer may lead to some important clues about the aging process.- DNA Damage – Over time DNA, which contains the genetic code for all organisms, accumulates damage. This is usually not a concern as our cells are capable of repairing damage throughout our life. Further, some damage is harmless. However, some damage cannot be repaired and remains in our DNA. Scientists believe that this damage, and the body’s inability to fix itself, is an important part of aging (NIA, 2011a). As DNA damage accumulates with increasing age, it can cause cells to deteriorate and malfunction (Jin, 2010). Factors that can damage DNA include ultraviolet radiation, cigarette smoking, and exposure to hydrocarbons, such as auto exhaust and coal (Dollemore, 2006).

- Mitochondrial Damage – Damage to mitochondrial DNA can lead to a decaying of the mitochondria, which is a cell organelle that uses oxygen to produce energy from food. The mitochondria convert oxygen to adenosine triphosphate (ATP) which provides the energy for the cell. When damaged, mitochondria become less efficient and generate less energy for the cell which can lead to cellular death (NIA, 2011a).

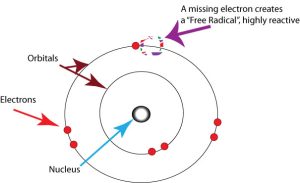

-

A free oxygen radical is an oxygen atom that, having lost an electron, becomes extremely reactive. Free Radicals – When the mitochondria use oxygen to produce energy, they also produce potentially harmful byproducts called oxygen free radicals (NIA, 2011a). The free radicals are missing an electron and create instability in surrounding molecules by taking electrons from them. There is a snowball effect (A takes from B and then B takes from C, etc.) that creates more free radicals which disrupt the cell and cause it to behave abnormally. Some free radicals are helpful as they can destroy bacteria and other harmful organisms, but for the most part, they cause damage in our cells and tissue. Free radicals are identified with disorders seen in those of advanced age, including cancer, atherosclerosis, cataracts, and neurodegeneration. Some research has supported adding antioxidants to our diets to counter the effects of free radical damage because the antioxidants can donate an electron that can neutralize damaged molecules. However, the research on the effectiveness of antioxidants is not conclusive (Harvard School of Public Health, 2016).

- Immune and Hormonal Stress Theories – Ever notice how quickly U.S. presidents seem to age? Before and after photos reveal how stress can play a role in the aging process. When gerontologists study stress, they are not just considering major life events, such as unemployment, the death of a loved one, or the birth of a child. They also include metabolic stress, the life-sustaining activities of the body, such as circulating the blood, eliminating waste, controlling body temperature, and neuronal firing in the brain. In other words, all the activities that keep the body alive also create biological stress.To understand how this stress affects aging, researchers note that both problems with the innate and adaptive immune systems play a key role. The innate immune system is made up of the skin, mucous membranes, cough reflex, stomach acid, and specialized cells that alert the body of an impending threat. With age these cells lose their ability to communicate effectively, making it harder for the body to mobilize its defenses. The adaptive immune system includes the tonsils, spleen, bone marrow, thymus, circulatory system, and lymphatic system that work to produce and transport T cells. T-cells, or lymphocytes, fight bacteria, viruses, and other foreign threats to the body. T-cells are in a “naïve” state before they are programmed to fight an invader and become “memory cells”. These cells now remember how to fight a certain infection should the body ever come across this invader again. Memory cells can remain in your body for many decades, and why the measles vaccine you received as a child is still protecting you from this virus today. As older adults produce fewer new T-cells to be programmed, they are less able to fight off new threats and new vaccines work less effectively. The reason why the shingles vaccine works well with older adults is because they already have some existing memory cells against the varicella virus. The shingles vaccine is acting as a booster (NIA, 2011a).

To understand how this stress affects aging, researchers note that both problems with the innate and adaptive immune systems play a key role. The innate immune system is made up of the skin, mucous membranes, cough reflex, stomach acid, and specialized cells that alert the body of an impending threat. With age these cells lose their ability to communicate effectively, making it harder for the body to mobilize its defenses. The adaptive immune system includes the tonsils, spleen, bone marrow, thymus, circulatory system, and lymphatic system that work to produce and transport T cells. T-cells, or lymphocytes, fight bacteria, viruses, and other foreign threats to the body. T-cells are in a “naïve” state before they are programmed to fight an invader and become “memory cells”. These cells now remember how to fight a certain infection should the body ever come across this invader again. Memory cells can remain in your body for many decades, and why the measles vaccine you received as a child is still protecting you from this virus today. As older adults produce fewer new T-cells to be programmed, they are less able to fight off new threats and new vaccines work less effectively. The reason why the shingles vaccine works well with older adults is because they already have some existing memory cells against the varicella virus. The shingles vaccine is acting as a booster (NIA, 2011a). - Hormonal Stress Theory, also known as Neuroendocrine Theory of Aging, suggests that as we age the ability of the hypothalamus to regulate hormones in the body begins to decline leading to metabolic problems (American Federation of Aging Research (AFAR) 2011). This decline is linked to excess of the stress hormone cortisol. While many of the body’s hormones decrease with age, cortisol does not (NIH, 2014a). The more stress we experience, the more cortisol released, and the more hypothalamic damage that occurs. Changes in hormones have been linked to several metabolic and hormone-related problems that increase with age, such as diabetes (AFAR, 2011), thyroid problems (NIH, 2013), osteoporosis, and orthostatic hypotension (NIH, 2014a).

References

Berk, L. (2007). Development through the lifespan (4th ed.) (pp 137). Pearson Education.

Bromberger, J. T., Kravitz, H. M., Chang, Y., Randolph Jr, J. F., Avis, N. E., Gold, E. B., & Matthews, K.A. (2013). Does risk for anxiety increase during the menopausal transition? Study of women’s health across the nation (SWAN). Menopause, 20(5), 488.

Carroll, J. L. (2007). Sexuality now: Embracing diversity (2nd ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Learning.

Carroll, J. L. (2016). Sexuality now: Embracing diversity. Cengage Learning.

Crooks, K. L., & Baur, K. (2007). Our sexuality (10th ed.). Wadsworth.

Dollemore, D. (2006, August 29). Publications. National Institute on Aging. http://www.nia.nih.gov/HealthInformation/Publications?AgingUndertheMicroscope/

Dudovitz, R. N., Chung, P. J., Elliott, M. N., Davies, S. L., Tortolero, S., Baumler, E., … & Schuster, M.A. (2015). Peer Reviewed: Relationship of age for grade and pubertal stage to early initiation of substance use. Preventing chronic disease, 12.

Eisenberg, A., Murkoff, H. E., & Hathaway, S. E. (1989). What to expect the first year. Workman Publishing.

Euling, S. Y., Herman-Giddens, M.E., Lee, P.A., Selevan, S. G., Juul, A., Sorensen, T. I., Dunkel, L., Himes, J.H., Teilmann, G., & Swan, S.H. (2008). Examination of US puberty-timing data from 1940 to 1994 for secular trends: Panel findings. Pediatrics, 121, S172-91. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1813D.

Eveleth, P. & Tanner, J. (1990). Worldwide variation in human growth (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press.

Fung, H. H. (2013). Aging in culture. The Gerontologist, 53(3), 369-377.

Gilleard, C., & Higgs, P. (2000). Cultures of aging: Self, citizen and the body. Prentice Hall Publishers.

Gems, D. (2014). Evolution of sexually dimorphic longevity in humans. Aging, 6, 84-91.

Graber, J. A. (2013). Pubertal timing and the development of psychopathology in adolescence and beyond. Hormones and Behavior, 64, 262-289.

Harvard School of Public Health. (2016). Antioxidants: Beyond the hype. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/antioxidants

Jin, K. (2010). Modern biological theories of aging. Aging and Disease, 1, 72-74.

Mendle, J., Harden, K. P., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Graber, J. A. (2010). Development’s tortoise and hare: Pubertal timing, pubertal tempo, and depressive symptoms in boys and girls. Developmental Psychology, 46, 1341–1353.

Mendle, J., Harden, K. P., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Graber, J. A. (2012). Peer relationships and depressive symptomatology in boys at puberty. Developmental Psychology, 48(2), 429–435.

National Institute on Aging. (2011). Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging Home Page. http://www.grc.nia.nih.gov/branches/blsa/blsa.htm

National Institute on Aging. (2011a). Biology of aging: Research today for a healthier tomorrow. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/publication/biology-aging/preface

National Institute on Aging. (2015). Skin care and aging. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/publication/skin-care– and-aging

National Institutes of Health. (2014a). Aging changes in hormone production. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/004000.htm

National Library of Medicine. (2014). Aging changes in body shape. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/003998.htm

National Institutes of Health. (2007). Menopause: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000894.htm

Rauh, Sherry (n.d.). Is your baby on track? WebMD. https://www.webmd.com/parenting/baby/features/is-your-baby-on-track#1.

Seifert, K. (2012). Educational psychology. http://cnx.org/content/col11302/1.2

Schuler, P. B., Vinci, D., Isosaari, R. M., Philipp, S. F., Todorovich, J., Roy, J. L., & Evans, R. R. (2008). Body-shape perceptions and body mass index of older African American and European American women. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 23, 255-264.

Slevin, K. F. (2010). If I had lots of money… I’d have a body makeover: Managing the aging body. Social Forces, 88(3), 1003-1020.

Smith, J. (2000). The fourth age: A period of psychological mortality? Max Planck Forum, 4, 75-88.

Tartamella, L., Herscher, E., & Woolston, C. (2004). Generation extra large. Basic Books.

Teuscher, U., & Teuscher, C. (2007). Reconsidering the double standard of aging: Effects of gender and sexual orientation on facial attractiveness ratings. Personality and Individual Differences, 42(4), 631-639.

United States National Library of Medicine. (2019). Aging changes in hair and nails. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/004005.htm

Volpi, E., Nazemi, R., & Fujita, S. (2004). Muscle tissue changes with aging. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care, 7(4), 405-10. ↵

Webmd. (2016). Sarcopenia with aging. http://www.webmd.com/healthy- aging/sarcopenia-with-aging

Weir, K. (2016). The risks of earlier puberty. Monitor on Psychology, 47(3), 41-44.

World Health Organization. (2006). Child growth standards. https://www.who.int/tools/child-growth-standards/who-multicentre-growth-reference-study

Media Attributions

- nine-koepfer-1xkBxEfBS_I-unsplash © Photo by nine koepfer

- family-1111818_1280 © mario0107 is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- child-with-dog-4297149_1920 © TheOtherKev is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- swimming-2561560_1280 © StockSnap is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- elderly-3628304_1280 © https://pixabay.com/users/nikon-2110-8762482/ is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- elderly-1559369_640 © legabbiedelcuore

- vendors-3555692_1280 © Bonsens-Tono is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- JeanneCalmentaged20 © Unknown is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Wooden_hourglass_3 © S Sepp

- Free-radicals-oxygen © Healthvalue is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license