Main Body

3 Chapter 3 – Argument

Kirsten DeVries

At school, at work, and in everyday life, argument is one of main ways we exchange ideas with one another. Academics, business people, scientists, and other professionals all make arguments to determine what to do or think, or to solve a problem by enlisting others to do or believe something they otherwise would not. Not surprisingly, then, argument dominates writing, and training in argument writing is essential for all college students.

This chapter will explore how to define argument, how to talk about argument, how logic works in argument, the main argument types, and a list of logical fallacies.

2. What Are the Components and Vocabulary of Argument?

4. What Are the Different Types of Argument in Writing?

5. A Repository of Logical Fallacies

1. What Is Argument?

All people, including you, make arguments on a regular basis. When you make a claim and then support the claim with reasons, you are making an argument. Consider the following:

- If, as a teenager, you ever made a case for borrowing your parents’ car using reasonable support—a track record of responsibility in other areas of your life, a good rating from your driving instructor, and promises to follow rules of driving conduct laid out by your parents—you have made an argument.

- If, as an employee, you ever persuaded your boss to give you a raise using concrete evidence—records of sales increases in your sector, a work calendar with no missed days, and personal testimonials from satisfied customers—you have made an argument.

- If, as a gardener, you ever shared your crops at a farmer’s market, declaring that your produce is better than others using relevant support—because you used the most appropriate soil, water level, and growing time for each crop—you’ve made an argument.

- If, as a literature student, you ever wrote an essay on your interpretation of a poem—defending your ideas with examples from the text and logical explanations for how those examples demonstrate your interpretation—you have made an argument.

The two main models of argument desired in college courses as part of the training for academic or professional life are rhetorical argument and academic argument. If rhetoric is the study of the craft of writing and speaking, particularly writing or speaking designed to convince and persuade, the student studying rhetorical argument focuses on how to create an argument that convinces and persuades effectively. To that end, the student must understand how to think broadly about argument, the particular vocabulary of argument, and the logic of argument. The close sibling of rhetorical argument is academic argument, argument used to discuss and evaluate ideas, usually within a professional field of study, and to convince others of those ideas. In academic argument, interpretation and research play the central roles.

However, it would be incorrect to say that academic argument and rhetorical argument do not overlap. Indeed, they do, and often. A psychologist not only wishes to prove an important idea with research, but she will also wish to do so in the most effective way possible. A politician will want to make the most persuasive case for his side, but he should also be mindful of data that may support his points. Thus, throughout this chapter, when you see the term argument, it refers to a broad category including both rhetorical and academic argument.

Before moving to the specific parts and vocabulary of argument, it will be helpful to consider some further ideas about what argument is and what it is not.

Argument vs. Controversy or Fight

Consumers of written texts are often tempted to divide writing into two categories: argumentative and non-argumentative. According to this view, to be argumentative, writing must have the following qualities: It has to defend a position in a debate between two or more opposing sides, it must be on a controversial topic, and the goal of such writing must be to prove the correctness of one point of view over another.

A related definition of argument implies a confrontation, a clash of opinions and personalities, or just a plain verbal fight. It implies a winner and a loser, a right side and a wrong one. Because of this understanding of the word “argument,” many students think the only type of argument writing is the debate-like position paper, in which the author defends his or her point of view against other, usually opposing, points of view.(

These two characteristics of argument—as controversial and as a fight—limit the definition because arguments come in different disguises, from hidden to subtle to commanding. It is useful to look at the term “argument” in a new way. What if we think of argument as an opportunity for conversation, for sharing with others our point of view on an issue, for showing others our perspective of the world? What if we think of argument as an opportunity to connect with the points of view of others rather than defeating those points of view?

One community that values argument as a type of communication and exchange is the community of scholars. They advance their arguments to share research and new ways of thinking about topics. Biologists, for example, do not gather data and write up analyses of the results because they wish to fight with other biologists, even if they disagree with the ideas of other biologists. They wish to share their discoveries and get feedback on their ideas. When historians put forth an argument, they do so often while building on the arguments of other historians who came before them. Literature scholars publish their interpretations of different works of literature to enhance understanding and share new views, not necessarily to have one interpretation replace all others. There may be debates within any field of study, but those debates can be healthy and constructive if they mean even more scholars come together to explore the ideas involved in those debates. Thus, be prepared for your college professors to have a much broader view of argument than a mere fight over a controversial topic or two.

Argument vs. Opinion

Argument is often confused with opinion. Indeed, arguments and opinions sound alike. Someone with an opinion asserts a claim that he thinks is true. Someone with an argument asserts a claim that she thinks is true. Although arguments and opinions do sound the same, there are two important differences:

- Arguments have rules; opinions do not. In other words, to form an argument, you must consider whether the argument is reasonable. Is it worth making? Is it valid? Is it sound? Do all of its parts fit together logically? Opinions, on the other hand, have no rules, and anyone asserting an opinion need not think it through for it to count as one; however, it will not count as an argument.

- Arguments have support; opinions do not. If you make a claim and then stop, as if the claim itself were enough to demonstrate its truthfulness, you have asserted an opinion only. An argument must be supported, and the support of an argument has its own rules. The support must also be reasonable, relevant, and sufficient.

Figure 3.1 “Opinion vs Argument”

Argument vs. Thesis

Another point of confusion is the difference between an argument and an essay’s thesis. For college essays, there is no essential difference between an argument and a thesis; most professors use these terms interchangeably. An argument is a claim that you must then support. The main claim of an essay is the point of the essay and provides the purpose for the essay. Thus, the main claim of an essay is also the thesis. For more on the thesis, see Chapter 4, “The Writing Process.”

Consider this as well: Most formal essays center upon one main claim (the thesis) but then support that main claim with supporting evidence and arguments. The topic sentence of a body paragraph can be another type of argument, though a supporting one, and, hence, a narrower one. Try not to be confused when professors call both the thesis and topic sentences arguments. They are not wrong because arguments come in different forms; some claims are broad enough to be broken down into a number of supporting arguments. Many longer essays are structured by the smaller arguments that are a part of and support the main argument. Sometimes professors, when they say supporting points or supporting arguments, mean the reasons (premises) for the main claim (conclusion) you make in an essay. If a claim has a number of reasons, those reasons will form the support structure for the essay, and each reason will be the basis for the topic sentence of its body paragraph.

Argument vs. Fact

Arguments are also commonly mistaken for statements of fact. This comes about because often people privilege facts over opinions, even as they defend the right to have opinions. In other words, facts are “good,” and opinions are “bad,” or if not exactly bad, then fuzzy and thus easy to reject. However, remember the important distinction between an argument and an opinion stated above: While argument may sound like an opinion, the two are not the same. An opinion is an assertion, but it is left to stand alone with little to no reasoning or support. An argument is much stronger because it includes and demonstrates reasons and support for its claim.

As for mistaking a fact for an argument, keep this important distinction in mind: An argument must be arguable. In everyday life, arguable is often a synonym for doubtful. For an argument, though, arguable means that it is worth arguing, that it has a range of possible answers, angles, or perspectives: It is an answer, angle, or perspective with which a reasonable person might disagree. Facts, by virtue of being facts, are not arguable. Facts are statements that can be definitely proven using objective data. The statement that is a fact is absolutely valid. In other words, the statement can be pronounced as definitively true or definitively false. For example, 2 + 2 = 4. This expression identifies a verifiably true statement, or a fact, because it can be proved with objective data. When a fact is established, there is no other side, and there should be no disagreement.

The misunderstanding about facts (being inherently good) and argument (being inherently problematic because it is not a fact) leads to the mistaken belief that facts have no place in an argument. This could not be farther from the truth. First of all, most arguments are formed by analyzing facts. Second, facts provide one type of support for an argument. Thus, do not think of facts and arguments as enemies; rather, they work closely together.

Explicit vs. Implicit Arguments

Arguments can be both explicit and implicit. Explicit arguments contain prominent and definable thesis statements and multiple specific proofs to support them. This is common in academic writing from scholars of all fields. Implicit arguments, on the other hand, work by weaving together facts and narratives, logic and emotion, personal experiences and statistics. Unlike explicit arguments, implicit ones do not have a one-sentence thesis statement. Implicit arguments involve evidence of many different kinds to build and convey their point of view to their audience. Both types use rhetoric, logic, and support to create effective arguments.

Exercise 1

Go on a hunt for an implicit argument in the essay, “37 Who Saw Murder Didn’t Call the Police” (https://tinyurl.com/yc35o25x) by Martin Gansberg.

1. Read the article, and take notes on it–either using a notebook or by annotating a printed copy of the text itself (for help with note-taking on reading material, see Chapter 1, “Critical Reading.” Mark or write down all the important details you find.

2. After you are finished reading, look over your notes or annotations. What do all the details add up to? Use the details you have read about to figure out what Gansberg’s implicit argument is in his essay. Write it in your own words.

Argument and Rhetoric

An argument in written form involves making choices, and knowing the principles of rhetoric allows a writer to make informed choices about various aspects of the writing process. Every act of writing takes place in a specific rhetorical situation. The most basic and important components of a rhetorical situation are

- Author of the text.

- Purpose of the text.

- Intended audience (i.e., those the author imagines will be reading the text).

- Form or type of text.

These components give readers a way to analyze a text on first encounter. These factors also help writers select their topics, arrange their material, and make other important decisions about the argument they will make and the support they will need. For more on rhetoric, see Chapter 2, “Rhetorical Analysis.”

Key Takeaways: What is an Argument?

With this brief introduction, you can see what rhetorical or academic argument is not:

- An argument need not be controversial or about a controversy.

- An argument is not a mere fight.

- An argument does not have a single winner or loser.

- An argument is not a mere opinion.

- An argument is not a statement of fact.

Furthermore, you can see what rhetorical argument is:

- An argument is a claim asserted as true.

- An argument is arguable.

- An argument must be reasonable.

- An argument must be supported.

- An argument in a formal essay is called a thesis. Supporting arguments can be called topic sentences.

- An argument can be explicit or implicit.

- An argument must be adapted to its rhetorical situation.

2. What Are the Components and Vocabulary of Argument?

Questions are at the core of arguments. What matters is not just that you believe that what you have to say is true, but that you give others viable reasons to believe it as well—and also show them that you have considered the issue from multiple angles. To do that, build your argument out of the answers to the five questions a rational reader will expect answers to. In academic and professional writing, we tend to build arguments from the answers to these main questions:

- What do you want me to do or think?

- Why should I do or think that?

- How do I know that what you say is true?

- Why should I accept the reasons that support your claim?

- What about this other idea, fact, or consideration?

- How should you present your argument?

When you ask people to do or think something they otherwise would not, they quite naturally want to know why they should do so. In fact, people tend to ask the same questions. As you make a reasonable argument, you anticipate and respond to readers’ questions with a particular part of argument:

1. The answer to What do you want me to do or think? is your conclusion: “I conclude that you should do or think X.”

2. The answer to Why should I do or think that? states your premise: “You should do or think X because . . .”

3. The answer to How do I know that what you say is true? presents your support: “You can believe my reasons because they are supported by these facts . . .”

4. The answer to Why should I accept that your reasons support your claim? states your general principle of reasoning, called a warrant: “My specific reason supports my specific claim because whenever this general condition is true, we can generally draw a conclusion like mine.”

5. The answer to What about this other idea, fact, or conclusion?acknowledges that your readers might see things differently and then responds to their counterarguments.

6. The answer to How should you present your argument? leads to the point of view, organization, and tone that you should use when making your arguments.

As you have noticed, the answers to these questions involve knowing the particular vocabulary about argument because these terms refer to specific parts of an argument. The remainder of this section will cover the terms referred to in the questions listed above as well as others that will help you better understand the building blocks of argument.

What Is a Conclusion, and What Is a Premise?

The root notion of an argument is that it convinces us that something is true. What we are being convinced of is the conclusion. An example would be this claim:

Littering is harmful.

A reason for this conclusion is called the premise. Typically, a conclusion will be supported by two or more premises. Both premises and conclusions are statements. Some premises for our littering conclusion might be these:

Littering is dangerous to animals.

Littering is dangerous to humans.

Thus, to be clear, understand that an argument asserts that the writer’s claim is true in two main parts: the premises of the argument exist to show that the conclusion is true.

Tip

Be aware of the other words to indicate a conclusion–claim, assertion, point–and other ways to talk about the premise–reason, factor, the why. Also, do not confuse this use of the word conclusion with a conclusion paragraph for an essay.

What Is a Statement?

A statement is a type of sentence that can be true or false and corresponds to the grammatical category of a declarative sentence. For example, the sentence,

The Nile is a river in northeastern Africa,

is a statement because it makes sense to inquire whether it is true or false. (In this case, it happens to be true.) However, a sentence is still a statement, even if it is false. For example, the sentence,

The Yangtze is a river in Japan,

is still a statement; it is just a false statement (the Yangtze River is in China). In contrast, none of the following sentences are statements:

Please help yourself to more casserole.

Don’t tell your mother about the surprise.

Do you like Vietnamese pho?

None of these sentences are statements because it does not make sense to ask whether those sentences are true or false; rather, they are a request, a command, and a question, respectively. Make sure to remember the difference between sentences that are declarative statements and sentences that are not because arguments depend on declarative statements.

Tip

A question cannot be an argument, yet students will often pose a question at the end of an introduction to an essay, thinking they have declared their thesis. They have not. If, however, they answer that question (conclusion) and give some reasons for that answer (premises), they then have the components necessary for both an argument and a declarative statement of that argument (thesis).

To reiterate: All arguments are composed of premises and conclusions, both of which are types of statements. The premises of the argument provide reasons for thinking that the conclusion is true. Arguments typically involve more than one premise.

What Is Standard Argument Form?

A standard way of capturing the structure of an argument, or diagramming it, is by numbering the premises and conclusion. For example, the following represents another way to arrange the littering argument:

- Littering is harmful

- Litter is dangerous to animals

- Litter is dangerous to humans

This numbered list represents an argument that has been put into standard argument form. A more precise definition of an argument now emerges, employing the vocabulary that is specific to academic and rhetorical arguments. An argument is a set of statements, some of which (the premises: statements 2 and 3 above) attempt to provide a reason for thinking that some other statement (the conclusion: statement 1) is true.

Tip

Diagramming an argument can be helpful when trying to figure out your essay’s thesis. Because a thesis is an argument, putting the parts of an argument into standard form can help sort ideas. You can transform the numbered ideas into a cohesive sentence or two for your thesis once you are more certain what your argument parts are.

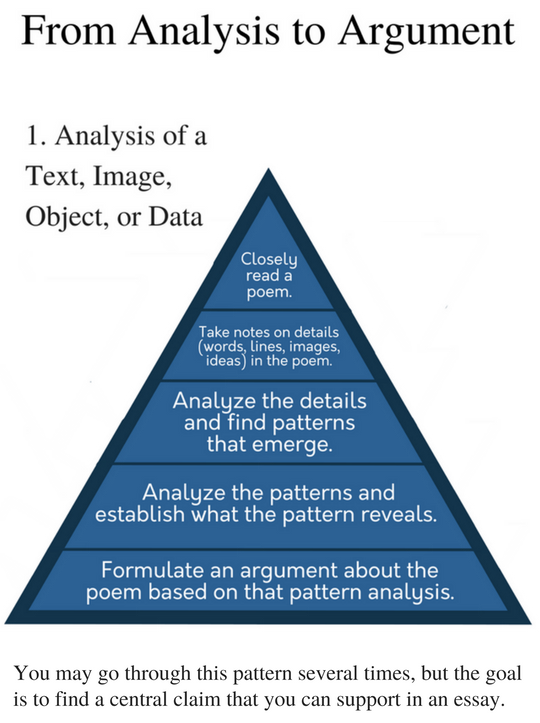

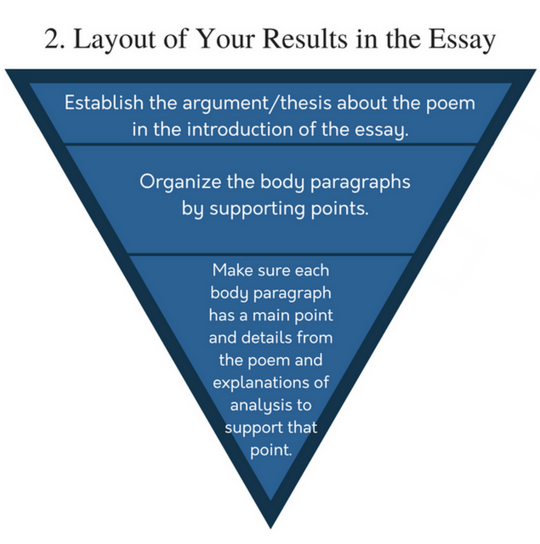

Figure 3.2 “Argument Diagram”

Recognizing arguments is essential to analysis and critical thinking; if you cannot distinguish between the details (the support) of a piece of writing and what those details are there to support (the argument), you will likely misunderstand what you are reading. Additionally, studying how others make arguments can help you learn how to effectively create your own.

What Are Argument Indicators?

While mapping an argument in standard argument form can be a good way to figure out and formulate a thesis, identifying arguments by other writers is also important. The best way to identify an argument is to ask whether a claim exists (in statement form) that a writer justifies by reasons (also in statement form). Other identifying markers of arguments are key words or phrases that are premise indicators or conclusion indicators. For example, recall the littering argument, reworded here into a single sentence (much like a thesis statement):

Littering is harmful because it is dangerous to both animals and humans.

The word “because” here is a premise indicator. That is, “because” indicates that what follows is a reason for thinking that littering is bad. Here is another example:

The student plagiarized since I found the exact same sentences on a website, and the website was published more than a year before the student wrote the paper.

In this example, the word “since” is a premise indicator because what follows is a statement that is clearly intended to be a reason for thinking that the student plagiarized (i.e., a premise). Notice that in these two cases, the premise indicators “because” and “since” are interchangeable: “because” could be used in place of “since” or “since” in the place of “because,” and the meaning of the sentences would have been the same.

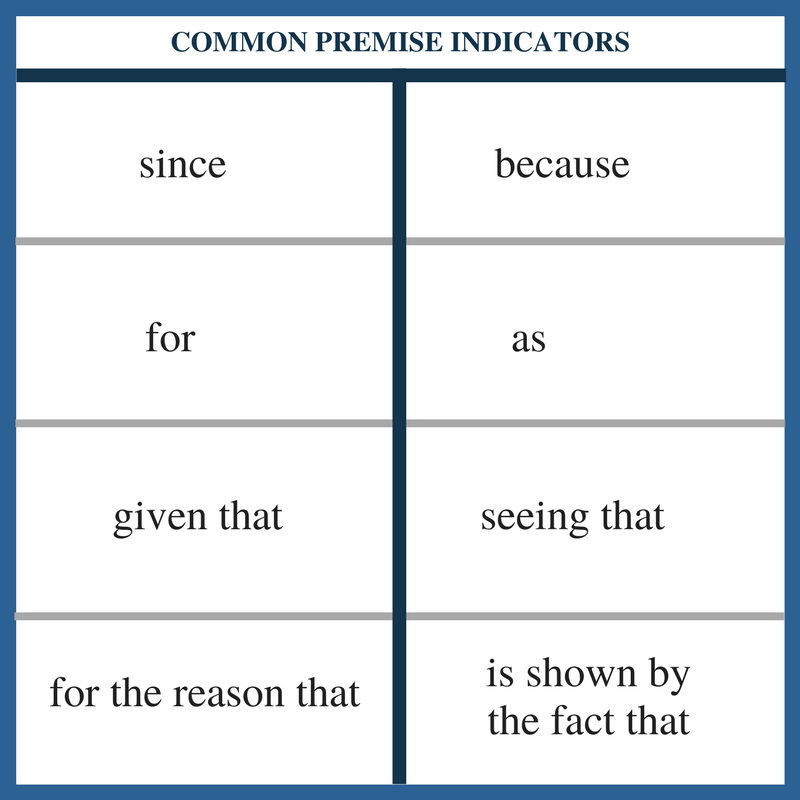

Figure 3.3 “Common Premise Indicators”

In addition to premise indicators, there are also conclusion indicators. Conclusion indicators mark that what follows is the conclusion of an argument. For example,

Bob-the-arsonist has been dead for a year, so Bob-the-arsonist didn’t set the fire at the East Lansing Starbucks last week.

In this example, the word “so” is a conclusion indicator because what follows it is a statement that someone is trying to establish as true (i.e., a conclusion). Here is another example of a conclusion indicator:

A poll administered by Gallup (a respected polling company) showed candidate X to be substantially behind candidate Y with only a week left before the vote; therefore, candidate Y will probably not win the election.

In this example, the word “therefore” is a conclusion indicator because what follows it is a statement that someone is trying to establish as true (i.e., a conclusion). As before, in both of these cases, the conclusion indicators “so” and “therefore” are interchangeable: “So” could be used in place of “therefore” or “therefore” in the place of “so,” and the meaning of the sentences would have been the same.

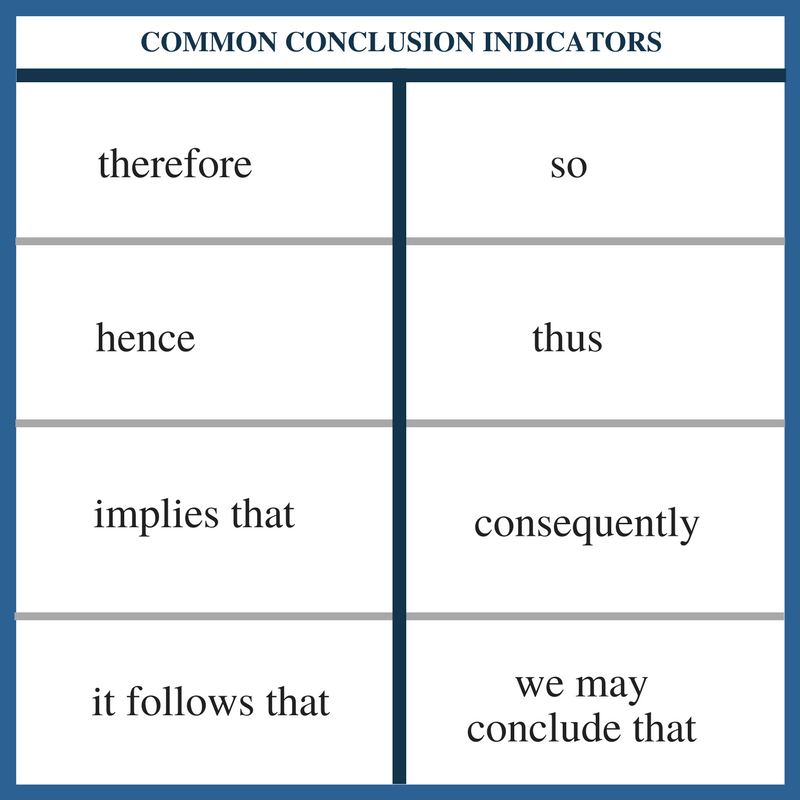

Figure 3.4 “Common Conclusion Indicators”

Exercise 2 (OPTIONAL)

Which of the following are arguments? If it is an argument, identify the conclusion (claim) of the argument. If it is not an argument, explain why not. Remember to look for the qualifying features of an argument: (1) It is a statement or series of statements, (2) it states a claim (a conclusion), and (3) it has at least one premise (reason for the claim).

- The woman with the hat is not a witch since witches have long noses, and she doesn’t have a long nose.

- I have been wrangling cattle since before you were old enough to tie your own shoes.

- Albert is angry with me, so he probably won’t be willing to help me wash the dishes.

- First, I washed the dishes, and then I dried them.

- If the road weren’t icy, the car wouldn’t have slid off the turn.

- Marvin isn’t a fireman and isn’t a fisherman, either.

- Are you seeing the rhinoceros over there? It’s huge!

- Obesity has become a problem in the US because obesity rates have risen over the past four decades.

- Bob showed me a graph with rising obesity rates, and I was very surprised to see how much they had risen.

- Marvin isn’t a fireman because Marvin is a Greyhound, which is a type of dog, and dogs can’t be firemen.

- What Susie told you is not the actual reason she missed her flight to Denver.

- Carol likely forgot to lock her door this morning because she was distracted by a clown riding a unicycle while singing Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “Simple Man.”

- No one who has ever gotten frostbite while climbing K2 has survived to tell about it; therefore, no one ever will.

What Constitutes Support?

To ensure that your argument is sound—that the premises for your conclusion are true—you must establish support. The burden of proof, to borrow language from law, is on the one making an argument, not on the recipient of an argument. If you wish to assert a claim, you must then also support it, and this support must be relevant, logical, and sufficient.

It is important to use the right kind of evidence, to use it effectively, and to have an appropriate amount of it.

- If, for example, your philosophy professor did not like that you used a survey of public opinion as your primary evidence in an ethics paper, you most likely used material that was not relevant to your topic. Rather, you should find out what philosophers count as good evidence. Different fields of study involve types of evidence based on relevance to those fields.

- If your professor has put question marks by your thesis or has written, “It does not follow,” you likely have problems with logic. Make sure it is clear how the parts of your argument logically fit together.

- If your instructor has told you that you need more analysis, suggested that you are “just listing” points or giving a “laundry list,” you likely have not included enough explanation for how a point connects to and supports your argument, which is another problem with logic, this time related to the warrants of your argument. You need to fully incorporate evidence into your argument. (See more on warrants immediately below.)

- If you see comments like “for example?,” “proof?,” “go deeper,” or “expand,” you may need more evidence. In other words, the evidence you have is not yet sufficient. One or two pieces of evidence will not be enough to prove your argument. Similarly, multiple pieces of evidence that aren’t developed thoroughly would also be flawed, also insufficient. Would a lawyer go to trial with only one piece of evidence? No, the lawyer would want to have as much evidence as possible from a variety of sources to make a viable case. Similarly, a lawyer would fully develop evidence for a claim using explanation, facts, statistics, stories, experiences, research, details, and the like.

You will find more information about the different types of evidence, how to find them, and what makes them credible in Chapter 6, “Research.” Logic will be covered later on in this chapter.

What Is the Warrant?

Above all, connect the evidence to the argument. This connection is the warrant. Evidence is not self-evident. In other words, after introducing evidence into your writing, you must demonstrate why and how this evidence supports your argument. You must explain the significance of the evidence and its function in your paper. What turns a fact or piece of information into evidence is the connection it has with a larger claim or argument: Evidence is always evidence for or against something, and you have to make that link clear.

Tip

Student writers sometimes assume that readers already know the information being written about; students may be wary of elaborating too much because they think their points are obvious. But remember, readers are not mind readers: Although they may be familiar with many of the ideas discussed, they don’t know what writers want to do with those ideas unless they indicate that through explanations, organization, and transitions. Thus, when you write, be sure to explain the connections you made in your mind when you chose your evidence, decided where to place it in your paper, and drew conclusions based on it.

What Is a Counterargument?

Remember that arguments are multi-sided. As you brainstorm and prepare to present your idea and your support for it, consider other sides of the issue. These other sides are counterarguments. Make a list of counterarguments as you work through the writing process, and use them to build your case – to widen your idea to include a valid counterargument, to explain how a counterargument might be defeated, to illustrate how a counterargument may not withstand the scrutiny your research has uncovered, and/or to show that you are aware of and have taken into account other possibilities.

For example, you might choose the issue of declawing cats and set up your search with the question should I have my indoor cat declawed? Your research, interviews, surveys, personal experiences might yield several angles on this question: Yes, it will save your furniture and your arms and ankles. No, it causes psychological issues for the cat. No, if the cat should get outside, he will be without defense. As a writer, be prepared to address alternate arguments and to include them to the extent that it will illustrate your reasoning.

Almost anything claimed in a paper can be refuted or challenged. Opposing points of view and arguments exist in every debate. It is smart to anticipate possible objections to your arguments – and to do so will make your arguments stronger. Another term for a counterargument is antithesis (i.e., the opposition to a thesis). To find possible counterarguments (and keep in mind there can be many counterpoints to one claim), ask the following questions:

- Could someone draw a different conclusion from the facts or examples you present?

- Could a reader question any of your assumptions or claims?

- Could a reader offer a different explanation of an issue?

- Is there any evidence out there that could weaken your position?

If the answer to any of these questions is yes, the next set of questions can help you respond to these potential objections:

Is it possible to concede the point of the opposition, but then challenge that point’s importance/usefulness?

- Can you offer an explanation of why a reader should question a piece of evidence or consider a different point of view?

- Can you explain how your position responds to any contradicting evidence?

- Can you put forward a different interpretation of evidence?

It may not seem likely at first, but clearly recognizing and addressing different sides of the argument, the ones that are not your own, can make your argument and paper stronger. By addressing the antithesis of your argument essay, you are showing your readers that you have carefully considered the issue and accept that there are often other ways to view the same thing.

You can use signal phrases in your paper to alert readers that you are about to present an objection. Consider using one of these phrases–or ones like them–at the beginning of a paragraph:

- Researchers have challenged these claims with…

- Critics argue that this view…

- Some readers may point to…

What Are More Complex Argument Structures?

So far you have seen that an argument consists of a conclusion and a premise (typically more than one). However, often arguments and explanations have a more complex structure than just a few premises that directly support the conclusion. For example, consider the following argument:

No one living in Pompeii could have survived the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius. The reason is simple: The lava was flowing too fast, and there was nowhere to go to escape it in time. Therefore, this account of the eruption, which claims to have been written by an eyewitness living in Pompeii, was not actually written by an eyewitness.

The main conclusion of this argument—the statement that depends on other statements as evidence but doesn’t itself provide any evidence for other statements—is

A. This account of the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius was not actually written by an eyewitness.

However, the argument’s structure is more complex than simply having a couple of premises that provide evidence directly for the conclusion. Rather, some statements provide evidence directly for the main conclusion, but some premise statements support other premise statements which then support the conclusion.

To determine the structure of an argument, you must determine which statements support which, using premise and conclusion indicators to help. For example, the passage above contains the phrase, “the reason is…” which is a premise indicator, and it also contains the conclusion indicator, “therefore.” That conclusion indicator helps identify the main conclusion, but the more important element to see is that statement A does not itself provide evidence or support for any of the other statements in the argument, which is the clearest reason statement A is the main conclusion of the argument. The next questions to answer are these: Which statement most directly supports A? What most directly supports A is

B. No one living in Pompeii could have survived the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius.

However, there is also a reason offered in support of B. That reason is the following:

C. The lava from Mt. Vesuvius was flowing too fast, and there was nowhere for someone living in Pompeii to go to escape it in time.

So the main conclusion (A) is directly supported by B, and B is supported by C. Since B acts as a premise for the main conclusion but is also itself the conclusion of further premises, B is classified as an intermediate conclusion. What you should recognize here is that one and the same statement can act as both a premise and a conclusion. Statement B is a premise that supports the main conclusion (A), but it is also itself a conclusion that follows from C. Here is how to put this complex argument into standard form (using numbers this time, as is typical for diagramming arguments):

- The lava from Mt. Vesuvius was flowing too fast, and there was nowhere for someone living in Pompeii to go to escape it in time.

- Therefore, no one living in Pompeii could have survived the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius. (from 1)

- Therefore, this account of the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius was not actually written by an eyewitness. (from 2)

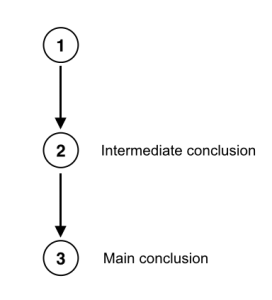

Notice that at the end of statement 2 is a written indicator in parentheses (from 1), and, likewise, at the end of statement 3 is another indicator (from 2). From 1 is a shorthand way of saying, “this statement follows logically from statement 1.” Use this convention as a way to keep track of an argument’s structure. It may also help to think about the structure of an argument spatially, as the figure below shows:

The main argument here (from 2 to 3) contains a subargument, in this case, the argument from 1 (a premise) to 2 (the intermediate conclusion). A subargument, as the term suggests, is a part of an argument that provides indirect support for the main argument. The main argument is simply the argument whose conclusion is the main conclusion.

Another type of structure that arguments can have is when two or more premises provide direct but independent support for the conclusion. Here is an example of an argument with that structure:

Wanda rode her bike to work today because when she arrived at work she had her right pant leg rolled up, which cyclists do to keep their pants legs from getting caught in the chain. Moreover, our co-worker, Bob, who works in accounting, saw her riding towards work at 7:45 a.m.

The conclusion of this argument is “Wanda rode her bike to work today”; two premises provide independent support for it: the fact that Wanda had her pant leg cuffed and the fact that Bob saw her riding her bike. Here is the argument in standard form:

- Wanda arrived at work with her right pant leg rolled up.

- Cyclists often roll up their right pant leg.

- Bob saw Wanda riding her bike towards work at 7:45.

- Therefore, Wanda rode her bike to work today. (from 1-2, 3 independently)

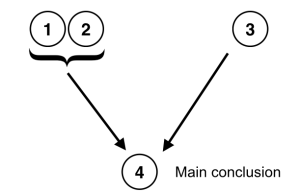

Again, notice that next to statement 4 of the argument is an indicator of how each part of the argument relates to the main conclusion. In this case, to avoid any ambiguity, you can see that the support for the conclusion comes independently from statements 1 and 2, on the one hand, and from statement 3, on the other hand. It is important to point out that an argument or subargument can be supported by one or more premises, the case in this argument because the main conclusion (4) is supported jointly by 1 and 2, and singly by 3. As before, we can represent the structure of this argument spatially, as the figure below shows:

There are endless argument structures that can be generated from a few simple patterns. At this point, it is important to understand that arguments can have different structures and that some arguments will be more complex than others. Determining the structure of complex arguments is a skill that takes some time to master, rather like simplifying equations in math. Even so, it may help to remember that any argument structure ultimately traces back to some combination of premises, intermediate arguments, and a main conclusion.

Exercise 3 (OPTIONAL)

Write the following arguments in standard form. If any arguments are complex, show how each complex argument is structured using a diagram like those shown just above.

1. There is nothing wrong with prostitution because there is nothing wrong with consensual sexual and economic interactions between adults. Moreover, there is no difference between a man who goes on a blind date with a woman, buys her dinner and then has sex with her and a man who simply pays a woman for sex, which is another reason there is nothing wrong with prostitution.

2. Prostitution is wrong because it involves women who have typically been sexually abused as children. Proof that these women have been abused comes from multiple surveys done with female prostitutes that show a high percentage of self-reported sexual abuse as children.

3. Someone was in this cabin recently because warm water was in the tea kettle and wood was still smoldering in the fireplace. However, the person couldn’t have been Tim because Tim has been with me the whole time. Therefore, someone else must be in these woods.

4. Someone can be blind and yet run in the Olympic Games since Marla Runyan did it at the 2000 Sydney Olympics.

5. The train was late because it had to take a longer, alternate route seeing as the bridge was out.

6. Israel is not safe if Iran gets nuclear missiles because Iran has threatened multiple times to destroy Israel, and if Iran had nuclear missiles, it would be able to carry out this threat. Furthermore, since Iran has been developing enriched uranium, it has the key component needed for nuclear weapons; every other part of the process of building a nuclear weapon is simple compared to that. Therefore, Israel is not safe.

7. Since all professional hockey players are missing front teeth, and Martin is a professional hockey player, it follows that Martin is missing front teeth. Because almost all professional athletes who are missing their front teeth have false teeth, it follows that Martin probably has false teeth.

8. Anyone who eats the crab rangoon at China Food restaurant will probably have stomach troubles afterward. It has happened to me every time; thus, it will probably happen to other people as well. Since Bob ate the crab rangoon at China Food restaurant, he will probably have stomach troubles afterward.

9. Lucky and Caroline like to go for runs in the afternoon in Hyde Park. Because Lucky never runs alone, any time Albert is running, Caroline must also be running. Albert looks like he has just run (since he is panting hard), so it follows that Caroline must have run, too.

10. Just because Linda’s prints were on the gun that killed Terry and the gun was registered to Linda, it doesn’t mean that Linda killed Terry since Linda’s prints would certainly be on her own gun, and someone else could have stolen her gun and used it to kill Terry.

Key Takeaways: Components of Vocabulary and Argument

- Conclusion—a claim that is asserted as true. One part of an argument.

- Premise—a reason behind a conclusion. The other part of an argument. Most conclusions have more than one premise.

- Statement—a declarative sentence that can be evaluated as true or false. The parts of an argument, premises and the conclusion, should be statements.

- Standard Argument Form—a numbered breakdown of the parts of an argument (conclusion and all premises).

- Premise Indicators—terms that signal that a premise, or reason, is coming.

- Conclusion Indicator—terms that signal that a conclusion, or claim, is coming.

- Support—anything used as proof or reasoning for an argument. This includes evidence, experience, and logic.

- Warrant—the connection made between the support and the reasons of an argument.

- Counterargument—an opposing argument to the one you make. An argument can have multiple counterarguments.

- Complex Arguments–these are formed by more than individual premises that point to a conclusion. Complex arguments may have layers to them, including an intermediate argument that may act as both a conclusion (with its own premises) and a premise (for the main conclusion).

3. What Is Logic?

Logic, in its most basic sense, is the study of how ideas reasonably fit together. In other words, when you apply logic, you must be concerned with analyzing ideas and arguments by using reason and rational thinking, not emotions or mysticism or belief. As a dedicated field of study, logic belongs primarily to math, philosophy, and computer science; in these fields, one can get professional training in logic. However, all academic disciplines employ logic: to evaluate evidence, to analyze arguments, to explain ideas, and to connect evidence to arguments. One of the most important uses of logic is in composing and evaluating arguments.

The study of logic divides into two main categories: formal and informal. Formal logic is the formal study of logic. In other words, in math or philosophy or computer science, if you were to take a class on logic, you would likely be learning formal logic. The purpose of formal logic is to eliminate any imprecision or lack of objectivity in evaluating arguments. Logicians, scholars who study and apply logic, have devised a number of formal techniques that accomplish this goal for certain classes of arguments. These techniques can include truth tables, Venn diagrams, proofs, syllogisms, and formulae. The different branches of formal logic include, but are not limited to, propositional logic, categorical logic, and first order logic.

Informal logic is logic applied outside of formal study and is most often used in college, business, and life. According to The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy,

For centuries, the study of logic has inspired the idea that its methods might be harnessed in efforts to understand and improve thinking, reasoning, and argument as they occur in real life contexts: in public discussion and debate; in education and intellectual exchange; in interpersonal relations; and in law, medicine, and other professions. Informal logic is the attempt to build a logic suited to this purpose. It combines the study of argument, evidence, proof and justification with an instrumental outlook which emphasizes its usefulness in the analysis of real life arguing.

When people apply the principles of logic to employ and evaluate arguments in real life situations and studies, they are using informal logic.

Why Is Logic Important?

Logic is one of the most respected elements of scholarly and professional thinking and writing. Consider that logic teaches us how to recognize good and bad arguments—not just arguments about logic, any argument. Nearly every undertaking in life will ultimately require that you evaluate an argument, perhaps several. You are confronted with a question: “Should I buy this car or that car?” “Should I go to this college or that college?” “Did that scientific experiment show what the scientist claims it did?” “Should I vote for the candidate who promises to lower taxes, or for the one who says she might raise them?” Your life is a long parade of choices.

When answering such questions, to make the best choices, you often have only one tool: an argument. You listen to the reasons for and against various options and must choose among them. Thus, the ability to evaluate arguments is an ability useful in everything that you will do—in your work, your personal life, and your deepest reflections. This is the job of logic.

If you are a student, note that nearly every discipline–be it a science, one of the humanities, or a study like business–relies upon arguments. Evaluating arguments is the most fundamental skill common to math, physics, psychology, history, literary studies, and any other intellectual endeavor. Logic alone tells you how to evaluate the arguments of any discipline.

The alternative to developing logic skills is to be always at the mercy of bad reasoning and, as a result, bad choices. Worse, you can be manipulated by deceivers. Speaking in Canandaigua, New York, on August 3, 1857, the escaped slave and abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass observed,

Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will. Find out just what any people will quietly submit to and you have found out the exact measure of injustice and wrong which will be imposed upon them, and these will continue till they are resisted with either words or blows, or with both. The limits of tyrants are prescribed by the endurance of those whom they oppress.

Add this to Frederick Douglass’s words: If you find out just how much a person can be deceived, that is just how far she will be deceived. The limits of tyrants are also prescribed by the reasoning abilities of those they aim to oppress. What logic teaches you is how to demand and recognize good reasoning, and, hence, avoid deceit. You are only as free as your powers of reasoning enable.

The remaining part of this logic section will concern two types of logical arguments—inductive and deductive—and the tests of those arguments, including validity, soundness, reliability, and strength, so that you can check your own arguments and evaluate the arguments of others, no matter if those arguments come from the various academic disciplines, politics, the business world, or just discussions with friends and family.

What Is Deductive Argument?

A deductive argument is an argument whose conclusion is supposed to follow from its premises with absolute certainty, thus leaving no possibility that the conclusion doesn’t follow from the premises. If a deductive argument fails to guarantee the truth of the conclusion, then the deductive argument can no longer be called a deductive argument.

The Tests of Deductive Arguments: Validity and Soundness

So far in this chapter, you have learned what arguments are and how to determine their structure, including how to reconstruct arguments in standard form. But what makes an argument good or bad? There are four main ways to test arguments, two of which are for deductive arguments. The first test for deductive arguments is validity, a concept that is central to logical thinking. Validity relates to how well the premises support the conclusion and is the golden standard that every deductive argument should aim for. A valid argument is an argument whose conclusion cannot possibly be false, assuming that the premises are true. Another way to put this is as a conditional statement: A valid argument is an argument in which if the premises are true, the conclusion must be true. Here is an example of a valid argument:

- Violet is a dog.

- Therefore, Violet is a mammal. (from 1)

You might wonder whether it is true that Violet is a dog (maybe she’s a lizard or a buffalo—you have no way of knowing from the information given). But, for the purposes of validity, it doesn’t matter whether premise 1 is actually true or false. All that matters for validity is whether the conclusion follows from the premise. You can see that the conclusion—that Violet is a mammal—does seem to follow from the premise—that Violet is a dog. That is, given the truth of the premise, the conclusion has to be true. This argument is clearly valid because if you assume that “Violet is a dog” is true, then, since all dogs are mammals, it follows that “Violet is a mammal” must also be true. Thus, whether an argument is valid has nothing to do with whether the premises of the argument are actually true. Here is an example where the premises are clearly false, yet the argument is valid:

- Everyone born in France can speak French.

- Barack Obama was born in France.

- Therefore, Barack Obama can speak French. (from 1-2)

This is a valid argument. Why? Because when you assume the truth of the premises (everyone born in France can speak French, and Barack Obama was born in France) the conclusion (Barack Obama can speak French) must be true. Notice that this is so even though none of these statements is actually true. Not everyone born in France can speak French (think about people who were born there but then moved somewhere else where they didn’t speak French and never learned it), and Barack Obama was not born in France, but it is also false that Obama can speak French. However, the argument is still valid even though neither the premises nor the conclusion is actually true. That may sound strange, but if you understand the concept of validity, it is not strange at all. Remember: validity describes the relationship between the premises and conclusion, and it means that the premises imply the conclusion, whether or not that conclusion is true.

To better understand the concept of validity, examine this example of an invalid argument:

- George was President of the United States.

- Therefore, George was elected President of the United States. (from 1)

This argument is invalid because it is possible for the premise to be true and yet the conclusion false. Here is a counterexample to the argument. Gerald Ford was President of the United States, but he was never elected president because Ford replaced Richard Nixon when Nixon resigned in the wake of the Watergate scandal. Therefore, it does not follow that just because someone is President of the United States that he was elected President of the United States. In other words, it is possible for the premise of the argument to be true and yet the conclusion false. This means that the argument is invalid. If an argument is invalid, it will always be possible to construct a counterexample to show that it is invalid (as demonstrated in the Gerald Ford scenario). A counterexample is simply a description of a scenario in which the premises of the argument are all true while the conclusion of the argument is false.

Exercise 4

Determine whether the following arguments are valid by using an informal test of validity. (You can copy and paste the text into your document.) In other words, ask whether you can imagine a scenario in which the premises are both true and yet the conclusion is false. For each argument do the following: (1) If the argument is valid, explain your reasoning, and (2) if the argument is invalid, provide a counterexample. Remember, this is a test of validity, so you may assume all premises are true (even if you know or suspect they are not in real life) for the purposes of this assignment.

1. Katie is a human being. Therefore, Katie is smarter than a chimpanzee.

2. Bob is a fireman. Therefore, Bob has put out fires.

3. Gerald is a mathematics professor. Therefore, Gerald knows how to teach mathematics.

4. Monica is a French teacher. Therefore, Monica knows how to teach French.

5. Bob is taller than Susan. Susan is taller than Frankie. Therefore, Bob is taller than Frankie.

6. Craig loves Linda. Linda loves Monique. Therefore, Craig loves Monique.

7. Orel Hershizer is a Christian. Therefore, Orel Hershizer communicates with God.

8. All Muslims pray to Allah. Muhammad is a Muslim. Therefore, Muhammad prays to Allah.

9. Some protozoa are predators. No protozoa are animals. Therefore, some predators are not animals.

10. Charlie only barks when he hears a burglar outside. Charlie is barking. Therefore, there must be a burglar outside.

A good deductive argument is not only valid but also sound. A sound argument is a valid argument that has all true premises. That means that the conclusion, or claim, of a sound argument will always be true because if an argument is valid, the premises transmit truth to the conclusion on the assumption of the truth of the premises. If the premises are actually true, as they are in a sound argument, and since all sound arguments are valid, we know that the conclusion of a sound argument is true. The relationship between soundness and validity is easy to specify: all sound arguments are valid arguments, but not all valid arguments are sound arguments.

Professors will expect sound arguments in college writing. Philosophy professors, for the sake of pursuing arguments based on logic alone, may allow students to pursue unsound arguments, but nearly all other professors will want sound arguments. How do you make sure that all the premises of your argument are true? How can we know that Violet is a dog or that littering is harmful to animals and people? Answers to these questions come from evidence, often in the form of research.

Tip

One way to counter another’s argument is to question his premises and test them for soundness. If you find that one or more premise is unsound, you can add that information–and your explanations–to the support of your own argument.

One way to test the accuracy of a premise is to apply the following questions:

- Is there a sufficient amount of data?

- What is the quality of the data?

- Has additional data been missed?

- Is the data relevant?

- Are there additional possible explanations?

Determine whether the starting claim is based upon a sample that is both representative and sufficiently large, and ask yourself whether all relevant factors have been taken into account in the analysis of data that leads to a generalization.

Another way to evaluate a premise is to determine whether its source is credible. Ask yourself,

- Are the authors identified?

- What are their backgrounds?

- Was the claim something you found on an undocumented website?

- Did you find it in a popular publication or a scholarly one?

- How complete, how recent, and how relevant are the studies or statistics discussed in the source?

What Is Inductive Argument?

In contrast to a deductive argument, an inductive argument is an argument whose conclusion is supposed to follow from its premises with a high level of probability, which means that although it is possible that the conclusion doesn’t follow from its premises, it is unlikely that this is the case. Here is an example of an inductive argument:

Tweets is a healthy, normally functioning bird and since most healthy, normally functioning birds fly, Tweets most likely flies.

Notice that the conclusion, “Tweets probably flies,” contains the words “most likely.” This is a clear indicator that the argument is supposed to be inductive, not deductive. Here is the argument in standard form:

- Tweets is a healthy, normally functioning bird. (premise)

- Most healthy, normally functioning birds fly. (premise)

- Therefore, Tweets probably flies. (conclusion)

Given the information provided by the premises, the conclusion does seem to be well supported. That is, the premises provide strong reasons for accepting the conclusion. The inductive argument’s conclusion is a strong one, even though we can imagine a scenario in which the premises are true and yet the conclusion is false.

Remember, inductive arguments cannot guarantee the truth of the conclusion, which means they will look like invalid deductive arguments. Indeed, they are. There will be counterexamples for inductive arguments because an inductive argument never promises absolute truth. We measure inductive arguments by degrees of probability and plausibility, not absolute categories like validity and soundness. Validity and soundness do not allow for a sliding scale of degrees. They are absolute conditions: There is no such thing as being partially valid or somewhat sound.

Do not let this difference between deductive and inductive arguments cause you to privilege deductive and revile inductive because inductive arguments cannot guarantee truth. That is an unfair measure, and it is not practical. The truth is that most arguments we create and evaluate in life are inductive arguments. It might be helpful to think of deductive arguments as those created in perfect lab conditions, where all the ideal parameters can be met. Life is much messier than that, and we rarely get ideal conditions. One main reason is that we rarely ever have all the information we need to form an absolutely true conclusion. When new information is discovered, a scientist or historian or psychologist or business executive or a college student should investigate how it affects previous ideas and arguments, knowing that those previous ideas may need to be adjusted based on new information. For example, suppose that we added the following premise to our earlier argument:

Tweets is 6 feet tall and can run 30 mph. (premise)

When we add this premise, the conclusion that Tweets can fly would no longer be likely because any bird that is 6 feet tall and can run 30 mph, is not a kind of bird that can fly. That information leads us to believe that Tweets is an ostrich or emu, which are not kinds of birds that can fly.

The Tests of Inductive Arguments: Reliability and Strength

Inductive arguments can never lead to absolute certainty, which is one reason scholars keep studying and trying to add to knowledge. This does not mean, however, that any inductive argument will be a good one. Inductive arguments must still be evaluated and tested, and the two main tests are reliability and strength.

Test of reliability, much like that of validity for deductive arguments, tests an inductive argument’s reason, its internal logic. In other words, just because an inductive argument cannot guarantee a true conclusion doesn’t mean that it should not be logically constructed. One cannot make just any sort of claim, particularly one that does not have a reliable basis. Reliability, unlike validity, can be measured by degree. More reliable arguments are ones that have a more solid basis in reason. Consider this example:

Ninety-seven percent of BananaTM computers work without any glitches. (premise)

Max has a BananaTM computer. (premise)

Therefore, Max’s computer works without any glitches. (conclusion)

This argument has a high degree of reliability. While it may well be true that Max has one of the three percent of computers that have glitches, it is much more likely, given the initial premise that he does not. If the initial premise changes, however, so does the reliability of the argument:

Thirty-three percent of BananaTM computers work without any glitches.

Max has a BananaTM computer.

Therefore, Max’s computer works without any glitches.

Note how the degree of reliability has gone done dramatically. The argument can now be considered unreliable since the conclusion that Max’s computer will work without glitches is improbable given the premises provided. The conclusion still could be true, but it has tipped toward unlikely.

The second test of inductive arguments is strength. Strength, like reliability, can be measured by degree. Strong arguments must have the following conditions: (1) They must be reliable arguments; (2) they draw upon multiple lines of reasoning as support and/or a collection of data. Indeed, the more the data and the more the reasons for a conclusion, the stronger the argument. Consider the following argument:

Susie has walked by Mack the dog every day for ten days. (premise)

Mack the dog has never bitten Susie. (premise)

Thus, when Susie walks by Mack the dog today, he will not bite her. (conclusion)

This argument is reasonable; we can see that the premises may logically lead to the conclusion. However, the argument is not very strong as Susie has only walked by the dog for ten days. Is that enough data to make the conclusion a likely one? What if we had more data, like so—

Susie has walked by Mack the dog every day for five years.

Mack the dog has never bitten Susie.

Thus, when Susie walks by Mack the dog today, he will not bite her.

This argument, with more data to consider (five years of information instead of just ten days), is much stronger. An argument also gets stronger when reasons are added:

Susie has walked by Mack the dog every day for five years.

Mack the dog has never bitten Susie.

Mack’s owners trained him to be friendly to people. (additional premise)

Mack the dog’s breed is not known for aggression. (additional premise)

Thus, when Susie walks by Mack the dog today, he will not bite her.

This argument is even stronger. Not only does it have more data, but it also has additional reasons for Mack’s gentle nature.

Remember these tests when writing your own essays. You are most likely going to be using inductive arguments, and you should make them as reliable and strong as you can because you can bet your professors will be evaluating your arguments by those criteria as well.

What Are Logical Fallacies, and Why Should You Avoid Them?

Fallacies are errors or tricks of reasoning. A fallacy is an error of reasoning if it occurs accidentally; it is a trick of reasoning if a speaker or writer uses it to deceive or manipulate his audience. Fallacies can be either formal or informal.

Whether a fallacy is an error or a trick, whether it is formal or informal, its use undercuts the validity and soundness of any argument. At the same time, fallacious reasoning can damage the credibility of the speaker or writer and improperly manipulate the emotions of the audience or reader. This is a consideration you must keep in mind as a writer who is trying to maintain credibility (ethos) with the reader. Moreover, being able to recognize logical fallacies in the speech and writing of others can greatly benefit you as both a college student and a participant in civic life. Not only does this awareness increase your ability to think and read critically—and thus not be manipulated or fooled—but it also provides you with a strong basis for counter arguments.

Even more important, using faulty reasoning is unethical and irresponsible. Using logical fallacies can be incredibly tempting. The unfortunate fact is they work. Every day—particularly in politics and advertising—we can see how using faults and tricks of logic effectively persuade people to support certain individuals, groups, and ideas and, conversely, turn them away from others. Furthermore, logical fallacies are easy to use. Instead of doing the often difficult work of carefully supporting an argument with facts, logic, and researched evidence, the lazy debater turns routinely to the easy path of tricky reasoning. Human beings too often favor what is easy and effective, even if morally questionable, over what is ethical, particularly if difficult. However, your college professors’ task is not to teach you how to join the Dark Side. Their job is to teach you how to write, speak, and argue effectively and ethically. To do so, you must recognize and avoid the logical fallacies.

What Are Formal Fallacies?

Most formal fallacies are errors of logic: The conclusion does not really “follow from” (is not supported by) the premises. Either the premises are untrue, or the argument is invalid. Below is an example of an invalid deductive argument:

Premise: All black bears are omnivores.

Premise: All raccoons are omnivores.

Conclusion: All raccoons are black bears.

Bears are a subset of omnivores. Raccoons also are a subset of omnivores. But these two subsets do not overlap, and that fact makes the conclusion illogical. The argument is invalid—that is, the relationship between the two premises does not support the conclusion.

“Raccoons are black bears” is instantaneously recognizable as fallacious and may seem too silly to be worth bothering about. However, that and other forms of poor logic play out on a daily basis, and they have real world consequences. Below is an example of a common fallacious argument:

Premise: All Arabs are Muslims.

Premise: All Iranians are Muslims.

Conclusion: All Iranians are Arabs.

This argument fails on two levels. First, the premises are untrue because, although many Arabs and Iranians are Muslim, not all are. Second, the two ethnic groups (Iranians and Arabs) are sets that do not overlap; nevertheless, the two groups are confounded because they (largely) share one quality in common (being Muslim). One only has to look at comments on the web to realize that the confusion is widespread and that it influences attitudes and opinions about US foreign policy. The logical problems make this both an invalid and an unsound argument.

What Are Informal Fallacies?

Informal fallacies take many forms and are widespread in everyday discourse. Very often they involve bringing irrelevant information into an argument, or they are based on assumptions that, when examined, prove to be incorrect. Formal fallacies are created when the relationship between premises and conclusion does not hold up or when premises are unsound; informal fallacies are more dependent on misuse of language and of evidence.

It is easy to find lists of informal fallacies, but that does not mean that it is always easy to spot them.

How Can You Check for Logical Fallacies?

One way to go about evaluating an argument for fallacies is to return to the concept of the three fundamental appeals: ethos, logos, and pathos. As a quick reminder,

- Ethos is an appeal to ethics, authority, and/or credibility.

- Logos is an appeal to logic.

- Pathos is an appeal to emotion.

Once you have refreshed your memory of the basics, you may begin to understand how ethos, logos, and pathos can be used appropriately to strengthen your argument or inappropriately to manipulate an audience through the use of fallacies. Classifying fallacies as fallacies of ethos, logos, or pathos will help you to understand their nature and to recognize them. Please keep in mind, however, that some fallacies may fit into multiple categories. For more details and examples on errors in the rhetorical appeals, see Chapter 2, “Rhetorical Analysis.”

Fallacies of ethos relate to credibility. These fallacies may unfairly build up the credibility of the author (or his allies) or unfairly attack the credibility of the author’s opponent (or her allies). Some fallacies give an unfair advantage to the claims of the speaker or writer or an unfair disadvantage to his opponent’s claims. These are fallacies of logos. Fallacies of pathos rely excessively upon emotional appeals, attaching positive associations to the author’s argument and negative ones to his opponent’s position.

Key Takeaways: Logic

- Logic—shows how ideas fit together by using reason.

- Formal Logic—a formal and rigorous study of logic, such as in math and philosophy.

- Informal Logic—the application of logic to arguments of all types: in scholarship, in business, and in life. Informal logic is what this part of the chapter covers.

- Deductive Argument—guarantees a true conclusion based on the premises. The tests for deductive arguments are validity and soundness.

- Validity—a way to evaluate a deductive argument; a valid argument is one which, if the premises are true, the conclusion must be true.

- Soundness—the second way to evaluate a deductive argument; a sound argument is one where the argument is valid AND the premises have been shown to be true (via support).

- Inductive Argument—cannot guarantee a true conclusion but can only assert what is most likely to be true based on the premises and the support. The tests for inductive arguments are reliability and strength.

- Reliability—a test of reason for inductive arguments. Inductive arguments must still be reasonable, must still have a reliable basis in logic.

- Strength—another test for inductive arguments. Inductive arguments are stronger when they have more reasons and more data to support them.

- Logical Fallacy—a flaw or trick of logic to be avoided at all costs. Fallacies can be formal or informal. See the Repository of Logical Fallacies below for individual examples.

4. What Are the Different Types of Arguments in Writing?

Throughout this chapter, you have studied the definition of argument, parts of argument, and how to use logic in argument. This section brings all of the previous material together and tackles arguments in writing. Foremost on most students’ minds when taking college composition courses is this question: “How do I write an argument paper?” The answer is not a simple one because, as mentioned previously, arguments come in a variety of packages. This means that written arguments–whether in essay or some other form–also come in many different types.

Arguments of the Rhetorical Modes

Most arguments involve one or more of the rhetorical modes. Once again, rhetoric is the study and application of effective writing techniques. There are a number of standard rhetorical modes of writing—structural and analytical models that can be used effectively to suit different writing situations. The rhetorical modes include, but are not limited to, narrative, description, process analysis, illustration and exemplification, cause and effect, comparison, definition, persuasion, and classification. These modes will be covered in detail in Chapter 5, “Rhetorical Modes.” They are mentioned here, however, to make clear that any and all rhetorical modes can be used to pursue an argument. In fact, most professors will insist upon it.

Tip

Remember that when writing arguments, always be mindful of the point of view you should use. Most academic arguments should be pursued using third person. For more on this issue, see Chapter 4, “The Writing Process.”

Arguments of Persuasion

One of the most common forms of argument is that of persuasion, and often standardized tests, like the SOL, will provide writing prompts for persuasive arguments. On some level, all arguments have a persuasive element because the goal of the argument is to persuade the reader to take the writer’s claim seriously. Many arguments, however, exist primarily to introduce new research and interpretation whereas persuasive arguments expressly operate to change someone’s mind about an issue or a person.

A common type of persuasive essay is an Op-Ed article. Included in the opinion section of a newspaper, these articles are more appropriately called argument essays because most authors strive not only to make explicit claims but also to support their claims, sometimes even with researched evidence. These articles are often well-designed persuasive essays, written to convince readers of the writer’s way of thinking.

In addition to essays, other forms of persuasive writing exist. One common and important example is the job letter, where you must persuade others to believe in your merits as a worker and performer so that you might be hired.

In a persuasive essay, you should be sure to do the following:

- Clearly articulate your claim and the main reasons for it. Avoid forming a thesis based on a negative claim. For example, “The hourly minimum wage is not high enough for the average worker to live on.” This is probably a true statement, but persuasive arguments should make a positive case because a negative is hard to prove. That is, the thesis statement should focus on how the hourly minimum wage is too low or insufficient.

- Anticipate and address counterarguments. Think about your audience and the counterarguments they would mostly likely have. Acknowledging points of view different from your own also has the effect of fostering more credibility between you and the audience. They know from the outset that you are aware of opposing ideas and that you are not afraid to give them space.

- Make sure your support comes in many different forms. Use logical reasoning and the rhetorical appeals, but also strive for concrete examples from your own experience and from society.

- Keep your tone courteous, but avoid being obsequious. In other words, shamelessly appealing to your readers’ vanity will likely ring false. Aim for respectful honesty.

- Avoid the urge to win the argument. On some level, we all want to be right, and we want others to see the error of their ways. More times than not, however, arguments in which both sides try to win end up producing losers all around. The more productive approach is to persuade your audience to consider your claim as a sound one, not simply the right one.

Tip

Because argument writing is designed to convince readers of an idea they may not have known before or a side of an issue they may not agree with, you must think carefully about the attitude you wish to convey as you advance your argument. The overall attitude of a piece of writing is its tone, and it comes from the words you choose (for more on the importance of word choice, see Chapter 10, “Working with Words”) In argument writing, strive for the following:

- Confidence—The reader needs to know that you believe in what you say, so be confident. Avoid hedgy and apologetic language. However, be careful not to cross the line from confidence to overconfidence. Arrogance can rebuff your readers, even if they agree with you.

- Neutrality—While you may advocate for one side or way of thinking, you still must demonstrate that you are being as objective as you can in your analysis and assessment. Avoid loaded terms, buzzwords, and overly emotional language.

- Courtesy and fairness—Particularly when dealing with any counterarguments, you want your tone to reveal that you have given other points of view due consideration. Avoid being smug, snide, or harshly dismissive of other ideas.

Arguments of Evaluation

If you have ever answered a question about your personal take on a book or movie or television show or piece of music, you have given a review. Most times, these reviews are somewhat hasty and based on initial or shallow impressions. However, if you give thought to your review, if you explain more carefully what you liked or didn’t like and why, if you bring in specific examples to back up your points, then you have moved on to an argument of evaluation. Reviews of film, books, music, food, and other aspects of taste and culture represent the most familiar type of argument of evaluation. The main objective of an argument of evaluation is to render a critical judgment on the merits of something.

Another common argument of evaluation is the performance review. If you have ever held a job, you know what it feels like to be on the receiving end of such a review; your timeliness and productivity and attitude are scrutinized to determine if you have been a good worker or need to worry about looking for another job. If you are in any sort of supervisory position, you will be the one writing and delivering those reviews, and your own supervisor will want to know that you have logical justification and evidence for your judgements.

For all types of reviews or evaluation arguments, make sure to plan for the following:

- Declare your overall judgment of the subject under review—good, bad, or somewhere in between. This is your conclusion or thesis.

- Lay out the criteria for your judgment. In other words, your review must be based on logical criteria—i.e., the standards by which you evaluate something. For example, if you are reviewing a film, reasonable criteria would include acting, writing, storytelling, directing, cinematography, music, and special effects. If you are evaluating an employee, that criteria will change and more likely involve punctuality, aspects of job performance, and overall attitude on the job.

- Make sure to evaluate each criteria and provide evidence. Draw your evidence from what you are reviewing, and use as many specific examples as you can. In a movie review in which you think the acting quality was top notch, give examples of a particular style that worked well or lines delivered effectively or emotions realistically conveyed.

- Use concrete language. A review is only an argument if we can reasonably see—from examples and your explanations—how you arrived at your judgment. Vague or circular language (“I liked it because it was just really good!”) will keep your evaluation at the opinion level only, preventing it from being taken seriously as an argument.

- Keep the tone respectful—even if you ultimately did not like the subject of your review. Be as objective as you can when giving your reasons. Insulting language detracts from the seriousness of your analysis and makes your points look like personal attacks.

Roger Ebert (1942-2013), a movie reviewer for the Chicago Sun-Times, was once one of the most famous movie critics in America. His reviews provide excellent examples of the argument of evaluation.

Consider his review (https://tinyurl.com/y82ylaav)of the 2009 film Avatar and note how clearly he declares his judgements, how he makes his reader aware of just what standards he uses for judgement (his criteria), and how he uses a wealth of examples and reasons to back his critiques (although he is careful to avoid spoilers, the review went to print as the movie was coming out).

Sample Writing Assignment

Write a brief review (1 page) of your first job. How would you rate that experience, and what would your rating be based on?

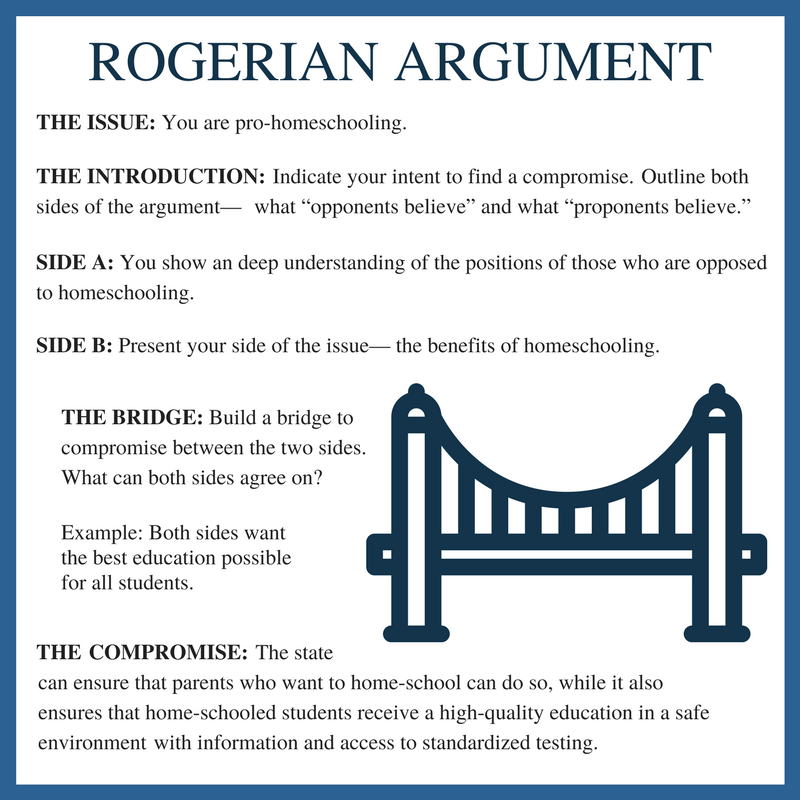

- Declare your overall judgment of your job experience. This is your main claim.