Chapter 6 Research Methods

Research Methods

Most students hear the word research, and they cringe. They envision a long, drawn-out process with limited success, and, horror of horrors, documentation. This chapter is devoted to alleviating student anxiety and facilitating the research process. In fact, the unit is broken down into steps, so just follow them one by one.

Step 1: What is Your Topic?

If the research project is open-ended, use the strategies outlined in Chapter 2: The Writing Process to figure out what your topic will be.

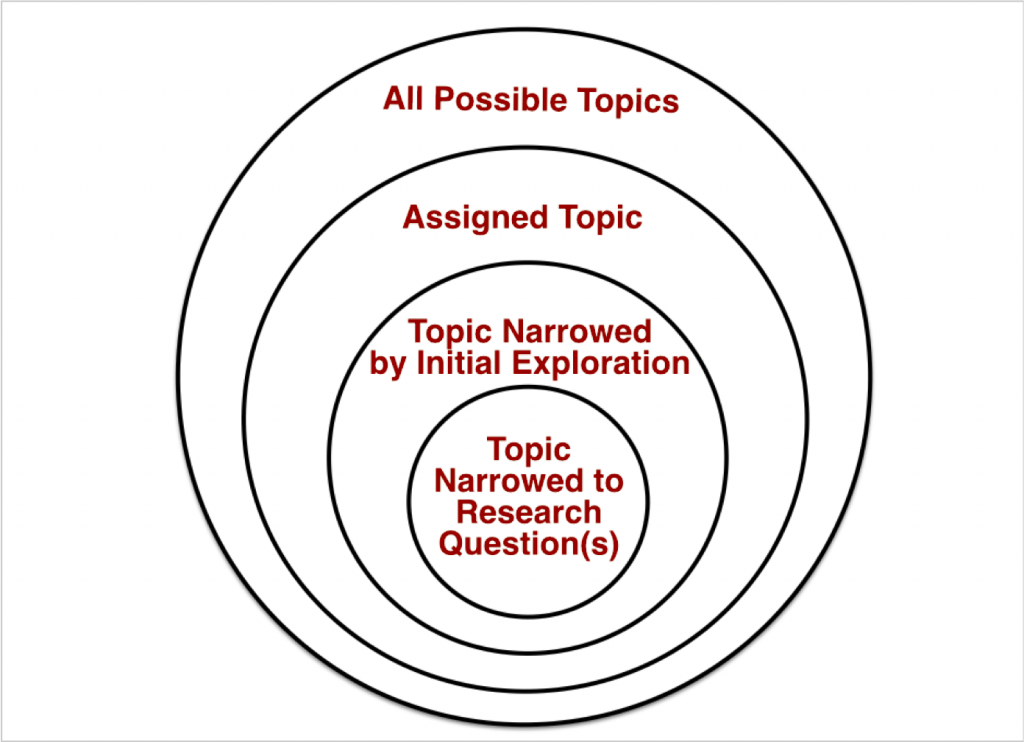

Narrowing Your Topic

- How many different aspects of this topic am I able to list? You may want to consult Google or the CAC Library databases, such as Issues & Controversies, Opposing Viewpoints or Newsbank to get you started here if you are stuck. Write down the list.

- Of those aspects listed above, which am I most interested in learning more about? Write down one or two and follow steps 3 and 4 for each one. You may find that you come up with more than one interesting research question. Then you’ll need to choose!

- Of the aspect that most interests me, what elements of it am I able to find information about in CAC Library databases such as Issues & Controversies, Opposing Viewpoints, or Newsbank? (Notice that you may need to repeat this step more than once to really get down to a workable limited focus.) Make a list.

- What relationships between these elements are suggested by combining them using what, when, where, why, or how words?

All writing is created for a specific audience. Writers must identify the specific reader they want to reach. Your audience is the person or group whom you intend to reach with your writing. You might ask this question: isn’t my instructor always my audience? Sometimes your instructor will be your intended audience, and your purpose will be to demonstrate your learning about a particular topic to earn credit for an assignment. Other times, even in your college classes, your intended audience or readers will be a person or group outside of the instructor or your peers. This could be someone who has a personal interest in or need to read about your topic but who may never actually read your work unless it finds a place to be published like a blog or website. Understanding who your intended audience is and who your readers might be will help you shape your writing.

- What do I know about my audience and my readers? (age, gender, interests, biases, or concerns; Do they have an opinion already? Do they have a stake in the topic?)

- What do they know about my topic? (What does this audience or my readers not know about the topic? What do they need to know?)

- What details might affect the way this audience or my readers thinks about my topic? (How will facts, statistics, personal stories, examples, definitions, or other types of evidence affect these audience/readers? What kind of effect are you going for?)

- If they are writing for a general audience, what is the best way to capture a wide range of readers’ interests?

- Should they provide background information that general readers would not necessarily know?

- Are they writing for an audience already well versed in this topic, and, if so, does this mean writers can use more scholarly language and include less background information?

Step 3: What Types/Kinds of Research Are Required?

After nailing down a research topic, decide whether to use primary or secondary sources. When it comes to secondary, instructors may want a combination of popular and scholarly. And, lastly, sometimes, your instructor will push you to consider both primary and secondary that come from both popular and scholarly areas.

Primary vs. Secondary Sources

Secondary sources are the gathering of information that has previously been analyzed, assessed, or otherwise documented or compiled including: sources (print or electronic) such as books, academic journals, magazine articles, Wikipedia, reports, documentaries, correspondence, etc.

|

Discipline |

Example Fields |

Primary Source Examples |

Secondary Source Examples |

|

Arts |

Visual Arts, Performing Arts |

Sketchbooks, scripts, plays, sculptures, music |

Critical reviews in journal articles, publications about the authors/artists and their works |

|

Humanities |

Philosophy, History, Literature, Languages |

Speeches, diaries, narratives, artifacts, interviews, short stories, original research |

Reviews of books, literary criticisms, topical monographs, journal articles, annotated bibliographies, documentaries |

|

Social Sciences |

Business, Psychology, Political Science, Education, Economics |

Studies, lesson plans, case reports, surveys, market research and testing, statistical data, published results of clinical trials |

Publications about the significance of research or experiments, reviews of results |

|

Natural Sciences and Applied Sciences |

Biology, Chemistry, Physics, Mathematics, Engineering, Medicine, Agriculture, Computer Science |

Published results of experiments, observations, discoveries, technical reports, models, schematic drawings, specimens, designs |

Publications about the significance of research or experiments, reviews of results |

Popular, Scholarly, or Trade Sources

- Popular magazine articles are typically written by journalists to entertain or inform a general audience,

- Scholarly articles are written by researchers or experts in a particular field. They use specialized vocabulary, have extensive citations, and are often peer-reviewed.

- Trade publications may be written by experts in a certain industry, but they are not considered scholarly, as they share general news, trends, and opinions, rather than advanced research, and are not peer-reviewed.

|

|

Popular Magazines |

Scholarly (including peer-reviewed) |

Trade Publications |

|

Content |

Current events; general interest articles |

Research results/reports; reviews of research (review articles); book reviews |

Articles about a certain business or industry |

|

Purpose |

To inform, entertain, or elicit an emotional response |

To share research or scholarship with the academic community |

To inform about business or industry news, trends, or products |

|

Author |

Staff writers, journalists, freelancers |

Scholars/researchers |

Staff writers, business/industry professionals |

|

Audience |

General public |

Scholars, researchers, students |

Business/industry professionals |

|

Review |

Staff editor |

Editorial board made up of other scholars and researchers. Some articles are peer-reviewed |

Staff editor |

|

Citations |

May not have citations, or may be informal (ex. according to… or links) |

Bibliographies, references, endnotes, footnotes |

Few, may or may not have any |

|

Frequency |

Weekly/monthly |

Quarterly or semi-annually |

Weekly/monthly |

|

Ads* |

Numerous ads for a variety of products |

Minimal, usually only for scholarly products like books |

Ads are for products geared toward specific industry |

|

Examples on Publisher Site |

Step 4: How Do I Find Quality Secondary Research?

Search Tricks

Accurate terms or punctuation changes should be used to signal a more specific search or topic and lead to better results. First, determine what words or phrase best suits your needs. For example: If you are looking for information through a Google search regarding a specific type of dieting, use quotation marks to indicate to the search engine that you are just looking for “vegan restaurants in California.” This will narrow down the return you get in your search. If you are using the CAC Library databases, type in a specific phrase related to your topic. For example: If you are looking for research in Issues & Controversies on how a vegan diet may benefit one’s health, type “vegan diet” into the search button; then click the “News” option under “Search Results.”

These Search Tricks (also called Boolean and/or Proximity Searching) allow you to specify how close a search term appears in relation to another term contained in the resources you find. Boolean search operators show relation to other terms using and, or not, etc. Similarly, Proximity operators are shorthand notations used during a search that usually has a number to indicate how close search terms should appear.

- Using “AND” retrieves articles that contain all the terms and narrows down the search.

-

- Example: “child abuse” AND Maryland

- Using “OR” retrieves articles with an of the terms and broadens the search.

-

- Example: obesity OR overweight children OR juveniles

- Using “NOT” eliminates articles containing the second term and narrows the search

-

- Example: depression AND teens NOT adults

-

- Example: “video games” AND teenagers NOT children

Database Searching

Becoming adept at searching online databases will give you the confidence and skills you need to gather the best sources for your project.

Your online college library can help you learn how to select search terms and understand which database would be the most appropriate for your project. College libraries will require login information from students to access database resources.

The instructions to access CAC’s library databases can be found here. To access CAC’s library databases: Go to Blackboard. Click “Organizations.” Then go to “Library Resources.” There, you will find a link to “Databases”, and you can search databases relevant to your issue. Databases such as Issues and Controversies, Opposing Viewpoints, and Academic OneFile are great for many assignments.

For an overview of CAC’s library services, check out this video:

Internet Searching

As a general rule, one site to avoid is Wikipedia, which is not considered a quality source for academic writing. While this site is fine for looking up information in a casual way and gaining a better understanding of a subject, it is not recommended for academic writing because information can sometimes be incorrect since the content is user-generated, rather than peer reviewed and written by experts (i.e., scholarly). Peer reviewed and works written by experts can be found in academic journals or published books. Wikipedia is also considered more of a “general knowledge” source, and academic writing favors sources with more specific information.

Still, when you are researching on the web, search engines are effective tools for locating web pages relevant to your research, and they can save you time and frustration. However, for searches to yield the best results, you need a strategy and some basic knowledge of how search engines work. Without a clear search strategy, using a search engine is like wandering aimlessly in a field of corn looking for the perfect ear.

Choosing the appropriate search engine for scholarly sources is simple—if one is assigned or you have already become well versed in online research. However, if you are a novice in the field of research, the following list of electronic search engines may ease some of your research stress.

- Google Scholar was created as a tool to congregate scholarly literature on the web. https://scholar.google.com/. See this website for tips on how to get the most out of Google!

- Populated by the U.S. Department of Education, the Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC) is a great tool for academic research with more than 1.3 million bibliographic records of articles and online materials.

Implement the C.R.A.A.P. Test

Need a good way to evaluate a source? Take a look at “C.R.A.A.P.”! The C.R.A.A.P. method is a way to determine the validity and relevance of a source. C.R.A.A.P. stands for

If the source you’re looking at is current, relevant, and accurate, it’s probably a good source to use. Depending on the aim of your paper, you’ll be looking for an authority and purpose that are unbiased and informative.

If the source you’re looking at is current, relevant, and accurate, it’s probably a good source to use. Depending on the aim of your paper, you’ll be looking for an authority and purpose that are unbiased and informative.

What questions should you ask about your source?

The C.R.A.A.P. test provides a guideline for identifying whether a source is trustworthy. The questions below help guide the review of sources for credibility, but a source does not have to answer positively on all questions to be a credible source. Use good judgement and the answers to the questions should guide a determination of the source’s quality.

C – Currency: The timeliness of the information:

- When was the information published or posted?

- Has the information been revised or updated?

- Does your topic require current information, or will older sources work as well?

- Are the links functional?

R – Relevance: The importance of the information for your needs:

- Does the information relate to your topic or answer your question?

- Who is the intended audience?

- Is the information at an appropriate level (i.e. not too elementary or advanced for your needs)?

- Have you looked at a variety of sources before determining this is one you will use?

- Would you be comfortable citing this source in your research paper?

A – Authority: The source of the information:

- Who is the author/publisher/source/sponsor?

- What are the author’s credentials or organizational affiliations?

- Is the author qualified to write on the topic?

- Is there contact information, such as a publisher or email address?

- Does the URL reveal anything about the author or source?

A – Accuracy: The reliability, truthfulness, and correctness of the content

- Where does the information come from?

- Is the information supported by evidence?

- Has the information been reviewed or refereed?

- Can you verify any of the information in another source or from personal knowledge?

- Does the language or tone seem unbiased and free of emotion?

- Are there spelling, grammar or typographical errors?

P – Purpose: The reason the information exists:

What is the purpose of the information? Is it to inform, teach, sell, entertain or persuade?

- Do the authors/sponsors make their intentions or purpose clear?

- Is the information fact, opinion or propaganda?

- Does the point of view appear objective and impartial?

- Are there political, ideological, cultural, religious, institutional or personal biases?

Step 6: “How do I know when to quote, paraphrase, or summarize?”

There is no easy answer, it just takes practice. You will work with a number of instructors who will have different ideas on what you should do. To start, here are a few general guidelines.

Quoting

Use the exact words of an author, copied directly from the source, word for word. You must use quotation marks and an in-text citation.

Use quotes when you want to

- add the power of the author’s words to support your argument or claims

- disagree with something specific an author said

- highlight a specific passage

- compare or contrast points of view

Paraphrasing

Paraphrasing is stating an idea, point or passage in your own words. You must significantly change the wording, phrasing, and sentence structure of the source (not just a few words here and there; don’t just use a thesaurus and change out terms!). Every paraphrase must also have in-text citations at the end of the paraphrased section and the original source identified on reference or works cited page.

Paraphrase when you want to

- clarify a short passage from a text

- avoid overusing quotations

- explain a point when exact wording isn’t critical

- articulate the main ideas of a passage or part

- report numerical data or statistics

Summarizing

Summaries are a broad overview of the entire original material (not just a part, like a paraphrase). You may summarize an entire article, and then also paraphrase a small portion of the author’s findings. Like quotes and paraphrases, a summary must be cited with in-text citations and on your works cited page.

Summarize when you want to

- give an overview of a topic

- describe information (from several sources) about a topic

Learning these skills takes practice. It is okay if you are feeling overwhelmed.

Example of Summarizing, Paraphrasing, and Quoting

Below is an excerpt from “Letter from Birmingham Jail” by Martin Luther King, Jr., and following are examples of a summary, a paraphrase, and a quote.

Exerpt from “Letter from Birmingham Jail” by Martin Luther King, Jr.

You may well ask: “Why direct action? Why sit-ins, marches and so forth? Isn’t negotiation a better path?” You are quite right in calling, for negotiation. Indeed, this is the very purpose of direct action. Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue. It seeks to so dramatize the issue that it can no longer be ignored. My citing the creation of tension as part of the work of the nonviolent resister may sound rather shocking. But I must confess that I am not afraid of the word “tension.” I have earnestly opposed violent tension, but there is a type of constructive, nonviolent tension which is necessary for growth. Just as Socrates felt that it was necessary to create a tension in the mind so that individuals could rise from the bondage of myths and half-truths to the unfettered realm of creative analysis and objective appraisal, we must see the need for nonviolent gadflies to create the kind of tension in society that will help men rise from the dark depths of prejudice and racism to the majestic heights of understanding and brotherhood.

Example Summary

King clarifies that there are two approaches to protest—violent and nonviolent—and although they both create pressure, violent resistance is destructive while nonviolent resistance is constructive.

Examples

Original:

You may well ask: “Why direct action? Why sit-ins, marches and so forth? Isn’t negotiation a better path?” You are quite right in calling, for negotiation. Indeed, this is the very purpose of direct action. Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue.

Paraphrase:

King understands that the reader may think protests are not needed and that negotiating would be more productive. He points out that the people in power have refused to negotiate and so the protests are designed to encourage those people to negotiate (King).

Examples

While King agrees that negotiation is necessary but states, “Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue” (King).

Important Reminder!

Whether summary, paraphrase, or quotation, you need to use an in-text citation! For every in-text citation, ensure there is a matching entry on the Works Cited page! Also, remember to use information from sources only to support your own argument. For a research essay, a healthy ratio is generally no more than 10% to 20% material from sources to 80% your own original ideas, argument, interpretation, analysis, and explanation. This is not a rule as much as a reminder to think critically about how much your writing relies on the ideas of others: unless the assignment is a summary or literature review, the emphasis should be on your ideas!

Step 7: How Do I Avoid Plagiarism?

- Understand what types of information must be cited

- Understand what constitutes fair use of a source

- Keep source materials and notes carefully organized

- Distinguish what information is composed of facts or general statements that are common knowledge

What is Common Knowledge?

Common knowledge is a fact or general statement that is commonly known. For example, a writer would not need to cite the statement that fruit juices contain sugar; this is well known and well-documented. However, if a writer explained the differences between the chemical structures of the glucose molecule and how sugar is related to today’s levels of obesity in America, a citation would be necessary. When in doubt, cite.

Value Your Own Voice

Plagiarism is the result of students who lack confidence in their ability to communicate in writing. It also frequently happens because students have not yet mastered the college success skills of time management, prioritization, and focus. In addition, some students value the ethos and authority of the writing of experts, even at the cost of valuing their own words, phrasing, and ideas. They may be afraid to say things in their own way. But college is partly about students finding their own voices and building confidence in communicating. Students should remember that quotes and sources shouldn’t drive their papers. Their own original ideas should.

Definitions

Plagiarism originates from the Latin word, plagiarius (“kidnapper”). In an intellectual sense, plagiarism means the abduction of someone else’s words, ideas, or thoughts.

The Modern Language Association provides the following discussion on plagiarism in The MLA Handbook, Eighth Edition:

Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary defines plagiarizing as committing “literary theft.” Plagiarism is presenting another person’s ideas, information, expressions, or entire work as one’s own. It is thus a kind of fraud: deceiving others to gain something of value. While plagiarism only sometimes has legal repercussions (e.g., when it involves copyright infringement—violating an author’s exclusive legal right to publication), it is always a serious moral and ethical offense. (MLA 6-7)

Simply put, plagiarism is the uncredited use (both intentional and unintentional) of the words, ideas, or thoughts of another.

Generally, there are three reasons individuals are tempted to commit plagiarism:

- Lack of confidence in own ideas, voice, and/or writing abilities.

- Lack of interest in a subject or writing task.

- Poor time management.

Types of Plagiarism

There are two types of plagiarism: intentional and unintentional.

Intentional plagiarism occurs when a writer intentionally uses the words or ideas of another without giving credit. Examples of this range from purchasing an essay off the Internet or from a fellow student and handing it in as original work to copying and pasting portions of a source into original work without giving credit. Intentional plagiarism also includes rewording the ideas and substance of a source and failing to attribute the original.

Unintentional plagiarism usually occurs because students are unsure how to incorporate others’ ideas into their own, do not know how to properly cite sources, or do not give themselves enough time with the research and writing process.

|

Intentional |

Unintentional |

|

|

To maintain integrity, make intentional choices when you integrate sources into your writing, use attributions to indicate when you include the words, ideas, or thoughts of another, and properly cite those sources.

Strategies to Avoid Plagiarism

- Cite your sources! This will be discussed in detail in the next chapter.

- Make your ideas the driving force behind your writing.

- Establish authorial voice.

- Keep detailed research notes and build an annotated bibliography as you research. Better to have a source and not need it than need a source and not have it.

- When in doubt, cite. You will not be penalized for citing. The same cannot be said for failing to cite.

- Use signal phrases.

- Utilize resources:

-

- This textbook.

- Your instructor.

- Writing tutors.

- Purdue University Online Writing Lab (OWL).

AI and Plagiarism

Artificial intelligence is everywhere these days–from chatbots and search engines, to audio and video tools. The world of writing, and student papers in particular, is no exception. While there may be legitimate uses for these tools—if you use ChatGPT or other AI/large language models to create written content for any of your classes, you could be guilty of plagiarizing.

Large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT are built upon massive databases of text scraped from sources like books and journals, but also blogs and social media sites. When you prompt an LLM with a question, the program draws upon its data to provide the most likely answer. Despite being described as “artificial intelligence”, these LLMs are not thinking—they are using statistical analysis to predict the most likely response. Essentially, LLMs work like the suggestions you see when typing out a text message.

As much of the data used to build LLMs was taken from original sources without attribution (or attention to copyright), some might argue that LLMs are themselves plagiarism machines. Regardless, content derived from LLMs cannot be considered truly original. Submitting work that is not your own is the very definition of plagiarism.

For guidance on what NOT to do within your courses, here is a list of things to avoid. (Note: This is subject to your instructor’s guidance! Some instructors are adapting and using AI as part of the learning experience, so always check with your instructor if you are unsure of what to do.)

- Do not use ChatGPT or other AI tools to produce responses to discussion prompts, essays, bibliographies, or any other written work you are asked to create for a class.

- Do not ask AI writing tools to edit your work for you. Doing so is akin to asking your writing tutor to fix all your mistakes. This is still cheating, and you should not do it.

- Avoid the temptation to ask LLMs to generate a list of sources for your paper on a particular topic. While it’s possible for an LLM to act as a jumping off point for further research/study, the tools are prone to hallucination—they will provide information that sounds correct but is entirely made up. While this is not technically plagiarism, using faulty information in your writing will certainly result in a bad grade.

Of course, completing assignments that specifically allow or require the use of AI would not be considered plagiarism. If you aren’t sure whether AI is allowed for an assignment, you should consult your instructor.

Remember that at many institutions, the punishment for plagiarism can be as severe as expulsion. Additionally, keep in mind that your instructors have likely read hundreds of thousands of words of student writing. AI-assisted writing will not be difficult for them to spot.

Ultimately, the only way to become a truly skilled writer is by writing, as much as you can and as often as you can. Furthermore, the purpose of academics is to engage with the material and draw your own conclusions. Don’t cheat yourself of the chance to become great by using a bot to think for you!

It is your instructor’s responsibility to teach you why and how to integrate other voices into your conversations and guide you in developing skills of attribution and citation; the next section of this chapter is devoted to these skills too. It is your responsibility to maintain integrity by refraining from acts of intentional plagiarism and avoiding instances of unintentional plagiarism. Remember, your instructors do not expect your writing voice to sound like that of scholarly sources. They expect writing that is appropriate for the course level in which you are working. To maintain integrity, make intentional choices when you integrate sources into your writing, use attributions to indicate when you include the words, ideas, or thoughts of another, and properly cite those sources.

It is your instructor’s responsibility to teach you why and how to integrate other voices into your conversations and guide you in developing skills of attribution and citation; the next section of this chapter is devoted to these skills too. It is your responsibility to maintain integrity by refraining from acts of intentional plagiarism and avoiding instances of unintentional plagiarism. Remember, your instructors do not expect your writing voice to sound like that of scholarly sources. They expect writing that is appropriate for the course level in which you are working. To maintain integrity, make intentional choices when you integrate sources into your writing, use attributions to indicate when you include the words, ideas, or thoughts of another, and properly cite those sources.

STEP 8: How Do I Format My Paper?

General Formatting Guidelines

- Font: Your paper should be written in 12-point Times New Roman text.

- Line Spacing: All text in your paper should be double-spaced. There should be no extra spaces between any of the lines, which requires an extra step to remove in Microsoft Word. Watch this video for the steps.

- Margins: All page margins (top, bottom, left, and right) should be 1 inch. All text should be left-justified. Microsoft will default to this; do not change it.

- Indentation: The first line of every paragraph should be indented 0.5 inches. Microsoft will default to this; do not change it.

- Page Numbers: The header should include your last name, followed by a space and the page number. Your pages should be numbered with Arabic numerals (1, 2, 3…) and should start with the number 1 on your title page. Page numbers appear in the header of the document. To create page numbers in Microsoft Word, click the “Insert” button; then click “Page Number”; “Top of Page”; “Plain Number 3.” Place your cursor next to the number; type your last name and space. The page number with your last name will appear on every page.

- Use of Italics: In MLA style, you should italicize (rather than underline) the titles of books, plays, or other standalone works. You should also italicize (rather than underline) words or phrases you want to lend particular emphasis—though you should do this rarely.

- Sentence Spacing: Include just one single space after a period before the next sentence: “Mary went to the store. She bought some milk. Then she went home.”

- The first page: Like the rest of your paper, everything on your first page, even the headers, should be double-spaced. The following information should be left-justified in regular font at the top of the first page (in the main part of the page, not the header):

- on the first line, your first and last name

- on the second line, your instructor’s name

- on the third line, the name of the class

- on the fourth line, the due date in the following format: 15 May 2025

- The title: After the header, the next double-spaced line should include the title of your paper. This should be centered and in title case, and it should not be bolded, underlined, or italicized (unless it includes the name of a book, in which case just the book title should be italicized).

- The Oxford Comma: The Oxford comma (also called the serial comma) is the comma that comes after the second-to-last item in a series or list. For example: The UK includes the countries of England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland. In the previous sentence, the comma immediately after “Wales” is the Oxford comma. In general writing conventions, whether the Oxford comma should be used is actually a point of fervent debate among passionate grammarians. However, it’s a requirement in MLA style, so double-check all your lists and series to make sure you include it!

Click here for a template already set up in MLA format. You just have to start typing!

Key Takeaways

- The 8 steps for researching a topic are:

- Narrow your topic

- Identify the audience

- Understand the difference in types of resources

- Primary vs. secondary

- Popular vs. Trade vs. Scholarly

- Use efficient methods to search for sources in databases and on the Internet

- Evaluate sources for quality

- Quote, paraphrase, and summarize accurately

- Avoid plagiarism. Plagiarism is using someone else’s work and presenting it as your own. This includes using AI to create or edit your own work.

- Format your writing using MLA Style guidelines (covered in this chapter and in Chapter 7: MLA Format)

Attributions

Writing Unleashed, version 3.0, by is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Popular, Scholarly, or Trade? By University of Texas Libraries is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

Academic Integrity at the University of Minnesota by University of Minnesota Libraries is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0

Narrowing and Developing by Excelsior Online Writing Lab (OWL) is licensed under a CC BY 4.0

Tools for Evaluating Sources by Lumen Learning is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Evaluating Resources and Misinformation by University of Chicago Library is licensed under CC BY 4.0

13.6: Quotation, Paraphrase, and Summary by Heather Ringo & Athena Kashyap (ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative) is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0

The Word on College Reading and Writing by Carol Burnell, Jaime Wood, Monique Babin, Susan Pesznecker, and Nicole Rosevear is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0

File: Primary Sources.png by Wikipedia Commons is licensed under CC BY 4.0

The Writing Textbook by Josh Woods, editor and contributor, as well as an unnamed author (by request from the original publisher), and other authors named separately is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Media Attributions

- woman in brown sweater covering her face with her hand © Dev Asangbam

- Narrowing Topic © Teaching & Learning, Ohio State University Libraries is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Man presenting power point to small audience in start-up office © Matthew Osborn

- Classroom © Kenny Eliason

- Concert Audience © Nicholas Green

- Graphic showing what databases contain © Shelley Decker is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Abraham Lincoln Quote © Ray MacLean is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- C.R.A.A.P. Test Acronym Explained © Shelley Decker is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Domain Name Differences © adstarkel is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- 9447619508_191f43abbb_w © QuotesEverlasting is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Plagiarism Angel and Devil © Pixy is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license

- MLA Style Quick Guide © Lone Star College is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Sample Paper in MLA Format © Riana Saint

- Quote © Inspirational Quotes is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license