12

THE SEVEN STEPS OF THE RESEARCH PROCESS

The following seven steps outline a simple and effective strategy for finding information for a research paper and documenting the sources you find. Depending on your topic and your familiarity with the library, you may need to rearrange or recycle these steps. Adapt this outline to your needs. We are ready to help you at every step in your research.

STEP 1: IDENTIFY AND DEVELOP YOUR TOPIC

SUMMARY: State your topic as a question. For example, if you are interested in finding out about use of alcoholic beverages by college students, you might pose the question, “What effect does use of alcoholic beverages have on the health of college students?” Identify the main concepts or keywords in your question.

More details on how to identify and develop your topic.

STEP 2: FIND BACKGROUND INFORMATION

SUMMARY: Look up your keywords in the indexes to subject encyclopedias. Read articles in these encyclopedias to set the context for your research. Note any relevant items in the bibliographies at the end of the encyclopedia articles. Additional background information may be found in your lecture notes, textbooks, and reserve readings.

More suggestions on how to find background information.

STEP 3: USE CATALOGS TO FIND BOOKS AND MEDIA

SUMMARY: Use guided keyword searching to find materials by topic or subject. Print or write down the citation (author, title,etc.) and the location information (call number and library). Note the circulation status. When you pull the book from the shelf, scan the bibliography for additional sources. Watch for book-length bibliographies and annual reviews on your subject; they list citations to hundreds of books and articles in one subject area. Check the standard subject subheading “—BIBLIOGRAPHIES,” or titles beginning with Annual Review of… in the Cornell Library Classic Catalog.

More detailed instructions for using catalogs to find books. Finding media (audio and video) titles.

Watch this video online: https://youtu.be/R1yNDvmjqaE

STEP 4: USE INDEXES TO FIND PERIODICAL ARTICLES

SUMMARY: Use periodical indexes and abstracts to find citations to articles. The indexes and abstracts may be in print or computer-based formats or both. Choose the indexes and format best suited to your particular topic; ask at the reference desk if you need help figuring out which index and format will be best. You can find periodical articles by the article author, title, or keyword by using the periodical indexes in theLibrary home page. If the full text is not linked in the index you are using, write down the citation from the index and search for the title of the periodical in the Cornell Library Classic Catalog. The catalog lists the print, microform, and electronic versions of periodicals at Cornell.

How to find and use periodical indexes at Cornell.

STEP 5: FIND INTERNET RESOURCES

SUMMARY: Use search engines. Check to see if your class has a bibliography or research guide created by librarians.

Finding Information on the Internet: A thorough tutorial from UC Berkeley.

STEP 6: EVALUATE WHAT YOU FIND

SUMMARY: See How to Critically Analyze Information Sources and Distinguishing Scholarly from Non-Scholarly Periodicals: A Checklist of Criteria for suggestions on evaluating the authority and quality of the books and articles you located.

Watch this video online: https://youtu.be/uDGJ2CYfY9A Watch this video online: https://youtu.be/QAiJL5B5esM

If you have found too many or too few sources, you may need to narrow or broaden your topic. Check with a reference librarian or your instructor. When you’re ready to write, here is an annotated list of books to help you organize, format, and write your paper.

STEP 7: CITE WHAT YOU FIND USING A STANDARD FORMAT

Give credit where credit is due; cite your sources.

Citing or documenting the sources used in your research serves two purposes, it gives proper credit to the authors of the materials used, and it allows those who are reading your work to duplicate your research and locate the sources that you have listed as references.

Knowingly representing the work of others as your own is plagarism. (See Cornell’s Code of Academic Integrity). Use one of the styles listed below or another style approved by your instructor. Handouts summarizing the APA and MLA styles are available at Uris and Olin Reference.

Available online:

RefWorks is a web-based program that allows you to easily collect, manage, and organize bibliographic references by interfacing with databases. RefWorks also interfaces directly with Word, making it easy to import references and incorporate them into your writing, properly formatted according to the style of your choice.

See our guide to citation tools and styles.

Format the citations in your bibliography using examples from the following Library help pages: Modern Language Association (MLA) examples and American Psychological Association (APA) examples.

- Style guides in print (book) format:

- MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers. 7th ed. New York: MLA, 2009. This handbook is based on the MLA Style Manual and is intended as an aid for college students writing research papers. Included here is information on selecting a topic, researching the topic, note taking, the writing of footnotes and bibliographies, as well as sample pages of a research paper. Useful for the beginning researcher.

- Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association. 6th ed. Washington: APA, 2010. The authoritative style manual for anyone writing in the field of psychology. Useful for the social sciences generally. Chapters discuss the content and organization of a manuscript, writing style, the American Psychological Association citation style, and typing, mailing and proofreading.

If you are writing an annotated bibliography, see How to Prepare an Annotated Bibliography.

RESEARCH TIPS:

- WORK FROM THE GENERAL TO THE SPECIFIC. Find background information first, then use more specific and recent sources.

- RECORD WHAT YOU FIND AND WHERE YOU FOUND IT. Record the complete citation for each source you find; you may need it again later.

- TRANSLATE YOUR TOPIC INTO THE SUBJECT LANGUAGE OF THE INDEXES AND CATALOGS YOU USE. Check your topic words against a thesaurus or subject heading list.

|

Licensing & Attributions CC licensed content, Shared previously The Seven Steps. Provided by: Research & Learning Services Olin Library Cornell University Library Ithaca, NY, USA. Located at: http://guides.library.cornell.edu/sevensteps. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike. License Terms: Lumen Learning has received permission from Olin & Uris Libraries to reproduce this and adapt it for our own use Research Minutes: How to Identify Scholarly Journal Articles. Authored by: Olin & Uris Libraries, Cornell University. Located at: https://youtu.be/uDGJ2CYfY9A. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube License All rights reserved content Research Minutes: How to Read Citations. Authored by: Olin & Uris Libraries, Cornell University. Located at: https://youtu.be/R1yNDvmjqaE. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube License Research Minutes: How to Identify Substantive News Articles. Authored by: Olin & Uris Libraries, Cornell University. Located at: https://youtu.be/QAiJL5B5esM. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube License |

UNDERSTANDING BIAS

Bias

Bias

Bias means presenting facts and arguments in a way that consciously favours one side or other in an argument. Is bias bad or wrong?

No! Everyone who argues strongly for something is biased. So it’s not enough, when you are doing a language analysis, to merely spot some bias and say…”This writer is biased” or “This speaker is biased.”

Let’s begin by reading a biased text.

|

Hypocrites gather to feed off Daniel’s tragic death The death of two-year-old Daniel Valerio at the hands of his step-father brought outrage from the media. Daniel suffered repeated beatings before the final attack by Paul Alton, who was sentenced in Melbourne in February to 22 years jail. |

|

Rupert Murdoch’s Herald-Sun launched a campaign which included a public meeting of hundreds of readers. Time magazine put Daniel on its front cover. The Herald-Sun summed up their message: The community has a duty to protect our children from abuse – if necessary by laws that some people regard as possibly harsh or unnecessary. But laws – like making it compulsory for doctors and others to report suspected abuse – cannot stop the violence. Last year, 30 children were murdered across Australia. Babies under one are more likely to be killed than any other social group. Daniel’s murder was not a horrific exception but the product of a society that sends some of its members over the edge into despairing violence. The origin of these tragedies lies in the enormous pressures on families, especially working class families. The media and politicians wring their hands over a million unemployed. But they ignore the impact that having no job, or a stressful poorly paid job, can have. Child abuse can happen in wealthy families. But generally it is linked to poverty. A survey in 1980 of “maltreating families” showed that 56.5 per cent were living in poverty and debt. A further 20 per cent expressed extreme anxiety about finances. A study in Queensland found that all the children who died from abuse came from working class families. Police records show that school holidays – especially Xmas – are peak times for family violence. “The sad fact is that when families are together for longer than usual, there tends to be more violence”, said one Victorian police officer. Most people get by. Family life may get tense, but not violent. But a minority cannot cope and lash out at the nearest vulnerable person to hand – an elderly person, a woman, or a child. Compulsory reporting of child abuse puts the blame on the individual parents rather than the system that drives them to this kind of despair. Neither is it a solution. Daniel was seen by 21 professionals before he was killed. Nonetheless, the Victorian Liberal government has agreed to bring it in. Their hypocrisy is breathtaking. This is the same government that is sacking 250 fire-fighters, a move that will lead to more deaths. A real challenge to the basis of domestic violence means a challenge to poverty. Yet which side were the media on when Labor cut the under-18 dole, or when Jeff Kennett[1] added $30 a week to the cost of sending a child to kindergarten? To really minimise family violence, we need a fight for every job and against every cutback. – by David Glanz, The Socialist, April 1993 |

There are good and bad aspects of bias.

- It is good to be open about one’s bias. For example, the article about Daniel Valerio’s tragic death is written for The Socialist newspaper. Clearly socialists will have a bias against arguments that blame only the individual for a crime when it could be argued that many other factors in society contributed to the crime and need to be changed. Focusing on the individual, from the socialist’s point of view, gets “the system” off the hook when crimes happen. The socialist’s main reason for writing is to criticise the capitalist system. So David Glanz is not pretending to not be biased, because he has published his article in a partisan[2] newspaper.

- Here are some ways to be open about your bias, but still be naughty.

- (a) Deliberately avoid mentioning any of the opposing arguments.

- (b) Deliberately avoid mentioning relevant facts or information that would undermine your own case.

- (c) Get into hyperbole.

- (d) Make too much use of emotive language.

- (e) Misuse or distort statistics.

- (f) Use negative adjectives when talking about people you disagree with, but use positive adjectives when talking about people you agree with.

- Can you find examples of any of these “naughty” ways to be biased in Glaz’s article?

- You mustn’t assume that because a person writes with a particular bias he/she is not being sincere, or that he/she has not really thought the issue through. The person is not just stating what he/she thinks, he/she is trying to persuade you about something.

Bias can result from the way you have organised your experiences in your own mind. You have lumped some experiences into the ‘good’ box and some experiences into the ‘bad’ box. Just about everybody does this[3]. The way you have assembled and valued experiences in your mind is called your Weltanschauung (Velt-arn-shao- oong). If through your own experience, plus good thinking about those experiences, you have a better understanding of something, your bias is indeed a good thing.

For example, if you have been a traffic policeman, and have seen lots of disasters due to speed and alcohol, it is not ‘wrong’ for you to biased against fast cars and drinking at parties and pubs. Your bias is due to your better understanding of the issue, but you still have to argue logically.

- If you pretend to be objective, to not take sides, but actually use techniques that tend to support one side of an argument, in that case you are being naughty. There are subtle ways to do this.

- If the support for one side of the argument is mainly at the top of the article, and the reasons to support the opposite side of the issue are mainly at the bottom end of the article; that might be subtle bias – especially if it was written by a journalist. Journalists are taught that many readers only read the first few paragraphs of an article before moving on to reading another article, so whatever is in the first few paragraphs will be what sticks in the reader’s mind.

- Quotes from real people are stronger emotionally than just statements by the writer. This is especially true if the person being quoted is an ‘authority’ on the subject, or a ‘celebrity’. So if one side of the issue is being supported by lots of quotes, and the other side isn’t, that is a subtle form of bias.

- If when one person is quoted as saying X, but the very next sentence makes that quote sound silly or irrational, that is a subtle form of bias too.

Common sense tells us that if someone is making money out of something, he/she will be biased in favour of it.

For example, a person who makes money out of building nuclear reactors in Europe or China could be expected to support a change in policy in Australia towards developing nuclear energy.

A manufacturer of cigarettes is unlikely to be in favour of health warnings on cigarette packets or bans on smoking in pubs.

A manufacturer of cigarettes is unlikely to be in favour of health warnings on cigarette packets or bans on smoking in pubs.

Nonetheless, logically speaking, we cannot just assume a person who is making money out of something will always take sides with whomever or whatever will make him/her more money.

We have to listen to the arguments as they come up. Assuming someone is biased is not logically okay. You have to show that someone is biased and use evidence to support your assertion that he/she is biased.

- Jeff Kennett was the leader of the Liberal party in Victoria at that time.

- When you are a partisan you have taken sides in an argument, or a battle, or a war.

- Learning critical thinking (which is what you are learning in Year 11 and 12 English) is aimed at getting you to do more, and better, thinking than that.

|

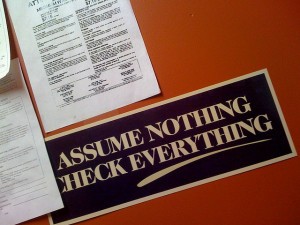

Licensing & Attributions CC licensed content, Shared previously Image of Bias. Authored by: Franco Folini. Located at: https://flic.kr/p/jFQwC. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike Image of Assume Nothing. Authored by: David Gallagher. Located at: https://flic.kr/p/5wZECN. License: CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial Public domain content Bias. Authored by: nenifoofer. Located at: http://www.docstoc.com/docs/4644737/Understanding%20Bias. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright |

EXAMPLES FOR READING NOTEBOOK #4

Example #1 Research project’s topic is “Whistleblowing & the NSA Security Leaks” https://docs.google.com/document/d/1jlrlxKk-9FJJXo0ZC4mql_ps1hQymtzrlAKhlVL6D0o/edit?usp=sharing Example #2 Research project’s topic is “China’s One-Child Policy”

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1Bb9OebRI-LGyzMFdAOdEEOx5wAb3LNTrBxsa6xE9qNY/ edit?usp=sharing

|

Licensing & Attributions CC licensed content, Shared previously Composition II. Authored by: Alexis McMillan-Clifton. Provided by: Tacoma Community College. Located at: http://www.tacomacc.edu. Project: Kaleidoscope Open Course Initiative. License: CC BY: Attribution |

ASSESSMENT: INVESTIGATING YOUR SOURCE

For the source you’ve chosen—and it can be anything that relates to your final research essay topic—complete the following questionnaire. It’s important to note that not all of these answers may prove helpful to actually drafting the Evaluation Essay. Instead, you’re brainstorming possible content for that essay, and then picking what seems to be the most important features about your source from this initial exploration.

Source Evaluation Questionnaire

Title of Source:

How you found it:

- Who wrote/presented this information? (If not an individual, who is responsible for publishing it?) Do a websearch on this individual or group. What do you learn?

- Where was this source published or made available? What other types of articles, etc., does this publication have on offer?

- Note one particular fact or bit of data that is included, here. Try to verify this fact by checking other sources. What do you learn?

- Does the author seem to have any bias? In what way? Why do you suspect this? (Review the Understanding Bias page to help.)

- Does the source publication have any bias? In what way? Why do you suspect this?

- What is this source’s thesis or prevailing idea?

- How does this source promote this main idea? In other words, how does it support its argument?

- What does this source’s primary audience seem to be? How do you know?

- What is its primary rhetorical mode (logic, emotion, ethics)?

- Does this source support, oppose, or remain neutral on your own paper’s thesis?

|

Licensing & Attributions CC licensed content, Original Composition II. Authored by: Alexis McMillan-Clifton. Provided by: Tacoma Community College. Located at: http://www.tacomacc.edu. Project: Kaleidoscope Open Course Initiative. License: CC BY: Attribution |