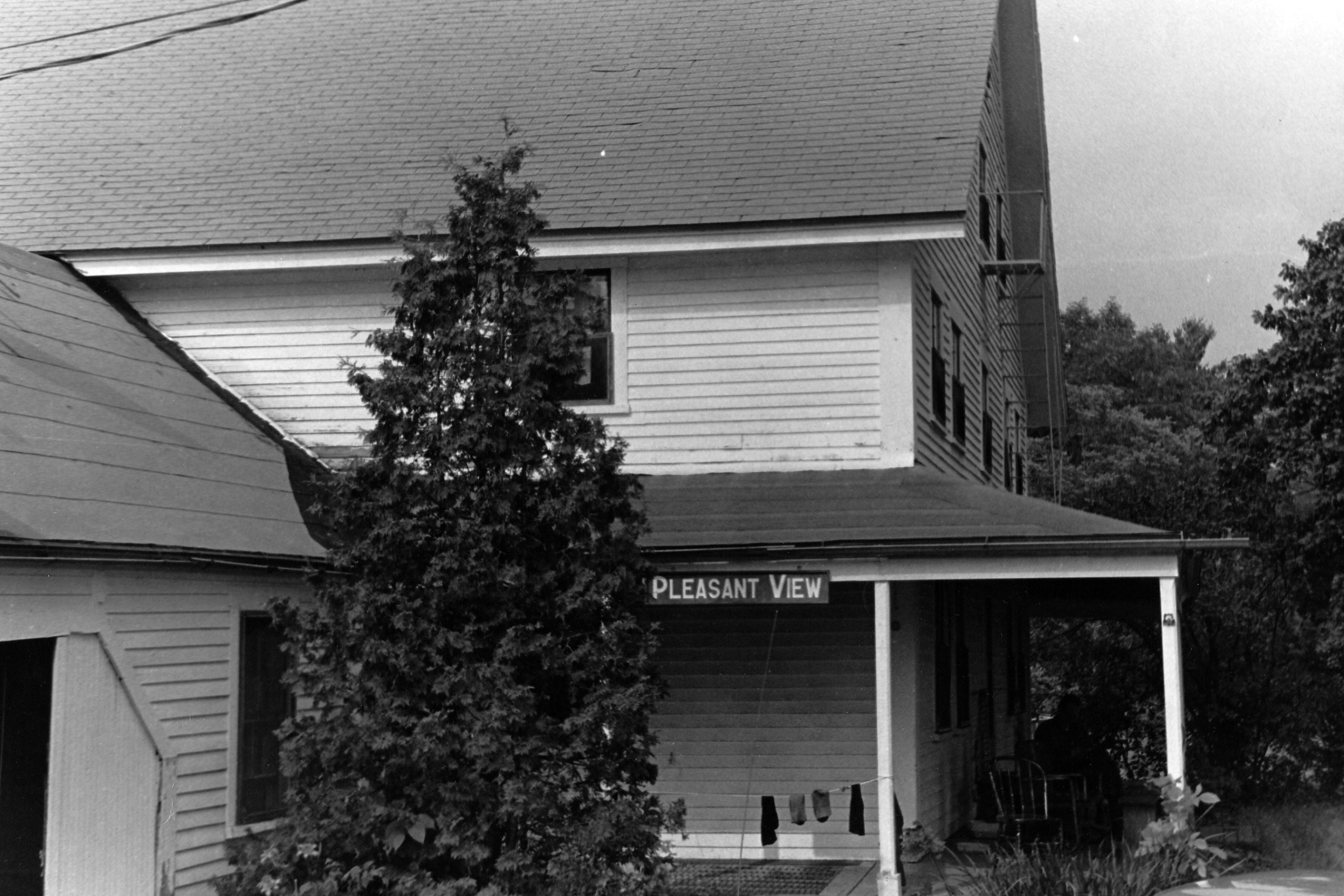

Where to put all the people needed to piece the ecosystem puzzle together? The answer — a big old farmhouse. Pleasant View was the summer home for the researchers. New arrivals slowly eased their cars up the narrow, blacktopped lane into a tire-rutted dirt drive. Before them rose a huge, three-and-a-half-story white clapboard house. The long, wide porch beckoned them to find a chair, rock, and enjoy the pleasant view of the White Mountains.

Two hundred years old in parts, the house had its own unique history. Hidden plates for counterfeit money, an underground railroad station for escaping slaves, tavern, resort, rooming house, restaurant, tourist home, family home, and research station were all chapters of its past. The home had been in Henrietta’s family for a hundred years. She rented it to Dr. Likens and Dr. Bormann and in a motherly way cared for “her boys and girls,” as she called the young researchers. Her home was a short distance away, and she frequently dropped in to leave a sample of her latest baking, a cashed check, laundry, or an invitation to her famous turkey dinner.

Indeed, Pleasant View was a pleasant place to be. The new fifty-year-old forest softened the rounded humps of the mountains. Within the wide circle of mature and sapling white pines, balsam fir, white birch, and aspen, tall green grasses were dabbed with spots of purple vetch, red paintbrush, and orange filagree. A broad patch of grass was mowed for a lawn in front of the house. Two one-hundred-year-old trees, an oak and a maple, shaded the front yard, the flagpole, and a camp trailer. The aspen leaves with their twisted stems moved with the slightest air movement, retaining their coolness.

In the evening, from the porch, researchers watched the aerial display. Swallows dipped for their dinner. Bats darted after insects and hid their nesting young between the wall of the old house and the attached garage. Their squeaky cries mystified and stirred the researchers to investigate.

As the sun set in the west behind the house, the darkness brought fireflies, stars, and a waxing or waning moon over the field.

Inside, the house had been modernized through the years. Seven fireplaces were walled in and replaced by a basement oil furnace. An oil burner heated the living room in the winter. And two gas stoves with trash burners in the kitchen cooked meals and took the chill off cool mornings and rainy days.

Kerosene lamps had been replaced by electric lights in 1920, and the outhouse was abandoned for a downstairs bath in 1950. Later an upstairs bath was added. The front door opened into a large entryway and a flight of stairs that led to numerous bedrooms. Five downstairs doorways led to the parlor, two dining rooms, the bath, and two attached bedrooms. The busy kitchen was off the dining rooms. The back porch was turned into a lab and looked out on a forty-foot trailer lab.

The interior of the house was a strange mixture of antique furniture and recent research. The parlor, with gray paint, faded red-flowered wallpaper, and a linoleum carpet over prized wide floorboards, was the relaxing room. Here researchers read, played cards or checkers, or made music on the piano, violin, and flute. They sewed, wove, knitted, conversed, and listened.

The twin dining rooms had once served tourists meals. Now they held research clutter. Family pictures and paintings decorated the walls, while a china closet still enclosed Henrietta’s glassware and dishes. But the yellow and pink plastic tablecloths covering two sturdy oak tables were never set with the pretty dishes or flower centerpieces—they were littered with research paraphernalia. Collecting bottles, cotton wads, piles of papers, files of records, journals stacked high, binoculars, typewriters, calculating machines, reprints, microscopes, scales, glass vials. Tape recorders, maps, charts, index card files, and empty fruit cans all claimed their places in the dining rooms.

The kitchen was another place where the crews could socialize. Two stoves lined one wall. A sink and small counter fitted one side of the dining doorway, a dish hutch the other side. The middle of the room was filled by two long tables. A refrigerator and phone table took up a remaining wall. A small pantry off the kitchen held pots and pans along with researchers’ grocery sacks and boxes, all labeled with big black letters: TB, DM, DZ, DH, TS, FS, etc. Initialing everything was the way the researchers identified their own materials. Refrigerators held containers with the same black letters.

How did many people working under the grants of several principal investigators live in one house with one kitchen and two baths? With difficulty and a sense of humor!

One cook would have had an impossible job, never knowing how many were coming to a meal. Researchers’ schedules all differed. The number of invited scientific groups with pup tents in the fields changed too. So all researchers took care of their own meals. A few people with compatible schedules joined forces to prepare, cook, eat, and clean up. If a researcher’s stomach growled and the kitchen was empty too, that was a good time to fix dinner. If the kitchen was full, he or she would just have to wait for a space and a pan.

Although this was not intentional communal living, it sometimes appeared to be. The researchers suffered some of the problems of such living groups. Lots of people make lots of trash—getting the trash to the local dump was a problem.

Everyone took their turn at nightly kitchen clean-up jobs. Muddy field boots made daily hall and stair sweeping a goal. Before the summer work closed, everyone joined in one grand housecleaning day.

Bathrooms were another problem. Waiting turns was not always as easy as waiting to use the kitchen. Everyone scrubbed out their own bathtub ring and tried to keep the floor dry. When the well was very low during a drought, people swam in the lake to get clean. Most of them swam in the lake every day anyway, so this was not an inconvenience. Henrietta solved the water problems by drilling a new well for her “boys and girls.” But a new well didn’t help the cities downstream that depended on the mountain river waters. We all take water for granted until we don’t have it. Maybe the tree cutting experiments would show us ways to keep an even amount of water flowing down the rivers all year.

When it rained, more people stayed in the house and caught up with their bookwork and record-keeping. Once it rained almost solidly for four weeks. But the young, active minds could not be dulled by indoor monotony. The researchers invented. The kitchen was often the scene of their creations.

Sitting in the back dining room, Dave Z., an undergraduate student, rocked and read to Bernard, Dr. Bormann’s son, who listened intently to a recipe for coffee cake.

“Heh, that sounds good. I wonder how much that costs to make? Probably about the same as half a cake. Look in our book and see,” Dave said.

Sheryl, daughter of a resident scientist, walked over and peeked at the figures in their spiral notebook that Bernard was examining closely. All the amounts of the ingredients were in decimals and grams. There were three recipes for the same coffee cake with only slight differences in the amounts of the ingredients. Next to each ingredient was its cost: 2¢, 5¢, etc. These were the most scientific cooks Sheryl had ever seen. They made their cooking an experimental activity rather than a job or an art.

“What’s that good aroma coming from the kitchen?” Sheryl asked.

“Our number 3 coffee cake. We’ll let you sample it when it’s done,” Bernard offered.

Dave kept rocking and reading. Bernard told him whether a recipe sounded good.

“Hey, you really like to cook, don’t you?” Sheryl said.

“Got to do something,” Bernard quickly replied.

This was their first cooking year. They often discussed recipes and cooking. They didn’t fit the stereotypes of young men or scientists. They shared a common interest with their mothers and grandmothers.

While everyone ate the coffee cake, Bernard fingered through Peterson’s bird guide. The researchers picked up field guides and keys to identifying all sorts of natural things—they thumbed through them the way most people look through a magazine or read a novel.

Karen, Sheryl’s sister, joined the group. “Let’s play the ‘What Bird Is It?’ game,” she said between munches of cake. “Like, what bird is a Halloween bird that plays dodge ball?” Karen invented a new game for the group.

“We give up,” Sheryl said.

“A masked duck,” Karen answered.

“Oh no—,” Dave moaned.

Dave M., a biology student, popped in for a break from the porch lab and got the drift of the game. “What about a party in a pasture bird?”

Quickly bird names flitted through their heads. Robin, bluebird, crow—nothing seemed to fit that description.

“Meadowlark,” Karen answered.

“Right!” Dave congratulated her.

Glancing up from his book, Bernard offered, “A large clear-stream bird.”

“Shearwater,” Karen responded, much to Bernard’s surprise.

“Almost. The greater shearwater,” he corrected her.

“The kitten bird,” Dot called from her caterpillar table.

That was easy. They all called at once, “The catbird.”

Television and radio reception were very poor. The Internet had not been invented yet, and there was no such thing as a cellular phone. Tape recorders and records brought classical music and the current rock sounds to the farmhouse. Piano music floated from the living room windows on warm evenings. Fiddlers and guitarists filled the house or the porch with lively country music.

Jokes focused on things that wouldn’t hurt people’s feelings. One man was teased about his “cold blood,” since he was always cold and needed his heavy jacket. Dave’s weekly casserole was inspected nightly for the new ingredient added each day. They all got along remarkably well, just like a family whose members liked and respected each other. Something usually was happening—it was never dull.

Sunny days brought timeless hours. The world seemed to be this one place. Time stood still. In free moments people sunned, hiked, picked berried, hunted antique bottles, watched birds and dogs.

Many pets came and went. Aob, a boa constrictor, had no snake-sitter at home. She had had to come along. Her cage was kept in the garage, and Frank, an ornithologist, moused for her.

The animal behaviorists discovered that a male and a female dog got along better than did two females or two males. When a new dog arrived, the first question was always, “Male or female?”

Donda, Frank’s boxer dog, gave lessons in territorial claims and defense. Whenever a new dog arrived on the scene, she had to get acquainted. The dogs learned either to play together or to stay in their own territory, which they defended with growls, barks, and threatening positions.

The older dogs put up with the capers of puppies. They taught them the rules of being a canine. Rick’s little red setter learned quickly to give up when attacked by a big dog. He rolled on his back and bared his throat to his attacker. He also learned to hide in small holes in the bushes and under cars.

A retriever played an outstanding game of Frisbee. She ran to catch the flying disk, caught it in her teeth, and returned it to her master. Time and time again she entertained the audience on the porch with her catching prowess.

Baseball, catch, badminton, and volleyball were the before- and after-dinner sports.

The first volleyball net was too low. People recoiled from the attacks of strong players. So Bernard made tall poles from two saplings and sunk them securely in the ground. An official-sized net was stretched between the poles, and boundary lines were roped off. Much better games followed.

As varied and different as the group was in appearance, personality, likes, and dislikes, they all seemed to really like the outdoors. On a weekend many would climb a mountain. Some tried to climb them all in one summer.

As a group, the researchers, like young people everywhere, had a wide range of individual interests and varied talents. Most important, they exercised their talents and interests, always actively involved in doing something. No one moped around, or wondered what to do. They were healthy, strong, and energetic.

Tom Baker, the insect expert, kept his legs and lungs fit for cross-country racing by running two to five miles a day. A few nights a week he played the piano in a local restaurant.

A Yale botany student named Tink swam around the lake regularly. He read Stalking the Wild Asparagus and did his own hunting and preparation of edible roots, seeds, and plants from the field. He also played in the Naval Reserve Band. His flute-playing inspired Karen to choose that instrument to play in school.

After the day’s bird-watching chores, Ian played the piano or fiddled for a hoedown with Tom S., a fellow Dartmouth student. Sometimes he sketched the animals and plants around him or pictured the funny doings of researchers.

Even though the researchers were strongly individual in their pursuit of interests and had their own ideas about lots of things, each was content to let the other person do her own thing if it didn’t interfere with his own activities.

Only an occasional helper had a reputation for crawling off into the grass, lost from view and a job assignment. If helpers didn’t like to work hard, they quit or didn’t come back. To most of them, the work was what they would choose to do, anyway. So the hours spent working were hours living, not waiting to live.

A more likable group of young people would be hard to find. The future rested in capable hands. All in their own ways became aware of earth’s population and environment problems. Each wanted to help. They were preparing themselves to help recognize and solve environmental problems. They were ready to make sacrifices. Several couples gave up their desire for many children and planned for one or two. Others planned all or partly adopted families. Still others decided to have no children of their own. They would give their time to other people’s children and devote their energies toward making the earth a better home for all the earth’s family members.

Projects grew. The number of people grew too. Pleasant View had its own population crunch. Something had to give. Another house was rented. It was christened PIP (Principal Investigator’s Pad) by the research assistants. Then the birders migrated to a “birdhouse” down the road.

Increasing numbers of researchers, assistants, and visiting scientists created new problems. The crowding was relieved by new rules, a new well, tents, a trailer, and more house rentals. And, in 2004, the Hubbard Brook Research Foundation was able to purchase 19 acres and additional housing units on Mirror Lake with the help of a group of supportive organizations. This helped protect Mirror Lake from real estate development while also providing living space for researchers.