This chapter was originally published as Black, S., & Allen, J. D. (2017). Insights from educational psychology part 1: Foster intrinsic motivation. The Reference Librarian, 58(1), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763877.2016.1200515. Minor revisions have been made from the version published in Reference Librarian.

Personal interest and desire to learn are primary drivers of educational attainment. An intrinsically motivated student can be expected to learn more and retain what they have learned better than a student forced against their will to complete a task. Intrinsic motivation is thus an engine that drives effective learning. But what is intrinsic motivation, and how can it be fostered? Intrinsic motivation has been characterized by Ryan and Deci (2000) as behaviors “freely engaged out of interest without the necessity of separable consequences (p. 233)” It is doing something for the enjoyment or enrichment one inherently gains from partaking in the activity. Levels of intrinsic learning can be measured by degrees of interest, engagement, and exploration.

Interest and motivation

Over a century ago John Dewey argued that educators should make things interesting by empowering students to recognize how learning relates to their experience, powers, and needs (Dewey, 1913). He asserted that if someone recognizes the utility of the object of learning as a means to develop and attain a desirable goal, they will naturally be interested and exert effort. Proper education therefore should provide environments designed to induce personal development. Dewey argued that it is a mistake to force students to complete tasks through sheer effort, because their minds will inevitably wander and nothing lasting will be learned. He also argued that it is a mistake to “make things interesting” through entertainment. Attempts to attract attention to a lesson with no connection with a desired end are counterproductive. Entertaining embellishments do not support learning unless they contribute to personal development. According to Dewey, genuine interest arises from a person identifying with a course of action. It only works to present a student with a difficult challenge when doing so stimulates increased depth and scope of thinking (Dewey, 1913).

Interest can be individual or situational. Individual interest is often based on a student’s prior knowledge or experiences, and can be fostered by allowing students to apply their curiosity to personally relevant topics. Situational interest can be enhanced by presenting information coherently, vividly, and with interesting details (Brophy, 2004). But as Dewey cautioned long ago, details inserted merely to entice rather to inform can distract from genuine learning. Librarians can play an important role in helping students identify their academic interests, needs and goals, and help them develop the strategies to achieve them. The RUSA Guidelines for Behavioral Performance (RUSA, 2008) specify that librarians should express interest, listen carefully, help students refine their research questions, and work with them to develop an effective search. The reference interview process is filled with opportunities to help students find connections between the research topic and their own personal interests.

Engagement in learning is due in part to a person’s level of interest or curiosity. If someone is already interested in a topic, they are naturally likely to engage in learning more about it. In fact research has found that high levels of interest have positive effects on grades, study habits, and reading comprehension (Silvia, 2012). Curiosity can be regarded as openness to novelty. A curious person is drawn to the new and different, and is open to novel experiences. Openness leads to engagement, which then leads to achievement (Silvia, 2012). The epitome of engagement has been described as “flow,” a state characterized by intense concentration, merging of action and awareness, loss of self-awareness in the context, and seemingly rapid passage of time (Nakamura & Csikszentmihalyi, 2002). Csikszentmihalyi’s work on flow grew out of his interest in intrinsic motivation, particularly what led people to engage in “autotelic” (auto=self, telos=goal) activities. The epitome of engagement has been described as “flow,” a state characterized by intense concentration, merging of action and awareness, loss of self-awareness in the context, and seemingly rapid passage of time. He found that flow happens in situations where people experience an optimal level of challenge for their personal skill level and have clear, immediate goals and feedback. But before optimal levels of engagement can be attained, one must first develop an interest in the topic or activity. As academic skills develop through instructional support and guidance by the librarian/teacher, the student develops a greater sense of self-efficacy and increased ability to take on greater academic challenges.

Phases of interest development

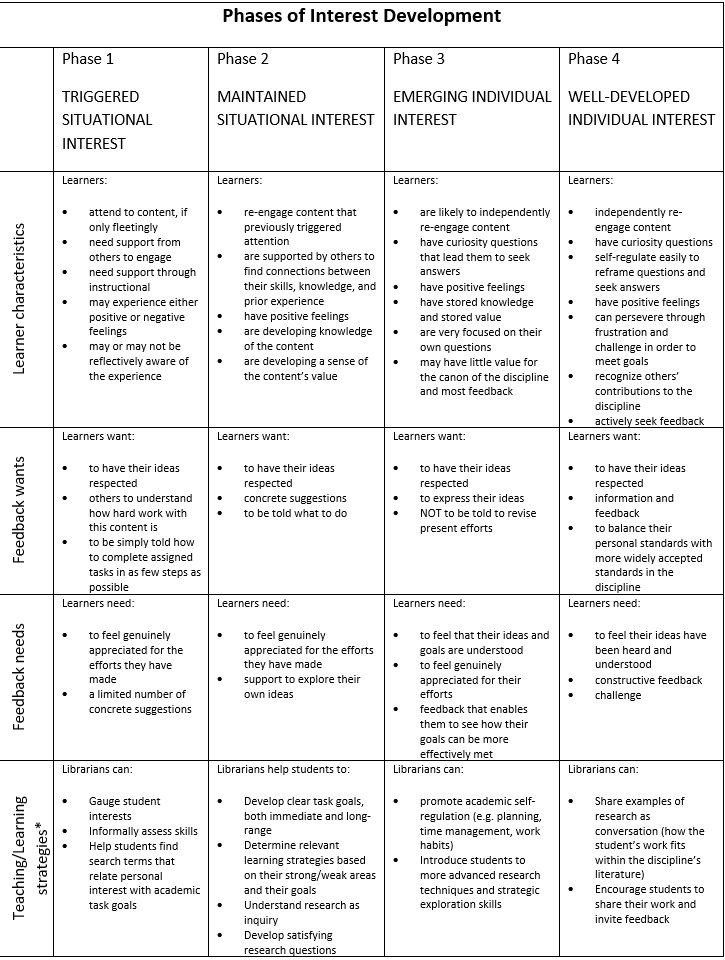

Exploration fosters intrinsic motivation when the research topic captures the interest or curiosity of the student. Psychologists identify two types of interest, situational or individual. Situational interest is liking or being drawn to something may happen in a particular time or place. Individual interest is extended over time as a continued area of pursuit. Krapp (1999) described how interest is the result of person-object relationships in specific situations. That is, the characteristics of the person interact with the learning context to create a psychological state of “interestingness” within the person. Renninger (2009) described interest development as a four phase process: triggered situational interest, maintained situational interest, emerging individual interest, and well-developed individual interest. In each phase, learners have different wants and needs for feedback. For example, a student newly exposed to a situation in which interest is initially triggered needs expressions of appreciation for the effort expended so far, and just a few concrete suggestions for what to do next. A student beginning to develop sustained individual interest needs not only appreciation, but also affirmation of their ideas and constructive feedback. Only at the final phase of well-developed individual interest is a student really ready to be challenged and introduced to the standards of a discipline (Renninger, 2009). A summary of learners’ characteristics, feedback needs and feedback wants at the four stages of development is depicted in Table 1. The table is based on Renninger (2009), but we have added a fourth row of teaching/learning strategies for librarians.

Table 1: Phases of Interest Development

As teachers, librarians should help students develop learning strategies they can use independently. Students’ abilities to self-regulate should grow with their developing interests. As a student transitions or develops from the initial phase of triggered situational interest to well-developed individual interest, they of necessity develop the qualities that make them a stronger academically self-regulated learner. Self-regulation is a concept of major importance in educational psychology and will be the focus of Chapter 2.

Renninger’s (2009) work focused on students in elementary and high school. But the four phases clearly repeat for many college students, particularly within a general education curriculum designed to introduce them to new disciplines and modes of thinking. A student being exposed for the first time to the content and modes of inquiry in an unfamiliar discipline is in particular need of support, understanding, and concrete suggestions. Only after situational interest has developed into individual interest will a student be willing and able to actively seek feedback, have their efforts be challenged, and be ready to learn the standards of the discipline.

Self-determination Theory

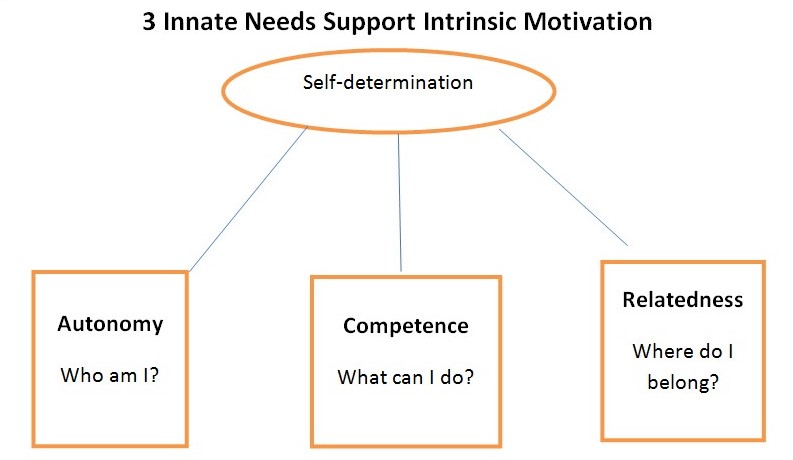

Self-determination theory asserts that human motivation operates within the context of innate psychological needs for competence, autonomy, and social relatedness. A social context that supports those fundamental needs will maintain or enhance intrinsic motivation. Conversely, an environment that frustrates individual’s ability to develop competence, autonomy and relatedness undermines intrinsic motivation (Deci & Ryan, 2000). Extensive research on the self-determination of behavior indicates that an environment that fosters intrinsic motivation is supportive of overall psychological health and well-being. Many educational psychologists have explored how to support students’ autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Main themes to emerge from the application of self-determination theory to learning environments are the need to avoid controlling language, the benefits of providing students some choices (but not too many), and the importance of providing enough supports to enable students to feel competent as they are challenged with new tasks.

Figure 1: Self-determination Theory and Intrinsic Motivation

The language an instructor uses can foster or inhibit an autonomy supportive learning environment. As described by self-determination theory, autonomy is students’ perceived degree of having choices and feelings of ownership. An autonomy-supportive learning environment accounts for students’ individual needs and interests. The benefits of an autonomy-supportive environment are well established. Studies have positively linked student autonomy with their enjoyment of learning, feelings of competence, engagement, intrinsic motivation, academic achievement, and persistence (Young-Jones, Cara, & Levesque-Bristol, 2014). Even brief messages of support can enhance the learning environment. Supportive language “includes words like consider, suggest, encourage, invite, and phrases such as this will help you by, the reason for this is, and thank you for sharing your concern” (Young-Jones, Cara, and Levesque-Bristol, 2014). If prescriptive language like “must,” “have to,” or “required” are necessary, they should be accompanied with an opportunity for students to ask questions or voice concerns. This relates back to the feedback wants described in Renninger’s (2009) Four Phases of Interest Development.

One of the most effective ways to support feelings of competence is to present learners with just the right amount of choice and challenge. Competence is closely tied to a student’s belief that they can effectively match their current skills with the academic challenge placed before them. Providing choices can have the positive effect of letting a student match a task to their personal interests, thereby increasing the odds that the student will be intrinsically motivated to complete the task. But Brophy (2004) suggests caveats to the assumption that more choice is always good. First, just because a student feels more positively about a task does not always translate into better academic performance. Second, the choices offered may not connect with a student’s interests. Third, too many choices can be confusing, especially for younger learners. Finally, Brophy (2004) asserts that not all students desire to make choices individually, because some may prefer options to be chosen as a group.

Challenges need to be appropriately scaled and timed. As Renninger (2009) implied in the Four Phases of Interest Development, presenting too much challenge too early to a student is likely to discourage further interest and engagement. It is better to provide a learning environment whereby students experience success early on, then later presented with progressively more challenging material. The early successes and measured increases in challenge promote feelings of competence.

Adequate instructional supports need to be provided to students to foster a sense of relatedness to the librarian and learning environment. The most fundamental way to do this is to genuinely listen to students, be respectful of their ideas, and encourage their individual success. Educational psychologists have extensively studied the effects of cooperative learning on sense of relatedness and academic achievement. So much so, in fact, that the topic of responding to students’ need for relatedness will be reserved for Chapter 5, Learning is a Social Act.

Feedback, praise, and motivation

Feedback can play an important role in fostering intrinsic motivation. One common type of feedback is to praise someone on how smart they are, on the logic that if a person feels smart they will be motivated to learn. It turns out, however, that praise and feedback are only motivating if employed correctly. The wrong kinds of praise and feedback can actually undermine motivation. Brophy (1981) explains that praise is different from feedback in that praise commends the worth of an action and includes an expression of approval or admiration. Feedback can simply be an affirmation of a correct response that serves the useful purpose of providing knowledge of results. Praise includes an expression of value or status, usually conveyed with a measure of surprise, delight, or excitement (Brophy, 1981). Properly administered praise is capable of reinforcing desired behaviors. But to serve as reinforcement for positive behaviors like high quality academic work or cooperative social interaction, the praise must be contingent on performance of the behavior to be reinforced, specify the particulars of the behavior, and be sincere and credible. Brophy’s (1981) list of guidelines for effective praise are depicted in Table 2.

Table 2: Guidelines for Effective Praise

| Effective praise | Ineffective praise |

| 1. Is delivered contingently | 1. Is delivered randomly or unsystematically |

| 2. Specifies the particulars of the accomplishment | 2. Is restricted to global positive reactions |

| 3. Show spontaneity, variety, and other signs of credibility; suggests clear attention to the student’s accomplishment | 3. Shows a bland uniformity, which suggests a conditioned response made with minimal attention |

| 4. Rewards attainment of specified performance criteria (which can include effort criteria) | 4. Rewards mere participation, without consideration of performance processes or outcomes |

| 5. Provides information to students about their competence or the value of their accomplishments | 5. Provides no information at all or gives students information about their status |

| 6. Orients students toward better appreciation of their own task-related behavior and thinking about problem solving | 6. Orients students toward comparing themselves with others and thinking about competing |

| 7. Uses students’ own prior accomplishments as the context for describing present accomplishments | 7. Uses the accomplishments of peers as the context for describing students’ present accomplishments |

| 8. Is given in recognition of noteworthy effort or success at difficult (for this student) tasks | 8. Is given without regard to the effort expended or the meaning of the accomplishment (for this student) |

| 9. Attributes success to effort and ability, implying that similar successes can be expected in the future | 9. Attributes success to ability alone or to external factors such as luck or easy task |

| 10. Fosters endogenous attributions (students believe they expend effort on the task because they enjoy the task and/or want to develop task-relevant skills) | 10. Fosters exogenous attributions (students believe that they expend effort on the task for external reasons–to please the teacher, win a competition or reward, etc. |

| 11. Focuses students’ attention on their own task-relevant behavior | 11. Focuses students’ attention on the teacher as an external authority figure who is manipulating them |

| 12. Fosters appreciation of and desirable attributions about task relevant behavior after the process is complete | 12. Intrudes into the ongoing process, distracting attention from task relevant behavior |

As indicated in the guidelines for effective praise listed in Table 2, Brophy (1981) also paid considerable attention to the role of attribution on the effect of praise. Attribution theory focuses on “the causal attributions that people make in achievement situations—the explanations we generate to explain our behavior” (Brophy, 2004, p.61). Several educational psychologists in the 1980’s and 1990’s explored the interrelationship of praise and attributions. A notable finding was that praise for being smart may cause students to attribute success to static ability (Mueller & Dweck, 1998). Such praise could have the unintended consequence of discouraging effort by leading a student to think “I’m just no good at this, so there’s no use trying.” Attribution theory focuses on explanations we generate to explain our behavior

Mueller and Dweck (1998) explored how praise for intelligence can undermine motivation. The reason, they found, is that a child told they’re smart may shift his or her focus to appearing smart relative to others. A need to appear smart can cause them to dwell on performing well instead of challenging themselves to learn to the best of their ability. When performance takes precedence over challenge, students tend to avoid learning to their full capability. Performance goals thus tend to limit achievement of high performing students and be very demotivating to students who perform poorly relative to peers. Mueller and Dweck (1998) found that praise for effort or work strategies is a more effective way to promote motivation and performance. Students at any achievement level benefit from believing that effort is key to success.

Research on attribution theory suggests that academic success must be seen by students as an interaction between one’s abilities and one’s efforts (Weiner, 2010). Students must have the necessary content knowledge, academic skills and effective learning strategies to succeed academically. But students must also be able to adjust their level of effort to match the level of difficulty, demands, and challenge of the academic task. Thus, the more academically able a student is, the less effort they need to expend to achieve success relative to the effort a student with less academic ability. Conversely, a student with less ability in an academic area must apply more (or more effective) efforts to achieve the same level of success as someone with higher abilities. In addition, as one develops greater abilities in an area, they are likely to seek higher academic challenges. The experience of building abilities and experiencing success teaches them they can control and adjust their efforts to match the level of challenge. Students who lack necessary abilities and are not taught how to develop requisite academic skills and effective learning strategies will fail to succeed. As they continue to fall short of success their motivation will decrease in reaction to the ineffectiveness of their efforts. This downward spiral of effort and success is one form of what has been called an exacerbation cycle (Storms & McCaul, 1976). Techniques for helping students avoid getting trapped in an exacerbation cycle are discussed in Chapter 12: Interventions and Collaborations.

So how do librarians encourage students to believe that effort is important? Empower them with the research skills and effective learning strategies necessary for academic success. The role of teachers and librarians is thus not to just inform students that effort is important, but to provide them the academic knowledge, skills and strategies that will allow their efforts to be successful. After the students have expended effort it is important that they reflect on how their improved knowledge, skills and strategies influenced the effectiveness of their efforts.

The cycle of success that can occur when students are enabled to have effort result in achievement will be explored further in Chapter 2, in which we investigate the important roles of self-efficacy, self-regulation, goal setting and mindset on academic success.

Takeaways for Librarians

- Continue our traditional job of developing collections and providing services that support the broad range of our patrons’ interests.

- Tie instruction to students’ personal interests whenever possible.

- Promote reference service as a means to support students’ ability to develop competence in library research.

- Encourage students to try things on their own, while still making it clear that support is available if needed.

- Strive to present students just the right amount of challenge to stretch their skills, neither leaving them bored nor feeling overwhelmed.

- Encourage students to relate their research experiences with peers, professors, librarians, and family.

- When marketing reference and instruction, pay heed to students’ innate needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Avoid wording that might send the message that students are dependent or incompetent, and emphasize the benefits of forming a relationship with librarians.

- Tailor help and feedback to the appropriate phase of interest development, to wit:

- For learners just beginning to be interested in a problem or project, express appreciation for the effort they’re making and offer only a select few concrete suggestions for how to proceed,

- For learners maintaining an interest in a problem or project, offer more extensive support, a fuller array of concrete suggestions, and encourage them to explore their own ideas,

- For learners with an emerging individual interest in a topic, avoid asking them to revise current efforts, but instead give feedback for how to more effectively meet their goals,

- For those with a well-developed personal interest, first take care to respectfully listen, then offer constructive feedback and challenges to research more broadly and deeply.

- Provide praise that is tied directly to the patron’s action or performance, base instructive comments on what they have tangibly produced or that you directly observed them accomplish.

- Be sure your praise or feedback is specific, avoid empty gestures like “great job” without giving details about what made the job great.

- Provide supportive, but specific, criticism of weaknesses that need to be addressed and describe the skills, strategies, and additional resources that might help students strengthen their weak areas.

- Fake praise will send the wrong message. Be genuine and spontaneous to make it clear your praise is based on a thoughtful and accurate assessment of the person’s accomplishments.

- Praise students for their efforts and strategies as well as their abilities. For example say “the strategy you used to approach this problem was very effective and allowed you to demonstrate your understanding” rather than “you’re very smart.”

- Feedback need not be expressed as praise. The main educational benefit of feedback comes from providing concrete, actionable information about the learner’s processes and strategies.

Recommended Reading

Brophy, J. (1981). Teacher praise: A functional analysis. Review of Educational Research, 51(1), 5-32. doi:10.2307/1170249

Jere Brophy combined a review of existing studies with his own ongoing classroom-based research to describe the characteristics of effective praise. The main points are that in order to effectively reinforce desired behaviors, praise must be contingent, specific, and credible. He described that praise can serve many functions besides being a way for teachers to consciously reinforce behavior. The other functions of praise include spontaneous expressions of surprise, to balance prior criticism, send a message to other students in the class, offer peace, respond to requests for positive feedback, create a transition from one activity to the next, or give encouragement.

Brophy, J. (2004). Motivating students to learn (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Brophy’s highly readable overview of how to apply educational research findings to the practice of teaching has long been a standard textbook in teacher education programs. This, the second edition, includes chapters on self-determination theory (Ch. 7) and other ways to support intrinsic motivation (Ch. 8). The book is filled with practical suggestions for teachers, many of which are applicable to librarianship in higher education.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The ‘what’ and ‘why’ of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227-268. doi:10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

This 42-page overview of self-determination theory has been cited within PsycINFO over 2,800 times. Edward Deci and Richard Ryan review the research on self-determination and goal pursuits across a broad range of human experience. As a consequence this article’s scope extends beyond educational psychology. Nevertheless it provides an authoritative overview of self-determination theory and its role in motivation. The core of the theory is that all people have innate desires for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. This article is one among dozens of works by Deci and Ryan on motivation and self-determination. A book-length version is their 1985 Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior.

Dewey, J. (1913). Interest and effort in education. Boston, MA, US: Houghton Mifflin Company. doi:10.1037/14633-000

John Dewey, Professor of Philosophy at Columbia University, wrote this slim volume in part to oppose what he saw as two common errors educators make regarding “making things interesting.” The first error is to emphasize effort as an exercise in self-discipline. Such forced effort teaches students to appear to comply, but their minds will inevitably wander and little will be learned. The second error is to make learning amusing and stimulating without attending to how the activity will contribute to personal development. Students will be interested and exert effort when they see for themselves how the learning is a means to a desired end.

Krapp, A. (1999). Interest, motivation and learning: An educational-psychological perspective. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 14(1), 23-40. doi:10.1007/BF03173109

Andreas Krapp summarizes research on interest published in the second half of the 20th century. Interest is viewed as the interaction of person with object. Such situational interest is distinct from arousal or curiosity. However, a person can have a preexisting disposition to being interested in a thing, topic, idea, or discipline. Individual interest can positively influence academic achievement and reading comprehension. A person will develop sustained interest if they assess the object of interest as sufficiently important and if engagement with it is emotionally rewarding.

Mueller, C. M., & Dweck, C. S. (1998). Praise for intelligence can undermine children’s motivation and performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(1), 33-52. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.75.1.33

Claudia Mueller and Carol Dweck examined the popular notion that praising children for ability will motivate them to learn. But based on five interrelated studies, they concluded that praise for intelligence or ability can have the negative effect of turning the praised students away from “being challenged” and “learning a lot” to focusing on “seeming smart.” Praise for ability may also lead students to think that ability is static, and that failure is due to personality characteristics that cannot be changed. Perhaps most damaging of all is that if a student accustomed to being told how capable they are suffers a setback, they may give up rather than showing resilience in the face of challenge. Dweck’s research on learned helplessness, the effects of praise, performance versus mastery goals, and mindset spans from the 1970’s to the present.

Nakamura, J. and Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2002). The concept of flow. In C. R. Snyder, S. J. Lopez, C. R. Snyder, S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 89-105). New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press.

The concept of flow was originally published in Beyond Boredom and Anxiety (Jossey-Bass, 1975). In that and later works, Mihalyi Csikszentmihalyi describes the conditions and circumstances within which individuals become totally immersed in an activity. Rock climbers, musicians, chess players and others experience subjective states of “flow.” Flow only occurs when a challenge stretches one’s existing skills within personal capacities, and there are clear and immediate goals and feedback. Since flow experiences arise via interactions between individuals and their environment, motivation emerges out of the challenges, goals, and feedback experienced in the activity. Teachers can foster flow by challenging students to stretch their skills and by providing support as needed.

Renninger, K. A. (2009). Interest and identity development in instruction: An inductive model. Educational Psychologist, 44(2), 105-118. doi:10.1080/00461520902832392

Renninger presents her Phases of Interest Development model as one that is based on evidence but needs to be tested to be refined. As such, the phases of interest development are intended to help researchers formulate hypotheses. Interest is based on “triggers” capable of shifting learners’ thinking due to surprise, novelty, unexpected complexity or cognitive dissonance. Renninger’s “triggers” are distinct from “threshold concepts” in that triggers can be reversed if one loses interest over time. The four phases of interest are 1) triggered situational interest, 2) maintained situational interest, 3) emerging individual interest and 4) well-developed individual interest. Learners in any phase appreciate having their efforts acknowledged and respected, but those whose interests are just emerging should be given fewer, more carefully selected suggestions for how to proceed.

Silvia, P. J. (2012). Curiosity and motivation. In R. Ryan (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of human motivation. Oxford handbooks online. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195399820.013.0010

Silva summarizes three major lines of thought regarding the role of curiosity and motivation in learning and human behavior. One approach to curiosity has been to describe it as a way to reduce negative feelings such as uncertainty or unhappiness with an information gap. Others have explored curiosity as a driver of intrinsic motivation. The third major perspective on curiosity has been to view it as a fairly stable personality trait that partially explains levels of personal achievement. Silva concludes with main directions for future research and provides a bibliography of prominent works on curiosity and motivation.

Weiner, B. (2010). The development of an attribution-based theory of motivation: A history of ideas. Educational Psychologist, 45(1), 28-36. doi:10.1080/00461520903433596

Attribution theory is based on the idea that perceived causes of prior achievements determine future efforts. Weiner proposes four main perceived causes of achievement outcomes: ability, effort, task difficulty, and luck. If someone perceives a cause of failure as subject to future change, say lack of effort or bad luck, they will tend to hope for better results next time. However if the failure is attributed to an unchanging cause like personal aptitude, the person is likely to expect future failure and feel hopeless. The locus of control, that is who owns the cause, is key to how one attributes success or failure. Weiner concludes with misgivings about linking expectation of success with performance, because the role of expectations varies greatly from one situation to the next.

Young-Jones, A., Cara, K. C., & Levesque-Bristol, C. (2014). Verbal and behavioral cues: Creating an autonomy-supportive classroom. Teaching in Higher Education, 19(5), 497-509. doi:10.1080/13562517.2014.880684

This study is presented in the context of self-determination theory. The authors performed an experiment to test whether controlling vs. supportive verbal and nonverbal language delivered by audio, video, or both would influence college students’ sense of autonomy. They found that even in brief initial interactions an instructor’s autonomy-supportive language led students to experience more positive perceptions of the learning climate and stronger intentions to take the course in the future. Students will be more likely to seek out an instructor if they are perceived as autonomy-supportive even after a short interaction. They recommend the use of autonomy-supportive words like “consider,” “suggest,” “encourage,” “invite.” It’s best to avoid “must,” “should,” “required,” but if such words are necessary it is important to give students the opportunity to ask questions.

Works Cited

Brophy, J. (2004). Motivating students to learn., 2nd ed. Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. (2004-13777-000).

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Dewey, J. (1913). Interest and effort in education. https://doi.org/10.1037/14633-000

Krapp, A. (1999). Interest, motivation and learning: An educational-psychological perspective. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 14(1), 23–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03173109

Mueller, C. M., & Dweck, C. S. (1998). Praise for intelligence can undermine children’s motivation and performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(1), 33–52. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.1.33

Nakamura, J., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2002). The concept of flow. In C. R. Snyder, S. J. Lopez, C. R. Snyder (Ed), & S. J. Lopez (Ed) (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology. (pp. 89–105). New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press. (2002-02382-007).

Renninger, K. A. (2009). Interest and identity development in instruction: An inductive model. Educational Psychologist, 44(2), 105–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520902832392

RUSA. (2008, September 29). Guidelines for Behavioral Performance of Reference and Information Service Providers [Text]. Retrieved June 14, 2018, from Reference & User Services Association (RUSA) website: http://www.ala.org/rusa/resources/guidelines/guidelinesbehavioral

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 54–67. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1020

Storms, M. D., & McCaul, K. D. (1976). Attribution processes and emotional exacerbation of dysfunctional behavior. In J. H. Harvey, W. J. Ickes, & R. F. Kidd (Eds.), New Directions in Attribution Research (Vol. 1, pp. 143–164). Hillsdale, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Young-Jones, A., Cara, K. C., & Levesque-Bristol, C. (2014). Verbal and behavioral cues: creating an autonomy-supportive classroom. Teaching in Higher Education, 19(5), 497–509. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2014.880684