7 555-10 – Earthquake in Haiti in 2010

AI-generated overview from Google Gemini:

On January 12, 2010, a devastating earthquake of magnitude 7.0 struck Haiti, leaving an indelible mark on the nation.[1] The epicenter, located just 15 miles southwest of the capital, Port-au-Prince, unleashed a catastrophic force that leveled buildings, shattered infrastructure, and claimed the lives of hundreds of thousands.[2] The quake’s impact was exacerbated by Haiti’s already fragile state, marked by poverty, political instability, and a history of natural disasters.[3]

The immediate aftermath was a scene of utter devastation. The quake reduced much of Port-au-Prince to rubble, burying countless people beneath the debris. Hospitals, schools, government buildings, and private residences were all indiscriminately destroyed. The Haitian government, already struggling with limited resources, was overwhelmed by the scale of the disaster. The death toll, initially estimated in the tens of thousands, eventually climbed into the hundreds of thousands, with over a million people displaced from their homes.

The international community responded swiftly, sending aid workers, medical supplies, and emergency relief funds to Haiti. The United Nations, the United States, and other nations established a coordinated effort to provide humanitarian assistance. However, the logistical challenges of delivering aid to a country with a damaged infrastructure and a history of political instability were immense.

The initial phase of the response focused on search and rescue operations, providing immediate medical care, and distributing food and water to survivors. As the days turned into weeks, the focus shifted to providing shelter, sanitation, and rebuilding essential infrastructure. International organizations and NGOs played a crucial role in these efforts, establishing temporary shelters, setting up medical clinics, and providing clean water.

The American Red Cross had an AIDS program in-country in Haiti, so when the earthquake struck, they were able to help the Haitian Red Cross society immediately. Every country which has a Red Cross or Red Crescent society (and the Magda Adom in Israel), has its own sovereignty, just as the country does. And some Red Cross and Red Crescent national societies do things very differently than others. In Mexico, they do search and rescue – same for Switzerland. In India and the Middle East, they operate ambulances. But they are all humanitarian-focused and follow the Fundamental Principles mentioned in the introduction.

American Red Cross 10 Year Anniversary Report

January 02, 2020

When a devastating earthquake struck Haiti on January 12, 2010, neighborhoods were destroyed, rubble lined the streets, families were separated and hundreds of thousands of lives were lost.

Within moments, Haitian Red Cross teams responded to the devastation even as their own families suffered losses. That day, the American Red Cross joined the global effort to aid the wounded and displaced.

Americans opened their hearts and gave generously to save lives and help people recover—and that’s exactly what their donations have achieved over the past ten years.

THANKS TO DONATIONS:

- 4.4 million people benefitted from hygiene promotion activities

- 601,000 people covered by disaster preparedness and risk reduction activities

- 402,000 people benefitted from livelihoods assistance

- 3.6 million people benefited from cholera prevention and outbreak response services

- 969,000 people benefited from community health services

- 164,800 people reached through housing and neighborhood recovery

- 631,000 people benefited from access to improved water and sanitation

In the earthquake’s aftermath, the American Red Cross provided food, water, medical care, emergency shelter, cash grants and other essentials to millions of people—spending $148.5 million in the first six months alone. And when a severe cholera outbreak occurred, the Red Cross distributed relief and provided 70 percent of the funds needed for the country’s first cholera vaccination campaign. The US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) subsequently called the effort, “one of the best coordinated and documented responses to a cholera outbreak in modern public health.”

Looking back, it’s easy to forget the significance of immediate aid such as this, but people whose lives were touched by the aid will always remember.

Since then, Americans’ donations have funded the operations, construction or equipping of more than 50 hospitals and clinics. The generosity of the American public helped to renovate or reconstruct 48 schools and assisted more than 164,800 people through housing and neighborhood recovery.

Other parts of the American Red Cross work are less visible—but just as critical. Donations enabled us to grant seed money to local Haitian entrepreneurs; train disaster responders for future emergencies; address gender-based violence; pay for university education for talented students; strengthen the Haitian Red Cross and so much more. Work has focused on providing essential services to the most vulnerable—especially children, the elderly, people with disabilities and those not served through other programs.

Disaster relief and recovery is a true team effort. The American Red Cross ensured that the majority of our staff was Haitian; funded more than 50 organizations large and small; and made certain that all projects were driven by community members themselves—all in service of the Haitian government’s national earthquake reconstruction plan and in partnership with the Haitian Red Cross.

No single organization can address every need in Haiti, but our American Red Cross donors can be proud that their generosity helped Haitians on their long road to earthquake recovery.

Donations Strengthen Haiti’s Health Capacity

“I want my children to be healthy. This gives me peace of mind,” says Leonel, one of many parents whose kids received free measles, rubella and polio vaccinations in Haiti. Leonel and his wife, Loramise, are eager to keep their twins—who survived a complicated birth—healthy. So when Red Cross volunteers came to their door and explained the health risks associated with vaccine-preventable diseases, they knew immunizing them was the right thing to do.

American Red Cross’s participation in Haiti’s vaccination campaigns is part of a larger investment in the country’s health infrastructure. Thanks to generous donations in the earthquake’s aftermath, the American Red Cross has supported more than 50 medical facilities in Haiti. Funding has ranged from a few thousand dollars for medical equipment to millions for large-scale construction work on new facilities. This includes $5.5 million towards Mirebalais University Hospital, a state-of-the-art teaching hospital run by Partners In Health.

“Every time I got pregnant, I would lose the child,” remembers Caroline, a patient at Mirebalais who received urgent surgery to remove a tumor. “The doctor has given me a chance of having children.”

From reconstructing the Haitian Red Cross blood bank and fighting epidemics to funding the construction of the country’s first wastewater treatment plant, Americans’ donations for the Haiti earthquake made positive changes in people’s access to essentials like clean water and healthcare.

‘Home’ is More than Four Walls and a Roof

The earthquake dealt an immense blow to Haiti’s infrastructure, and an estimated one quarter of the capital city’s population was displaced. The global Red Cross network moved fast: providing emergency shelter to more than 860,000 people in the quake’s aftermath. Meeting this immediate need was a lifesaving act, but it’s not the end of the story.

Over the past ten years, the American Red Cross has provided more than 164,800 people with safe housing and neighborhood recovery support.

As earthquake recovery efforts moved forward, it was clear that building brand new homes for every family wasn’t a scalable solution or a responsible use of resources. Given the physical landscape, land tenure issues, and people’s desire to stay in their neighborhoods, the American Red Cross focused instead on offering realistic and durable shelter solutions to Haitians. Most Haitians were renters before the earthquake, so we funded rental subsidies to help Haitians leave camps and move into rentals. We repaired, strengthened, and expanded houses to create more secure rental stock; erected transitional and progressive shelters that could be easily expanded to create permanent structures once land tenure issues were resolved; and trained construction workers on safe building techniques.

Families in Haiti lost more than physical homes in the earthquake—they lost neighborhood assets including schools, clinics, roads, and critical infrastructure. Haitians told us that remaining in their neighborhoods to rebuild and improve their quality of life was the priority, so in addition to investments in housing, the American Red Cross repaired and reconstructed schools, built large water systems, and planted thousands of trees. By constructing bridges, roads, sidewalks, and public spaces like parks and sports fields, we helped neighbors connect to one another and restore a sense of cohesion.

Investing in Entrepreneurs

“My lifelong dream is being achieved,” says Ferdinand, an earthquake survivor and entrepreneur. Ferdinand received seed money from the American Red Cross to buy essential equipment for his business: a coffee roaster, mill, refrigerator, grill, kitchen supplies and a laptop computer. Soon after receiving the $10,000 USD, he was able to train and hire fifteen people to work at his company, turning local produce into jams, creams and liqueurs.

Ferdinand is one of more than 400,000 Haitians who benefited from livelihoods assistance from the American Red Cross over the past ten years. Establishing new careers helped earthquake survivors regain a sense of dignity and financial independence.

The Red Cross utilized donations from the American public to address the economic impacts of the disaster. This includes cash grants to entrepreneurs like Ferdinand; technical training for welders, bakers, computer scientists and other professionals; scholarships for students’ university education; and savings and loan groups to help people achieve financial goals. Interventions like these are not always visible to the public, but they empower people to take charge of their careers.

How did the Red Cross spend Haiti earthquake donations?

Thanks to generous donations to the American Red Cross, more than 4.5 million Haitians have been helped since the earthquake.

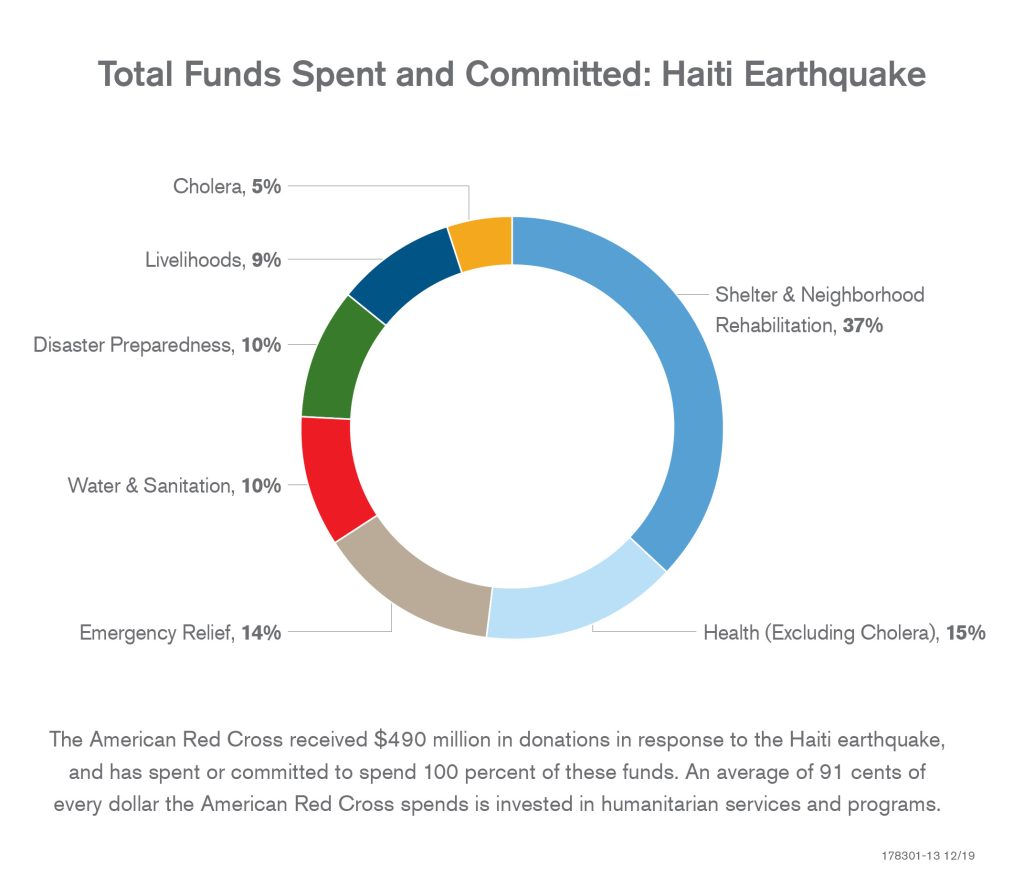

The American Red Cross published this complete financial breakdown of the $490 million received for Haiti earthquake relief and recovery. This chart details all the projects undertaken by the American Red Cross’s Haiti Assistance Program, including grants to partner organizations. We believe this breakdown sets a new standard of transparency for the non-profit sector.

Dollars donated for Haiti earthquake relief and recovery were allocated to seven sectors (see Figure 1):

- Emergency Relief: $66 million

- Shelter and Neighborhood Rehabilitation: $182 million

- Health: $77 million

- Cholera Prevention: $24 million

- Water & Sanitation: $47 million

- Livelihoods: $44 million

- Disaster Preparedness: $50 million

Thank You

Disasters are heartbreaking, but they also bring out the best in people. Americans’ generosity during the earthquake was matched only by the resilience of those affected. Donations literally saved lives in the quake’s aftermath, provided immediate assistance for millions, and supported hundreds of thousands of people to move forward in a long recovery process with dignity and hope.

Somewhere in that $66 million in Emergency Relief was the programs the American Red Cross supported within the United States for Haitian refugees/immigrants.

U.S. Federal Declaration for Temporary Protected Status (TPS)

Given the size of the destruction and humanitarian challenges, there clearly exist extraordinary and temporary conditions preventing Haitian nationals from returning to Haiti in safety. Moreover, allowing eligible Haitian nationals to remain temporarily in the United States, as an important complement to the U.S. government’s wider disaster relief and humanitarian aide response underway on the ground in Haiti, would not be contrary to the public interest.

DHS estimates that there are 100,000 to 200,000 nationals of Haiti (or otherwise eligible aliens having no nationality who last habitually resided in Haiti) who are eligible for TPS under this designation.

Designation of Haiti for TPS

Based upon these unique, specific, and extreme factors, the Secretary has determined, after consultation with the appropriate Government agencies, that there exist extraordinary and temporary conditions in Haiti preventing aliens who are nationals of Haiti from returning to Haiti in safety. The Secretary further finds that it is not contrary to the national interest of the United States to permit Haitian nationals (or aliens having no nationality who last habitually resided in Haiti) who meet the eligibility requirements of TPS to remain in the United States temporarily. See INA section 244(b)(1)(C); 8 U.S.C. 1254a(b)(1)(C). On the basis of these findings and determinations, the Secretary concludes that Haiti should be designated for TPS for an 18-month period. See INA section 244(b)(2)(B); 8 U.S.C. 1254a(b)(2)(B).

source: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2010/01/21/2010-1169/designation-of-haiti-for-temporary-protected-status

Of those folks who came from Haiti to the United States immediately following the earthquake – I estimate more than 10,000 families – came right to New Jersey. And they needed help with food, clothing, healthcare, education for their children, pretty much everything. Many came with one suitcase or less. Everything else was destroyed or missing.

In the education sector alone, the Ministry of Education (MENFP) stated that 82% of the schools (public and private), located in the affected regions, were damaged or destroyed* (i.e., 4,000 schools damaged and 2,000 destroyed out of 7,300 schools located in the affected regions).

* Financed by the Haiti Grant Facility of the Inter American Development Bank

Source: https://blogs.iadb.org/educacion/en/aid/

We had two Red Cross operations in the state – at the time we were organized into separate chapters – probably about 15 or so spread across the state – and worked pretty much day-to-day independent of each other. There was (and still is) a large Haitian population in the City of Elizabeth, New Jersey – which was in the geographic jurisdiction I covered when I was an emergency services director at the Red Cross. Also at that time, emergency services directors covered International Services and Service to the Armed Forces – so this earthquake response in the U.S. fell right into my lap, and mine alone.

I remember when the earthquake occurred on that January day, how quickly everything we did at the Red Cross became focused on that effort – both in Haiti and here in the U.S. I imagine 9/11 was a bit like this for the Red Cross groups outside of New York City and the area around the Pentagon as well.

Seriously, the telephone would not stop ringing – and it was mostly people who heard about the earthquake on the news and wanted to go and help. As in go to Haiti. We were not sending any U.S. volunteers to another country – that’s not what the American Red Cross normally does (there are times when American Red Cross staff will support an International Red Cross incident in another country, as part of a request by the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent societies, and there are times when the American Red Cross has asked for help from neighboring Red Cross societies inside of the United States, from our partner societies in Mexico and Canada. I will mention that again in the chapter on Superstorm Sandy.

That was every day for the first week. Then people from Haiti started to arrive at our doorstep.

And the State of New Jersey recognized it had a challenge on its hands as well. This was a large influx of people coming in who had no jobs, no income streams, no access to healthcare, no vaccinations, no identification papers other than their passports (some of which were missing or questionable) and no educational planning for their children. The state set up a center for intake -with the various state departments needed for all the items above – at a county college in Elizabeth. Unfortunately, that school wanted each of the non-governmental organizations to cover the liability insurance for the entire facility – and our Red Cross legal/risk management team would not do that. Which made sense to me right away – why should we be on the hook for an accident in another part of the building or grounds, where there was not a Red Cross operation? That’s not how we do it for shelters or other Red Cross-managed facilities, and that was not how we were going to do it for this disaster.

We coordinated with a church in Elizabeth which was Haitian-focused, as well as a non-profit group who had offices in Elizabeth and was also supporting the Haitian community there. At both sites we set up client casework, first with me and a few volunteers and a paid staff worker floating in and out, and eventually with a part-time hire dedicated to this casework, along with volunteer case workers coming from a national deployment.

We were providing a debit card with (I think) $150 per person for food, clothing and incidentals. It was not a lot of money in my opinion – about the same as what we were providing for clients who had home fires back then – as there was no precedent for this. And at the time, no other NGO providing across-the-board financial support for Haitians in the United States. Still, we filled out all the forms, cross-checked a spreadsheet we shared with another chapter in New Jersey (since there were some bad actors who would try to visit both sites in NJ to double-dip if they could) and did this for weeks.

At one point we were processing cases for more than 50 families a day. Those dollar amounts caught the attention of the Red Cross’ National Headquarters, and they sent a ‘fixer’ to see what we were doing, and eventually plan out as to how to unwind and cease this operation.

Lessons Learned

I learned very quickly to ask for help. Plead for it. I also learned how to advocate for a difference between program costs and overhead costs, when it comes to how a non-profit runs. I also learned some hard lessons about spontaneous unsolicited in-kind donations. And I learned the importance of having a strong incident command system being in place (it was not) and a repeatable battle rhythm of incident action planning (that was not done then, either). Our organizational construct of being siloed chapters and only really getting together (officially and routinely) for meetings and exercises within the state, was not sustainable. And when something big came around back then – and NHQ came ‘parachuting in’ to run the operation, two things happened – we did not gain leadership experience, and our constituents did not benefit in the longer-term from any mitigation capabilities. In other words, in my opinion the Red Cross had not yet learned the lesson of building back better. That set of lessons I would help the Red Cross learn and apply to New Jersey in 2012, with Superstorm Sandy.

Lessons Applied

- I already knew that if donations were marked as ‘restricted’ they had to be spent only on that disaster. That was anecdotally shared with me later in more detail, regarding 9/11 (see that chapter for those specifics). For now, the lesson which was applied was to have our chapter finance folks strongly request (as in ‘if you don’t fund us for this, we cannot do it and the organization will look very bad) that NHQ carve out some of the “Emergency Relief” funding, to support well, emergency relief. Only it was in the United States for Haitians, not in Haiti for Haitians. A drop in the bucket for what was going on over there – but a major shift and a game-changer for how we supported Haitian families here in the United States. Once we could utilize even a miniscule amount of the nearly half-a-billion dollars donated for Haiti earthquake relief, we were able to support the part-time staff, bring in volunteer caseworkers from around the country (while their time was free, their hoteling, travel, and food costs were not), and still provide that $150 or so per client.

- Normally, today the Red Cross is about 90% efficient (https://www.redcross.org/donations/where-your-money-goes.html). And back in 2010, the figure was about 93%. That translates into how much of your donation goes into programs. Lots of people think that means it goes out the door to clients, but that is only part of it. The costs of the paid staff – who are not in management or fund-raising – who support those programs, the costs of buildings/upkeep, vehicles/fuel, and other expenses to run these programs is also in that 90-93%. The remaining amounts cover the management and fund-raising expenses, known as M&G or management and general expenses. So those pesky letters you get every month from charities – and those sad (or sometimes uplifting) TV commercials you see from some non-profits all come from the M&G portion of the dollars donated. So, when we started the Haiti work – and were getting in donations restricted to Haiti, we were told to only spend 7% as a chapter – including at the start of the casework that $150 we were providing for clients. That had to change – and thankfully, it did very quickly.

- I also learned from this disaster that everyone in the Red Cross is responsible for fundraising. Whether they know it or not. Also, everyone must be an expert on what local classes that Health and Safety is offering, where folks can get CPR training, and of course when and where the next blood drive is. When I would drive a Red Cross vehicle to a fast-food drive-thru window, the workers would ask me those questions (I kept an updated clipboard with the info); and during the Haiti earthquake, I had people flag me down to hand me cash. Another lesson learned and applied: keep a cash receipt book in the Red Cross vehicle, just in case.

During those weeks of earthquake response, after work I would go to businesses who were doing fund-raisers to pick up checks – those were the best – because cash is king and is the most flexible in its use by us. We, of course, honored the donor intent and deposited it as a restricted donation – there are accounting strings for both the income and expenses associated with each DRO code. Setting up those strings is one of the first things that happens by NHQ when a DRO is assigned (as noted, typically when the costs are $10k or more).

On the flip side, there were those spontaneous unsolicited in-kind donations. Not the same scale as 9/11 (see that chapter for specifics), but still a challenge, nonetheless. Two examples came to mind – one a lesson learned not applied, and the other one I do think worked out in the long-run.

First, we had someone anonymously send a private-carrier (I can’t remember if it was UPS or FedEx – but still it must have cost someone some bucks) delivered box with winter coats for Haiti. Yes, it was January here. But they never need winter coats in Haiti. Plus, how was I supposed to get them there? Those went right into our own local clothing bins. No fuss, no muss. A few weeks later, that church in Elizabeth which was helping, was also overwhelmed with used clothing, odds and ends – like lamps, and culturally insensitive food donations.

Next, we got a call from a firehouse in a town I will not mention, saying they had collected bottled water to send to Haiti and wanted us to pick it up. I asked who told them we could deliver bottled water to another country? They thought we did this all the time. I told them to call the local food pantry to donate it there – and that unless they had the complete logistics supply chain in place not to collect for any other incidents, please, please, please. In other words, the Red Cross would not handle the last-mile or even the first-mile of the logistics for these. I would say they were probably well-meaning, but like those callers, had no real idea how bad things were in Haiti – and they certainly did not know that all the ports were destroyed. Plus, shipping was going to be take about six months and add a cost of $6 per bottle of water – and there was no guarantee that anyone other than gangs or pirates would get the water, once it possibly arrived in Haiti. And that it would arrive:

During the rainy season, when there is quite a bit of water available. And at that point, Haitians needed tarps more than bottles of water.

Finally, there was an elementary school in my jurisdiction who wanted to collect bottles of water – just like the firehouse. Luckily, they called me before they started collecting. I offered them an alternative – I would come there and meet the kids (and their parents!) and tell them about Haiti and the curse of the unsolicited in-kind donations. They got the story about the $7 water bottle (this time including the cost to buy the bottle itself) and how it would be much more effective to collect the $7 and send it to the Red Cross or any other NGO helping down there, instead. They still wanted to collect stuff (oh, well), so I recommended those small toothpaste tubes and toothbrushes you get from the dentist, and the shampoo and conditioner bottles you get from hotels. Their parents were excited about this. Both help the Red Cross locally as components to comfort kits, given out at home fires and other everyday disasters in New Jersey.

[1] https://www.dec.org.uk/article/2010-haiti-earthquake-facts-and-figures

[2] https://www.worldbank.org/en/results/2019/05/03/rebuilding-haitian-infrastructure-and-institutions#:~:text=Recorded%20as%20Haiti’s%20most%20devastating,estimated%20230%2C000%20people%2C%20injured%20300%2C000

[3] https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/haiti/overview