Chapter 12: Part 2 Review

Summary of Part 2

In Part 2, we learned how to identify the connections between ideas as we read. Essentially, we are thinking while we read. We focused on identifying and understanding various patterns that connect ideas within paragraphs and longer texts. Recognizing these patterns enhances comprehension and aids in distinguishing main ideas from supporting details. These chapters covered:

-

List Pattern: Items or ideas presented in a series without a specific order.

-

Chronological Pattern: Events or steps described in the order they occur in time.

-

Comparison Pattern: Highlighting similarities between two or more subjects.

-

Contrast Pattern: Emphasizing differences between subjects.

-

Example Pattern: Providing specific instances to illustrate a point.

These chapters also addressed paragraphs that incorporate multiple patterns and discussed the importance of transition words that signal each pattern. Additionally, the chapters highlighted potential confusion when transitions don’t align with the overall pattern. By mastering these concepts, you can better understand the structure and flow of information, leading to improved reading comprehension.

Part 2 Practice

As you read through this essay, engage your critical thinking skills and look for connections between ideas. After each paragraph, pause and see if you noticed any transitions or clues to the relationship of that paragraph. After you’ve performed an active reading of the text, answer the questions below.

Abraham Maslow was an American psychologist who studied human motivation. His early work looked at the use of dominance to meet one’s needs. He believed that social classes were maintained by the dominance of some members of society over others. To test this belief, he spent time with the Siksika (Blackfoot) nation in Alberta, Canada. However, Maslow did not witness the dominance he expected. Instead, he observed a society that functioned through cooperation. Those who behaved badly were not labeled as criminals. Rather, they could earn their place in the tribe back by simply ceasing their bad behavior. Unlike in European-American communities, parents were not strict disciplinarians with their children, yet children still displayed great respect for their elders.

During his first week with the Siksika, he observed a “Giving Away” ceremony. During the ceremony, the tribe arranged their tipis in a circle. Each member piled their belongings in front of their tipis. Then the needy members of the tribe went around the circle and took what they needed from the piles. Each time, the original owner would tell the story of how they had gotten the possession while the needy member listened respectfully. By the end of the ceremony, the wealthiest in the tribe had given away nearly all of their belongings. Maslow observed, “for the Blackfoot, wealth was not measured by money and property but by generosity. The wealthiest man in their eyes is one who has almost nothing because he has given it all away” (Ravilochan).

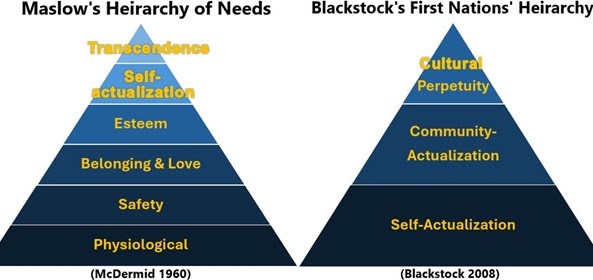

This experience led Maslow to research how humans become self-actualized. In 1943, Maslow published his research on what is now referred to as “Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.” In his published work, he identified five levels of needs: physiological, safety, love and belonging, esteem, and self-actualization. Physiological needs include food and clothing. Safety needs include shelter, safety from harm, and job security. Love and belonging needs include family, friendship, and life partners. Esteem needs include feeling proud of who you are and what you do. Self-actualization needs include being able to be your true self and follow your passions. Maslow identified a sixth need, but due to outside pressures, he chose not to publish it. He called the sixth need “Self-transcendence.” Self- transcendence is the state of having a broader purpose and connection to others.

However, while Maslow saw self-actualization as something people earn after they have met their other needs, the Siksika see it as something you are born with. The expectation is that each member is born with an inherent wisdom, and it is their responsibility to live up to that wisdom. It is for this reason that children are parented so permissively and those who behave badly are allowed to self-correct. Each child brings its own wisdom to the community, so adults are more open to listening to children’s ideas and trusting their choices. Each individual is born with a unique purpose, so it is the community’s responsibility to create an environment in which each individual can reach their full potential.

Many First Nation tribes believe it is the community’s responsibility to meet the basic needs of its members. In his book, Decolonizing Wealth, Edgar Villanueva interviews Dana Arviso, a member of the Navajo tribe. She shared what she had been told by members of a community on the Cheyenne River:

“They told me they don’t have a word for poverty,” she said. The closest thing that they had as an explanation for poverty was ‘to be without family.’” Which is basically unheard of. “They were saying it was a foreign concept to them that someone could be just so isolated and so without any sort of a safety net or a family or a sense of kinship that they would be suffering from poverty” (qtd. in Villanueva).

Dr. Cindy Blackstock, a member of the Gitxsan tribe, created a hierarchy to illustrate the differences between Maslow’s theory and what more accurately depicts the hierarchy of needs in most First Nation cultures. Unlike the European-American worldview, which places individual needs above community needs, First Nations generally prioritize the community. Because the individual is born already self-actualized, it is up to the community to work together to meet the basic needs of each member. That is the true purpose of community, and when a community is able to do that, it reaches Community-actualization. Another difference is the concept of Cultural Perpetuity. First Nation communities see themselves as belonging to an intergenerational system. Blackstock explains:

First Nations often consider their actions in terms of the impacts of the “seven generations.” This means that one’s actions are informed by the experience of the past seven generations and by considering the consequences for the seven generations to follow” (qtd. in Ravilochan).

Teju Ravilochan indicates that in his unpublished work, Maslow’s ideas more closely matched the First Nations’ worldview. For example, Maslow acknowledged the need of the individual to do more than meet their own needs. He quotes Maslow from his unpublished paper, “Critique of Self-Actualization Theory”:

“…self-actualization is not enough. Personal salvation and what is good for the person alone cannot be really understood in isolation. The good of other people must be invoked as well as the good for oneself. It is quite clear that purely inter- psychic individualist psychology without reference to other people and social conditions is not adequate” (qtd. in Ravilochan).

Moreover, Maslow’s writings also indicated that the relationship between human needs is not strictly hierarchical. He writes in his paper:

“We have spoken so far as if this hierarchy were a fixed order but actually it is not nearly as rigid as we may have implied. It is true that most of the people with whom we have worked have seemed to have these basic needs in about the order that has been indicated. However, there have been a number of exceptions” (Maslow).

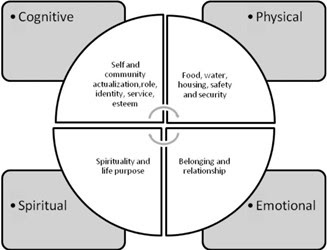

Dr. Blackstock takes this assessment even further. In her article, “The Emergency of the Breath of Life Theory,” she represents these needs as cyclical and interrelated.

Ultimately, while Maslow succeeded in creating a theory of needs that drive Euro-centric cultures, his model fell short of providing the universal theory of motivation he sought to formulate. His observations among the Siksika people revealed a more interconnected, community-driven approach to human well-being, where self-actualization is seen as inherent rather than earned. The First Nations’ worldview, with its focus on community, intergenerational responsibility, and cultural perpetuity, challenges Maslow’s hierarchical structure, emphasizing that individual fulfillment cannot exist in isolation from communal welfare. Maslow’s unpublished work and reflections indicate that he recognized these limitations in his theory. By integrating the values of community-actualization and cultural continuity, we gain a more holistic understanding of human motivation—one that bridges both individual and collective needs.

Works Cited

Blackstock, Cindy. “Revisiting the Breath of Life Theory.” The British Journal of Social Work, Volume 49, Issue 4, June 2019, Pages 854–859,https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcz047

Blackstock, Cindy. “The Emergency of the Breath of Life Theory.” Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics, vol. 8, No. 1, 2001.

Maslow, Abraham. “A Theory of Human Motivation.” Psychological Review, vol. 50, 1943, pp. 370–96, psychclassics.yorku.ca/Maslow/motivation.html.

Ravilochan, Teju. “The Blackfoot Wisdom That Inspired Maslow’s Hierarchy.” Resilience, 18 June 2021,www.resilience.org/stories/2021-06-18/the-blackfoot-wisdom-that-inspired-maslows-hierarchy/.

Practice 12.1

-

In paragraph 1, what did Maslow expect to find when he studied the Siksika people, and what did he actually observe? What is the pattern of this paragraph?

-

Paragraph 2 describes the “Giving Away” ceremony. What is the pattern of this paragraph? How do you know?

-

What is the significance of the “Giving Away” ceremony in the Siksika culture?

-

In paragraph 3, we learn about “Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.” What is the pattern of development in this paragraph?

-

How would you explain the Hierarchy of Needs?

Practice 12.2

-

Why do you think the Siksika believe that self-actualization is something you are born with?

-

What are the benefits of a community-focused approach to meeting people’s needs, as seen in the Siksika culture?

-

How can modern societies learn from the Siksika’s approach to generosity and community support?

-

Why is it important to consider the impact of our actions on future generations, as the First Nations do?

Practice 12.3

Practice 12.4

Practice 12.5

Practice 12.6

Practice 12.7

Practice 12.8

Practice 12.9

Attribution

Strengthening Reading and Comprehension by Audrey Cross and Katherine Sorenson is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International

Media Attributions

- Hierarchy of needs pyramids © Cindy Blackfoot

- Cycle of Interrelated Needs © Cindy Blackstock

(hī-ər-är-kē), n.

A system in which people or things are ranked one above the other based on authority or importance.

/ˌfizēəˈläjək(ə)l/

adjective

relating to the branch of biology that deals with the normal functions of living organisms and their parts.

(in-hĕr′ənt), adj.

Existing in something as a permanent, essential, or characteristic attribute.