Steve Black; James D. Allen; and Debbie Krahmer

This chapter was originally published as Black, S., Krahmer, D., & Allen, J. D. (2018). Insights from educational psychology part 6: Diversity and inclusion. The Reference Librarian, 59(2), 92–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763877.2018.1451425. Debbie Krahmer, Accessible Technology & Government Documents Librarian at Colgate University, contributed to this chapter.

Chapter 5 on learning as a social act summarized the powerful evidence that exposure to diverse perspectives improves learning. Students who engage with different points of view learn more broadly and deeply. In this column we describe more thoroughly why this is so, and provide guidance on how librarians might incorporate diversity into reference and instruction.

Diversity and Cognitive Development

Psychologist Erik Erikson asserted that late adolescence and early adulthood are critical stages in individuals’ formation of personal and social identity (Erikson, 1980). In order to develop a robust identity, college students need to confront diverse perspectives and become aware of discontinuities from prior notions. Disequilibrium between preconceptions and new perspectives causes students to struggle with new ideas and self-reflect on the meaning of different viewpoints for themselves and their social group. Effective learning includes grappling with cognitive conflicts that cause uncertainty, doubt, and perhaps anxiety (Gurin, Dey, Hurtado, & Gurin, 2002). Engaging with this disequilibrium may be uncomfortable, but it is an essential part of a meaningful college education. Those necessary states of growth are less likely to occur absent interaction with diverse peers. It is important for college students to interact with diverse peers and engage in civil discussions of discordant points of view, not only for themselves but also for the good of society. Society needs citizens capable of taking perspective, accepting conflict as a normal part of life, and accurately perceiving differences and commonalities among people (Gurin et al., 2002).

Empirical support for the notion that diversity supports educational outcomes is compelling. A prominent longitudinal study concluded that “the actual experiences students have with diversity consistently and meaningfully affect important learning and democracy outcomes of a college education” (Gurin et al., 2002, p.358). Bowman’s (2010) meta-analysis of the effects of college diversity experiences on cognitive development concluded that there is strong evidence that interpersonal interactions with racial and nonracial diversity, diversity coursework, and diversity workshops are positively related to cognitive development. Exposure to racial and cultural diversity promotes problem solving, critical thinking, cognitive development, and complexity of thinking. Interpersonal interactions with diverse perspectives are likely to trigger disequilibrium and effortful thinking, which contributes to cognitive development and sophisticated critical thinking (Bowman, 2010). Studies have linked exposure to racial and cultural diversity to growth in problem solving, critical thinking, cognitive development, and complexity of thinking (Pascarella et al., 2014).

One of us (James Allen) team-taught undergraduate courses that integrated specific learning activities and assignments designed to improve intercultural understanding. Three strategies were employed: a personal diversity experience, cultural conflict vignettes, and a cultural diversity interview. Requiring preservice teachers to engage with diversity in these ways created cognitive disequilibrium and effectively spurred the students to reflect on their preconceptions (Allen, Bower, & Miller, 2004).

One way to view the impact of diversity on identity development is through the lens of self-authorship. Normal growth into adulthood includes a process of moving from being externally defined by parents and others to creating an internal self-definition rooted in social relationships (Kegan, 1994). Finding the fit between personal beliefs and social environment is key to healthy adult development. The process of self-authorship should include development of intercultural maturity. The process of developing intercultural maturity starts with following external formulas, such as what one has learned from parents and teachers in school. Assuming one is exposed to diverse points of view, the typical next phase of self-authorship is to experience crossroads when those learned perspectives are challenged. Engagement and self-reflection underpins the ability to follow internal voices to resolve challenges to learned perspectives (Perez, Shim, King, & Baxter Magolda, 2015). Exposure and openness to diversity is essential for this growth to occur. “When we assume that our constructions are ‘the way the world is’ rather than the way we have constructed it, we assume constructions unlike ours are not legitimate” (Perez et al., 2015, p.760). Intercultural expertise requires understanding cultural differences, developing the ability to not feel threatened by cultural differences, and learning to interact respectfully with diverse others (Perez et al., 2015). All of that requires engagement with people different from oneself. Learning about diverse groups can be enlightening, but intergroup contact is also needed to fully develop intercultural maturity (Bowman, 2010).

The Intergroup Dialogue (IGD) program (Zúñiga, Lopez, & Ford, 2014) provides a model for how intercultural maturity may be accomplished. Intergroup dialogue (or intergroup relations) is a pedagogical tool for meaningful engagement among people from diverse backgrounds, especially in areas of conflict. IGD’s pedagogical goal is to facilitate dialogue that leads people to challenge points of view, self-reflect, and engage with individuals different from themselves. Intergroup dialogue (or intergroup relations) is a pedagogical tool for meaningful engagement among people from diverse backgrounds, especially in areas of conflict. Intergroup dialogue is a tool for meaningful engagement among people from diverse backgrounds. Influenced by democratic and popular education theorists such as John Dewey and Paulo Freire, intergroup dialogue involves facilitated small group experiences designed to promote active, engaged, and emotionally-challenging learning about differences and social justice from perspectives of psychology and sociology, interaction with diverse peers, and critical self-reflection (Gurin, Nagda, & Zúñiga, 2013). The goal is to create a brave, co-learning environment where people of diverse backgrounds can not only gain understanding and empathy about the perspectives of others, but also increase personal awareness of the complex roles race, prejudice and culture play in the processes of self-authorship. It is about bravery, not safety. The final stage of IGD focuses on building alliances and taking action based on the learning experience, so that the dialogue participants are always moving forward and growing. Intergroup dialogue helps people break the silence surrounding conflict within racial and other forms diversity and learn to find their voice. “At its heart, intergroup dialogue is a sustained, intentional effort to bring diverse people together to collectively build something greater than any of us as individuals may accomplish. It requires respect for divergent voices, value for the unique and shared responsibilities individuals bring to the collective good, and a concerted effort to listen and understand multiple experiences and perspectives that derive from people’s different connections to power and privilege” (Gurin et al., 2013, p. xiii).

Sense of Belonging

Chapter 5 on learning as a social act included a description of the reciprocal interactions of environment, personal characteristics, and behaviors in educational settings (Bandura, 1989). Environment influences behaviors which influence personal characteristics. Personal characteristics and behaviors in turn influence the learning environment. An important aspect of this reciprocal triad for college students is the degree to which the environment allows one to feel at home and experience a sense of belonging. “When students experience [a] strong connection between their selves and what it means to attend and perform well in college, they will gain a sense that they fit in the academic environment and will be empowered to do what it takes to succeed there” (Stephens, Brannon, Markus, & Nelson, 2015, p. 1). To succeed in college, a student’s process of self-authorship needs to include a sense that school is part of who they are and school is needed to achieve personal goals. Identification of school with self includes feeling that one fits in and deserves to be there. A student who experiences a supportive college environment that helps them develop a school-relevant self is more likely to be engaged, motivated, and academically successful (Stephens et al., 2015). Building relationships with peers, instructors, librarians, and administrators is a necessary part of developing a sense of belonging in college.

The process of forming a self-concept that includes a sense of belonging in college may be more difficult for individuals who experience stigma due to their race, culture, or disability status. “In academic and professional settings, members of socially stigmatized groups are more uncertain of the quality of their social bonds and thus more sensitive to issues of social belonging” (Walton & Cohen, 2007, p. 82). A consequence of feeling uncertain that one belongs is that uncomfortable interactions, such as microaggressions, may create exaggerated magnified negative effects for individuals who already feel stigmatized in a particular environment. Some actions, such as normalizing doubts about social belonging, can help students feel they belong and can effectively reduce the risk of feeling stigmatized. Actions to help students feel they belong can effectively reduce the risk of feeling stigmatized. Walton and Cohen (2007) found that helping Black first-year students realize that all first-year students experience feelings of hardship and doubt helped boost sense of belonging. Simply becoming aware that uncertainty regarding whether one belongs is not unique helped boost sense of belonging among minority first-year students. Sense of belonging is important to all students, but it is especially salient to members of stigmatized groups.

Librarians, professors, staff and administrators play important roles in the creation of learning environments that invite students to feel they belong. In a study of colleges that are particularly inviting to ethnic minority students, Museus (2011) described four themes consistent among inviting campus cultures: strong family-like network, commitment to targeted support, belief in humanizing the educational experience, and an ethos of institutional responsibility for being responsible and reaching out proactively to make ethnic minority students feel at home. Inviting campus cultures have a family-like network, target support, humanize education, and proactively make ethnic minority students feel at home. One aspect of this is for librarians and everyone else on a campus to be culturally competent. Sharing ethnic background with an instructor can be a factor in student-teacher interactions, but a student believing a teacher or librarian is culturally aware and non-biased is also important (Brown & Dobbins, 2004). The implication for librarians is that we all need to develop intercultural expertise. That means understanding cultural differences, developing the ability to not feel threatened by cultural differences, and learning to interact respectfully with diverse others (Perez et al., 2015).

The need for intercultural expertise applies as well to college students with disabilities. Research on students with disabilities’ sense of belonging and satisfaction parallel research focused on students from ethnic minorities, except research on students with disabilities tends to place greater emphasis on self-advocacy. There are reciprocal interactions among sense of belonging, campus climate, ability to self-advocate and satisfaction with the college experience. An increased sense of belonging helps students with disabilities self-advocate with professors and pursue social relationships with peers (Fleming, Oertle, Plotner, & Hakun, 2017). Training students how to self-advocate can improve sense of belonging by signaling to students with disabilities they are in an environment that fully supports their needs. A small group workshop on how to advocate for accommodations was found to significantly improve student’s ability to request fulfillment of their needs (Palmer & Roessler, 2000). The workshop consists of modeling and then practicing how to introduce oneself, propose a solution, identify resources, agree on a plan of action, and close with verification of what is agreed upon and a positive statement of appreciation. The workshop is reminiscent of the elements of a successful reference interview, as it emphasizes the need to articulate the need, identify resources, and clarify who is responsible for performing which parts of the research process. Similar workshops as well as other support mechanisms demonstrate an ethos of institutional responsibility for welcoming students with disabilities.

A key then to creating and maintaining an inviting climate is to increase cultural competence throughout the organization. As discussed above, this requires increased knowledge about cultural diversity, personal interactions with people from diverse backgrounds, and willingness to critically examine one’s assumptions. Another key is to anticipate difference and avoid calling attention to particular individuals.

Stereotype Threat and White Fragility

It’s important to avoid calling attention to particular individuals from diverse groups because of the risk of triggering concern over being stereotyped. An individual will not feel a sense of belonging if they experience a negative stereotype in the learning environment. Steele (1997) coined the term stereotype threat to describe risks that come from being perceived by others as fitting a negative stereotype. Success in school requires one to have a degree of identification with the learning environment. Academic self-authorship entails “forming a relationship between oneself and the domains of schooling such that one’s self-regard significantly depends on achievement in those domains” (Steele, 1997, p.616). Unfortunately the student who cares very much about succeeding in school is especially vulnerable to stereotype threat (Aronson, 2002). Other causes for vulnerability are strong identification with a group, consciousness of stigma, acceptance of a stereotype as having a kernel of truth, and belief that intelligence is fixed (Aronson, 2002). Risk of stereotype threat increases with desire to succeed, strong identification with a group, acceptance of a stereotype having a kernel of truth, and belief that intelligence is fixed. Highly competitive environments tend to increase the risk of stereotype threat. This may be especially true when individuals adopt a performance goal orientation, and especially when the goal is to perform so as to avoid demonstrating incompetence. According to Smith’s (2004) Stereotyped Task Engagement Model, adopting a performance-avoidance goal tends to undermine interest and engagement, which in turn harms performance. Identifying the causes for vulnerability to stereotype allows teachers to work to minimize the threat. For example, an intervention of three sessions on the malleability of intelligence has been found to have a significant impact on the academic achievement of Black college students (Aronson, Fried, & Good, 2002).

It is important to be aware of how stereotyping might undermine well-intentioned educational initiatives. Remedial or other special programs can backfire if the special treatment triggers stereotype threat in the students the programs are designed to help. For example, a program named “STEM research for women” may send the message that women are inherently bad at sciences and math and therefore are expected to need remediation. Steele (1997) offers these suggestions to help students who may be prone to experiencing stereotype threat:

- Express optimism about students’ potential

- Give challenging work

- Stress the expandability of intelligence

- Affirm explicitly that the students belong in the learning environment

- Value multiple perspectives

- Provide role models

Steele’s (1997) seminal work on stereotype threat offered a fresh perspective on the pervasive underachievement of Black high school students. Research on stereotype threat over the past twenty years has investigated the impacts of stigmatization on females, Latinos, older people, athletes, and LGBTQ individuals, among others. The breadth of applicability of stereotype threat emphasizes how stigmatization in any context is likely to harm individuals. Highly competitive environments tend to increase the risk of stereotype threat. This may be especially true when individuals adopt a performance goal orientation, and especially when the goal is to perform so as to avoid demonstrating incompetence (Smith, 2004). According to Smith’s (2004) Stereotyped Task Engagement Model, adopting a performance-avoidance goal tends to undermine interest and engagement, which in turn harms performance.

It is important to recognize that it is not only individuals with marginalized identities who feel threatened by discussions of difference. DiAngelo (2011) uses the term white fragility to describe common reactions of people from the culturally dominant group in the United States to interruptions in what is racially familiar to whites. Interruptions include being told that one has a racialized frame of reference, having one’s racial feelings challenged, being presented with evidence that access is unequal between racial groups, or encountering a person of color in a position of leadership (DiAngelo, 2011, p.57). Inability to directly confront assumptions that underlie white racial equilibrium can impede non-marginalized students from interacting, growing, and engaging with diverse educational environments. It is important to recognize and address white fragility, as otherwise it is too easy to view individuals with marginalized identities as “other,” i.e. thinking that “those people” are too sensitive. Critical thinking about race and privilege affects everyone, and no one is immune from emotional sensitivity to the cognitive dissonance that can arise from frank discourse about power and privilege.

Differentiated Instruction and Universal Design for Learning

Educational psychologists’ findings regarding diversity and inclusion form a convincing case for not merely tolerating diversity, but embracing and valuing it. So far we have addressed the cognitive and social benefits of diversity, means of creating an inclusive climate, and actions to minimize stereotyping. We will conclude with research-based ideas for embracing and valuing diversity in curriculum and instruction. These approaches are directly relevant to how librarians plan information literacy instruction and are relevant to the delivery of reference services.

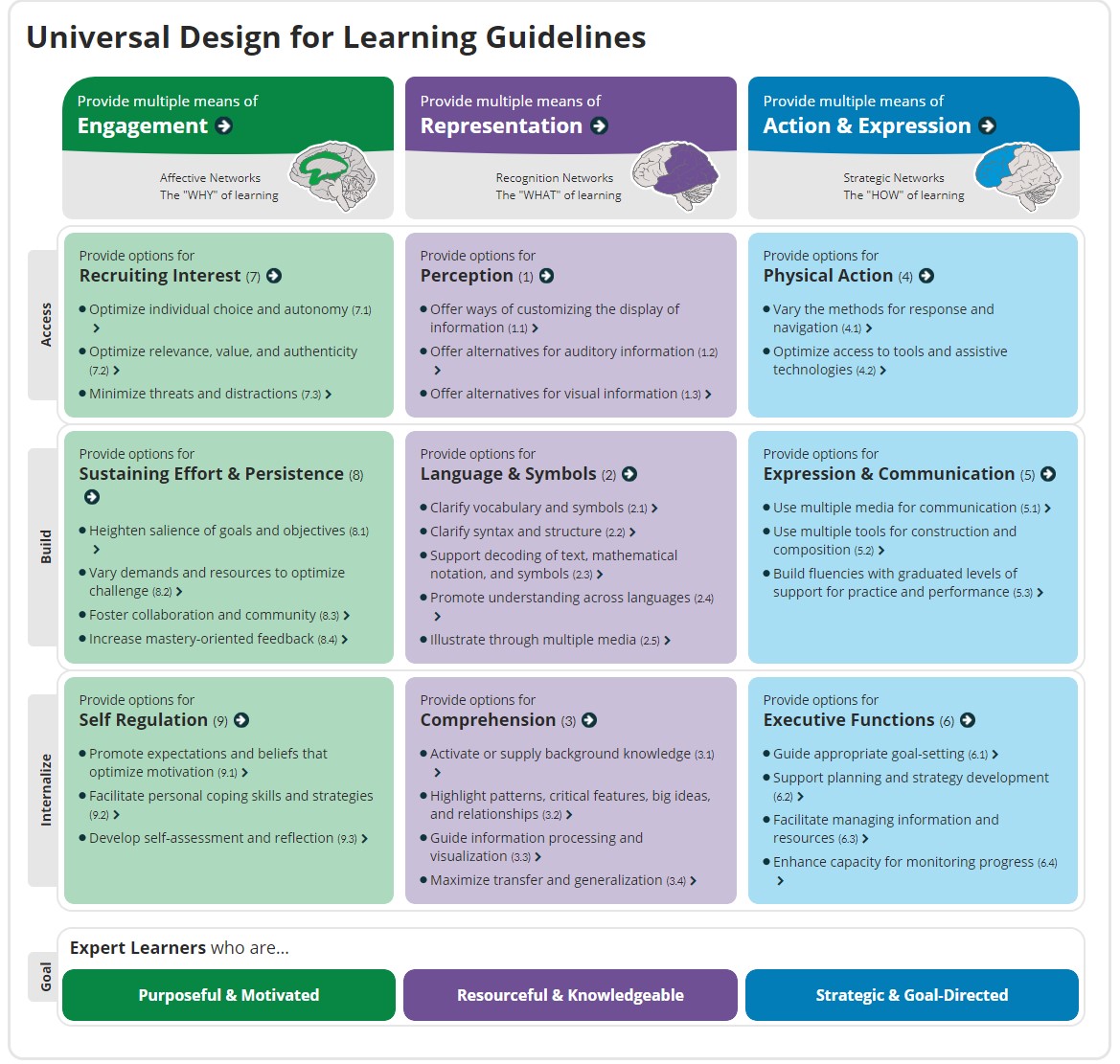

Two main themes for addressing the learning needs of diverse populations have emerged from the literature: differentiated instruction and universal design. Both are based on the premise that students should be given a range of choices of how to go about learning. Differentiated instruction means to provide students multiple ways to receive information and options for how to express what they have learned. Universal design for learning guidelines recommend providing multiple means of representation, action and expression, and engagement (Center for Applied Special Technology, 2011). The two approaches are very closely related. The primary difference between them is that differentiated instruction focuses on cultural differences whereas universal design is about how to plan a course of instruction with the flexibility to respond to various needs as they arise. Obviously the two are far from mutually exclusive, and in practice good teachers employ both to best meet students’ needs. Differentiated instruction focuses on cultural differences whereas universal design integrates flexible responses to needs as they arise. No teacher possesses a crystal ball that can predict which instructional techniques will work best with a particular group of students. Every experienced teacher knows there is always room for improvements in response to how well students are learning. Universal design for learning is intended to be flexible enough to accommodate multiple needs without overly disrupting the planned instruction.

A well-known version of differentiated instruction is the concept of “inviting all students to learn” (Dack & Tomlinson, 2015). Inviting all students to learn is premised on four recommendations:

- Recognize and appreciate cultural variance among your students

- Learn about and be aware of culturally influenced learning patterns

- Look beyond cultural patterns to see individuals

- Plan inviting instruction that is responsive to cultural difference and individual interests (Dack & Tomlinson, 2015).

The concept of inviting students to learn integrates five principles: affirmation, contribution, purpose, power, and challenge (Tomlinson, 2002). Effective teachers and librarians strive to connect educational goals with the personal interests of individual students. Affirming each person’s contributions and ability to rise to challenges helps make all students feel included and motivated to learn.

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is rooted in the conviction that minimizing barriers is preferable to devising individual accommodations. Planning ahead for how to minimize barriers can reduce the instructor’s workload and help remove stigma that may be attached to special treatment. A summary of the principles of universal design for learning are summarized in Figure 1 and available online at http://udlguidelines.cast.org/

Figure 1: Guidelines for Universal Design for Learning

The first principle is to provide multiple means of representation. That is, how is information being conveyed? This principle involves the recognition networks our minds use to gather and categorize information. UDL draws from neuroscientific evidence that the mind functions with three primary networks: affective, recognition, and strategic. The recognition network is responsible for perceiving information and transforming it into useful knowledge (National Center on Universal Design for Learning, 2014). Instructors should use both visual and auditory presentations whenever possible, and allow learners to adjust text size for visuals and volume for audio. The learner should be able to adjust the pace at which the information is conveyed. For example, offering a video capture of a presentation allows a student to review it later and pause, slow down, or repeat as needed. Students who need them should have access to assistive technologies, for example being allowed to use a tablet to take pictures of notes on a board and magnify them, or record a lecture for later review.

Providing flexible representations allows for individual variance in student abilities and enhances the engagement of all students. Linder (2016) found that 75% of students without disabilities said they used closed captioning and transcripts as a learning aid for four reasons: comprehension, accuracy, engagement, and retention. Sixty-six percent of students for whom English is a second language reported finding captions very or extremely helpful (Linder, 2016). These results demonstrate how incorporating universal design into the classroom helps more than just students with disabilities.

The second principle of universal design is to provide multiple means of action and expression. How are the students demonstrating what they have learned? Students can organize and express their ideas in a multitude of ways, for example composing a song or writing an essay. Some students test very well, while others require different environments to communicate the same information. Multiple means of expression can achieve the goal of validating what has been learned. Flexibility in the assignment might allow one student to express the functions of a cell with body movements, another to label a diagram, or another to write an essay.

The third principle is to provide multiple means of engagement, also referred to as the “why” of learning. This principle is about the affective side of learning, concerning how students get engaged, stay motivated, and are challenged appropriately. The question that comes from every level of education is “why”–why do I need to learn this? Why should I care? It is best to express learning goals and objectives from the start so students know the direction of learning. Upfront mutual understanding of goals builds trust. Creative instructors seek opportunities to insert choice into the course. For example, a research project could include a process for students to match their interests with the learning objectives of the project. Choice could be in degree of difficulty. Allowing choice in degree of difficulty accommodates a student motivated only by earning a credit as well as a student with a strong personal interest in the course content. Providing options for degree of engagement provides a choice for the students looking for ways to stretch themselves. An important aspect of UDL is to be aware of students’ emotional states. What interests and motivates one student can cause anxiety or stress for another. Being aware of students’ emotional states is important for identifying places they are getting stuck and in need of help.

For us, the really interesting thing about Universal Design for Learning is the incorporation of various scaffolding techniques to enhance critical thinking, goal-setting, and self-regulation. The National Center on Universal Design for Learning provides detailed explanations for each of the nine guidelines, complete with examples, resources, and citations to relevant research (National Center on Universal Design for Learning, 2014). A useful resource for anyone interested in implementing universal design in higher education is UDL on Campus (CAST, 2017). Incorporating the concepts of universal design can enhance learning for all students regardless of disability status. It is an excellent example of how understanding the findings from educational psychology can improve teaching and learning.

Takeaways for Librarians

- Present remedial elements of your information literacy program in ways that avoid singling out individuals or groups, because s. Separate sessions or exercises for remediation stigmatize the individuals assigned to them.

- If you use group work, try to arrange groups to have diverse members.

- Incorporate diverse perspectives in reference and instruction, and don’t shy from making students engage with ideas that unsettle them.

- Remember that your interactions with students are part of the process of developing intercultural maturity (theirs and yours!).

- Reassure students that they belong in the library and they deserve to be there.

- When a student seems unsure, point out that everyone feels out of place sometimes, and they’re not alone.

- Consider inviting trained inter-group dialogue facilitators to conduct sessions in your library, and participate yourself.

- Be intentional about building your own cultural fluency by learning about other cultures and interacting with individuals different from yourself. Be brave and step out of your comfort zone.

- Advocate for and work toward a library and a campus-wide climate that values and supports diversity.

- Avoid singling out any group for special treatment.

- Find ways to incorporate Universal Design for Learning in your instruction program and throughout the library’s physical and virtual presence.

Recommended Reading

Aronson, J. (2002). Stereotype threat: Contending and coping with unnerving expectations. In J. Aronson (Ed.), Improving academic achievement (pp. 279-301). San Diego, CA, US: Academic Press. doi:10.1016/B978-012064455-1/50017-8

Joshua Aronson’s extensive research on stereotype threat is condensed in this overview of his and others’ findings. Topics include who is vulnerable to stereotype threat, ways of coping with it, and what teachers can do to reduce it. The people most prone to stereotype threat are those who care very much about succeeding in a domain but are keenly aware of stigma attached to their group. Unfortunate coping strategies include self-handicapping, avoiding challenge, suppressing oneself, and divesting self-esteem from the learning environment. To reduce the risk of those behaviors, teachers can emphasize that ability improves with effort and manage classes to maximize opportunities for interactions among diverse students.

Bowman, N. A. (2010). College diversity experiences and cognitive development: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 80(1), 4-33. doi:10.3102/0034654309352495

Nicholas Bowman’s study is based on the premise that diversity experiences in college cause students to experience disequilibrium, which forces them to rethink previous views and grow intellectually. Twenty-three studies were analyzed to gauge the impact of diversity on cognitive growth. The author concluded that there is a small but significant relationship. The strongest relationship between racial diversity and cognitive development was due to interpersonal relationships. Diversity workshops and diversity courses also show a significant relationship. Bowman acknowledges that many studies failed to control for other variables that contribute to cognitive development, but nevertheless concludes that existing studies make clear the value of interpersonal experiences and a campus climate conducive to racial contact and dialogue.

Center for Applied Special Technology. (2011). Universal design for learning guidelines. Retrieved from http://www.udlcenter.org/sites/udlcenter.org/files/updateguidelines2_0.pdf

The principles of universal design for learning are distilled to a single page. The fundamental principles are to provide multiple means of representation, expression, and engagement. The desired outcomes are to have resourceful, knowledgeable learners who are strategic, goal-directed, and purposeful. Offering both visual and auditory access to information is key, but universal design also includes goal setting, training in self-regulation, and critical thinking skills. In addition to the details at http://www.udlcenter.org/aboutudl/udlguidelines, the http://www.cast.org/ site contains a wealth of additional information about universal design for learning.

Dack, H., & Tomlinson, C. A. (2015). Inviting all students to learn. Educational Leadership, 72(6), 10-15.

Carol Ann Tomlinson is a leading educational psychologist on the topic of differentiated learning. Her advocacy for perspective on matching teaching techniques to student characteristics is based grounded on the premise that excellent teachers are students of their students. Teachers should he principles espoused here are to recognize and appreciate cultural difference, look for culturally influenced learning patterns, see individuals for who they are, and plan inviting instruction. Inviting instruction gives students a degree of choice in how to achieve learning objectives. Students should be allowed to share their own perspectives in the context of the course material.

Ford, K. A., & Malaney, V. M. (2012). ‘I now harbor more pride in my race’: The educational benefits of inter– and intra–racial dialogues on the experiences of students of color and multiracial students. Equity & Excellence in Education, 45(1), 14-35. doi:10.1080/10665684.2012.643180

Kristie Ford and Victoria Malaney describe the benefits of the social justice practice of intergroup dialogue for people of color. The distinct components of intergroup dialogue are structured interaction and active, and engaged learning lead by a trained facilitator. Racial identity is typically developed through a progression from conformity to dissonance to immersion to internalization and finally integrative awareness. The authors conclude that intergroup dialogue significantly helps students of color break their silence and move toward healthy integrative awareness of their racial identities. Historically white institutions can be more welcoming to students from ethnic minorities if they provide more opportunities for interaction within and across identity groups.

Gurin, P., Dey, E. L., Hurtado, S., & Gurin, G. (2002). Diversity and higher education: Theory and impact on educational outcomes. Harvard Educational Review, 72(3), 330-366. doi:10.17763/haer.72.3.01151786u134n051

Patricia Gurin was an expert witness in collaboration with Sylvia Hurtado, Eric Dey, and Gerald Gurin in the University of Michigan’s defense of its affirmative action admissions policies. The policies were rescinded by a Michigan constitutional amendment that was upheld by the Supreme Court. Despite that outcome, this paper is valuable for its summary of the evidence that cultural diversity on a college campus enhances students’ learning. A key point is that white students benefit from interactions with diverse peers because experiences in and out of class enhance lead to greater active critical thinking.

Gurin, P., Nagda, B. A., & Zúñiga, X. (2013). Dialogue across difference: Practice, theory and research on intergroup dialogue. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Establishing genuine dialogue across cultural difference is challenging, so this roadmap for how to facilitate dialogue that is most welcome. The program has four stages: forming and building relationships, exploring differences and commonalities, talking about hot topics, and planning action and collaboration. A key component is engagement with sensitive issues such as interracial relationships, self-segregation on campus, racial profiling, and immigration. This book includes research results on the positive effects of intergroup dialogue. Students who engage in intergroup dialogue gain better understanding of others, are more empathetic, have more intercultural interaction, reach out more to people different from themselves, and place greater value on diversity.

Kimball, E. W., Wells, R. S., Ostiguy, B. J., Manly, C. A., & Lauterback, A. A. (2016). Students with disabilities in higher education: A review of the literature and an agenda for future research. In M. B. Paulsen (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (31st ed., pp. 91-156), New York: Springer.

As the title of this book chapter indicates, the authors provide an overview of major themes and issues surrounding students with disabilities. It includes succinct summaries of relevant legislation and court decisions, how disabilities are defined, stigma, support services, learning outcomes, and current research paradigms. Almost twenty-eight percent of college freshman have some type of physical or emotional disability. The broad coverage and extensive bibliography make this an excellent entry point to the literature on students with disabilities in higher education.

Museus, S. D. (2011). Generating ethnic minority student success (GEMS): A qualitative analysis of high-performing institutions. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 4(3), 147-162. doi:10.1037/a0022355

Samuel Museus investigates the characteristics of the historically white colleges that have successfully diversified their campuses. SThe main themes are that successful colleges provide networks of communication and collaboration, are committed to supporting students of diversity, humanize the educational experience, and have an ethos of institutional responsibility for integrating diverse students into the life of the campus. The author emphasizes that efforts to change a campus culture must be holistic. All four themes must be addressed to create an environment geared to minority students’ success and feeling at home in college.

Steele, C. M. (1997). A threat in the air: How stereotypes shape intellectual identity and performance. American Psychologist, 52(6), 613-629. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.52.6.613

Claude Steele introduced the term stereotype threat to describe the fear of being reduced in the perceptions of others to a negative stereotype. He makes the case that the persistent achievement gap between black and white students is due in part to stereotype threat. The evidence is based on a series of studies including one with white women taking a math test and another with Black students taking standardized tests. Steele concluded that stereotype threat causes affected groups to dissociate self-esteem from school achievement. Remediation is likely to backfire if students perceive the remedial work as reinforcing a negative stereotype.

Works Cited

Allen, J., Bower, A., & Miller, H. (2004). Three teaching strategies for developing intercultural understanding of pre-service teachers in an educational psychology course. Journal of Teacher Researcher (Tutkiva Opettaja), 10(1), 128–137.

Aronson, J. (2002). Stereotype threat: Contending and coping with unnerving expectations. In J. Aronson (Ed.), Improving academic achievement: Impact of psychological factors on education (pp. 279–301). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. doi:10.1016/B978-012064455-1/50017-8

Aronson, J., Fried, C. B., & Good, C. (2002). Reducing the effects of stereotype threat on African American college students by shaping theories of intelligence. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 38(2), 113–125. doi:10.1006/jesp.2001.1491

Bandura, A. (1989). Human agency in social cognitive theory. American Psychologist, 44(9), 1175–1184. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.44.9.1175

Bowman, N. A. (2010). College diversity experiences and cognitive development: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 80(1), 4–33. doi:10.3102/0034654309352495

Brown, L. M., & Dobbins, H. (2004). Students of color and European American students’ stigma-relevant perceptions of university instructors. Journal of Social Issues, 60(1), 157–174. doi:10.1111/j.0022-4537.2004.00104.x

CAST. (2017). UDL on Campus: Universal Design for Learning in Higher Education. Retrieved from http://udloncampus.cast.org

CAST (2018). Universal design for learning guidelines version 2.2 [graphic organizer].Wakefield, MA: Author.

Center for Applied Special Technology. (2011). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines. Retrieved from http://www.udlcenter.org/sites/udlcenter.org/files/updateguidelines2_0.pdf

Dack, H., & Tomlinson, C. A. (2015). Inviting all students to learn. Educational Leadership, 72(6), 10–15.

DiAngelo, R. (2011). White fragility. International Journal of Critical Pedagogy, 3(3), 54–70.

Erikson, E. H. (1980). Identity and the life cycle. New York, NY: Norton.

Fleming, A. R., Oertle, K. M., Plotner, A. J., & Hakun, J. G. (2017). Influence of social factors on student satisfaction among college students with disabilities. Journal of College Student Development, 58(2), 215. doi:/10.1353/csd.2017.0016

Gurin, P., Dey, E. L., Hurtado, S., & Gurin, G. (2002). Diversity and higher education: Theory and impact on educational outcomes. Harvard Educational Review, 72(3), 330–366. doi:10.17763/haer.72.3.01151786u134n051

Gurin, P., Nagda, B. A., & Zúñiga, X. (2013). Dialogue across difference: Practice, theory and research on intergroup dialogue. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Kegan, R. (1994). In over our heads: The mental demands of modern life. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Linder, K. (2016). Student uses and perceptions of closed captions and transcripts: Results from a national study. Retrieved from https://www.3playmedia.com/resources/industry-studies/student-uses-of-closed-captions-and-transcripts/

Museus, S. D. (2011). Generating ethnic minority student success (GEMS): A qualitative analysis of high-performing institutions. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 4(3), 147–162. doi:10.1037/a0022355

National Center on Universal Design for Learning. (2014). UDL Guidelines–Version 2.0. Retrieved from http://www.udlcenter.org/aboutudl/udlguidelines

Palmer, C., & Roessler, R. T. (2000). Requesting classroom accommodations: Self-advocacy and conflict resolution training for college students with disabilities. Journal of Rehabilitation, 66(3), 38–43.

Pascarella, E. T., Martin, G. L., Hanson, J. M., Trolian, T. L., Gillig, B., & Blaich, C. (2014). Effects of diversity experiences on critical thinking skills over 4 years of college. Journal of College Student Development, 55(1), 86–92. doi:10.1353/csd.2014.0009

Perez, R. J., Shim, W., King, P. M., & Baxter Magolda, M. B. (2015). Refining King and Baxter Magolda’s model of intercultural maturity. Journal of College Student Development, 56(8), 759–776. doi:10.1353/csd.2015.0085

Smith, J. L. (2004). Understanding the process of stereotype threat: A review of mediational variables and new performance goal directions. Educational Psychology Review, 16(3), 177–206. doi:10.1023/B:EDPR.0000034020.20317.89

Steele, C. M. (1997). A threat in the air: How stereotypes shape intellectual identity and performance. American Psychologist, 52(6), 613–629. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.52.6.613

Stephens, N. M., Brannon, T. N., Markus, H. R., & Nelson, J. E. (2015). Feeling at home in college: Fortifying school-relevant selves to reduce social class disparities in higher education. Social Issues and Policy Review, 9(1), 1–24. doi:10.1111/sipr.12008

Tomlinson, C. A. (2002). Invitations to learn. Educational Leadership, 60(1), 6–10.

Walton, G. M., & Cohen, G. L. (2007). A question of belonging: Race, social fit, and achievement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(1), 82–96. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.92.1.82

Zúñiga, X., Lopez, G. E., & Ford, K. A. (2014). Intergroup dialogue: Engaging difference, social identities and social justice. London, England: Routledge.