As projects at Hubbard Brook were completed, more written reports lined college library shelves. Newly turned out researchers left the Brook. Some members of the team began a lifetime of research. Others became science teachers and researchers at universities, small colleges, and high schools.

Several Hubbard Brook “alumni” began newly created jobs in the outdoors as field researchers for private firms and Government agencies. A few students had the opportunity to become ecology synthesizers, writing ecological reports for the new and old organizations required to make impact statements to the Government. The “synthesizer” takes all the field research data and brings the information together in a meaningful way. Synthesizers analyze the facts and write reports that offer recommendations for future actions. Synthesizers appeared to be in demand.

Many qualified researchers do not care to be inside behind a desk all day writing impact statements. Some ecologists avoid these jobs because they feel pressure might be put on them to hurry a report to meet deadlines. They do not want to be put in a position where they might be asked to use data to support private business need or agency prejudice. The ecologists want to be free to make as accurate ecological observations and judgments as they can. Individuals in conflict with their ethics or principles could be unhappy people and discontented employees.

Business, government, and individuals may have to put first what is best, in the long run, for everyone. Science, with its data-gathering and analysis systems, is simple compared to the difficulties in changing the habits, life-styles, values, goals, customs, ethics, and laws of people. It is easier to discover a floodplain than to get people to move from an area that is repeatedly flooded.

New steps in communication made it possible for the originators of the Hubbard Brook project to piece together a unified picture. Weekly telephone calls between Dr. Bormann and Dr. Likens kept each informed of new projects under their direction and the happenings and findings of research that was under way. Each new project idea was discussed and worked out with one of the three men who had started the ecosystem research.

A meeting each spring of all the people working on projects in the Brook allowed them to become acquainted with each other’s objectives and methods. During the year meetings were held. Progress reports were given. As papers were written, copies were sent to each scientist working on the project. Everyone had a chance to make their comments.

The Hubbard Brook project resulted in a better understanding of an ecosystem. It developed a procedure for including individual projects as part of one whole study. Students and established researchers, given freedom to follow their own interests and choose their own projects, worked diligently and with dedication. Many workers were able to contribute to the accumulation of project data. Hubbard Brook successfully broke ground in cooperative ecosystem study, using nutrient cycling and energy flow research to link together the many sections of the chain of nature.

As an ecological research station, Hubbard Brook became an early model for other research areas in the U.S. and other countries. The station received many visitors interested in getting ideas for running their own ecological projects. A much larger grassland project in the Western United States was patterned after Hubbard Brook in some ways.

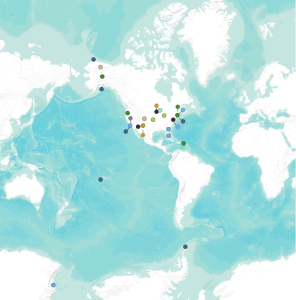

And, in 1980, the National Science Foundation created a network of long term ecological research stations (LTER) to conduct research on ecological issues that could cover both long time periods and large geographical areas. There are now 28 such stations, spanning ecosystems as diverse as the Arctic, the Antarctic, the Everglades, Pacific Islands, and everything in-between.

(from NSF LTER Network website)

If enough is learned about many different habitats and the functioning of their ecosystems, scientists may be able to predict what is happening to the whole earth ecosystem. They may be able to predict what can happen according to the different treatments people might give our world.

Governments may ask for the ecologist’s help in managing wisely earth’s resources to best ensure a healthy, adequately fed and housed population.

Another result of the Hubbard Brook study was more questions.

After departing researchers had fitted their pieces of the Hubbard Brook puzzle into place, new puzzle players took their places. New initials appeared in the freezer and refrigerator and on the numerous boxes crowding the kitchen. New faces appeared around the dinner table, the research tables, and in the laboratories and woods. A new “Bob” took over Dave G’s pit, the dungeon in the basement.

New steps to solve new mysteries began each summer. Three researchers used scuba equipment to search the bottom of Mirror Lake for carnivorous plants – macrophytes. Patiently, Bob cleaned the green plants, placed them in aluminum foil, numbered them with a black marker and placed the twenty species he had found in the freezer. What kept them from filling the lake? Would he find their limiting factor?

How much carbon dioxide exchange occurred between the lake and the air? Bruce and his silver-painted floating dome hoped to find out.

Did wax paper and shoe boxes help Sally collect bird stomach samples after encouraging the bird to throw up?

How many species of mayflies did Sandy discover?

Did Jo Ann find the piece of the puzzle that showed why more nitrogen was lost from the clear-cut areas? Did her procedure using a hypodermic needle to inject gases and take gases from rubber-stoppered baby-food jars help her discover the nitrogen fixation rate by free living algae and bacteria? Did it help measure the rate of nitrogen fixation in the soil of a watershed?

Would the stacks of Petri dishes with colorful fungi and the floating automatic water samplers help Marilyn total the respiration of everything in the lake?

Did Judy work out the phosphorus budget for her stream? How much phosphorus went in and how much came out of the watershed she studied?

Time, as well as measuring, recording, and analyzing data, might give them their answers.

2013 — More Endings and Beginnings

In the 50 years since the Hubbard Brook Ecosystem Study was started, literally hundreds of undergraduate and graduate college students, post-doctoral associates, and science technicians have worked and trained at “the Brook” and contributed their insights to increase our understanding of how this complex ecosystem works. Together they have published more than 1,420 scientific publications, 11 books and 8 monographs, as well as nearly 100 Ph.D. dissertations and 68 Master’s theses. Right now, around 40-50 researchers from 20 or more organizations are doing work at the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest. And they continue to find new, important questions to research. Some of the major areas of study that have emerged since the first edition of this book include questions about changes in climate measured at Hubbard Brook and their effects on soils, birds, and other parts of the ecosystem, questions about the fragility of northeastern forests and their ability to recover from the effects of acid rain, and continuing questions about the factors that influence the population of birds, particularly migrating birds, in the Hubbard Brook forest.

See the Resources section for more readings and for links to opportunities to explore and apply for yourself information that has been developed at Hubbard Brook.