CHAPTER 8 – PARTNERING WITH FAMILIES

|

Learning Objective Examine effective relationships and interactions between early childhood professionals, children, families, and colleagues, including the importance of collaboration. |

NAEYC STANDARDS

The following NAEYC Standard for Early Childhood Professional Preparation addressed in this chapter:

Standard 1: Promoting child development and learning

Standard 2: Building family and community relationships

Standard 5: Using content knowledge to build meaningful curriculum

Standard 6: Becoming a professional

PENNSYLVANIA EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATOR COMPETENCIES

The following competencies are addressed in this chapter:

Child Growth and Development

Families, Schools and Community Collaboration and Partnership

Professionalism and Leadership

Communication

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE EDUCATION OF YOUNG CHILDREN (NAEYC) CODE OF ETHICAL CONDUCT (MAY 2011)

The following elements of the code are touched upon in this chapter:

Section II: Ethical Responsibilities to Families

Ideals 2.1 – 2.9

Principles 2.1 – 2.15

PREVIEW

This chapter examines how we, as early childhood professionals, create important relationships with families to build effective home-school relationships. As a professional, we need to include families at the center of the work we do with their children. Valuing the input of families creates a sense of belonging that promotes success in school and home.

|

Unity Poem I dreamed I stood in a studio And watched two sculptors there, The clay they used was a young child’s mind And they fashioned it with care. One was a teacher; the tools she used were books and music and art; One was a parent with a guiding hand and a gentle loving heart. And when at last their work was done They were proud of what they had wrought. For the things they had shaped into the child Could never be sold or bought. And each agreed she would have failed If each had worked alone For behind the parent stood the school, And behind the teacher; the home. -Anonymous |

WORKING WITH FAMILIES

While most early childhood professionals choose to go into this field because they want to work with children, it is important to understand that those children come with families. Those families are the child’s first teacher and play a crucial role throughout that child’s life. In the early years, there will be much interaction between the child’s home and school environments and the important people in each.

In Chapter 1 (Theories), you may have noticed that the majority of the theories presented focused on the individual child and their development from “within”. Constructing knowledge; meeting basic needs; developing a sense of trust. These are all very important. Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological model took a different approach and looks at developmental influences outside of the child, and how they impact who the child becomes. One very important system is the child’s family. Children develop within the context of their families and the community that supports those families. As early childhood professionals, we build meaningful partnerships with the families of the children in our programs to ensure that their families are respected and valued in our program.

WHAT IS A FAMILY?

In its most basic terms, a family is a group of individuals who share a legal or genetic bond, but for many people, family means much more, and even the simple idea of genetic bonds can be more complicated than it seems.cx In your work with children, you will encounter many different types of family systems. All are as unique as the individual children that are part of them, and all need to feel that they can trust one of their most valuable assets to you.

|

Pause to Reflect Think about your family of origin. What did they “teach” you? How did they “shape” you? How important were they in who you are today? How does this relate to the families of the children you will work with? |

ETHICAL RESPONSIBILITIES TO FAMILIES

According to the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) Code of Ethical Conduct (May 2011) “families are of primary importance in children’s development. Because the family and the early childhood practitioner have a common interest in the child’s well-being, we acknowledge a primary responsibility to bring about communication, cooperation, and collaboration (the three C’s) between the home and early childhood program in ways that enhance the child’s development.”cxi

The code consists of ideals and principles that we must adhere to as ethical professionals. The ideals (refer to the Code of Ethical Conduct) provide us with how we need to support, welcome, listen to, develop relationships with, respect, share knowledge with and help families as we work together in partnership with them to support their role as parents. The principles provide us with specific responsibilities to families in our role as early childhood professionals. These principles include what individuals must do as well as the programs that serve those families.

|

Pause to Reflect After reviewing Section II – Ethical Responsibilities to Families in the NAEYC Code of Ethical Conduct, what stands out to you and why? What seems to make the most sense and why? What might be easy for you to uphold? What may be challenging? How can you use the code to shape your interactions with families? |

THE DIVERSITY OF TODAY’S FAMILIES

Figure 8.1 – This montage of photos shows a variety of families.cxii

The landscape of families has changed considerably over the last few decades. It is not that different types of families have never existed, but in today’s society, we are making places at the table for this diversity. The families that we serve in our early learning centers reflect this.

Types of Families:

Dual parent family

Single Parent

Grandparents or other relatives

Teen parents

Adoptive families

Foster families

Families with same-sex parents

Bi-racial/Multi-racial families

Families with multi-religious/faith beliefs

Children with an incarcerated parent(s)

Unmarried parents who are raising children

Transgender parents raising children

Blended families

Multigenerational Families

Families formed through reproductive technology

First-time older parents

Families who are homeless

Families with children who have developmental delays and disabilities

Families raising their children in a culture not their own

The list above is extensive; however, other family systems you will encounter in your work with children’s families, are all worthy of respect and understanding. For a definition of the types of families listed above, refer to the Appendix.

|

Pause to Reflect As an early childhood professional, why might it be important to understand each of these family structures? |

PARENTING STYLES

In addition to the types of families we will work with, there will also be different parenting styles within those families. Diana Baumrind, looking at the demands parents place on their children and their responsiveness to their child’s needs, placed parenting into the following categories:

Authoritarian Parenting Style: Authoritarian parenting is a strict style in which parents set rigid rules and high expectations for their children but do not allow them to make decisions for themselves. When rules are broken, punishments are swift and severe. It is often thought of as “my way or the highway” parenting.

Authoritative Parenting Style: Authoritative parents provide their children with boundaries and guidance, but give their children more freedom to make decisions and learn from their mistakes. It is referred to as a more democratic approach to parenting.

Permissive Parenting Style: Permissive parents give their children very few limits and have more of a peer relationship than a traditional parent-child dynamic. They are usually super-responsive to their kids’ needs and give in to their children’s wants. Today we use the term “helicopter or lawnmower parenting.”

Neglectful Parenting Style: A style added later by researchers Eleanor Maccoby and John Martin, neglectful parents do not interact much with their children, placing no limits on their behavior but also failing to meet their needs.cxiii

While this research suggested that children raised with authoritative parents have better outcomes, we must be careful not to rush to judgment when working with families. Our style of parenting is deeply rooted in how our parents raised us. As early childhood professionals, we have the opportunity to collaborate with families to join in working together for the betterment of their children, while considering culture, personality, and other circumstances.

|

Pause to Reflect What parenting styles did your parents use with you? Do you see yourself using any of these styles as a teacher? Why or why not? |

STAGES OF PARENTING

Ellen Galinsky traced six distinct stages in the life of a parent in relation to their growing child. Much like how a child moves through stages. By looking at these different stages of parenting, those who work with children and youth can gain some insight into parental needs and concerns. cxiv

Table 8.1: Stages of Parenting

|

|

Age of Child |

Main Tasks and Goals |

|

Stage 1: The ImageMaking Stage |

Planning for a child; pregnancy |

Consider what it means to be a parent and plan for changes to accommodate a child. |

|

Stage 2: The Nurturing Stage |

Infancy |

Develop an attachment to the child and adapt to the new baby. |

|

Stage 3: The Authority Stage |

Toddler and preschool |

Parents create rules and figure out how to effectively guide their child’s behavior. |

|

Stage 4: The Interpretive Stage |

Middle Childhood |

Parents help their children interpret their experiences with the social world beyond the family. |

|

Stage 5: The Interdependence Stage |

Adolescence |

Parents renegotiate their relationship with adolescent children to allow for shared power in decision-making. |

|

Stage 6: The Departure Stage |

Early adulthood |

Parents evaluate their successes and failures as parents.

|

|

Pause to Reflect How does understanding these stages assist in your work with parents?

|

VALUING FAMILIES THROUGH REFLECTIVE PRACTICE

Previous chapters have introduced reflection as a process we engage in to better ourselves, our practices, and by extension our programs. Working with families will bring an additional piece to our reflection as we continue to understand our values and beliefs and how they affect the way, we view different families. Are we feel more comfortable with some family structures over other family structures? Do we agree with certain family discipline techniques and not others? Do we connect with some families more than others?

These are all-natural; after all, we all come from a family that has instilled certain beliefs and mindsets in us. Having these feelings is expected; acting upon them as an early childhood professional is different. All family members deserve respect and to feel valued. Just because they do something differently does not necessarily make it “wrong”. We do not know what happens in a full day with that family any more than they know what happens in yours. We get a glimpse into the small portion they want to share with us, which may or may not be indicative of the rest of the picture. If we approach our families with a reflective lens, we can do much to understand and truly collaborate with them.

To begin this process, it is helpful to consider the following questions:

How can I learn more about that family?

What kinds of opportunities can I provide for families to be a part of their child’s classroom experience?

How can I help all families feel connected, respected, and valued?

What judgments/assumptions do I have about different family structures? How do those judgments/assumptions get in the way of me connecting with all of my families?

|

Pause to Reflect Which of these questions resonate with you? Are there others you might add? |

Previous chapters have also repeatedly emphasized the importance of establishing relationships; providing a warm, safe, and trusting environment; and creating long-term connections with the children we work with. By extension, we can employ those same measures for each family member. A family is entrusting you with a very large and special portion of their life, often with very little knowledge of who you are. Finding ways to help them feel secure in their decision will go a long way toward bridging the two most important worlds of a child’s existence.

|

Pause to Reflect What strategies that you have already considered using to make children feel comfortable and valued might you use with their families?

|

To serve families holistically requires a shift in our thinking. It is common for teachers to feel as if they are the experts, and that parents bring their children to us for our expertise. While this may be partially true, we need to understand that although we may be the experts in the way children develop and learn in general, parents are equal experts in their particular child. This acceptance of two complementary but different types of knowledge allows us to form true partnerships with families. It allows all parties to be better than they would on their own. How exciting it is, to learn from families all that they have to offer! How wonderful for a child to know that everyone is behind them, supporting them in the ways that they know best.

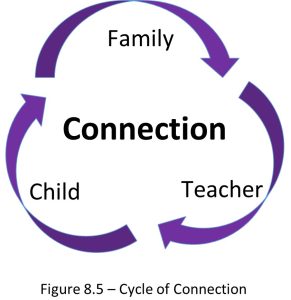

Figure 8.2 – The relationship between family and teacher centers on the child

PLANNING PARTNERSHIPS

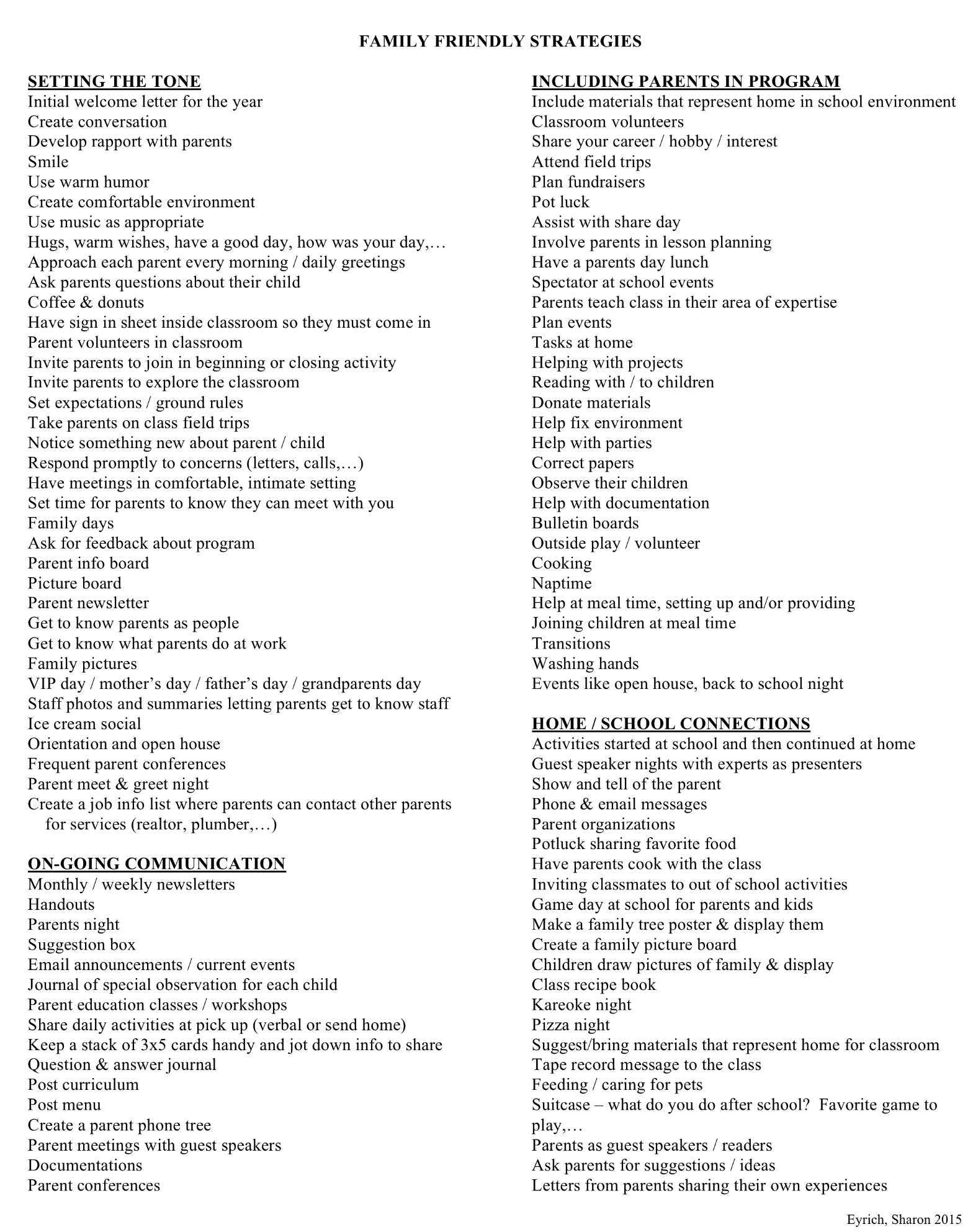

As we learned in Chapters 6 (Curriculum) and 7 (Environments), planning can be quite valuable for many aspects of our early childhood programs. Planning to include families will be no different. Usually, teachers consider the following to collaborate with families throughout the year:

Setting the tone (making connections to help families feel included and comfortable)

On-going communication (valuing this crucial process throughout the school year)

Including families in the program (drawing on their expertise, experiences, and support)

Home-School Connections (extending experiences between home and school)

Figure 8.3 – Family Friendly Strategiescxv

BEHAVIOR AS IT RELATES TO FAMILY

The NAEYC Code of Ethical Conduct states I-2.6 – To acknowledge families’ childrearing values and their right to make decisions for their children.cxvi There are many conflicting messages about how to raise children effectively today. When we listen to the concerns of families, we are better equipped to offer them educational experiences that can open their hearts and their minds to other ways of raising their children. (Refer to the list of parenting resources at the end of this chapter). It is important to be mindful that there are many ways to effectively parent. Noting that will help early childhood professionals to have respect for differences in all aspects of our field.

In addition, behavioral expectations vary from culture to culture. Behavior can be verbal, expressive, non-verbal, or non-expressive. Our role is to understand what the child is telling us by their behavior and to provide the necessary guidance that elevates the child and their family’s sense of being.

Pause to Reflect What behavior expectations did your family have for you as a child? How does that differ from other people in your life? What judgments do you hold about those behavioral expectations? How could those judgments affect the relationships you want to build with families? |

FAMILY EDUCATION

One of the important roles of early childhood professionals is to provide opportunities for families to gain more skills in the role of parents. We accomplish this by using various strategies that work for each of the families that we serve.

These strategies may include:

Family workshops – we offer these workshops to families who may want to have more information about parenting. At the beginning of the school year, you can send a questionnaire home to inquire about what the families at your center may want to know more about in their role as parents. Facilitation of these workshops by center staff/administration, by other professionals who work closely with children and families, or by professional family educators provide a diverse lens through which to support families in their quest for support and information.

Meeting with families – families often parent in isolation and need support in their role as parents. The teacher can offer to meet with them to listen to their concerns and share ideas with them. This is accomplished in the context of understanding, compassion, and respect for the role that families play.

Support groups for families – You may want to consider providing opportunities for parents to provide support to each other. You can accomplish this by creating a space for parents to meet both formally and informally. This helps to engender agency in families and to create parent leaders.

Newsletters – provide families with parenting resources in a newsletter. You can write articles about specific parenting topics that the families at the center have identified. You can provide links to reputable parenting sites.

Providing community resources to families – the Code of Ethical Conduct speaks directly to this. In I-2.9 it says: To foster families’ efforts to build support networks and, when needed, participate in building networks for families by providing them opportunities to interact with program staff, other families, community resources, and professional services. P-2.15 states – We shall be familiar with and appropriately refer families to community resources and professional support services. After a referral has been made, we shall follow up and ensure that services have been appropriately provided. cxvii

Resource library – provide families with materials that they can check out. These resources could be parenting books, parenting articles, or parenting curriculum.

Pause to Reflect These are just a few of the many ways we can provide families with education and support that can assist them in their parenting journey. In reviewing this section, what additional ideas do you have that excite you in educating parents? |

COMMUNICATING WITH FAMILIES

According to NAEYC’s – 5 Guidelines for Effective Teaching, the fifth guideline states “Establish reciprocal relationships with families.” Effective communication begins with cultivating a trusting and mutually respectful relationship. As a best practice, teachers must strive to make family members feel like they are valued members of the team. Teachers must strive to encourage open lines of regular communication and should collaborate whenever possible, especially when it comes to making important decisions about their child. It is ultimately the teacher’s responsibility to set the tone that lets families know a partnership is highly valued. In this section, we will review what effective communication entails, and we will look at how to prepare for family conferences. cxviii

Sharing Perspectives

Effective communication is based on respect for others. When we have regard for other people’s perspectives, we are able to show genuine respect and can cultivate a caring classroom community. Perspectives are personal viewpoints that allow us to make sense of the world we live in. We develop our attitudes, beliefs, and biases based on our own knowledge, experiences, family history, cultural practices, and interactions we have throughout our lives. Both teachers and families make crucial decisions on how to guide and support children based on their own perspectives. Without realizing it, our perspectives can influence the way we interact and judge others. If we recognize our biases and try to understand that everyone is entitled to their own perspective, we can strive to develop respectful relationships with our families as we continue to support children’s development. Let us look at the valuable contributions both teachers and families bring to the relationship.

|

Pin It! What Teachers and Families Bring Teachers bring: information about the child based on observation and assessment information about the child’s developmental performance information about the curriculum activities and learning goals for the child knowledge about the best practices, theory, and principles in early childhood information about the program’s philosophy, job description, agency policies their own unique personality and temperament their own training, experience, and professional philosophy Families bring: an understanding of the child’s temperament, health history, and behaviors at home expectations, fears, and hopes about the child’s success or failure culturally-rooted beliefs about child-rearing past experiences and beliefs about school parent/caregivers’ sense of control and authority, and other personal and familial influences. |

Developing a Collaborative Partnership

As you engage in conversations, be aware that you communicate with your words, as well as your actions and body language. How can you create a warm and welcoming vibe that encourages open communication with families?

A smile goes a long way. Make every attempt to greet each family at drop-off time and be sure to say goodbye when they pick up their child.

Family Questionnaires. It is important to realize that children come from diverse family settings and we should never assume to know the unique dynamics. In most cases, a child’s home life is the child’s first “classroom” and the parents are the child’s first “teacher.” A questionnaire will provide useful insight and background information that you will need to approach the family more responsively.

Offer anecdotes. Families appreciate hearing about special moments that occur in their child’s day. Some parents may feel guilty or may struggle with missing out on those milestone moments. To help families feel connected, share those moments whenever possible.

Have opportunities for families to volunteer. Include opportunities where families can get involved both in and out of the classroom setting.

Have a system in place for ongoing communication. Consider how you will share all that is happening at school and think about how families can inform you about what is happening at home. Some programs use handouts, emails, bulletin boards, and file folders to relay messages.

Share your ECE knowledge. Keep in mind that childrearing practices are embedded in cultural practices. When we recognize that every family is doing the best that they can and wants the best for their children, we can provide support to families that match their needs. Some families will need more support than others will. Provide parenting resources (handouts, books) and post information on community services (food pantries, free events, counseling) for your families.

Maintain confidentiality and keep sensitive information private. Monitor what you say and write and NEVER share information about other families. Keep all documents, assessments, and important information stored in a safe place.

Honesty is the best policy. Be direct and tell the truth (which is sometimes easier said than done). It is a good practice that if a parent asks you something and you do not have the answer- tell them you will have to get back to them. Guessing or giving inaccurate information can ultimately break down communication.

Follow through. When you and a parent agree upon something (to talk at a certain time or to implement a new guidance strategy) be sure you do your part to keep up with the agreement.cxx

|

Pause to Reflect Do these make sense to you? Why or why not? What would you add? |

Effective Family Conferences

The purpose of conferences with families is for both teachers and families to share information about the child and to find ways to foster continued growth. To ensure that family members understand the purpose of the assessment process, you may want to create a handout that explains what family conferences look like at your center and what your goals are as the teacher. Be mindful that many families work and may find it difficult to engage in a traditional face-to-face conference. We recommend that you provide alternative ways to communicate with families to discuss their child’s progress.

Here are some other tips and recommendations to consider when planning effective family conferences:

Create a welcoming conference space. Set up a private space for the conference and arrange chairs side by side. Provide light snacks and beverages to help families feel more comfortable and relaxed during the conference.

Be Prepared. Preparation is vital to conducting a successful conference. Take time to review the child’s work and make notes of what you want to discuss during the conference. Prepare any handouts/resources you may want to give to families at the meeting. Have the child’s portfolio up to date and in pristine condition.

Start the conference with a positive comment or question. Families are often anxious about what teachers will say about their child, so start the conference with a positive comment and let them know you appreciate them being there. Ask a question to open the dialogue (this will also let you know what is important to the family and what to focus on).

Knowing the family’s expectations will help guide your conference. Ask the family for input on their child’s strengths and needs, behavior, and learning styles. Actively listening to the family will help you learn more about the child and his or her home life. This will help you better understand the hopes and goals the family has for their child.

Remember that you are not a professional counselor, therapist, or social worker. Some families may want to tell you about their personal family matters, or about the challenging situations, they are facing. Keep social service resources on hand and have them readily available to give to your families.

Stay focused. Conferences can easily get off-topic for one reason or another. The child’s development is the purpose of the conference, so circle back around as needed to keep the conference on track.

Ask open-ended questions. This will facilitate conversation and encourage families to engage and participate during the conference.

Use family-friendly terms and avoid professional jargon. We want to make sure that families understand what we are telling them. We use professional jargon with our colleagues/co-workers. We may even consider colleagues as professional jargon. Remembering that families did not study child development will help us to use family-friendly terms in all of our communications with families.

Have an inclusive support team on hand. Some families may not speak English and may need someone available to translate information.

Engage families in the planning process. To further support their child’s development, families will need practical activities to do at home. Discuss ways to tie in what efforts are being made at school with activities that can be done at home.

Be reassuring. Families are not usually aware that there is a range of mastery

when it pertains to developmental milestones.

Be professional. You must always use professional verbal and written communication skills when dealing with families

Be sensitive. When dealing with children who have special needs, put the person before the disability. Make sure family members are familiar with any important terms and that they understand questions or statements about their child’s abilities. Have resources available.

Focus on strengths and what the child can do. Families appreciate looking at their children from a strength-based lens. That perspective builds trust with families to enable them to hear everything that they need to know about their child in an early learning environment.

Schedule a follow-up if needed. Schedule a follow-up meeting as needed if the family has concerns or to check in on the child’s progress. This is also best practice with all families as a follow-up could be merely an informal check-in when dropping off or picking up.

End the conference on a positive note. Thank all family members for coming to the conference. Stress collaboration and continued open communication. Let families know their support is needed and appreciated. Express confidence in the child’s abilities to continue to learn and develop. Share at least one encouraging anecdote or positive comment about the child to end the conference. cxxi

Figure 8.6 – A family conference in action.cxxii

Trauma-Informed Care xxi

Over the last few decades, we have seen an increase in childhood trauma. Many types of trauma have a lasting effect on children as they grow and develop. When we think of trauma, we may think of things that are severe; however, we know that trauma comes in small doses that are repeated over time.

There has been much research done to help identify what these adverse childhood experiences are. The compilation of research has identified some traumatic events that occur in childhood (0 – 17 years) that have an impact on children’s well-being that can last into adulthood if not given the proper support to help to mitigate this trauma. Here is a list of some of the traumatic events that may impact children’s mental and physical well-being: xxii

Experiencing violence or abuse

Witnessing violence in the home or community

Having a family member attempt or die by suicide

Also including are aspects of the child’s environment that can undermine their sense of safety, stability, and bonding such as growing up in a household with:

Substance misuse

Mental health problems

Emotional abuse or neglect

Instability due to parental separation or household members being in jail or prison

|

Pause to Reflect… COVID-19 Trauma How may COVID-19, with the disruptions, isolations, and uncertainty contribute to trauma in early childhood? |

These adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are linked to chronic health problems, mental illness, and substance abuse in adulthood, and have a negative impact on educational and job opportunities.

Here are some astounding facts about ACEs:

ACEs are common. About 61% of adults surveyed across 25 states reported that they had experienced at least one type of ACE, and nearly 1 in 6 reported they had experienced four or more types of ACEs.

Preventing ACEs could potentially reduce a large number of health conditions. For example, up to 1.9 million cases of heart disease and 21 million cases of depression could have been potentially avoided by preventing ACEs.

Some children are at greater risk than others. Women and several racial/ethnic minority groups were at greater risk for having experienced 4 or more types of ACEs.

ACEs are costly. The economic and social costs to families, communities, and society total hundreds of billions of dollars each year.

Trauma Informed Care is an organizational structure and treatment framework that involves understanding, recognizing, and responding to the effects of all types of trauma. Trauma Informed Care also emphasizes physical, psychological, and emotional safety for both consumers and providers, and helps survivors rebuild a sense of control and empowerment.

What can we do in our early childhood programs? We can help to ensure a strong start for children by:

Creating an early learning program that supports family engagement.

Make sure we are providing a high-quality child care experience.

Support the social-emotional development of all children.

Provide parenting workshops that help to promote the skills of parents.

Use home visitation as a way to engage and support children and their families.

Reflect on our own practices that could be unintentionally harmful to children who have experienced trauma.

What can we do in our community? As early childhood professionals, our ethical responsibilities extend to our community as well (NAEYC Code of Ethical Conduct, May, 2011):

Be a part of changing how people think about the causes of ACEs and who could help prevent them.

Shift the focus from individual responsibility to community solutions.

Reduce stigma around seeking help with parenting challenges or for substance misuse, depression, or suicidal thoughts.

Promote safe, stable, nurturing relationships and environments where children live, learn, and play

IN CLOSING

As early childhood professionals, we need to include families at the center of the work we do with their children. Valuing their input creates a sense of belonging that promotes success in school and at home. Understanding the unique systems, styles, and stages of each of the family members we welcome into our program enables us to collaborate more fully with each of them, providing the type of collaborative expertise that enhances each partner beyond their individual capacity.

|

Quotable “Children thrive when they have the skills they need to succeed and when families are meaningfully involved in their development and learning.” – Bierman, Morris, & Abenavolicxxiii |