16 Chapter 16: Financial Epidemiology

Chapter 16: Financial Epidemiology

Objectives

After completing this module, you should be able to:

Describe the sub-field of financial epidemiology.

Describe the development of measurements in financial epidemiology.

16.1 Introduction

With very few exceptions, most of the world’s population today uses money, and most adults are required to manage money as a fundamental part of life. The management of money and financial resources that an individual or family performs over time within an economic system is called ‘personal finance.’ Despite money’s existence being based on humanity’s collective imagination and the integrated nature of the global economy today (Harari, 2015), the role of personal finance in health has not been systematically and thoroughly explored by epidemiologists. The author thus wishes to hereby refer to the study of how personal finance and associated psychological attributes influence health at the population level as financial epidemiology. This chapter will provide a summary of the central tenets and hypotheses in the field, mostly from the author’s own experience but also including the work of others, as well as remarks on the development of study instruments and research methods.

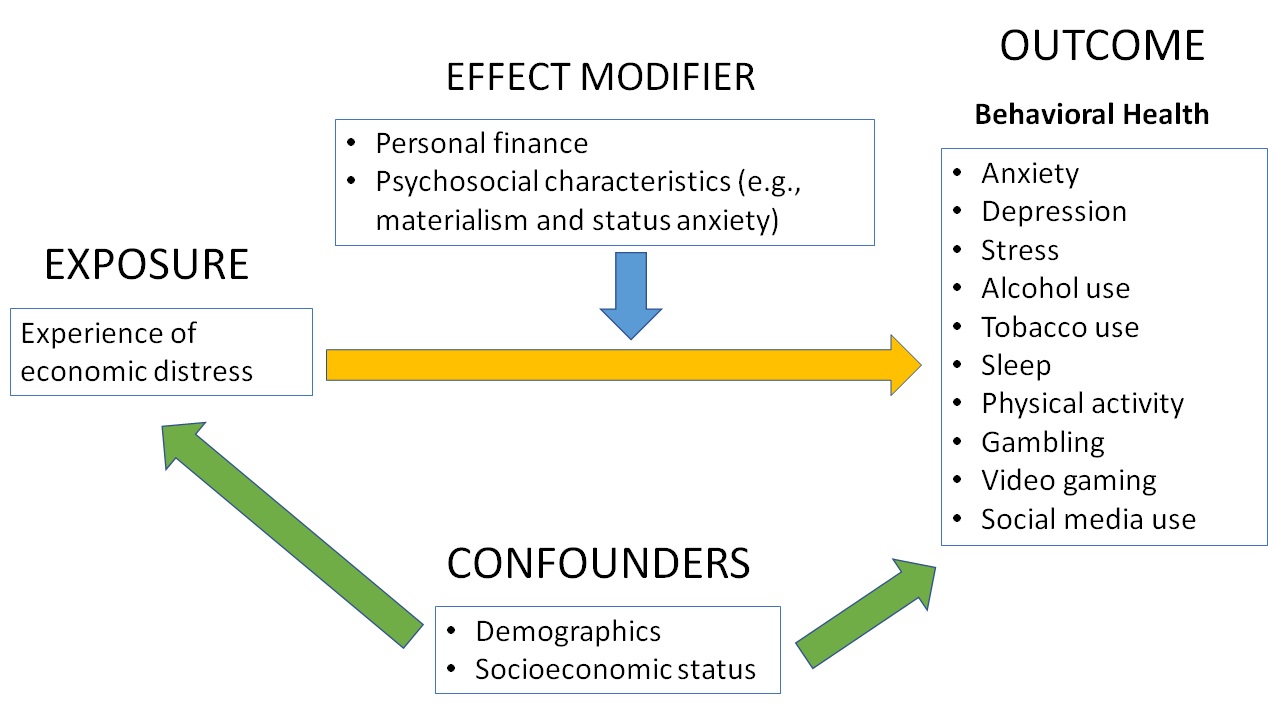

As the subject matter of personal finance encompasses multiple disciplines, including finance and family economics, the role of personal finance in health can be conceptualized based on the family stress model proposed by Pauline Boss (Boss, 2002). The family stress model posits that a given event or situation (including economic distress, e.g., loss of employment or income) can induce stress at varying degrees in a family, but the availability of resources and perception of the event or situation can moderate this induction of stress. To expand on this model, the author hypothesizes that, in addition to stress, economic distress is associated with mental health problems (e.g., depression and anxiety) and behavioral health issues (e.g., substance abuse and addictive behaviors). The author also hypothesizes that personal finance ensures the availability of one of the most versatile resources in the modern economy: money. Thus, the author further hypothesizes that emergency cash reserves function as an effect modifier in the association between the experience of economic distress and behavioral health outcomes, and they tested this hypothesis using data from a survey of the general population of adults in Thailand (Wichaidit et al., 2022).

However, the other effect modifier (referred to as “moderator” by Boss) has not yet been systematically tested: the perception of the event or situation. To define these perceptions, the epidemiologist may need to explore the theoretical frameworks in other disciplines, including psychology, sociology, and philosophy. One possible theory is that human beings constantly compare themselves against others and strive to improve their standing relative to others, i.e., improve their relative social status (Payne, 2017). Relative social status is also found to be associated with stress levels and health outcomes — a tendency that is likely a residual effect of evolutionary traits (Payne, 2017). In modern society, material possessions are used as a proxy of success and (effectively) as a measure of one’s social status relative to others, which indirectly determines social interactions. This concept is known as materialism. In materialistic societies, one needs to maintain an image of material success and comfort constantly in order to be perceived by others as having a social status worthy of decent interactions. This constant concern regarding one’s social status within such a society can be referred to as “status anxiety” (De Botton, 2004; Melita et al., 2021). Economic distress or hardship threatens this very ability to maintain materials necessary to convey an image of success and social status, and anxiety and other behavioral health issues may ensue. However, personal outlooks regarding materialism may enable one to develop resilience and lower the probability of behavioral health issues when facing economic distress. The author hypothesizes that perception of meritocracy, materialism, and status anxiety also function as effect modifiers in the association between economic distress and behavioral health outcomes in addition to personal finance. A summary of the theoretical concepts in financial epidemiology can be found in Figure 16.1.1

Figure 16.1.1 Conceptual framework for the role of personal finance in behavioral health epidemiology

16.2 Measurement in Financial Epidemiology

Owing to the nascent nature of the sub-field, the author generally uses a cross-sectional study design to develop and validate the study instrument and develop hypotheses and theoretical frameworks. The study questionnaire can be based on existing tools in routine surveys of behavioral health in the general population (Paileeklee et al., 2016; Wichaidit et al., 2021), which allows us to measure the outcomes. The measurement of exposure (economic distress) can also be based on previous studies (Richardson et al., 2017; Siahpush & Carlin, 2006).

The more challenging measurement is the measurement of variables not previously done in epidemiology. The measurement of personal finance can be adapted from existing tools in economics (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2019), with adaptations to the local context. For example, in the measurement of the availability of emergency cash reserves, an investigator may need to adjust the monetary amount by the purchasing power parity of the study setting and further reduce the subjectivity of the definition of an emergency by specifying one week as a timeframe to define an emergency expense (Wichaidit et al., 2022) (Box 16.2.1).

Box 16.2.1 Development of the question to measure the availability of emergency cash reserves in Thailand

|

Original measurement question from the US Federal Reserve Board’s Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking (SHED) 2018 EF3. Suppose that you have an emergency expense that costs $400. Based on your current financial situation, how would you pay for this expense? If you would use more than one method to cover this expense, please select all that apply. a. Put it all on my credit card and pay it off in full at the next statement b. Put it on my credit card and pay it off over time c. With the money currently in my checking/savings account or with cash d. Using money from a bank loan or line of credit e. By borrowing from a friend or family member f. Using a payday loan, deposit advance, or overdraft g. By selling something h. I wouldn’t be able to pay for the expense right now i. Other (please specify): [text box] The translation of the question adapted for a nationally representative survey in Thailand with measurement of behavioral health outcomes (Wichaidit et al., 2022): Q11. Suppose that you have an emergency expense that costs 5,000 Bahts. How would you find money to pay for this expense within a week? (No prompting, wait for an answer, more than one answer allowed) [ ] 1) Put it on my credit card and pay it off in full at the next statement [ ] 2) Put it on my credit card and pay it off over time [ ] 3) With the money in savings account, cash, or other liquid assets (e.g., converting mutual funds to cash) [ ] 4) Using money from a bank loan or line of credit [ ] 5) By borrowing from a friend or family member [ ] 6) Using a payday loan, deposit advance, or overdraft [ ] 7) Selling my personal items [ ] 8) Pawning my assets [ ] 9) I wouldn’t be able to pay for the expense right now [ ] 10) Other (please specify) [ ] 99) Refuse to answer |

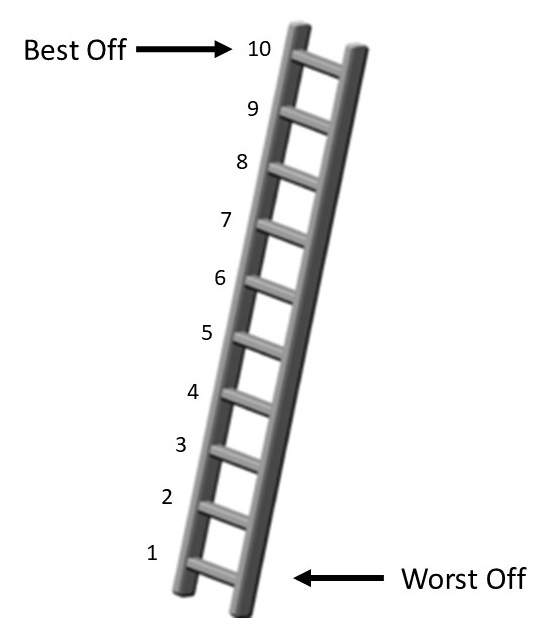

In addition, questions regarding the psychosocial characteristics may be less readily available from existing studies, and the epidemiologist may need to adapt the tools used in previous studies to measure constructs like status anxiety (Melita et al., 2021) and materialism (Chen et al., 2014; Richins, 2004). Investigators can consider tools widely used in previous studies, such as the MacArthur subjective social status scale (MacArthur et al., 2020); question the construct definition; and expand on existing measurement methods, like adding more reference groups, and exploring these methods’ associations with behavioral health outcomes accordingly (Box 16.2.2).

Box 16.2.2 Use of the MacArthur scale of subjective social status with multiple reference groups

|

Imagine that the ladder below represents a group of people At the top rung (rung no. 10) are those who are most comfortable within the group; those with the most money, the best education, and the best jobs At the bottom rung (rung no. 1) are those who experience the most hardship; those with the last money, the worst education, and the worst jobs or are unemployed

|

||||||||||||

Investigators can also define the construct based on books and other grey literature (De Botton, 2004; Payne, 2017) and develop additional measurement questions.

16.3 Conclusion

Financial epidemiology is a sub-field of epidemiology that investigates how personal finance and associated psychological attributes influence health at the population level. An existing theoretical framework posits that personal finance supposedly functions as an effect modifier in the association between economic distress and behavioral health issues; however, other psychosocial factors that are found in the modern economy, like meritocracy and materialism, can also function as additional effect modifiers.

All of the hypotheses presented in this chapter are yet to be tested, and readers are encouraged to either test and disprove these hypotheses or develop additional ones of their own to advance our understanding of how personal finance and the perception of the modern economic system affect health. The findings of these studies can also offer information to stakeholders in other fields, such as economics and sociology, as the constructs measured are of interest to other disciplines.

References

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. (2019). Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2018. U.S. Federal Reserves. https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/2018-report-economic-well-being-us-households-201905.pdf

Boss, P. (2002). Family Stress Management: A Contextual Approach (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452233895

Chen, Y., Yao, M., & Yan, W. (2014). Materialism and well-being among Chinese college students: The mediating role of basic psychological need satisfaction. Journal of Health Psychology, 19(10), https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105313488973

De Botton, A. (2004). Status Anxiety. Pantheon Books.

Harari, Y. N. (2015). Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. Harper.

MacArthur, G. J., Hickman, M., & Campbell, R. (2020). Qualitative exploration of the intersection between social influences and cultural norms in relation to the development of alcohol use behaviour during adolescence. BMJ Open, 10(3), PubMed. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030556

Melita, D., Willis, G. B., & Rodríguez-Bailón, R. (2021). Economic Inequality Increases Status Anxiety Through Perceived Contextual Competitiveness. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 637365–637365. PubMed. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.637365

Paileeklee, S., Dithisawatwet, S., Seeoppalat, N., Thaikla, K., Jaroenratana, S., Chindet, A., & Tantirangsee, N. (2016). A surveillance of alcohol, tobacco, substance use and health-risk behaviors among high school students in Thailand (p. 81). Thai Health Promotion Foundation (ThaiHealth).

Payne, K. (2017). The broken ladder: How inequality affects the way we think, live, and die. Viking.

Richardson, T., Elliott, P., Roberts, R., & Jansen, M. (2017). A Longitudinal Study of Financial Difficulties and Mental Health in a National Sample of British Undergraduate Students. Community Mental Health Journal, 53(3), PubMed. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-016-0052-0

Richins, M. L. (2004). The Material Values Scale: Measurement Properties and Development of a Short Form. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(1), JSTOR. https://doi.org/10.1086/383436

Siahpush, M., & Carlin, J. B. (2006). Financial stress, smoking cessation and relapse: Results from a prospective study of an Australian national sample. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 101(1), https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01292.x

Wichaidit, W., Prommanee, C., Choocham, S., Chotipanvithayakul, R., & Assanangkornchai, S. (2022). Modification of the association between experience of economic distress during the COVID-19 pandemic and behavioral health outcomes by availability of emergency cash reserves: Findings from a nationally-representative survey in Thailand. PeerJ, 10, e13307. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.13307

Wichaidit, W., Sittisombut, M., Assanangkornchai, S., & Vichitkunakorn, P. (2021). Self-reported drinking behaviors and observed violation of state-mandated social restriction and alcohol control measures during the COVID-19 pandemic: Findings from nationally-representative surveys in Thailand. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 221, 108607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108607