4 Choosing a Communication Channel

Learning Objectives

Upon completing this chapter, you should be able to:

- categorize specific elements of a given communication scenario as verbal, non-verbal, written, and/or digital;

- determine, based on the richness of the communication, if the appropriate communication channel was implemented for a given communication scenario;

- recommend the most appropriate channel(s) for a given communication scenario.

Topics

- Principle communication channels

- Information richness

- Internal communication channels

- External communication channels

Introduction

The channel or medium used to communicate a message affects how the audience will receive the message. Communication channels can refer to the methods we use to communicate as well as the specific tools we use in the communication process. In this chapter we will define communication channels as a medium for communication, or the passage of information. In this chapter we will discuss the principal channels of communication, as well as the tools commonly used in professional communication. We will discuss the pros, cons, and use cases for each tool and channel, because, in a professional context, the decision about which channel to use can be a critical one.

Communication Channels

Communication channels can be categorized into three principal channels: (1) verbal, (2) written, and (3) non-verbal. Each of these communications channels have different strengths and weaknesses, and oftentimes we can use more than one channel at the same time.

Verbal Communication

Most often when we think of communication, we might imagine two or more people speaking to each other. This is the largest aspect of verbal communication: speaking and listening. The source uses words to code the information and speaks to the receiver, who then decodes the words for understanding and meaning. One example of interference in this channel is choice of words. If the source uses words that are unfamiliar to the receiver, there is a chance they will miscommunicate the message or not communicate at all. The formality of vocabulary choice is another aspect of the verbal channel. In situations with friends or close co-workers, for example, you may choose more casual words, in contrast to words you would choose for a presentation you are making to your supervisors. In the workplace the primary channel of communication is verbal, much of this communication being used to coordinate with others, problem solve, and build collegiality.

Tone

One element of verbal communication is tone. A different tone can change the perceived meaning of a message. Table 1.3.1, “Don’t Use That Tone with Me!” demonstrates just how true that is. If we simply read these words without the added emphasis, we would be left to wonder, but the emphasis shows us how the tone conveys a great deal of information. Now you can see how changing one’s tone of voice can incite or defuse a misunderstanding.

| Placement of Emphasis | Meaning |

|---|---|

| I did not tell John you were late. | Someone else told John you were late. |

| I did not tell John you were late. | This did not happen. |

| I did not tell John you were late. | I may have implied it. |

| I did not tell John you were late. | But maybe I told Sharon and Jose. |

| I did not tell John you were late. | I was talking about someone else. |

| I did not tell John you were late. | I told him you still are late. |

| I did not tell John you were late. | I told him you were attending another meeting. |

Non-Verbal Communication

What you say is a vital part of any communication, but what you don’t say can be even more important. Research also shows that 55 percent of in-person communication comes from non-verbal cues, such as facial expressions, body stance, and smell. According to one study, only 7 percent of a receiver’s comprehension of a message is based on the sender’s actual words; 38 percent is based on paralanguage (the tone, pace, and volume of speech), and 55 percent is based on non-verbal cues such as body language (Mehrabian, 1981).

Research shows that non-verbal cues can also affect whether you get a job offer. Judges examining videotapes of actual applicants were able to assess the social skills of job candidates with the sound turned off. They watched the rate of gesturing, time spent talking, and formality of dress to determine which candidates would be the most successful socially on the job (Gifford, Ng, and Wilkinson, 1985). For this reason, it is important to consider how we appear in the professional environment as well as what we say. Our facial muscles convey our emotions. We can send a silent message without saying a word. A change in facial expression can change our emotional state. Before an interview, for example, if we focus on feeling confident, our face will convey that confidence to an interviewer. Adopting a smile (even if we are feeling stressed) can reduce the body’s stress levels.

Body Language

Generally speaking, simplicity, directness, and warmth convey sincerity, and sincerity is key to effective communication. A firm handshake given with a warm, dry hand is a great way to establish trust. A weak, clammy handshake conveys a lack of trustworthiness. Gnawing one’s lip conveys uncertainty. A direct smile conveys confidence. All of this is true across North America. However, in other cultures the same firm handshake may be considered aggressive and untrustworthy. It helps to be mindful of cultural context when interpreting or using body language.

Smell

Smell is an often overlooked but powerful non-verbal communication method. Take the real estate agent who sprinkles cinnamon in boiling water to mimic the smell of baked goods in her homes, for example. She aims to increase her sales by using a smell to create a positive emotional response that invokes a warm, homelike atmosphere for her clients. As easy as it is for a smell to make someone feel welcome, the same smell may be a complete turnoff to someone else. Some offices and workplaces in North America ban the use of colognes, perfumes, or other fragrances to aim for a scent-free work environment (some people are allergic to such fragrances). It is important to be mindful that using a strong smell of any kind may have an uncertain effect, depending on the people, culture, and other environmental norms.

Eye Contact

In business, the style and duration of eye contact people consider appropriate varies greatly across cultures. In the Canadian culture, looking someone in the eye (for about a second) is considered a sign of trustworthiness. However, in other countries, eye is perceived differently. For instance, in Asian culture, eye contact can be seen as insubordinate e.g., between student and teacher.

Facial Expressions

The human face can produce thousands of different expressions. Experts have decoded these expressions as corresponding to hundreds of different emotional states (Ekman, Friesen, and Hager, 2008). Our faces convey basic information to the outside world. Happiness is associated with an upturned mouth and slightly closed eyes; fear, with an open mouth and wide-eyed stare. Flitting (“shifty”) eyes and pursed lips convey a lack of trustworthiness. The effect facial expressions have on conversation is instantaneous. Our brains may register them as “a feeling” about someone’s character.

Posture

The position of our body relative to a chair or another person is another powerful silent messenger that conveys interest, aloofness, professionalism—or lack thereof. Head up, back straight (but not rigid) implies an upright character. In interview situations, experts advise mirroring an interviewer’s tendency to lean in and settle back in her seat. The subtle repetition of the other person’s posture conveys that we are listening and responding.

Written

In contrast to verbal communications, written professional communications are textual messages. Examples of written communications include memos, proposals, emails, letters, training manuals, and operating policies. They may be printed on paper, handwritten, or appear on the screen. Normally, a verbal communication takes place in real time. Written communication, by contrast, can be constructed over a longer period of time. Written communication is often asynchronous (occurring at different times). That is, the sender can write a message that the receiver can read at any time, unlike a conversation that transpires in real time. There are exceptions, however; for example, a voicemail is a verbal message that is asynchronous. Many jobs involve some degree of writing. Luckily, it is possible to learn to write clearly (more on this in the Plain Language chapter and the writing module).

Digital Communication Channels

The three principal communication channels can be used “in the flesh” and in digital formats. Digital channels extend from face-to-face to video conferencing, from written memos to emails, and from speaking in person to using telephones. The digital channels retain many of the characteristics of the principal channels but influence different aspects of each channel in new ways. The choice between analog and digital can affect the environment, context, and interference factors in the communication process.

Check Your Understanding

Information Richness

Information richness refers to the amount of sensory input available during a communication. For example, speaking to a colleague in a monotone voice with no change in pacing or gestures does not make for a very rich experience. On the other hand, if you use gestures, tone of voice, pace of speech, etc., to communicate meaning beyond the words themselves, you facilitate a richer communication. Channels vary in their information richness. Information-rich channels convey more non-verbal information. For example, a face-to-face conversation is richer than a phone call, but a phone call is richer than an email. Research shows that effective managers tend to use more information-rich communication channels than do less effective managers (Allen and Griffeth, 1997; Fulk and Body, 1991; Yates and Orlikowski, 1992). The figure below illustrates the information richness of different information channels.

| Channel | Information Richness |

|---|---|

| Face-to-face conversation | High |

| Videoconferencing | High |

| Telephone | High |

| Medium | |

| Mobile devices | Medium |

| Blogs | Medium |

| Letter | Medium |

| Written documents | Low |

| Spreadsheets | Low |

Like face-to-face and telephone conversation, videoconferencing has high information richness because receivers and senders can see or hear beyond just the words—they can see the sender’s body language or hear the tone of their voice. Mobile devices, blogs, letters, and memos offer medium-rich channels because they convey words and images. Formal written documents, such as legal documents and spreadsheets (e.g., the division’s budget), convey the least richness, because the format is often rigid and standardized. As a result, nuance is lost.

When determining whether to communicate verbally or in writing, ask yourself, Do I want to convey facts or feelings? Verbal communications are a better way to convey feelings, while written communications do a better job of conveying facts.

Picture a manager delivering a speech to a team of 20 employees. The manager is speaking at a normal pace. The employees appear interested. But how much information is the manager transmitting? Not as much as the speaker believes! Humans listen much faster than they speak.

The average public speaker communicates at a speed of about 125 words per minute. That pace sounds fine to the audience, but faster speech would sound strange. To put that figure in perspective, someone having an excited conversation speaks at about 150 words per minute. Based on these numbers, we could assume that the employees have more than enough time to take in each word the manager delivers. But that is the problem. The average person in the audience can hear 400–500 words per minute (Leed and Hatesohl, 2008). The audience has more time than they need. As a result, they will each be processing many thoughts of their own, on totally different subjects, while the manager is speaking. As this example demonstrates, verbal communication is an inherently flawed medium for conveying specific facts. Listeners’ minds wander. Once we understand this fact, we can make more intelligent communication choices based on the kind of information we want to convey.

The key to effective communication is to match the communication channel with the goal of the message (Barry and Fulmer, 2004). Written media is a better choice when the sender wants a record of the content, has less urgency for a response, is physically separated from the receiver, does not require much feedback from the receiver, or when the message is complicated and may take some time to understand.

Verbal communication makes more sense when the sender is conveying a sensitive or emotional message, needs feedback immediately, and does not need a permanent record of the conversation. Use the guide provided for deciding when to use written versus verbal communication.

| Use Written | Use Verbal |

|---|---|

| to convey facts | to convey emotions |

| to provide a permanent record | when you do not need a permanent record |

| when you do not need a timely response | when the matter is urgent |

| when you do not need immediate feedback | when you need immediate feedback |

| to explain complicated ideas | for simple, easy-to-explain ideas |

Direction of Communication Within Organizations

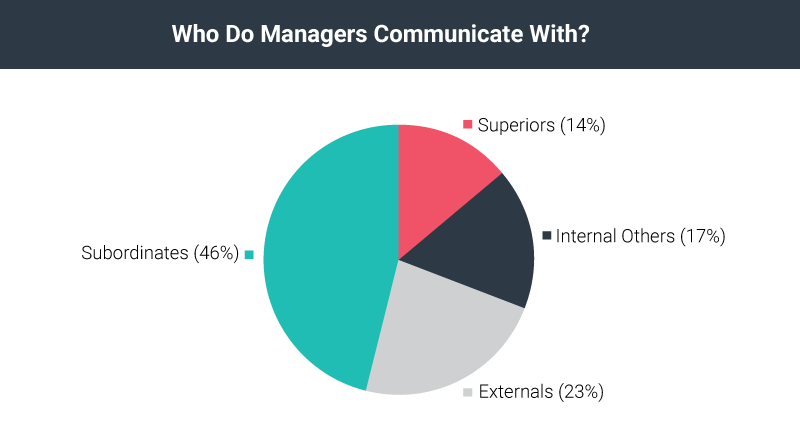

Information can move sideways, from a sender to a receiver—for example, from you to your colleague. It can also move upward, such as to a superior; or downward, such as from management to subordinates.

The status of the sender can affect the receiver’s attentiveness to the message. For example, a senior manager sends a memo to a production supervisor. The supervisor, who has a lower status within the organization, will likely pay close attention to the message. But the same information conveyed in the opposite direction might not get the same attention. The message would be filtered by the senior manager’s perception of priorities and urgencies.

Requests are just one kind of communication in a professional environment. Other communications, both verbal or written, may seek, give, or exchange information. Research shows that frequent communications with one’s supervisor is related to better job performance ratings and overall organizational performance (Snyder and Morris, 1984; Kacmar, Witt, Zivnuska and Guly, 2003). Research also shows that lateral communication done between peers can influence important organizational outcomes such as turnover (Krackhardt and Porter, 1986).

External Communications

External communications deliver messages to individuals outside an organization. They may announce changes in staff, strategy, or earnings to shareholders; or they might be service announcements or ads for the general public, for example. The goal of an external communication is to create a specific message that the receiver will understand and/or share with others. Examples of external communications include the following:

Press Releases

Public relations professionals create external communications about a client’s product, services, or practices for specific receivers. These receivers, it is hoped, will share the message with others. In time, as the message is passed along, it should appear to be independent of the sender, creating the illusion of an independently generated consumer trend or public opinion.

The message of a public relations effort may be B2B (business to business), B2C (business to consumer), or media related. The message can take different forms. Press releases try to convey a newsworthy message, real or manufactured. It may be constructed like a news item, inviting editors or reporters to reprint the message, in part or as a whole, and with or without acknowledgment of the sender’s identity. Public relations campaigns create messages over time, through contests, special events, trade shows, and media interviews in addition to press releases.

Ads

Advertisements present external business messages to targeted receivers. Advertisers pay a fee to a television network, website, or magazine for an on-air, site, or publication ad. The fee is based on the perceived value of the audience who watches, reads, or frequents the space where the ad will appear.

In recent years, receivers (the audience) have begun to filter advertisers’ messages through technology such as ad blockers, the ability to fast-forward live or recorded TV through PVRs, paid subscriptions to Internet media, and so on. This trend grew as a result of the large amount of ads the average person sees each day and a growing level of consumer weariness of paid messaging. Advertisers, in turn, are trying to create alternative forms of advertising that receivers will not filter. For example, The advertorial is one example of an external communication that combines the look of an article with the focused message of an ad. Product placements in videos, movies, and games are other ways that advertisers strive to reach receivers with commercial messages.

Websites

A website may combine elements of public relations, advertising, and editorial content, reaching receivers on multiple levels and in multiple ways. Banner ads and blogs are just a few of the elements that allow a business to deliver a message to a receiver online. Online messages are often less formal and more approachable, particularly if intended for the general public. A message relayed in a daily blog post will reach a receiver differently than if it is delivered in an annual report, for example.

The popularity and power of blogs is growing. In fact, blogs have become so important to some companies as Coca-Cola, Kodak, and Marriott that they have created official positions within their organizations titled Chief Blogging Officer (Workforce Management, 2008). The real-time quality of web communications may appeal to receivers who filter out a traditional ad and public relations message because of its prefabricated quality.

Customer Communications

Customer communications can include letters, catalogues, direct mail, emails, text messages, and telemarketing messages. Some receivers automatically filter bulk messages like these; others will be receptive. The key to a successful external communication to customers is to convey a business message in a personally compelling way—dramatic news, a money-saving coupon, and so on. Customers will think What’s in it for me? when deciding how to respond to these messages, so clear benefits are essential.

Conclusion

Different communication channels are more or less effective at transmitting different kinds of information. Some types of communication range from high richness in information to medium and low richness. In addition, communications flow in different directions within organizations. A major internal communication channel is email, which is convenient but needs to be handled carefully. External communication channels include PR/press releases, ads, websites, and customer communications such as letters and catalogues.

Learning Highlights

- To communicate effectively, we need to align our body language, appearance, and tone with the words we are trying to convey.

- Different communication channels are more or less effective at transmitting different kinds of information. Some types of communication are information rich while others are medium rich.

- Communications flow in different directions within organizations.

- A major internal communication channel is email, which is convenient but needs to be handled carefully.

- External communication channels include PR/press releases, ads, websites, and customer communications such as letters and catalogues.

Check Your Understanding

References

Allen, D. G., and Griffeth, R. W. (1997). Vertical and lateral information processing: the effects of gender, employee classification level, and media richness on communication and work outcomes. Human Relations, (10), 1239.

Barry, B., and Fulmer, I. S. (2004). The Medium and the Message: The Adaptive Use of Communication Media in Dyadic Influence. The Academy of Management Review, (2). 272.

Daft, R. L., and Lenge, R. H. (1984). Information richness: A new approach to managerial behavior and organizational design. In B. Staw & L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (Vol. 6, pp. 191–233). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Ekman, P., Friesen, W. V., and Hager, J. C. The facial action coding system (FACS).

Fulk, J., and Boyd, B. (1991). Emerging theories of communication in organizations. Journal of Management, (2). 407.

Gifford, R., Ng, C. F., and Wilkinson, M. (1985). Nonverbal cues in the employment interview: Links between applicant qualities and interviewer judgments. Journal of Applied Psychology, 70(4), 729.

David K. Isom. (2005, October 19). Electronic discovery: New power, new risks. Web.

Kacmar, K. M., Witt, L., Zivnuska, S., and Gully, S. M. (2003). The interactive effect of leader-member exchange and communication frequency on performance ratings. Journal Of Applied Psychology, (4), 764.

Kiely, M. (1993). When “no” means “yes.” Marketing, (7), 9.

Krackhardt, D., and Porter, L. W. (1986). The snowball effect: turnover embedded in communication networks. Journal Of Applied Psychology, (1), 50.

Kruger, J., Epley, N., Parker, J., and Ng, Z. (2005). Egocentrism over E-Mail: can we communicate as well as we think?. Journal Of Personality And Social Psychology, (6), 925.

Lee, D., and Hatesohl, D. (n.d.) Listening: Our most used communication skill.

Lengel, R. H., and Daft, D. L. (1988). The selection of communication media as an executive skill. The Academy of Management Executive, 11, 225–232.

Luthans, F., and Larsen, J. K. (1986). How Managers Really Communicate. Human Relations, 39(2), 161.

Mehrabian, A. (1981). Silent messages. 2nd ed. Belmont. CA: Wadsworth.

Snyder, R. A., and Morris, J. H. (1984). Organizational Communication and Performance. Journal Of Applied Psychology, 69(3), 461-465.

Statistics Canada. (2010). Business and government use of information and communications technologies (Enterprises that use electronic mail).

Yates, J., & Orlikowski, W. J. (1992). Genres of Organizational Communication: A Structurational Approach to Studying Communication and Media. Academy Of Management Review, 17(2), 299-326. doi:10.5465/AMR.1992.4279545.

Chief blogging officer title catching on with corporations. (2008, May 1). Workforce Management News in Brief.

Attribution Statement (Channels)

This chapter is a remix containing content from a variety of sources published under a variety of open licenses, including the following:

Chapter Content

- Original content contributed by the Olds College OER Development Team, of Olds College to Professional Communications Open Curriculum under a CC-BY 4.0 license

- Content created by Anonymous for Communication Channels, in Management Principles, previously shared under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 license

- Content created by Anonymous for Different Types of Communication, in Management Principles, previously shared under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 license

Check Your Understandings

- Original assessment items contributed by the Olds College OER Development Team, of Olds College to Professional Communications Open Curriculum under a CC-BY 4.0 license

- Assessment items created by The Saylor Foundation for a Saylor.org course BUS210: Corporate Communication Quiz 11, previously shared under a CC BY 3.0 US license

- Assessment items created by The Saylor Foundation for a Saylor.org course BUS210: Corporate Communication Quiz 12, previously shared under a CC BY 3.0 US license

A medium for communication or the passage of information

(Channel) Relating to or in the form of words; spoken rather than written communication

(Channel using) Mark (letters, words, or other symbols) on a surface, typically paper, with a pen, pencil, or similar implement

(Channel) Not involving or using words or speech

The tone, pace, and volume of speech

Not existing or occurring at the same time

Verbal, non-verbal, and written communication channels are the three principal communication channels

Information that conveys more non-verbal information is considered the most rich, followed by verbal communications, then written communications, which are the least rich.

The professional maintenance of a favourable public image by a company, organization, or famous person