Not quite a secret, one of the world’s largest and most important scientific laboratories is hidden up a back road in a rural area of New Hampshire. Sharing the White Mountain National Forest with tourists, vacationers, hikers, and swimmers, a team of scientists is doing research in the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest. They are trying to solve the riddles of water and forest management by discovering how a Northeastern hardwood forest ecosystem works.

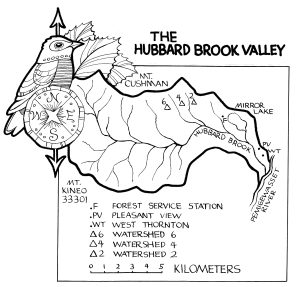

The Hubbard Brook Forest is an outdoor laboratory. It is shaped like a bowl five miles long and three miles wide. Ridges rise to make the uneven sides of the bowl. Mt. Kineo is 3,330 feet, the highest point on the ridge. Valleys 750 feet above sea level make the bowl’s bottom. Many small mountain streams drain areas of twenty to four hundred acres and flow into Hubbard Brook, which then joins the Pemigewasset River at West Thornton. By this route the water from 7,600 acres of federal forest land flows toward the Atlantic Ocean.

To visit this experimental forest, you turn onto the Mirror Lake road that joins U.S. Route 3. You pass the lake and then, leaving the paved road, you wind upward into a typical New England broad-leaved hardwood forest. From a high viewpoint you see leaves melt into a solid green quilt that covers the softly rounded peaks, slopes, and narrow valleys of these old, old White Mountains.

Now the forest air is cool, barely stirring. The morning sunlight filters through the leaves, making you feel a bit like Alice, suddenly and unexpectedly stepping into a green wonderland. Entering a Northeastern hardwood forest in the summer is like taking off a sweater, putting on green-tinted sunglasses, and inserting earplugs all at the same time.

As you drive into the forest, the noise of your car engine sounds out of place and disrupts the peace of this place. When you turn off the engine, a sudden quiet makes you feel removed from the outside world.

Be careful when you get out and lean against a tree. Eastern forests have deceptive trees. Outside, a tree may look whole and strong, but insects and woodpeckers may have opened holes to invading molds and fungus that have rotted the tree to its core. Lean against such a tree and it splinters, leaving a jagged stump and a branchy broom, with you lying on the hobblebush vines at its feet.

You stand on the past. Season after season leaves have fallen and piled up. They decayed and were turned over and under, thoroughly mixed through the passing years by worms, insects, grubs, small mammals, amphibians, mites, and reptiles that burrowed through leaves and soil, eating here and discharging there. These animals made pathways for air and water that further broke down leaves, limbs, and bark. A deeper soil was created.

The soil supported a forest that became a home for Native Americans. For thousands of years, Native Americans used the White Mountain forests without changing the natural surroundings. Their numbers were few. Nature was able to grow over and around their scars. The land kept its natural communities.

But the forest you see is not the one the Native Americans used so sparingly. After 1763 and the French and Indian Wars, towns grew and settlers cut forests to make pastures for sheep and cows. They cleared land for crops—corn, potatoes, and oats. A lot of timber was cut for lumber. Hemlocks gave tannin for tanning hides. Trees changed into furniture, houses, and many other wood products as well as firewood.

In less than a hundred years, most of the primeval forests had been cut. One half of New Hampshire was under cultivation.

Use quickly depleted the fertility of the thin soil. The land was not good enough to compete with the naturally richer lands opening on the Western frontiers. Dairy and sheep farms failed.

A sawmill, a tannery, a bottling works, a dance hall, a boys’ camp, and tourist cabins appeared on Mirror Lake’s shores at one time or another in its history. So Mirror Lake had periods of pollution. But use was not so great that the little lake wasn’t able to clean itself. It has managed to stay a high-quality forest lake with clear water, little decaying plant life, and low nutrient levels. The question is: Will it stay clear under today’s high use?

This forest is as important to people today as it was to the Native Americans and pioneers of yesterday.

The life of a forest and of a human community depends on water. Knowing this, the United States Forest Service has long been the keeper of our watersheds and our forests. States, as well as our national Government, have saved much of our country’s forests for the welfare and benefit of all the people.

A forest watershed is like a reservoir that holds rainwater and lets water pass gradually to streams and rivers which serve communities along their flow to the ocean. Because trees are cut for lumber and other products, the U.S. Forest Service wants to know the best way to harvest a forest and control the water that enters streams. What happens to the water-holding ability of the forest when trees are cut in different ways? What happens to the amount and purity (quantity and quality) of water that flows through cutover forests? Trees lose about 40 percent of the water they receive. If the trees are cut, what happens to this water that would otherwise be going into the air through transpiration—release of water from the leaves and evaporation by the sun? Would more water flow in the streams?

To answer these questions and predict more accurately the amount and quality of water reaching downstream cities, towns, and farming communities, the United States Forest Service decided to experiment. They hoped to learn the best ways to manage a forest for the many uses that people demand of it—recreation, drinking water, irrigation water, manufacturing water, timber products, soil conservation, and so forth.

The Forest Service wanted to learn several things. Where did the water come from? How did it move about? Where did the water go and where was it stored? What water was left after all the water-needy parts of the forest had gotten their share? How much sunlight—solar radiation—came into the forest soils? What were the uses of the forest plant cover and what did it give back to the atmosphere?

In their outdoor laboratory the Forest Service hoped to find their answers. They chose this spot because Hubbard Brook’s drainage is typical of New England’s watersheds. And the boundaries of the watershed bowl kept the water in Hubbard Brook streams. An impervious igneous rock layer—a rock layer with no cracks or holes for seepage—lay below a porous or spongy soil. Water could escape only by evaporation or in the streams.

This combination made a perfect spot for experimenting. All the minerals dissolved in water that came into the forest, or added by weathering or leaching, and all the minerals that went out of the forest could be measured, along with the quantity of water. Water went through the porous soil easily and flowed down the uncracked rock. Heavy rains quickly showed up in the streams that drained the Hubbard Brook basin. Researchers could watch rising floodwaters turn their quiet fishing stream into a roaring lion.

Dr. Robert Pierce was responsible for all the research in the forest. As director of the research projects, he realized the importance of learning everything there was to know about the forest laboratory. He wanted to know the changes in the woods from hour to hour, day to day, month to month, year to year.

He knew that a lot of research would be needed to get the most benefit from the forest experiments that were planned. He was open to new ideas and ways to solve problems. When he said “yes” to two ecology professors, the first total ecosystem study ever tried—a “prototype”—began. The Hubbard Brook ecosystem study was a first on two counts. Such a total study of an entire ecosystem had not been done anywhere else. And cooperation between the Government and private institutions and individuals on a single ecosystem study was also a first in the United States.

The study began slowly. Gradually informal science teams, individual researchers, and Government foresters and scientists worked together to better understand the functioning of an ecosystem. Here scientists from many disciplines could study the links in the endless chain of nature.