This chapter was originally published as Black, S., & Allen, J. D. (2019). Insights from educational Psychology Part 11: Learning strategies. The Reference Librarian, 60(4), 288–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763877.2019.1626317. Minor modifications have been made to the version published in Reference Librarian.

Educational psychologists have conducted extensive research on which learning strategies are most effective. Most studies focus on test taking, and are thus not obviously applicable to librarians’ support of student learning. However, enough of the research is relevant to resource-based learning to justify a chapter on learning strategies in this book on insights from educational psychology for academic librarianship. This chapter presents evidence on how students tend to approach learning, summarizes the main findings on what learning strategies are most effective, and concludes with demonstrated techniques for teaching effective learning strategies.

How Students Tend to Approach Learning

A pervasive theme in the literatures of both educational psychology and information literacy instruction is that students benefit from being explicitly taught how to learn. Teachers and librarians tend to assume that students learned how to learn before entering college. But in fact, few incoming college students have received adequate instruction in and practice with effective learning techniques. Consequently many students approach learning tasks in ineffective ways. Head (2013) found that inadequate preparation in high school and deeply ingrained habits of using Google have left the majority of college students ill prepared to conduct college–level research. Experienced research and instruction librarians are well aware of the challenges first year students face. For example, Silva (2013) describes students’ need for instruction and practice in formulating keywords, understanding the limitations of databases and search engines, evaluating sources, and following citations.

Even when they are able to find adequate sources, many students employ shortcuts to reduce the time they should devote to appropriately engage with text. This is a problem for writers of research papers because copying is not composing, and “patchwriting” (cobbling together bits and pieces altered just enough to avoid outright plagiarism) indicates lack of engagement and understanding (Pecorari, 2003). Almost 94 percent of students drew from sentences in sources, and 70 percent of those citations were from the first two pages of articles. In their study on the prevalence of patchwriting (aka sentence-mining), Jamieson & Howard (2013) found that rather than synthesizing information, almost 94 percent of students drew from sentences in sources, and 70 percent of those citations were from the first two pages of articles. This sentence-mining approach is not conducive to becoming information literate, learning to synthesize ideas, or developing the ability to base arguments on evidence (Jamieson & Howard, 2013).

Some of the most interesting and relevant scholarship on teaching and learning comes from writing center professionals, several of whom have drawn from research in both educational psychology and information literacy. For example, Nelson (1992) conducted a qualitative study of students’ research habits very similar to the contemporaneous work of Kuhlthau (1991). Nelson (1992) described how students faced with writing a research paper must choose between the easy path of summarizing sources and shoving in a few quotes versus the hard path of extensive research and careful analysis of different points of view. Nelson (1992) concluded that paper assignments should be designed to encourage genuine investment along the hard path, by requiring students to submit drafts and by teachers providing timely formative feedback. Formative assessment is particularly important because it allows students to productively learn from mistakes without suffering a grade penalty.

However, many classroom instructors fail to provide ungraded feedback because formative assessments are time consuming. It can be difficult from the instructor’s point of view to see the value in investing considerable effort into assessments that will not count toward the course grade. Conversely, students may take the perspective that if it doesn’t count toward the grade, it’s not worth bothering to waste effort on a version that will receive only formative, non-graded feedback. Librarians are well positioned to provide formative feedback on at least some aspects of the research process, since students know we will not (usually) be responsible for assigning grades. Absent interim requirements for formative feedback, students are very likely to take the easy path and use sentence-mining to cobble together sources rather than intellectually engage in the research project. In our experience, it is often necessary to communicate to students that course requirements do not have to equate with a grade requirement, and to explain the educational benefits of formative evaluations of their work.

Brent (2013) argues that in order to achieve the goals of a liberal education, instructors need to find “good ways to introduce students to the process of getting in touch with the conversation of scholars and learning gradually to speak their language” (p. 41). To achieve that, students must overcome their propensities to use low-investment strategies like sentence-mining and patchwork. Deeper engagement can be encouraged by assigning reader responses, log entries or other forms of ongoing reporting during the research process. Requiring self-reflective activities requires instructors to invest a substantial amount of time, but the potential increase in meta-cognitive awareness of the learning process pays off in student achievement (Brent, 2013).

The principles in the Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education (American Library Association, 2015) are obviously directly applicable to the problems Brent (2013) described. In more recent work, Brent (2017) investigated the degree to which college seniors recognized scholarship as conversation and identified themselves as having a role in that conversation. The short answer is that few reach that level of engagement, and lack of time is often blamed. Several of the students Brent (2017) interviewed made “clear that intellectual curiosity was a luxury that time pressure could easily make unaffordable” (p. 353). Intellectual curiosity is a luxury that time pressure can make unaffordable.Alexander (2018) distinguishes between students coping with limited time by managing information versus engaging in the more time intensive process of knowledge building.

The expectancy-value theory of motivation incorporates intellectual curiosity into the value component of motivation to learn (Eccles & Wigfield, 2002). The four elements of the value component of being motivated to engage in an academic task are: 1) Do I see value in the task in that it will help me attain something I desire (attainment value), 2) Do I see value in the task in that it will be of use to me (utility value), 3) Do I have an intrinsic interest in the task (intrinsic value), and 4) What do I have to give up in order to complete the task (cost). If the learning activity impedes engaging in other desirable activities, the learning task is likely to be perceived as a luxury. The opportunity cost of the learning task may simply be too high relative to the student’s desire to spend time on other assignments, socializing with friends, playing sports, sleeping, and so on. One way to nudge students toward fuller engagement despite the cost of doing so is to share one’s own professional experiences. Brent (2017) found that students rarely properly understood the role of research in their teachers’ professional lives, and he suggested that it can be powerfully enlightening and motivating to discuss with students one’s current research projects, including the costs and benefits of devoting considerable time to those projects.

Rabinowitz (2000) pointed out the striking similarities between research findings on student behaviors conducted by librarians, composition experts, and faculty within various disciplines, and urged librarians to redouble our efforts to collaborate with writing centers and English faculty. A noteworthy example of drawing from the knowledge of composition experts is Fister’s (1993) description of how and why to teach the rhetorical dimensions of research. By that she means librarians should instruct students to read to detect the implied audience, the author’s argument, and the evidence used to support the argument (Fister, 1993). Chapter 12 includes a more in-depth treatment of the benefits of collaborations.

How Students Should Approach Learning

The majority of empirical research on students’ learning strategies measures how well individuals perform on tests or their ability to recall information. For example, there happen to be many studies of students’ abilities to describe how the circulatory system works and of abilities to memorize word pairs. A very large body of research on memory and cognition has investigated effective techniques for improving short-term and working memory (e.g. Turkington, 2003). Our interest here is in techniques that promote long-term learning rather than techniques to improve one’s ability to regurgitate information. Of particular relevance is Dunlosky and colleagues’ meta-analysis of effective study strategies, which was designed to identify “robust, durable results . . . relevant in many situations” (Dunlosky, Rawson, Marsh, Nathan, & Willingham, 2013, p. 48). Table 1 summarizes years of research findings on effective strategies for long-term learning (Dunlosky, 2013), and is reproduced with the publisher’s permission.

Table 1: Effectiveness of Learning Strategies

| Technique | Extent and Conditions of Effectiveness |

| Practice testing | Very effective under a wide array of situations |

| Distributed practice | Very effective under a wide array of situations |

| Interleaved practice | Promising for math and concept learning, but needs more research |

| Elaborative interrogation | Promising, but needs more research |

| Self-explanation | Promising, but needs more research |

| Rereading | Distributed rereading can be helpful, but time could be better spent using another strategy |

| Highlighting and underlining | Not particularly helpful, but can be used as a first step toward further study |

| Summarization | Helpful only with training how to summarize |

| Keyword mnemonic | Somewhat helpful for learning languages, but benefits are short-lived |

| Imagery for text | Benefits limited to imagery-friendly text, and needs more research |

Cramming can work for immediate recall, but what really matters is genuine learning that sticks over time. The short answer for what works over time is strategies that cause students to actively process content and connect it with their prior knowledge (Dunlosky, 2013). Educational psychologists acknowledge that cramming can work to achieve certain tasks, but the evidence is strong that little if any long-term benefits are gained from cramming. Unfortunately there have been few studies on long-term educational benefits of specific learning strategies, because it is very difficult to isolate the impact of a particular strategy among the many variables that influence learning. Long term transfer of learning has been described as the “holy grail in educational research” (Rawson, Dunlosky, & Sciartelli, 2013, p. 543). Long term transfer of learning has been described as the “holy grail in educational research.” In order to accurately determine the long term effects of a learning strategy, researchers need to perform longitudinal research with students to measure what they remember about specific information over time and control for extraneous variables. Such a longitudinal study would need to compare test results for students who crammed against students who used more of the effective strategies listed in Table 1. Given the complexity of real students’ educational experiences, it will always be difficult if not impossible to determine for sure that specific long term outcomes were due to a particular activity.

Despite the difficulties in accurately assessing the impact of a particular strategy on long term retention of learning, the evidence is strong for the positive effects of successive relearning. Successive relearning is defined as multiple successful retrievals of information across days or weeks (Rawson et al., 2013). To effectively apply successive relearning, students have to identify the information to be learned, retrieve the information at some point after it is first learned, accurately judge whether the information was retrieved correctly, and manage the time spent on information retrieval (Rawson et al., 2013). The corollary for writing a research paper is to revisit sources and rethink how they fit into the paper over successive sessions, versus cramming the information into one frenzy of writing. Research supports the common sense notion that spacing research and writing over time is educationally more effective than procrastinating and doing it all the night before.

Educational psychologists’ findings regarding effective study strategies may not all be directly applicable to students’ research processes, but we believe it is useful to summarize the main findings here. Librarians may not often be directly involved in helping students study for tests, but knowing which strategies do and do not work could come in handy, and the general principles are broadly applicable to college students’ overall academic behaviors.

The first thing we should get out of the way is learning styles theory, which is one of the most commonly known theories about learning strategies. Despite its pervasiveness among teachers and parents, the idea that students have preferences for how to receive information and that they will have better learning outcomes if instruction matches those preferences has been debunked (Willingham, Hughes, & Dobolyi, 2015). There are variations to learning styles theory, but the theory generally states that individuals have preferences for visual, auditory, and kinesthetic means of processing information, and that they will learn better if material is presented to them in their preferred format. While it is impossible to prove that something does not exist, “there is no viable evidence to support the theory” (Willingham et al., 2015, p. 267). Learning styles theory has been debunked. Whether material is presented in visual versus auditory versus kinesthetic modes has been found to make no significant difference in learning outcomes, although instructors should still recognize and adapt instruction to individual differences in ability, interest, prior knowledge, and to accommodate disabilities (Riener & Willingham, 2010). Learning styles theory has been criticized for distracting teacher’s attention away from the more important goal of presenting material in multiple ways to promote diverse students’ interest and engagement (Toppo, 2019). It is very important to note the difference between learning preferences that students have towards how they learn something verses proven strategies that effectively help students to learn. Learning styles theory is distinct from differentiated instruction and Universal Design for Learning, which are described in Chapter 6. Styles have not been shown to produce superior learning outcomes, but strategies that promote engagement have been shown to make real differences in academic achievement.

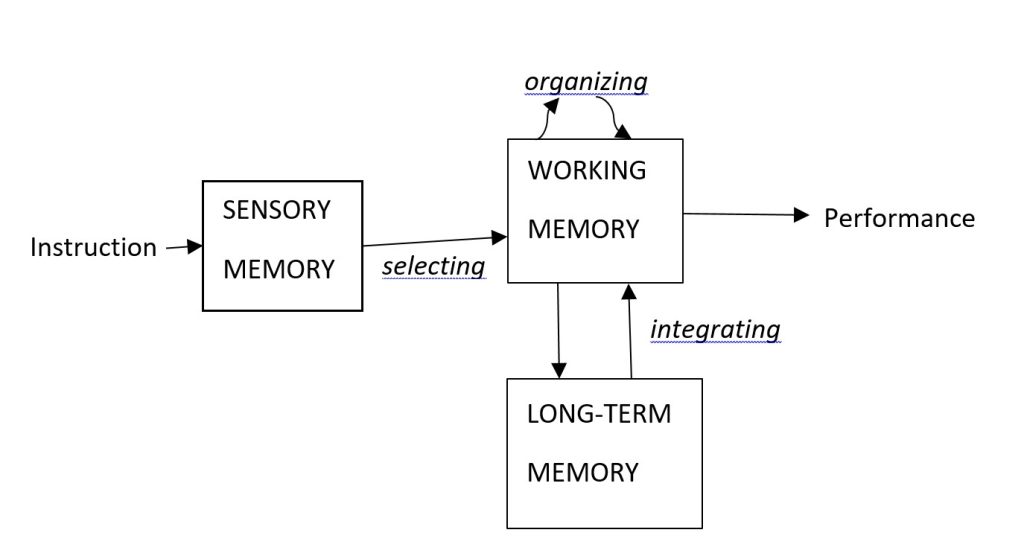

Fiorella & Mayer (2015) asserted that genuine engagement requires individuals to select, organize, and integrate information, a process they call generative learning. The idea of generative learning has deep roots in cognitivism, which was in part a reaction to the idea that learning occurs through operant conditioning. According to the cognitivists, learning is not simply inputs and outputs, but rather is based on the premise that “people tend to generate perceptions and meanings that are consistent with their prior learning” (Wittrock, 2010, p. 41). People generate and transfer meaning of stimuli and events from their individual backgrounds, attitudes, abilities and experiences (Wittrock, 2010).

Put another way, students generate learning by attending to relevant material, organizing material into coherent cognitive structures, and connecting new information with knowledge stored in long-term memory. The Selecting-Organizing-Integrating model of generative learning Fiorella & Mayer (2015) is depicted in Figure 1 and is reproduced with permission of the publisher.

Figure 1: The Selecting—Organizing—Integrating Model of Generative Learning

Fiorella & Mayer (2015) describe eight learning strategies that support generative learning:

- summarizing

- mapping

- drawing

- imagining

- self-testing

- self-explaining

- teaching

- enacting

The authors’ meta-analyses of published research on the effectiveness of these strategies showed median effect sizes of no less than .43 and as much as 1.07 (Fiorella & Mayer, 2015). That is, students who used these learning strategies performed from .43 to 1.07 standard deviations better than students who did not use the strategies. (For a full explanation of how effect sizes are calculated and interpreted in educational research see Hattie (2009)).

Teaching Students Effective Learning Strategies

Research on learning strategies has produced a fairly stable list of strategies and well-founded evidence for what works. The next step for educational psychologist and teachers is to experiment with methods for teaching effective learning strategies. The desirability of explicit instruction in learning strategies has been recognized for decades within both K-12 (Weinstein & Mayer, 1986) and higher education (McKeachie, Pintrich, & Lin, 1985). A consistent theme in the literature on successful study skills programs is an emphasis on metacognition and self-awareness. Burchard & Swerdzewski (2009) found that instruction in learning strategies led to significant improvements in self-awareness and self-regulation. Tuckman & Kennedy (2011) created and administered a course to help students overcome procrastination, build self-confidence, take responsibility, remember material presented in lecture and text, study for exams, write papers, and generally manage their time. Instruction in specific learning strategies led to students having significantly better grades and graduation rates than comparable students who did not take the course (Tuckman & Kennedy, 2011). Learning effective strategies thus not only improves metacognition but can also result in higher academic achievement. Instruction in learning strategies can improve self-awareness and self-regulation.

The instructive article “Optimizing Learning in College” (Putnam, Sungkhasettee, & Roediger, 2016) is written specifically for college students and suggests concrete actions they can use to apply the proven learning strategies. Suggestions include visualizing the chronological landscape of the semester, self-generating questions about readings and lectures, self-quizzing, and spacing out studying (Putnam et al., 2016). Although spacing can be difficult to implement, students who are re-exposed to information are more likely to retain it over the long term (Carpenter, Cepeda, Rohrer, Kang, & Pashler, 2012).

A strategy that is directly applicable to resource-based projects is self-explanation. Teaching students to generate their own explanations of what something means helps them construct meaning, integrate new information with prior knowledge, and provide opportunity to detect and correct misunderstandings (Chi, de Leeuw, Chiu, & LaVancher, 1994). The authors of a recent meta-analysis explained that “Self-explanation is directed toward one’s self for the purpose of making new information personally meaningful. Because it is self-focused, the self-explanation process may be entirely covert or, if a self-explanation is expressed overtly, it may be intelligible only to the learner” (Bisra, Liu, Nesbit, Salimi, & Winne, 2018, p. 704). Prompting students to come up with their own explanations can be more effective than having the instructor provide explanations, although self-explanation can take more time (Bisra et al., 2018). The self-explanation strategy does have limits. It has been found to be less effective than teachers’ explanations if the material being learned is an exception to known rules or if students are prone to confuse similar but distinct ideas (Rittle-Johnson & Loehr, 2017). Despite those limitations, reference and instruction librarians should take advantage of opportunities to prompt students to explain what new information means to them.

Desirable Difficulties

All these effective learning strategies require effort on the part of students. The point for instructors is not to make things easy, but rather to find optimal levels of challenge. Bjork, Dunlosky, & Kornell (2013) used the term “desirable difficulties” to describe appropriate challenges and responses that lead to long-term retention of and ability to transfer information. The short-term cost of studying in more difficult ways pays off with improved long-term learning. It takes time and effort to interleave practice sessions, pose questions about material and self-generate answers, quiz oneself, and vary the conditions of learning (i.e. applying new knowledge in multiple contexts), but that effort pays off in the long term (Bjork et al., 2013). The essential point about desirable difficulties is that if it seems easy, probably little is being learned. Detecting and correcting errors and mistakes is fundamental to effective learning.

In their review of the potential benefits of allowing (or even inducing) students to commit errors, Wong & Lim (2019) stated “although errors can be costly, perhaps the costs to be borne are even greater when learners do not maximize their gains from adopting more active learning strategies that effectively manage errors, which invariably arise during the naturalistic acquisition of knowledge” (p. 4). Errors students may make during library research can actually benefit their long-term learning. Librarians cannot prevent students from making mistakes like choosing an inappropriate database or selecting imprecise search terms. But we can help students a great deal by providing specific feedback about how to adjust their search strategies after they have made errors.

Garner (1990) described five reasons why learners may avoid taking the time to apply effective learning strategies: illusion of comprehension, ingrained (but ineffective) study habits, lack of foundational knowledge, ability attributions, and unawareness that a learned technique is applicable in a novel situation. Illusion of comprehension means being unaware of what one does not know and of the gaps between one’s knowledge or skills and the expectations of the instructor. Habits like highlighting, re-reading, or copying can die hard, even if these activities are ineffective. Students’ overreliance on Google reported by Head (2013) is an example of ingrained but ineffective habits. Lack of prior knowledge inhibits the ability to make analogies and connections. Ability attributions such as telling oneself “I’m just no good at this” impede effort to learn. Finally, absent direct prompts, students may fail to recognize that a learning strategy like how to use a particular database can be applicable to a new assignment (Garner, 1990). Learners miss effective learning strategies due to illusion of comprehension, ingrained study habits, lack of knowledge, ability attributions, and unawareness that a technique is applicable.

This point that students need to apply themselves, be engaged, and work through desirable difficulties is hardly news to reference and instruction librarians. The Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education (American Library Association, 2000) and the newer Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education (American Library Association, 2015) are firmly rooted in the conviction that students must genuinely engage with sources, apply critical thinking, and develop metacognitive strategies to self-monitor their research processes. Catalano (2017) developed a Metacognitive Strategies for Library Research Skills Scale to assess the degree to which students are aware of expectations, can self-check for effective strategies, are able to plan, and can evaluate sources. Whether an instructor uses such an instrument or not, it is important to convey to students the utility of intentionally tracking one’s thoughts and activities during a research project.

A venerable method for prompting metacognition is to require students to keep a research log. “Research log/research journal assignments ask students to keep track of their research processes and produce an artifact—a log, a journal, a story—describing and reflecting on that process” (Fluk, 2015, p. 488). Fluk (2015) explains that despite strong theoretical backing and many practical uses, the time and effort required to complete research logs has hindered their application. Apparently the difficulty overwhelms the desirability. Research logs are another example of expectancy-value theory of motivation, in that the expected cost may be perceived to be greater than the value of the exercise. If the students in a class widely perceive the cost to outweigh the benefits, one approach is to make the research log a required, grade-bearing part of a research assignment. Alternatively, one may explain that the assignment is a requirement of the course, even if it is not grade-bearing. As mentioned above, the task can be described as valuable formative monitoring and assessing of one’s academic work. Due to the time involved by both students and instructors to keep and give feedback on research logs, it’s important that the logs clearly match stated learning course objectives.

The process of learning to use library resources to create an original piece of research is surely a desirable difficulty. Many of the effective learning strategies presented here are applicable to library research, including distributing work over time, revisiting work over multiple sessions, and interleaving work on a project with other activities. All require time and effort. As librarians we can help students apply their time and effort more efficiently, and provide assurance that the long-term value of doing research and building information literacy is indeed worth the cost.

Takeaways for Librarians

- Do not assume that college students have been taught effective learning strategies.

- If asked, counsel the instructors who create research assignments to emphasize quality of intellectual engagement over quantity of sources, to help dissuade students from merely sentence-mining to cobble together sources.

- Talk with students about your own research processes to help them grasp the concept of scholarship as conversation.

- Continue and expand collaborations with writing centers and English faculty.

- Learning styles theory has been debunked, despite its continued widespread acceptance among teachers, students, and parents. Whether material is presented in visual versus auditory versus kinesthetic modes has been found to make no significant difference in learning outcomes.

- Avoiding procrastination and spacing out the research process have been confirmed by multiple studies to be just as important as we’ve always known good time management to be for academic success.

- Tell students that generating their own questions about what they are reading and formulating their own explanations are effective learning strategies.

- Acknowledge to students that you know the research process is not easy, and explain the struggles they will encounter are desirable difficulties that will lead to robust learning.

- Describe to students the benefits of intentionally tracking one’s thoughts and activities during a research project.

Recommended Reading

Bisra, K., Liu, Q., Nesbit, J. C., Salimi, F., & Winne, P. H. (2018). Inducing Self-Explanation: a Meta-Analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 30(3), 703–725. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-018-9434-x

Students self-explain to make new information personally meaningful. Teachers can prompt students to create explanations of causal relationships, make connections among concepts, or supply evidence to support a claim. The authors’ meta-analysis of 64 studies indicates that self-explanation is an effective learning strategy, and they conclude it is worth the time it takes away from presenting more content. The most effective technique is to have students make an initial self-explanation, then revise it after being presented with new information. This allows students to identify and repair gaps in understanding.

Bjork, R. A., Dunlosky, J., & Kornell, N. (2013). Self-regulated learning: Beliefs, techniques, and illusions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 417–444. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143823

Three distinguished psychologists of learning and memory summarize the benefits and potential shortcomings of knowing how to manage one’s own learning. Truly effective learners understand how humans remember, know effective activities and techniques, can self-monitor, and be aware of their biases. Unfortunately students can misinterpret the value of common study techniques and take easier paths than are optimal for long-term learning. The authors describe four desirable difficulties: spacing or interleaving practice, taking time to generate answers of one’s own (even if they turn out to be in error), testing oneself, and varying the conditions of learning.

Dunlosky, J. (2013). Strengthening the student toolbox: Study strategies to boost learning. American Educator, 37(3), 12–21.

Psychologist John Dunlosky has published extensively on the effectiveness of various study strategies. This article summarizes main findings with a nice balance of readability and detail. Dunlosky’s emphasis is on true understanding and long-term memory versus strategies that may only help students regurgitate information they then forget. The most effective strategies are practice testing and distributing practice sessions over time. Other useful strategies are interleaved practice, elaborative interrogation and self-explanation. Strategies that students often use but that have been shown to be ineffective are rereading and highlighting, summarization, mnemonics and imagery. The article concludes with a list of tips for using effective strategies.

Fiorella, L., & Mayer, R. E. (2015). Learning as a generative activity: eight learning strategies that promote understanding. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Distinguished psychology professor Richard E. Meyers and doctoral candidate Logan Fiorella describe how to promote generative learning, meaning that students actively try to make sense of what is being taught. Generative learning is a three part process of selecting what to pay attention to, organizing it into a coherent cognitive structure, and integrating it with prior knowledge to form long-term memories. The eight strategies are summarizing, mapping, drawing, imagining, self-testing, self-explaining, teaching, and enacting. The authors describe how to teach these strategies and present the research evidence for their effectiveness.

Garner, R. (1990). When children and adults do not use learning strategies: Toward a theory of settings. Review of Educational Research, 60(4), 517–529. https://doi.org/10.2307/1170504

Ruth Garner explains that ideally students know when and how to apply effective strategies, yet may fail to do so for five reasons. The first is illusion of comprehension, being unaware of what they do not know. The second is attachment to ineffective strategies like rote copying. Third is lack of foundational knowledge required to put information into context. Fourth is a “why bother” attitude based on belief in fixed ability (versus having a growth mindset). Fifth is a failure to recognize how prior learning can transfer to a new domain.

Nelson, J. (1992). Constructing a research paper: A study of students’ goals and approaches. Technical Report No. 59. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED342019

This is one of a series of naturalistic studies Jennie Nelson conducted on undergraduates’ research processes. She describes two paths to writing a paper: the easy path of assembling quotes and paraphrases with some analysis tacked on, and the harder path of doing genuine analysis of varying points of view. How an assignment is constructed directly influences which path students will take. Instructors should require students to submit early drafts and emphasize the importance of taking ownership of the investigative process. Nelson’s work very nicely complements (and parallels) librarian Carol Kuhlthau’s investigations into the undergraduate research process.

Putnam, A. L., Sungkhasettee, V. W., & Roediger, H. L. I. (2016). Optimizing learning in college: Tips from cognitive psychology. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11(5), 652–660. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616645770

This concise summary of research findings on effective learning strategies is written for college students and those who advise them. The references comprise a useful bibliography of the relevant research. The strategies are summarized in five categories: space out your learning, learn more by testing yourself, get the most out of class sessions, be an active reader, and manage your time. While this is a useful overview of applicable research, the authors unfortunately focus on succeeding on tests and do not specifically address the research process.

Silva, M. L. (2013). Can I Google that? Research strategies of undergraduate students. In R. McClure & J. P. Purdy, The New Digital Scholar (pp. 161–187). Medford, NJ, USA: Information Today.

Mary Lourdes Silva is a professor of language, literacy, and composition with research interests that draw heavily on educational psychology. In this chapter of a book focused on teaching NexGen students to be information literate, Silva describes her study of students’ online navigation behaviors. Her findings confirm what instruction librarians know about students’ struggles with finding appropriate keywords, understanding the limitations of databases, and navigating citation trails. The chapter includes two appendices of guidelines for teaching students effective navigational strategies and developing a self-regulated approach to research.

Tuckman, B. W., & Kennedy, G. J. (2011). Teaching learning strategies to increase success of first-term college students. Journal of Experimental Education, 79(4), 478–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2010.512318

Bruce Tuckman and Gary Kennedy describe a course on strategies for academic achievement taught at Ohio State University. The course is based on setting bite-sized goals, taking responsibility, searching the environment for information, and using feedback. Students enrolled in a course to learn these strategies had higher grades and were more likely to graduate. The authors assert that setting clear expectations and a firm timetable are key to a successful learning strategies course.

Willingham, D. T., Hughes, E. M., & Dobolyi, D. G. (2015). The scientific status of learning styles theories. Teaching of Psychology, 42(3), 266–271. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628315589505

The idea that students learn best if the method of instruction matches individual preferences for auditory, visual, or kinesthetic inputs is widely accepted but unsupported by the evidence. The authors explain that while individual students may have preferences for how information is received, these preferences do not result in measurable differences in learning outcomes. They make the point that in practical terms teachers are better off focusing on methods that work for all students.

Works Cited

Alexander, P. A. (2018). Information management versus knowledge building: Implications for learning and assessment in higher education. In O. Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, M. Toepper, H. A. Pant, C. Lautenbach, & C. Kuhn (Eds.), Assessment of learning outcomes in higher education: Cross-national comparisons and perspectives (pp. 43–56). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-74338-7_3

American Library Association. (2000). Information literacy competency standards for higher education. Retrieved from https://alair.ala.org/handle/11213/7668

American Library Association. (2015). Framework for information literacy for higher education. Retrieved March 14, 2018, from Association of College & Research Libraries (ACRL) website: http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework

Bisra, K., Liu, Q., Nesbit, J. C., Salimi, F., & Winne, P. H. (2018). Inducing self-explanation: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 30(3), 703–725. doi:10.1007/s10648-018-9434-x

Bjork, R. A., Dunlosky, J., & Kornell, N. (2013). Self-regulated learning: Beliefs, techniques, and illusions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 417–444. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143823

Brent, D. (2017). Senior students’ perceptions of entering a research community. Written Communication, 34(3), 333–355. doi:10.1177/0741088317710925

Brent, D. (2013). The research paper and why we should still care. Writing Program Administration, 37(1), 21.

Burchard, M. S., & Swerdzewski, P. (2009). Learning effectiveness of a strategic learning course. Journal of College Reading and Learning, 40(1), 14–34. doi:10.1080/10790195.2009.10850322

Carpenter, S. K., Cepeda, N. J., Rohrer, D., Kang, S. H. K., & Pashler, H. (2012). Using spacing to enhance diverse forms of learning: Review of recent research and implications for instruction. Educational Psychology Review, 24(3), 369–378. doi:10.1007/s10648-012-9205-z

Catalano, A. (2017). Development and validation of the Metacognitive Strategies for Library Research Skills Scale (MS-LRSS). Journal of Academic Librarianship, 43(3), 178–183. doi:10.1016/j.acalib.2017.02.017

Chi, M. T. H., de Leeuw, N., Chiu, M.-H., & LaVancher, C. (1994). Eliciting self-explanations improves understanding. Cognitive Science, 18(3), 439–477. doi:10.1207/s15516709cog1803_3

Dunlosky, J. (2013). Strengthening the student toolbox: Study strategies to boost learning. American Educator, 37(3), 12–21.

Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K. A., Marsh, E. J., Nathan, M. J., & Willingham, D. T. (2013). What works, what doesn’t. Scientific American Mind, 24(4), 46–53. doi:10.1038/scientificamericanmind0913-46

Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2002). Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(1), 109–132. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135153

Fiorella, L., & Mayer, R. E. (2015). Learning as a generative activity: Eight learning strategies that promote understanding. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Fister, B. (1993). Teaching the rhetorical dimensions of research. Research Strategies, 11(4), 211–219.

Fluk, L. R. (2015). Foregrounding the research log in information literacy instruction. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 41(4), 488–498. doi:10.1016/j.acalib.2015.06.010

Garner, R. (1990). When children and adults do not use learning strategies: Toward a theory of settings. Review of Educational Research, 60(4), 517–529. doi:10.2307/1170504

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: a synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. New York, NY, US: Routledge.

Head, A. J. (2013). Learning the ropes: How freshmen conduct course research once they enter college. SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2364080

Jamieson, S., & Howard, R. M. (2013). Sentence-mining: Uncovering the amount of reading and reading comprehension in college writers’ researched writing. In R. McClure & J. P. Purdy (Eds.), The new digital scholar: Exploring and enriching the research and writing practices of nextgen students (pp. 109–131). Medford, NJ, USA: Information Today.

Kuhlthau, C. C. (1991). Inside the search process: Information seeking from the user’s perspective. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 42(5), 361–371. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4571(199106)42:5%3C361::AID-ASI6%3E3.0.CO;2-%23

McKeachie, W. J., Pintrich, P. R., & Lin, Y. (1985). Teaching learning strategies. Educational Psychologist, 20(3), 153–160. doi:10.1207/s15326985ep2003_5

Nelson, J. (1992). Constructing a research paper: A study of students’ goals and approaches. Technical Report No. 59. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED342019

Pecorari, D. (2003). Good and original: Plagiarism and patchwriting in academic second-language writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 12(4), 317–345. doi:10.1016/j.jslw.2003.08.004

Putnam, A. L., Sungkhasettee, V. W., & Roediger, H. L. I. (2016). Optimizing learning in college: Tips from cognitive psychology. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11(5), 652–660. doi:10.1177/1745691616645770

Rabinowitz, C. (2000). Working in a vacuum: A study of the literature of student research and writing. Research Strategies, 17(4), 337–346. doi:10.1016/S0734-3310(01)00052-0

Rawson, K. A., Dunlosky, J., & Sciartelli, S. M. (2013). The power of successive relearning: Improving performance on course exams and long-term retention. Educational Psychology Review, 25(4), 523–548. doi:10.1007/s10648-013-9240-4

Riener, C., & Willingham, D. T. (2010). The Myth of Learning Styles. Change, 42(5), 32–35.

Rittle-Johnson, B., & Loehr, A. M. (2017). Eliciting explanations: Constraints on when self-explanation aids learning. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 24(5), 1501–1510. doi:10.3758/s13423-016-1079-5

Silva, M. L. (2013). Can I Google that? Research strategies of undergraduate students. In R. McClure & J. P. Purdy, The New Digital Scholar (pp. 161–187). Medford, NJ, USA: Information Today.

Toppo, G. (2019, January 9). In learning styles debate, it’s instructors vs. psychologists. Retrieved from: https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2019/01/09/learning-styles-debate-its-instructors-vs-psychologists

Tuckman, B. W., & Kennedy, G. J. (2011). Teaching learning strategies to increase success of first-term college students. Journal of Experimental Education, 79(4), 478–504. doi:10.1080/00220973.2010.512318

Turkington, C. (2003). Memory: A self-teaching guide. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Weinstein, C. F., & Mayer, R. E. (1986). The teaching of learning strategies. In M. C. Wittrock (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching (Vols. 1–Book, Section, pp. 315–372).

Willingham, D. T., Hughes, E. M., & Dobolyi, D. G. (2015). The scientific status of learning styles theories. Teaching of Psychology, 42(3), 266–271. doi:10.1177/0098628315589505

Wittrock, M. C. (2010). Learning as a generative process. Educational Psychologist, 45(1), 40–45. doi:10.1080/00461520903433554

Wong, S. S. H., & Lim, S. W. H. (2019). Prevention–permission–promotion: A review of approaches to errors in learning. Educational Psychologist, 54(1), 1–19. doi:10.1080/00461520.2018.1501693