8 765-12 – Hurricane Irene in NJ

Also includes Tropical Storm Lee, which came through the U.S. between September 5th through the 9th. Damages from both storms were combined into one Red Cross DRO, but seperated into two different FEMA DROs (FEMA-4039-DR for T.S. Lee in New Jersey).

Irene in New Jersey: FEMA-4021-DR

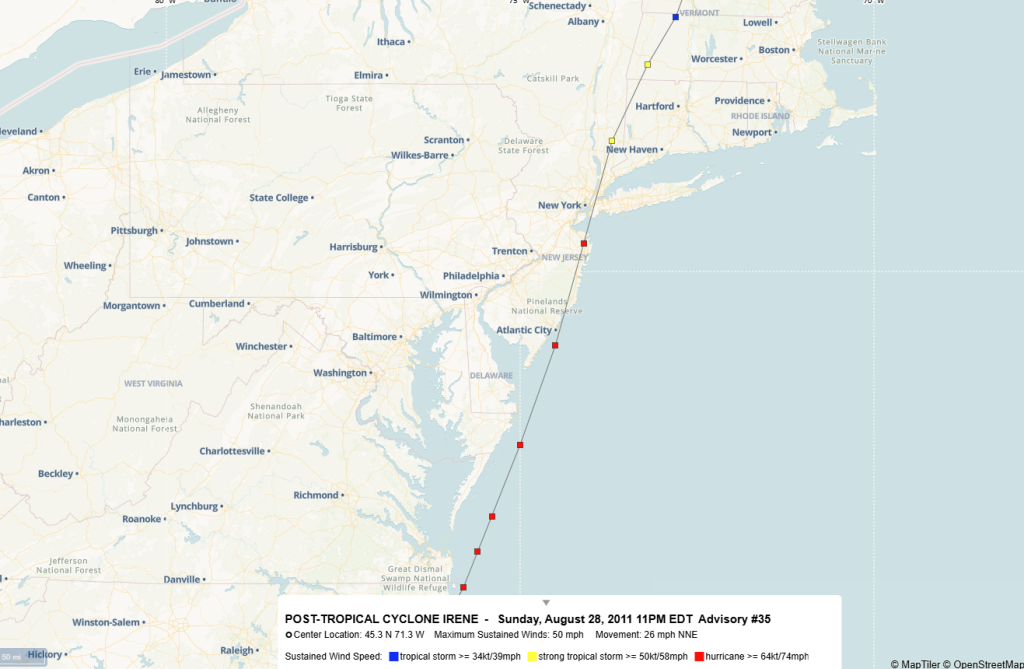

Hurricane Irene and Associated Floods of August 27–30, 2011, in New Jersey

The August 27–30, 2011, flood peaks rank as the peaks of record for 32 continuous-record streamflow-gaging stations with a period of record of 23 to 100 years, as the second highest peaks for 21 continuous-record streamflow-gaging stations with a period of record of 21 to 114 years, and the third highest peaks of record for 11 continuous-record streamflow-gaging stations with a period of record of 43 to 96 years. Several gages have documented peaks dating back to 1903.

About 1 million people across the State were evacuated, and every county was eventually declared a Federal disaster area. Property damage in New Jersey was estimated to be $1 billion. Governor Chris Christie declared a State of Emergency for New Jersey on August 31, 2011. After assessment of the damage by the Federal Emergency Management Agency, President Obama declared all 21 counties major disaster areas in the State of New Jersey on August 31, 2011.[1]

FLOOD SUMMARY – August 28 – September 9, 2011 Hurricane Irene and Tropical Storm Lee

AI-generated overview from Google Gemini:

Hurricane Irene in 2011 had a significant impact on New Jersey, primarily through widespread and severe flooding. Here’s a summary of its effects:

- Landfall and Impact:

- While initially assessed as a hurricane, it was later downgraded to a tropical storm upon landfall near Little Egg Inlet.

- The storm brought torrential rainfall, leading to major flooding across the state, particularly in inland areas.

- Coastal areas experienced storm surge and beach erosion.

- Flooding:

- Record or near-record flooding occurred on numerous rivers, including the Raritan, Millstone, and Passaic.

- Many roads were closed or damaged by floodwaters, disrupting transportation.

- Wind Damage:

- Strong winds toppled trees and power lines, resulting in widespread power outages.

- Many homes suffered structural damage from the winds.

- Statewide Effects:

- The storm led to the largest coastal evacuation in New Jersey’s history.

- It caused significant damage to homes and infrastructure, with costs reaching approximately $1 billion.

- Power outages were very extensive, effecting over 1 million customers.

- President Obama declared a major disaster for New Jersey.

- Rainfall:

- Rainfall amounts reached as high as 10 inches in some areas.

- The already saturated ground from prior rainfall exacerbated the flooding.

In essence, Hurricane Irene’s primary impact on New Jersey was through the devastating flooding caused by its heavy rainfall, which significantly disrupted daily life and caused widespread damage.

Irene brought multiple hazards to the entire state. There was wind damage – large trees falling on roads, powerlines, homes – and of course flooding damage. The flooding damage was significant. It was much more than coastal flooding from the Atlantic; communities along the Delaware River saw flooding, as well. So did inland communities[3], when the tributaries and streams overflowed into streets, backyards and worst of all, basement apartments.

This was not my first Red Cross response to a major flooding incident in New Jersey, but it was my first in a command position.

Lessons Learned

Paradoxes of the Red Cross Response

I had already been indoctrinated in the concept of ‘home rule’ in New Jersey. This is where each town, each county, and even the state itself chooses to try to go it on their own. In some communities when disasters strike, this can be a benefit to their residents when that level of government is on the ball, knows what to do, and most importantly already has the resources to support their resident’s needs. This way, those residents are prioritized for their life safety and incident stabilization and move towards recovery much quicker. Towns (technically ‘municipalities’, since ‘town’ is a legal term for a specific size and style of government. New Jersey has boroughs, townships, towns, and cities – and all of the land is incorporated into part of one municipality or another. There is no unincorporated land in New Jersey. This means quite a bit of governance and politicians, but not necessarily Emergency Managers.

When a town can fully support itself before, during, and after a disaster, is a very rare occurrence. Especially one of size and scope like Irene. When it comes to smaller, recurring disaster such as home fires, the tactical support is generally in place for the response work within each town. Local first responders (police, fire, EMS, etc.) are there for life safety, incident stabilization, and property protection. New Jersey has over 1,000 of these each year with major damage to the home – most of which require the residents to evacuate and move somewhere else. Some towns have a support network to help the uninsured (or underinsured – a much more frequent problem), but when it is a multi-family home or the town is ambivalent (I’m phrasing this nicely) towards its taxpaying residents, that is when the Red Cross can – and usually does – help. This can range from financial support for the family for lost items, food, or shelter – generally enough for a hotel stay of up to three nights. In 2024, it was around $500 for a family of four. If the number of impacted families from the disaster (generally all hazards where the emergency responders order evacuations except for landlord-tenant issues, with a few exceptions) is greater than ten (10), the Red Cross switches to a sheltering model, which can last much longer than the three days. Feeding is included, and there is no cost to the residents or the town for this, as well. Candidly, it is more cost effective to provide food and volunteers for many more days of support of displaced residents, than to spend thousands of dollars on hotel stays. Now, COVID-19 put a different spin on this model in 2020 and 2021. More on that in the COVID-19 chapter.

One would think that this model can work for everyone, but there are in fact challenges on both ends. Here’s the paradox: Towns do not want to be in the sheltering business for the ‘everyday’ incidents, but they also want their own shelter – run and paid for by the Red Cross, of course – when the big ones happen, like wildfires and hurricanes. While the Red Cross in most states – including New Jersey – can support the staffing and logistics to support a single shelter during an incident (in fact in New Jersey we can ramp up to three without any notice fairly easily), we cannot support a shelter in every one of the 565 municipalities across the state at the same time. So we go to a regional model, which is county-based, supporting up to two shelters in each of the 21 counties (plus a few more – more on that in the next paragraph). Now mind you, in each of these sheltering scenarios – the multi-family fire and the hurricane, the town where the shelter is still has to produce the shelter site itself (most times schools or community centers) and they still need to perform governmental responsibilities for security, social services, housing relocation, and more. When there is low media attention, there is low political attention. And it can become another paradox, when the town uses a school for sheltering its residents with kids from a disaster and then needs to close that shelter because the school needs the space (usually the gym). Or worse: the school is concerned that the residents in the shelter are ‘unsavory’ (again, being nice) and a threat to the students. Nine times out of ten, it is the families of the kids in the schools, including the kids themselves.

During Irene, I was a paid employee with the American Red Cross in New Jersey. We had three separate regions in the state, and I was the deputy manager for disaster services (our version of emergency management) for the central region of the state. My boss GH – who I have mentioned before as being my best Red Cross mentor – was the Red Cross’ lead disaster person to the State of New Jersey. GH is from Georgia and even with more than 20 years of experience as an EMT in NYC, she still has that sweet but fiery Georgian accent. She was also at the time a Red Cross Level 5 job director from her many years of serving at tornadoes, floods, hurricanes, etc. This is the equivalent of a Type 2[4] Federal Coordinating Officer.

We had talked about this size of a storm, during Red Cross and other training classes and exercises. Mostly via a New York City-driven model – “What if a major hurricane hit downtown Manhattan? Would New York City flood like New Orleans?” That sort of thing. We received the (then) usual 120-hour warning for Irene from the National Weather Service and started planning with the state and other groups (Salvation Army, 2-1-1, our state’s Food Bank, etc.) and the NJ Governor asked for and received Federal Assistance through a pre-landfall emergency declaration. We did our best to organize the volunteers to get ready, but because this storm was not slated to directly hit New Jersey as the first point of landfall, New Jersey was not in the spotlight for media or the public’s attention. As I noted before, New Jersey is also a home rule state, where each of the counties is responsible for sheltering their own residents, or leaves it to the towns. We had to coordinate with each county (some wanted shelters in advance, some were unprepared for this storm, some were against shelters, etc.) and also with the state itself who was coordinating with federal officials. We tried our best to be proactive – but there is never enough time (or meetings that end with actual agreements to shelter) to coordinate in advance all the right things to do for a storm this size – so we fall back on being reactive – one step behind usually – we wait for someone to ask for assistance and scramble to put it together with the staff, resources and equipment we have on hand, and then ask for outside help as soon as possible. I believe this is a lesson I learned but was not able to successfully apply during my tenure as an employee at the Red Cross.

One good thing about New Jersey is that after 9/11, the state knew they needed a better State Emergency Operations Center (SEOC) and combined it with an intelligence fusion center, forming the Regional Intelligence Operations Center (the ROIC, pronounced like “the rock”). The day before landfall, GH and I headed to the ROIC to coordinate Red Cross support for Hurricane Irene. It would be an overnight stay for me on the floor of the main operations room on a cot next to the volunteer from the Salvation Army.

Hurricane Irene made landfall in North Carolina on August 27, 2011 then headed back out to sea, to roar up the Atlantic coastline – heading right for New Jersey. Three counties issued mandatory evacuations, a reverse lane process on our major highways was implemented and Atlantic City had its first mandatory evacuation in history. The state, in its own description of what happened before, during and after Irene hit, describes the evacuation and sheltering aspect as:

Seventeen New Jersey counties opened shelters to support the evacuees. The night prior to Hurricane Irene’s predicted arrival (August 27/28) there were 16,191 registered evacuees supported in shelters across the State. County shelters supported 13,864 evacuees and the State-sponsored shelters supported 2,327 Evacuees (NJOEM, 2012).[5]

What this doesn’t tell you are the twists and turns of the real story of this evacuation effort.

We were on the ROIC’s operations floor at our desks (three or four spots for each Emergency Support Function – the Red Cross and the Salvation Army are two of the only non-governmental organizations to have assigned seats at the ROIC, in ESF#6 – Mass Care) – it’s a really cavernous room, and the hub of the state’s command and coordination for any type of major incident. In many ways it reminds me of a casino floor – no windows and lots of screens (with flashing monitors, not slot machines). It was full of folks from the various state departments and is led by the New Jersey State Police, who manage Emergency Management in New Jersey. We were getting squared away for county-level sheltering – one or two here, three or four there – nothing too big, shelters for around 250-300 people max. This was our plan, our usual sizing for spring flooding events – please recall, we were not prepared for the same type of hurricane onslaught that states like Florida or Georgia regularly receive from Atlantic storms.

Then we learned that 10,000 residents of Atlantic City were already evacuated on buses and were headed all over the state. Like right now.

And they needed a place to go for the night, before they would be returned on those same buses to Atlantic City, if they could. GH was getting this news from the lead from the state police and the lead from the state’s Department of Human Services (that agency is the state lead for ESF#6) near our desk area; when from out of a room somewhere in the back, came the Director of the state’s Office of Homeland Security and Preparedness (not part of the State Police, but a separate entity, reporting directly to the Governor).

Suddenly there was a separate evacuation plan which none of us in the room knew about – including using stadiums and arenas across the state to house these 10,000 people – and it was being implemented now. Like right now.

Soft, reserved sweet GH suddenly became fiery GH – and was aimed right at the Homeland Security Director: “Where the hell do you think you are going to put these people? Why are we hearing about this plan only now? What do you expect us to do? What were you thinking?”

Very quickly, that big giant room filled with all those people – many of them seasoned state troopers – became very, very quiet.

GH had stood up for the people affected – toe to toe (and actually nose to nose, wisely standing on a higher step in the auditorium-like floor) with that Director. In the end, the National Guard and other state groups – including the paid staff from the Homeland Security group themselves – helped move and keep safe all of those 10,000 people in Reception Centers (not shelters) as the Homeland Security Director wanted (he was speaking directly for the Governor really, and btw they had not coordinated this plan with their own State Police either – that is a much longer story for another time, and to be told by someone else besides me). The Red Cross provided volunteer advisors to make sure humanity and dignity were preserved at all the sites used by the state and counties. It was a strong lesson for us that we have to be flexible in the end to make sure the constituents are best served – and sometimes our best plans get thrown to the floor (remember no windows at the ROIC’s main room for us to throw anything out of).

I also learned that volunteers from other states need to know how very differently we do things in New Jersey. We had to teach them how to make left turns (we use jug handles here), how to let someone else pump your gas for you (still the only state where you cannot do that yourselves!), and more. I learned in my command work that if you have Type A personalities working for you, and you are also a Type A person, you are going to have some clashes. I learned that incident commanders do not take a victory lap – even after years or positive after-action reports. The success comes in either keeping on at the high level you have achieved, or possibly getting promoted. I learned the value of lifting great leaders up and supporting them during and afterwards (through positive evaluations, which help them get promoted). I learned that team players work best in teams, lead via hands-on leaders at the front.

I learned that there are other leaders who need your help to lead themselves. The Red Cross has a partnership in New Jersey with a state-led, county-managed mental health volunteer group[6], to support disaster mental health in large scale incident shelters across the state. One of the tasks I had during Irene was to help coordinate these folks to have access to the shelters run by the Red Cross. Again, with volunteers from other states – most of which do not have ‘outsiders’ coming in to support mental health, this was a tactical challenge. One that had to be overcome. The lead for this at the state, AFB, sat right next to me at the ROIC, so I got first-hand knowledge of where there were gaps in support – and where we (the Red Cross) needed to change our ways, for the benefit of the clients. I also learned that AFB had two daunting tasks: First, managing the methadone support for patients who now did not have access to their clinics because they were in shelters and possible unable to get to their dosage. Second, she had to start writing the SAMHSA grant for recovery mental health support (something almost always granted, when a Presidential Declaration is made – but you still have to manually apply as a state) now, so it would be in place at the end of Response and the start of interim or short-term Recovery. I learned that both of these would become checklist tasks, which while not the responsibility of the Red Cross, did have Red Cross impacts. Both of these were much easier to manage for Sandy the next year, because of the lessons learned during Irene.

I learned that if bad news needs to be delivered to the public, that falls on you. I stepped out of our Red Cross district command center twice during Irene to go and close shelters, personally. Once everyone can return home – or go elsewhere – they need to. When people become more comfortable at the shelter and they can go somewhere else, that is when we close them down. These are some of the disaster tasks that leaders cannot delegate. Shelter managers are taught to focus on closing the shelter (meaning make sure everyone is supported through casework for transition from Response into Recovery), as soon as the shelter is opened. It helps them tremendously to have someone else be the ‘big bad guy’ who is saying this shelter has to close.

Lessons Applied

- We had some very significant and very fiesty (nice words by me, again) meetings with local and county Emergency Management officials after Irene. This is when they would insist they ‘needed’ their own shelters – again, staffed and funded by us – and we would tell them that was not possible. This is where the regional sheltering really solidified. Some counties balked at this – and decided to ‘go it on their own’. One big factor was the override of home rule during disasters: if the Red Cross runs a shelter (manages or co-manages), the rule is anyone impacted by that disaster is welcome to come to the shelter. That did not work for some counties who wanted to exclude anyone who was not their own residents. This also translated into some counties not wanting to support non-citizens. And the mass movement by the state of Atlantic City residents across the state to shelters in many counties that the county would have preferred to use themselves, certainly did not help. One county was even openly against any future evacuations from out-of-county into theirs. They planned roadblocks to prevent buses from crossing county lines. This county – to this day – still does not coordinate with the Red Cross on large scale incident response. We were still scheduling these meetings into 2012, when Sandy hit that next year after Irene and Lee.

- I learned quite a bit about damage assessment from the governmental view, from Irene. I had done preliminary damage assessment (neighborhoods) and detailed damage assessment (each home) from prior flooding incidents and had a good team supporting me in my command of the seven counties I had, during Irene. Still, I learned that there is always something missing – some community who thought they could go it on their own and not ask us for help. Some community who did not have a good relationship with the state (or maybe even their ambivalent county) for support, as well. Those residents get the short end of the response and recovery stick. And there is no reason they should. I applied this lesson in Sandy and future responses by looking at the totality of damage assessment reporting: you have to get to 100% of sites reviewed and then go back to critical areas again to double-check. You need to absorb all that intelligence and act on it immediately. I learned that even leaders have to question authority. This lesson applied, would come back and bite me, years later.

- As noted before, this disaster for me was a chance to lead from the front. As we had been organized for Irene as (what is now called) a District model with three seperate Red Cross operations running in the state, under one statewide coordination for logistics including staff support, finance and administration and command (including public information officer/public affairs coordination being centralized at the state level) for the ‘middle’ level, and of course our National Headquarters performing command from the ‘back’ (as it continues to do now). I may have applied this model of leading from the front, unknowingly at the time.

- I was also supporting our statewide Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster (NJVOAD) group along with GH and the leads from the Salvation Army, Community Food Bank and NJ’s 2-1-1. We all knew that these level of disasters typically come with all of our national organizations trying to fit their square pegs into our round holes. In other words, impose national doctrine and processes to override what is in place at the state. This may work for states with weak VOADs (or those with no VOADs at all), but not so in New Jersey. This was a lesson applied for me, during Irene – which would pay off during Sandy and beyond: Don’t upset the applecart. If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

- They may say ‘Don’t Mess with Texas’, we say ‘Don’t F with Jersey’.

[1] https://www.nj.com/news/2011/08/hurricane_irene_damage_is_stag.html#

- Watson, K.M., Collenburg, J.V., and Reiser, R.G., 2014, Hurricane Irene and associated floods of August 27–30, 2011, in New Jersey: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2013–5234, 149 p., http://dx.doi.org/10.3133/sir20135234. ISSN 2328–0328 (online) ↵

- https://www.nj.gov/drbc/library/documents/Flood_Website/Irene-Lee2011.pdf ↵

- https://www.nj.com/news/2011/08/hurricane_irene_damage_is_stag.html# ↵

- https://training.fema.gov/emiweb/is/icsresource/assets/incident%20complexity%20and%20type.pdf ↵

- New Jersey Office of Emergency Management. (August 17, 2012). “Resources for Journalists Regarding the One-Year Anniversary of Hurricane Irene”. Retrieved from https://www.state.nj.us/njoem/media/pr081712.html ↵

- https://www.nj.gov/health/integratedhealth/services-treatment/drcc_credentialing.shtml ↵