CHAPTER 5 – DEVELOPMENTAL AGES AND STAGES

|

Learning Objective Identify the unique developmental ages and stages of young children and the practices that best meet the developmental needs. |

NAEYC STANDARDS

The following NAEYC Standard for Early Childhood Professional Preparation addressed in this chapter:

Standard 7: Promoting Child Development and Learning

Standard 8: Building Family and Community Relationships

Standard 9: Observing, Documenting, and Assessing to Support Young Children and Families

Standard 10: Using Developmentally Effective Approaches to Connect with Children and Families

Standard 11: Using Content Knowledge to Build Meaningful Curriculum

Standard 12: Becoming a professional

PENNSYLVANIA EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATOR COMPETENCIES

Child Growth and Development

Families, Schools and Community Collaboration and Partnerships

Curriculum and Learning Experiences

Assessment

Professionalism and Leadership

Communication

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE EDUCATION OF YOUNG CHILDREN (NAEYC) CODE OF ETHICAL CONDUCT (MAY 2011)

The following elements of the code are touched upon in this chapter:

Section I: Ethical Responsibilities to Children

Ideals: 1.1 – 1.4, 1.10, 1.11

Principles 1.1, 1.2, 1.7

Section II: Ethical Responsibilities to Families

Ideals: 2.2, 2.4, 2.6, 2.7

Principles: 2.6

Quotable:

“Babies are such a nice way to start people.” – Don Herald

PREVIEW

This chapter examines the child as a whole or what we commonly refer to in Early Childhood Education – “the whole child.” The whole child refers to and addresses all areas or domains of the child – physical, cognitive, language, social-emotional, and spiritual. These domains of development are both collective and individual. Children have similar characteristics at different developmental ages, but they also are individuals with their own – “me-ness” that is important for us to consider when supporting all children in our early learning programs.

THE WHOLE CHILD – DEVELOPMENTAL DOMAINS/AREAS

|

Pause to Reflect When you think about young children, what images emerge for you? How do you see them? What are some words that you may use to identify them? |

When thinking about children, what comes to your mind? Is it the way they engage with you? Is it their sense of adventure? Is it watching them try to climb a ladder? Is it trying to figure out what they may be thinking about when they have a certain look on their faces that they are not yet able to articulate? Is it their obvious curiosity and imagination? This is how we begin to think of the child as a whole, complex being. An integrated, interrelated series of parts that become the “whole.”

Figure 5.1 – Does an image like this come to mind when you think of children?xlix

In the field of Early Childhood Education, we identify these areas of development as domains. These domains (areas) are as follows:

Physical Development

Physical or physical motor development includes large or gross motor development, fine motor development, and perceptual-motor development. The large or gross motor development of children consists of their large motor groups – running, jumping, skipping, swinging with their arms – in other words, the muscle groups that are closer to the body. The fine motor development of children consists of the small motor groups, like writing with their hands, and squishing sand in-between their toes – muscle groups that are further away from the body. The last area of physical development is the perceptual-motor – the ability to catch a ball, to use a paintbrush, and paint to create something from their memory – in other words, it refers to a child’s developing ability to interact with their environment by combining the use of the senses and motor skills.

The first few years of life are dedicated to the heightened development of these skills. In the first year of life, they go from barely being able to hold their head up to walking upright. As many of you taking this course have varied experiences with children, this may be a refresher, but for some of you, this may be new information. It is crucial to the development of children, that they have many opportunities to use their bodies as their body is developing new pathways for success. In an early learning environment serving children from 0 – 5, there should be ample space and materials for children to explore and practice their emerging physical skills. This includes allowing them to take risks with their bodies allowing them to explore possibilities. These risks afford children opportunities to feel that they are capable as well as gives them a sense of agency.

Figure 5.2 – What physical motor skills is this child practicing?l

Cognitive-Language Development

Cognitive or brain development speaks to how we process information, our curiosity/imagination, long and short-term memory, problem-solving, critical thinking, language both receptive and expressive, beginning reading, computing skills, creativity, etc. In other words, how our brain develops helps us to think about and understand the world around us.

We often place much emphasis on this area of development to the detriment of the other areas of development. They all work in concert. When thinking about developing the “whole child” we need to be mindful of providing experiences that promote all of their development, not just their cognitive development.

As with the other areas/domains of development, the first 5 years of life are important in establishing the foundation for learning. This includes providing lots of rich experiences for exploration, curiosity, imagination, use of materials and equipment (that also fosters physical development), opportunities for talking (even with pre-verbal babies), etc. The learning experiences that we provide for children will be discussed in Chapter 6 – Curriculum and Chapter 7 – Learning Environments. Both of those chapters are dedicated to looking at the learning experiences (curriculum) and the environments we set up to support children’s whole development.

Social-Emotional Development

Social-emotional development is the relationships that children have with themselves and others, the way they feel about themselves or their self-concept, the way they value themselves or their self-esteem, and the ability to express their feelings to themselves and others.

One of the important dispositions of being an early childhood professional is supporting children’s well-being. It is both a moral and ethical responsibility. By nature, children are trusting and look to the adults in their world to provide them with the necessary skills to be successful in their life’s journey. We can either elevate or diminish a child.

Figure 5.3 – What relationship do you think these two children have?li

Spiritual Development

Spiritual development, or considering the “spirit” of the child, is something that is a more recent addition to thinking about “whole child” development. In a recent article entitled Supporting Spiritual Development in the Early Childhood Classroom by Amelia Richardson Dress, she cites emerging research that indicates the importance of considering this element of a child. “Spirit is the thing that makes us us. Spirituality is the way we connect our ‘inner us’ to everything else, including other people’s inner ‘us-ness.” lii Our spiritual development is a part of our social-emotional development; however, we find it important to call this out specifically to guide our practice of supporting and elevating children’s uniqueness. Chapter 6: Curriculum, looks at how to support children’s curiosity. A curriculum that is based on children’s interests, engages their curiosity, is playful, and provides trust, elevates how children see themselves as dynamic, competent human beings. Simply by providing rich, open-ended materials and encouraging their natural desire to ask questions, we support a child’s sense of wonder.

DEVELOPMENTAL AGES AND STAGES

|

Pause to Reflect What do you know about the various ages and stages of child development? What interests you in working with children? Do you have a particular age group that brings you more joy? What do you know about that age group?

|

Identification of the common characteristics of children at various developmental ages has been around for quite some time. Gesell (mentioned in Chapter 2 – Theories of Early Childhood Education) and Ilg conducted research to identify some of these common characteristics of each developmental age. They published a series of books that provide a comprehensive look at those developmental ages. Parents, as well as early childhood professionals, have found these helpful to understand how to relate to and interact with children as we socialize and educate them in our homes and our schools

Other theories have used these to define how to interact with children, what to expect from children, and how a child’s brain develops (Refer back to Chapter 2 Theories of Early Childhood Education). For early childhood professionals, theories help us to set up our curriculum, our environments, and our expectations, and build meaningful and engaging relationships with children to support the “whole child.”

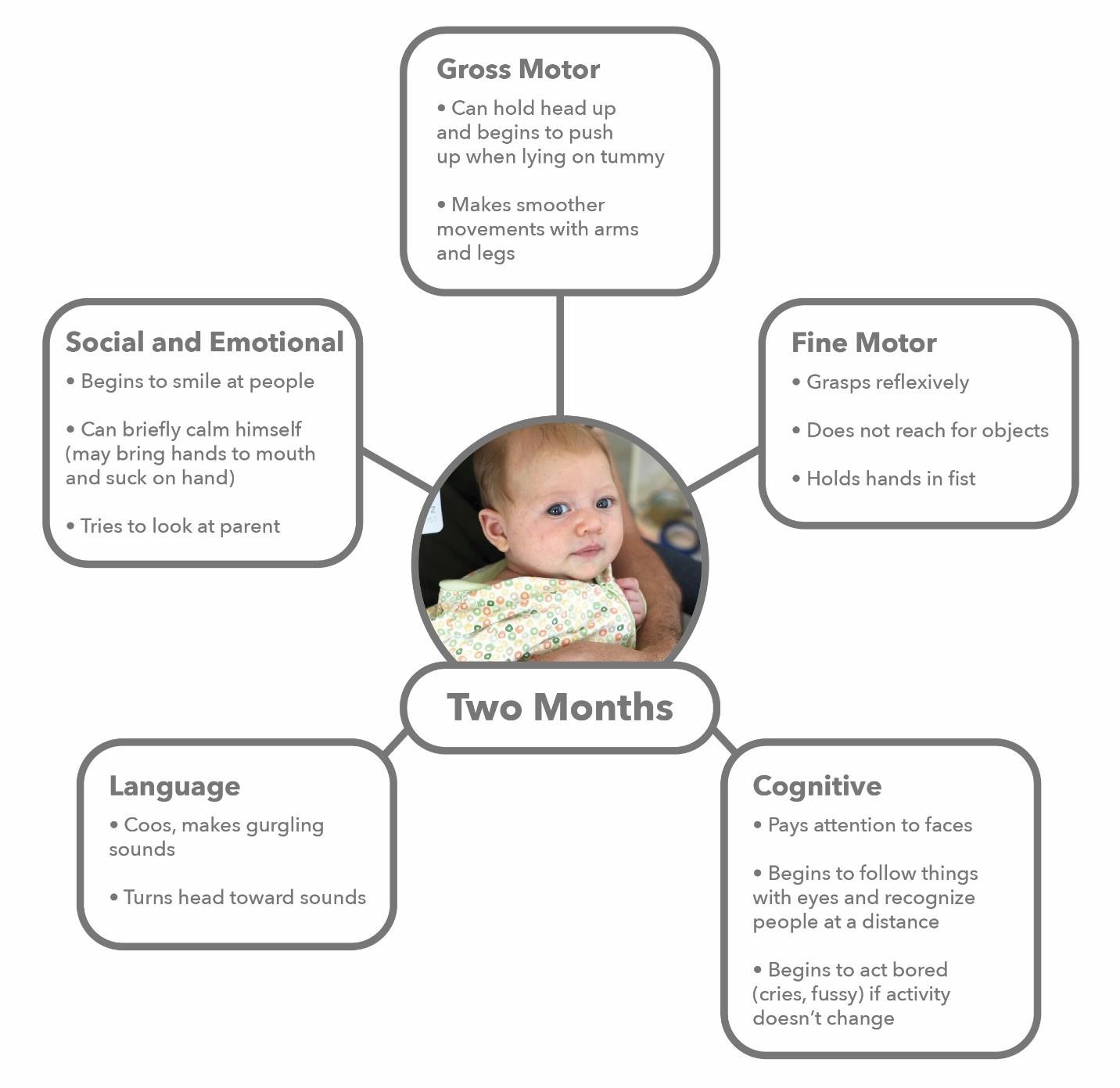

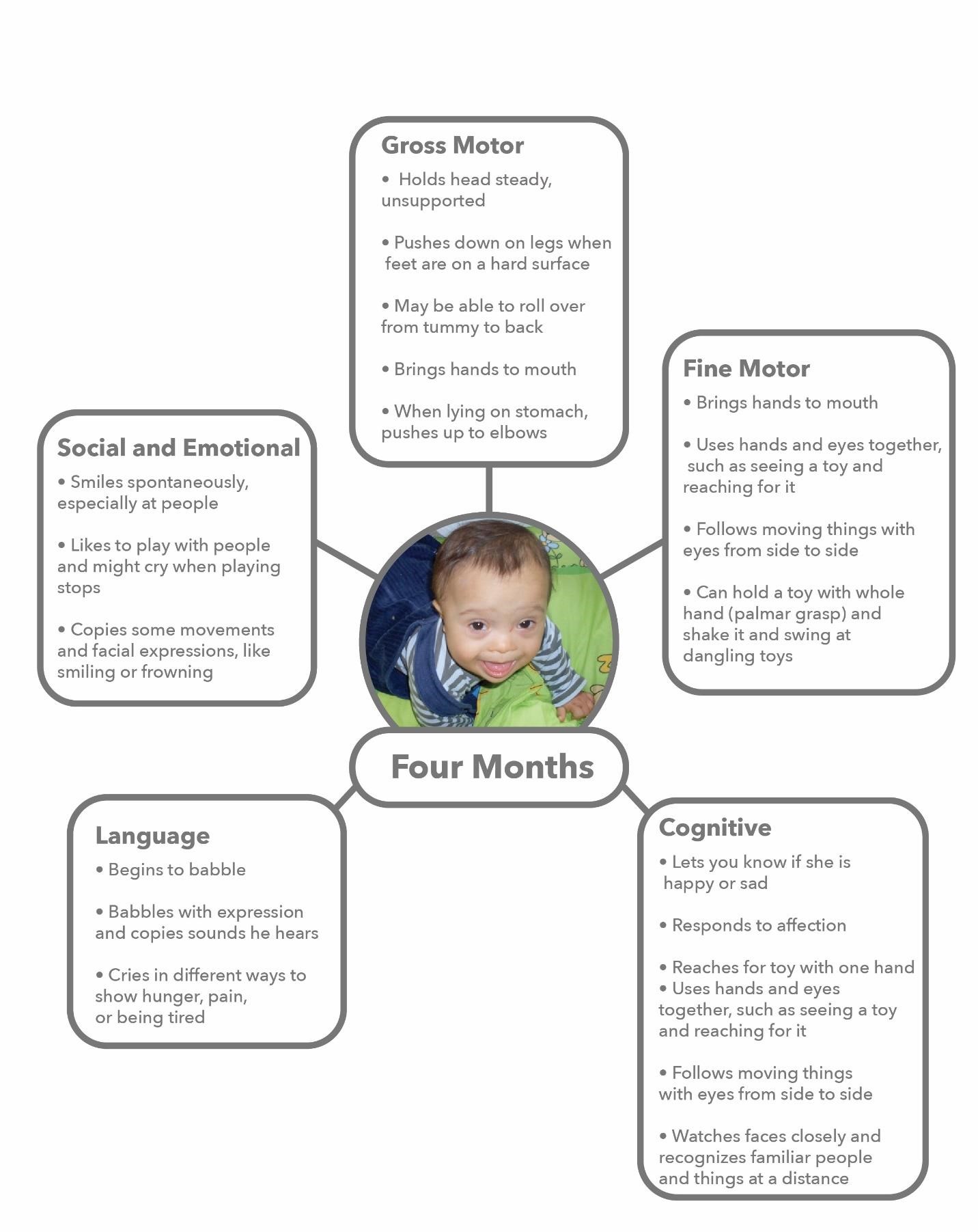

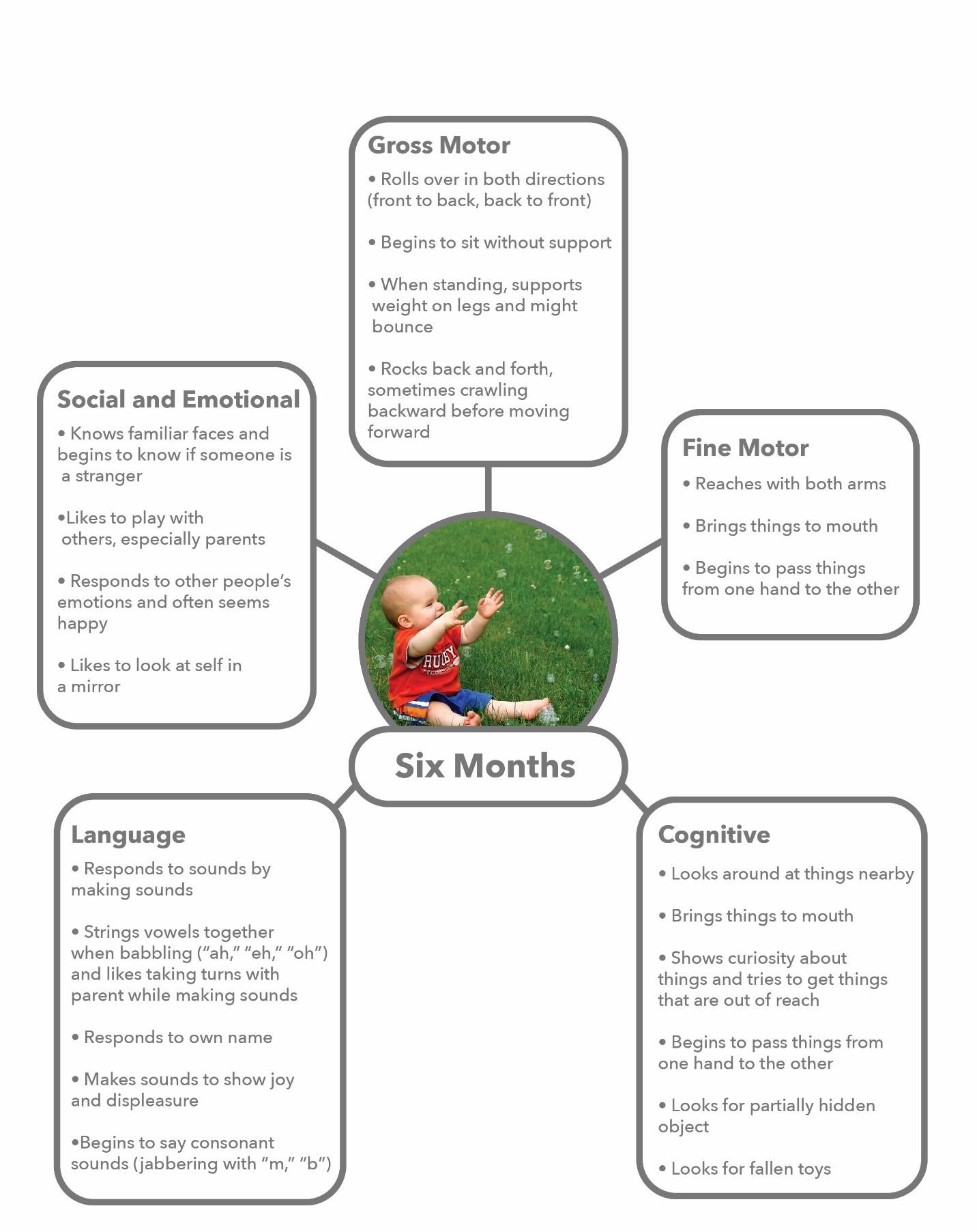

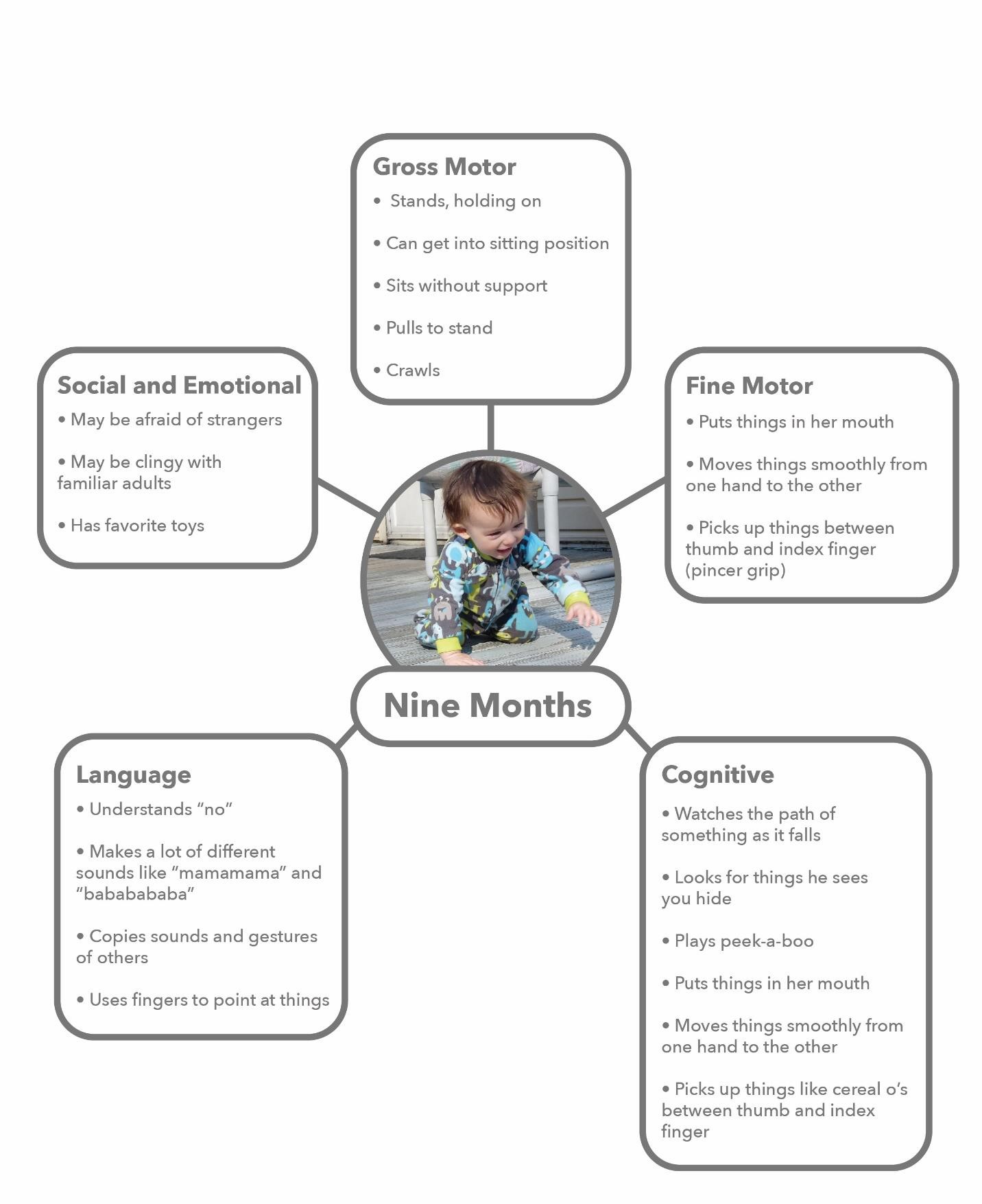

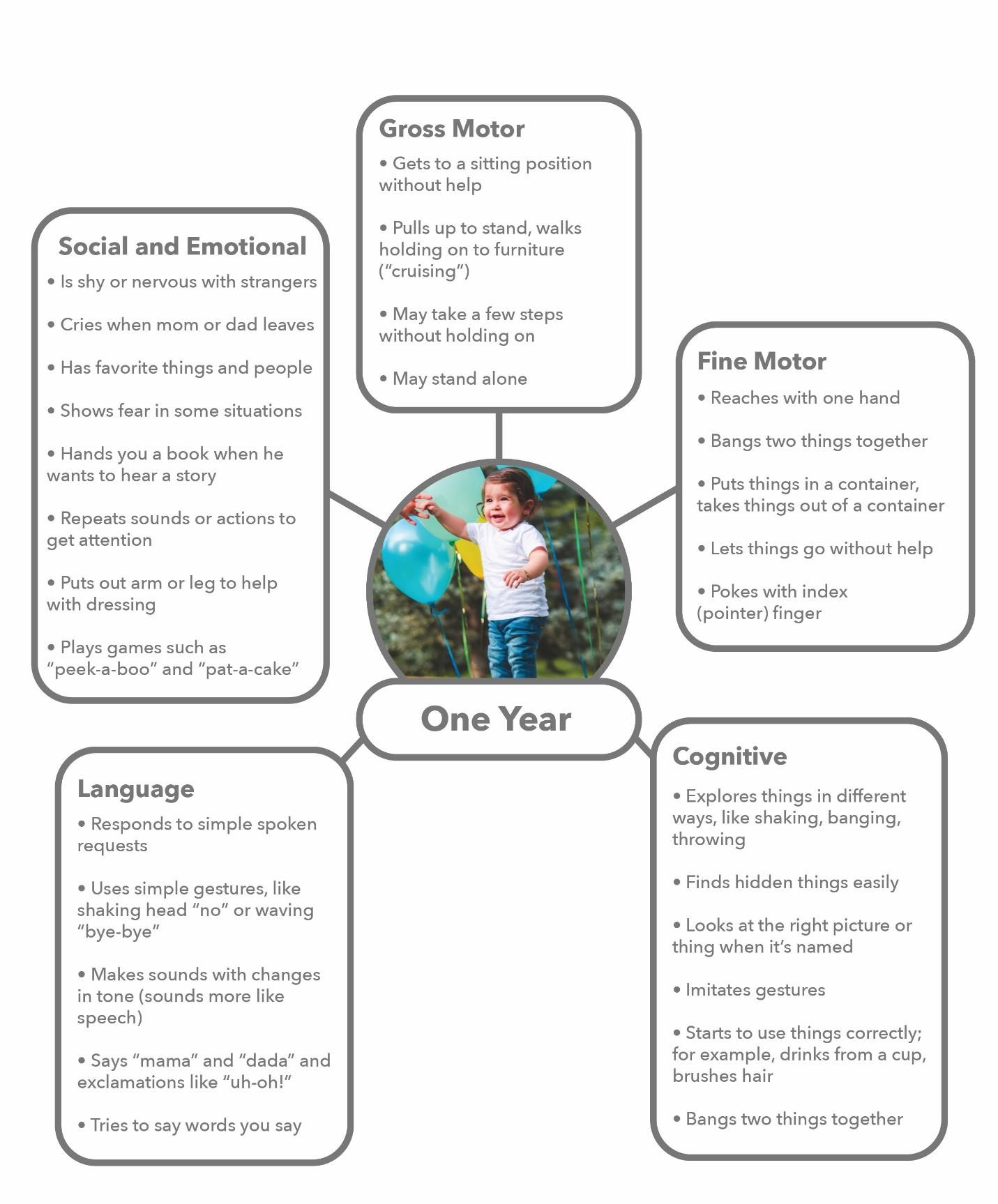

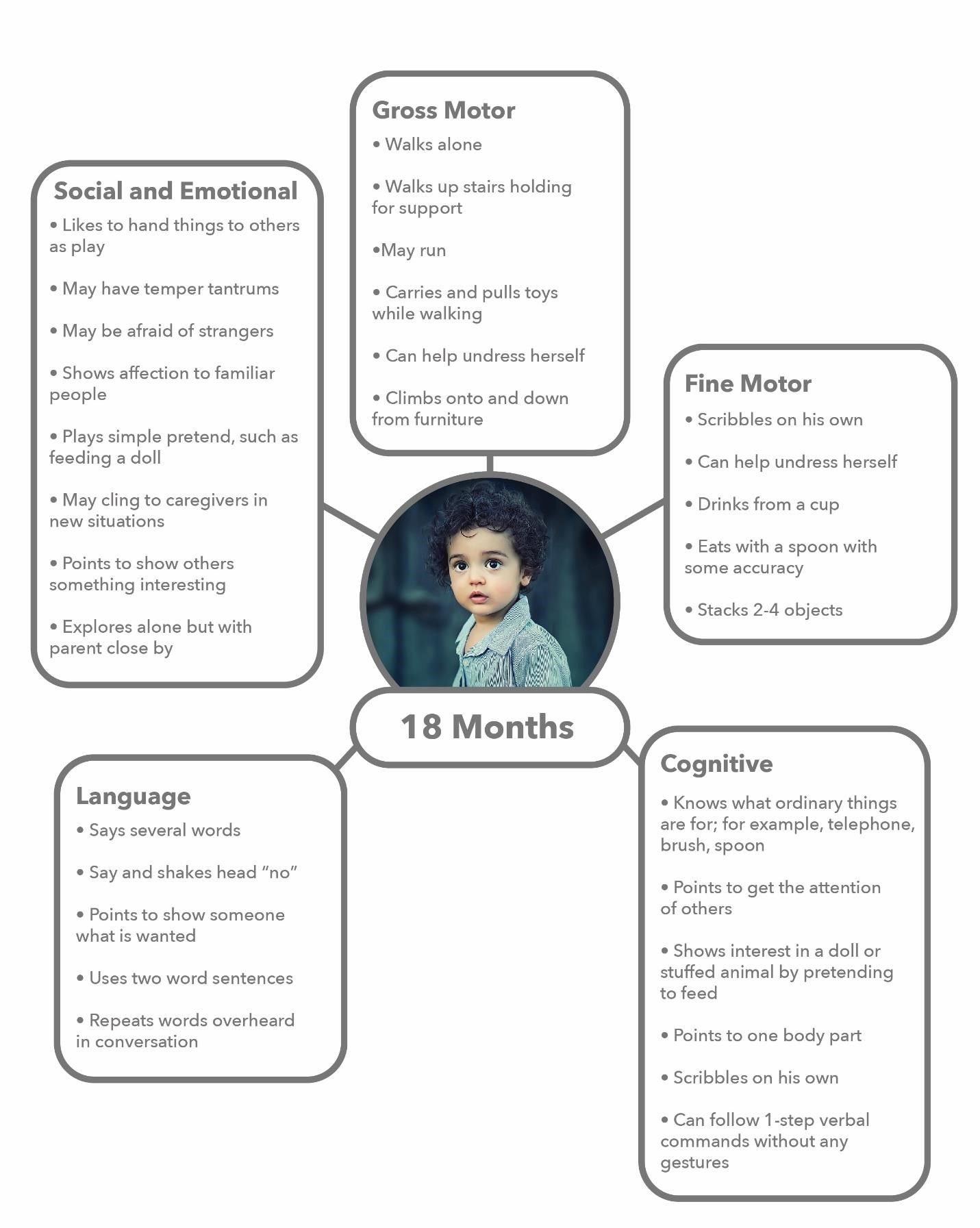

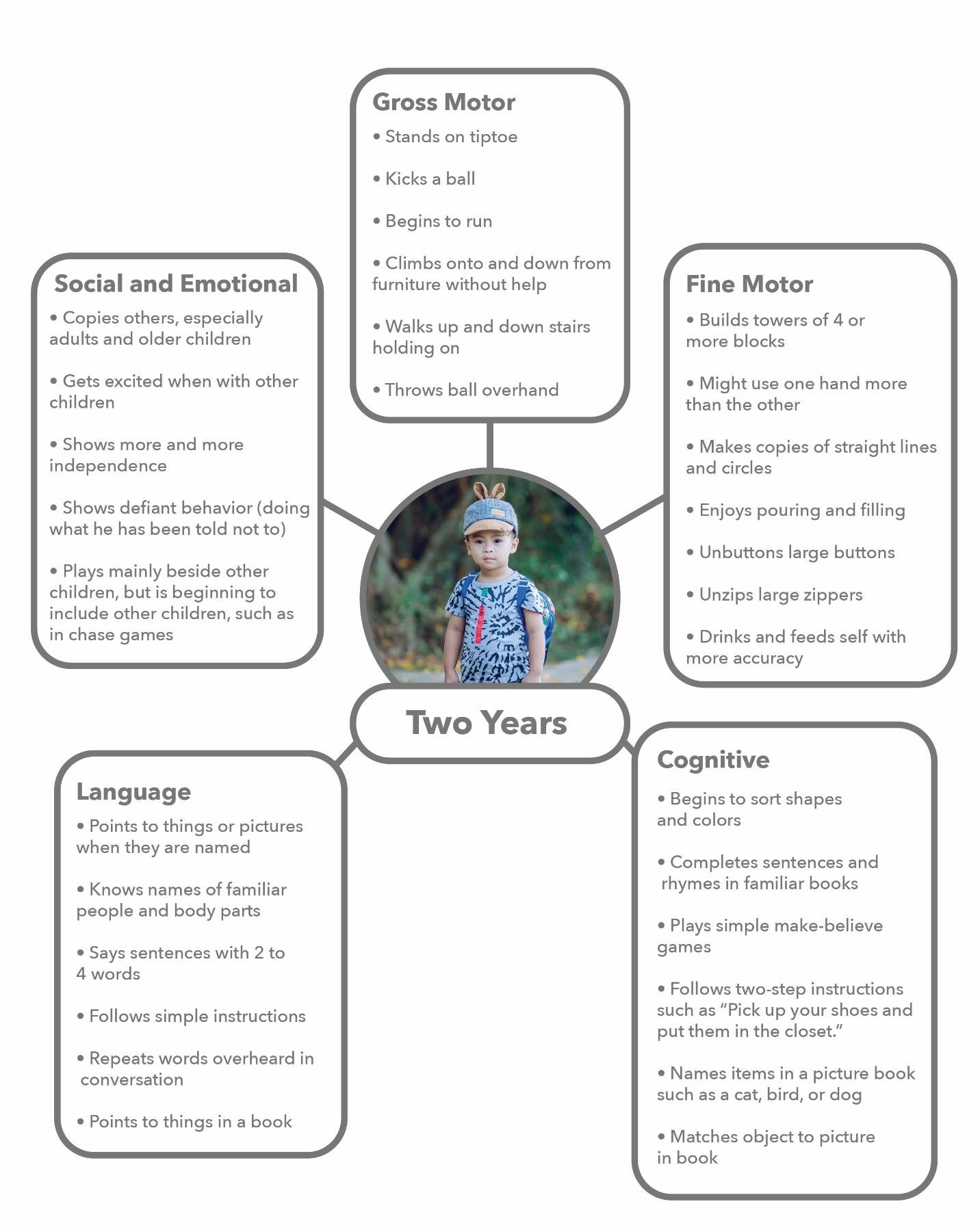

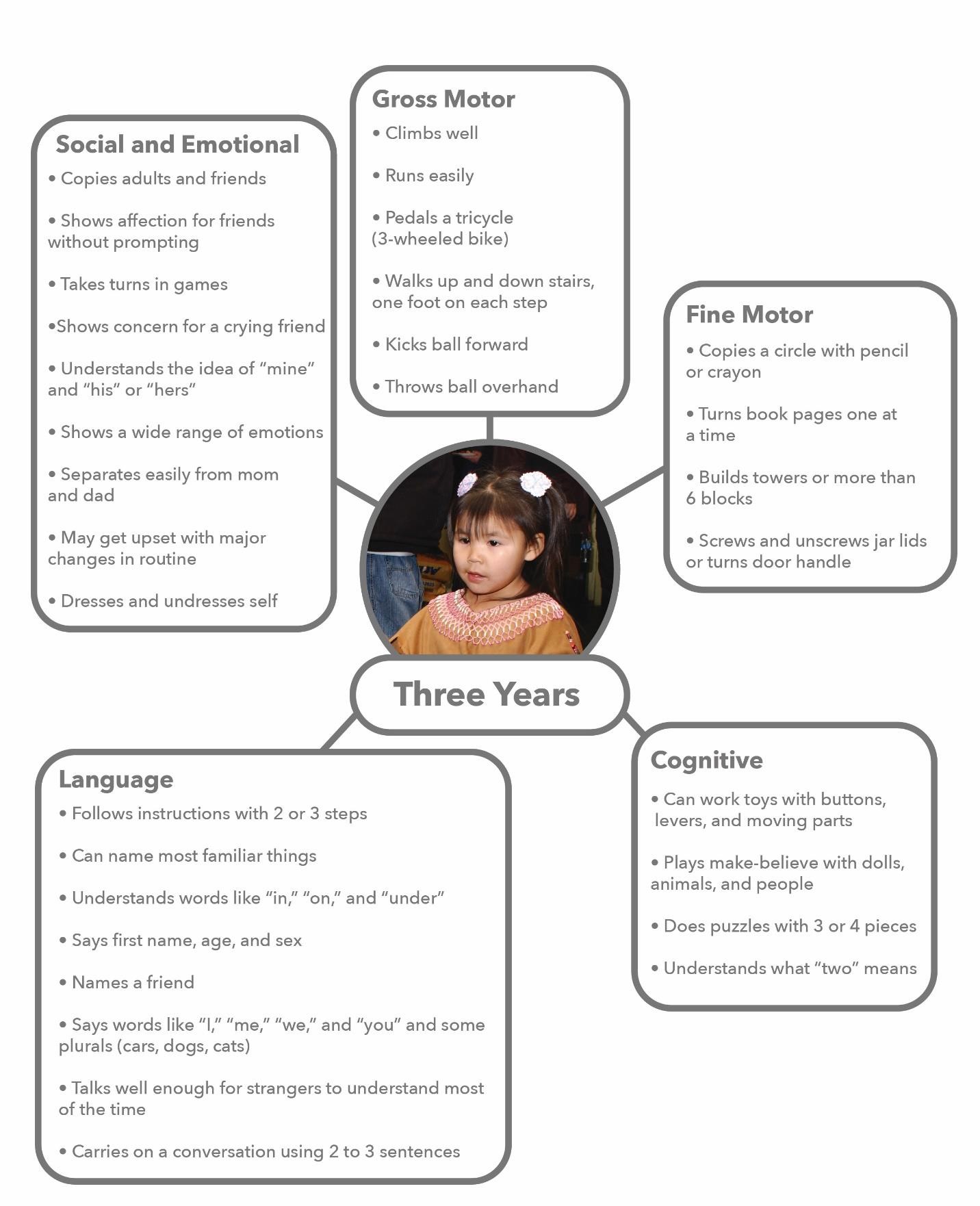

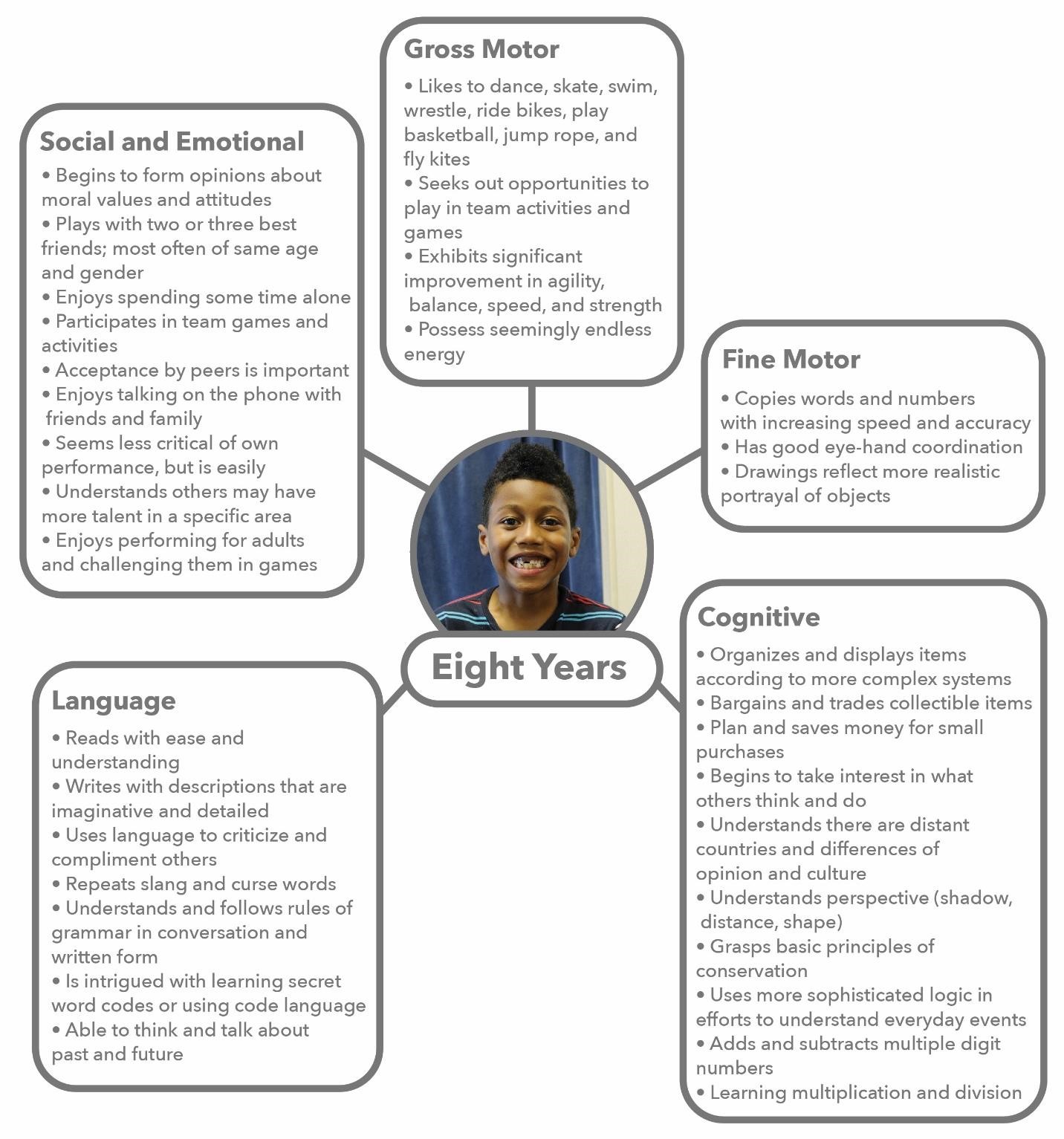

The following graphics provide an overview of these developmental ages and stages (aka milestones). It is important to note that using these age-level charts requires discretion. While they help to define “typical” development, children also are unique in their developmental progress. We use them as guidelines to help inform our practice with young children.

We must always remember:

The milestones to gain a deeper understanding of the age group as a whole

That each child, within that developmental age group, is a unique individual

That children exhibit a range of developmental norms over time

To resist the tendency to categorize or stereotype children

To observe each child and assess where they are developmentally

That each child goes through most of the stages describes, but how they do is the individual nature of who they are

To focus on what children can do, build on their strengths, and find ways to support areas that need to be more developed

That these milestones refer to typically developing children and are not meant in any way to represent a picture of any “one” child.

Note: You may notice that the following charts do not mention spiritual development as one of the domains. There is no specific age nor specific expectations of a child’s spiritual development. This development is ongoing as it is supported by the interactions the child has with the world around them.

Figure 5.4 – Developmental milestones typically met around 2 months of age.liii

Figure 5.5 – Developmental milestones typically met around 4 months of age.liv

Figure 5.6 – Developmental milestones typically met around 6 months of age.lv

Figure 5.7 – Developmental milestones typically met around 9 months of age.lvi

Figure 5.8 – Developmental milestones typically met around 1 year of age.lvii

Figure 5.9 – Developmental milestones typically met around 18 months of age.lviii

Figure 5.10 – Developmental milestones typically met around 2 years of age.lix

Figure 5.11 – Developmental milestones typically met around 3 years of age.lx

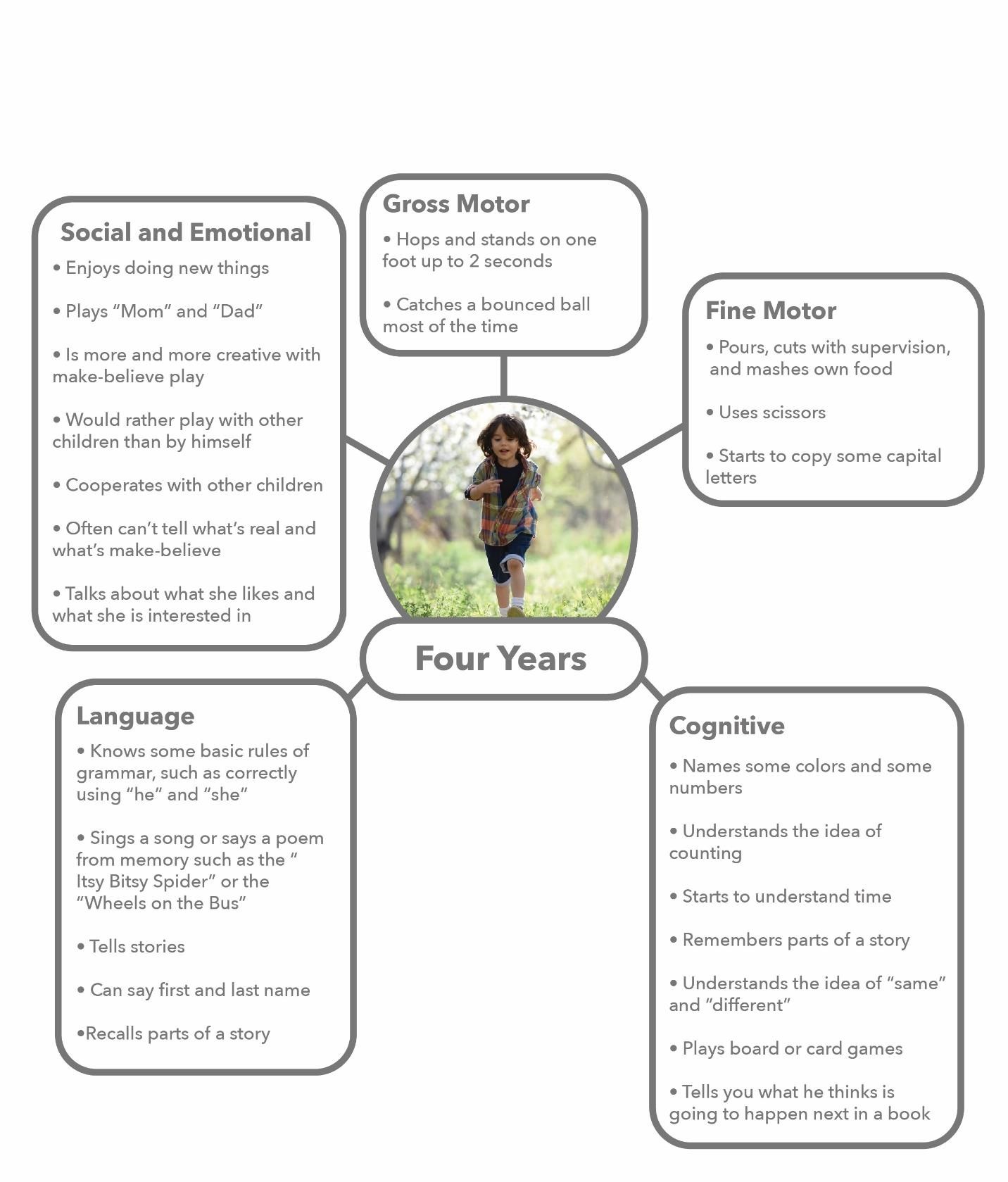

Figure 5.12 – Developmental milestones typically met around 4 years of age.lxi

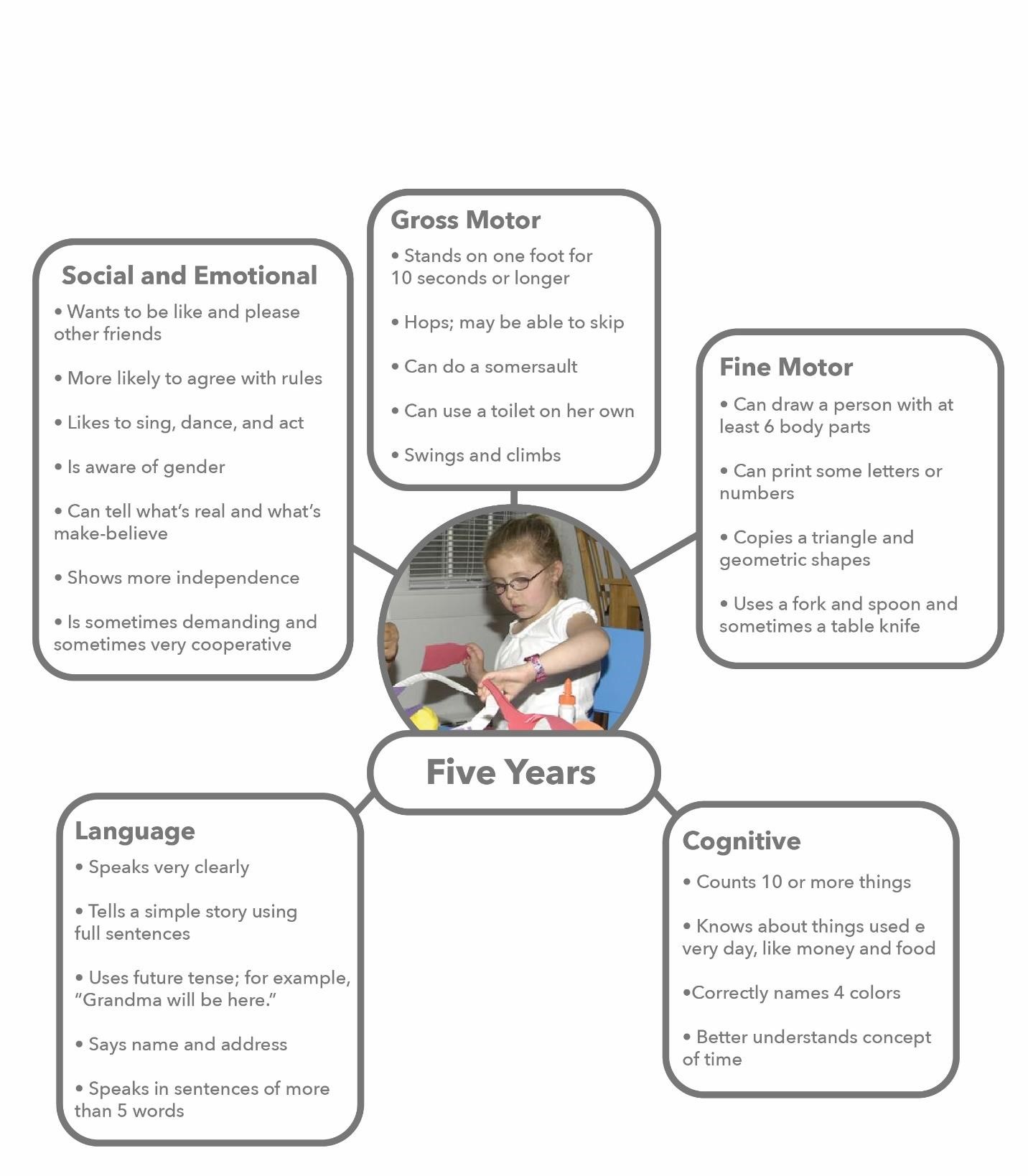

Figure 5.13 – Developmental milestones typically met around 5 years of age.lxii

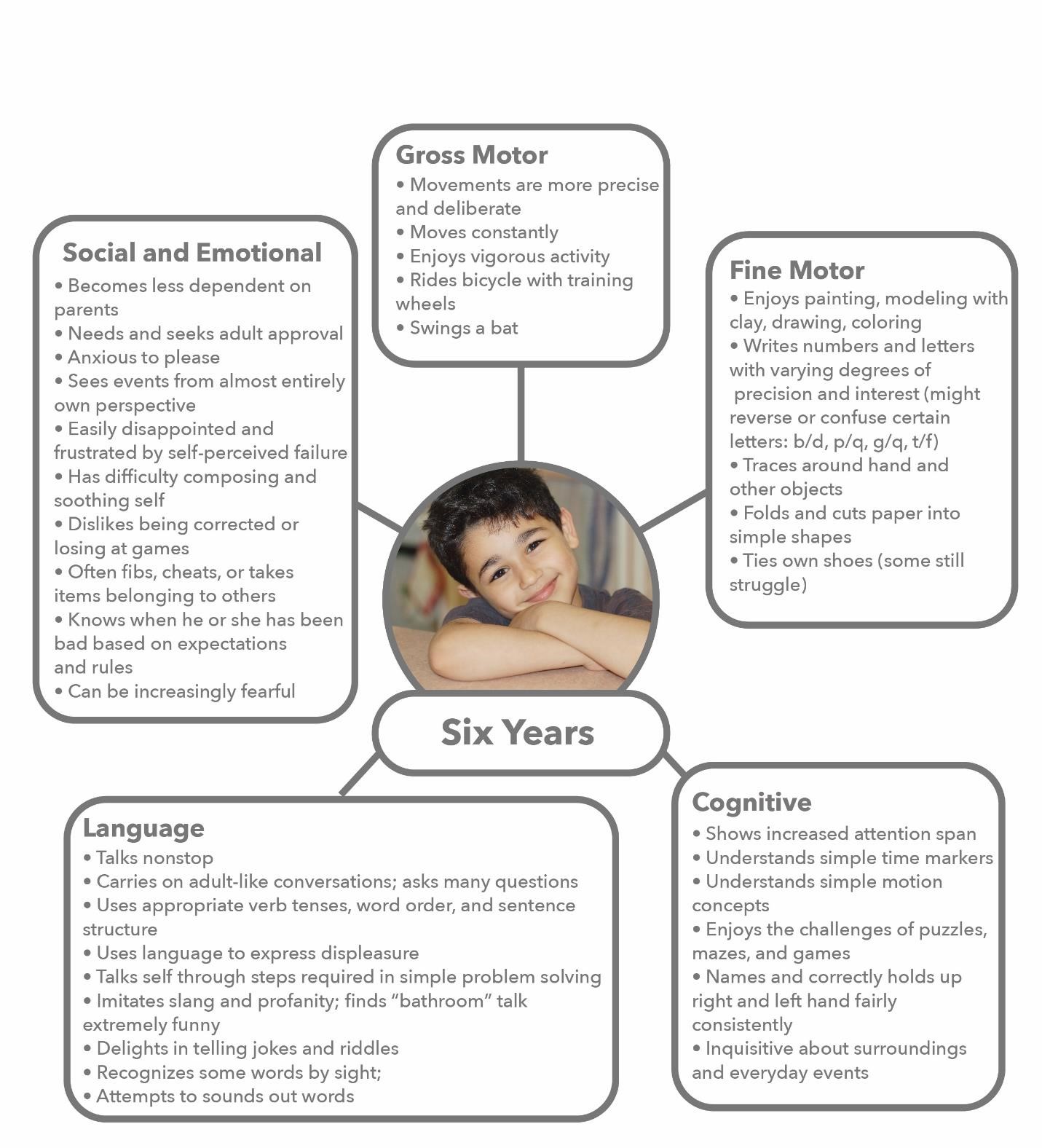

Figure 5.14– Developmental milestones typically met around 6 years of age.lxiii

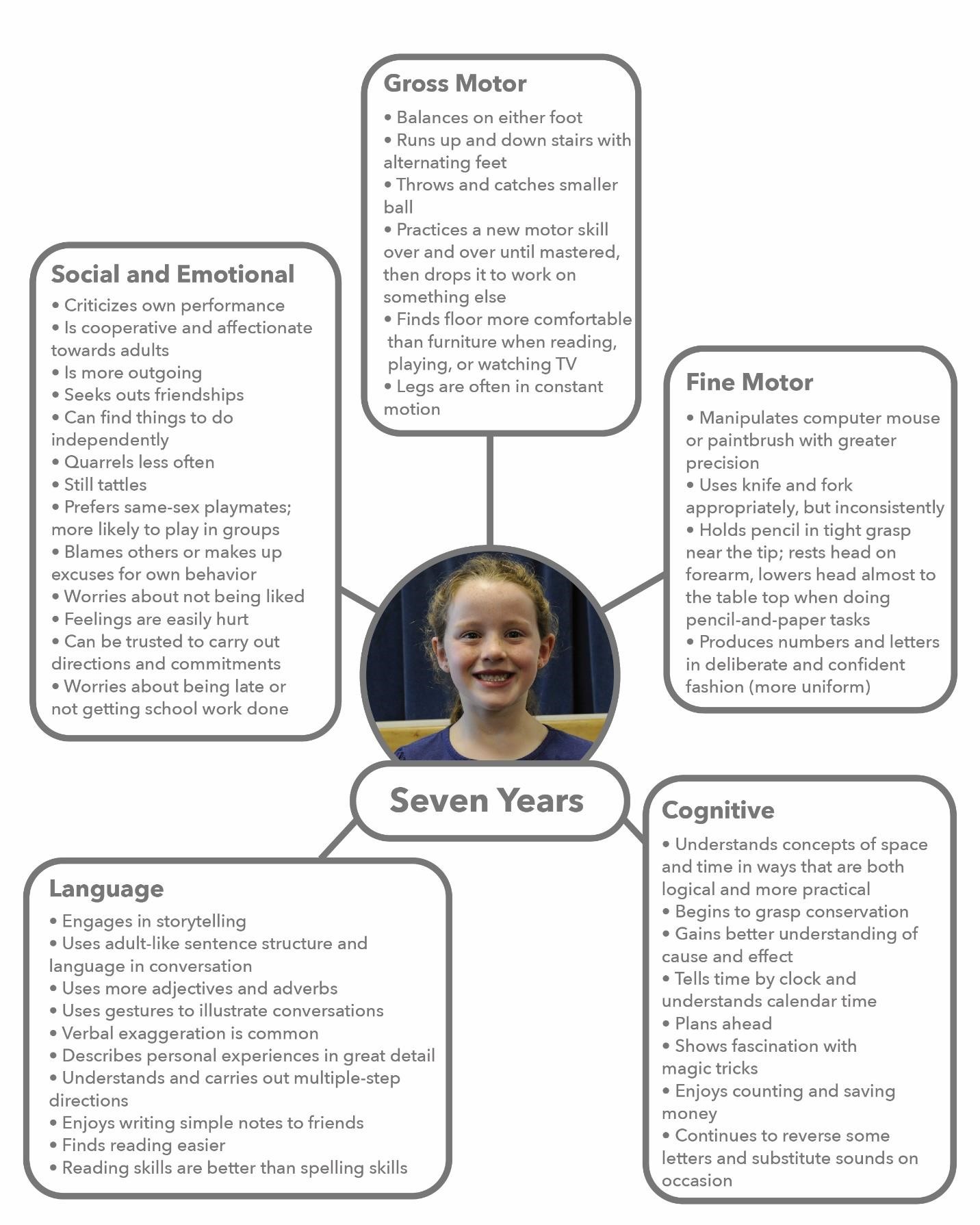

Figure 5.15 – Developmental milestones typically met around 7 years of age.lxiv

Figure 5.16 – Developmental milestones typically met around 8 years of age.lxv

|

Pause to Reflect Has reading over the developmental milestones of different developmental ages changed your ideas about children? What age group may you be most interested in working with? What age group may present more challenges for you? |

Developmental Factors by Age

Here is an additional chart to provide more context. While each child develops at their own rate and in their own time and may not match every listed item, here are some general descriptions of children by age:

Table 5.1 – Factors Influencing Behaviors by Agelxvi

|

Age |

|

General Descriptors |

|

1-2 Years |

• • • |

Like to explore their environment Like to open and take things apart Like to dump things over |

|

|

• |

Can play alone for short periods of time |

|

|

• |

Still in the oral stage, may use biting, or hitting to express their feelings or ideas |

|

2-3 Years |

• • • • • |

Need to run, climb, push and pull Are not capable of sharing, waiting, or taking turns Want to do things on their own Work well with routine Like following adults around |

|

|

• |

Prolong bedtime |

|

|

• |

Say “no” |

|

|

• |

Understand more than he/she can say |

|

3-4 Years |

• • • • • |

Like to run, jump, climb May grow out of naps Want approval from adults Want to be included “me too” Are curious about everything |

|

|

• |

May have new fears and anxieties |

|

|

• |

Have little patience, but can wait their turn |

|

|

• |

Can take some responsibility |

|

|

• |

Can clean up after themselves |

|

4-5 Years |

• • • • |

Are very active Start things but don’t necessarily finish them Are bossy and boastful Tell stories, exaggerate |

|

|

• |

Use “toilet” words in a “silly” way |

|

|

• |

Have active imaginations |

|

5-6 Years |

• • • |

Want everything to be fair Able to understand responsibility Able to solve problems on their own |

|

|

• |

Try to negotiate |

|

Quotable “I remember one morning when I discovered a cocoon in the bark of a tree, just as the butterfly was making a hole in its case and preparing to come out. I waited a while, but it was too long appearing and I was impatient. I bent over it and breathed on it to warm it. I warmed it as quickly as I could and the miracle began to happen before my eyes, faster than life. The case opened, the butterfly started slowly crawling out and I shall never forget my horror when I saw how its wings were folded back and crumpled; the wretched butterfly tried with its whole trembling body to unfold them. Bending over it, I tried to help it with my breath. In vain. It needed to be hatched out patiently and the unfolding of the wings should be a gradual process in the sun. Now it was too late. My breath had forced the butterfly to appear, all crumpled, before its time. It struggled desperately and, a few seconds later, died in the palm of my hand. That little body is, I do believe, the greatest weight I have on my conscience. For I realize today that it is a mortal sin to violate the great laws of nature. We should not hurry, we should not be impatient, but we should confidently obey the eternal rhythm.” -Nikos Kazantzakis, from Zorba the Greek |

Pause to Reflect How does this quote apply to children’s development? How can you as an early childhood professional honor a child’s current stage of development and not try to hurry them through? How can you respect each stage as an important milestone needed to experience fully in order to move successfully to the next, gradually when that child is ready? What happens when we try to hurry to introduce concepts to children they are not yet ready for? |

CULTURAL IDENTITY DEVELOPMENT

Culture can be defined as ideas, knowledge, behaviors, beliefs, art, values, morals, law, customs, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by particular people or society, and these are passed along from one generation to the next by the way of communication. Our cultural identity is an integrated part of our development.

Cultural identity refers to a person’s sense of belonging to a particular culture or group. This process involves learning about and accepting the traditions, heritage, language, religion, ancestry, aesthetics, thinking patterns, and social structures of a culture.

Early Childhood Professionals support the cultural identity of the children and families we serve. We do this by getting to know the child and their family. We stay away from our biases/assumptions about what we think we know about a particular race/ethnicity/religion, etc. and we seek to engage in relationships with families that honor how that family identifies their cultural identity.

DEVELOPMENTALLY APPROPRIATE PRACTICES

In Chapter 2 – Developmental and Learning Theories, there is a section on Developmentally Appropriate Practices. What is important to note here is that identifying the developmental ages and stages of children helps us to plan curriculum (Chapter 6) and learning environments (Chapter 7) that are appropriate for their developmental age and stage. Below is a refresher from Chapter 2 as it is pertinent in this chapter. Understanding the importance of DAP sets the stage for identifying ways in which to support children in the early childhood learning environment.

There are three important aspects of Developmentally Appropriate Practices (DAP):

What is known about child development and learning – refers to knowledge of age-related characteristics that permits general predictions about what experiences are likely to best promote children’s learning and development.

What is known about each child as an individual – referring to what practitioners learn about each child that has implications for how best to adapt and be responsive to that individual variation.

What is known about the social and cultural contexts in which children live – referring to the values, expectations, and behavioral and linguistic conventions that shape children’s lives at home and in their communities that practitioners must strive to understand in order to ensure that learning experiences in the program or school are meaningful, relevant, and respectful for each child and family. lxvii

BEHAVIORAL CONSIDERATIONS

Guiding the behavior of children is another important role that early childhood professionals possess. There are a plethora of programs designed to provide parents and early childhood professionals with the skills and tools that effectively help children navigate their emotions and the behaviors that they may exhibit at different developmental ages. Chapter 6 (Curriculum) has more extensive information on this topic. Below is a chart that provides some ideas about how to approach guidance positively.

Table 5.2 – Positive Approaches for Developmental Factorslxviii

|

Ages/Stages |

Developmental Factors |

Examples of a Positive Approach to developmental factors to manage behavior |

|

Infant/Toddler |

Children this age: Actively explore environments Like to take things apart Have limited verbal ability, so biting or hitting to express feelings is common Like to dump things over |

Children in this stage tend to dump and run, so plan games to enhance this behavior in a positive way. Have large wide-mouth bins for children to practice “dumping items” into and out of. This strategy redirects the behavior of creating a mess into a structured activity to match the development. |

|

Older Toddlers |

Children this age: Need to run, climb, push and pull Are incapable of sharing; waiting or taking turns Express beginning independence Work well with routines Say “no” often Comprehend more than they can verbally express |

Teachers of this age often find children trying to climb up on tables, chairs, and shelves. Incorporate developmentally climbing equipment and create obstacle courses to redirect activity into positive behaviors. Avoid using the word “no” and create expressions that teach what to do instead of what not to do. |

|

Young Preschool (3-4 years) |

Children this age: Like to be active Are curious and ask many questions Express new fears and anxieties Have little patience Can clean up after themselves Can take some responsibility Seek adult approval |

Young preschoolers become curious and create many misconceptions as they create new schemas for understanding concepts. Listen to ideas sensitively address them quickly and honestly. Model exploration and engagement in new activities (especially ones they may be fearful of engaging in) |

|

Older Preschool (4-5 years) |

Children this age: Are highly active Can be “bossy” Have an active imagination Exaggerate stories Often use “toilet words” in silly ways Start things but don’t always finish |

Ask the children to create new silly, but appropriate words to represent emotions rather than focusing on the “bad” words they use. |

|

Ages/Stages |

Developmental Factors |

Examples of a Positive Approach to developmental factors to manage behavior |

|

Young SchoolAge |

Children this age: Are able to problem solve on their own Begin to understand responsibility Think in terms of fairness Attempt to negotiate

|

Fairness is a big issue for this group so working with this age group, a teacher should sit with children to develop “rules” and “consequences” so they can take ownership of behavioral expectations |

Pause to Reflect

What makes the most sense to you about guiding children’s behavior? What seems confusing to you?

IN CLOSING

It is of crucial importance that early childhood professionals have an understanding of the stages children move through at various ages. As our foundation, having this knowledge allows us to more effectively set expectations, plan interactions and curriculum, set up appropriate learning environments, and share information with parents that meets the current needs of the children we work with. Once we understand these general developmental patterns, we are able to move to understand individual children’s interests and abilities within this framework.

As we continue to build upon this chapter, a deep understanding of developmental ages and stages will be the cornerstone for Chapter 6 (Curriculum), Chapter 7 (Environments), and Chapter 8 (Partnering with Families). Referring back to these stages allows us to foster experiences and interactions geared toward children’s current abilities and strengths. Through this lens, we are able to see children for what they CAN do rather than what they cannot do YET, helping them move gradually from one stage to the next when they are ready.