CHAPTER 2 – DEVELOPMENTAL AND LEARNING THEORIES

|

Learning Objective Examine historical and theoretical frameworks as they apply to current early childhood practices.

|

NAEYC STANDARDS

The following NAEYC Standard for Early Childhood Professional Preparation are addressed in this chapter:

Standard 1: Promoting child development and learning

Standard 5: Using content knowledge to build meaningful curriculum

Standard 6: Becoming a professional

PENNSYLVANIA EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATOR COMPETENCIES

Child Growth and Development

Families, Schools and Community

Curriculum and Learning Experiences

Observation, Screening, Assessment, and Documentation

Communication

Professionalism and Leadership

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE EDUCATION OF YOUNG CHILDREN (NAEYC) CODE OF ETHICAL CONDUCT (MAY 2011)

The following elements of the code are touched upon in this chapter:

Section I: Ethical Responsibilities to Children Ideals: – I-1.1 through I-1.11

Principles: P-1.1, P-1.2, P – 1.3, P-1.7

Section IV: Ethical Responsibilities to Community and Society

Ideals: I:4.1, I-4.6, I-4.8

PREVIEW

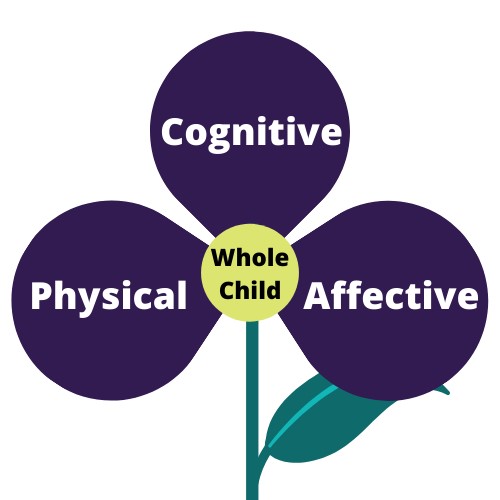

This chapter begins with the developmental and learning theories that guide our practices with young children who are in our care. The theories presented in this chapter help us to better understand the complexity of human development. The chapter concludes by looking at some of the current topics about children’s development that inform and influence the field. With this valuable insight, we can acquire effective strategies to support the whole child – physically, cognitively, and affectively.

Quotable:

“It is easier to build strong children than to repair broken adults.”

– F. Douglas

WHAT IS A THEORY AND WHY IS IT IMPORTANT?

As with the historical perspectives that were discussed in Chapter 1, theories provide varied and in-depth perspectives that can be used to explain the complexity of human development. Human development is divided into 3 main areas: Physical, Cognitive, and Affective. Together these address the development of the whole child.

Physical-motor development – this includes our gross motor, fine motor, and perceptual-motor.v

Cognitive or intellectual development – this includes our thoughts and how our brain processes information, as well as utilizes language so that we can communicate with one another.vi

Affective development – this includes our emotions, social interactions, personality, creativity, spirituality, and the relationships we have with ourselves and others.vii

All three areas of development are of critical importance in how we support the whole child. For example, if we are more concerned about a child’s cognitive functioning we may neglect to give attention to their affective development. We know that when a child feels good about themselves and their capabilities, they are often able to take the required risks to learn about something new to them. Likewise, if a child is able to use their body to learn, that experience helps to elevate it to their brain.

Quotable:

“If it isn’t in the body, it can’t be in the brain.” – Bev Boss

“Students who are loved at home come to school to learn, and students who aren’t, come to school to be loved.” – Nicholas A. Ferroni

Figure 2.1 Whole Child Flower. viii

Theories help us to understand behaviors and recognize developmental milestones so that we can organize our thoughts and consider how to best support a child’s individual needs. With this information, we can then plan and implement learning experiences that are appropriate for the development of that child (called, “developmentally appropriate practice, which is discussed more later in this chapter), set up engaging environments, and most importantly, we can develop realistic expectations based on the child’s age and stage of development.

A theory is defined as “a supposition, or a system of ideas intended to explain something, especially one based on general principles independent of the thing to be explained, a set of principles on which the practice of an activity is based.”ix

The theories we chose to include in this text form the underlying “principles” that guide us in the decisions we make about the children in our care, as well as provide us with insight on how to best support children as they learn, grow, and develop. The theories that have been selected were proposed by scientists and theorists who studied human development extensively. Each, with its own unique hypothesis, set out to examine and explain development by collecting data through observations/experiments. The theorists we selected, strived to answer pertinent questions about how we develop and become who we are. Some sought to explain why we do what we do, while others studied when we should achieve certain skills. Here are a few of the questions developmental theorists have considered:

Is development due to maturation or due to experience? This is often described as the nature versus nurture debate. Theorists who side with nature propose that development stems from innate genetics or heredity. It is believed that as soon as we are conceived, we are wired with certain dispositions and characteristics that dictate our growth and development. Theorists who side with nurture claim that it is the physical and temporal experiences or environment that shape and influence our development. It is thought that our environment -our socioeconomic status, the neighborhood we grow up in, and the schools we attend, along with our parents’ values and religious upbringing impact our growth and development. Many experts feel it is no longer an “either nature OR nurture” debate but rather a matter of degree; which influences development more?

Does one develop gradually or does one undergo specific changes during distinct time frames? This is considered a continuous or discontinuous debate. On one hand, some theorists propose that growth and development are continuous; it is a slow and gradual transition that occurs over time, much like an acorn growing into a giant oak tree. While on the other hand, there are theorists that consider growth and development to be discontinuous; which suggests that we become different organisms altogether as we transition from one stage of development to another, similar to a caterpillar turning into a butterfly.

|

Pause to Reflect Think about your own growth and development. Do you favor one side of the nature vs nurture debate? Which premise seems to make more sense – continuous or discontinuous development? Take a moment to jot down some ideas. Your ideas help to create opportunities to deepen our understanding and to frame our important work with young children and their families.? |

As suggested earlier, not only do theories help to explain key components of human development, but theories also provide practitioners with valuable insight that can be utilized to support a child’s learning, growth, and development. At this time, we would like to mention that although theories are based on notable scientific discoveries, it is necessary to emphasize the following:

No one theory exclusively explains everything about a child’s development.

Theories are designed to help us make educated guesses about children’s development • Each theory focuses on a different aspect of human development

Theories often build on previous theoretical concepts and may seek to expand ideas or explore new facets.

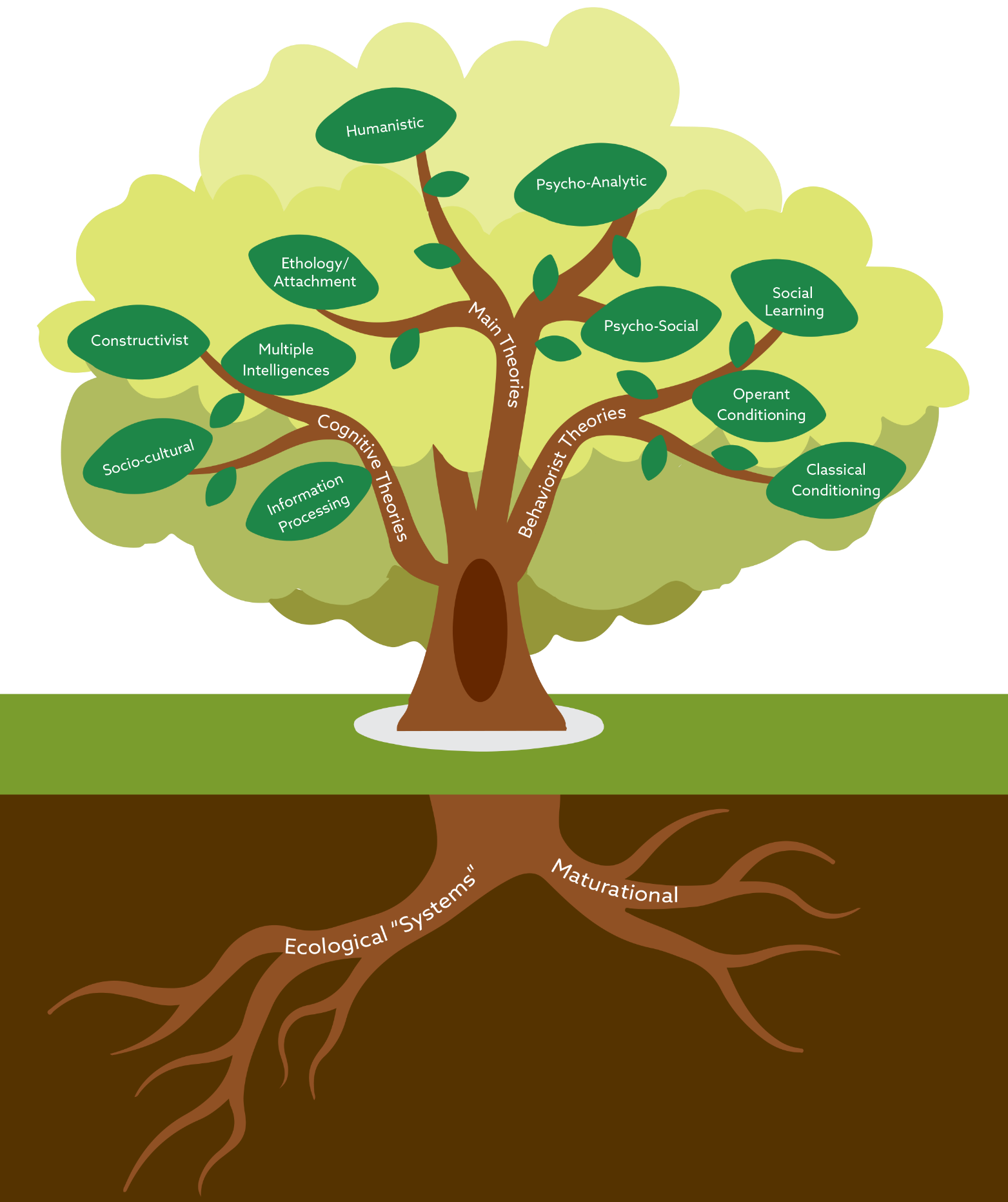

Let’s take a look at the theories:

Figure 2.2 The Theory Tree.x

We are going to break it up as follows:

Table 2.1 Roots – Foundational Theoriesxi

|

Theory |

Key Points |

Application |

|

Maturational Arnold Gesell 1880 – 1961 |

All children move through stages as they grow and mature On average, most children of the same age are in the same stage There are stages in all areas of development (physical, cognitive, language, affective) You can’t rush stages |

There are “typical” ages and stages Understand current stage as well as what comes before and after Give many experiences that meet the children at their current stage of development When child is ready they move to the next stage |

|

Ecological “Systems” Urie Bronfenbrenner 1917 – 2005 |

There is broad outside influence on development (Family, school, community, culture, friends ….) There “environmental” influences impact development significantly |

Be aware of all systems that affect child Learning environment have impact on the developing child Home, school, community are important Supporting families supports children |

This content was created by Sharon Eyrich. It is used with permission and should not be altered.

Table 2.2 Branches – Topical Theories xii

|

Theory |

Key Points |

Application |

|

Psycho-Analytic Sigmund Freud 1856 – 1939 |

Father of Psychology Medical doctor trying to heal illness We have an unconscious Early experiences guide later behavior Young children seek pleasure (id) Ego is visible; when wounded can get defensive Early stages of development are critical to healthy development |

Understand unconscious motivations Create happy and healthy early experiences for later life behaviors Know children are all about “ME” Expect ego defenses Keep small items out of toddlers reach Treat toileting lightly |

|

Psycho-Social Erik Erikson 1902 – 1994 |

• Relationships are crucial and form the social context of personality |

• Provide basic trust (follow through on promises, provide stability and consistency, …) |

|

Theory |

Key Points |

Application |

|

|

Early experiences shape our later relationships and sense of self Trust, autonomy, initiative – are the early stages of development Humans like to feel competent and valued

|

Create a sense of “belongingness” Support autonomy and exploration Help children feel confident Encourage trying things and taking safe risks See mistakes as learning opportunities |

|

Humanistic Abraham Maslow 1908-1970

|

We have basic and growth needs Basic needs must be met first We move up the pyramid toward self-actualization |

Make sure basic needs like nutrition, sleep, safety is taken care of Understand movement between needs Know needs may be individual or as a group |

|

Ethology/Attachme nt John Bowlby 1907-1990 Mary Ainsworth 1913 – 1999 |

Biological basis for development Serve evolutionary function for humankind There are sensitive periods Attachment is crucial for survival Dominance hierarchies can serve survival function |

Understand evolutionary functions Offer positive and appropriate opportunities doing sensitive periods Facilitate healthy attachments

|

This content was created by Sharon Eyrich. It is used with permission and should not be altered.

Table 2.3 Branches – Cognitive Theories xiii

|

Theory |

Key Points |

Application |

|

Constructivist Jean Piaget 1896 – 1980 |

We construct knowledge from within Active learning and exploration Brains organize and adapt Need time and repetition Distinct stages (not miniadults) Sensory-motor, preoperational |

Provide exploration and active learning Ask open ended questions/promote thinking Repeat often Don’t rush Allow large blocks of time Value each unique stage Provide sensory and motor experiences Provide problem solving experience |

|

Theory |

Key Points |

Application |

|

Socio-cultural Lev Vygotsky 1896 – 1934 |

Learning occurs within a social context Scaffolding – providing appropriate support to increase learning “Zone of proximal development” = “readiness to learn” something |

Provide appropriate adultchild interactions Encourage peer interactions Provide a little help, then step back Understand when a child is ready; don’t push them or do it for them |

|

Information Processing (Computational Theory) 1970 – |

Brain is like a computer Input, process, store, retrieve Early experiences create learning pathways Cortisol – stress hormone shuts down thinking Endorphins – “happy” hormone, increases learning

|

Develop healthy brains (nutrition, sleep, exercise) Decrease stress, increase happiness Know sensory input (visual, auditory ….) Understand individual differences Allow time to process |

|

Multiple Intelligences Howard Gardner 1943 – |

• Once information enters the brain, each brain processes information differently |

Provide learning experiences to meet a wide range of learning styles Help learners learn how they learn best Offer many experiences in a variety of ways |

This content was created by Sharon Eyrich. It is used with permission and should not be altered.

Table 2.4 Branches – Behaviorist Theories

|

Theory |

Key Points |

Application |

|

Classical Conditioning Ivan Pavlov 1849 – 1936 |

We respond automatically to some stimuli When we pair a neutral stimulus with the one that elicits a response we can train the subject to respond to it Over time we can “un-pair” stimulus and response |

Be aware of conditioning Pair stimuli to elicit desired responses Look for pairings in undesirable behaviors

|

|

Operant Conditioning B. F. Skinner 1904 – 1990 |

Behavior is related to consequences Reinforcement/Rewards/Punis hment Goals of behavior (motivators) |

Understand what is motivating behavior Reinforce behavior we want Don’t reinforce behavior we don’t want Consider small increments |

|

Theory |

Key Points |

Application |

|

Social Learning Albert Bandura 1925 –

|

Children (and adults) learn through observation Children (and adults) model what they see |

Know what children are watching Model what you want children to do |

This content was created by Sharon Eyrich. It is used with permission and should not be altered.

CURRENT DEVELOPMENTAL TOPICS TO INFORM OUR PRACTICE WITH CHILDREN AND FAMILIES

Brain Functioning

In the 21st century, we have medical technology that has enabled us to discover more about how the brain functions. “Neuroscience research has developed sophisticated technologies, such as ultrasound; magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); positron emission tomography (PET); and effective, non-invasive ways to study brain chemistry (such as the steroid hormone cortisol).” xiv These technologies have made it possible to investigate what is happening in the brain, both how it is wired and how the chemicals in our brain affect our functioning. Here are some important aspects, of this research, for us to consider in working with children and families:

Rushton (2011) provides these four principles that help us to connect the dots to classroom practice:

Principle #1: “Every brain is uniquely organized” When setting up our environments, it is important to use this lens so we can provide varied materials, activities, and interactions that are responsive to each individual child. (We expand on this in Chapter 5 – Developmental Ages and Stages/Guidance).

Principle #2: “The brain is continually growing, changing, and adapting to the environment.”

The brain operates on a “lose it or use it” principle. Why is this important? We know that we are born with about 100 billion brain cells and 50 trillion connections among them. We know that we need to use our brains to grow those cells and connections or they will wither away. Once they are gone, it is impossible to get them back.

o Children who are not properly nourished, both with nutrition and stimulation suffer from the deterioration of brain cells and the connections needed to grow a healthy brain.

o Early experiences help to shape the brain. Attunement (which is a bringing into harmony,) with a child, creates that opportunity to make connections.

Principle #3: “A brain-compatible classroom enables connection of learning to positive emotions.”

Give children reasonable choices.

Allow children to make decisions. (yellow shovel or blue shovel, jacket on or off, etc.)

Allow children the full experience of the decisions they make. Mistakes are learning opportunities. (F.A.I.L. – First attempt in learning). Trying to do things multiple times and in multiple ways provides children with a healthy self-image.

Principle #4: “Children’s brains need to be immersed in real life, hands-on, and meaningful learning experiences that are intertwined with a commonality and require some form of problem-solving.”

Facilitate the exploration of children’s individual and collective interests.

Give children the respect to listen and engage regarding their findings.

Give children time to explore.

Give children the opportunity to make multiple hypotheses about what they are discovering.

Developmentally Appropriate Practices

The National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC), one of the professional organizations in the field of early childhood education, has a position statement from 2020: https://www.naeyc.org/resources/positionstatements/dap. There are three important aspects of Developmentally Appropriate Practices (DAP): xv

Commonality—current research and understandings of processes of child development and learning that apply to all children, including the understanding that all development and learning occur within specific social, cultural, linguistic, and historical contexts.

Individuality—the characteristics and experiences unique to each child, within the context of their family and community, that have implications for how best to support their development and learning.

Context—everything discernible about the social and cultural contexts for each child, each educator, and the program as a whole.

What does this mean?

Utilizing the core components of DAP is important for practitioners of early learning. Here are some things to consider:

When considering commonalities in development and learning, it is important to acknowledge that much of the research and the principal theories that have historically guided early childhood professional preparation and practice have primarily reflected norms based on a Western scientific-cultural model. Little research has considered a normative perspective based on other groups. As a result, differences from this Western (typically White, middle-class, monolingual English-speaking) norm have been viewed as deficits, helping to perpetuate systems of power and privilege and to maintain structural inequities. Increasingly, theories once assumed to be universal in developmental sciences, such as attachment, are now recognized to vary by culture and experience. The current body of evidence indicates that all child development and learning—actually, all human development and learning— are always embedded within and affected by social and cultural contexts. To be an effective early childhood professional, we must use a variety of methods – such as observation, clinical interviews, examination of children’s work, individual child assessments, and talking with families so we get to know each individual child in the group well. When we have compiled the information we need to support each child, we can make plans and adjustments to promote each child’s individual development and learning as fully as possible.

Educators understand that each child reflects a complex mosaic of knowledge and experiences that contributes to the considerable diversity among any group of young children. These differences include the children’s various social identities, interests, strengths, and preferences; their personalities, motivations, and approaches to learning; and their knowledge, skills, and abilities related to their cultural experiences, including family languages, dialects, and vernaculars. Children may have disabilities or other individual learning needs, including needs for accelerated learning. Sometimes these individual learning needs have been diagnosed, and sometimes they have not. Early childhood educators recognize this diversity and the opportunities it offers to support all children’s learning by recognizing each child as a unique individual with assets and strengths to contribute to the early childhood education learning environment.

Context includes both one’s personal cultural context (that is, the complex set of ways of knowing the world that reflect one’s family and other primary caregivers and their traditions and values) and the broader multifaceted and intersecting (for example, social, racial, economic, historical, and political) cultural contexts in which each of us live. In both the individual- and societal definitions, these are dynamic rather than static contexts that shape and are shaped by individual members as well as other factors. Early childhood educators must also be aware that they themselves—and their programs as a whole—bring their own experiences and contexts, in both the narrower and broader definitions, to their decision-making. This is particularly important to consider when educators do not share the cultural contexts of the children they serve.

(More content will be in Chapters 4, 5, and 6 that will help you to deeply understand DAP)

To summarize how to make use of DAP, an effective teacher begins by thinking about what children of that chronological and developmental age are like. This knowledge provides a general idea of the activities, routines, interactions, and curriculum that will be effective with that group of children. The teacher must also consider how each child is an individual within the context of family, community, culture, linguistic norms, social group, past experience, and current circumstances. Once the teacher can fully see children as they are, they are able to make decisions that are developmentally and culturally appropriate for each of the children in their care.

Identity Formation

Who we are is a very important aspect of our well-being. As children grow and develop, their identity is shaped by who they are when they arrive on this planet and the adults and peers whom they interact with throughout their lifespan. Many theories give us supportive evidence that helps us to see that our self-concept is critical to the social and emotional health of human beings. (ex. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, Erikson’s Psychosocial Theory, John Bowlby’s Attachment Theory, etc.) As early childhood professionals, we are called upon to positively support the social/emotional development of the children and the families that we serve. We do this by:

Honoring each unique child and the family they are a part of.

Acknowledging their emotions with attunement and support.

Listening to hear not to respond.

Providing an emotionally safe space in our early childhood environments.

Recognizing that all emotions are important and allowing children the freedom to express their emotions while providing them the necessary containment of safety.

Our social-emotional life or our self-concept has many aspects to it. We are complex beings and we have several identities that early childhood professionals need to be aware of when interacting with the children and families in their early childhood environments. Our identities include but are not limited to the following categories:

Gender

Ethnicity

Race

Economic Class

Sexual Identity

Religion

Language

(Dis)abilities

Age

Understanding our own identities and that we are all unique, helps us to build meaningful relationships with children and families that enable us to have understanding and compassion. Being aware (using reflective practice) that all humans are diverse and our environments, both emotionally and physically, need to affirm all who come to our environments to learn and grow.

While we begin to form our identities from the moment we are conceived, identity formation is not stagnant. It is a dynamic process that develops throughout the lifespan. Hence, it is our ethical responsibility as early childhood professionals to create supportive language, environments, and inclusive practices that will affirm all who are a part of our early learning programs.

While we delve more into guiding the behavior of young children in Chapter 5, there is evidence that when children feel supported and accepted by adults for who they are, this helps to wire and equip the brain for self-regulation. As we model regulation behavior (this is often identified as co-regulation behavior) which includes acceptance, compassion, belonging, and empathy, we are helping children to develop the regulation skills needed to get along and live in a diverse society.

|

Pause to Reflect… Gender Sterotypes In American society, we have established and readily accept gender stereotypes. We have many biases about how boys and girls should look and behave. If you have grown up in America, you may be familiar with some of the following gender stereotypes: Only girls cry. Boys are stronger than girls. Boys are active and girls are passive. It’s ok for boys to be physically and emotionally aggressive after all they are just being boys. What other gender stereotypes have you heard? These stereotypes are so ingrained in us that we are often unconscious of how we perpetuate them. For example, we may compliment girls on their clothing and boys on their strength. We are called to look at our stereotypes/biases and find ways to counteract them when we are faced with the variety of ways in which boys and girls behave in our early childhood classrooms. How can we do that? We do that by engaging in dialogue with others to challenge our stereotypes and change our practices to create more inclusive and supportive environments. Note- This is an example of only one of the identity categories that is mentioned above. Think about what other stereotypes you have about the other categories of identity listed above. What can you do to challenge your assumptions/biases to help you in becoming an early childhood professional who engages in inclusive and supportive practices? |

Attachment

“Attachment is the tendency of human infants and animals to become emotionally close to certain individuals and to be calm and soothed while in their presence. Human infants develop strong emotional bonds with a caregiver, particularly a parent, and attachment to their caregivers is a step toward establishing a feeling of security in the world. When fearful or anxious the infant is comforted by contact with their object. For humans, attachment also involves and affects the tendency in adulthood to seek emotionally supportive relationships.” xvi

As noted in Attachment Theory, co-created by Bowlby and Ainsworth, it is clear to us that attachment is a critical component of healthy development. Our brains are wired for attachment. Many of you may have witnessed a newborn baby as they interact with their parents/caregivers. Their very survival hinges on the attachment bonds that develop as they grow and develop. Children who are not given the proper support for attachment to occur may develop reactive attachment disorder. Reactive attachment disorder is a rare but serious condition in which an infant or young child does not establish healthy attachments with parents or caregivers. Reactive attachment disorder may develop if the child’s basic needs for comfort, affection, and nurturing are not met and loving, caring, and stable attachments with others are not established. xvii

Why is this important for early childhood practitioners to know? The role of an early childhood professional is one of caregiving. While you are not the parent, nor a substitute for the parent, you do provide care for children in the absence of their parent. Families bring their children to early childhood centers for a whole host of reasons, but one thing that they share is that they trust their child’s caregivers to meet the need of their child in a loving and supportive way.

Healthy attachments begin with a bond with the child’s primary caregivers (usually their family) and then extend to others who provide care for their child. How we as early childhood professionals care and support children, either adds or detracts from their healthy attachment. Our primary role is to ensure that the needs of children are met with love and support.

It is also possible that children may enter our early childhood environment with unhealthy attachment or could possibly have reactive attachment disorder. In this case, it is our ethical and moral responsibility to meet with the family (in Chapter 8 – Partnering with Families more context and content will be given to support this statement) and to provide them with resources and support that they could use to help their children to have better outcomes. As the course of study of an early childhood professional, affords them with knowledge and understanding of how children grow and develop, families do not often have this foundational knowledge. It is our duty to develop a reciprocal relationship with families that is respectful and compassionate. When we offer them support, we do so without judgment.

The Value of Play in Childhood

There has been much research done in recent years about the importance of play for young children. During the last 20 years, we have seen a decline in valuable play practices for children from birth to age 8. This decline has been shown to be detrimental to the healthy development of young children as play is the vehicle in which they learn about and discover the world.

|

Quotable “Play is a legitimate right of childhood, representing a crucial aspect of children’s physical, intellectual, and social development.”xviii

|

The true sense of play is that it is spontaneous, rewarding, and fun. It has numerous benefits for young children as well as throughout their lifespan.

It helps children build foundational skills for learning to read, write and do math.

It helps children learn to navigate their social world. How to socialize with peers, how to understand others, how to communicate and negotiate with others, and how to identify who they are and what they like.

It encourages children to learn, to imagine, to categorize, to be curious, to solve problems, and to love learning.

It gives children opportunities to express what is troubling them in their daily life, including the stresses that exist within their homes and other stresses that arise for them outside of the home.

If you remember from the history chapter (Chapter 1), Fredrich Froebel introduced the concept of Kindergarten which literally means “child’s garden.” If you recall, the focus of the kindergarten that Froebel envisioned, focused on the whole child rather than specific subjects. The primary idea is that children should first develop social, emotional, motor, and cognitive skills in order to transform that learning to be ready for the demands of primary school (Chapter 6 – Early Childhood Programming will provide more detail about this). Play is the primary way in which children learn and grow in the early years.

A teacher who understands the importance and value of play organizes the early childhood environment with meaningful activities and learning opportunities (aka Curriculum) to support the children in their classroom. This means that the collective and individuality of the children are taken into consideration as well as their social and cultural contexts (DAP).

Here are some things to consider in thinking about play:

Play is relatively free of rules and is child-directed.

Play is carried out as if it is real life. (As it is real life for the child)

Play focuses on being, rather than doing or the end result. (It is a process, not a product)

Play requires the interaction and involvement of the children and the support, either direct or indirect, of the early childhood professional.

Throughout the early years of development (0 -8), young children engage in many different forms of play. Those forms of play include but are not limited to: xix

Symbolic Play – play that provides children with opportunities to make sense of the things that they see (for example, using a piece of wood to symbolize a person or an object)

Rough and Tumble Play – this is more about contact and less about fighting, it is about touching, tickling, gauging relative strength, discovering flexibility, and the exhilaration of display, it releases energy and it allows children to participate in physical contact without resulting in someone getting hurt

Socio-Dramatic Play – playing house, going to the store, being a mother, father, etc., it is the enactment of the roles in which they see around them and their interpretation of those roles, it’s an opportunity for adults to witness how children internalize their experiences

Social Play – this is play in which the rules and criteria for social engagement and interaction can be revealed, explored, and amended

Creative Play – play which allows new responses, the transformation of information awareness of new connections with an element of surprise, allows children to use and try out their imagination

Communication Play – using words, gestures, charades, jokes, play-acting, singing, whispering, exploring the various ways in which we communicate as humans

Locomotor Play – movement in any or every direction (for example, chase, tag, hide and seek, tree climbing)

Deep Play – it allows children to encounter risky or even potentially life-threatening experiences, to develop survival skills, and conquer fear (for example, balancing on a high beam, roller skating, high jump, riding a bike)

Fantasy Play – the type of play allows the child to let their imagination run wild, to arrange the world in the child’s way, a way that is unlikely to occur (for example, play at being a pilot and flying around the world), pretending to be various characters/people, be wherever and whatever they want to be and do

Object Play – use of hand-eye manipulations and movements

Communicating with families about the power and importance of play is necessary but can be tricky. In an article entitled, “10 Things Every Parent Should Know About Play” by Laurel Bongiorno published by NAEYC (found on naeyc.org), this is what she states: xx

Children learn through play

Play is healthy

Play reduces stress

Play is more than meets the eye

Make time for play

Play and learning go hand-in-hand

Play outside

There’s a lot to learn about play

Trust your own playful instincts

Play is a child’s context for learning

As you continue your studies in early childhood education, you will begin to form and inform your own ideas about the value of play as you review the literature and research that has been compiled on this subject.

IN CLOSING

This chapter explored the developmental and learning theories that guide our practices with young children. This included a look at some of the classic theories that have stood the test of time, as well as the current developmental topics to give us opportunities to think about what we can do to create the most supportive learning environment for children and their families. Learning is a complex process that involves the whole child – physically, cognitively, and affectively.

As we build upon the previous knowledge of Chapter 1 and Chapter 2, Chapter 3 will provide information on the importance of observation and assessment of children in early learning environments. Hopefully, you will note that, while this course looks at the foundational knowledge and skills you need to be an effective early childhood professional, what you are learning is deeply interwoven and connected.

|

Pause to Reflect… Theory Takeaway What was the most important information that you learned from this chapter on theory and key developmental topics? Why was it most important to you and how do you plan to incorporate that information in your practices with young children and their families? When we think about what we are learning metacognitively (thinking about thinking), it helps us to make sense of that knowledge and reflect on how it pertains to us. This is a practice that will suit you well in your journey as an early childhood professional. |

A general statement that describes the desired knowledge, skills, and behaviors of a student graduating from a program.

Competencies commonly define the applied skills and knowledge that enable people to successfully perform in professional, educational, and other life contexts.