17

CLASSICAL ESSAY STRUCTURE

The following videos provide an explanation of the classical model of structuring a persuasive argument. You can access the slides alone, without narration, here.

Licensing & AttributionsCC licensed content, Shared previouslyComposition II. Authored by: Alexis McMillan-Clifton. Provided by: Tacoma Community College. Located at: http://www.tacomacc.edu. Project: Kaleidoscope Open Course Initiative. License: CC BY: Attribution102 S11 Classical I. Authored by: Alexis McMillan-Clifton. Located at: https://youtu.be/kraJ2Juub5U. License: CC BY: Attribution102 S11 Classical II. Authored by: Alexis McMillan-Clifton. Located at: https://youtu.be/3m_EP-BPsBs. License: CC BY: Attribution

Watch this video online: https://youtu.be/kraJ2Juub5U Watch this video online: https://youtu.be/3m_EP-BPsBs

DISCUSSION: ARGUMENT/COUNTERARGUMENT

This will be a small group discussion—you’ll only see posts from a smaller group of people.

Previously you did some great work identifying your target audience for your research project. The whole fun of writing a persuasive paper is to pick an audience who disagrees with you, or at least is undecided about the matter. Then you use charm, wit, and raw intelligence to prove that they’re absolutely silly for thinking what they do, and that they better come over to your side or else the world will end.

In being persuasive and winning the fight, it helps a lot to remember that your target audience has reasons for their position on the issue. Those reasons may not be GOOD ones, of course, but they have some motivation for thinking or feeling the way they do. (I still don’t like eating at Jack in the Box because a friend of mine had a really bad experience there years ago, in another state. Not a very rational reason, I admit, but it does shape my behavior when it comes to fast food.)

In order to be truly persuasive, you have to understand what people’s motivations are, and acknowledge those in your essay. If you don’t, then readers will think one of two things: 1) you don’t know what the other side thinks, and are therefore ignorant, or 2) you know what they think, but you just don’t have any good response for it and are avoiding it.

I’d like you to visit POWA’s “Anticipating Opposition” article and read the content there. Then, return to this discussion and build your own pro/con chart, using your thesis as the “proposition.” It’ll be easier to create a list, rather than a chart, given our constraints in the discussion forum platform.

Then look at one or two of your “con” statements in more detail. How will you acknowledge these arguments in your own essay, and what will you say to your reader to counter them? For instance, if I were trying to talk myself into eating at Jack in the Box again, I’d acknowledge that finding a bug in your food is yes, a traumatic event. But it was an isolated incident, and in no way reflects the standards of the chain overall. I’d go into food safety data and possibly relate the health scores of the local franchises recently. Maybe I’d even embark on a smear campaign and talk about similar events that have occurred at other fast food chains, to show it’s not particular to one brand.

Your post should be at least 150-200 words. It doesn’t have to be grammatically perfect, but should use standard English (no text-speak, please) and normal capitalization rules.

You will also need to return to this Discussion to reply to at least one of your group members’ posts. Content could include, but is not limited to, any of the following: Suggest further elements that could be added either to the Pro or Con side of their chart. Indicate what it would take for you to be convinced, if you were on the con side of the argument.

Responses are weighed as heavily as your initial posting, and should be roughly as long (150-200 words). Responses should indicate you’ve read your classmate’s post carefully. Include specific details from the post you’re responding to in your reply.

|

Licensing & Attributions CC licensed content, Shared previously Composition II. Authored by: Alexis McMillan-Clifton. Provided by: Tacoma Community College. Located at: http://www.tacomacc.edu. Project: Kaleidoscope Open Course Initiative. License: CC BY: Attribution |

WRITING FOR SUCCESS: OUTLINING

|

LEARNING OBJECTIVES |

|

By the end of this section, you will be able to: Identify the steps in constructing an outline. Construct a topic outline and a sentence outline. |

Your prewriting activities and readings have helped you gather information for your assignment. The more you sort through the pieces of information you found, the more you will begin to see the connections between them. Patterns and gaps may begin to stand out. But only when you start to organize your ideas will you be able to translate your raw insights into a form that will communicate meaning to your audience.

|

Tip |

|

Longer papers require more reading and planning than shorter papers do. Most writers discover that the more they know about a topic, the more they can write about it with intelligence and interest. |

Organizing Ideas

When you write, you need to organize your ideas in an order that makes sense. The writing you complete in all your courses exposes how analytically and critically your mind works. In some courses, the only direct contact you may have with your instructor is through the assignments you write for the course. You can make a good impression by spending time ordering your ideas.

Order refers to your choice of what to present first, second, third, and so on in your writing. The order you pick closely relates to your purpose for writing that particular assignment. For example, when telling a story, it may be important to first describe the background for the action. Or you may need to first describe a 3-D movie projector or a television studio to help readers visualize the setting and scene. You may want to group your support effectively to convince readers that your point of view on an issue is well reasoned and worthy of belief.

In longer pieces of writing, you may organize different parts in different ways so that your purpose stands out clearly and all parts of the paper work together to consistently develop your main point.

Methods of Organizing Writing

The three common methods of organizing writing are chronological order, spatial order, and order of importance. You will learn more about these in Chapter 8 “Writing Essays: From Start to Finish”; however, you need to keep these methods of organization in mind as you plan how to arrange the information you have gathered in an outline. An outline is a written plan that serves as a skeleton for the paragraphs you write. Later, when you draft paragraphs in the next stage of the writing process, you will add support to create “flesh” and “muscle” for your assignment.

When you write, your goal is not only to complete an assignment but also to write for a specific purpose—perhaps to inform, to explain, to persuade, or for a combination of these purposes. Your purpose for writing should always be in the back of your mind, because it will help you decide which pieces of information belong together and how you will order them. In other words, choose the order that will most effectively fit your purpose and support your main point.

Table 7.1 “Order versus Purpose” shows the connection between order and purpose. Table 7.1 Order versus Purpose

|

Order |

Purpose |

|

Chronological Order |

To explain the history of an event or a topic |

|

To tell a story or relate an experience |

|

|

To explain how to do or make something |

|

|

To explain the steps in a process |

|

|

Spatial Order |

To help readers visualize something as you want them to see it |

|

To create a main impression using the senses (sight, touch, taste, smell, and sound) |

|

|

Order of Importance |

To persuade or convince |

|

To rank items by their importance, benefit, or significance |

|

Writing a Thesis Statement

One legitimate question readers always ask about a piece of writing is “What is the big idea?” (You may even ask this question when you are the reader, critically reading an assignment or another document.) Every nonfiction writing task—from the short essay to the ten-page term paper to the lengthy senior thesis—needs a big idea, or a controlling idea, as the spine for the work. The controlling idea is the main idea that you want to present and develop.

|

Tip |

|

For a longer piece of writing, the main idea should be broader than the main idea for a shorter piece of writing. Be sure to frame a main idea that is appropriate for the length of the assignment. Ask yourself, “How many pages will it take for me to explain and explore this main idea in detail?” Be reasonable with your estimate. Then expand or trim it to fit the required length. |

The big idea, or controlling idea, you want to present in an essay is expressed in a thesis statement. A thesis statement is often one sentence long, and it states your point of view. The thesis statement is not the topic of the piece of writing but rather what you have to say about that topic and what is important to tell readers.

Table 7.2 “Topics and Thesis Statements” compares topics and thesis statements. Table 7.2 Topics and Thesis Statements

|

Topic |

Thesis Statement |

|

Music piracy |

The recording industry fears that so-called music piracy will diminish profits and destroy markets, but it cannot be more wrong. |

|

The number of consumer choices available in media gear |

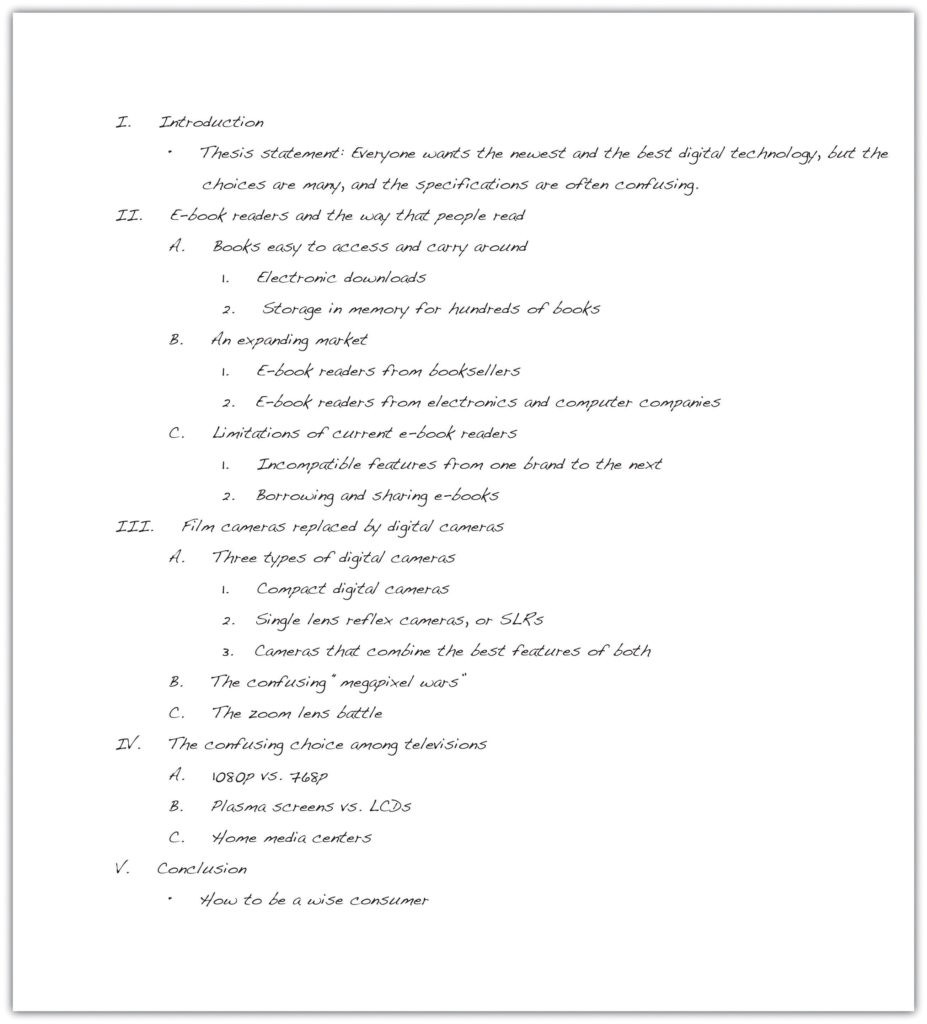

Everyone wants the newest and the best digital technology, but the choices are extensive, and the specifications are often confusing. |

|

E-books and online newspapers increasing their share of the market |

E-books and online newspapers will bring an end to print media as we know it. |

|

Online education and the new media |

Someday, students and teachers will send avatars to their online classrooms. |

The first thesis statement you write will be a preliminary thesis statement, or a working thesis statement. You will need it when you begin to outline your assignment as a way to organize it. As you continue to develop the arrangement, you can limit your working thesis statement if it is too broad or expand it if it proves too narrow for what you want to say.

|

Tip |

|

You will make several attempts before you devise a working thesis statement that you think is effective. Each draft of the thesis statement will bring you closer to the wording that expresses your meaning exactly. |

Writing an Outline

For an essay question on a test or a brief oral presentation in class, all you may need to prepare is a short, informal outline in which you jot down key ideas in the order you will present them. This kind of outline reminds you to stay focused in a stressful situation and to include all the good ideas that help you explain or prove your point.

For a longer assignment, like an essay or a research paper, many college instructors require students to submit a formal outline before writing a major paper as a way to be sure you are on the right track and are working in an organized manner. A formal outline is a detailed guide that shows how all your supporting ideas relate to each other. It helps you distinguish between ideas that are of equal importance and ones that are of lesser importance. You build your paper based on the framework created by the outline.

|

Tip |

|

Instructors may also require you to submit an outline with your final draft to check the direction of the assignment and the logic of your final draft. If you are required to submit an outline with the final draft of a paper, remember to revise the outline to reflect any changes you made while writing the paper. |

- Place your introduction and thesis statement at the beginning, under roman numeral I.

- Use roman numerals (II, III, IV, V, etc.) to identify main points that develop the thesis statement.

- Use capital letters (A, B, C, D, etc.) to divide your main points into parts.

- Use arabic numerals (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, etc.) if you need to subdivide any As, Bs, or Cs into smaller parts.

- End with the final roman numeral expressing your idea for your conclusion.

Here is what the skeleton of a traditional formal outline looks like. The indention helps clarify how the ideas are related.

- IntroductionThesis statement

- Main point 1 → becomes the topic sentence of body paragraph 1

- Supporting detail → becomes a support sentence of body paragraph 1

- Subpoint

- Subpoint

- Supporting detail

- Subpoint

- Subpoint

- Supporting detail

- Subpoint

- Subpoint

- Main point 2 → becomes the topic sentence of body paragraph 2

- Supporting detail

- Supporting detail

- Supporting detail

- Main point 3 → becomes the topic sentence of body paragraph 3

- Supporting detail

- Supporting detail

- Supporting detail

- Conclusion

|

Tip |

|

In an outline, any supporting detail can be developed with subpoints. For simplicity, the model shows them only under the first main point. |

|

Formal outlines are often quite rigid in their organization. As many instructors will specify, you cannot subdivide one point if it is only one part. For example, for every roman numeral I, there must be a For every A, there must be a B. For every arabic numeral 1, there must be a 2. See for yourself on the sample outlines that follow. |

Constructing Topic Outlines

A topic outline is the same as a sentence outline except you use words or phrases instead of complete sentences. Words and phrases keep the outline short and easier to comprehend. All the headings, however, must

be written in parallel structure. (For more information on parallel structure, see “Refining Your Writing: How Do I Improve My Writing Technique?”.)

Here is the topic outline that Mariah constructed for the essay she is developing. Her purpose is to inform, and her audience is a general audience of her fellow college students. Notice how Mariah begins with her thesis statement. She then arranges her main points and supporting details in outline form using short phrases in parallel grammatical structure.

Checklist

Writing an Effective Topic Outline

This checklist can help you write an effective topic outline for your assignment. It will also help you discover where you may need to do additional reading or prewriting.

- Do I have a controlling idea that guides the development of the entire piece of writing?

- Do I have three or more main points that I want to make in this piece of writing? Does each main point connect to my controlling idea?

- Is my outline in the best order—chronological order, spatial order, or order of importance—for me to present my main points? Will this order help me get my main point across?

- Do I have supporting details that will help me inform, explain, or prove my main points?

- Do I need to add more support? If so, where?

- Do I need to make any adjustments in my working thesis statement before I consider it the final version?

Writing at Work

Word processing programs generally have an automatic numbering feature that can be used to prepare outlines. This feature automatically sets indents and lets you use the tab key to arrange information just as you would in an outline. Although in business this style might be acceptable, in college your instructor might have different requirements. Teach yourself how to customize the levels of outline numbering in your word-processing program to fit your instructor’s preferences.

Constructing Sentence Outlines

A sentence outline is the same as a topic outline except you use complete sentences instead of words or phrases. Complete sentences create clarity and can advance you one step closer to a draft in the writing process.

Here is the sentence outline that Mariah constructed for the essay she is developing.

II.t:-6oo,f reader$ are Chan§”:} the ‘–‘o/ ;>eo,Ple read.

4.t:-6ool: readers ,,.,4., ¢oo,(:s easy to access and to car,y.

1.Boo/:s can be d=,/oaded elec(ron,‘aclly.

:,, ]>,w:c..s can stor« l1undr«ds cl’ ¢oo,(:s :n M«Mo,y .

,.Boo/:sellers sell th,.:r own e-6oo.f readers.

:,. t:leetron,’cs and COM,P«cer c.OM,Pa,,eS also sell e-6oo.f readers .

1.thtt dev‘ ,c eS are o,..;ned 6y d:/’lerent ¢rands and “‘o/ netbeCOA1,Pat:6le.

:,,hw,Pr0jra”1S have been made to .r.t t/1« ot/1.tr W<1/ 4mer:cans read’

6y ,>orroN;n:J 6oo/:s ./’r°”‘ l:6rar:es.

II I .l>j,’tal Ca”1era.5 l1aYe almo.5t totally re,Placed ,r,1,,., ccvnera.5.

,l.the .r.rst “”tior cho:ce :s the ty,Pe cl’ d j‘, t al camera.

I.Co ,;ct dj,’tal cameras are l,’Jht 6ut have f”ewer =:J”,P;><el.5.

3-Sc,,.,,. caA1eras c.OM6.‘ne the best /’eatureS ol’ coM,Pacts and S Ll{‘s.

- Choo.5:n:J the CaA1era ty,Pe ;nv’ofv’eS the conl’u.5:n:J• “‘e:f”<,P;><el ,..;ar.5.··

- th,, ZOOA1 lenS 6attl,. also det,.,-,.,;,,.,,s the caA1era yott w,’II 6,,y.

Iv.,loth:n:J ;.5 Mor<, c onl’u.5:n:J to,,,.. than c.hoo.5:n:J “””on:’/ telev.’s;on.5,

d.Zn the ,-,-so/ut:on wars, Nhat are the bene.r.ts o/’ •O•Of’ and 7-t,,’ijf’?

B.Z.,, th,, sc.reen-.s:ze ,..;ars, ,..,/,at do ,Pla.5Ma .sc.reenS and Lc:J> screen$ o/’/’er?

C,l>c,,..5 “””‘Y hOA1d really ne«d a med:a c.,,,t,.,.?

|

Tip |

|

The information compiled under each roman numeral will become a paragraph in your final paper. In the previous example, the outline follows the standard five-paragraph essay arrangement, but longer essays will require more paragraphs and thus more roman numerals. If you think that a paragraph might become too long or stringy, add an additional paragraph to your outline, renumbering the main points appropriately. |

PowerPoint presentations, used both in schools and in the workplace, are organized in a way very similar to formal outlines. PowerPoint presentations often contain information in the form of talking points that the presenter develops with more details and examples than are contained on the PowerPoint slide.

|

Key Takeaways |

|

Writers must put their ideas in order so the assignment makes sense. The most common orders are chronological order, spatial order, and order of importance. After gathering and evaluating the information you found for your essay, the next step is to write a working, or preliminary, thesis statement. The working thesis statement expresses the main idea that you want to develop in the entire piece of writing. It can be modified as you continue the writing process. Effective writers prepare a formal outline to organize their main ideas and supporting details in the order they will be presented. A topic outline uses words and phrases to express the ideas. A sentence outline uses complete sentences to express the ideas. The writer’s thesis statement begins the outline, and the outline ends with suggestions for the concluding paragraph. |

|

Using the topic you selected in “Apply Prewriting Models,” develop a working thesis statement that states your controlling idea for the piece of writing you are doing. On a sheet of paper, write your working thesis statement.

Using the working thesis statement you wrote in #1 and the reading you did in “Apply Prewriting Models,” construct a topic outline for your essay. Be sure to observe correct outline form, including correct indentions and the use of Roman and arabic numerals and capital letters. Please share with a classmate and compare your outline. Point out areas of interest from their outline and what you would like to learn more about.

Expand the topic outline you prepared #2 to make it a sentence outline. In this outline, be sure to include multiple supporting points for your main topic even if your topic outline does not contain them. Be sure to observe correct outline form, including correct indentions and the use of Roman and arabic numerals and capital letters. |

|

Licensing & Attributions CC licensed content, Shared previously Successful Writing. Authored by: Anonymous. Provided by: Anonymous. Located at: http://2012books.lardbucket.org/books/english-for-business-success/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike |

INTRODUCTIONS

WHAT THIS HANDOUT IS ABOUT

This handout will explain the functions of introductions, offer strategies for writing effective ones, help you check your drafted introductions, and provide you with examples of introductions to be avoided.

THE ROLE OF INTRODUCTIONS

Introductions and conclusions can be the most difficult parts of papers to write. Usually when you sit down to respond to an assignment, you have at least some sense of what you want to say in the body of your paper. You might have chosen a few examples you want to use or have an idea that will help you answer the main question of your assignment: these sections, therefore, are not as hard to write. But these middle parts of the paper can’t just come out of thin air; they need to be introduced and concluded in a way that makes sense to your reader.

Your introduction and conclusion act as bridges that transport your readers from their own lives into the “place” of your analysis. If your readers pick up your paper about education in the autobiography of Frederick Douglass, for example, they need a transition to help them leave behind the world of Chapel Hill, television, e-mail, and the The Daily Tar Heel and to help them temporarily enter the world of nineteenth-century American slavery. By providing an introduction that helps your readers make a transition between their own world and the issues you will be writing about, you give your readers the tools they need to get into your topic and care about what you are saying. Similarly, once you’ve hooked your reader with the introduction and offered evidence to prove your thesis, your conclusion can provide a bridge to help your readers make the transition back to their daily lives. (See our handout on conclusions.)

WHY BOTHER WRITING A GOOD INTRODUCTION?

You never get a second chance to make a first impression. The opening paragraph of your paper will provide your readers with their initial impressions of your argument, your writing style, and the overall quality of your work. A vague, disorganized, error-filled, off-the-wall, or boring introduction will probably create a negative impression. On the other hand, a concise, engaging, and well-written introduction will start your readers off thinking highly of you, your analytical skills, your writing, and your paper. This impression is especially important when the audience you are trying to reach (your instructor) will be grading your work.

Your introduction is an important road map for the rest of your paper. Your introduction conveys a lot of information to your readers. You can let them know what your topic is, why it is important, and how you plan to proceed with your discussion. In most academic disciplines, your introduction should contain a thesis that will assert your main argument. It should also, ideally, give the reader a sense of the kinds of information you will use to make that argument and the general organization of the paragraphs and pages that will follow. After reading your introduction, your readers should not have any major surprises in store when they read the main body of your paper.

Ideally, your introduction will make your readers want to read your paper. The introduction should capture your readers’ interest, making them want to read the rest of your paper. Opening with a compelling story, a fascinating quotation, an interesting question, or a stirring example can get your readers to see why this topic matters and serve as an invitation for them to join you for an interesting intellectual conversation.

STRATEGIES FOR WRITING AN EFFECTIVE INTRODUCTION

Start by thinking about the question (or questions) you are trying to answer. Your entire essay will be a response to this question, and your introduction is the first step toward that end. Your direct answer to the assigned question will be your thesis, and your thesis will be included in your introduction, so it is a good idea to use the question as a jumping off point. Imagine that you are assigned the following question:

Education has long been considered a major force for American social change, righting the wrongs of our society. Drawing on theNarrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, discuss the relationship between education and slavery in 19th-century America. Consider the following: How did white control of education reinforce slavery?

How did Douglass and other enslaved African Americans view education while they endured slavery? And what role did education play in the acquisition of freedom? Most importantly, consider the degree to which education was or was not a major force for social change with regard to slavery.

You will probably refer back to your assignment extensively as you prepare your complete essay, and the prompt itself can also give you some clues about how to approach the introduction. Notice that it starts with a broad statement, that education has been considered a major force for social change, and then narrows to focus on specific questions from the book. One strategy might be to use a similar model in your own introduction —start off with a big picture sentence or two about the power of education as a force for change as a way of getting your reader interested and then focus in on the details of your argument about Douglass. Of course, a different approach could also be very successful, but looking at the way the professor set up the question can sometimes give you some ideas for how you might answer it.

Decide how general or broad your opening should be. Keep in mind that even a “big picture” opening needs to be clearly related to your topic; an opening sentence that said “Human beings, more than any other creatures on earth, are capable of learning” would be too broad for our sample assignment about slavery and education. If you have ever used Google Maps or similar programs, that experience can provide a helpful way of thinking about how broad your opening should be. Imagine that you’re researching Chapel Hill. If what you want to find out is whether Chapel Hill is at roughly the same latitude as Rome, it might make sense to hit that little “minus” sign on the online map until it has zoomed all the way out and you can see the whole globe. If you’re trying to figure out how to get from Chapel Hill to Wrightsville Beach, it might make more sense to zoom in to the level where you can see most of North Carolina (but not the rest of the world, or even the rest of the United States). And if you are looking for the intersection of Ridge Road and Manning Drive so that you can find the Writing Center’s main office, you may need to zoom all the way in. The question you are asking determines how “broad” your view should be. In the sample assignment above, the questions are probably at the “state” or “city” level of generality. But the introductory sentence about human beings is mismatched—it’s definitely at the “global” level. When writing, you need to place your ideas in context—but that context doesn’t generally have to be as big as the whole galaxy! (See our handout on understanding assignments for additional information on the hidden clues in assignments.)

Try writing your introduction last. You may think that you have to write your introduction first, but that isn’t necessarily true, and it isn’t always the most effective way to craft a good introduction. You may find that you don’t know what you are going to argue at the beginning of the writing process, and only through the experience of writing your paper do you discover your main argument. It is perfectly fine to start out thinking that you want to argue a particular point, but wind up arguing something slightly or even dramatically different by the time you’ve written most of the paper. The writing process can be an important way to organize your ideas, think through complicated issues, refine your thoughts, and develop a sophisticated argument. However, an introduction written at the beginning of that discovery process will not necessarily reflect what you wind up with at the end. You will need to revise your paper to make sure that the introduction, all of the evidence, and the conclusion reflect the argument you intend. Sometimes it’s easiest to just write up all of your evidence first and then write the introduction last—that way you can be sure that the introduction will match the body of the paper.

Don’t be afraid to write a tentative introduction first and then change it later. Some people find that they need to write some kind of introduction in order to get the writing process started. That’s fine, but if you are one of those people, be sure to return to your initial introduction later and rewrite if necessary.

Open with an attention grabber. Sometimes, especially if the topic of your paper is somewhat dry or technical, opening with something catchy can help. Consider these options:

- an intriguing example (for example, the mistress who initially teaches Douglass but then ceases her instruction as she learns more about slavery)

- a provocative quotation (Douglass writes that “education and slavery were incompatible with each other”)

- a puzzling scenario (Frederick Douglass says of slaves that “[N]othing has been left undone to cripple their intellects, darken their minds, debase their moral nature, obliterate all traces of their relationship to mankind; and yet how wonderfully they have sustained the mighty load of a most frightful bondage, under which they have been groaning for centuries!” Douglass clearly asserts that slave owners went to great lengths to destroy the mental capacities of slaves, yet his own life story proves that these efforts could be unsuccessful.)

- a vivid and perhaps unexpected anecdote (for example, “Learning about slavery in the American history course at Frederick Douglass High School, students studied the work slaves did, the impact of slavery on their families, and the rules that governed their lives. We didn’t discuss education, however, until one student, Mary, raised her hand and asked, ‘But when did they go to school?’ That modern high school students could not conceive of an American childhood devoid of formal education speaks volumes about the centrality of education to American youth today and also suggests the significance of the deprivation of education in past generations.”)

- a thought-provoking question (given all of the freedoms that were denied enslaved individuals in the American South, why does Frederick Douglass focus his attentions so squarely on education and literacy?)

Pay special attention to your first sentence. Start off on the right foot with your readers by making sure that the first sentence actually says something useful and that it does so in an interesting and error-free way.

Be straightforward and confident. Avoid statements like “In this paper, I will argue that Frederick Douglass valued education.” While this sentence points toward your main argument, it isn’t especially interesting. It might be more effective to say what you mean in a declarative sentence. It is much more convincing to tell us that “Frederick Douglass valued education” than to tell us that you are going to say that he did. Assert your main argument confidently. After all, you can’t expect your reader to believe it if it doesn’t sound like you believe it!

HOW TO EVALUATE YOUR INTRODUCTION DRAFT

Ask a friend to read it and then tell you what he or she expects the paper will discuss, what kinds of evidence the paper will use, and what the tone of the paper will be. If your friend is able to predict the rest of your paper accurately, you probably have a good introduction.

FIVE KINDS OF LESS EFFECTIVE INTRODUCTIONS

- The place holder introduction. When you don’t have much to say on a given topic, it is easy to create this kind of introduction. Essentially, this kind of weaker introduction contains several sentences that are vague and don’t really say much. They exist just to take up the “introduction space” in your paper. If you had something more effective to say, you would probably say it, but in the meantime this paragraph is just a place holder.

Example: Slavery was one of the greatest tragedies in American history. There were many different aspects of slavery. Each created different kinds of problems for enslaved people.

- The restated question introduction. Restating the question can sometimes be an effective strategy, but it can be easy to stop at JUST restating the question instead of offering a more specific, interesting introduction to your paper. The professor or teaching assistant wrote your questions and will be reading ten to seventy essays in response to them—he or she does not need to read a whole paragraph that simply restates the question. Try to do something more interesting.

Example: Indeed, education has long been considered a major force for American social change, righting the wrongs of our society. The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass discusses the relationship between education and slavery in 19th century America, showing how white control of education reinforced slavery and how Douglass and other enslaved African Americans viewed education while they endured. Moreover, the book discusses the role that education played in the acquisition of freedom. Education was a major force for social change with regard to slavery.

- The Webster’s Dictionary introduction. This introduction begins by giving the dictionary definition of one or more of the words in the assigned question. This introduction strategy is on the right track—if you write one of these, you may be trying to establish the important terms of the discussion, and this move builds a bridge to the reader by offering a common, agreed-upon definition for a key idea. You may also be looking for an authority that will lend credibility to your paper. However, anyone can look a word up in the dictionary and copy down what Webster says—it may be far more interesting for you (and your reader) if you develop your own definition of the term in the specific context of your class and assignment, or if you use a defintion from one of the sources you’ve been reading for class. Also recognize that the dictionary is also not a particularly authoritative work—it doesn’t take into account the context of your course and doesn’t offer particularly detailed information. If you feel that you must seek out an authority, try to find one that is very relevant and specific. Perhaps a quotation from a source reading might prove better? Dictionary introductions are also ineffective simply because they are so overused. Many graders will see twenty or more papers that begin in this way, greatly decreasing the dramatic impact that any one of those papers will have.

Example: Webster’s dictionary defines slavery as “the state of being a slave,” as “the practice of owning slaves,” and as “a condition of hard work and subjection.”

- The “dawn of man” introduction. This kind of introduction generally makes broad, sweeping statements about the relevance of this topic since the beginning of time. It is usually very general (similar to the place holder introduction) and fails to connect to the thesis. You may write this kind of introduction when you don’t have much to say—which is precisely why it is ineffective.

Example: Since the dawn of man, slavery has been a problem in human history.

- The book report introduction. This introduction is what you had to do for your elementary school book reports. It gives the name and author of the book you are writing about, tells what the book is about, and offers other basic facts about the book. You might resort to this sort of introduction when you are trying to fill space because it’s a familiar, comfortable format. It is ineffective because it offers details that your reader already knows and that are irrelevant to the thesis.

Example: Frederick Douglass wrote his autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, in the 1840s. It was published in 1986 by Penguin Books. In it, he tells the story of his life.

WORKS CONSULTED

We consulted these works while writing the original version of this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find the latest publications on this topic. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial.

All quotations are from Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, edited and with introduction by Houston A. Baker, Jr., New York: Penguin Books, 1986.

|

Licensing & Attributions CC licensed content, Shared previously Introductions. Provided by: UNC Writing Center. Located at: http://writingcenter.unc.edu/handouts/introductions/. License: CC BY-NC-ND: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives |

CONCLUSIONS

WHAT THIS HANDOUT IS ABOUT

This handout will explain the functions of conclusions, offer strategies for writing effective ones, help you evaluate your drafted conclusions, and suggest conclusion strategies to avoid.

ABOUT CONCLUSIONS

Introductions and conclusions can be the most difficult parts of papers to write. While the body is often easier to write, it needs a frame around it. An introduction and conclusion frame your thoughts and bridge your ideas for the reader.

Just as your introduction acts as a bridge that transports your readers from their own lives into the “place” of your analysis, your conclusion can provide a bridge to help your readers make the transition back to their daily lives. Such a conclusion will help them see why all your analysis and information should matter to them after they put the paper down.

Your conclusion is your chance to have the last word on the subject. The conclusion allows you to have the final say on the issues you have raised in your paper, to synthesize your thoughts, to demonstrate the importance of your ideas, and to propel your reader to a new view of the subject. It is also your opportunity to make a good final impression and to end on a positive note.

Your conclusion can go beyond the confines of the assignment. The conclusion pushes beyond the boundaries of the prompt and allows you to consider broader issues, make new connections, and elaborate on the significance of your findings.

Your conclusion should make your readers glad they read your paper. Your conclusion gives your reader something to take away that will help them see things differently or appreciate your topic in personally relevant ways. It can suggest broader implications that will not only interest your reader, but also enrich your reader’s life in some way. It is your gift to the reader.

STRATEGIES FOR WRITING AN EFFECTIVE CONCLUSION

One or more of the following strategies may help you write an effective conclusion.

- Play the “So What” Game. If you’re stuck and feel like your conclusion isn’t saying anything new or interesting, ask a friend to read it with you. Whenever you make a statement from your conclusion, ask the friend to say, “So what?” or “Why should anybody care?” Then ponder that question and answer it. Here’s how it might go:

You: Basically, I’m just saying that education was important to Douglass.

Friend: So what?

You: Well, it was important because it was a key to him feeling like a free and equal citizen.

Friend: Why should anybody care?

You: That’s important because plantation owners tried to keep slaves from being educated so that they could maintain control. When Douglass obtained an education, he undermined that control personally.

You can also use this strategy on your own, asking yourself “So What?” as you develop your ideas or your draft.

- Return to the theme or themes in the introduction. This strategy brings the reader full circle. For example, if you begin by describing a scenario, you can end with the same scenario as proof that your essay is helpful in creating a new understanding. You may also refer to the introductory paragraph by using key words or parallel concepts and images that you also used in the introduction.

- Synthesize, don’t summarize: Include a brief summary of the paper’s main points, but don’t simply repeat things that were in your paper. Instead, show your reader how the points you made and the support and examples you used fit together. Pull it all together.

- Include a provocative insight or quotation from the research or reading you did for your paper.

- Propose a course of action, a solution to an issue, or questions for further study. This can redirect your reader’s thought process and help her to apply your info and ideas to her own life or to see the broader implications.

- Point to broader implications. For example, if your paper examines the Greensboro sit-ins or another event in the Civil Rights Movement, you could point out its impact on the Civil Rights Movement as a

whole. A paper about the style of writer Virginia Woolf could point to her influence on other writers or on later feminists.

STRATEGIES TO AVOID

- Beginning with an unnecessary, overused phrase such as “in conclusion,” “in summary,” or “in closing.” Although these phrases can work in speeches, they come across as wooden and trite in writing.

- Stating the thesis for the very first time in the conclusion.

- Introducing a new idea or subtopic in your conclusion.

- Ending with a rephrased thesis statement without any substantive changes.

- Making sentimental, emotional appeals that are out of character with the rest of an analytical paper.

- Including evidence (quotations, statistics, etc.) that should be in the body of the paper.

FOUR KINDS OF INEFFECTIVE CONCLUSIONS

- The “That’s My Story and I’m Sticking to It” Conclusion. This conclusion just restates the thesis and is usually painfully short. It does not push the ideas forward. People write this kind of conclusion when they can’t think of anything else to say. Example: In conclusion, Frederick Douglass was, as we have seen, a pioneer in American education, proving that education was a major force for social change with regard to slavery.

- The “Sherlock Holmes” Conclusion. Sometimes writers will state the thesis for the very first time in the conclusion. You might be tempted to use this strategy if you don’t want to give everything away too early in your paper. You may think it would be more dramatic to keep the reader in the dark until the end and then “wow” him with your main idea, as in a Sherlock Holmes mystery. The reader, however, does not expect a mystery, but an analytical discussion of your topic in an academic style, with the main argument (thesis) stated up front. Example: (After a paper that lists numerous incidents from the book but never says what these incidents reveal about Douglass and his views on education): So, as the evidence above demonstrates, Douglass saw education as a way to undermine the slaveholders’ power and also an important step toward freedom.

- The “America the Beautiful”/”I Am Woman”/”We Shall Overcome” Conclusion. This kind of conclusion usually draws on emotion to make its appeal, but while this emotion and even sentimentality may be very heartfelt, it is usually out of character with the rest of an analytical paper. A more sophisticated commentary, rather than emotional praise, would be a more fitting tribute to the topic. Example: Because of the efforts of fine Americans like Frederick Douglass, countless others have seen the shining beacon of light that is education. His example was a torch that lit the way for others. Frederick Douglass was truly an American hero.

- The “Grab Bag” Conclusion. This kind of conclusion includes extra information that the writer found or thought of but couldn’t integrate into the main paper. You may find it hard to leave out details that you discovered after hours of research and thought, but adding random facts and bits of evidence at the end of an otherwise-well-organized essay can just create confusion. Example: In addition to being an educational pioneer, Frederick Douglass provides an interesting case study for masculinity in the American South. He also offers historians an interesting glimpse into slave resistance when he confronts Covey, the overseer. His relationships with female relatives reveal the importance of family in the slave community.

WORKS CONSULTED

We consulted these works while writing the original version of this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find the latest publications on this topic. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial.

All quotations are from:

Douglass, Frederick. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, edited and with introduction by Houston A. Baker, Jr., New York: Penguin Books, 1986.

Strategies for Writing a Conclusion. Literacy Education Online, St. Cloud State University. 18 May 2005

<http://leo.stcloudstate.edu/acadwrite/conclude.html>.

Conclusions. Nesbitt-Johnston Writing Center, Hamilton College. 17 May 2005 <http://www.hamilton.edu/ academic/Resource/WC/SampleConclusions.html>.

|

Licensing & Attributions CC licensed content, Shared previously Conclusions. Provided by: UNC Writing Center. Located at: http://writingcenter.unc.edu/handouts/conclusions/. License: CC BY-NC-ND: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives |

DISCUSSION: POST-DRAFT OUTLINE

A big huzzah–the rough drafts are done, which is a major hurdle. I know there’s still a lot to do, but I think the hardest part’s out of the way.

Now it’s time to turn away from the raw content creation of writing a draft, and towards the fine-tuning that does into polishing and shaping an effective essay. To start with, I’d like you to review this Post Draft Outline presentation.

Create a post-draft outline (PDO) for your own essay in its most current form. Share that PDO with us here.

After you’ve laid out the summary sentences for us to see, follow this with a short paragraph of personal response and analysis of what this activity told you. Make at least two observations of how you’ll change, add, subtract, or divide content as you move forward in the writing process.

Your posts will vary in length this week. Just make sure a full PDO is included and followed by at least a 3-sentence paragraph of observation. It doesn’t have to be grammatically perfect, but should use standard English (no text-speak, please) and normal capitalization rules.

You will also need to return to this Discussion to reply to at least two of your classmates’ posts. Content could include, but is not limited to, any of the following: Do you get a full sense of what that paper will be about? Does anything strike you as repetitive, or do you feel there is content that needs to be covered in more depth? Offer at least 2 suggestions that come out of your reflections on their post-draft outline content.

Responses are weighed as heavily as your initial posting, and should be roughly as long (150-200 words) in combination. Responses should indicate you’ve read your classmate’s post carefully. Include specific details from the post you’re responding to in your reply.

|

Licensing & Attributions CC licensed content, Shared previously Composition II. Authored by: Alexis McMillan-Clifton. Provided by: Tacoma Community College. Located at: http://www.tacomacc.edu. Project: Kaleidoscope Open Course Initiative. License: CC BY: Attribution |

ASSESSMENT: READING NOTEBOOK ENTRY #5

Review these articles about writing introductions and conclusions:

Review these articles about writing introductions and conclusions:

- Introductions: Four Types by Grammar-Quizzes

- Guide to Writing Introductions and Conclusions by Gallaudet University

After looking over those suggestions, and considering what you’ve planned for your own draft, assess your progress on opening and closing your essay so far.

Create an entry that includes any or all of the following:

- questions you had while reading these articles

- how effective you think these articles are

- how you feel about your intro/conclusion as they stand at the moment

- what relationship you see between your introduction and conclusion sections

- what strategy you plan to pursue to get your intro & conclusion in shape for the final

This is an informal assignment. Your writing can be in complete sentences, or bullet points or fragments, as you see appropriate. Editing isn’t vital for this work, though it should be proofread to the point that obvious typos or misspellings are addressed and corrected. Target word count is 150-300 words for this entry.

|

Licensing & Attributions CC licensed content, Shared previously Composition II. Authored by: Alexis McMillan-Clifton. Provided by: Tacoma Community College. Located at: http://www.tacomacc.edu. Project: Kaleidoscope Open Course Initiative. License: CC BY: Attribution Public domain content Image of notebook. Authored by: OpenClips. Provided by: Pixabay. Located at: http://pixabay.com/p-147191/?no_redirect. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright |