Magnolia Jiminez, Rachel Otero, and Blessed Sampa

Introduction

This chapter focuses on notable issues in healthcare in the United States and provides a solution policy to combat these issues. An overview of healthcare in the United States, its history, and the impact of the Affordable Care Act is given. This is followed by a discussion of Healthcare inequality and investigation into the coverage disparities and barriers to access in healthcare. The outbreak of COVID-19 brought attention to and worsened the aforementioned issues disproportionately affecting certain demographics and socioeconomic groups. The impacts and an investigation into these disparities are included in this chapter.

2.1 Health Care in the United States

2.1.1 History and Overview

This section of the chapter focuses on healthcare coverage in the United States. First, we believe it’s important to understand the history of healthcare in the United States. The United States started to adopt public assistance that aimed at women and children during the 1940s. However, an expansion for national health insurance was far from becoming a reality at the time. The health of the poor started to become a shared concern that was seen as an issue of low “national vitality.” Moreover, by the beginning of the 20th century, one-third of workers in the United States were insured against loss of earnings due to sickness. This insurance was a result of the organized trade unions. Only a few of these trade unions provided medical care to the workers (Glennerster, H., & Lieberman, R. C., 2011).

The United States was influenced by some of the actions in regards to healthcare insurance that the United Kingdom took. Under David Lloyd George in 1911, the United Kingdom’s insurance model was extended to cover the costs of primary care of insured workers. David Lloyd George was not necessarily interested in the health of its employees, Lloyd was more interested in the faster recovery of workers when they were sick, so they can return to work faster. The sooner workers return to work, the more money the company saves. This event led to the United States’ interest in healthcare. The next year, this idea was brought to the American Association for Labor Legislation and led to the creation of a committee to write a model bill for mandatory health insurance. Fast-forwarding to the postwar years in the United States, when a path for healthcare starts taking place. The Roosevelt administration had started to look at the inclusion of health insurance, along with old-age pensions, public assistance, and unemployment insurance, to the Social Security Act of 1935. However, the Roosevelt administration abandoned the idea upon the fear that political opposition might lead to the collapse of the legislation. Nevertheless, during the war, Roosevelt picked up on his ideals of health insurance, among other rights (Glennerster, H., & Lieberman, R. C., 2011).

Before the United States entered the war, Roosevelt and Winston Churchill set common aims and principles during a meeting held in Newfoundland in August 1941. This is what became known as the Atlantic Charter. Roosevelt and Churchill announced their commitment to “the fullest collaboration between all nations in the economic field with the object of securing, for all improved labor standards, economic advancement and social security.” Moreover, this vision was mostly focused on war objectives, but it was the vision that would aid in shaping the postwar world for which the Allies would stand for, and also is significant to what later on (Marshall 1964) would call social citizenship. Even though Roosevelt did not live to see his plan come to life, his successor, Harry Truman, carried out the plan, thus with little success. The next largest effort to expand the reach of U.S. social capital policy was the Employment Act of 1946 (Glennerster, H., & Lieberman, R. C., 2011).

An attempt to establish healthcare coverage in the United States includes the National insurance proposal, carried out by Senators Robert Wagner of New York and James Murray of Montana, and Representative John Dingell of Michigan. Wagner and Montana introduced to legislation the idea to create a comprehensive system of social insurance that includes universal health insurance, which was later on followed by the Social Security model. At the time, Harry Truman accepted the proposal, but a conservative in Congress prevented the proposal from becoming a major social form. In 1948, the reelection of Harry Truman paved the way for health insurance in the United States. The restoration of Democratic majorities in the House and the Senate helped Truman implement his health insurance ideals. However, attempts to implement national healthcare were dismissed once again due to the Cold War with the Soviet Union that became a “shooting start.” Furthermore, during the Cold War, Republicans, with support from AMA, were able to attack the health insurance proposal labeling it a “socialized medicine.” This phrase promoted the growing anxiety in American politics and culture about the potential influence of socialism in America that began taking hold during the New Deal years. Ultimately, National Health insurance did not come into law till later (Glennerster, H., & Lieberman, R. C., 2011).

In 1980, interest to challenge the public service monopolies and trade unions powered by the introduction of competition for state funding was what led to one of the ideas that were enforced for health care through an organization referred to as “health maintenance organizations” (HMOs). HMOs proved to grow in the United States in the years from the mid-1980s through the mid-1990s along with its promise to reduce health care costs. Overall, this section showed some of the events that led to the formation of healthcare coverage in the United States. The next section of the chapter focuses on the next law that made healthcare insurance more affordable and accessible to a significant number of Americans in the United States (Glennerster, H., & Lieberman, R. C., 2011).

2.1.2 Healthcare coverage under the Affordable Care Act

Affordable Care Act, making healthcare affordable for Americans. This section of the chapter specifically focuses on the economic perspective on the Affordable Care Act, its expectations, and reality. Information regarding an economic perspective is gathered from article research from Vanderbilt and Boston Universities. The Affordable Cares Act (ACA) came into effect in 2010 intending to mitigate both high uninsured rates and rising healthcare spending. This would be accomplished by expanding insurance reforms and efforts to reduce waste. When the passage was created, ACA was expected to have positive impacts on the economy. US households’ spending on premiums and out-of-pocket payments should’ve decreased, thus providing households with a sense of financial security, improved job mobility, and improved health (Nikpay, S., Pungarcher, I., & Frakt, A., 2020).

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) expected the ACA’s reform to increase coverage by 32 million Americans by 2019. The goal of this reform was to strengthen financial security by protecting disastrous health spending while decreasing out-of-pocket expenses. Moreover, through the improvement of the quality and affordability of other options to employer-sponsored insurance (ESI), the ACA’s earnings were also anticipated to lessen the “job lock.” The “job lock” was when employees were disheartened from quitting their jobs because they worried about losing their healthcare coverage or paying more for it. In 2014, it was estimated by the CBO that the ACA would motivate 2.5 million Americans to exit the labor force by 2023, likely due to retirement or becoming self-employed. Furthermore, the second goal of the ACA was to decrease the country’s health spending growth rate. The enacted law intended to decrease healthcare spending by performing the following: increased competition among insurance companies, decreased federal tax subsidies for ESI plans, and in the form of Medicare and Medicaid payment reforms and reimbursement cuts. The purpose of the reimbursement cuts was mostly directed to hospitals and Medicare Advantage plans, reductions in the rapidly increasing rates of payments to providers, “delivery system reforms” (DSRs) (Nikpay, S., Pungarcher, I., & Frakt, A., 2020).

It was estimated that the CBO would lower federal deficits by $198 billion. Cost-control provisions would lower federal spending by roughly $416 million over 10 years, in relation to the current numbers (Cutler, Davis, and Stremikis 2010). Economists anticipated that numerous of these mainly “federally cost-control measures” would have spillover effects on the spending of private healthcare (Nikpay, S., Pungarcher, I., & Frakt, A., 2020). For this reason, some economists indicated that reforms of this kind to the ACA could decrease the national spending by $590 billion over 10 years in relation to the estimated total national healthcare spending over the same 10 years period without the ACA (Cutler, Davis, and Stremikis, 2010).

Furthermore, some of the realized economic effects of the ACA are the following. When it comes to coverage, between the years 2009 and 2018, the uninsured rate fell from 15.1% to 8.9%. The largest decrease occurred after the implementation of the ACA’s coverage provisions. This demonstrates that the adjustments to the ACA helped provide healthcare insurance to significantly a lot more people in the United States. Between the years of 2013 and 2014, the uninsured rate decreased from 13.3% of Americans, 41.8 million, in 2013, to 7.9% of Americans, 25.6 million, in 2014. Overall, American individuals with coverage in the individual market increased from 11.4%, 35.8 million, to 14.1%, 41.1 million. The enrollment on Medicaid increased from 17.5%, 54. 9 million, to 19.5%, 61.7 million (Smith and Medalia 2015). It’s important to highlight that these people wouldn’t have had access to healthcare if it wasn’t because of the ACA. The premium for the average plan increased moderately by 9% between 2009 and 2014 after the ACA took effect (Adler and Ginsburg 2016). Additionally, people in Medicaid expansion states are 1) 11% less likely to have to pay out-of-pocket medical or premium expenditures (Abramowitz 2020), 2) 11% less likely to use payday loans (Allen et al. 2017), 3) 2.8% less likely to file for bankruptcy (Caswell and Waidmann 2019), and better improvement in their credit scores (Brevoort, Grodzicki, and Hackmann 2017). This evidence shows that ACA removed a financial burden to those who were able to access healthcare coverage under the ACA (Nikpay, S., Pungarcher, I., & Frakt, A., 2020).

Visits to the primary doctor also increased by 24.1% (Biener, Zuvekas, and Hill 2018), prescription drug use increased by 19% (Ghosh, Simon, and Sommers 2019), and the use of specific high-value medical screenings by 9.9–11.6% (Sommers et al. 2017; Guth et al. 2020). Moreover, data shows that the ACA caused an improvement in health among Americans. Two recent studies showed that mortality decreased. Specifically, Miller and colleagues (2019), linked mortality and survey data on Americans who were targeted by the ACA Medicaid expansion. From this survey, the authors found that the Medicaid expansion prevented 19,200 deaths during its first four years. This data is significant because it reveals how vital healthcare coverage is in the United States, where before the ACA, many people’s lives were at risk. Nevertheless, there are still many challenges that the United States faces and still needs improvement to overcome. The next section of the chapter focuses on the healthcare inequality that exists in the United States, along with comparisons and evaluation of different demographics and their accessibility to healthcare coverage (Nikpay, S., Pungarcher, I., & Frakt, A., 2020).

2.2 US Health Care Inequality

Healthcare inequality arises when there are unfair, systematic differences in healthcare access between different groups of people in an economy. These systematic differences are avoidable and unjust. Inequality in healthcare occurs across different dimensions, including race or ethnicity, socioeconomic status, age, location, gender, disability status, and sexual orientation. Healthcare inequality leads to poor quality of healthcare, worse health consequences for minority racial/ethnic groups and people with low socioeconomic status, increased direct and indirect healthcare expenses, lower productivity, and overall contrasting use of shared healthcare monies (ASTHO, 2019). Lack of access to healthcare results in a huge number of deaths every year. Studies show that more than 130,000 Americans died between 2005 and 2010 and approximately between 20,000 and 45,000 Americans die each year due to a lack of health insurance (Cecere, 2009). Approximately one in five adults under age 65 and nearly one in ten children are uninsured and there is a 40% increase in the risk of death among those that do not have insurance (Cecere, 2009).

Health inequalities involve differences in health status, for example, life expectancy and commonness of health conditions, healthcare access like availability of treatments, quality, and experience of care, for example, levels of patient satisfaction, behavioral risks to health, for example, smoking rates, wider determinants of health, for example, quality of housing (Williams et al., 2020). There are also interactions between the factors. For example, groups with particular protected characteristics can experience health inequalities over and above the general and pervasive relationship between socio-economic status and health (Williams et al., 2020).

2.2.1 Cost of Healthcare and Barriers to Access

Low income seems to be the biggest barrier to healthcare access. High cost of healthcare results in people having little to no access to healthcare. The cost of healthcare in the United States is very high because health insurance is privatized. The United States spent approximately $3.6 trillion on healthcare in 2018 and they keep increasing each year (Peterson, 2020). A huge part of this amount is paid for by residents out of pocket. Those that cannot afford to pay for health insurance have very little access to good healthcare resources. Without health insurance, the healthcare costs burden is higher on individuals since they have to pay for them out of pocket. This will prevent a lot of uninsured people from accessing healthcare.

Another factor that prevents people from accessing healthcare is the lack of availability of services. In poor neighborhoods, they have poor healthcare resources. As a result, people would rather self-medicate, and they also lose trust in the healthcare providers. Therefore, they will seek medical assistance. Also, when there is poor availability of healthcare resources, there will be delays in receiving appropriate healthcare, people are not able to get preventive health services such as immunizations, there is poor management of chronic diseases, and the financial burden will keep increasing.

2.2.2 Comparison of Demographics With and Without Health Care Coverage/ Access

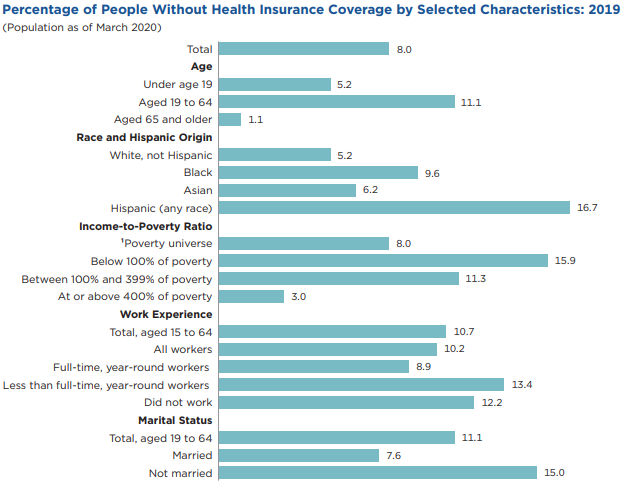

There are disparities in healthcare access among different demographics in the U.S. Race or ethnicity, disability, geographic location, income levels, work experience, marital status, sex, and age are all different demographics that have different accesses to healthcare. The graph below was obtained from the United States Census Bureau and it shows the percentage of people without healthcare coverage by different characteristics.

According to economists and health experts, people who live in poor neighborhoods live shorter lives (Inequality.org, 2020). Income inequality is one of the biggest determinants of healthcare access. People who live in poor neighborhoods are normally at the bottom of the income bracket. Therefore, there are traits associated with lower income. For example, their living conditions affect their health. There is poor access to clean water and good heating systems, their environment is not clean or well sanitized, and they do not eat healthily. All of these factors affect their health. On top of all of these poor living conditions, they have poor access to healthcare most because a lot of them are uninsured due to lower-income. As a result, very few people visit the doctor for yearly checkups and a lot of them will not know of a serious health condition until it’s too late. In the 1970s, there were not a lot of differences in the death rates between cancer patients in poor and rich areas. However, that changed over the years. The American Cancer Society data shows that rich counties have significantly lower cancer death than poor counties (Inequality.org, 2020). Lung cancer deaths in low-income counties have increased, from 41.2 per 100,000 per year to 47.7, while decreased a little in the higher-income counties (Inequality.org, 2020).

The United States is one of the countries that have high levels of income inequality. The World Health Organization states that people live longer in nations where there are lower levels of inequality (Inequality.org, 2020). Income inequality is one of the biggest causes of healthcare inequality in the US. The life expectancy of the wealthiest Americans now exceeds that of the poorest by 10–15 years (Kaestner & Darren Lubotsky, 2016). The US is one of the countries that rely on private health insurance. This makes the healthcare system in the US by far the most expensive in the world (Dickman, Himmelstein, & Woolhandler, 2017). As a result, a lot of people from low-income households cannot afford to pay for these private health insurance plans suffer since they are pricey. Therefore, they can barely pay for treatment and they are the most affected by this system. Before the implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), about 17% of the population was uninsured, and even after the law’s implementation 8.8% remained uncovered as of early 2017 (Dickman, Himmelstein, & Woolhandler, 2017). Before the ACA, 39% of Americans with low income reported not seeing a doctor for a medical problem because of the high cost, compared with 7% of low-income Canadians and 1% of those in the UK (Dickman, Himmelstein, & Woolhandler, 2017).

In the US, there is also a disparity in healthcare coverage between different races. For racial and ethnic minorities in the United States, health disparities take on many forms, including higher rates of chronic disease and premature death compared to the rates among whites. There is evidence that shows that healthcare is worse for racial and ethnic minorities (Dickman, Himmelstein, & Woolhandler, 2017). African Americans have a higher risk of getting heart disease, stroke, diabetes, influenza, etc. as compared to their white counterparts (Health Disparities Among African-Americans | Pfizer, 2020). In 2017, 89% of African Americans had health care coverage compared to 93% of white Americans; 44% of African Americans had government health insurance that year (Health Disparities Among African-Americans | Pfizer, 2020). Also, 12% of African Americans under the age of 65 reported having no health care coverage that year.

There is a difference in infant mortality between different ethnic and racial groups. According to the National Center for Health Statistics, there has been a decrease in the national infant mortality rate. However, there are still some disparities between different racial and ethnic groups (NCHS, 2016). Children born in African American homes had the highest infant mortality rate of about 11.11 infant deaths per 1000 births in 2013 and the lowest in Asian homes with an infant mortality rate of 3.9 infant deaths per 1000 births (NCHS, 2016).

Gender inequality is one of the determinants of healthcare inequality. There have been gaps in education attainment, pay rates, and employment between men and women. Gender disparities in health and healthcare access have been going on for a long time. Because the quality of healthcare is mostly determined by income levels, the gender wage gap plays a major role in the disparities in healthcare access. Since women earn less than men, there is a possibility that men will have better access to healthcare than women.

2.2.3 Evaluations of Demographics

Low-income neighborhoods do not have access to good hospitals and medical facilities. This is because these service providers do not make a lot of money in these areas. Also, due to the levels of poverty in these neighborhoods, there are high crime rates. As a result, most of these neighborhoods have been neglected since it is not good for business. Therefore, the only services available are those provided by the government. In most cases, these areas are poorly maintained, there are shortages of both medication and medical professionals.

One’s economic resources can determine the availability and quality of food, housing, medical care, and other necessities. Many poor people do not qualify for Medicaid. Many of them work very low-income jobs that do not provide medical insurance and are making minimum wage. Their earnings are barely enough to cover health care costs and even with some assistance, it is insufficient especially in very poor neighborhoods. Studies have shown that income and education levels play a major role in people’s health. Those at the bottom are the poor and least educated have the worst health experience than those with higher income levels and more education. People who are educated or those with a college degree earn significantly higher than high school graduates. Their jobs are most likely to have a better benefits package which includes health insurance. With their earnings, they can also afford to eat better and healthier. They have better access to healthcare because they can put more money toward their coverage.

One way racial segregation affects health status is related to the quality of food available in different neighborhoods (Yearby, 2018). Poor neighborhoods seem to have limited access to food and very limited healthy food choices. This increases the risk factor for cancer, might result in obesity, and heart disease (Yearby, 2018). Residents do not have access to healthy food due to a lack of supermarkets and a majority of convenience stores and fast-food restaurants as the primary food outlets (Yearby, 2018). In a lot of cases, racial minority groups are found in these neighborhoods. Therefore, they are the most affected.

Racial segregation also affects where African Americans receive care (Yearby, 2018). In racially segregated neighborhoods, African Americans are disproportionately likely to go through surgery in low-quality hospitals, whereas in areas with low degrees of racial segregation, African Americans and Caucasians are likely to undergo surgery at low-quality hospitals at the same rate (Yearby, 2018). These disparities are not a result of individual or group behavior but decades of systematic inequality in American economic, housing, and health care systems.

The socioeconomic differences within different racial or ethnic groups affect how much healthcare each group receives. Studies have shown that when both race and socioeconomic levels were taken into account when it comes to infant mortality and adult life expectancy, blacks have worse outcomes than whites at each income and education level (Yearby, 2018). Blacks may experience different health benefits at a given income level than whites. This could be as a result of different socioeconomic backgrounds between blacks and whites, more blacks living in disadvantaged communities, or this could be a result of racial biases that cannot be measured (Yearby, 2018).

2.3 Effects of COVID-19 on Healthcare

2.3.1 Healthcare Expenditure, Price & Utilization

Following the outbreak of Covid-19, the aforementioned issues only worsened while continuing to disproportionately affect lower-income and Black and Hispanic individuals. In this section, we give an overview of the effects of covid-19 on the health care system in the US such as healthcare spending, utilization, cost, and coverage. In addition to this, disparities in different demographic groups in the US, and mortality rates brought about by Covid-19 are discussed. Building on the work of Corwin Rhyan, Ani Turner & George Miller where healthcare spending, price, and usage since the start of the pandemic in the US are examined. The price data of healthcare spending from The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) is used and is broken out by payer. These players include entities such as Medicare, Medicaid, private health insurance, and more. The data from this study is used to estimate the underlying trends in price growth in the same time period as the start of the Covid-19 pandemic in efforts to identify some of the market and government trends that are driven by price growth in the health sector.

Additionally, HSEI reports are used to combine data on overall health sector spending and prices to estimate the underlying trends in health care utilization. In this study, Utilization was calculated as the residual of health sector spending growth and health sector price growth each month. This approach includes an HSEI measure of utilization for direct changes in utilization, such as the number of office and hospital visits in a period or the number of prescriptions filled in a period. As well as, for changes in the intensity of services provided. Including the number of individual services or procedures provided per visit (2020).

According to Rhyan et al., The impact that covid has had on health care prices actually appears to be subtle. However, there is a much less subtle effect of lower health care utilization. The decrease in utilization includes things such as the absence of elective care, a decrease in many types of in-person visits, and the temporary closing of many outpatient offices. These factors combined shrank the amount of health care spending. Yet, the average prices paid for remaining health care services appear to have only changed slightly. The HCPI year-over-year growth has been between 1 and 3% since late 2017. Excluding a slight rise from February 2020 which remains in a range that is expected given historical trends. Moreover, In this period the economy-wide price growth, measured by using the GDP Deflator (GDPD) has slowed while remaining positive. Leading to a larger gap between health care price growth and economy-wide inflation (2020).

Overall, these are notable figures, given that the price growth in health care since 2011 has been at or below the level of the US’s overall inflation. In the most recent period available in August 2020, at the time of this study’s writing, HCPI grew at a year-over-year rate of 2.7%. Contrasting with a GDP deflator value of 0.9%.

Out of the different health sector categories, year-over-year price growth at the bottom of the 2020 pandemic-induced recession was the largest in nursing home care (4.2%). Followed by dental care (3.1%), home health care (2.7%), and hospital services (2.6%). Year-over-year price growth for prescription drugs (1.1%) and physician services (0.8%) were more moderate, especially when compared to other price growth such as the price growth observed during the Great Recession, measured as of June 2009. (Rhyan et al., 2020).

The drop in health care services or reductions in the volume of care could likely be a result of the drop in the demand for services. This drop in demand would likely be due to the perceived risk of Covid-19 infection and delaying elective health procedures. In this case, one may expect to observe a decline in health sector prices. However, this has not yet been observed and is likely due to the unique characteristics in the healthcare market including its unique way in which prices are set. Furthermore, the drops in utilization could also be due to the decrease in the supply of services. In many states across the US, there have been forced pauses in elective care in order to free up space for Covid-19 patients in hospitals. Also to decrease the risk of infection in healthcare settings (Rhyan et al., 2020).

Overall, the impacts measured resulting from covid-19 and its accompanying recession are present and definitely exacerbated the aforementioned issues yet it has also bounced back to an extent. However, healthcare spending has not fully recovered as of the final quarter of 2020. Throughout the same period, healthcare prices have continued to rise and began outpacing economy-wide price growth by a larger margin. Covid-19 and its accompanying recession display a rare interruption in the growth in health care spending that has been relentless for decades. At a minimum, it has likely reset to a level lower than what would have been, absent the pandemic. Any extent to which these reductions are good or bad for our health and economy will be a major part of the U.S. health services research agenda. (Rhyan et al., 2020 )

2.3.2 Racial, Ethnic and Socioeconomic Disparities

As of June 2020, COVID-19 had resulted in over 2.3 million confirmed infections in 121 thousand facilities in the USA. Within this statistic, when separated by race and ethnicity there are stark differences in incidence (Benitez et al., 2020). Building on the findings of Joseph Benitez, Charles Courtemanche & Aaron Yelowitz as they examine the racial and ethnic disparities in confirmed COVID-19 cases across six diverse cities. Atlanta, Baltimore, Chicago, New York City, San Diego, and St. Louis.

Their analysis links the COVID-19 outcomes to six separate data sources to control for ZIP code level demographics. These demographics include housing, socioeconomic status, occupational choices, transportation modes, health care access, long-run opportunity (income mobility and incarceration rates), human mobility, and population health disparities.

Statistically significant results were found with economically meaningful disparities for both Black and Hispanic individuals at the ZIP code level in confirmed cases. Additionally, the majority of the disparity remains unexplained after including extensive controls. Without additional covariates, a 10% increase in a ZIP code’s share of Black residents is associated with 9.2 additional confirmed COVID-19 cases per 10,000 residents. A similar change was observed with the Hispanic share being associated with 20.6 additional cases. Both of these figures are sizable changes relative to the average quantity of confirmed case rate, 153 per 10,000. (Benitez et al., 2020)

The primary outcome variable was confirmed COVID-19 cases per 10,000 population. Serological surveys provided strong evidence that confirmed cases are actually an undercount of total infections. However, confirmed case numbers still have clear clinical and economic significance. When weighted by population, the median ZIP code had 143 cumulative cases per 10,000 population by early June and a cumulative infection rate measured at about 1.4%. The measured infection rates varied substantially, with 12 cases per 10,000 (0.1%) in the lowest decile and 315 cases per 10,000 (3.2%) in the highest decile. On the national level, the fatality and hospitalization rates for confirmed cases were roughly 5% and 10%, respectively, by June of 2020. When comparing this by city, New York City had the highest rate of confirmed cases (2.3%), following by Chicago (1.7%) and Baltimore (0.9%). The other three groups had confirmed case rates varying from 0.26 to 0.48%. In the aggregate, there were more than 271,000 confirmed COVID-19 cases in these 6 cities. Which was approximately 14% of all cases nationally at that point (Benitez et al., 2020).

In the analysis, other covariates are included. For example, the demographics add six additional variables for percent male, percent foreign, and percent in each of four age bins to the specification. Across the remaining factors, the disparity measured seems to remain significant regardless of the set of controls that are included shows disparities that are roughly 60% as large as the column of data which includes only the race/ethnicity variables, city fixed effects, and a constant term which shows a key insight. More than half of the overall disparity in confirmed COVID-19 cases remains unexplained even with extensive control sets that should plausibly affect the transmission of the virus (Benitez et al., 2020).

With a focus on ZIP codes in Chicago and New York, these localities were able to provide additional data on COVID-19. The initial overall disparities are larger in the data which includes only the race/ethnicity variables, city fixed effects, and a constant term. With a 10% point increase in a ZIP code’s Black share is associated with 12.4 additional confirmed COVID-19 cases per 10,000. However a similar change in the Hispanic share is associated with 24.8 additional COVID-19 cases. Both are significant relative to the average quantity of confirmed cases of 219 per 10,000 for the two cities. When neighborhood characteristics are added in the remaining data columns, in some instances, the observed disparity falls and rises in others. The full set of controls remains sizable disparities for both Blacks and Hispanic individuals, and again more than half of the overall disparity remains unexplained (Benitez et al., 2020).

Yet, any observational analysis identifies correlations, not causation (Knittel and Ozaltun 2020). Some tempting yet not causational neighborhood factors including some that may represent the increased likelihood of transmission. Including factors such as density, occupation, transportation mode, or health care access. These variables could affect each other or be influenced by unobservable characteristics of the ZIP code, being one of the reasons preventing observations from being causal.

When examining the COVID-19 fatalities in Chicago and New York at the ZIP code level. In order to maintain comparability, COVID-19 fatalities are scaled by millions to investigate The extent to which variation in fatalities is simply explained by greater numbers of confirmed COVID-19 cases, or how factors apart from additional cases hold significance. The results showed that the coefficients fall by 50–100%. This suggests the racial and ethnic disparities in infection spreading are a crucial determinant of the resulting fatalities. For the Hispanic proportion, the coefficient estimate is close to zero and Black proportion the estimate is roughly half as large. In other data columns, additional covariates similar to the ones in this section are added; however, with sufficient controls, the original disparities show to be insignificant.

Overall, a 10 % increase in a ZIP code’s Black share is associated with 12.4 additional confirmed COVID-19 cases per 10,000 population. A similar change in Hispanic share is associated with an additional 24.8 COVID-19 cases. Again, both of these figures are meaningful and sizable changes relative to the quantity of average confirmed cases rate. 219 per 10,000 population for these two cities. When neighborhood characteristics are added in the remaining columns in some instances the disparity falls, and in others, it rises. Additionally, there remains sizable disparities for both Black and Hispanic individuals with the full set of controls, with more than half of the overall disparity remaining unexplained (Benitez et al., 2020). Even though some racial and ethnic disparities are attributed to various socioeconomic risk factors, most of the case disparities remain unexplained. The pandemic’s key risk factors are unevenly distributed across communities and the unexplained disparities are a largely considerable example of the difficulty in addressing deeply embedded racial and ethnic inequalities in healthcare and outcomes. Even though more study is needed, it suggests that the policy enacted in efforts to slow COVID-19’s spread should have considered the barriers to improvement across different groups including minorities. Policy such as Economic stimulus or expanding health insurance coverage is not likely to be fully adequate with the complexity and inequality embedded in healthcare outcomes (Benitez et al., 2020).

2.3.3 Mortality Rates of Minorities

According to Jung, Manley, and Shrestha evidently higher mortality rates for Black and African American Individuals as well as other minority groups resulting from COVID-19. In their study, they investigate the possible cause of this phenomenon by seeking the socioeconomic roots of the racial disparities found in COVID-19 mortality. This is done by using county-level mortality, economic, and demographic data from 3,140 counties (2021). For the purpose of this chapter, we will focus only on African American/ Black and Hispanic/Latino Individuals.

When controlling for state-level effects, there is a strong positive correlation across counties between the minority’s population share and COVID-19 deaths. In the case of For Hispanic/Latino minorities, the correlations are fragile. As they disappear mostly once corrected for education, occupation, and commuting patterns. Contrastingly, African Americans/ Black populations’ correlations are quite robust. Consequently, the disparity, large portions of which are not explained by these aforementioned socioeconomic factors. Other socioeconomic factors unfortunately which are beyond the scope of Jung, Manley, & Shrestha’s study may have been able to provide more insight.

These other factors, listed in Centers for Disease Control include, The Concentration of workers in essential services, the Differential incidence of pre-existing conditions that can make a COVID-19 infection more dangerous. Differential availability of paid sick leave, Residential segregation, Discrimination in healthcare services (implicit racial or ethnic bias in healthcare providers and find some effect on healthcare outcomes) and, “Weathering,” defined by Chowkwanyun and Reed (2020) as the “advanced aging caused by bodily wear and tear from fight-or-flight responses to external stressors, especially racial discrimination (Jung, Manley, & Shrestha, 2021).

As an example, when broken down by race and age group, the figures released by the government of New York City, the ratio of deaths per million for African-American or Hispanic/Latino individuals relative to white individuals varies from 1.58 to 5.95. Additionally, relative mortality ratios that are reported age-corrected by state, in which data is broken up by race, show a range from a ratio of 18 for the African-American- to White ratio in Wisconsin to 0.44 for Pennsylvania. The estimate for the overall US is a ratio of 3.57 for African American individuals relative to white individuals. With 1.88 for Hispanic/Latino individuals relative to white. In regards to the racial/ethnic disparities in health insurance in the US which are well-known. 5.4% of white, non-Hispanic Americans had no healthcare insurance in 2018, compared to 9.7% of Black Americans and 17.8% of Hispanic individuals (any race). (Jung, Manley, & Shrestha, 2021)

Overall, for Black and Hispanic/Latino individuals, there are strong positive correlations across counties between COVID-19 deaths and the population share of minorities. For Hispanic/Latino minorities these correlations are more fragile than for Black individuals, and largely disappear once they are corrected for occupation, education, and commuting patterns. However, for Black/African American individuals the correlations are very robust. Regardless of the factors controlled for, racial disparity in the mortality rates persist. Unexpectedly, this does not seem to be due to differences in income, occupational mix, poverty rates, education, nor access to healthcare insurance. Which have been hypothesized by many of being a possible key source or reason. A significant portion of this disparity can actually be traced to public transit use. This also helps to explain some of the larger differences in mortality observed between Los Angeles and New York City (Jung, Manley, & Shrestha, 2021).

2.4 Possible policy solutions to Inequality

One thing that can be done to reduce inequality in healthcare is putting more money into developing healthcare facilities and improving healthcare access in poor neighborhoods. There is a need to provide healthcare services at affordable costs so that those in the low-income groups can have access to good healthcare. Containing the cost of healthcare is important for the country’s long-term fiscal and economic well-being. Reducing the cost of healthcare is not just going to benefit the people, but the economy as well. The U.S. has one of the highest costs of healthcare systems in the world. Instead of privatizing healthcare insurance, the government should be able to have some control too. They should also be able to control the costs and make them affordable for the majority of the population.

There is a need to improve living conditions that result in poor health. Poor neighborhoods need improvement. As mentioned in this chapter, people in poor neighborhoods have bad living conditions and have limited access to healthy food choices. The government can increase the supply of healthy food in poor neighborhoods. In the chapter, a lot of factors that resulted in poor healthcare access among different groups were tied to lower-income. Income inequality was said to be one of the biggest contributors to healthcare inequity. The government can find ways to redistribute income so that those at the bottom can earn enough to afford healthcare.

Another issue that needs to be addressed is healthcare inequality among different racial and ethnic groups. Good healthcare access should not just be accessed by a certain group of people but there need to be equal opportunities among different racial groups. Programs like the Affordable Health Act will enable a lot of people especially minorities to have better access to healthcare.

Solving the problem of healthcare inequality is going to take a very long time and might never completely be solved. The government has been trying to provide affordable healthcare for a long time. They provided Medicare for people above the age of 65 and it was a public insurance program (Tikkanem, et.al, 2020). Today, Medicare covers about 18% of Americans. In 2010, the Affordable Health Care Act and Patient Protection (Tikkanem et.al, 2020). This enables the government to finance and control healthcare coverage (Tikkanem et.al, 2020). This resulted in approximately 20 million Americans getting insurance coverage reducing uninsured adults from 20% in 2010 to 12% in 2018 (Tikkanem et.al, 2020).

Bibliography

ASTHO. (2019). The Economic Case of Health Equity. ASTHO, 1-11.

Benitez, J., Courtemanche, C., & Yelowitz, A. (2020). Racial and ethnic disparities in Covid-19: Evidence from six large cities. Journal of Economics, Race, and Policy, 3(4), 243-261.

Dickman, S. L., Himmelstein, D. U., & Woolhandler, S. (2017). Inequality and Healthcare System in the U.S. The Lancet, 1-11.

Dorsey, J. D., Hill, P., Moran, N., Azzari, C. N., Reshadi, F., & Shanks, I. (2020). Leveraging the Existing US Healthcare Structure for Consumer Financial Well-Being: Barriers, Opportunities, and a Framework toward Future Research. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 54(1), 70–99. http://web.b.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.oswego.edu:2048/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=14&sid=f6dd3c0e-7c19-40f3-bfea-3d1b32ac97b0%40sessionmgr103

Health Disparities Among African-Americans | Pfizer. (2020, September 9). Pfizer.com. https://www.pfizer.com/news/hot-topics/health_disparities_among_african_americans

Inequality and Health – Inequality.org. (2012). Inequality.org. https://inequality.org/facts/inequality-and-health/

Jung, J., Manley, J., & Shrestha, V. (2021). Coronavirus infections and deaths by poverty status: The effects of social distancing. Journal of economic behavior & organization, 182, 311-330 doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2020.12.019

Kaestner, R., & Darren Lubotsky, R. (2016). Health Insurance and Income Inequality. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 1-27.

McLaren, J. (2020). Racial Disparity in COVID-19 Deaths: Seeking Economic Roots with Census data (No. w27407). National Bureau of Economics http://www.nber.org/papers/w27407

Nikpay, S., Pungarcher, I., & Frakt, A. (2020). An Economic Perspective on the Affordable Care Act: Expectations and Reality. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 45(5), 889–904.

Oliver, A., & Brown, L. D. (2012). A Consideration of User Financial Incentives to Address Health Inequalities. Journal of Health Politics, Policy, and Law, 37(2), 201–226. h

Percentage of People Without Health Insurance Coverage by Selected Characteristics. (n.d.). Retrieved April 26, 2021, from https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/visualizations/2020/demo/p60-271/figure2.pdf

Rhyan, C., Turner, A., & Miller, G. (2020). Tracking the U.S. Health Sector: The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Business Economics, 55(4), 267–278.

Rhyan, C., Turner, A., & Miller, G. (2020). Tracking the US health sector: the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Business Economics, 55(4), 267-278. Retrieved March 7, 2021, from

Williams, E., Buck, D., & Babalola, G. (2020, February 18). What Are Health inequalities? The King’s Fund; The King’s Fund. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/what-are-health-inequalities

Yearby, R. (2018). Racial Disparities in Health Status and Access to Healthcare: The Continuation of Inequality in the United States Due to Structural Racism. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 77(3–4), 1113–1152.

Yeo, Y. (2017). Healthcare Inequality Issues among Immigrant Elders after Neoliberal Welfare Reform: Empirical Findings from the United States. European Journal of Health Economics, 18(5), 547–565Yoruk, B. K. (2018). Health Insurance Coverage and Health Care Utilization: Evidence from the Affordable Care Act’s Dependent Coverage Mandate. Forum for Health Economics and Policy, 21(2), 1–24.

Zewde, N. (2020). The Individual Welfare Effects of the Affordable Care Act for Previously Uninsured Adults. International Journal of Health Economics and Management, 20(2), 121–143.