Dr. Carol Williams and joerdis

Like most historians Dr. Carol Williams uses Open Access materials and OER out of the desire to use primary resources in the classroom. She curates them in themed modules, for which she accesses a vast array of digital resources. Adopting Open Pedagogy has broadened the scope of what she can do in the classroom.

This interview is based on a conversation with Dr. Williams in May 2017.

Teaching Centre (TC): What is your connection to Open Educational Resources and other freely accessible digital teaching materials?

I am a historian with an arts background, and my research is based on the analysis of visual images, which explains why I need primary sources for my work. In a way, historians have always had a close relationship to digitized materials in so far as their work depends on the open access to them. I first started using openly accessible resources before I came to the UofL when I was still at the University of Northern British Columbia in Prince George, where they had a collection of primary sources for Women’s History called the Gerritson Collection of Aletta H. Jacobs. It originally was in microfiche but was converted to a digital format, so that now all the primary source materials are available online.

I am a historian with an arts background, and my research is based on the analysis of visual images, which explains why I need primary sources for my work. In a way, historians have always had a close relationship to digitized materials in so far as their work depends on the open access to them. I first started using openly accessible resources before I came to the UofL when I was still at the University of Northern British Columbia in Prince George, where they had a collection of primary sources for Women’s History called the Gerritson Collection of Aletta H. Jacobs. It originally was in microfiche but was converted to a digital format, so that now all the primary source materials are available online.

TC: How can people access it?

We have a subscription to the Gerritson here at the University library that everyone on campus can conveniently access from their work desks with their University IDs. Considering our remote location, this multi-lingual primary source digital resource enriches the scientific practice of our scholars and students here, because the database grants easy access to a vast international collection (1543-1945) that includes magazines and newspapers from 1860-1900 and a monograph series with over 4000 digitized books and pamphlets in English, German, French, and other languages.

When I am teaching a particular topic like women’s suffrage in my History 2800 Women’s History class, for instance, I will start by looking at the Gerritson Collection to find relevant documents from international locations at the time. The articles I want my students to use, I either upload to my Moodle course or students access them directly through the library. Thus, because of our library subscription to the database we have immediate access to resources on Women’s History that are always up-to-date and growing.

TC: What other more freely accessible resources do you use for your classroom and research activities?

Most historians use Open Access (OA) materials and it came out of the desire to use primary sources in the classroom that we now all access OA materials and Open Educational Resources (OER) in our history courses. The thirst for knowledge in Women’s History has always been about retrieving data about women’s lives and circumstances to build more information and thereby enable more research in that field. Owing to the commitment of many archives to digitize their materials, more historians and more students can do their research with fewer hurdles. This primary commitment to create resources might well be the reason why, compared to other academic disciplines, historians have more openly accessible materials in their field to work with.

One of the resources I frequently use for my teaching is the Galt Museum & Archives because they have a fantastic OA collection of digital historical items that students can access conveniently from any place with an internet connection. Another oral history site for free classroom use that includes audio podcasts and video broadcasts of interviews, transcripts and photographs is the CBC Digital Archives. There is, for example, a fantastic show called THIS NATIVE LAND which was broadcasted in the 1970s and that radio broadcast dealt with very topical issues within indigenous communities across Canada. Only last week, we listened to a short piece from that in our class. I think that too few people are aware of the many scholarly resources that can be accessed through the university library. The best route to these is to consult the Library Subject guides under specific disciplines, The Women and Gender Studies library subject guide is popular and the faculty picks posts to our favourite website of OA collection.

TC: How do you navigate the wealth of information to find the materials that you need?

Owing to the topic-driven nature of my courses, I let my searches be ruled by those themes. I usually know exactly which collections to draw from because I am aware of the thematic organization of the US and Canadian resources in that field that make a topic search relatively easy. Being familiar with the field of Women’s History and the histories of photography adds to my ease in seeking photographs visual evidence.

My approach to thematic searches for teaching Women’s History is feature a single individual, who is an activist in some way and about whom I can gather all the resources that will be helpful towards building the bigger picture of her life and work. Anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells, for instance, was one of the founders of the National Association of Colored People (NAACP), a major national civil rights organization in the US. Having been a women’s historian for more than 40 years, has helped me build a compounded knowledge of the landscape around the history of this influential woman activist, which includes all the materials I have available for my teaching, such as exhibitions, books, publications and websites.

TC: How do you teach your students to work with the vast amount of openly accessible materials?

What I do is to ask the students to investigate specific resources for their utility, depth and value. I want them to look deeper and spend time to understand where a search can take them, because that is what prepares them to do research as opposed to shallow browsing. While looking at suggested OA sites, I encourage students to build their digital literacy skills and hopefully also develop an excitement for doing research themselves. The necessary parameters for the task are set when I tell the students to pick a theme to research but let everything else drop away for the purpose of the assignment. I like the idea of the students conversing over the specific digital resources in groups and to subsequently share their perspectives with their peers. My role as a teacher is to ‘open the door’ and show the students what’s there, which will hopefully instill a willingness in them to do more of their own thorough searches at a later point. They key here is to have very good browsing tools and keywords on these digital open education history sites that improve a student’s ability to navigate.

There are four databases I want to cite as examples for student investigation assignments. The first one is Click: The Ongoing Feminist Revolution, an amazing live and active website of profound complexity and sophistication that’s got an extraordinary timeline for topics like women’s bodies, political and social movement, and work and family life. Click assembles primary sources resources like biographies, documents, legal documents, photographs, speeches, and manifestos.

The second resource is the The Alberta Women’s Memory Project, a website that comes out of the University of Athabasca and collects oral history documents, memories, and memoirs. The Alberta Women’s History Memory Project links to other digital databases and sources in the province and invites people to donate materials such as original oral history transcripts or recorded oral history interviews with women throughout the Province. The site also incorporates students’ work, which means we encourage our students to read other students’ work that documents provincial Women’s History.

RISE UP: Digital archive of women’s activism website is the third example of a great online learning resource that comes out of Ontario. The site revolves around the activist histories of a very diverse women’s group including immigrant women and women of Afro-American descent. On RISE UP, students may find newsletters and publications produced by women in Canada from the 1970s to the 1990s. There are also posters, pins, and many of the ephemera of activism students can utilize for their research.

The last of the four resources students are assigned to determine its research value is Women’s Suffrage and Beyond, a website initiative by senior Canadian historian Veronica Strong Boag that comes out of UBC, which includes research essays as well as blogs. The world enfranchisement chronology I find the best and outstandingly thorough chronology of women’s suffrage worldwide.

TC: What impact does the easy and often free access to materials have on your professional practice and your students’ learning?

Originally the textbooks for Women’s History would incorporate secondary sources often paired with primary sources, but the concept of that design for textbooks have become obsolete with the broadening mandate of libraries and museums to digitize history archives. Having digital archives has made teaching much more innovative because teachers can select and adapt specific items so much more flexibly now. I, for instance, use Moodle as one of my information hubs, where I upload new finds for particular weeks, so that students can access them there. I want to provide my student with appropriate reading materials to the topic or theme of each week. When I compare available resources today, I think that textbooks are more confining or limited when it comes to showing students original evidence of women’s lives, whereas the digital sources are just wide open. I guess I hadn’t realized how fully open my practice has become fused with digital resources, but amazing technological advancements have brought digital resources to a point where I can even find 3D material objects online and no longer need to make do with print copies or travel to specific locations in order to view or handle those objects.

Adopting Open Pedagogy as a new method of teaching has really enlarged what I can do in the classroom because I can look for stories of women’s lives and circumstances far beyond our region. Digital content and technology opens up doors to the world – it’s kind of remarkable that way. In the case of teaching lynching. For instance, in the case of how Ida B. Well has worked to expose and stop lynching in America in the early 20th century, I show the original photographs (there were thousands produced and marketed) and warn the students to be fully aware of the explicit depiction of violence in them. Because the internet does not necessarily provide an informed perspective, I am obligated as an educator to tailor classroom materials to include the necessary background that will help students to look at the materials with more educated, critical eyes. The images of lynching are sensational and shocking but to see these disturbing visuals definitely demonstrate to students that lynching existed as a targeted form of violence against Afro-Americans in the post-slavery era.

TC: Is there a difference in the selection of materials that you choose to build your introductory and higher-level courses?

Not really. I use the modular approach in all of them. Although, this year for my third level courses, I reverted to using a textbook. In my third year class on I used an open textbook from the University of Athabasca Press, that is available as a low-cost full print version and a free online copy. I assigned a book from their collection which is an edited collection that was published recently. As it didn’t fulfill all the topics that I wanted to cover, I also used the University Databases and placed articles from there on to E-Reserve. In my opinion, that combination is a useful way of how we as faculty can build and broaden the text for a course. I’ve only started using E-Reserve in the last few years, after I had talked to the University Copyright Advisor Dr. Rumi Graham about it. That’s when I realized how fantastic E-Reserve is as a tool in terms of access and how it enables student access to resources. It is much more efficient than having a binder of articles, which is expensive for students, we can put a range of sources into it, starting with scholarly articles and continuing with newspaper articles, podcasts and newsletters. All of these resources can be accessed by students from home-Reserve acts putting together a personal course reader in a sense, but unlike with a bound copy I am able to self-select the content and build the course from that. The time faculty spend on the advance content assemblage pays off because you link your academic freedom with a way that saves the students some money.

TC: What do you think about students contributing to the pool of Open Educational Resources in your field?

That’s very valuable because student produced research can be incorporated on so many levels. I did, for example, have a History 2800 history student who worked on the Alberta women’s memory project website and as an emerging oral historian she was excited to see that anybody could contribute to it, which encouraged her to understand that she might potentially share an interview with a family member on that site.

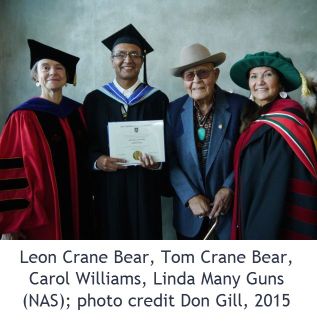

Convocation Picture

In addition, three other of my senior or graduate students – Karissa Patton, Shannon Ingram, and Leon Crane Bear – all contributed with their original research to a peer reviewed Canadian-based scholarly website called ACTIVEHISTORY.CA that publishes articles by emerging and established scholars across Canada on a broad range of topics. Patton and Ingram’s contributions filled in some of the gaps in the history of reproductive health in Southern Alberta whereas Crane Bear’s article on the Red Paper published in 1970 was an important manifesto authored by Alberta’s Association of Indian Chiefs. ACTIVEHISTORY.CA acts like a textbook and a blog at the same time. It’s scholarly in all regards: it has a consistent editorial policy, and essays include footnotes and hyperlinked quotations, which lead the reader to all the relevant sources. If somebody quotes a piece of legislation, for instance, the article is linked to that legislation. If somebody cites a historical archive, it’s linked to that archive. They’ve done an excellent job at producing what we would see as a textbook, but the weekly additions keep the discussion more current and authentic than a textbook could ever be. So ActiveHistory.ca has emerged as a new form of a textbook, which for me as a historian is a great research tool and it’s great for the students too because they can contribute to it with peer-reviewed publications that go online immediately after their acceptance.

Last but not least, I also use my students’ work in the classroom now, which is fantastic. In the Winter (2016) and Spring (2017) terms, for instance, I invited Karissa Patton, who used to be an Honour’s and Master’s student here and is now at the U of Saskatchwan doing her PhD to do a virtual discussion with my students. To prepare for the Q&Q, I asked students to read one of her articles on the ActiveHistory.ca website and then we skyped Karissa to give the students the opportunity to ask her questions based on what they have understood from original published research.

TC: You mentioned that openly accessible materials have shaped the way you build your courses? Have they impacted other aspects of your teaching too?

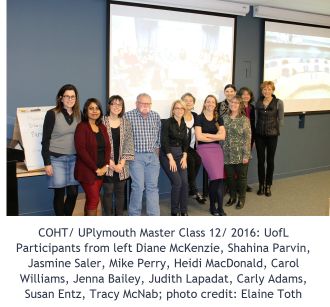

Yes, they certainly have broadened the range of methods I am using for my teaching. Now I also include the ‘Open Classroom’ approaches mentioned earlier. I consider the transporting of our students into the room with a living author as another mode of delivering Open Education. We’ve done this at the Centre of Oral History and Tradition (COHT), a research hub here on campus, as well when we recently hosted a two hour long transnational Masterclass-Collaboration between scholars and students at the University of Plymouth with our own graduate students to discuss scholarly ideas across the Atlantic.

We’ve been trying to practice Open Pedagogy in the form of Open Classrooms because we see Open Education to go well beyond just a new way of utilizing text based materials to be more engaged with the educational exchange between students and researchers. At COHT we started these national and international bilateral exchanges as experiments, which as we know now can be the base for a research hub. We hope to build relationships with other oral history scholars situated elsewhere to generate more of those inspiring conversations. The prospect of talking to an author is what stimulates our students to prepare thoroughly for the professional exchange of knowledge and ideas in our field. These head-to-head conversations are where I’ve stepped up a little bit around OER in the last two years, so that now I hope to bring students into contact with authors in ways they can engage in national and international conversations through digital means. Being part of that, students begin to become aware of the global strands of discourse, which really helps us in the classroom to allow educators to gain greater credibility.

TC: Where would you recommend an interested instructor with less OER exposure to begin?

There are many scholarly materials out there online that can be useful. You might start from your textbook if you assign one and you think it’d be great to have one of the authors from that book in your classroom. The only thing needed is a youtube search with that name, which usually prompts a TEDx talk or an interview with that person. That’s a good start for someone new to utilizing scholarly resources online. The next step might be to revise one’s understanding of what academic publications are. People are so used to believing that conventional publications need to be hard copies, but in my view that understanding is outdated. As I have said earlier in this interview, Open Educational Resources are in no regard any less valuable. On the contrary, with rigid peer-editing processes in place they are generally as good in quality or better, especially in regards to a broader audience, authenticity, affordability and topical relevancy.

I am currently writing an article which will be published on an Open Access site and do, of course, wonder whether I might have been less eager to spend so much time to publish it openly at an earlier stage in my career. The advantage I see today to publishing on Open Access sites is the more unusual and diverse readership that gets exposed to your work when your name or materials pop up on Google, which might also result in a greater international attention. The immediacy of access and low cost to my students are two more convincing arguments that might speak to the reluctant. A simple example to illustrate why I argue for Open Access is the fact that I am going to Norway this summer as a researcher because some Sami researchers found my work online. I don’t think that those people would otherwise have known about me had they not accessed my profile and my publications online. That’s how Open Access and OER can lead to an exchange of Sami researchers working with indigenous photography in Norway with me as a Women’s Historian based in Lethbridge. In other words, I am certain that Open Education is a key to international academic conversations that can lead to the mobilization and exchange of knowledge in your field.