Chapter 5.6 Argument

Argument

Why argue? We don’t always argue to win. Yes, you read that correctly. Argumentation isn’t always about being “right.” We argue to express opinions and explore new ideas. When writing an argument, your goal is to convince an audience that your opinions and ideas are worth consideration and discussion.

When instructors use the word “argument,” they’re talking about defending a certain point of view through writing or speech. Usually called a “claim,” this point of view is concerned with an issue that doesn’t have a fixed right or wrong answer. Also, this argument should not only be concerned with personal opinion (e.g., I really like carrots). Instead, an argument might tackle issues like abortion, capital punishment, stem cell research, or gun control. However, what distinguishes an argument from a descriptive essay or “report” is that the argument must take a stance; if you’re merely summarizing “both sides” of an issue or pointing out the “pros and cons,” you’re not really writing an argument. “Stricter gun control laws will likely result in a decrease in gun-related violence” is an argument. Note that people can and will disagree with this argument, which is precisely why so many instructors find this type of assignment so useful – these assignments make you think!

Academic arguments state an opinion. This opinion is always carefully defended with good reasoning and supported by evidence, such as facts, statistics, quotes from recognized authorities, and other types of evidence.

You won’t always win, and that’s fine. The goal of an argument is simply to:

- make a claim

- support your claim with the most credible reasoning and evidence you can muster

- hope that the reader will at least understand your position

- hope that your claim is taken seriously

What is an argument?

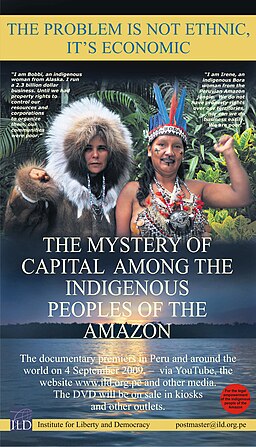

Billboards, television advertisements, documentaries, political campaign messages, bumper stickers, and social media posts are often arguments – these are messages trying to convince an audience to do something. But be aware that an academic argument is different. An academic argument requires a clear structure and use of outside evidence.

Images below show examples of argument in a variety of formats.

Elements of an Argument

- Claim: Your arguable point

- Support and Evidence: Strong reasons and materials that support your claim.

- Consideration of other Positions: Acknowledge and refute possible counterarguments.

The great thing about the argument structure is its amazingly versatility. Once you become familiar with this basic structure of the argument, you will be able to clearly argue about almost anything!

Claim

- Graffiti is vandalism, not art.

- Although it does have artistic value, graffiti is still vandalism.

- Graffiti is not simply acts of vandalism, but a true artistic form

Support

Support is a broad term in argumentation. It refers to any reasons to accept the claim, or any strategies a writer uses to effectively convey the claim to the audience. In essence, all the other parts of an argument that follow are types of support. And there are numerous other strategies for support, such as offering examples, comparisons, definitions, or discussions of causes and effects. And as you support your claims, remember not to assume that your reader automatically agrees with your statements. Convey your ideas as if you are dealing with an intelligent, critical, and reasonably skeptical reader.

- Graffiti, like traditional artistic forms such as sculpture, is art because it allows artists to express ideas through an outside medium.

- Graffiti must be considered an art form based on judgement of aesthetic qualities.

- Like all artistic forms, Graffiti has evolved, experiencing significant movements or periods.

Evidence

Evidence is any information from external references and sources that demonstrate the validity of your claim, or of your support. The best evidence in academic writing relies on information from legitimate, authoritative, or commonly accepted experts, publishers, and institutions. Mere research alone isn’t enough to function as evidence; you need to explain how the research relates to your claim or support in order for it to be real evidence. Remember you are required to cite all instances of such evidence.

For the claim and support about graffiti, we might use a quote from an expert as evidence:

- Art professor George C. Stowers argues that “larger pieces require planning and imagination and contain artistic elements like color and composition” (“Graffiti”).

Consideration Of Other Positions

Speaking of audience, there are three main strategies for addressing counterargument:

- Acknowledgement: This acknowledges the importance of a particular alternative perspective but argues that it is irrelevant to the writer’s thesis/topic. When using this strategy, the writer agrees that the alternative perspective is important but shows how it is outside of their focus.

- Accommodation: This acknowledges the validity of a potential objection to the writer’s thesis and how on the surface the objection and thesis might seem contradictory. When using this strategy, the writer goes on to argue that, however, the ideal expressed in the objection is actually consistent with the writer’s own goals if one digs deeper into the issue.

- Refutation: This acknowledges that a contrary perspective is reasonable and understandable. It does not attack differing points of view. When using this strategy, the writer responds with strong, research-based evidence showing how that other perspective is incorrect or unfounded.

Example

- Acknowledgement: Opponents of graffiti see it as criminal vandalism that creates only harm.

- Accommodation: It is true that graffiti can cause property damage, decrease tourism, and create a perception that a community is not safe.

- Refutation: However, graffiti often acts as an expression of political and social activism whose value cannot be denied. Additionally, the artistic merits of graffiti–expression, aesthetics, and movements–cannot be denied. Graffiti is art.

The entire paragraph with claim, support, evidence, and counterarguments is below:

Graffiti is not simply vandalism, but a true artistic form. Graffiti, like traditional artistic forms such as sculpture, is art because it allows artists to express ideas through an outside medium. Graffiti must be considered an art form based on judgement of aesthetic qualities. Like all artistic forms, Graffiti has evolved, experiencing significant movements or periods. Art professor George C. Stowers argues that “larger pieces require planning and imagination and contain artistic elements like color and composition” (“Graffiti”). Opponents of graffiti see it as criminal vandalism that creates only harm. It is true that graffiti can cause property damage, decrease tourism, and create a perception that a community is not safe. However, graffiti often acts as an expression of political and social activism whose value cannot be denied, particularly for marginalized communitiesBy seeing graffiti as a form of art, we can elevate the voices of communities which are silenced in more traditional forms of art.

Work Cited

“Graffiti: Art Through Vandalism.” Interactive Media Lab, University of Florida, Fall 2007, http://iml.jou.ufl.edu/projects/fall07/Sanchez/vandalism.html.

Writing Argumentative Paragraphs

Example

Example

Below is an example of the argumentation paragraph in use, followed by analysis of the components:

TV violence can have harmful psychological effects on children because those exposed to lots of it tend to adopt the values of what they see. Their constant exposure to violent images makes them unable to distinguish fantasy from reality. Smith, et al. found that children ages of 5-7 who watched more than three hours of violent television a day were 25 percent more likely to say what they saw on television was “really happening” (214). Of course, some children who watch more violent entertainment might already be attracted to violence. But Jones found that “children with no predisposition to violence were as attracted to violent images as those with a violent history” (12).

Work Cited

Booth, Wayne, et al. The Craft Research, U of Chicago Press, 2016.

Jones, Tabitha. The Study of Television, Harper Collins, 2015.

Breakdown of the argument:

Claim: “TV violence can have harmful psychological effects on children because those exposed to lots of it tend to adopt the values of what they see.”

Support: “Their constant exposure to violent images makes them unable to distinguish fantasy from reality.”

Evidence: “Smith found that children ages of 5-7 who watched more than three hours of violent television a day were 25 percent more likely to say what they saw on television was ‘really happening’ (214).”

Acknowledgment: “Of course, some children who watch more violent entertainment might already be attracted to violence. ”

Rebuttal: “But Jones found that ‘children with no predisposition to violence were as attracted to violent images as those with a violent history’ (12).”

Conclusion: Thus, parents should avoid allowing children to watch violent television movies and shows for children’s positive emotional growth.

Exercise 5.6.1

Write a fully developed paragraph using the components above: claim, support, evidence, acknowledgment, and rebuttal. For your subject, respond to one of the questions below. Suppose your audience to be other college students and your purpose to get your reader to agree with you or to better understand your point of view.

Option 1: Is it right for all college degrees to require students to pass English and math classes?

Option 2: Should colleges and universities be closed in honor of Columbus Day?

Option 3: Should community colleges allow theatrical or artistic performances on campus that could be deemed offensive?

Writing Argumentative Essays

An effective argumentative essay introduces a compelling, debatable topic to engage the reader. In an effort to persuade others to share your opinion, the writer should explain and consider all sides of an issue fairly and address counterarguments or opposing perspectives.

Back up your thesis with logical and persuasive arguments. During your pre-writing phase, outline the main points you might use to support your claim, and decide which are the strongest and most logical. Eliminate those which are based on emotion rather than fact. Your corroborating evidence should be well-researched, such as statistics, examples, and expert opinions. You can also reference personal experience. It’s a good idea to have a mixture. However, you should avoid leaning too heavily on personal experience, as you want to present an argument that appears objective as you are using it to persuade your reader.

Examples

Universal Health Care Coverage for the United States

By Scott McLean

The United States is the only modernized Western nation that does not offer publicly funded health care to all its citizens; the costs of health care for the uninsured in the United States are prohibitive, and the practices of insurance companies are often more interested in profit margins than providing health care. These conditions are incompatible with US ideals and standards, and it is time for the US government to provide universal health care coverage for all its citizens. Like education, health care should be considered a fundamental right of all US citizens, not simply a privilege for the upper and middle classes.

One of the most common arguments against providing universal health care coverage (UHC) is that it will cost too much money. In other words, UHC would raise taxes too much. While providing health care for all US citizens would cost a lot of money for every tax-paying citizen, citizens need to examine exactly how much money it would cost, and more important, how much money is “too much” when it comes to opening up health care for all. Those who have health insurance already pay too much money, and those without coverage are charged unfathomable amounts. The cost of publicly funded health care versus the cost of current insurance premiums is unclear. In fact, some Americans, especially those in lower income brackets, could stand to pay less than their current premiums.

However, even if UHC would cost Americans a bit more money each year, we ought to reflect on what type of country we would like to live in, and what types of morals we represent if we are more willing to deny health care to others on the basis of saving a couple hundred dollars per year. In a system that privileges capitalism and rugged individualism, little room remains for compassion and love. It is time that Americans realize the amorality of US hospitals forced to turn away the sick and poor. UHC is a health care system that aligns more closely with the core values that so many Americans espouse and respect, and it is time to realize its potential.

Another common argument against UHC in the United States is that other comparable national health care systems, like that of England, France, or Canada, are bankrupt or rife with problems. UHC opponents claim that sick patients in these countries often wait in long lines or long wait lists for basic health care. Opponents also commonly accuse these systems of being unable to pay for themselves, racking up huge deficits year after year. A fair amount of truth lies in these claims, but Americans must remember to put those problems in context with the problems of the current US system as well. It is true that people often wait to see a doctor in countries with UHC, but we in the United States wait as well, and we often schedule appointments weeks in advance, only to have onerous waits in the doctor’s “waiting rooms.”

Critical and urgent care abroad is always treated urgently, much the same as it is treated in the United States. The main difference there, however, is cost. Even health insurance policy holders are not safe from the costs of health care in the United States. Each day an American acquires a form of cancer, and the only effective treatment might be considered “experimental” by an insurance company and thus is not covered. Without medical coverage, the patient must pay for the treatment out of pocket. But these costs may be so prohibitive that the patient will either opt for a less effective, but covered, treatment; opt for no treatment at all; or attempt to pay the costs of treatment and experience unimaginable financial consequences. Medical bills in these cases can easily rise into the hundreds of thousands of dollars, which is enough to force even wealthy families out of their homes and into perpetual debt. Even though each American could someday face this unfortunate situation, many still choose to take the financial risk. Instead of gambling with health and financial welfare, US citizens should press their representatives to set up UHC, where their coverage will be guaranteed and affordable.

Despite the opponents’ claims against UHC, a universal system will save lives and encourage the health of all Americans. Why has public education been so easily accepted, but not public health care? It is time for Americans to start thinking socially about health in the same ways they think about education and police services: as rights of US citizens.

Exercise 5.6.2

Discussion Questions about “Universal Health Care Coverage for the United States”

- What is the author’s main claim in this essay?

- Does the author fairly and accurately present counterarguments to this claim? Explain your answer using evidence from the essay.

- Does the author provide sufficient background information for his reader about this topic? Point out at least one example in the text where the author provides background on the topic. Is it enough?

- Does the author provide a course of action in his argument? Explain your response using specific details from the essay.

Key Takeaways

- Academic argument takes a stance or a position on the issue, stating an opinion about that issue.

- In academic writing, an argument includes a claim, support and evidence, and consideration of other positions.

- A claim is the position on the issue. Support refers to the reasons that the claim is correct, and evidence is the references that prove the support and claim.

- The three main parts of a counterargument are acknowledgement, accommodation and refutation.

Attributions

The Writing Textbook by Josh Woods, editor and contributor, as well as an unnamed author (by request from the original publisher), and other authors named separately is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Writing Unleashed is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Media Attributions

- Bumper Stickers © Hiàn is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Podcast host, Dorian Djougoue © Tim Mossholder

- Poster for Documentary The Mystery of Capital among the Indigenous Peoples of the Amazon © I4LD 1 is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Billboard and posters advertising Coach © Yao Hu

- Banksy Graffiti © Chris Devers is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license