9 144-13 – Superstorm Sandy in NJ

Sandy in New Jersey: DR-4086-NJ

In many ways, I can probably write an entire book about my Superstorm Sandy adventures in New Jersey, which were outside of the Red Cross (maybe I will someday). For this book however, I will focus on the Red Cross-related leadership lessons learned and applied later on – that is what will probably work best. At least for now.

AI-generated overview from Google Gemini:

Superstorm Sandy’s impact on New Jersey in 2012 was devastating, leaving a lasting mark on the state. Here’s a breakdown of the key effects:

- Unprecedented Storm Surge:

- The storm’s most destructive element was its massive storm surge, which inundated coastal communities.

- Record-high water levels were recorded, particularly in areas like the Raritan Bay and along the Jersey Shore.

- The surge caused widespread flooding, destroying homes and businesses.

- Widespread Damage:

- Hundreds of thousands of homes were damaged or destroyed.

- The Jersey Shore, a vital part of the state’s economy, suffered extensive damage to boardwalks, amusement parks, and other infrastructure.

- Beach erosion was severe, and new inlets were created in some areas.

- Power Outages:

- Millions of New Jersey residents lost power, some for extended periods.

- This disruption affected daily life, essential services, and the economy.

- Economic Impact:

- Superstorm Sandy was the costliest natural hazard in New Jersey’s history, with billions of dollars in economic losses.

- Loss of Life:

- Tragically, the storm resulted in numerous fatalities in New Jersey.

- Long-Term Effects:

- The storm highlighted the vulnerability of coastal areas to rising sea levels and extreme weather events.

- It spurred significant efforts to rebuild and strengthen coastal defenses.

- It caused changes in building codes, and in how coastal communities plan for future storms.

In essence, Superstorm Sandy inflicted widespread destruction across New Jersey, particularly along the coast, and its impact continues to shape the state’s efforts to enhance resilience to future storms.

Superstorm Sandy prompted several significant changes within the federal government, primarily focused on disaster preparedness, response, and recovery, as well as an increased emphasis on climate resilience. Here are some key areas of change:

- Sandy Recovery Improvement Act (SRIA) of 2013:

- This legislation aimed to streamline FEMA’s processes, allowing for greater flexibility in administering assistance programs.

- It focused on expediting the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP), promoting proactive measures to reduce future disaster losses.

- Increased Focus on Climate Resilience:

- The Obama administration’s Climate Action Plan, influenced by Sandy’s devastation, emphasized community resilience.

- This included the formation of task forces dedicated to “climate preparedness.”

- FEMA Improvements:

- FEMA undertook efforts to improve communication and coordination between federal, state, and local agencies.

- There was a heightened focus on long-term resiliency and sustainability in disaster recovery efforts.

- FEMA also improved its ability to provide faster disaster assistance.

- Funding and Appropriations:

- The federal government allocated significant funding for recovery and rebuilding efforts, including the Disaster Relief Appropriations Act of 2013.

- These funds supported various agencies in repairing infrastructure, providing housing assistance, and bolstering coastal defenses.

- Department of the Interior Changes:

- The department of the interior was given funding to repair and rebuild its assets, and also to invest in future costal resiliance.

- Emphasis on Mitigation:

- There was a greater focus placed on hazard mitigation, with funds being allocated to projects that would reduce the impact of future storms.

In essence, Superstorm Sandy served as a catalyst for the federal government to enhance its disaster response capabilities, prioritize climate resilience, and invest in measures to mitigate the impact of future extreme weather events.

U.S. States with adverse impacts from Superstorm Sandy

Superstorm Sandy led to a wide range of presidential disaster declarations across numerous states. Here’s a breakdown based on the information which Google Gemini found:

- States with Major Disaster Declarations:

- New Jersey

- New York

- Connecticut

- Rhode Island.

- States with Emergency Declarations:

- District of Columbia

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Delaware

- West Virginia

- Virginia

- Pennsylvania

- New Hampshire.

It’s important to understand that “disaster declarations” and “emergency declarations” serve different purposes, and the extent of damage varied significantly across these states. However, Superstorm Sandy’s impact was widespread along the East Coast.

10 Years Later: A Look Back at Superstorm Sandy

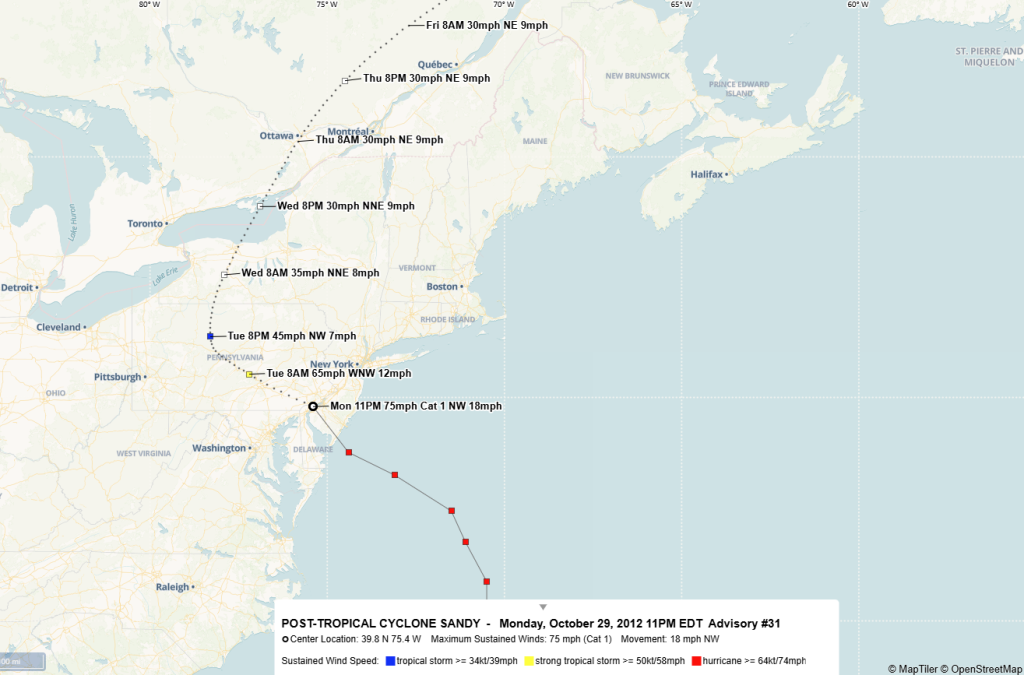

Ten years ago, the center of 900-mile-wide Superstorm Sandy came ashore near Atlantic City, New Jersey. The massive storm battered communities across several states, especially hard-hit New Jersey and New York, causing massive destruction in its wake.

Sandy’s winds, rains and storm surge — as well as snowstorms inland — re-shaped coastlines and caused devastating losses. In the U.S., 117 people lost their lives, including 53 in New York and 34 in New Jersey, while hundreds of thousands of people were forced from their homes. Storm damage left 8.5 million people without power across 11 states and sparked a massive fire in Queens, New York, that leveled more than 100 homes.

The American Red Cross was part of the massive response, working with government and community-based partners to give a helping hand to those affected by the storm. People needed help getting back on their feet and the Red Cross provided financial assistance, help with housing-related expenses, assistance planning next steps and grants to support services in areas hardest hit by Sandy.

RED CROSS RESPONSE

Emergency Relief

In response, more than 17,000 Red Cross volunteers and employees mobilized to bring relief, opening shelters and feeding sites that ultimately provided more than 74,000 overnight stays for people forced from their homes and served over 17.5 million meals and snacks. More than 300 emergency response vehicles navigated blocked roads, closed bridges and tunnels, and gas shortages as they worked to bring relief throughout the region, providing food, blankets, health care, emotional support and over 7 million sorely needed relief supplies like cleanup and comfort kits.

Recovery Support

The Red Cross Move-In Assistance Program provided case management and referrals for many impacted by the storm. In addition, this program assisted families with rent, rebuilding, repairs, temporary housing, storage and moving costs, appliances and furniture. For thousands of households with uninsured expenses, the program served as a vital bridge to relocate people from hotels to sustainable housing or complete repairs on their Sandy-damaged homes.

A recovery effort of this scale is larger than any one organization. The Red Cross also awarded grants to dozens of nonprofits with specialized expertise and strong local ties. These grants supported a network of skilled, community-based services that could best meet Sandy survivors’ needs for food, housing, financial assistance, mental health support and guidance.

The Red Cross funded food banks in New York and New Jersey communities, helping feed families facing ongoing hardship due to Sandy’s impact. We provided grants to nonprofit partners like Rebuilding Together and Habitat for Humanity to support home repair and rebuilding efforts. The Red Cross also committed $10 million to a New Jersey program that helped low-to-moderate income families with rebuilding costs that weren’t covered by federal reconstruction grants.

Additionally, the Red Cross provided more than $14 million to long-term recovery groups in New Jersey, New York and Connecticut to support some of the most complex individual and family recovery needs.

Spending

The Red Cross spent $314 million in support of our Sandy response efforts. Details on how donations were spent, including a full listing of grants, are available at redcross.org/sandy.

Looking Ahead

Ten years after Superstorm Sandy, large disasters like hurricanes, floods, wildfires and extreme heat are regularly impacting communities across the country, resulting in more people displaced, vulnerable and in need of support.

As communities across the country continue to experience more extreme weather events, the Red Cross is providing critical support on a near-constant basis to help families struggling to cope.

Millions of U.S. households are at risk of being forced from their homes with many facing the threat of poverty due to the dramatic increase in billion-dollar disasters, which have nearly doubled in the last five years compared to the previous five years.

We invite you to help prepare yourself and your community for any emergency by taking three simple steps: 1) Get a kit. 2) Make a plan. 3) Be informed. Individuals can download the free Red Cross Emergency app or text GETEMERGENCY to 90999 to get lifesaving preparedness information and weather alerts in the palm of their hand. Visit www.redcross.org/prepare for more tips and information.

Thank You

We are grateful for contributions from donors who responded with compassion to the devastation caused by Sandy; our partner nonprofits that worked alongside us in the best interests of those in need; and our team of dedicated volunteers and staff who translated plans and resources into action.

Thank you. You have made, and continue to make, a difference in countless lives.

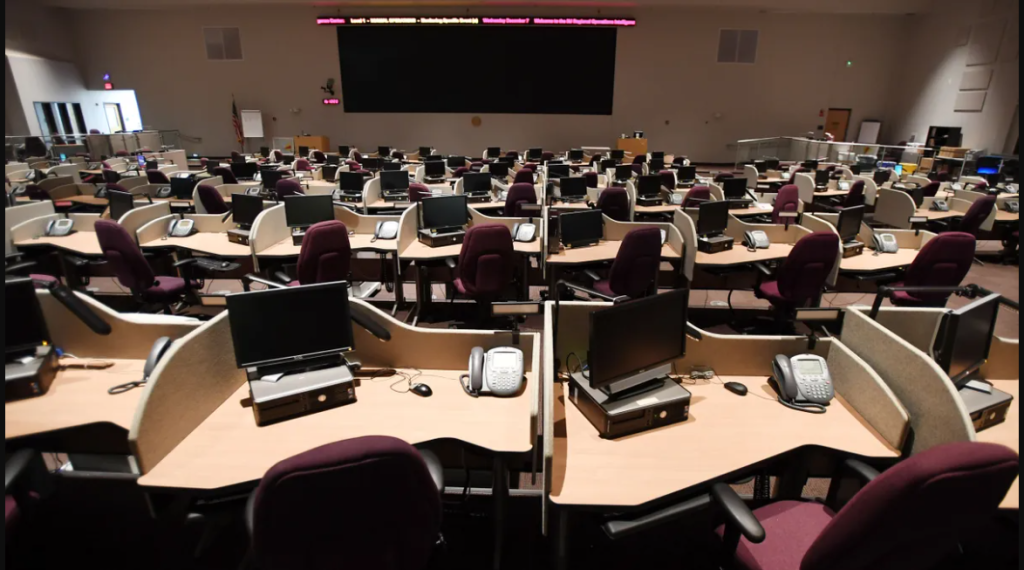

I pretty much hit the ground running during the Response phase for Sandy. I was still an employee with the Red Cross in 2012, and having experienced Irene the year before, I had learned a couple of pre-storm lessons. Mostly for personal safety and sanity. Number one of which was to prepare and protect my own family. So, unlike the first night – and next day or more – of Irene when I was effectively stuck at the State Emergency Operations Center (SEOC), I rode out this storm at home with my family. This time, we were much better prepared with power, food, and other supplies for this hurricane, as well. I had two generators (a 5,000 watt primary and a 3,500 watt, as a backup) and ten gallons of gasoline – that would last us for 24 hours straight.

FYI – We were out of power at my home for nine days straight during this storm. It was not the first time I miscalculated the level of preparedness needed for major disasters, and it would not be the last, either.

Sandy was a storm which was 1,000 miles wide and took 24 hours to completely pass by my house (and everyone else’s in New Jersey). Even if you lived away from the short, that is a lot of wind and rain for a very long time.

The next day I drove in my Red Cross sport utility vehicle from my home in Union County to the New Jersey SEOC in West Trenton. On a normal day because of traffic, this would take about 45 minutes to do. That first day, I made it there in 20 minutes, flat. No traffic other than police vehicles and fire trucks, for miles and miles.

I would go back and forth each day there, for the next thirty days. Then we moved the entire operation to a Joint Field Office (JFO) for about six months, into 2013.

During the time at the SEOC, my focus was on two major things for the Red Cross – providing intelligence to the state on the status of sheltering (in New Jersey, the Red Cross is a supporting partner for sheltering, but at FEMA we are a co-lead. This can lead to challenges with which shelters get counted, when, and by whom), and also coordinating any request to the Red Cross from government. The way the SEOC works (best) in a home rule state such as New Jersey, is when the municipalities need assistance for any emergency support functions (sheltering is part of one called Mass Care), they make a request to their county. If that county can help, they do. If the county needs help, they make a request to the state. If the state can help, it does. If it cannot, then – and only then on these large scale incidents – the state asks the Red Cross for help on sheltering. Sometimes it is other things like feeding, or distribution of blankets. Generally, it is help with mass care.

On smaller disasters, these requests may come to the Red Cross right from the municipalities or the counties; especially if the state and the SEOC are not activated. One challenge is that the counties and municipalities get used to the idea of contacting the Red Cross directly (as they do for regional/smaller flooding incidents, multi-family fires, etc.); and as we found out in Irene, they sometimes get pretty angry when that level of FREE support is not provided. This was one applecart which needed to be upset. One of the lessons learned by me from Irene was to really try and change the paradigm of this – and we needed to do it town by town, county by county across the entire state. Unfortunately with just a little over a year between these two hurricanes, we did not have enough time to complete this.

I managed 2-3 service associates and one supervisor at the SEOC – at one point for the first few days, it was two 12 hours shifts for 24 hour coverage – and also government operations volunteers and paid staff from around the country who were located at key county OEM offices. Some of them – and myself included – had dual reporting roles: within their governmental seats, and also to the Red Cross DRO which was set up elsewhere. This can be a challenge, especially if you need help. Not a lesson learned from me, because candidly I did not need the direct supervision from the Red Cross operation as a liaison officer – I was more like an extension to the command of the operation. In other words, when the state asks the Red Cross for help, that’s pretty much the marching orders for the Red Cross’ DRO.

The 30 days at the SEOC was the real response time for this incident. After that, the time spent – and missions worked on – at the JFO would be considered recovery work. There, as I noted the Red Cross’ role with the state – as far as the state OEM was concerned, was over – since sheltering was done. What they did not fully comprehend was our ongoing roles in disaster assessment for families, coordination of case management for families, our role in children in disaster planning, how in the world to get people back into their housing or create new housing units out of thin air. There was quite a bit of recovery/mitigation work needed. The state also did not comprehend the significant role the Red Cross in New Jersey – through its leadership role in the NJVOAD, and how this would help the state in its recovery. And most importantly, the role the Red Cross had in supporting the NJVOAD at the time. Part of this was due to the disjunctive nature of who does what at the state. While the overall emergency management is lead by the NJ State Police and their state office of emergency management, sheltering and feeding is lead by the NJ Department of Human Services, volunteer management is lead by the Department of State, disaster health – things like mold concerns, raw sewage in basements, etc. is lead by the Department of Health, and donations management is coordinated by the State’s Treasury Department. So sometimes I would be representing the Red Cross response work, the Red Cross recovery work, and sometimes the NJVOAD work. Lots of moving parts – and some of the folks from these state department groups had never worked in a Joint Field Office before.

Including me.

STATE PERSPECTIVE: NEW JERSEY CHILD TASK FORCE

Allison Blake, commissioner of the New Jersey Department of Children and Families (DCF), discussed preparedness and response before, during, and after Hurricane Sandy. In the state of New Jersey, DCF is responsible for Child Protective Services, all of children’s behavioral health care, and services for children with intellectual and developmental disabilities. DCF operates a network of special education schools for pregnant and parenting teens and children with profound physical impairments, and a very large network of community-based family-strengthening child abuse prevention programs. Blake noted that DCF has no responsibility or authority for sheltering or decision making around mass care. Each of the 21 counties in New Jersey has a county department of human services that is responsible for emergency sheltering and for local homeless sheltering and boarding homes; a county department of health; and an office of emergency management. In each county, there is also a board of social services (formerly called the county welfare agency) that provides temporary assistance for needy families, emergency assistance, and housing assistance. In some counties, the head of Social Services reports to the Department of Human Services, while in others it operates independently. This inconsistency across counties became one of the most complicated parts of the disaster response to Hurricane Sandy, Blake noted.

After the Storm

Devastating flooding and widespread power outages meant that many people did not have television or Internet access to obtain news. The DCF central operations, where the hotline is based, did not flood or lose power, and it became the central point of communications and operations. DCF was able to put in calls to every foster parent in the state within the first 5 days after the storm. There were also daily conference calls with FEMA and the Red Cross.

The day after the storm, the governor’s office began holding conference calls twice daily and providing reports on the number of people in shelters. Although they had data on the number of adults, senior citizens, and even pets, there were no data on children in shelters. As a result, DCF sent “well-being teams” to the shelters to meet with the Red Cross and the county staff and check on the children and families. Blake explained that the name of the teams was intentionally chosen because many people hear “State Department of Children and Families” but think “Child Protective Services.” Blake noted that although many individuals and families who stayed in longer-term shelters were not known to the public systems, they had been living on the edge and were in need of public services. DCF had public health nurses and social workers talking with these people to understand why they were still in the shelter after they were able to return to their communities or other housing options.

A key aspect of the response to Hurricane Sandy was coalition building though the activation of existing resources and relationships. Immediately after the storm, DCF contacted the human services directors in the impacted counties. DCF also reached out to the FEMA-operated disaster recovery centers to provide information about available local social services and community support. The State-Led Child Task Force was also created, focused on identifying a short-term recovery plan for children and families, and long-term recovery needs around trauma, resilience, and other issues. In addition to DCF and the New Jersey Departments of Health, Human Services, and Education, task force members included FEMA, ACF, AAP, New Jersey Volunteer Organizations Active in Disaster (VOAD), Montclair State University, Save the Children, and others. Blake stressed the importance of recognizing the unique needs of the local jurisdictions. DCF worked with the county long-term recovery committees to understand the greatest need and gaps in their communities. In January 2013, DCF issued a report on the state’s long-term recovery plan, which is focused on keeping families strong, preventing the potential negative impacts of the disaster on children and families, and providing swift support and intervention (see Box 10-2). Next steps for the state include gathering additional stakeholder feedback, tracking and adjusting in coordination with coalitions, and preparing for the upcoming hurricane season with the new working group and coalition in place.

Source: NIH – https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK195872/

During the interim recovery phase, when we moved operations for the state and federal coordination to the JFO, I knew the Red Cross had additional roles and responsibilities. At the federal level, at the time, we were a named partner to two of the Recovery Support Functions (RSFs): Housing and Health & Social Services. There are six RSFs, and for the first time in FEMA history, Superstorm Sandy activated all six. This was also the first DR where they had a Federal Disaster Recovery Coordinating Officer, in addition to the Federal Coordinating Officer (FCO). New Jersey got help from the national Red Cross operations to support these two RSFs (thank you BB and ADP!) since many times it was difficult to be in three places at once (case management meeting, state housing meeting, children and disasters meeting, voluntary agency liaison meeting, federal RSF, VAL, RSFLG or other meeting, and more). Meanwhile, the Red Cross was somewhat overwhelmed with financial and in-kind donations, that it was novel for them as to what to do. One of their financial paid staff CC was in charge of managing the design of a long-term recovery staffing group to cover all of the impacted counties, provide grant funding to other NGOs to help support the impacted families more directly (and sometimes, such as with construction/repair – not the mission of the Red Cross, directly). The Red Cross also helped convene all of the partners towards resilient housing solutions, with the help of the U.S. Housing and Urban Development (HUD) department. I became familiar with the National Disaster Recovery Framework (NDRF) and the RSFs just the year before, in 2011 – and it was at the same time – and physical meeting with FEMA in NYC! – that the NJ State Police OEM leads learned about the NDRF, too. In fact, the Major who led the NJ State Police for the SEOC, DM, who was at that 2011 meeting, retired the next year and became the disaster lead for the Red Cross in New Jersey: right before Sandy hit.

New Jersey State-Led Disaster Housing Task Force (NJ SLDHTF)

In the aftermath of Superstorm Sandy, which devastated New Jersey in October 2012, addressing the massive housing crisis became a critical priority. Several entities, including a New Jersey State-Led Disaster Housing Task Force (NJ SLDHTF) and the federal Hurricane Sandy Rebuilding Task Force, played key roles. Here’s a breakdown:

- Purpose:

- This task force was formed to develop a comprehensive disaster housing strategy, focusing on both temporary and permanent housing solutions for displaced residents.

- Its goal was to coordinate efforts between federal, state, non-profit, and private sector organizations.

- A key output was the “Disaster Housing Strategic Plan,” which provided recommendations to federal and state authorities.

- Key Focus Areas:

- Identifying and facilitating various temporary housing options.

- Expanding existing federal and state housing assistance programs.

- Providing “wrap-around” services to support displaced residents.

- Addressing the vast and dynamic housing needs, requiring flexible solutions.

- Challenges:

- The sheer scale of the housing damage.

- The need to adapt to evolving housing requirements.

Federal Hurricane Sandy Rebuilding Task Force:

- Purpose:

- Created by President Obama, this task force aimed to ensure coordinated federal support for affected communities.

- It focused on long-term rebuilding, emphasizing resilience and future storm preparedness.

- Key Focus Areas:

- Developing a regional rebuilding strategy.

- Promoting coordinated recovery efforts across federal, state, and local levels.

- Implementing measures to enhance infrastructure resilience, including flood risk reduction standards.

- Helping communities utilize CDBG-DR funds.

- Addressing the needs of renters, low income residents, and those with special needs.

In essence, both task forces worked to address the immediate and long-term housing needs of New Jersey residents affected by Superstorm Sandy. The state task force focused on the immediate housing needs, and the federal task force focused on the long term rebuilding of the affected areas.

Source: Google Gemini https://g.co/gemini/share/d21be2e86706

Lessons Learned

I certainly learned quite a few lessons in Sandy. Here are some highlights, related to leadership:

- Large scale disasters can be somewhat isolating, especially if you are in an intermediary leadership role such as being a government liaison for a non-governmental organization. Once the response phase was over (effectively the first thirty days after storm landfall, for Sandy), the Red Cross at the time would normally pack up shop and get ready for the next one. They would revert the recovery efforts – on these very large incidents of scale – to the local Chapters and Regions to resolve through steady-state work. Occasionally, Red Cross national support would leave an expert in client casework and/or long-term recovery with the Region, to provide transitional subject-matter expertise. Sandy was way to big for this and we (New Jersey and New York, for sure) needed new Long-Term Recovery staffing from the Red Cross to keep these efforts moving.

- I learned – as noted above – I can lead multiple groups, staff in different roles, etc. without doing all those jobs directly, in other words, wearing all those hats at once. While delegation is certainly an important trait of leadership in any job or role, keeping all those moving parts – and people – in your own head is critical, as well. It should be a mental chess game, planning the next moves in advance as much as you can. I knew what did not go so well in Irene the year before, so I really focused on learning how to solve those past problems through any channels I could find (and I went looking everywhere I could – and made up new channels if I had to), sometimes even before they became current problems.

- I learned there is power in watching and listening to perceptive people (CM, BB, KC, SM, KS, AFB, AM to initial a few) – most of whom had vast, vast disaster experience – make positive changes in problem-solving. Lots of P’s there, right? Anyway, my point is that sometimes it is better to observe and absorb what the experts say and do first, and then take that intelligence and share it with others – not claiming it as your own, but rather making sure the fixes get done. When you put the idea in my head, and if I can run with it – I will run with it. And if you want to sponge from me knowledge, like SS absorbed wisely, I am happy to expound on what I know and what leadership lessons I learned.

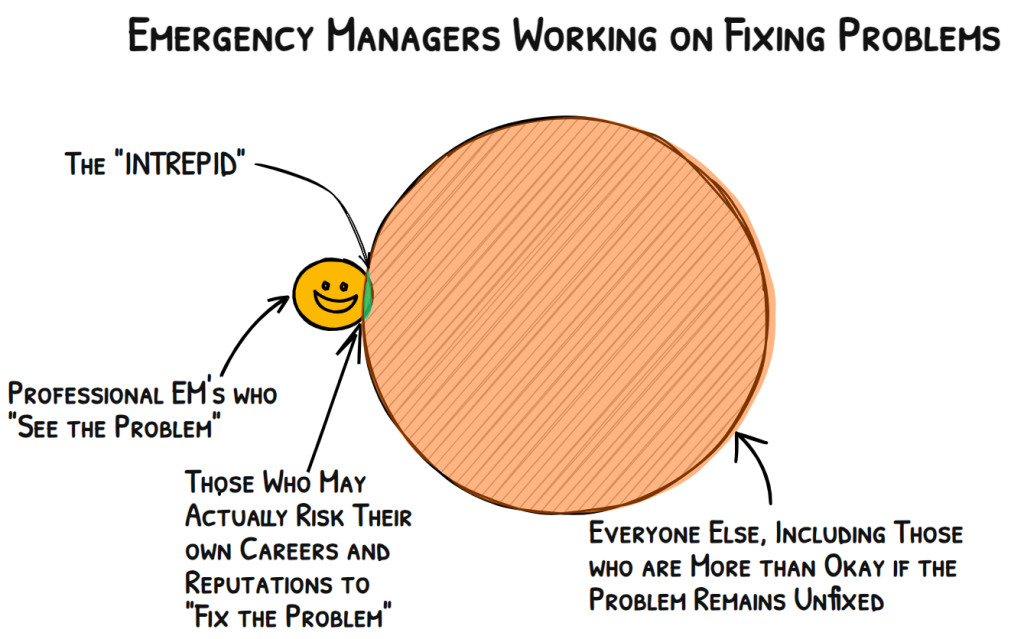

- I learned that any bureaucratic impasses or blocks can be overcome with enough perseverance. And, as a leader, if you see a problem you have an obligation to help fix the problem. And that fix might include having someone else get the credit (even if you do most of the work). I also learned that you do not want to be leading the group – or even representing the group – which is the cause of said impasses or blocks. Many years later, I would refine this concept of “see the problem, fix the problem” to include the fact that sometimes you have to decide whether to risk your own career and/or reputation and stand up for what is right:

Source: Barton Dunant. (C) Used with Permission.

Lessons Applied

There’s a Yiddish Proverb[1] which goes, “With money in your pocket, you are wise and you are handsome and you sing well too.” That was the case for the Red Cross with Superstorm Sandy.

- I helped the Red Cross establish its first Long-Term Recovery team (at least first time in New Jersey, for sure – someone can fact-check me on this ‘first’ anywhere claim) of paid staff to cover the entire state. They helped with the Long-Term Recovery Groups (LTRGs) which were being established statewide, manage additional Red Cross funding programs for housing repair and rebuilding, and more (see the light-blue box above from the Red Cross one-year anniversary blurb).

- My involvement with the New Jersey Child Task Force carried with me into my job at the state and beyond. Some of the folks on that task force still remember its significance and value into similar structures on future disasters. Make sure to include the needs of children in any role you have as a disaster leader.

- My seat on the New Jersey Housing Task Force, led by state officials (AM) was somewhat novel – the Red Cross had the opportunity to influence support for vulnerable populations, work with HUD and other groups on long-term housing strategic planning, and more.

- A continuously operating state-level VOAD is a critical need. Especially in New Jersey. I believed then – and still do now – that having a paid staff maintaining this VOAD – is the way to do it. And we have helped keep this going (both the Red Cross and me personally) since 2012. While I learned the lesson that I could not be in four places at the same time wearing four different hats; I applied that lesson by getting the VOAD to cover at least two of those hats. Maybe even three. The Red Cross blurb above notes grantmaking by the Red Cross (from record setting donations by the American Public – thank you – towards Sandy efforts by the Red Cross and its partners); one of those grants was the one I wrote for $250,000 to jump-start the NJVOAD. This was definitely one of those ‘Don’t let a good disaster go to waste’ moments.

- Both the NJVOAD and the American Red Cross are examples where you can apply leadership at different times, in different positions. When a disaster starts, you may need to lead from the front (like I did on Irene). Later, it may be better (for both your own wellness/sanity, and the needs of the public) to let others lead from the front, and take a middle role mentoring and providing direct advise to them, instead. And finally, there may be a point when others are leading from both the front and the middle, and you can step back – not away! – and quietly, thoughtfully, lead from the rear. Nothing says you cannot switch positions of leadership, if the needs present themselves. The risks and rewards are very different for each – but the self-satisfaction that you actually made – or are still making – a difference, remains the same.

- I learned all about FEMA policies – especially those involving NGOs – and where there were problems, I helped as much as I could to fix them. I am taking credit for getting the Donations Policy (9525.2) to now include Red Cross donated time and materials associated with Emergency Protective Measures (Category B), to count towards Public Assistance projects. This ended up being moot for Sandy in New Jersey, as Congress covered the state’s cost-share through the Sandy Recovery Improvement Act of 2013, but if they had not done that, we had more than $20,000,000 worth of donated hours and materials from all of the VOAD donated work, including that of the Red Cross. I also applied this experience in grass-roots insider-outsider change management in 2024, to get another FEMA policy fixed. You can read about the journey to do just that, at the book chapter I co-wrote with Jennifer Russell, RN, in 2024. I used the leadership lessons learned from Sandy, to redirect that proverbial fleet of aircraft carriers – and it worked.

- https://www.forbes.com/quotes/10401/ ↵

State Emergency Operations Center

Joint Field Office - used for coordinating a disaster between the state and federal officials. The Red Cross has designated roles on both 'sides' in New Jersey.

Office of Emergency Management

Disaster Relief Operation, also known as Disaster Response Operation. Term used by the American Red Cross internally to represent the temporary organization established in response to a level of disaster which exceeds $10,000 in expenses to the Red Cross.

New Jersey Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster

New Jersey Department of Children and Families

Recovery Support Functions

Federal Coordinating Officer

Voluntary Agency Liaison

Recovery Support Function Leadership Group

U.S. Housing and Urban Development Department

National Disaster Recovery Framework

Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster

Non-Governmental Organization, can include both for-profit and non-profit organizations.