Chapter 8 Linguistic Diversity & Oppression

Englishes, not “English”

As journalist Robert MacNeil puts it, “Language reinforces feelings of social superiority or inferiority; it creates insiders and outsiders.” Stigmatized forms of English—whose users made to feel as “outsiders” to typical academic writing—are typically connected to marginalized communities, such as communities of color, non-native English learners, and low-income or working-class communities.

Exercise 8.1

Consider – how do you think you have benefitted or been limited by the language(s) that you have used in school? In what ways have you felt like an insider or an outsider?

“If we took a sample of everyday conversational speech, we would find that there are virtually no speakers who consistently speak formal standard English as prescribed in the grammar books. In fact, it is not unusual for the same person who prescribes a formal standard English form to violate standard usage in ordinary conversation.”

In other words, no one perfectly speaks in Dominant American English, which we will refer to as DAE. DAE is also commonly known as “Standard American English.” Even your professors make common speech “errors”. Try this test. See how many times members of your college faculty say “there’s” when they should have said “there are.” No one speaks like a textbook—and that’s a good thing!

Contrary to the myth of standard languages, some facts to keep in mind about language include:

- Language is complex and diverse.

- Language is not a moral marker.

- Language is not an intellectual marker.

- Language serves to communicate between people.

- Language changes across time and place.

- Language using correct DAE doesn’t equal strong writing, and vice versa.

Exercise 8.2

Have you ever written anything for school which sounds like your everyday speech? What are some parts of your speech which you feel you can or can’t express in academic writing? Why?

Why Dominant American English (DAE)?

If it’s true that DAE is just a myth, then why are we told to write this way, to write in a way that no one speaks? What might be the value of writing how you speak, and how might we begin to do this? How do we decide how we should write, in and outside of academic settings? There’s not a single answer, though we’ll try and answer some of these questions in the sections below. But for now, it’s best to say “it depends”—it depends on who you are as a writer and who you are writing for. Consider what Vershawn Ashanti Young writes below about what “good writin’” should mean in his piece “Should Writers Use They Own English” (an essay published in an academic journal: The Iowa Journal of Cultural Studies):

“we need to enlarge our perspective about what good writin is and how good writin can look at work, at home, and at school. The narrow, prescriptive lens be messin writers and readers all the way up, cuz we all been taught to respect the dominant way to write, even if we don’t, can’t, or won’t ever write that one way ourselves. That be hegemony. Internalized oppression. Linguistic self-hate. But we should be mo flexible, mo acceptin of language diversity, language expansion, and creative language usage from ourselves and from others both in formal and informal settings”

Exercises

1.) Thinking with Young’s quote, how would you define “good writin’”—without resorting to grammar or so-called “perfect” writing?

2.) Read this excerpt below from novelist Amy Tan’s piece, “Mother Tongue,” where she describes writing her first novel.

“It wasn’t until 1985 that I finally began to write fiction. And at first I wrote using what I thought to be wittily crafted sentences, sentences that would finally prove I had mastery over the English language. Here’s an example from the first draft of a story that later made its way into The Joy Luck Club, but without this line: “That was my mental quandary in its nascent state.” A terrible line, which I can barely pronounce.”

While written in so-called “perfect English,” Tan describes her sentence here from her story’s first draft as “terrible.” Why might this be a “terrible” line? How would you make it better?

For many people, learning DAE is seen as one way to challenge racism and classism, since it means helping marginalized people acquire a dominant way of speaking or writing. And yet, using DAE does not inherently protect marginalized individuals from racism or classism. Students of color who submit work in “perfect” DAE can still face skepticism from instructors about whether they actually wrote the piece and may be subjected to unfair allegations of plagiarism or use of AI because of it.

Low-income students or working-class students who have learned to speak in DAE can still be targeted for bias due to their accents or the ways in which they speak differently than they write. Even the most qualified and adept speakers or writers of DAE can still be judged unfairly due to other aspects of their identity. On the other hand, not using DAE doesn’t mean you can’t experience success in our society. For many professions, DAE isn’t necessary or beneficial—if you’re working in a trade, for instance, or working within and among a community that predominantly speaks or writes in non-DAE Englishes, then trying to use DAE will probably hinder your success.

In fact, in many circumstances, speaking Englishes beyond DAE—such as Black English or AAVE (African American Vernacular English), Spanglish (a fusion of Spanish and English), or “slanguage”—can help you succeed. Many established writers and artists who don’t use DAE regularly, and in fact speak and write in other forms of English—including rappers such as Tupac Shakur or Kendrick Lamar, academic scholars like Gloria Anzaldúa and Victor Villanueva, as well as American heads of state like President Barack Obama or President Donald Trump—have achieved great success in our culture, in large part because they don’t speak DAE. It all depends on the audience – who you are trying to reach and communicate with – as well as other aspects of your identity which may or may not benefit you with said audience. If you are trying to reach a working-class, low-income audience, for example, then using DAE may cause you to be unheard and fail to reach them.

Language and Identity

“My words were me. A teacher never was just reading my paper. That paper inter-was me, my labor, my context for writing at home or in the classroom. No matter what they said, my teachers were always grading me, not simply my papers”

— Asao Inoue, professor of rhetoric and composition in the College of Integrative Sciences and Arts at Arizona State University whose research and teaching focus on anti-racist writing assessment

A person’s language is core to who they are. When we write, we aren’t just putting words on the page; we’re putting ourselves onto the page. Our words are us—our identities, our communities, and more—even if we aren’t always aware of it.

Exercise 8.3

Think about it this way – was there ever a time you felt personally judged due to how someone – like a teacher – responded to your writing growing up? If so, why?

Denying the connection between writing and identity can have long-lasting, negative consequences. You may have started to hate writing growing up due to how someone responded to a piece of work you put a lot of time and effort—a lot of yourself—into. Consider this quote by Gloria Anzaldúa, from her book Borderlands/La Frontera, which considers the relationship between language and identity:

“If you want to really hurt me, talk badly about my language. Ethnic identity is twin skin to linguistic identity—I am my language. Until I can take pride in my language , I cannot take pride in myself. Until I can accept as legitimate Chicano Texas Spanish, Tex-Mex and all the other languages I speak, I cannot accept the legitimacy of myself. Until I am free to write bilingually and to switch codes without having always to translate, while I still have to speak English or Spanish when I would rather speak Spanglish, and as long as I have to accommodate the English speakers rather than having them accommodate me, my tongue will be illegitimate.”

Exercise 8.4

Why do you think language might be important to identity? What parts of yourself do you feel are connected to your language—what and how you speak, or write? How does language express who you are, and vice versa?

Having your “tongue” cut out is a big reason why people tend to not enjoy writing. Conversely, being able to write in a way that recognizes your language as intimately tied to identity can be one of the most rewarding activities we can participate in. Below we’ll consider some ways you can experience this too.

Code-Meshing vs. Code-Switching

One of the main ways that DAE is reinforced is through code-switching. Code-switching broadly refers to how we change the way we speak or write based on context or a situation—the spaces we’re in; the people we’re with; the specific thing we’re writing or the person we are writing to. This happens all the time, often unconsciously, and is proof of how linguistically diverse life is. Most of the time, you probably don’t even notice it. And a lot of the time, it’s blended—someone may switch codes multiple times throughout an interaction with someone else.

Sometimes we’re forced to code-switch, however, like in school or at a job. Think about it this way: if you work in a customer service position, would you be allowed to speak to customers or your boss the same way you speak to your friends? Would you write to your professor in an email or essay the same way that you would text a partner or a family member? A tiny number of us may say yes—but for most of us, the answer is probably no. Typically within “professional” spaces like work or school, we are forced to code-switch to only using DAE; if we don’t, it could mean negative consequences, like losing our jobs or receiving a poor grade.

While a lot of the code-switching we do is simply the result of the complexity of language and relationships, institutional code-switching is a major way we tend to experience linguistic oppression, since, as we’ve discussed, not all languages are treated equally within institutions. The minute we step into such spaces, we’re expected to use DAE—and if not, we’re punished. And a lot of the time, it’s marginalized people and their languages that are punished in these spaces.

Exercise 8.5

What are some words that are deemed “informal” or “unprofessional” and that you think would get you in trouble if you used them in a classroom or job, or wrote them in an essay? Why do you think these words are deemed “informal” or “unprofessional”? What might their value be if you were to use them in academic or “professional” spaces?

If code-switching in school means forcing students to write or speak only DAE, then how might we create a more empowering system for all students to write in ways natural for them and their identities?

See below how scholar Vershawn Ashanti Young code-meshes what he calls Black English with DAE in “Should Writers Use They Own English” to explain the concept of code-meshing:

“Code switching, from a linguistic perspective, is not translatin one dialect into another one. It’s blendin two or mo dialects, languages, or rhetorical forms into one sentence, one utterance, one paper. And not all the time is this blendin intentional, sometime it unintentional. And that’s the point. The two dialects sometime naturally, sometime intentionally, coexist! . . . But since so many teachers be jackin up code switching with they “speak this way at school and a different way at home,” we need a new term. I call it CODE MESHING! Code meshing is the new code switching; it’s multidialectalism and pluralingualism in one speech act, in one paper.”

As Young’s passage here demonstrates, there is no single, correct way of utilizing English because English has always been evolving. As we’ve discussed, there isn’t just “English” but many “Englishes.” But this is true for languages beyond English, too. For example, there are many kinds of Spanish, each with their own unique rules, styles, pronunciations, and purposes – Chicano Spanish is different than Mexican Spanish, for example; Dominican Spanish is different than Puerto Rican Spanish, and more. And sometimes, when we code-mesh, we blend not just one kind of dominant language like English or Spanish, but multiple, as seen in the writing of scholar Gloria Anzaldúa when writing about the complexity of Chicano Spanish:

“Chicano Spanish is a border tongue which developed naturally. Change, evolución, enriquecimiento de palabras nuevas por invención o adopción have created variants of Chicano Spanish, un nuevo lenguaje. Un lenguaje que corresponde a un modo de vivir. Chicano Spanish is not incorrect, it is a living language.”

Sometimes code-meshing keeps different languages clearly separate in a piece, either using italics or separating them by sentence; sometimes, there’s meshing occurring within the same sentence in ways that blur the lines between the two (or more). What languages you mesh, and how, is up to you as a writer. It depends a lot upon one, what you are trying to say, and two, who you are trying to reach (or not trying to reach) with your writing.

Exercise 8.6

What do you think is gained by how Young and Anzaldúa code-mesh their pieces? What might be lost if these pieces were only written in DAE? How do you think their code-meshing shapes the way a specific reader might approach or experience their writing?

Exercise 8.7

For each code or language you speak, come up with a name for it. It can be as specific and as creative as you want – maybe something you only speak with a single person or in a single place or with a single group of people. Then, try and come up with a word or phrase you feel is tied to that code or language, while labeling where you speak it or who you speak it with.

Here are some examples:

1.) “DAE” – “contextualizing”

Used: in academic writing textbooks, with college students

2.)“Slanguage” – “shit”

Used: with friends and strangers, on the street

3.) “NorCal Slang” – “hella”

Used: in the CA bay area, by college students

4.)“Basketballese” – “brick”

Used: on basketball court, with other players, or by basketball fans

5.) “Spanglish” – “googlear”

Used: at home, with family, friends, or other Spanish and English users

Now it’s your turn – try and come up with as many as you can! The more languages you contextualize, the better aware you’ll be and the more options you’ll have for code-meshing your work.

“Dash That Oxford Comma! Prestige and Stigma in Academic Writing”, by Christie Bogle is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

“Language Expresses Language”, by Eshanie Sinanan is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Anzaldúa, G. (2012). Borderlands : la frontera : the new Mestiza (4th edition 25th Anniversary edition Includes bibliographical references (p. [287]-300)). Aunt Lute Books.

Inoue, A. B., & Project Manifold (City University of New York). (2015). Antiracist writing assessment ecologies : teaching and assessing writing for a socially just future. The WAC Clearinghouse. https://torl.biblioboard.com/content/b05e6fe8-c90d-498f-9b63-28e6cfe9cd08.

Tan, A. (1990). “Mother Tongue”. The Threepenny Review, 43, 7–8. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4383908.

Wolfram, W., & Schilling-Estes, N. (2006). American English : dialects and variation (2nd ed). Blackwell Pub.

Young, V. A., (2010) “Should Writers Use They Own English?”, Iowa Journal of Cultural Studies 12(1), 110-117. doi: https://doi.org/10.17077/2168-569X.1095.

Media Attributions

- Code-Switching © NTB is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

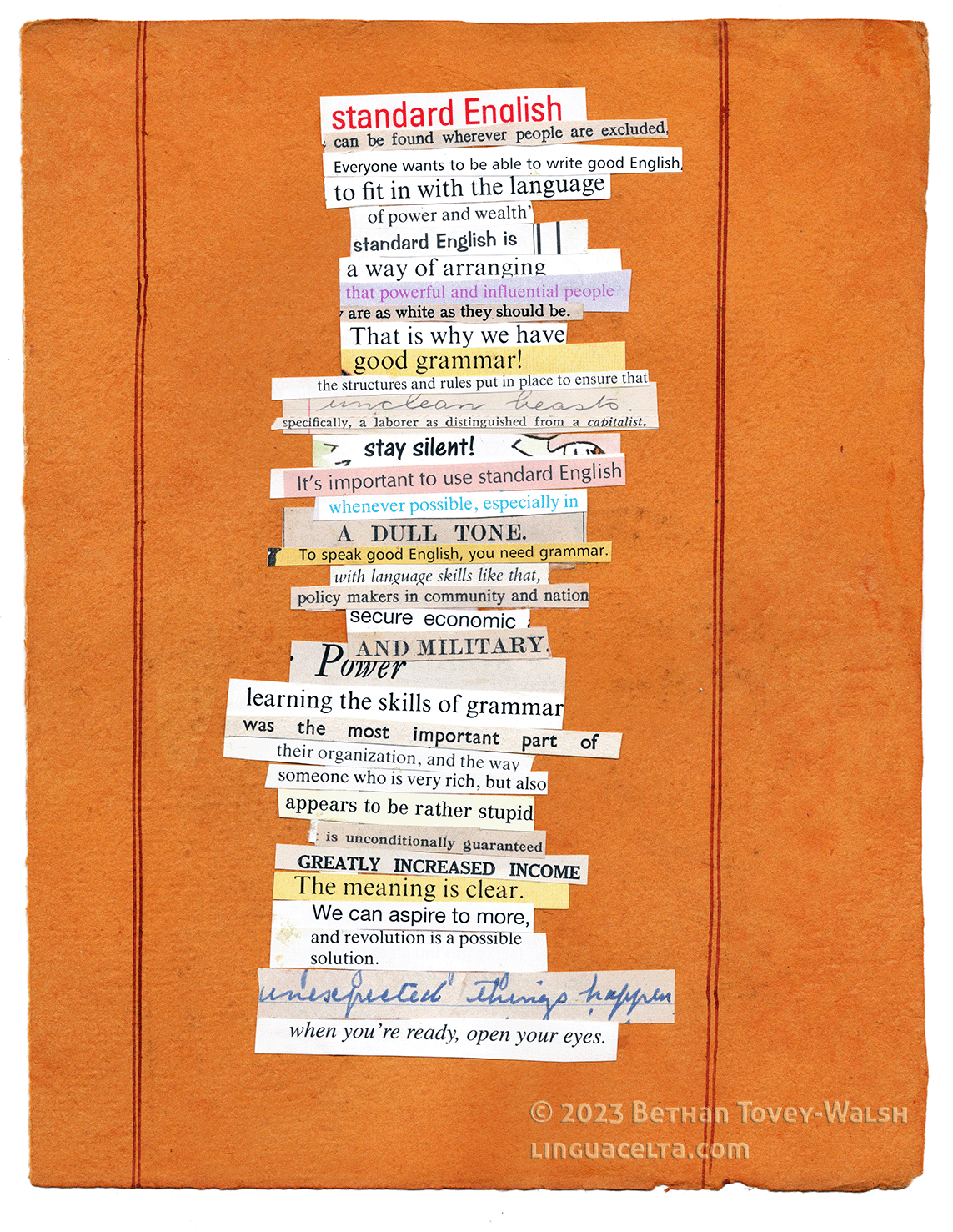

- The Meaning is Clear © Bethan Tovey-Walsh is licensed under a CC BY-ND (Attribution NoDerivatives) license

described or regarded as worthy of disgrace or great disapproval.

(of a person, group, or concept) treated as insignificant or peripheral.