Chapter 4 Essay Writing

What is an essay?

On a basic level, an essay is a piece of writing which consists of several paragraphs, rather than just one paragraph, and which attempts to explore or argue one or more points on a specific topic. An essay typically consists of an introduction with a thesis, body paragraphs which attempt to help develop and demonstrate your thesis, and end with a conclusion.

On a basic level, an essay is a piece of writing which consists of several paragraphs, rather than just one paragraph, and which attempts to explore or argue one or more points on a specific topic. An essay typically consists of an introduction with a thesis, body paragraphs which attempt to help develop and demonstrate your thesis, and end with a conclusion. Writing a college-level essay isn’t about getting the “right answer” or simply adhering to basic rules or conventions; it’s about joining a larger conversation with something original and important to say. It’s about trying to make sense of a complex question or problem and trying to contribute to our understanding of it in a meaningful way. At its core, an essay is about using writing to think together in ways that others can understand and engage with. You and your reader meet in the introduction, you go out together and have an adventure in the body paragraphs, and then you come back and reflect on what it meant in the conclusion.

Going beyond the 5-paragraph structure

You may have learned about the five-paragraph essay in school before, and you might be comfortable with it, too. That’s great! But while some of the five-paragraph format will be helpful for you in college, now, it’s time to expand on this to create essays of more than five paragraphs. Some essays, like essay questions in a history exam, might only require two paragraphs, while a research paper might require twenty paragraphs.

While there are various types of essays, as a whole, most college essays share general features and have similar goals. In this chapter, we will focus on what it means to write academic essays at the college level, breaking down each section into manageable parts.

Elements of an Essay

The Title

Titles are usually the first thing a reader will see when reading your essay. They state the topic, a direction for the topic, and should be specific, clear, and engaging. The quickest path to this is composing a title that states your exact subject. If you can also hint at your thesis in the title, it becomes much more effective.

Examples

- Understanding the Extinction of Bees

- How Fantasy Literature Makes Us All Better Thinkers

- How Elden Ring Proves Video Games Are Art

- Why We All Need to Spend Less Time on Our Phones

- What My Abuelita’s Pozole Taught Me About Family

Academic titles will often combine a catchy hook with a straightforward description of your specific focus using a colon.

Examples

- A Farewell to Flowers: Examining the Extinction of Bees

- Beyond Borders: A Personal History of ICE

- More Than Just a Livable Wage: Why We Need Universal Basic Income

- Bringing People Together: What Delicious in Dungeon Teaches Us About the Importance of Food

Thinking about who you want your audience to be is especially important to consider when crafting titles, since the quality of a title will often determine if someone reads your piece or not. Think of it as a brief appetizer to wet your reader’s appetite. Crafting titles also requires a good deal of creativity and fun. Ask yourself: if I saw someone’s essay titled this, would I want to read it?

Example

Example title for our sample essay:

“Not Kobe, Not Lebron, but both: Rethinking the NBA GOAT Debate”

Thesis Statements

Some thesis statements are a single sentence. Some are a few sentences long. It all depends on the scale of your argument (how much you are trying to prove or explore), and your audience.

Generally, a strong thesis statement must have the following qualities:

- It must be arguable: A thesis statement must state a point of view or judgment about a topic. An established fact is not considered arguable.

- It must be supportable: The thesis statement must contain a point of view that can be supported with evidence (reasons, facts, examples).

- It must be specific: A thesis statement must be precise enough to allow for a coherent argument within the span of a single essay and remain focused on the topic. The key to this is having a specific enough topic (e.g. focusing on a specific horror book for a four-page essay – like Dracula – rather than the entire history of horror fiction). Thesis statements which are too broad are often unconvincing and become unwieldy for you as a writer.

Examples

Examples of Strong Thesis Statements

- Drug-awareness campaigns targeted at children are less successful at preventing substance abuse than campaigns targeting poverty as a whole.

- A regular exercise regime leads to multiple benefits, both physical and emotional. This is especially the case with cardio-based activities.

- The NBA’s product today is much worse than in previous generations due to the overemphasis of corporate revenue and three-point shooting among basketball teams.

- The first two years of community college education (and the costs associated with it) should be free to everyone. Doing so will have far reaching effects, including lower poverty rates across various communities.

Examples of Weak Thesis Statements

1. My paper will explain why imagination is more important than knowledge.

This is a weak thesis statement because it only announces the topic and content of the essay; it doesn’t make a specific, arguable claim about exactly why imagination is more important than knowledge. It’s also super broad – “imagination” and “knowledge” are massive topics, and as such, will most likely be unsupportable in the space of a college paper.

2. Advertising companies use sex to sell their products.

This is a weak thesis statement because it only contains an obvious fact (something that no one can reasonably disagree with) which sets the paper up to be a road to a dead end.

3. Laws need to be enacted to reduce pollution.

This is a weak thesis statement because it is too broad. Which laws, what types of pollution? Who would/should enact the laws? Without these specifics, the thesis statement becomes unsupportable.

4. The issue of texting and driving.

This is a weak thesis statement because it is incomplete; it is a sentence fragment. It gives a topic, but it does not include a verb or opinion about that topic.

5. “Growing up with three sisters has taught me to share my hair dryer.

This is a very specific example that is too narrow as it doesn’t allow for a broad discussion of sharing or the broader lessons of growing up with siblings.

6. Humanity has always hated each other.

This is a weak thesis statement because like the one above, it is also too broad and cannot be proven within the space of a college class essay.

7. Drugs are harmful and should be stopped.

This is a weak thesis statement because it also contains an obvious fact (drugs are bad). It’s also not specific (Which drugs? What harm?).

Exercise 4.1

Rewrite each weak thesis statement above to make it strong.

Introductions

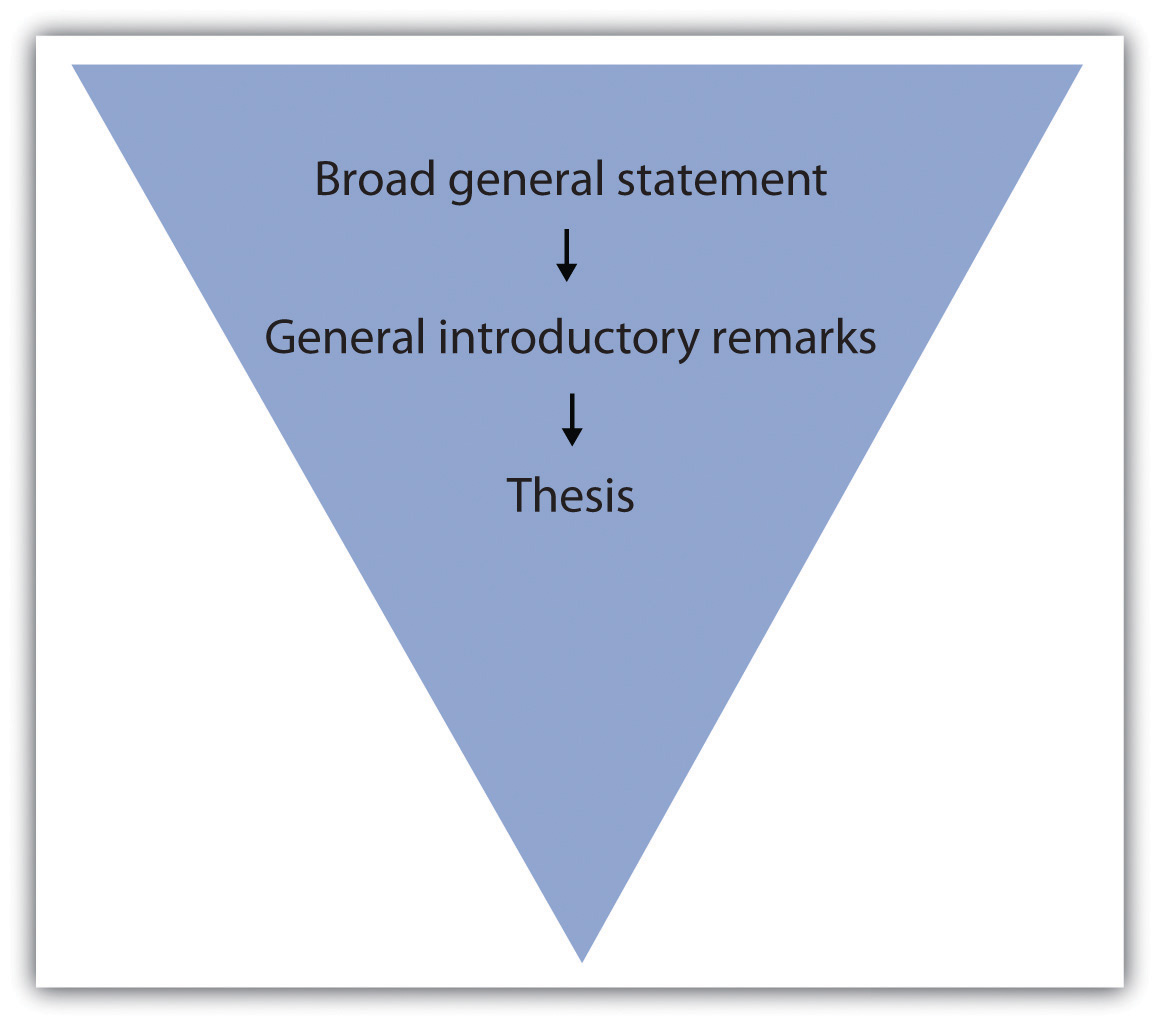

There are several approaches to writing an introduction, each of which fulfills the same goals. Like a good title, a good introduction captures a reader’s attention and makes them want to read on, but it should also provide background information and present the writer’s topic and thesis. Additionally, it helps give a sense of the direction of ideas in the essay, so readers know what to expect.

There are several approaches to writing an introduction, each of which fulfills the same goals. Like a good title, a good introduction captures a reader’s attention and makes them want to read on, but it should also provide background information and present the writer’s topic and thesis. Additionally, it helps give a sense of the direction of ideas in the essay, so readers know what to expect. Hook the Audience

To grab a reader’s attention, many writers like to begin with one (or more) of the following openers or “hooks.” To demonstrate how each hook might look, we took one paragraph and just changed the hook in each example below.

A surprising or interesting fact related to your topic

Share an interesting, shocking, or little known fact or statistic about your topic. Starting your paper with a fact or statistic that gives your readers insight into your topic right away will peak their curiosity and make them want to know more. It will also help you establish credibility from the very beginning.

Example

A thought-provoking question

Ask a question that gets readers curious about the answer. People tend to want to answer questions when they’re presented with them. This provides you with an easy way to catch readers’ attention because they’ll keep reading to discover the answer to any questions you pose in the introduction. Just be sure to answer them at some point in your writing.

Example

An attention-getting quote

This attention-getting device uses the words of another person that relate directly to your topic. If the person you are quoting is not well known, it is a good idea to provide information of why that person is relevant in the context of your essay.

Example

A brief anecdote related to your topic

Tell an anecdote or story that will help readers connect with your topic on a personal level. Sharing a human interest story right away will help readers connect with your topic on a personal level and will help to illustrate way your topic matters.

Example

A connection between your topic and your readers’ experiences

Provide an example of how the essay’s topic could have been experienced by the reader.

Example

Set Expectations

Example

Example introduction and thesis for our sample essay:

If there’s one thing NBA fans love to do, it’s debating the greatest player of all time: who deserves the mantle of the undisputed GOAT. And not just fans but NBA media and even NBA players themselves. For some, it’s Michael Jordan. For others, Kobe Bryant. For lots of people today, it’s Lebron James. When it comes to this debate, I don’t have an opinion on who the actual GOAT is. Instead, I want to try and demonstrate why this very debate itself is harmful for overall appreciation of the game. In other words, I think trying to pinpoint the GOAT is not only impossible, but it also keeps us from admiring the unique attributes of individual players.

Body Paragraphs

The term body paragraph refers to any paragraph that appears between the introductory and concluding sections of an essay. A good body paragraph should support your thesis statement by developing only one key supporting or relevant idea. You should have as many body paragraphs as are necessary to properly demonstrate or work through your thesis. d

Body paragraphs typically include:

- A topic sentence that declares the focus of the paragraph.

- The body (here’s where you include supporting statements / evidence).

- A conclusion which summarizes your overall point of the paragraph or which helps your reader prepare for the next paragraph to come.

For more information on how to structure a body paragraph, see the Chapter 3: Paragraph Structure.

Example

Below are two body paragraphs to follow the introduction example above.

Before we think about how to go beyond the GOAT debate, we should think about: why do people want to prove who the GOAT is in the first place? For Oliver Mayer, a professor at USC, it’s because sports figures are our modern-day gods, like those found in ancient Greek mythology. By arguing with each other who the undisputed GOAT is, we’re able to turn single, individual stories into eternal legends that last forever: “By refusing to admit loss, you never really grow up. Time never passes. You are the greatest now, and forever . . . Greatness is momentary, even for the G.O.A.T.s of the world. And the fact that greatness is momentary is precisely why it should be appreciated in all its forms” (Mayer). In this view, the GOAT debate is about turning players into gods that we can then worship for all time (like how back in ancient Greece everyone had a specific god they loved to worship).

I don’t think this is the only reason the GOAT debate is so infectious. however. Yes, it can be about a human need for identifying with gods, and the competition that comes from that. But honestly, I think it’s even simpler than that. I think it’s easier to argue who is the individual GOAT than try and understand greatness in all its forms across many players. In other words, understanding something different than what you’re used to. People typically don’t like difference. It takes time, it takes consideration to understand someone else’s view; it also takes humility. If a person grows up watching Lebron James and not Kobe, or vice versa, then trying to figure out what the other player does great takes work, as well as the willingness to be wrong. Focusing on what your personal GOAT did as a player is a lot less work than going back and watching another candidate’s highlights and then appreciating their game in a way that you’re not used to.

Work Cited

Mayer, Oliver. “Why We Love the Great G.O.A.T. Debate.” Zocalo Public Square, Arizona Board of Regents, 22 June 2023, https://www.zocalopublicsquare.org/why-we-love-the-goat-debate/

Conclusions

Below are some things to consider when writing your conclusion:

- What is the significance of the ideas you developed in this paper?

- How does your paper affect or relate to you, others like you, people in your community, or people in other communities?

- What must be done about this topic?

- What further research or ideas could be studied?

- What are some things you weren’t able to consider in your essay? What might be the limitations of your ideas?

Many writers like to end their essays with a final emphatic statement. This strong closing statement will cause your readers to continue thinking about the implications of your essay; it will make your conclusion, and thus your essay, more memorable. Another powerful technique is to challenge your readers to make a change in either their thoughts or their actions. Challenging your readers to see the subject through new eyes is a powerful way to ease yourself and your readers out of the essay.

And yet, as you work through your conclusion, note that this is also the best place for humility. Be honest in admitting short-comings in your ideas, explanations, or comprehensiveness. Humility in the conclusion shows a writer who is honest and thoughtful. This is not to be confused with contradiction, false humility, self-deprecation, or un-rebutted opposition. Instead, the humility of honesty is the aim here.

Example

Completed Essay with Conclusion

“Not Kobe, Not Lebron, but both: Rethinking the NBA GOAT Debate”

If there’s one thing NBA fans love to do, it’s debating the greatest player of all time: who deserves the mantle of the undisputed GOAT. And not just fans but NBA media and even NBA players themselves. For some, it’s Michael Jordan. For others, Kobe Bryant. For lots of people today, it’s Lebron James. When it comes to this debate, I don’t have an opinion on who the actual GOAT is. Instead, I want to try and demonstrate why this very debate itself is harmful for overall appreciation of the game. In other words, I think trying to pinpoint the GOAT is not only impossible, but it also keeps us from admiring the unique attributes of individual players.

Before we think about how to go beyond the GOAT debate, we should think about: why do people want to prove who the GOAT is in the first place? For Oliver Mayer, a professor at USC, it’s because sports figures are our modern-day gods, like those found in ancient Greek mythology. By arguing with each other who the undisputed GOAT is, we’re able to turn single, individual stories into eternal legends that last forever: “By refusing to admit loss, you never really grow up. Time never passes. You are the greatest now, and forever . . . Greatness is momentary, even for the G.O.A.T.s of the world. And the fact that greatness is momentary is precisely why it should be appreciated in all its forms” (Mayer). In this view, the GOAT debate is about turning players into gods that we can then worship for all time (like how back in ancient Greece everyone had a specific god they loved to worship).

I don’t think this is the only reason the GOAT debate is so infectious. however. Yes, it can be about a human need for identifying with gods, and the competition that comes from that. But honestly, I think it’s even simpler than that. I think it’s easier to argue who is the individual GOAT than try and understand greatness in all its forms across many players. In other words, understanding something different than what you’re used to. People typically don’t like difference. It takes time, it takes consideration to understand someone else’s view; it also takes humility. If a person grows up watching Lebron James and not Kobe, or vice versa, then trying to figure out what the other player does great takes work, as well as the willingness to be wrong. Focusing on what your personal GOAT did as a player is a lot less work than going back and watching another candidate’s highlights and then appreciating their game in a way that you’re not used to.

As I hope this essay has conveyed, basketball GOAT debates are pointless and take us away from truly appreciating the individual talents of all players across various generations. I’d love to see NBA fans talk less about LeBron vs. MJ and more about the mind-blowing physics of Curry’s three-pointers or the exciting differences between a Magic pass and a Luka pass. And as true as I think this is for NBA fans, I think this is an important lesson potentially for fans of any game. I think about how growing up I thought PlayStation was the best kind of console and because of that, it kept me from playing a bunch of amazing Xbox or Nintendo games. I couldn’t see how Bloodborne AND Halo were masterpieces in their own unique ways. I think we’d all be better off abandoning the lens of “the greatest” and instead embrace the question: “how is this specific thing great in its own way?” While sports are competitions, appreciating the game doesn’t (and shouldn’t) have to be.

Work Cited

Mayer, Oliver. “Why We Love the Great G.O.A.T. Debate.” Zocalo Public Square, Arizona Board of Regents, 22 June 2023, https://www.zocalopublicsquare.org/why-we-love-the-goat-debate/

Organizing Your Essay

Even though you might have an overall structure for your essay and all your main ideas planned, the best order for those ideas and their body paragraphs may not be apparent. But how you arrange your essay is just as important as what you say in your essay. The way you structure your essay helps your readers draw connections between the body and the thesis, and the structure also keeps you focused as you plan and write the essay.

For example, when first starting your essay, your ideas may seem to flow from your mind in a seemingly random manner, without a clear or logical ordering. Your readers, who bring to the table different backgrounds, viewpoints, and ideas, need you to clearly organize these ideas in order to understand what you’re trying to say.

This section covers three ways to organize body paragraphs:

- Chronological order

- Order of importance

- Spatial order

Chronological Order

Chronological Order

Chronological arrangement has the following purposes:

- To explain the history of an event or a topic

- To tell a story or relate an experience

- To explain how to do or to make something

- To explain the steps in a process

Chronological order is mostly used in expository writing, which is a form of writing that narrates, describes, or explains a process. When using chronological order, arrange the events in the order that they actually happened, or will happen if you are giving instructions. This method requires you to use words such as first, second, then, after that, later, and finally. These transition words guide you and your reader through the paper as you expand your thesis.

For example, if you are writing an essay about the history of a specific baseball team, you would begin with when the team was first established, and then detail the essential timeline events up until present day. You would follow the chain of events using words such as first, then, next, and so on.

Keep in mind that chronological order is most appropriate for the following purposes:

- Writing essays containing heavy research

- Writing exploratory essays with the aim of listing, explaining, or narrating

- Writing essays that describe literary works such as poems, plays, or books

When using chronological order, your introduction should indicate the information you will cover and in what order, and the introduction should also establish the relevance of the information. Your body paragraphs should then provide clear divisions or steps in chronology. You can divide your paragraphs by time (such as decades or important standout events) or by the same structure of the work you are examining (such as chapters in a book or episodes of a TV show).

Order of Importance

- Persuading and convincing

- Ranking items by their importance, benefit, or significance

- Illustrating a situation, problem, or solution

Many essays move from the least to the most important point, and the paragraphs are arranged in an effort to build the essay’s strength. Sometimes, however, it is necessary to begin with your most important supporting point, such as in an essay that contains a thesis that is highly debatable. When writing a persuasive essay, it is best to begin with the most important point because it immediately captivates your readers and compels them to continue reading. For example, if you were supporting your thesis that homework is detrimental to the education of high school students and should be eliminated, you would potentially want to present your most convincing argument first, and then move on to the less important points for your case.

Some key transitional words you should use with this method of organization are most importantly, almost as importantly, just as importantly, and finally.

Spatial Order

- Helping readers visualize something as you want them to see it

- Evoking a scene using the senses (sight, touch, taste, smell, and sound)

- Writing a descriptive essay

Spatial order means that you explain or describe objects as they are arranged around you in your space, for example in a bedroom. As the writer, you create a picture for your reader, and their perspective is the viewpoint from which you describe what is around you.

The view must move in an orderly, logical progression, giving the reader clear directional signals to follow from place to place. The key to using this method is to choose a specific starting point and then guide the reader to follow your eye as it moves in an orderly trajectory from your starting point.

Pay attention to the following student’s description of her bedroom and how she guides the reader through the viewing process, foot by foot.

Attached to my bedroom wall is a small wooden rack dangling with red and turquoise necklaces that shimmer as you enter. Just to the right of the rack is my window, framed by billowy white curtains. The peace of such an image is a stark contrast to my desk, which sits to the right of the window, layered in textbooks, crumpled papers, coffee cups, and an overflowing ashtray. Turning my head to the right, I see a set of two bare windows that frame the trees outside the glass like a 3-D painting. Below the windows is an oak chest from which blankets and scarves are protruding. Against the wall opposite the billowy curtains is an antique dresser, on top of which sits a jewelry box and a few picture frames. A tall mirror attached to the dresser takes up most of the wall, which is the color of lavender.

The paragraph incorporates two objectives you have learned in this chapter: using an implied topic sentence and applying spatial order. Often in a descriptive essay, the two work together.

The following are possible transition words to include when using spatial order:

- Just to the left or just to the right

- Behind

- Between

- On the left or on the right

- Across from

- A little further down

- To the south, to the east, and so on

- A few yards away

- Turning left or turning right

Outlining

Once you have chosen an order for your essay’s information, you can now map out your plan using an outline. Creating an outline might seem like an unnecessary step. However, outlines ensure that your argument is well-organized and stays on topic. In addition, a well-thought out outline can save hours of writing time. After all, it’s much easier to re-organize an outline than to re-write an entire essay!

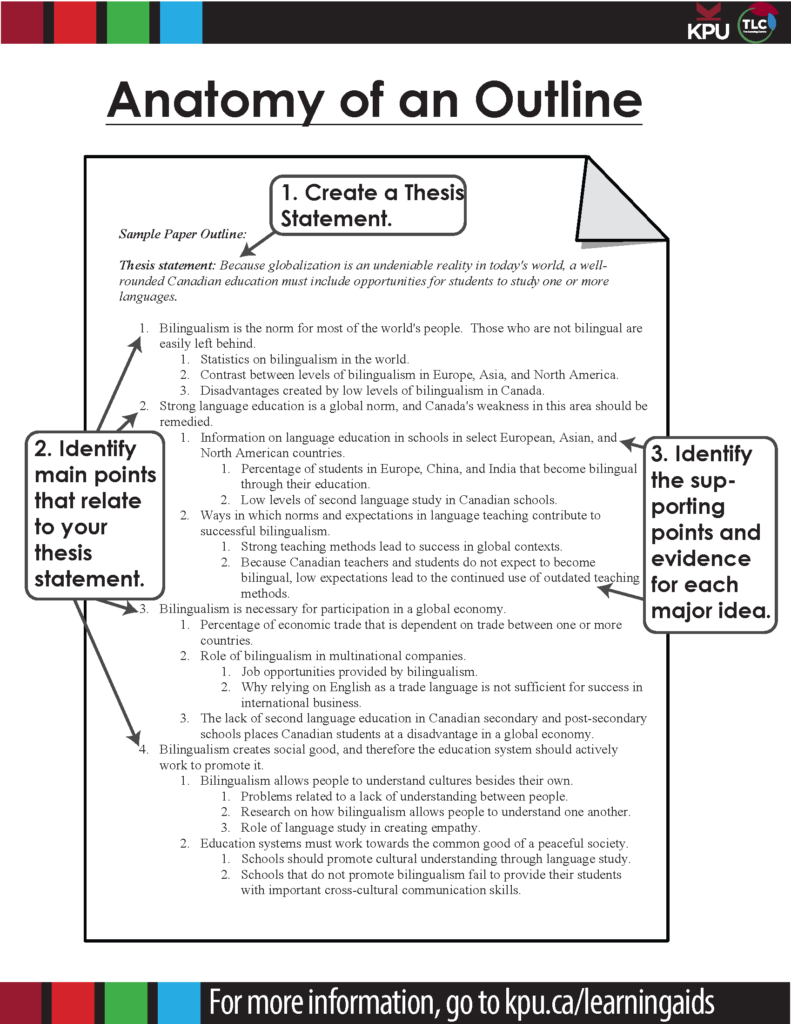

Below are steps to creating an outline.

Step 1: Create a thesis statement

You will begin by writing a draft thesis statement. As stated above, your thesis statement is the core, unifying argument of your essay. Write the thesis statement at the top of your paper. You can revise this later if needed.

The rest of your outline will include the main point and sub-points you will develop in each paragraph.

Step 2: Identify the main ideas that relate to your thesis statement

List the main points that you plan to discuss in your essay. Consider carefully the most logical order, as discussed above, and how each point supports your thesis. These main ideas will become the topic sentences for each body paragraph.

Step 3: Identify the supporting points and evidence for each major idea

Each main point will be supported by supporting points and evidence that you have compiled from other sources. Each piece of information from another source must be cited, whether you have quoted directly, paraphrased, or summarized the information.

Step 4: Create your outline

Outlines are usually created using a structure that clearly indicates main ideas and supporting points. In the example below, main ideas are numbered, while the supporting ideas are indented one level and labelled with letters. Each level of supporting detail is indented further.

Essay Planning and Writing

Now that you’ve learned what goes into a typical college essay, here are some exercises to help you better practice planning and writing your own essays.

Exercise 4.2

Once you have a topic that you’d like to write an essay on, try and plan out how you think you’d organize your essay. Remember this is just a draft – once you begin writing your essay, change is not only expected, but probably a good thing! Feel free to be as messy as you need to be.

Key Takeaways

- An essay is a cohesive written work that consists of several paragraphs and is organized around a specific topic.

- Proper college essays require a thesis statement to provide a specific focus and suggest how the essay will be organized.

- A thesis statement is your interpretation of the subject, not the topic itself.

- A strong thesis is specific, precise, forceful, confident, and is able to be demonstrated.

- A strong thesis challenges readers with a point of view that can be debated and can be supported with evidence.

- A weak thesis is simply a declaration of your topic or contains an obvious fact that cannot be argued.

- A weak thesis is too broad or too general to work in the space of a single essay.

- An essay includes an introduction paragraph that ends with a thesis statement; supporting body paragraphs; and a conclusion paragraph.

- An essay should be organized in a logical manner using spatial order, chronological order, or order of importance.

- Outlines can help you organize your ideas.

Attributions

Crafting Coherent Essays: An Academic Writer’s Handbook by Erik Wilbur is licensed under CC BY 4.0

The Writing Textbook by Josh Woods, editor and contributor, as well as an unnamed author (by request from the original publisher), and other authors named separately is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Advanced English by Allison Kilgannon is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0

You, Writing! by Kelli Hallsten-Erickson and Amy Jo Swing Is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

4.7: Writing Your Draft was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Kathryn Crowther, Lauren Curtright, Nancy Gilbert, Barbara Hall, Tracienne Ravita, and Kirk Swenson (GALILEO Open Learning Materials) and is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

1.5: Ordering Evidence, Building an Argument by Salvatore F. Allosso and Dan Allosso is shared under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license

4.1: Basic Essay Structure was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Angela Spires, Brendan Shapiro, Geoffrey Kenmuir, Kimberly Kohl, and Linda Gannon and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

The RoughWriter’s Guide Copyright © 2020 by Dr. Karen Palmer and Dr. Sandi Van Lieu is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License,

University 101: Study, Strategize and Succeed Copyright © 2018 by Kwantlen Polytechnic University is licensed under a CC BY-SA 4.0

Types of Introductions. by Anne Fleischer with Lumen Learning is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Media Attributions

- person holding on red pen while writing on book © lilartsy

- Formula for a Thesis © Shelley Decker is licensed under a Public Domain license

- People shaking hands © Resume Genius

- Funnel Image © Josh Woods is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Cuckoo Clock © Erik Mclean

- 1, 3, and 5 Star Ratings © nerdy is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Photo of an Interior © deborah cortelazzi

- Anatomy of an Outline © Graeme Robinson-Clogg adapted by Kwantlen Polytechnic University is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license