14

According to Lunsford and Ruszkiewicz, “an academic argument covers a wide range of writing, but its hallmarks are an appeal to reason and a reliance on research. As a consequence, such arguments cannot be composed quickly, casually, or off the top of one’s head. They require careful reading, accurate reporting, and a conscientious commitment to truth. But academic pieces do not tune out all appeals to ethos or emotion: today, we know that these arguments often convey power and authority through their impressive lists of sources and their immediacy. But an academic argument crumbles if its facts are skewed or its content proves to be unreliable” (406).

In writing for academic purposes it’s important to understand how arguments can be organized or structured because your arguments need to use specific strategies that convey your claims, assumptions, evidence, counterarguments and audience to be effective. The following information are ways that arguments can be organized.

ROGERIAN ARGUMENT

The Rogerian argument, inspired by the influential psychologist Carl Rogers, aims to find compromise on a controversial issue. If you are using the Rogerian approach your introduction to the argument should accomplish three objectives:

Introduce the author and work

Usually, you will introduce the author and work in the first sentence, as in this example:In Dwight Okita’s “In Response to Executive Order 9066,” the narrator addresses an inevitable by-product of war – racism.The first time you refer to the author, refer to him or her by his or her full name. After that, refer to the author by last name only. Never refer to an author by his or her first name only.

Provide the audience a short but concise summary of the work to which you are responding

Remember, your audience has already read the work you are responding to. Therefore, you do not need to provide a lengthy summary. Focus on the main points of the work to which you are responding and use direct quotations sparingly. Direct quotations work best when they are powerful and compelling.

Carl Rogers

- State the main issue addressed in the work Your thesis, or claim, will come after you summarize the two sides of the issue.

The Introduction

The following is an example of how the introduction of a Rogerian argument can be written. The topic is racial profiling.

|

In Dwight Okita’s “In Response to Executive Order 9066,” the narrator — a young Japanese-American — writes a letter to the government, who has ordered her family into a relocation camp after Pearl Harbor. In the letter, the narrator details the people in her life, from her father to her best friend at school. Since the narrator is of Japanese descent, her best friend accuses her of “trying to start a war” (18). The narrator is seemingly too naïve to realize the ignorance of this statement, and tells the government that she asked this friend to plant tomato seeds in her honor. Though Okita’s poem deals specifically with World War II, the issue of race relations during wartime is still relevant. Recently, with the outbreaks of terrorism in the United States, Spain, and England, many are calling for racial profiling to stifle terrorism. The issue has sparked debate, with one side calling it racism and the other calling it common sense. |

Once you have written your introduction, you must now show the two sides to the debate you are addressing. Though there are always more than two sides to a debate, Rogerian arguments put two in stark opposition to one another. Summarize each side, then provide a middle path. Your summary of the two sides will be your first two body paragraphs. Use quotations from outside sources to effectively illustrate the position of each side.

An outline for a Rogerian argument might look like this:

- Introduction

- Side A

- Side B

- Claim

- Conclusion

The Claim

Since the goal of Rogerian argument is to find a common ground between two opposing positions, you must identify the shared beliefs or assumptions of each side. In the example above, both sides of the racial profiling issue want the U.S. A solid Rogerian argument acknowledges the desires of each side, and tries to accommodate both. Again, using the racial profiling example above, both sides desire a safer society, perhaps a better solution would focus on more objective measures than race; an effective start would be to use more screening technology on public transportation. Once you have a claim that disarms the central dispute, you should support the claim with evidence, and quotations when appropriate.

Quoting Effectively

Remember, you should quote to illustrate a point you are making. You should not, however, quote to simply take up space. Make sure all quotations are compelling and intriguing: Consider the following example. In “The Danger of Political Correctness,” author Richard Stein asserts that, “the desire to not offend has now become more important than protecting national security” (52). This statement sums up the beliefs of those in favor of profiling in public places.

The Conclusion

Your conclusion should:

- Bring the essay back to what is discussed in the introduction

- Tie up loose ends

- End on a thought-provoking note

The following is a sample conclusion:

|

Though the debate over racial profiling is sure to continue, each side desires to make the United States a safer place. With that goal in mind, our society deserves better security measures than merely searching a person who appears a bit dark. We cannot waste time with such subjective matters, especially when we have technology that could more effectively locate potential terrorists. Sure, installing metal detectors and cameras on public transportation is costly, but feeling safe in public is priceless. |

|

CC licensed content, Shared previously Rogerian Argument. Provided by: Utah State University. Located at: http://ocw.usu.edu/English/introduction-to-writing-academic-prose/rogerian-argument.html. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial- ShareAlike Image of Carl Rogers. Authored by: Didius. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Carl_Ransom_Rogers.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution |

TOULMIN’S ARGUMENT MODEL

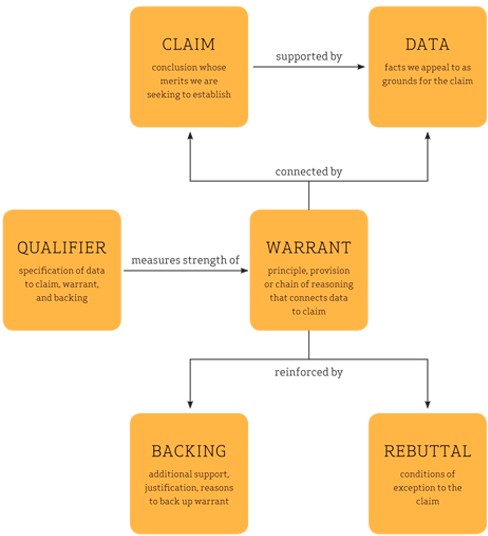

Stephen Toulmin, an English philosopher and logician, identified elements of a persuasive argument. These give useful categories by which an argument may be analyzed.

Claim

A claim is a statement that you are asking the other person to accept. This includes information you are asking them to accept as true or actions you want them to accept and enact.

For example:

You should use a hearing aid.

Many people start with a claim, but then find that it is challenged. If you just ask me to do something, I will not simply agree with what you want. I will ask why I should agree with you. I will ask you to prove your claim. This is where grounds become important.

Grounds

The grounds (or data) is the basis of real persuasion and is made up of data and hard facts, plus the reasoning behind the claim. It is the ‘truth’ on which the claim is based. Grounds may also include proof of expertise and the basic premises on which the rest of the argument is built.

The actual truth of the data may be less that 100%, as much data are ultimately based on perception. We assume what we measure is true, but there may be problems in this measurement, ranging from a faulty measurement instrument to biased sampling.

It is critical to the argument that the grounds are not challenged because, if they are, they may become a claim, which you will need to prove with even deeper information and further argument.

For example:

Over 70% of all people over 65 years have a hearing difficulty.

Information is usually a very powerful element of persuasion, although it does affect people differently. Those who are dogmatic, logical or rational will more likely to be persuaded by factual data. Those who argue emotionally and who are highly invested in their own position will challenge it or otherwise try to ignore it. It is often a useful test to give something factual to the other person that disproves their argument, and watch how they handle it.

Some will accept it without question. Some will dismiss it out of hand. Others will dig deeper, requiring more explanation. This is where the warrant comes into its own.

Warrant

A warrant links data and other grounds to a claim, legitimizing the claim by showing the grounds to be relevant. The warrant may be explicit or unspoken and implicit. It answers the question ‘Why does that data mean your claim is true?’

For example:

A hearing aid helps most people to hear better.

The warrant may be simple and it may also be a longer argument, with additional sub–elements including those described below.

Warrants may be based on logos, ethos or pathos, or values that are assumed to be shared with the listener.

In many arguments, warrants are often implicit and hence unstated. This gives space for the other person to question and expose the warrant, perhaps to show it is weak or unfounded.

Backing

The backing (or support) for an argument gives additional support to the warrant by answering different questions. For example:

Hearing aids are available locally.

Qualifier

The qualifier (or modal qualifier) indicates the strength of the leap from the data to the warrant and may limit how universally the claim applies. They include words such as ‘most’, ‘usually’, ‘always’ or ‘sometimes’. Arguments may hence range from strong assertions to generally quite floppy with vague and often rather uncertain kinds of statement.

For example:

Hearing aids help most people.

Another variant is the reservation, which may give the possibility of the claim being incorrect. Unless there is evidence to the contrary, hearing aids do no harm to ears.

Qualifiers and reservations are much used by advertisers who are constrained not to lie. Thus they slip ‘usually’, ‘virtually’, ‘unless’ and so on into their claims.

Rebuttal

Despite the careful construction of the argument, there may still be counter-arguments that can be used. These may be rebutted either through a continued dialogue, or by pre-empting the counter-argument by giving the rebuttal during the initial presentation of the argument.

For example:

There is a support desk that deals with technical problems.

Any rebuttal is an argument in itself, and thus may include a claim, warrant, backing and so on. It also, of course can have a rebuttal. Thus if you are presenting an argument, you can seek to understand both possible rebuttals and also rebuttals to the rebuttals.

See also:

Arrangement, Use of Language

Toulmin, S. (1969). The Uses of Argument, Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press

<http://changingminds.org/disciplines/argument/making_argument/toulmin.htm > [accessed April 2011]

See more at: http://www.designmethodsandprocesses.co.uk/2011/03/toulmins-argument- model/#sthash.dwkAUTvh.dpuf

|

Licensing & Attributions CC licensed content, Shared previously Toulmin’s Argument Model. Provided by: Metapatterns. Located at: http://www.designmethodsandprocesses.co.uk/2011/03/toulmins-argument-model/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike |

TOULMIN’S SCHEMA

Stephen Edelston Toulmin (born March 25, 1922) is a British philosopher, author, and educator. Influenced by the Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, Toulmin devoted his works to the analysis of moral reasoning.

Throughout his writings, he seeks to develop practical arguments which can be used effectively in evaluating the ethics behind moral issues. The Toulmin Model of Argumentation, a diagram containing six interrelated components used for analyzing arguments, was considered his most influential work, particularly in the field of rhetoric and communication, and in computer science.

Stephen Toulmin is a British philosopher and educator who devoted to analyzing moral reasoning. Throughout his writings, he seeks to develop practical arguments which can be used effectively in evaluating the ethics behind moral issues. His most famous work was his Model of Argumentation(sometimes called “Toulmin’s Schema,” which is a method of analyzing an argument by breaking it down into six parts. Once an argument is broken down and examined, weaknesses in the argument can be found and addressed.

Toulmin’s Schema:

- Claim: conclusions whose merit must be established. For example, if a person tries to convince a listener that he is a British citizen, the claim would be “I am a British citizen.”

- Data: the facts appealed to as a foundation for the claim. For example, the person introduced in 1 can support his claim with the supporting data “I was born in Bermuda.”

- Warrant: the statement authorizing the movement from the data to the claim. In order to move from the data established in 2, “I was born in Bermuda,” to the claim in 1, “I am a British citizen,” the person must supply a warrant to bridge the gap between 1 & 2 with the statement “A man born in Bermuda will legally be a British Citizen.” Toulmin stated that an argument is only as strong as its weakest warrant and if a warrant isn’t valid, then the whole argument collapses. Therefore, it is important to have strong, valid warrants.

- Backing: facts that give credibility to the statement expressed in the warrant; backing must be introduced when the warrant itself is not convincing enough to the readers or the listeners. For example, if the listener does not deem the warrant as credible, the speaker would supply legal documents as backing statement to show that it is true that “A man born in Bermuda will legally be a British Citizen.”

- Rebuttal: statements recognizing the restrictions to which the claim may legitimately be applied. The rebuttal is exemplified as follows, “A man born in Bermuda will legally be a British citizen, unless he has betrayed Britain and become a spy of another country.”

- Qualifier: words or phrases expressing how certain the author/speaker is concerning the claim. Such words or phrases include “possible,” “probably,” “impossible,” “certainly,” “presumably,” “as far as the evidence goes,” or “necessarily.” The claim “I am definitely a British citizen” has a greater degree of force than the claim “I am a British citizen, presumably.”

- The first three elements “claim,” “data,” and “warrant” are considered as the essential components of practical arguments, while the 4-6 “Qualifier,” “Backing,” and “Rebuttal” may not be needed in some arguments. When first proposed, this layout of argumentation is based on legal arguments and intended to be used to analyze arguments typically found in the courtroom; in fact, Toulmin did not realize that this layout would be applicable to the field of rhetoric and communication until later. 1

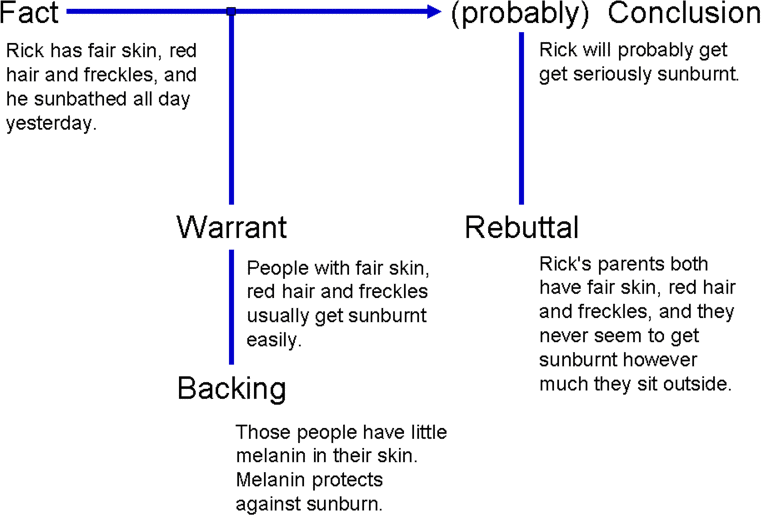

Here are a few more examples of Toulmin’s Schema:

Suppose you see a one of those commercials for a product that promises to give you whiter teeth. Here are the basic parts of the argument behind the commercial:

- Claim: You should buy our tooth-whitening product.

- Data: Studies show that teeth are 50% whiter after using the product for a specified time.

- Warrant: People want whiter teeth.

- Backing: Celebrities want whiter teeth.

- Rebuttal: Commercial says “unless you don’t want to attract guys.”

- Qualifier: Fine print says “product must be used six weeks for results.”

Notice that those commercials don’t usually bother trying to convince you that you want whiter teeth; instead, they assume that you have bought into the value our culture places on whiter teeth. When an assumption–a warrant in Toulmin’s terms–is unstated, it’s called an implicit warrant.

Sometimes, however, the warrant may need to be stated because it is a powerful part of the argument. When the warrant is stated, it’s called an explicit warrant. 2

Another example:

- Claim: People should probably own a gun.

- Data: Studies show that people who own a gun are less likely to be mugged.

- Warrant: People want to be safe.

- Backing: May not be necessary. In this case, it is common sense that peoplewant to be safe.

- Rebuttal: Not everyone should own a gun. Children and those will mentaldisorders/problems should not own a gun.

- Qualifier: The word “probably” in the claim.

- Claim: Flag burning should be unconstitutional in most cases.

- Data: A national poll says that 60% of Americans want flag burningunconstitutional

- Warrant: People want to respect the flag.

- Backing: Official government procedures for the disposal of flags.

- Rebuttal: Not everyone in the U.S. respects the flag.

- Qualifier: The phrase “in most cases”

Toulmin says that the weakest part of any argument is its weakest warrant. Remember that the warrant is the link between the data and the claim. If the warrant isn’t valid, the argument collapses. 2

Sources

|

Licensing & Attributions CC licensed content, Shared previously Toulmin’s Schema. Provided by: Utah State University OpenCourseWare. Located at: http://ocw.usu.edu/english/intermediate-writing/english-2010/-2010/toulmins-schema.html. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike Image of flowchart. Authored by: Chiswick Chap. Located at: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Toulmin_Argumentation_Example.gif. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike Image of woman with white teeth. Authored by: Harsha K R. Located at: https://flic.kr/p/5s24kK. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike |

PERSUASION

The Purpose of Persuasive Writing

The purpose of persuasion in writing is to convince, motivate, or move readers toward a certain point of view, or opinion. The act of trying to persuade automatically implies more than one opinion on the subject can be argued.

The idea of an argument often conjures up images of two people yelling and screaming in anger. In writing, however, an argument is very different. An argument is a reasoned opinion supported and explained by evidence. To argue in writing is to advance knowledge and ideas in a positive way. Written arguments often fail when they employ ranting rather than reasoning.

|

Tip Most of us feel inclined to try to win the arguments we engage in. On some level, we all want to be right, and we want others to see the error of their ways. More times than not, however, arguments in which both sides try to win end up producing losers all around. The more productive approach is to persuade your audience to consider your opinion as a valid one, not simply the right one. |

The Structure of a Persuasive Essay

The following five features make up the structure of a persuasive essay:

- Introduction and thesis

- Opposing and qualifying ideas

- Strong evidence in support of claim

- Style and tone of language

- A compelling conclusion

Creating an Introduction and Thesis

The persuasive essay begins with an engaging introduction that presents the general topic. The thesis typically appears somewhere in the introduction and states the writer’s point of view.

|

Tip Avoid forming a thesis based on a negative claim. For example, “The hourly minimum wage is not high enough for the average worker to live on.” This is probably a true statement, but persuasive arguments should make a positive case. That is, the thesis statement should focus on how the hourly minimum wage is low or insufficient. |

Acknowledging Opposing Ideas and Limits to Your Argument

Because an argument implies differing points of view on the subject, you must be sure to acknowledge those opposing ideas. Avoiding ideas that conflict with your own gives the reader the impression that you may be uncertain, fearful, or unaware of opposing ideas. Thus it is essential that you not only address counterarguments but also do so respectfully.

Try to address opposing arguments earlier rather than later in your essay. Rhetorically speaking, ordering your positive arguments last allows you to better address ideas that conflict with your own, so you can spend the rest of the essay countering those arguments. This way, you leave your reader thinking about your argument rather than someone else’s. You have the last word.

Acknowledging points of view different from your own also has the effect of fostering more credibility between you and the audience. They know from the outset that you are aware of opposing ideas and that you are not afraid to give them space.

It is also helpful to establish the limits of your argument and what you are trying to accomplish. In effect, you are conceding early on that your argument is not the ultimate authority on a given topic. Such humility can go a long way toward earning credibility and trust with an audience. Audience members will know from the beginning that you are a reasonable writer, and audience members will trust your argument as a result. For example, in the following concessionary statement, the writer advocates for stricter gun control laws, but she admits it will not solve all of our problems with crime:

Although tougher gun control laws are a powerful first step in decreasing violence in our streets, such legislation alone cannot end these problems since guns are not the only problem we face.

Such a concession will be welcome by those who might disagree with this writer’s argument in the first place. To effectively persuade their readers, writers need to be modest in their goals and humble in their approach to get readers to listen to the ideas. See Table 10.5 “Phrases of Concession” for some useful phrases of concession.

Table 10.5 Phrases of Concession

|

although |

granted that |

|

of course |

still |

|

though |

yet |

|

Exercise 1 |

|

Try to form a thesis for each of the following topics. Remember the more specific your thesis, the better. Foreign policy Television and advertising Stereotypes and prejudice Gender roles and the workplace Driving and cell phones Collaboration Please share with a classmate and compare your answers. Choose the thesis statement that most interests you and discuss why. |

Bias in Writing

Everyone has various biases on any number of topics. For example, you might have a bias toward wearing black instead of brightly colored clothes or wearing jeans rather than formal wear. You might have a bias toward working at night rather than in the morning, or working by deadlines rather than getting tasks done in advance.

These examples identify minor biases, of course, but they still indicate preferences and opinions.

Handling bias in writing and in daily life can be a useful skill. It will allow you to articulate your own points of view while also defending yourself against unreasonable points of view. The ideal in persuasive writing is to let your reader know your bias, but do not let that bias blind you to the primary components of good argumentation: sound, thoughtful evidence and a respectful and reasonable address of opposing sides.

The strength of a personal bias is that it can motivate you to construct a strong argument. If you are invested in the topic, you are more likely to care about the piece of writing. Similarly, the more you care, the more time and effort you are apt to put forth and the better the final product will be.

The weakness of bias is when the bias begins to take over the essay—when, for example, you neglect opposing ideas, exaggerate your points, or repeatedly insert yourself ahead of the subject by using I too often. Being aware of all three of these pitfalls will help you avoid them.

The Use of I in Writing

The use of I in writing is often a topic of debate, and the acceptance of its usage varies from instructor to instructor. It is difficult to predict the preferences for all your present and future instructors, but consider the effects it can potentially have on your writing.

Be mindful of the use of I in your writing because it can make your argument sound overly biased. There are two primary reasons:

- Excessive repetition of any word will eventually catch the reader’s attention—and usually not in a good way. The use of I is no different.

- The insertion of I into a sentence alters not only the way a sentence might sound but also the composition of the sentence itself. I is often the subject of a sentence. If the subject of the essay is supposed to be, say, smoking, then by inserting yourself into the sentence, you are effectively displacing the subject of the essay into a secondary position. In the following example, the subject of the sentence is underlined:

Smoking is bad.

I think smoking is bad.

In the first sentence, the rightful subject, smoking, is in the subject position in the sentence. In the second sentence, the insertion of I and think replaces smoking as the subject, which draws attention to I and away from the topic that is supposed to be discussed. Remember to keep the message (the subject) and the messenger (the writer) separate.

Checklist

Developing Sound Arguments

Does my essay contain the following elements?

- An engaging introduction

- A reasonable, specific thesis that is able to be supported by evidence

- A varied range of evidence from credible sources

- Respectful acknowledgement and explanation of opposing ideas

- A style and tone of language that is appropriate for the subject and audience

- Acknowledgement of the argument’s limits

- A conclusion that will adequately summarize the essay and reinforce the thesis

Fact and Opinion

Facts are statements that can be definitely proven using objective data. The statement that is a fact is absolutely valid. In other words, the statement can be pronounced as true or false. For example, 2 + 2 = 4. This expression identifies a true statement, or a fact, because it can be proved with objective data.

Opinions are personal views, or judgments. An opinion is what an individual believes about a particular subject. However, an opinion in argumentation must have legitimate backing; adequate evidence and credibility should support the opinion. Consider the credibility of expert opinions. Experts in a given field have the knowledge and credentials to make their opinion meaningful to a larger audience.

For example, you seek the opinion of your dentist when it comes to the health of your gums, and you seek the opinion of your mechanic when it comes to the maintenance of your car. Both have knowledge and credentials in those respective fields, which is why their opinions matter to you. But the authority of your dentist may be greatly diminished should he or she offer an opinion about your car, and vice versa.

In writing, you want to strike a balance between credible facts and authoritative opinions. Relying on one or the other will likely lose more of your audience than it gains.

|

Tip The word prove is frequently used in the discussion of persuasive writing. Writers may claim that one piece of evidence or another proves the argument, but proving an argument is often not possible. No evidence proves |

|

a debatable topic one way or the other; that is why the topic is debatable. Facts can be proved, but opinions can only be supported, explained, and persuaded. |

|

Exercise 2 |

|

On a separate sheet of paper, take three of the theses you formed in Note 10.94 “Exercise 1”, and list the types of evidence you might use in support of that thesis. |

|

Using the evidence you provided in support of the three theses in Note 10.100 “Exercise 2”, come up with at least one counterargument to each. Then write a concession statement, expressing the limits to each of your three arguments. |

Using Visual Elements to Strengthen Arguments

Adding visual elements to a persuasive argument can often strengthen its persuasive effect. There are two main types of visual elements: quantitative visuals and qualitative visuals.

Quantitative visuals present data graphically. They allow the audience to see statistics spatially. The purpose of using quantitative visuals is to make logical appeals to the audience. For example, sometimes it is easier to understand the disparity in certain statistics if you can see how the disparity looks graphically. Bar graphs, pie charts, Venn diagrams, histograms, and line graphs are all ways of presenting quantitative data in spatial dimensions.

Qualitative visuals present images that appeal to the audience’s emotions. Photographs and pictorial images are examples of qualitative visuals. Such images often try to convey a story, and seeing an actual example can carry more power than hearing or reading about the example. For example, one image of a child suffering from malnutrition will likely have more of an emotional impact than pages dedicated to describing that same condition in writing.

|

Writing at Work |

|

When making a business presentation, you typically have limited time to get across your idea. Providing visual elements for your audience can be an effective timesaving tool. Quantitative visuals in business presentations serve the same purpose as they do in persuasive writing. They should make logical appeals by showing numerical data in a spatial design. Quantitative visuals should be pictures that might appeal to your audience’s emotions. You will find that many of the rhetorical devices used in writing are the same ones used in the workplace. For more information about visuals in presentations, see Chapter 14 “Creating Presentations: Sharing Your Ideas.” |

Writing a Persuasive Essay

Choose a topic that you feel passionate about. If your instructor requires you to write about a specific topic, approach the subject from an angle that interests you. Begin your essay with an engaging introduction. Your thesis should typically appear somewhere in your introduction.

Start by acknowledging and explaining points of view that may conflict with your own to build credibility and trust with your audience. Also state the limits of your argument. This too helps you sound more reasonable and honest to those who may naturally be inclined to disagree with your view. By respectfully acknowledging opposing arguments and conceding limitations to your own view, you set a measured and responsible tone for the essay.

Make your appeals in support of your thesis by using sound, credible evidence. Use a balance of facts and opinions from a wide range of sources, such as scientific studies, expert testimony, statistics, and personal anecdotes. Each piece of evidence should be fully explained and clearly stated.

Make sure that your style and tone are appropriate for your subject and audience. Tailor your language and word choice to these two factors, while still being true to your own voice.

Finally, write a conclusion that effectively summarizes the main argument and reinforces your thesis. See Chapter 15 “Readings: Examples of Essays” to read a sample persuasive essay.

|

Exercise 4 |

|

Choose one of the topics you have been working on throughout this section. Use the thesis, evidence, opposing argument, and concessionary statement as the basis for writing a full persuasive essay. Be sure to include an engaging introduction, clear explanations of all the evidence you present, and a strong conclusion. |

|

The purpose of persuasion in writing is to convince or move readers toward a certain point of view, or opinion. An argument is a reasoned opinion supported and explained by evidence. To argue, in writing, is to advance knowledge and ideas in a positive way. A thesis that expresses the opinion of the writer in more specific terms is better than one that is vague. It is essential that you not only address counterarguments but also do so respectfully. It is also helpful to establish the limits of your argument and what you are trying to accomplish through a concession statement. To persuade a skeptical audience, you will need to use a wide range of evidence. Scientific studies, opinions from experts, historical precedent, statistics, personal anecdotes, and current events are all types of evidence that you might use in explaining your point. Make sure that your word choice and writing style is appropriate for both your subject and your audience. You should let your reader know your bias, but do not let that bias blind you to the primary components of good argumentation: sound, thoughtful evidence and respectfully and reasonably addressing opposing ideas. You should be mindful of the use of I in your writing because it can make your argument sound more biased than it needs to. Facts are statements that can be proven using objective data. Opinions are personal views, or judgments, that cannot be proven. In writing, you want to strike a balance between credible facts and authoritative opinions. Quantitative visuals present data graphically. The purpose of using quantitative visuals is to make logical appeals to the audience. Qualitative visuals present images that appeal to the audience’s emotions. |

|

Source: Lunsford, Andrea A., and John J. Ruszkiewicz. Everything’s an Argument. 8th ed., Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2019.

Licensing & Attributions CC licensed content, Shared previously Successful Writing. Authored by: Anonymous. Provided by: Anonymous. Located at: http://2012books.lardbucket.org/books/successful-writing/. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike |