18 Prior Knowledge: Working With What Students Already Know

Students enter the classroom with diverse prior knowledge, skills, and beliefs, which shape how they engage with new material. Understanding these pre-existing factors allows instructors to tailor instruction, reinforcing foundational concepts where needed and advancing when students demonstrate proficiency. This chapter explores methods for assessing prior knowledge, including performance-based tasks, self-assessments, and classroom assessment techniques (CATs), to identify strengths and gaps. Strategies such as concept maps, minute papers, and problem-solving exercises help instructors adjust their teaching while empowering students to recognize and address their own learning needs. By integrating these approaches, educators can create more effective, responsive, and student-centered learning environments that build on existing knowledge for deeper engagement and retention.

When students enter the classroom, they bring with them a diverse array of prior knowledge, skills, beliefs, and attitudes. These pre-existing factors shape how students pay attention, interpret new information, and organize it mentally. The way they process and integrate new material directly influences their ability to remember, apply, and build upon that knowledge. Since learning is rooted in what students already know, assessing their prior knowledge is essential for crafting instructional activities that build on their strengths while addressing areas of weakness.

By gauging what students know and can do before they begin a new topic or course, instructors can tailor their teaching strategies. If most students share similar gaps or misconceptions in a critical area, instructors might choose to revisit or reinforce that material, offer supplementary sessions, or provide resources for independent study. Conversely, if students demonstrate proficiency in an area, instructors can adjust by moving on to more complex topics or reallocating time to focus on other skills that students still need to develop.

Assessing prior knowledge not only helps instructors design more effective lessons, but it also empowers students to focus their efforts productively. For example, if a student lacks foundational knowledge, they can be encouraged to take prerequisite courses or seek additional resources to catch up, ensuring their success as they progress through the material.

Methods for Assessing Prior Knowledge and Skills

There are various ways to assess students’ pre-existing knowledge and skills, ranging from direct measures like tests and portfolios to more indirect methods like self-assessments. Here are a few effective approaches:

Performance-Based Prior Knowledge Assessments

The most reliable way to assess students’ prior knowledge is to assign a task (e.g., quiz, paper) that gauges their relevant background knowledge.

These assessments are for diagnostic purposes only, and they should not be graded. They can help you gain an overview of students’ preparedness, identify areas of weakness, and adjust the pace of the course.

To create a performance-based prior knowledge assessment, you should begin by identifying the background knowledge and skills students will need to succeed in your class. Your assessment can include tasks or questions that test students’ capabilities in these areas.

Prior Knowledge Self-Assessments

Prior knowledge self-assessments ask students to reflect and comment on their level of knowledge and skill across a range of items. Questions can focus on knowledge, skills, or experiences that:

- you assume students have acquired and are prerequisites to your course

- you believe are valuable but not essential to the course

- you plan to address in the course

The feedback from this assessment can help you calibrate your course appropriately or direct students to supplemental materials that can help them address weaknesses in their existing skills or knowledge.

The advantage of a self-assessment is that it is relatively easy to construct and score. The potential disadvantage of this method is that students may not be able to accurately assess their abilities. However, accuracy improves when the response options clearly differentiate both types and levels of knowledge.

Writing Appropriate Questions for Self-Assessments

Writing appropriate questions for prior knowledge self-assessments can seem daunting at first. Identifying specific terms, concepts, or applications of skills to ask about will help you write effective questions.

Examples of questions with possible closed responses:

How familiar are you with “Karnaugh maps”?

- I have never heard of them or I have heard of them but don’t know what they are.

- I have some idea what they are, but don’t know when or how to use them.

- I have a clear idea what they are, but haven’t used them.

- I can explain what they are and what they do, and I have used them.

Have you designed or built a digital logic circuit?

- I have neither designed nor built one.

- I have designed one, but not built one.

- I have built one, but not designed one.

- I have both designed and built one.

How familiar are you with a “t-test”?

- I have never heard of it.

- I have heard of it, but don’t know what it is.

- I have some idea of what it is, but it’s not very clear.

- I know what it is and could explain what it’s used for.

- I know what it is and when to use it, and I could use it to analyze data.

How familiar are you with Photoshop?

- I have never used it or I tried using it but couldn’t do anything with it.

- I can do simple edits using preset options to manipulate single images (e.g., standard color, orientation and size manipulations).

- I can manipulate multiple images using preset editing features to create desired effects.

- I can easily use precision editing tools to manipulate multiple images for professional quality output.

Using Classroom Assessment Techniques

Classroom Assessment Techniques (CATs) are a set of specific activities that instructors can use to quickly gauge students’ comprehension. They are generally used to assess students’ understanding of material in the current course, but with minor modifications they can also be used to gauge students’ knowledge coming into a course or program.

CATs are meant to provide immediate feedback about the entire class’s level of understanding, not individual students’. The instructor can use this feedback to inform instruction, such as speeding up or slowing the pace of a lecture or explicitly addressing areas of confusion.

Asking Appropriate Questions in CATs

Examples of appropriate questions you can ask in the CAT format:

- How familiar are students with important names, events, and places in history that they will need to know as background in order to understand the lectures and readings (e.g., in anthropology, literature, political science)?

- How are students applying knowledge and skills learned in this class to their own lives (e.g., psychology, sociology)?

- To what extent are students aware of the steps they go through in solving problems and how well can they explain their problem-solving steps (e.g., mathematics, physics, chemistry, engineering)?

- How and how well are students using a learning approach that is new to them (e.g., cooperative groups) to master the concepts and principles in this course?

Using Specific Types of CATs

Minute Paper

Pose one to two questions in which students identify the most significant things they have learned from a given lecture, discussion, or assignment. Give students one to two minutes to write a response on an index card or paper. Collect their responses and look them over quickly. Their answers can help you to determine if they are successfully identifying what you view as most important.

Muddiest Point

This is similar to the Minute Paper but focuses on areas of confusion. Ask your students, “What was the muddiest point in… (today’s lecture, the reading, the homework)?” Give them one to two minutes to write and collect their responses.

Problem Recognition Tasks

Identify a set of problems that can be solved most effectively by only one of a few methods that you are teaching in the class. Ask students to identify by name which methods best fit which problems without actually solving the problems. This task works best when only one method can be used for each problem.

Documented Problem Solutions

Choose one to three problems and ask students to write down all of the steps they would take in solving them with an explanation of each step. Consider using this method as an assessment of problem-solving skills at the beginning of the course or as a regular part of the assigned homework.

Directed Paraphrasing

Select an important theory, concept, or argument that students have studied in some depth and identify a real audience to whom your students should be able to explain this material in their own words (e.g., a grants review board, a city council member, a vice president making a related decision). Provide guidelines about the length and purpose of the paraphrased explanation.

Applications Cards

Identify a concept or principle your students are studying and ask students to come up with one to three applications of the principle from everyday experience, current news events, or their knowledge of particular organizations or systems discussed in the course.

Student-Generated Test Questions

A week or two prior to an exam, begin to write general guidelines about the kinds of questions you plan to ask on the exam. Share those guidelines with your students and ask them to write and answer one to two questions like those they expect to see on the exam.

Classroom Opinion Polls

When you believe that your students may have pre-existing opinions about course-related issues, construct a very short two- to four-item questionnaire to help uncover students’ opinions.

Creating and Implementing CATs

You can create your own CATs to meet the specific needs of your course and students. Below are some strategies that you can use to do this.

- Identify a specific “assessable” question where the students’ responses will influence your teaching and provide feedback to aid their learning.

- Complete the assessment task yourself (or ask a colleague to do it) to be sure that it is doable in the time you will allot for it.

- Plan how you will analyze students’ responses, such as grouping them into the categories “good understanding,” “some misunderstanding,” or “significant misunderstanding.”

- After using a CAT, communicate the results to the students so that they know you learned from the assessment and so that they can identify specific difficulties of their own.

Using Concept Maps

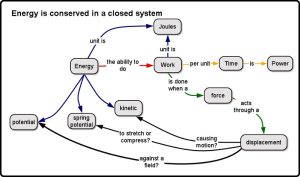

Concept maps are a graphic representation of students’ knowledge. Having students create concept maps can provide you with insights into how they organize and represent knowledge. This can be a useful strategy for assessing both the knowledge students have coming into a program or course and their developing knowledge of course material.

Concept maps include concepts, usually enclosed in circles or boxes, and relationships between concepts, indicated by a connecting line. Words on the line are linking words and specify the relationship between concepts.

Designing a concept map exercise

To structure a concept map exercise for students, follow these three steps:

- Create a focus question that clearly specifies the issue that the concept map should address, such as “What are the potential effects of cap-and-trade policies?” or “What is materials science?”

- Tell students (individually or in groups) to begin by generating a list of relevant concepts and organizing them before constructing a preliminary map.

- Give students the opportunity to revise. Concept maps evolve as they become more detailed and may require rethinking and reconfiguring.

Encourage students to create maps that:

- Employ a hierarchical structure that distinguishes concepts and facts at different levels of specificity

- Draw multiple connections, or cross-links, that illustrate how ideas in different domains are related

- Include specific examples of events and objects that clarify the meaning of a given concept

Using concept maps throughout the semester

Concept maps can be used at different points throughout the semester to gauge students’ knowledge. Here are some ideas:

- Ask students to create a concept map at the beginning of the semester to assess the knowledge they have coming into a course. This can give you a quick window into the knowledge, assumptions, and misconceptions they bring with them and can help you pitch the course appropriately.

- Assign the same concept map activity several times over the course of the semester. Seeing how the concept maps grow and develop greater nuance and complexity over time helps students (and the instructor) see what they are learning.

- Create a fill-in-the-blank concept map in which some circles are blank or some lines are unlabeled. Give the map to students to complete.

Using Concept Tests

Concept tests (or ConcepTests) are short, informal, targeted tests that are administered during class to help instructors gauge whether students understand key concepts. They can be used both to assess students’ prior knowledge (coming into a course or unit) or their understanding of content in the current course.

Usually these tests consist of one to five multiple-choice questions. Students are asked to select the best answer and submit it by raising their hands, holding up a color card associated with a response option, or other polling tool such as Microsoft Forms.

The primary purpose of concept tests is to get a snapshot of the current understanding of the class, not of an individual student. As a result, concept tests are usually ungraded or very low-stakes. They are most valuable in large classes where it is difficult to assess student understanding in real time.

Creating a concept test

Creating a good concept test can be time-consuming, so you might want to see if question repositories or fully developed concept tests already exist in your field.

If you create your own, you need to begin with a clear understanding of the knowledge and skills that you want your students to acquire. The questions should probe a student’s comprehension or application of a concept rather than factual recall. Concept test questions often describe a problem, event, or situation.

Examples of appropriate types of questions include:

- asking students to predict the outcome of an event (e.g., What would happen in this experiment? How would changing one variable affect others?)

- asking students to apply rules or principles to new situations (e.g., Which concept is relevant here? How would you apply it?)

- asking students to solve a problem using a known equation or select a procedure to complete a new task (e.g., What procedure would be appropriate to solve this problem?)

The following question stems are used frequently in concept test questions:

- Which of the following best describes…

- Which is the best method for…

- If the value of X was changed to…

- Which of the following is the best explanation for…

- Which of the following is another example of…

- What is the major problem with…

- What would happen if…

When possible, incorrect answers (“distractors”) should be designed to reveal common errors or misconceptions.

- Example 1: Mechanics (pdf)

This link contains sample items from the Mechanics Baseline Test (Hestenes & Wells, 1992). - Example 2: Statics (pdf)

This link contains sample items from a Statics Inventory developed by Paul Steif, Carnegie Mellon.

Implementing concept tests

Concept tests can be used in a number of different ways. Some instructors use them at the beginning of class to gauge students’ understanding of readings or homework. Some use them intermittently in class to test students’ comprehension. Based on how well students perform, the instructor may decide to move on in the lecture or pause to review a difficult concept.

Another method is to give students the chance to respond to a question individually, then put them in pairs or small groups to compare and discuss their answers. After a short period of time, the students vote again for the answer they think is correct. This gives students the opportunity to articulate their reasoning for a particular answer.

This site contains strategies for implementing ConcepTests that are drawn from STEM fields but are broadly adaptable: https://serc.carleton.edu/sp/library/conceptests/index.html

Sources and Attribution

Primary Source

This section is adapted from:

- Eberly Center for Teaching Excellence & Educational Innovation (n.d.). Assessing Prior Knowledge. Carnegie Mellon University.

- Available at: Eberly Center Website

References

- Angelo, Thomas A., & Cross, K. Patricia. (1993). Classroom Assessment Techniques: A Handbook for College Teachers. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Use of AI in Section Development

This section was developed using a combination of existing research, expert-informed strategies, and AI-assisted drafting. ChatGPT (OpenAI) was used to:

- Synthesize key concepts related to prior knowledge assessment and instructional design into a clear and accessible framework for instructors.

- Refine explanations and practical applications while maintaining alignment with research-based teaching practices.

- Ensure readability and coherence to make the material both theoretically sound and practically useful.

While AI-assisted drafting provided a structured foundation, all final content was reviewed, revised, and contextualized to ensure accuracy, alignment with research, and pedagogical effectiveness. This section remains grounded in scholarly and institutional best practices and respects Creative Commons licensing where applicable.

Media Attributions

- 4422270366_58a2fe0549_c © coach_robbo is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license