Introduction

2

Explaining the title ‘Demystifying academic English: Advanced Integrated Skills for Translingual Students of English’

When I was working on my doctoral dissertation in the early 2010s, I had many meetings and discussions with my advisor, Dr. Linda Valli. In one of those meetings, I was explaining to her why I was focusing on providing deep explanations of doing practitioner research as a dissertation and the words popped out of my mouth, “I want to demystify research.” That bit of conversation stuck in my memory, and as I look back on all the diverse teaching and research experiences I have had over the years, I realize that I have always endeavored to ‘demystify’, for my students, whatever it was that I was teaching: English, how to teach English, or how to do research on the teaching of English. Hence, the first part of the title: ‘Demystifying Academic English’. In the second part of the title, I use the term ‘translingual’ deliberately. Translingual speakers and writers of English have the ability to move across and beyond different languages and language varieties to achieve successful communication in both written and oral forms. Learners of academic English in U.S. community college academic English programs often demonstrate translingual competence, as they have already mastered at least one language (often referred to as their ‘home language’, ‘heritage language’, or ‘first language’) and are now acquiring the skills to use English appropriately in academic contexts. Oftentimes, academic English learners are bilingual or multilingual.

I have been writing (and presenting) extensively about translingualism in other places (e.g. Jain, 2020; Jain, 2019, Jain, 2018; Jain, 2014; Motha, Jain, & Tecle, 2012), but I provide a brief explanation here for my rationale for using the term ‘translingual students of English’ in the place of the more commonly-used ‘non-native English speakers/students’. While the label ‘non-native English speakers’ is still commonly used in many ELT settings in the U.S., the term tends to focus more on what’s not there (e.g. ‘does not speak English as a first language’) and carries an underlying negative connotation (e.g. ‘does not speak English fluently’ or ‘speaks English with an accent’[1]) and comes from a more monolingual (and, one could argue, a more deficit) orientation; The term ‘translingual’ stems from an additive orientation, on the other hand, by focusing on what is there, which is the ability to use codes across languages and language varieties appropriately and contextually to facilitate successful communication. In addition, the use of the term ‘non-native English speaker’ has also been occasionally tied to instances of racism and linguicism in many contexts around the world. Further, given that English is an international language spoken widely around the world with variations within and across national contexts both in terms of its long history and the current era of globalization, the terms ‘native’ and ‘non-native’ themselves continue to be deeply problematized by linguists and scholars for being an instance of an artificial dichotomy that fails to capture the far more complex and layered realities of today’s multilingual speakers.[2] From a social justice perspective, the term ‘translingual’ is thus more equitable than the terms ‘native’ and ‘non-native’.

Using this textbook

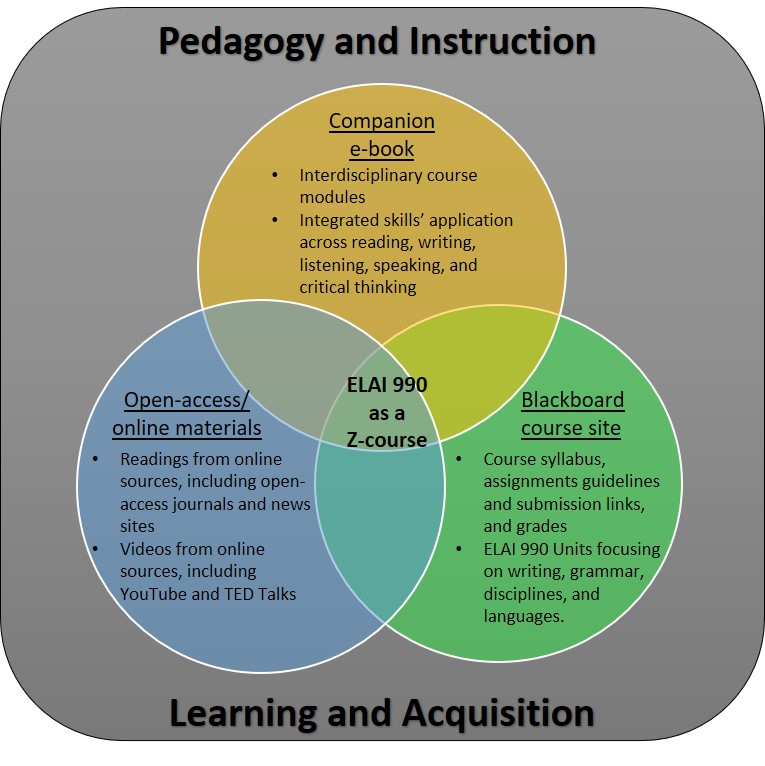

This companion ebook has been designed specially for my ELAI 990 z-course format, and is expected to work in conjunction with the course site and materials that are available publicly online. The need for this type of text emerged when I began to teach my courses in a z-format. I searched for textbooks that were part of Open Educational Resources (OERs), but even an extensive search failed to bring up a text that I could use as is in my integrated skills course. Thus, to bridge the gap that I identified in existing body of OERs, and to facilitate instruction in my courses, I have created this companion ebook. The framework below describes the z-format, and where this ebook fits in, in some more detail.

For colleagues interested in adapting this text to their own pedagogical contexts, I would encourage them to create their own frameworks that would work effectively in their specific classes. However, I share some details here that might be helpful in understanding how I use the companion ebook in my own specific ELAI 990 course.

I generally teach ELAI 990 over a span of 15 weeks in a regular semester (and in about six weeks in an intensive summer session). I distribute the modules across different semesters in an academic year using these two combinations: Module 1 + Module 2 + Module 3 + Module 4 in one semester and Module 1 + Module 5 + Module 6 + Module 7 in another semester. This ensures variability and gives me time to update modules as needed (for instance, by replacing an older reading with a more recent one, and then modify related assignments accordingly).

In terms of time distribution within each semester, Module 1 spans the first week and sets the foundation that the subsequent modules, spanning three weeks each, build upon. The first day of the semester is generally devoted to diagnostics and introductions (including a course overview). After the next module is completed, a week is dedicated to grammar and editing practice and a class test, and the same pattern is repeated after each of the remaining two modules. The last week of classes focuses on course review and preparation for the final examination, which takes place in the examination week. Here is a sample course schedule for a 15-week spring semester that explains this in more detail.

| Weeks | Module/Theme | Week’s focus | Day 1 (Tuesday) | Day 2 (Thursday) |

| 1 | Module 1: Globalization and Global Competence | Introductions | Course introductions and diagnostics | Introducing and exploring ‘global competence’ |

| 2 | Module 2: Global Englishes and Multilingual English Speakers | Analyzing sources of information | Analyzing videos | Analyzing the main reading |

| 3 | Essay Compositions: Processes and Products | From reading to writing; Understanding the process of composing essays | In-class essay draft – Listing and describing causes | |

| 4 | Presentations: Processes and Products | Understanding the process of creating group Power-Point presentations | Presentation 1: Group Power-Point – Listing and describing effects | |

| 5 | Module Review | Grammar and Editing Practice | Class Test 1 – Timed in-class essay | |

| 6 | Module 3: Globalization and Community Colleges | Analyzing sources of information | Analyzing videos | Analyzing the main reading |

| 7 | Essay Compositions: Processes and Products | From reading to writing; Understanding the process of composing essays | In-class essay draft – Listing and describing problems | |

| 8 | SPRING BREAK | |||

| 9 | Presentations: Processes and Products | Understanding the process of creating group poster presentations | Presentation 2: Group Poster – Listing and describing solutions | |

| 10 | Module Review | Grammar and Editing Practice | Class Test 2 – Timed in-class essay | |

| 11 | Module 4: Global Migration and Transnational Migrants | Analyzing sources of information | Analyzing videos | Analyzing the main reading |

| 12 | Essay Compositions: Processes and Products | From reading to writing; Understanding the process of composing essays | In-class essay draft – Taking a position and supporting it with convincing ideas | |

| 13 | Presentations: Processes and Products | Understanding the process of giving an individual presentation | Presentation 3: Individual Talk/Power-Point/Poster – Taking a position and supporting it with convincing ideas | |

| 14 | Module Review | Grammar and Editing Practice | Class Test 3 – Timed in-class essay | |

| 15 | Finals’ Review and Practice | Course Review and Practice | Course Review and Practice | |

| 16 | May 12 Final Exam 2:45pm to 4:45pm |

My Teaching Philosophy and My Pedagogical Approach

As part of my teaching philosophy, I believe that all students bring diverse knowledge, experiences, and skills to the classroom, and an effective teacher responds to this diversity by drawing upon it effectively in her pedagogy. As you read through the chapters in book, you will able to see how I endeavor to embed the pedagogy in students’ own lived experiences.

Just as I try to draw upon my students’ diverse backgrounds in crafting the curriculum for the course, I drew upon my own diverse professional and academic experiences in the making of this companion ebook. These span India and the U.S. and include: web-based content creation and print editorial experiences, such as creating textbooks in a multinational company in India and producing curricular materials as a teacher and teacher educator in the U.S.; experiences learning academic languages (Hindi, English, and Sanskrit) as school subjects and learning a foreign language (German) as an adult in college settings; and being a language teacher in India and the U.S., and a language teacher educator and researcher in the U.S. (I even drew upon the basic HTML /website designing lessons I had taken in Delhi back in the late 90s and more recent amateur photography skills to make tiny tweaks in the text in this book and to design the cover.)

I employ critical pragmatism (Pennycook, 1997) and critical pragmatic EAP (Harwood and Hadley, 2004) in teaching academic English courses, in terms of “looking beyond language simply as structure and representation in favour of a view of language as always engaged in the construction of how we understand the world” (Pennycook, 1997, p. 258). One challenge, among many, in approaching EAP from this perspective is how to translate this approach into meaningful and effective pedagogy — one that prepares students to cross borders from EAP to credit-based college coursework successfully, while also building their critical thinking skills and agency as learners. I endeavor to ‘demystify’ (Harwood and Hadley, 2004) academic English tasks and related processes by connecting abstract concepts with concrete everyday lived experiences that students can relate to easily and thus make the cognitive leap of comprehending the much more abstract academic concepts that they also need to master. Additionally, creating a curriculum around the concept of global competence helps move learning in the direction of the “pluralisation of knowledge” in terms of enabling students to “become aware of alternative ways of envisioning the world” (Pennycook, 1997, p. 264).[3]

- The idea that some people speak English 'with an accent' is fallacious, as anyone who speaks any language has an accent. The idea of English being 'accentless' is thus linguistically misleading. Everyone speaks with an accent, but certain accents are 'marked' as different and therefore often devalued as well. ↵

- This discussion lends itself well to critical thinking tasks, as explored in Module 2. ↵

- I also use an approach that I can 'translingually responsive pedagogy', as I discuss in a presentation I gave as part of the 2018 Scholarship in Excellence of Teaching at my institution, Montgomery College. For those interested in exploring other resources that also take a translingual approach to teaching academic English, Purdue University's Online Writing Lab's Translingual Writing resource for teachers and tutors is an excellent place to start. ↵