Revisiting Alignment in Course Design

Designing learner experiences, especially when those learners do not have the benefit of immediate and continuous synchronous feedback opportunities, requires us to revisit:

i) the purpose of the course or program of study,

ii) the activities that allow learners to identify and apply concepts, and

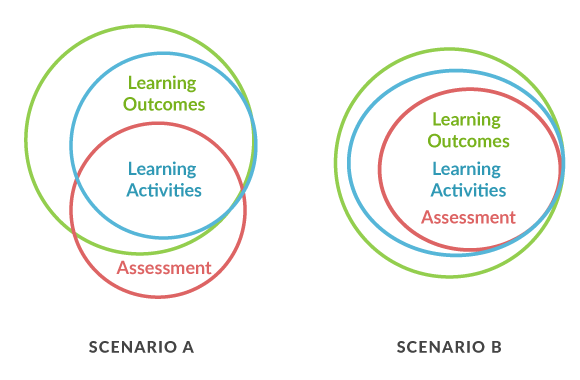

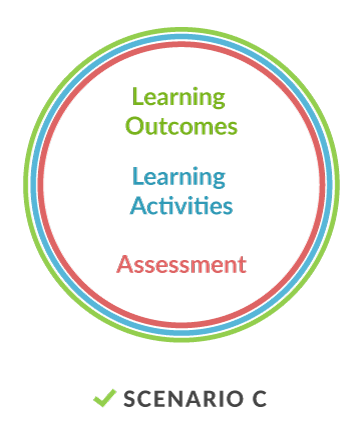

iii) options available to us to assess the degree to which outcomes have been achieved.Consider the image 4.1 at the top. If we consider the misalignment of those circles as a misalignment of the learner experience, what might the learner feel, accomplish (or not), and perform (or not) in each of the two scenarios?

The goal when designing for impact is to structure a course that is “a creative mix that investigates established knowledge while engaging in a process of establishing knowledge… a structure that is simultaneously constraining and enabling – imposing rules that delimit possibilities and that allow choice at the same time” (Davis et al., 2008, p. 194). These constraints are necessary to guide a learner from what they already know toward higher domain specific knowledge in as efficient and engaging a manner as possible.

Teaching, then, should not be about telling, but about organizing experiences that “orient learners’ perceptions to particular details and prompt them to associate those details to other details” (Davis et al., 2008, p. 168). A learning experience must be just that; experienced. We must design our course with learning, not teaching, as our central focus.

In Chapter 3, we’ve discussed how to write learning outcome statements and adopt an outcome-centred approach to decide the course structure. In this chapter, we will provide an overview of how to plan course instruction in blended/online spaces that are highly and positively impactful for student learning. We will discuss

- Planing teaching and learning activities to promote active learning

- Designing assessment tasks

- Integrating the in-class and online learning in blended learning environment

- Mapping learning activities and assessment with technical tools

Teaching and Learning Activities in Blended/Online Spaces

The outcome-centred approach to course structure (introduced in Chapter 3) indicates a thematic course structure in which each course theme/unit is composed of tasks (and even subtasks) specifying the outcomes (behaviours) students will be expected to achieve and corresponding course content that students will need to utilize to accomplish the required tasks . As such, in planning your teaching and learning activities, it is helpful to consider each instructional unit or module as a learning object. A learning object is a self-contained and complete instructional package that combines content, practices, and assessments that is sufficient to enable students to achieve at least a single learning outcome. In an online environment, a learning object would be a chunk of electronic content, which is what we usually call the individual online course module/learning unit.

Components of a Learning Object:

- Learning outcomes: What students are expected to be able to accomplish at the end of the module. When we aggregate the learning outcomes of all course modules, we will have course learning outcomes.

- Teaching and learning activities: What the students will do (and what the instructor will facilitate) to enable students’ achievement of learning outcomes.

- Assessment tasks: What activities and assignments will be used to gauge students’ successful achievement of learning outcomes.

Our discussion will focus on designing the teaching and learning activities that support students’ achievement of the learning outcomes you have created for your course, as well as the assessment tasks that will help you determine if and how students are achieving these outcomes. We will begin with a short overview of active and passive learning before discussing types of activities that offer important pedagogical considerations while scaffolding the students’ learning experience.

Making Pedagogical Decisions – Planning Activities to Promote Active Learning

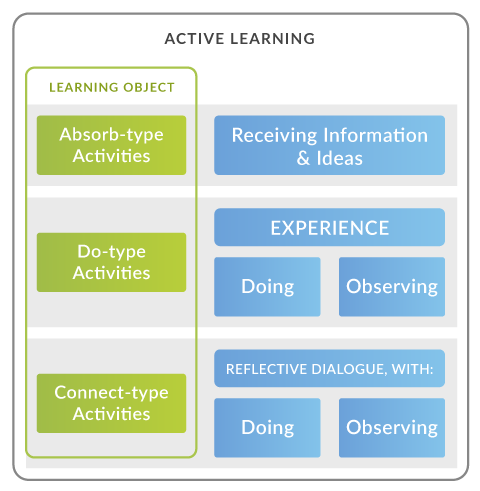

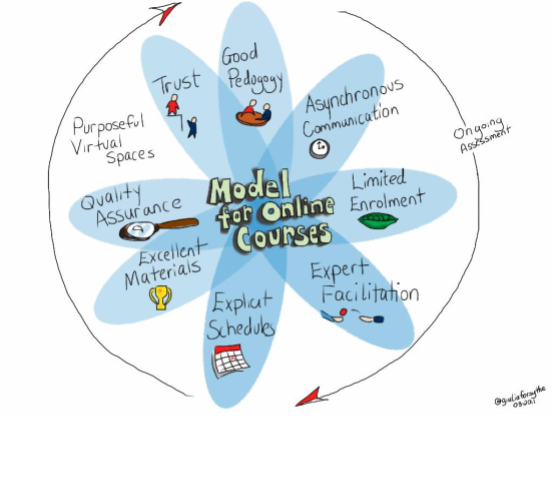

Do you still remember the formula of effective eLearning: E = M2CI (Horton, 2012)? Motivation is the determinant for the effectiveness of a learning environment and active learning is one effective strategy for encouraging or increasing student motivation. In this sense, we need to ensure that the learning object we create enables an active learning environment. But what is an active learning environment? What do we need to include/create to establish such an environment, online or offline? The graphic below outlines key elements of active learning, adopting Fink’s integrated course design model (Fink, 2003) and Horton’s activity types (Horton, 2012).

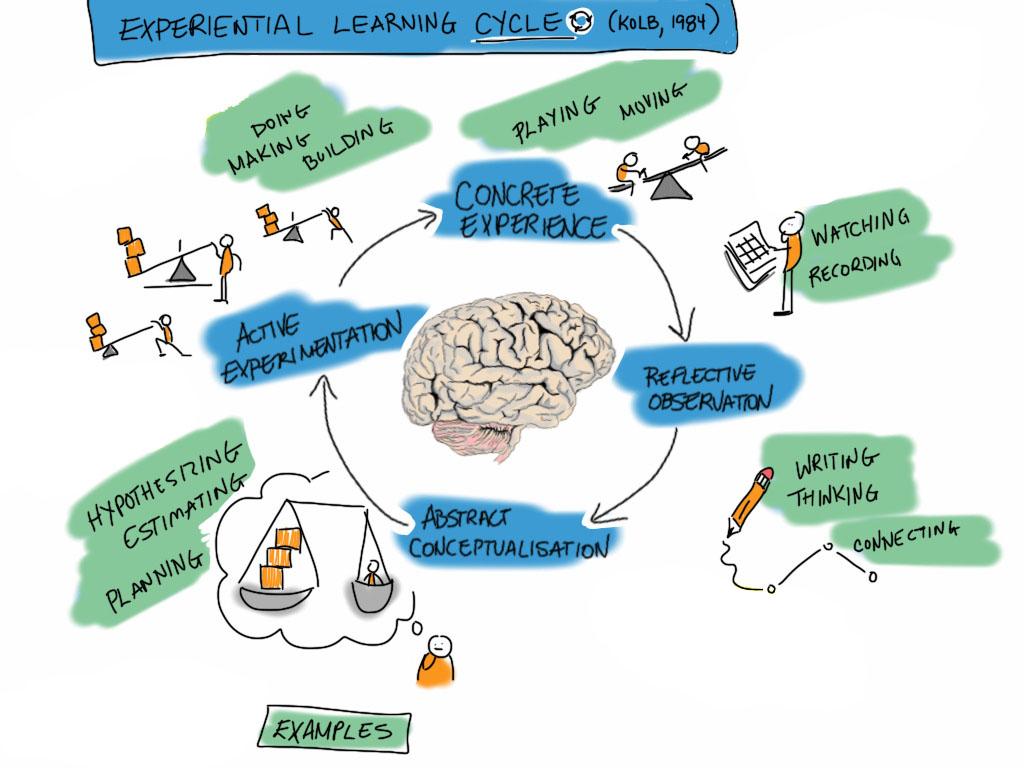

This model is rooted in social constructivist learning theory. The assumption is that meaning has to be actively constructed rather than passively received, all within and while considering the unique learning context (Vygotsky, 1980) . Nevertheless, the receiving of information and, concurrently, how information is provided or shared, is an indispensable component to active learning. Students have to be introduced to and receive the necessary information for any kind of expected learning to happen. While traditionally information is often transmitted to students in a passive way, for example via sitting in a lecture, it does not mean, however, the information being received has to be passive.

Receiving information does not, on its own, mean that the students are learning; students have to learn from and through experience. They have to be given the opportunity to use the information they are given at the expected proficiency level as stipulated by the course’s’ learning outcomes. Students should have adequate opportunities to have first-hand experience in using the information to accomplish appropriate tasks or, at the very least, observing someone else performing these tasks if having a first-hand experience is not feasible.

However, experience with the information received on its own also does not necessarily lead to learning. The social constructivist believes that learning happens when learners can make sense of new information and experiences by connecting them with their existing knowledge base and prior experience through self and peer reflections. This is where knowledge is constructed and learning truly happens. Despite colloquial sayings, students do not learn from experience; they learn from the insights they gain through reflecting on their experience. Reflection in this context does not only refer to students reflecting on what they are learning, but also includes reflection on the learning process.

As such, an effective active learning environment is one that builds on and centers around anticipated outcomes, providing information to consider, experiences to apply the information, and opportunities to reflect on and make connections between what students know, what they have learned in class, and how they may make use of it out in the world . It therefore takes three components: Information Receiving; Experience; and Reflection, to make the learning active. This means that for each learning outcome that you want to teach in your course, you will need to plan a set of teaching and learning activities that will enact the three elements of active learning. The key question to answer here is:

What will students have to do to receive the necessary information, have first-hand/second hand experience in applying this information, and have reflective dialogues with themselves, peers, and instructors to make connections and make sense of the information received and their experience so that they will achieve the learning outcomes?

Designing for Active Learning: Learning Activity Sets

Each learning object should be tied to at least one learning outcome. In ensuring students are able to achieve this outcome, we will need to make some pedagogical decisions around choosing effective teaching and learning activities that are aligned with what we want students to know, do, or feel. For each learning outcome, we need to plan a set of appropriate and engaging learning activities to enact three elements of active learning for a motivating and active student learning experience (Horton, 2012). Corresponding to the three elements of active learning, the learning activity set should be composed of:

- Absorb-type Activities: to receive information

- Do-type Activities: to experience working with, analyzing, and/or applying the information

- Connect-type Activities: to reflect on what was learned and the overall learning experiences

Having a learning activity set for each learning outcome of your learning objects ensures that your students will experience a complete learning cycle, allowing them to more deeply engage with your course content. Each activity type on its own helps students to better understand your course content. Taken together, these activities provide a robust learning experience where students learn to actively work with, not just passively take in, information and ideas. It is important to note that these three types of activities are by no means mutually exclusive. The key is to ensure that for each learning outcome, all three activity types need to be included to enact each and every element of active learning. It does not mean that you will have to have three activities for each learning outcome. Often, we will have one activity to enact more than one elements of active learning or it might take more than one active to sufficiently address one element of active learning.

In the following sections of this chapter, we will briefly outline the three overarching activity types and discuss the selection of each activity type to create an engaging learning environment for students. Selecting activities to use for each activity type should be a pedagogical rather than technical decision. You will need to consider:

- Do these activities provide students with appropriate opportunities to receive the necessary information, practice/observe the application of the information corresponding to the learning outcome, or reflect on the subject and their learning process?

- Are students actively engaged? In other words, do they have to take responsibility for their learning rather than just being passive recipients of the information?

- Where will each activity happen? Will, and when will, learning happen inside or outside the classroom? If the activity will happen outside the classroom, do we need students to perform the activity online?

- If the activity will happen online, what technological tool(s) will be needed to facilitate students’ engagement and learning?

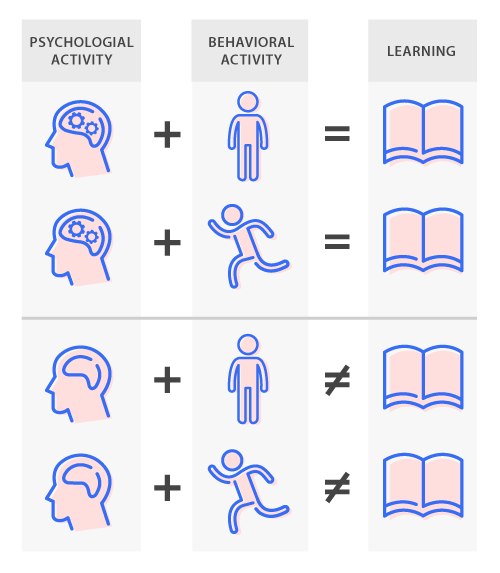

To actively engage students does not mean that you need to have them all singing, dancing, or even moving around (high behavioral engagement)in class. Teaching and learning that involves high levels of behavior activities but lack active mental engagement (such as clicking on-screen buttons to navigate and playing computer games) do not necessarily translate into learning. Learning happens when students are psychologically engaged, i.e., processing content cognitively to acquire new knowledge and skills via cognitive tasks including selecting and attending to key information, organizing materials into coherent verbal and visual presentations, and integrating new information with prior knowledge, as opposed to just passively absorbing the information transmitted by the subject experts like empty vessels (Clark & Mayer, 2011). This certainly does not mean that you will need to abandon your presentations or lectures – sometimes these are the most effective and efficient ways to expose students to the necessary content. But it is crucial to make the lecture or presentation active by integrating or following up with the Do-type and Connect-type activities such as group note taking, summarizing the main points, and asking questions so that student will actively engage with the content you provide.

How much of each element is needed in the design?

Faculty sometimes ask what proportion of time students need to spend on each element of active learning. There is no hard and fast rule to answer this question. It really depends on the learning outcomes and students’ prior knowledge of the subject. However, there is some general guidance that you can use for reference. According to William Horton (Horton, 2012), the recommended proportion for Absorb, Do, and Connect is 40-50-10: students should ideally spend 40% of their time receiving information, 50% practicing, and the other 10% on reflecting. However, sometimes you might have some simple activities which take less time in one element and therefore allow for additional time in another element depending on your learning outcomes, course content, and the learners themselves. For example, there could be some situations where students need to spend more time on receiving information, with less time devoted to practicing and reflecting. For example, when it is an introductory course with first year students who largely lack the desired knowledge base, the instructor might want to choose a 70-20-10 combination in some learning objects where there is a need for some extensive exposure to new information. In this case, you might want to have your students work in groups to absorb the information and present to each other as Absorb-type activities, then spend some time online or in the face to face class to practice using or applying the information, and then reflecting on their learning by developing some frequently asked questions or a glossary of terms. In a fourth-year advanced course where students have built a solid foundation of the content knowledge, you might want to do the opposite – spending less time on knowledge Absorption and more time on Doing and Connecting fundamental concepts using higher order cognitive tasks.

Designing Learning Objects – Elements of Design

The activities you select for learning objects should remain intimately tied to their learning outcomes. When selecting activities for each element of active learning, it is important to keep in mind that activities should complement rather than compete with student learning; students may need to remember steps to complete a task or call upon a certain skill or skillset, but the task itself should not be so complex or onerous that completing the activity becomes a learning outcome in itself. The discussion and examples below provide important details that will help you make an informed decision on which activities will be best suited for students’ capacity, your available resources, and, as always, the learning outcome(s) you are hoping your students will achieve.

Absorb-type Activities

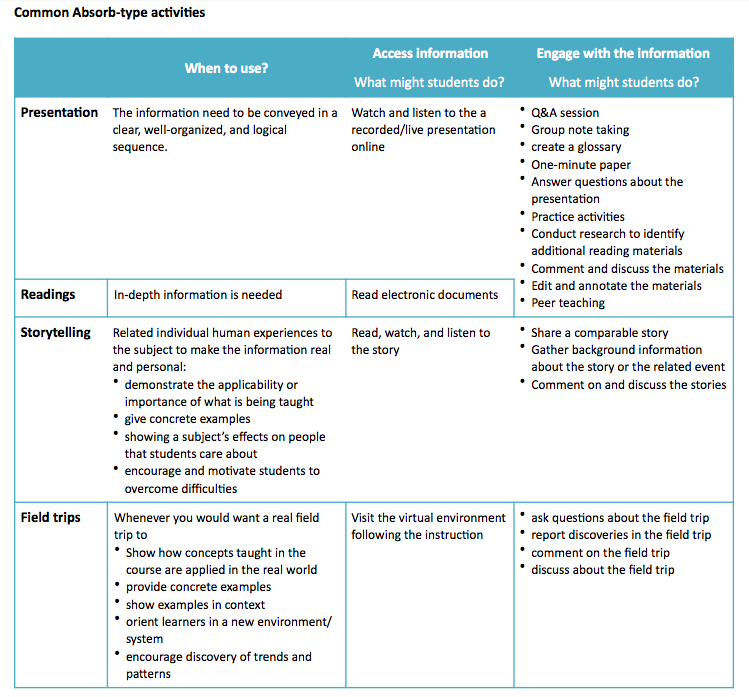

Absorb-type activities are essential scaffolding tasks for student learning. They enable students to actively engage with the necessary information they need to perform and accomplish the required tasks as specified by learning outcomes. Beyond the simple provision of ideas or content, developing and facilitating engaging Absorb-type activities will help your students begin to make meaning of the course material while providing a valuable foundation for later learning experiences and deeper (formative or summative) reflection.

To help ensure that students will actively engage with the information mentally, the Absorb-type activities generally consist of two parts – 1) providing access to content itself and 2) the tasks the learners have to accomplish to cognitively engage with the content by actively perceiving, processing, consolidating, considering, and judging the information.

You want to ensure that students are exposed to information that are relevant, up-to-date, accurate, and reliable. You also want your Absorb-type activities provide a necessary base to enable students to accomplish the Do-type activities : you are not aiming at asking students to use the information as expected by the learning outcome. The aim is to make sure students read the information, understand the content, and uncover what problems or difficulties that they might have with their initial comprehension of the topic area. This is where students will have to work to convince the instructor that they have read and understood the information by accomplishing certain tasks. These activities also allow instructors to gain insight into what students have learned and what they might find difficult in order to address any emerging issues and potentially adjust their teaching or teaching activities accordingly. For example, to encourage student’s active engagement with the course materials, some instructors may even have their students seek out information on their own to complement (or replace) more traditional course materials. It is important to note, though this exercise might lead to higher cognitive engagement, it also requires students a deep understanding of information and digital literacy. For a more in depth examination of developing digital literacy, you can review resources from Cornell University and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Common Absorb-type Activities

Click here to view the Common-Absorb type Activities table

Important Considerations: Presenting Information Using Technology

While many instructors may rely on textbooks and other similar means of sharing information, the continued rise in digital technologies has reshaped the information landscape. Webpages, uploaded documents, PowerPoint slides, audio clips, and video clips are the most commonly used tools to provide students with core course content. Some tech savvy instructors might also want to utilize newer and more sophisticated technical tools to provide access to information. Many instructors consider that multimedia has advantages in both transmitting information and motivating students to retain and engage core concepts. However, some research suggests otherwise and cautions instructors in using too many modes of content delivery or in using tools that are complex or not user-friendly for beginners. It is best to choose a tool that is familiar and easy for both you and your students to use. Try to avoid asking your students to download, install, and use unfamiliar software. Don’t use complicated technologies unless they are absolutely needed, and don’t over complicate your course by implementing many different types of technology. If a new or unfamiliar technical tool is required in your course, it is important to allow students (and yourself) ample time to learn and practice how to use it and it is imperative to expect that both you and your students might encounter a steep learning curve.

Multimedia elements, i.e., graphics, animations, video, and audio can help promote learning if they can help to clarify the course content and are designed appropriately for instructional purposes . Keep in mind that the novelty effects that may come with using multimedia won’t last long; though it might be helpful to use these tools to draw students’ attention, they can also distract from your key messages or core ideas.

There are some evidence-based principles that you will want to pay attention to when using these elements in your learning objects. Please note that graphics in the following principles refer to static illustrations, such as drawings, charts, or photos, as well as dynamic graphics such as animations or video clips.

- Present your content using both graphics and text instead of in words alone.

- Minimize the amount of graphics used solely for aesthetic or decorative purposes. It is best to avoid using graphics that may be interesting but are not essential to the knowledge and/or skills to be learned.

- Use graphics that are relevant to instructional purposes. For example:

- Use images to illustrate concrete facts, concepts, and their parts.

- Use animations to illustrate hands-on procedures

- Use graphics to show structures among ideas or lesson topics or where parts are located within a whole structure.

- Use graphics to show quantitative relationships among variables.

- Use a video to show how to operate equipment or how something might change over time, for example, a video might be more effective showing how a cell divides than having static images and a paragraph of text.

- Use a series of interpretive graphics to explain how a system works or to make invisible phenomenon visible.

- Learning could be improved when graphics presented are explained using audio narration rather than relying on on-screen text: use texts for reference, technical terms, and directions for practice exercises.

- Unless it is necessary, describe the graphics with either audio narration or on-screen texts, not by concurrent narration and redundant text.

- On-screen text can be narrated if there are no accompanying images (a word of caution: you must also comply with the AODA guidelines).

- Present words as text when language is challenging (e.g. linguistic differences, technical jargon).

- Do not add extraneous sounds in the form of background music or sounds.

- Less is more. A simple visual that omits extraneous elements leads to better understanding than a complex one.

- Present the core content with the minimal amount of words and graphics necessary to help students understand the main points.

- Use conversational language rather than formal style: writing with first- and second-person language, speaking with a friendly human voice, and using polite wording to establish a conversational tone.

- Break a lesson into bite-size segments. Materials should be presented in manageable segments such as short clips of narrated animation controlled by the learner (stop/continue/rewind/replay), rather than a continuous unit such as a long clip of narrated animation.

- Students’ attention spans often decrease even more rapidly online than in a classroom lecture. Online students also tend to study in smaller chunks of time because of their other life commitments. A single 50-minute lecture online is therefore not ideal for sharing information. Retention tends to be better when studying is spread over frequent but shorter periods of time. If you must use lecture capture, think about structuring your lecture so that it can be recorded in or broken down into separate sections that are a maximum of 10-15 minutes each.

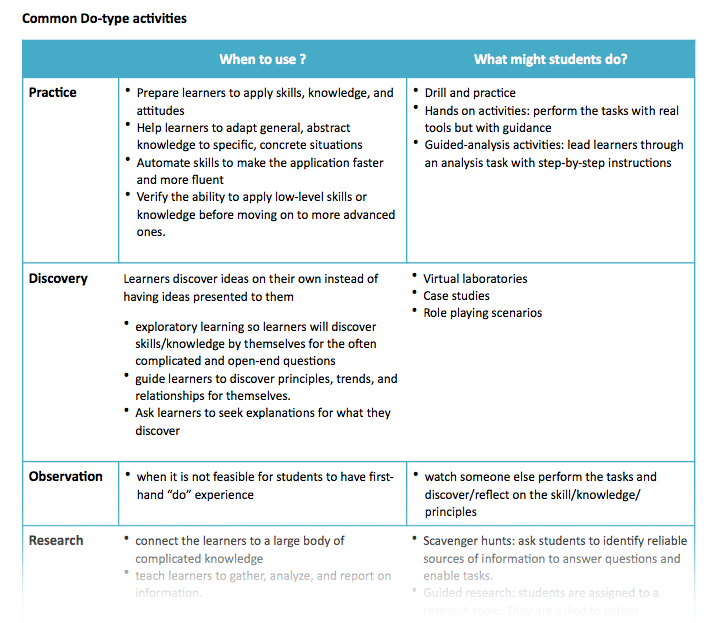

Do-type Activities

Do-type activities are tasks that you will provide students with first-hand (doing) or second-hand (observing) experience of using the information they learned in the Absorb-type activities at the expected level of the proficiency. What you want your students to do or experience will be determined by the learning outcomes and influenced by your students, the context, the nature of the subjects and your teaching styles.

Do-type activities build on students’ ability to obtain and understand information and provide opportunities for using course content to demonstrate their development of knowledge and skills, at individual and/or . Do-type activities are experiential in nature and focus on providing students sufficient opportunities to practice the anticipated behaviours to learn and receive feedback. It is essential that the Do-type activities are coherent to learning outcomes: Do-type activities will require students to do something at the same, if not higher, level of understanding as defined by learning outcomes. You will also want to consider whether students will be able to do what is expected all at once or if they will need to be supported and guided via additional scaffolding activities. For example, if the learning outcome is to have students write literature review for academic papers in a certain discipline. It’s necessary to have Do-type activities to require students practice writing literature reviews and receive feedbacks. Having students to review and critique sample literature views are good scaffolding activities but won’t be sufficient to enable expected learning if it won’t be followed by writing exercises.

Feedback should be an integral part of Do-type activities. Whenever possible, it is always recommended to focus on providing formative feedback (their strengths and weakness and how they can improve at at least one if not various points throughout the learning process) in a timely fashion so that they can learn and work to improve their performance accordingly, either later on in the same lesson or in future courses. Whenever you can, grading Do-type activities ( at least give participation marks) is also a good practice for motivation purpose. Instructions and feedback students received in Do-type activities make students know what is expected of them, help them see the relevance of the course materials, and guide them to draw the connections between the classroom learning with the real world.

Common Do-type Activities

Click here to view the Common-Do type Activities table

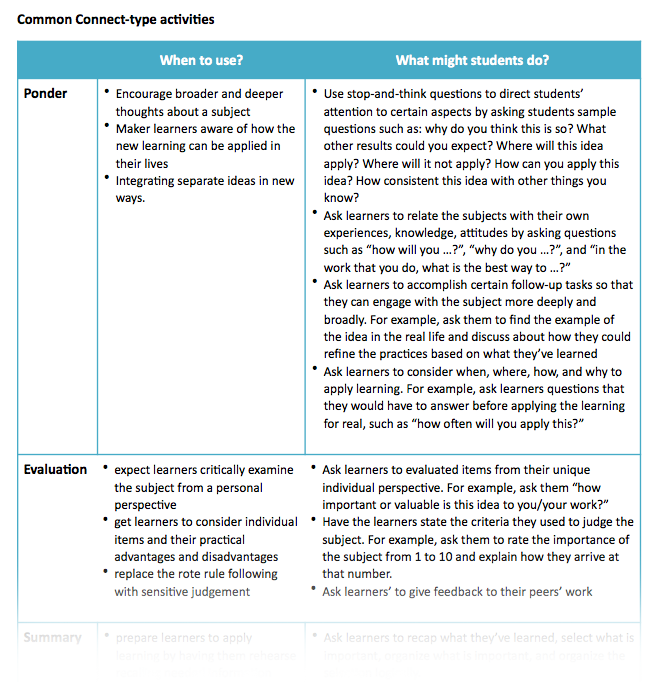

Connect-type Activities

Connect-type activities are tasks enabling students to connect information, knowledge, skills, and attitudes, and experiences with their prior knowledge, personal experience, and future learning. These activities bridge the gap and integrate what students are learning and what students already know. These activities are often where students actively make sense of their learning experience so that new Knowledge/Skills/Attitudes (KSAs) are constructed and retained. Sometimes, it might be easy to confuse the Connect-type activities with the Do-type activities. To know whether an activity is a Do-type activity or a Connect-type one, consider the primary purpose of the activity: if the purpose is to practice doing something new, then it is a Do-type activity. If the purpose is primarily to connect new learning to existing knowledge, preparing and prompting learners to apply learning in real life situations they might encounter, or critically examining the learning process, it is a Connect-type activity.

Connect-type activities often round out a course module or lesson, though they can also be used to segment or scaffold learning experiences into manageable sections. At their core, Connect-type activities are designed to assist students in making connections between course material and other facets of their lived experience; activities should emphasize opportunities to integrate course material with other information, experiences, and emotions the students bring with them into your course. Connect-type activities also offer important stopping points for students, and instructors, to look back on their learning experience as well as critical junctures for developing action plans for how newly acquired knowledge, skills, and attitudes will be used to achieve future goals.

Click here to view the Common-Connect type Activities table

Have diverse and realistic activities

One important factor to keep in mind when designing and reviewing your course activity schedule is that your students may have different strengths for working through and completing different learning activities. Some students, for example, are strong in processing and consolidating a large amount of information, while others may prefer active, synchronous engagement with peers or the instructor to review information rather than individual, quiet study time. Designing your course to include opportunities for students to engage in various types of interactions with materials, peers and the instructor not only ensures a richer experience, but helps students develop a more well-rounded approach to their own learning. The goal is not to make students good at everything or to excel in all activities, but rather to provide students, and yourself, opportunities to approach material in different ways and to stretch beyond what is familiar to inspire new ways of thinking, feeling, and doing. Exploring whether students have, in fact, acquired new knowledge, skills, or attitudes will be the focus of the next section.

Alongside the pedagogical considerations, the instruction you’ve planned needs to be realistic and manageable to be effective and impactful for student learning. You will also need to consider the following practical issues. These considerations might call for or inspire some revisions to your initial design.

- Are the technological tools that you want to use in your course easily available to you and your students? Are they supported by the university? If not, how easy would it be for you and your students to get the technology support that you might need? Do you have a plan B if the technology fails?

- Are you and your students comfortable with and have the skills to use the tools? We cannot assume that students know how to use these tools for their learning even though it might be usual for most of them to use these tools for other purposes. A detailed set of expectations and information about the use of these and all technology tools should always be available for students.

- Are you and your students comfortable with the teaching approaches that the design and technology implies? For example, if you choose to have students review materials online so that you can use the class time to engage them in hands-on activities and discussions, how comfortable are you initiating these learning strategies? If this will be a major change to you and/or your students, you need to start small and give both your students and yourself time to prepare and get used to it. Remember, students often need some level of training to be able to learn actively.

- How much of an addition is this work to your current workload? There could be a significant investment of time to design and develop courses with eLearning components. Depending on your current skills and previous experience, this preparation could take a minimum of 20 -30 hours if tools are not new and you taught the course previously in the face to face classroom. Though with practice, instructors should be able to spend the same amount time to prepare for an eLearning course as you need for your face to face ones, additional time might be needed for new instructors and new courses. Take a look at your design and consider whether you have enough time to design and develop the course and how far in advance you need to get started.

- How will this course and its activities add to your students’ workload? A 3-credit hour course normally equals roughly 100 hours of study for students. Keep in mind that students might have to take 2-3 times the amount of time that a faculty member would take to accomplish the same task, and longer still if these tasks are to be completed online. Take a look at your design; would it imply a reasonable student workload?

Assessment in Online/Blended Spaces

Assessment is an integral components of any instruction. Designing an effective course is to structure an experience that attempts to enact and make student learning “visible”. Instructional design must therefore work toward having students “create, talk, write, explain, analyze, judge, report, and inquire” as these activities support learning and development that moves from being aware of concepts to acquiring and applying concepts (Boettcher, 2007, p. 5). Alongside these activities, assessment should be embedded within instructional events. Learning outcomes must not be merely aspirational; assessment strategies should be an integral part of any course design. Often, assessment tasks and learning activities overlap. Many learning activities can serve dual purposes: both to confirm that the targeted knowledge, skills, and attitudes (KSAs) are incorporated into practice and incorporating assessed practice will support the accomplishment of KSAs as well as producing evidence of learner accomplishments (Boettcher, 2007, p. 6). There are also two circumstances that you might consider adding extra formative and/or summative assessment:

- When students’ prior knowledge to certain learning outcomes are essential to their learning. For example, lab safety might be a crucial prior knowledge to your course. Before you have your students conduct any experiences in your lab, you probably want to include a diagnostic assessment of lab safety at the beginning of your course. Student who fail the lab safety assessment will be required to study additional materials.

- After learning outcomes are considered as particularly relevant or important (key assessment points). For example, in a research foundation course, you might identify each data analysis method is a key assessment point where you want to include a quiz to let students know how well they are doing in the course and have formative feedback.

Principles of Effective Online Assessment

Morgan & O’Reilly (1999) outline six key qualities for assessing students engaged in online learning. These qualities offer a valuable method of framing our assessment strategies across various tools, platforms, and classroom contexts.

| Quality of Effective Assessment | What Does This Look Like? |

| Clear rationale & consistent pedagogical approach |

|

| Explicit values, aims, criteria, and standards |

|

| Authentic & holistic tasks |

|

| A facilitative degree of structure |

|

| Sufficient & timely formative assessment |

|

| Awareness of the learning context and perceptions |

|

Common assessment strategies

Much like the learning activities discussed earlier in this chapter, many different strategies can be used to facilitate opportunities for student assessment. The table below provides sample assessment strategies to consider when designing assessment activities for your course. Many of these strategies can also be used and/or adapted to design learning activities.

| Assessment Strategy | Potential Advantages & Risks |

| Tests & Quizzes | Potential Advantages:

Learners, and instructors, can receive near instantaneous feedback on their learning Online polling platforms allow you to quickly and efficiently collect large amounts of data on student performance Polling platforms often work particularly well for large classes; Polling can offer opportunities for both assessment and engagement with ready, quick access to student responses Potential Risks: Not all polling or testing technologies are easily accessible to students; Not all students may have a smartphone or the funds to pay for additional tech tools (e.g. clickers) Not all platforms allow for multiple types of questions; Some tools, for example, may only work well for multiple choice quizzes or tests |

| Rubrics | Potential Advantages:

Emphasizes and celebrates growth and development rather than solely focusing on a students’ ‘all or nothing’ achievement Pre-determined criteria can help provide meaningful feedback – where is the student now and where do you want them to improve? Online rubrics can be easily edited and used multiple times across different classes and learning activities Potential Risks: It is often helpful for students to be able to view your rubric as a way to plan their work; Consider how easy it is to download and/or share your electronic rubric across different platforms It can take a lot of work to identify criteria that students will need to demonstrate in each section of the rubric; Consider how you will break down a complex task (e.g. writing) into its component parts and levels |

| Formative assessments

(e.g. reflective journals, pre-assessment tasks, think-pair-share activities) |

Potential Advantages:

Data from multiple formative assessments can be stored and tracked using technology, allowing instructors to view and analyze student progress over time Learners can practice what they’ve learned and receive (more) timely feedback on their work Potential Risks: Formative assessments may require students to quickly learn a new technology or tool; Consider what tools your students may already be familiar with and what tools may take more time in explaining rather than in their useage Synchronous communication (assessment) demands immediate answers that may be intimidating, while asynchronous communications (assessments) may be demotivating or inauthentic over too long a period of time |

| Summative assessments; Outcome-oriented activities to make a decision or judgement of a student’s’ overall learning and/or development

(e.g. research essay, multiple choice exam, portfolios) |

Potential Advantages:

Using technology for summative assessments can offer students the opportunity to demonstrate their learning across multiple modes of expression Technology for summative assessments can allow students to provide additional artifacts or evidence to accompany an assignment (e.g. multimedia artefacts alongside a text-based essay) Potential Risks: It may be difficult to find a ‘standard’ to grade across different modalities or tools, particularly if students are submitting final assignments using different means of expression (e.g. audio, written, etc) Having access to the Internet and other online resources requires students become (or move toward becoming) digitally literate; Consider how you will assist students in finding relevant and accurate information online to complete their assignments |

Important considerations for assessing eLearning

- We can only assess what we can see. Consider how your assessment tasks will allow students to demonstrate their learning and development. For example, if your learning outcomes include developing skills in public speaking, consider whether the assessment tasks you use will allow students to evidence their competencies in public speaking as defined in the course.

- Giving and receiving feedback are not always intuitive skills. For both students and instructors, developing competencies in providing and receiving feedback includes

- Learning to accurately, and honestly, judge abilities. This includes recognizing our strengths while also cultivating a degree of authenticity in acknowledging what may be more challenging.

- Recognizing reactions to feedback and criticism. Is our natural response to try to explain away negative feedback? Are we too quick to dispel positive praise? Do our students react the same way? Developing a strong self awareness is a valuable complement to the more academic exercise of assessment; how might our emotions enhance or resist valuable opportunities for learning?

- Looking ahead to integrating current insights with future goals. Feedback is only as valuable as the future actions it inspires. Engaging in a holistic cycle of learning and reflection must include opportunities for considering how new skills, knowledge, and attitudes can be incorporated into upcoming courses and other, novel situations.

For additional discussion on supporting and encouraging feedback, an article from Times Higher Education, “Can student feedback become a two-way street?”, offers a bidirectional approach to feedback that is an important perspective in considering assessment both with and for students.

- We measure what we value, but we also value what we measure. Could your reliance on multiple choice assessments, for example, be demonstrating that you might be only interested in how students memorize and recall information? While perhaps an important foundational skill, learner-centered assessment must also focus on holistic student development and the complexities of the learning process. What you choose to assess sends a message to students of what knowledge, skills, and attitudes will be important to them both throughout the course and beyond the classroom.

Blended learning: What to do and where?

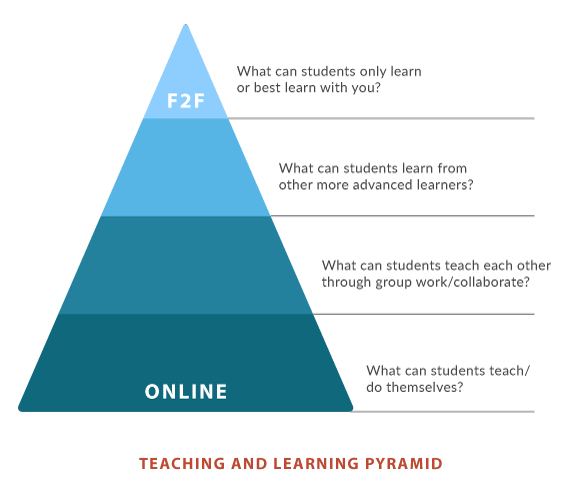

Designing blended learning instruction is to design engaging and impactful learning experiences that occur both within and outside the classroom. One important consideration is which learning experience is better to be offered online and which experience is better to be delivered in-class. The goal is to decide the most effective and efficient usage of both face to face and online spaces based on pedagogical considerations and operational constraints.

A general guideline can be presented in the teaching and learning pyramid below: activities located at the upper end of the pyramid tend to be more suited to be delivered in class while those are at the lower end of the pyramid might be successfully facilitated online.

The most popular choice is to move low/less cognitive demanding activities (such as reading PowerPoint slides) to online space and use the valuable face to face meetings to engage students with high cognitive demand activities such as debate. For example, in courses (or course units) focusing on fostering higher order thinking skills, instructors use the online environment mainly to expose students to new course materials (what students can do/teach themselves) so that they can devote face-to-face meetings to apply the new course materials in discussions and collaborative activities (what students can best learn with the instructor and their peers). However this arrangement might not be the best choice for each and every course. For example, in some foundational courses (or course units) aiming at building a solid knowledge base, instructors may prefer to reserve face-to-face meetings to ensure that students have sufficient exposure to new materials via lecture and demonstration while using the online environment mainly for practice and drill and question and answer activities to enhance the knowledge retention.

Providing blended instruction also demands a seamless integration of online and in-class activities. They need to relate to and complement each other to make the instruction a coherent whole, rather than separated instructional chunks. The online and face-to-face content should also both be considered as indispensable components of the instruction that are integral to students learning, rather than optional, substituting, and/or additional resources.

Mapping activities with technical Tools

In an online/blended learning environment, technology is a medium or vehicle to deliver the instruction. Specific technical tools are selected and used in online/blended learning environment because they can fulfill certain needs of students learning rather than using technology just for the technology’s sake. “Although technology can provide more efficient instruction, it does not necessarily provide more effective instruction” (Morrison, Ross, Kalman, & Kemp, 2013, p. 224). With the advancement of the technology, there is an ever-increasing set of technical tools available that can offer a multitude of ways to collect, analyze, display, and store data in pursuit of better learning. The tools you include in your course should reflect the different and diverse modes through which students take in, work with, and analyze information. Ideally, we choose the modes of delivery of our instruction based on pedagogical considerations rather than the assumed novel or interesting experience the technology might bring. The focus is not what technology that you want to use, rather, it is what you will ask your students to accomplish with technology acting as a tool to enable these activities to occur. You might, therefore, use the same technical tools for very different purposes.

On the other hand, different technological tools have different characteristics and some tools might be more appropriate for certain kinds of learning and activities than others. We can still argue whether one tool is better than the other for any particular circumstances/tasks. The success of utilizing any tools rests on

- Choosing the right tool for the purposes

- Using the tools appropriately

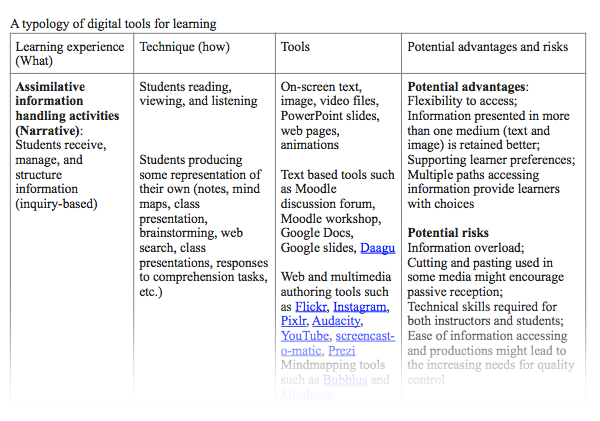

Dianna Laurillard’s conversational theory of learning (Laurillard, 2002) has been particularly influential when thinking about the choice and use of digital technologies for learning. Conversational theory distinguishes five different media types (narrative, communicative, interactive, productive & experiential) with different capacities to mediate learning. Appendix A summarizes conversational theory’s classification system, tools that can support different learning activities/tasks, and suggests advantages and risks in each category. Please note that the techniques and tools listed are by no means exhaustive and a particular digital tool can be used to deliver a variety of learning experiences.

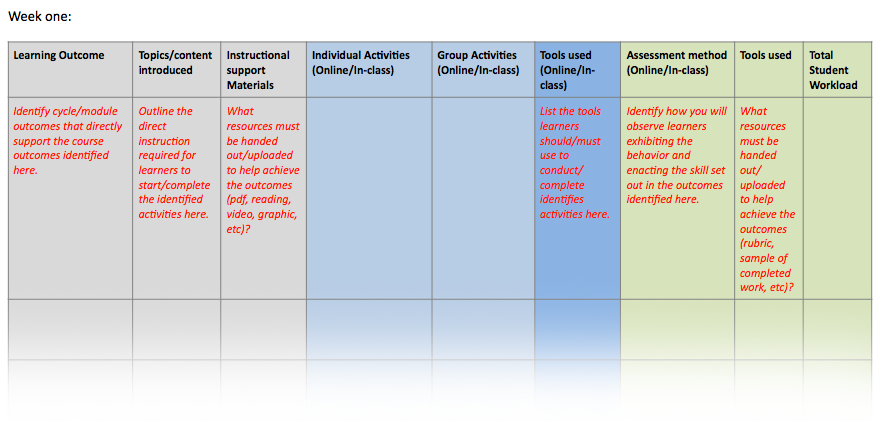

A Concept Mapping/Course Blueprint – An Activity for Designing for Impact

With so many ideas, tools, and strategies to consider in designing for impact, it can feel overwhelming just to get started. As you consider your own lesson planning, a concept map, what we call a Course Blueprint, may be a helpful tool to begin identifying and organizing the many components required for effective teaching and learning. For the purpose of this book, we are sharing the a Course Design Document we have been using (continuously improving) at York University to help instructors to document their concept for course design (see Appendix B).

You can also create your own Course Blueprint concept map by reflecting on the questions below (this article on concept mapping is a useful resource):

- Who are your students? What experiences and expertise do they bring to the classroom?

- What core concepts are most important for your students to know about the topic(s) being taught? Can you identify materials/other resources that will help explain these ideas?

- What learning outcomes have you set for your students? How will you know if and when they are achieved?

- What technological tools or platforms will help you achieve your learning goals?

- What teaching strategies and assessment tools are viable or possible given the time and resources you have available?

- How will you encourage and respond to feedback? What formative assessment strategies will help you gather information to inform students’ learning and your teaching?

Chapter Summary

“Educational technology is not a homogeneous ‘intervention’ but a broad variety of modalities, tools, and strategies for learning. Its effectiveness, therefore, depends on how well it helps teachers and students achieve the desired instructional goals” (Ross, Morrison, & Lowther, 2010, p. 19).

When creating and facilitating online learning, the ten online teaching practices listed below will help ensure an effective and efficient experience for both you and your students:

- Be present on the course site. While some level of autonomy is helpful and perhaps necessary, students are looking to you for guidance and support. Be sure to actively demonstrate your diverse roles as observer, assessor, and partner in your students’ learning.

- Create a supportive online community. Just as you will lead and support your class throughout the learning experience, consider how your students might be able to support their peers.

- Develop a set of explicit expectations for your learners and yourself as to how, when, and how often you will communicate with each other and how much time students should be working on the course each week.

- Use a variety of large group, small group, and individual teaching & learning strategies to vary the learning experience and to offer all students the opportunity to demonstrate strengths and develop in areas for growth.

- Use synchronous and asynchronous activities to explore different modes of active learning, reflection, and information receiving.

- Ask for informal feedback early, and often, in the term; formative assessments are mutually beneficial for students to gain feedback on their learning and for instructors to receive feedback on their teaching & learning activities.

- Prepare discussion posts that invite responses, questions, discussions, and reflections rather than only relying on close-ended questions that may test students’ memory or motivation but not their learning; never underestimate the power of a well-worded, open ended question.

- Search out and use content resources that are available in digital format if possible; model principles in digital literacy by searching for and sharing information that is presented as relevant, timely, and accurate.

- Combine core concept learning with customized and personalized learning; Students may all need to learn the same material, but they often learn best in many different ways.

- Plan an appropriate closing and wrap activity for the course. What might you want your students to tell their peers about what they learned? How do you want your students to incorporate their learning into future courses or other activities?

Designing a learning experience with technology is often not much different than designing for the physical classroom; our approaches must still be learner-centered in considering not just what we hope students will achieve but also how we will help students reach these goals. A course that includes activities for flexible information receiving (Absorb-type activities), meaningful experiences (Do-type activities), and critical reflection (Connect-type activities) helps to create many and varied conditions for success in which learners have multiple, diverse opportunities to engage with course material rather than only passively taking in ideas. In an age where employers are looking for graduates who speak clearly, think critically, and work effectively with others, designing your course with these principles in mind will be especially impactful for students entering the working world. A careful consideration of the alignment between your teaching tools, topics, and learning outcomes will help to ensure your online or blended classroom supports deep learning, critical reflection, and a truly authentic classroom experience.

Reflective Questions and Tasks

“Skills need to be embedded within a subject or knowledge domain. Thus there are implications for setting learning goals (what is to be learned), curricula (what is to be taught), teaching methodology (how it is taught or learned), and assessment (what is to be examined or assessed). Each of these areas must be adequately addressed, if learning goals … are to be achieved.” (Bates & Sangra, p. 20)

- Can you think of an example from your own teaching and/or learning experience where an instructor (or yourself) used an example of an Absorb-type, Do-type, or Connect-type ?

- What made this activity effective? (Consider how it helped to achieve a particular learning outcome).

- How might you incorporate these ideas into your own teaching?

- Think of one learning strategy or activity you are currently using (or have used) in a face to face course. What might this activity look like online? Is there a particular tool or platform that may help you facilitate this activity using technology?

- How are you currently collecting formative assessment data in your course?

- If you are currently only using summative assessment tasks, what is one formative assessment tool you could incorporate? When in the term or semester could you use it as a way to collect valuable feedback?

- If you are currently using formative assessment tasks, what are you doing with the feedback you receive? Do your students know that you have considered their feedback and are (potentially) making changes in response to their ideas or questions?

Appendix A

Click to view the Typology of Digital Tools for Learning table

Appendix B

Click here to view the Course Design Plan

References

Anderson, T., & Elloumi, F. (2004). Theory and practice of online education. Canada: Athabasca University.

Bates, A. W. (n.d.). Teaching in a digital age: Guidelines for designing teaching and learning. Retrieved from https://opentextbc.ca/teachinginadigitalage/

Beetham, H., & Sharpe, R. (Eds.). (2007). Rethinking pedagogy for a digital age: Designing and delivering e-learning. New York, NY: Routledge.

Boettcher, J. V. (2007). Ten core principles for designing effective learning environments: Insights from brain research and pedagogical theory. Innovate: Journal of Online Education, 3(3), 2.

Davis, B., Sumara, D. J., & Luce-Kapler, R. (2008). Engaging minds: Changing teaching in complex times (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge.

Fink, L. D. (2003). Creating significant learning experiences: An integrated approach to design college courses. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Horton, W. (2012). E-Learning by design. (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Wiley and Sons.

Larman, C., & Vodde, B. (2009). Scaling lean & agile development: Thinking and organizational tools for large-scale scrum. Boston, MA: Pearson.

Laurillard, D. (2002). Rethinking university teaching. A conversational framework for the effective use of learning technologies. London: Routledge.

Clark, R. C., & Mayer, R. E. ( 2011). E-Learning and the science of instruction: Provide guidelines for consumers and designers of multimedia Learning (3rd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Wiley and Sons.

Meier, D. (2000). The accelerated learning handbook: A creative guide to designing and delivering faster, more effective training programs. McGraw Hill Professional.

Morgan, C., & O’Reilly, M. (1999). Assessing open and distance learners. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

Morrison, J. R., Ross, S. M., Kalman, H., & Kemp, J. E. (2013). Designing effective instruction (7th ed.). Wiley & Sons.

Palloff, R. M., & Pratt, K. (2011). The excellent online instructor: Strategies for professional development. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Palloff, R. M. & Pratt, K. (2009). Assessing the online learner: Resources and strategies for faculty. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Ries, E. (2011). The lean startup: How today’s entrepreneurs use continuous innovation to create radically successful businesses. New York, NY: Crown Books.

Ross, S. M., Morrison, G. R., & Lowther, D. L. (2010). Educational Technology Research Past and Present: Balancing: Rigor and Relevance to Impact School Learning. Contemporary Educational Technology, 1(1), 17-35.

Vygotsky, L.S. (1980). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.