22 Understanding by Design (UbD) and the Backward Design Framework

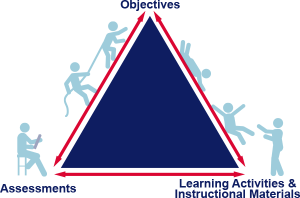

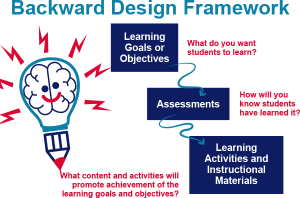

Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe’s Understanding by Design introduces backward design as a structured approach to course planning that centers on intended learning outcomes. Traditional or “forward” course design typically starts with learning activities, builds assessments around them, and then attempts to connect back to learning goals. In contrast, backward design reverses this process by first clarifying the learning goals — the core knowledge and skills students should acquire by the end of the course. Once these goals are established, the next step is to define assessments that will accurately measure students’ progress toward these objectives. Only after these are defined does the instructor design learning activities to support the goals. This intentional approach helps create coherence in course structure and aligns all components with clear educational outcomes.

Benefits of Backward Design

Backward design places a strong focus on student learning and understanding over the delivery of content. By setting clear goals upfront, instructors can shape their course content, assessments, and activities around these objectives, enhancing the purpose and transparency of each course component. This approach also minimizes “filler” activities by ensuring that every task directly contributes to the learning goals. With this clarity, students have a clearer sense of purpose behind activities and are better able to engage with meaningful learning experiences.

This guide will explore backward design’s benefits, detail its three stages, and provide a practical template to help instructors incorporate this approach into their planning. As Wiggins and McTighe note, “Our lessons, units, and courses should be logically inferred from the results sought… the best designs derive backward from the learnings sought.”

The Three Stages of Backward Design

Effective course design begins with a shift in focus toward the specific learning outcomes we want students to achieve. Rather than starting with teaching activities, backward design begins by identifying desired results, then determining how students will demonstrate understanding, and finally planning the instruction that will support these outcomes.

Stage One: Identify Desired Results

Stage Two: Determine Acceptable Evidence

Stage Three: Plan Learning Experience and Instruction

Stage One – Identify Desired Results

The first step in backward design is to clarify what students should know, understand, and be able to do by the end of your course, lesson, or module. This stage involves focusing on big ideas, crafting essential questions, and defining learning objectives to guide the learning process.

Identify the Big Ideas

Start by identifying the big ideas that will anchor your course. These are the core concepts, principles, theories, or processes you hope students will remember years after completing your class. Big ideas serve as:

- Foundational Concepts: Core principles that provide a focal point for prioritizing content.

- Organizers: Tools for connecting discrete facts and skills to a broader intellectual framework.

- Transferable Knowledge: Ideas that students can apply to other topics, contexts, or real-world problems.

Big ideas may include themes, debates, paradoxes, or processes that are not immediately obvious to students and require intentional “uncovering” through instruction and activities.

For Example

- A biology course might center on the big idea of “interdependence in ecosystems.”

- A history course might emphasize “the role of power and perspective in shaping historical narratives.”

These overarching goals are often expressed in broad terms (e.g., “understand,” “value,” or “appreciate”) and may not lend themselves directly to measurement. However, they provide a guiding framework for what you want students to achieve.

Transform Big Ideas Into Essential Questions

Once you’ve identified the big ideas, translate them into essential questions. These questions drive inquiry and stimulate student thinking. Essential questions:

- Encourage debate and reflection, avoiding simple right-or-wrong answers.

- Focus on significant issues, problems, or debates within a discipline.

- Are designed to provoke thought and inspire further questions, often crossing disciplinary boundaries.

For Example

- In a philosophy course, an essential question might be: “What is the role of morality in shaping societal laws?”

- In a business course, you could ask: “What makes a business strategy sustainable in today’s economy?”

Essential questions help students rethink big ideas, challenge assumptions, and engage with content in meaningful ways.

Craft Learning Objectives

With your big ideas and essential questions in mind, develop learning objectives that are specific, measurable, and actionable. These objectives articulate what students should achieve and help structure your course design.

SMART Learning Objectives are:

- Specific: Clearly define what students will achieve.

- Measurable: Include criteria for assessing progress.

- Attainable: Ensure objectives are realistic within the course’s scope.

- Relevant: Align objectives with the course goals.

- Timely: Include a timeframe for completion.

A strong learning objective includes:

- The subject (students),

- An action verb (what they will do),

- A criterion (how well they must do it),

- A context or condition, and

- A timeframe.

Examples

Science

Objective: By the end of the unit, students will accurately label the parts of a eukaryotic cell on a diagram and describe their functions in a short written response.

-

Specific: Identifies what students will label and describe

-

Measurable: Accuracy in labeling and clarity of description can be assessed

-

Attainable: Realistic for one unit of instruction

-

Relevant: Tied to understanding cell biology fundamentals

-

Timely: Bound to “by the end of the unit”

Communication

Objective: During the final presentation, students will demonstrate effective verbal and non-verbal communication strategies in a 5-minute persuasive speech.

-

Specific: Focus on presentation skills and communication strategies

-

Measurable: Observable behaviors during the speech

-

Attainable: Appropriate for students preparing over a term

-

Relevant: Linked to communication course goals

-

Timely: Tied to the final presentation event

Art History

Objective: By mid-semester, students will compare and contrast the stylistic features of Baroque and Renaissance art in a 500-word discussion post, citing at least two examples.

-

Specific: Defines the artistic periods and the task

-

Measurable: Word count, citation requirement, and quality of comparison

-

Attainable: Manageable for a mid-semester assignment

-

Relevant: Matches course content focus

-

Timely: Due “by mid-semester”

Using tools like Bloom’s Taxonomy or Fink’s Taxonomy of Significant Learning can guide the selection of appropriate action verbs and competencies, ensuring that objectives reflect both academic and humanistic dimensions.

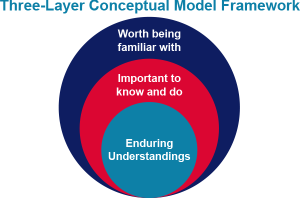

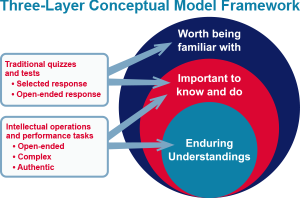

Prioritize Content

Once your learning objectives are clear, prioritize the course content to focus on what matters most. Wiggins and McTighe suggest a three-layer framework to help refine your choices:

- Outer Circle: Content students should be familiar with (e.g., readings, videos, or discussions that provide context or enrichment).

- Middle Circle: Important knowledge and skills (e.g., key facts, concepts, processes, or methods students need to know).

- Inner Circle: Enduring understandings—the core ideas or principles students should retain long after they’ve forgotten specific details.

Ask yourself:

- What knowledge is foundational for students’ success in this course and beyond?

- Which skills will they need to apply in real-world scenarios?

- What core concepts will they remember years later?

By organizing content around these priorities, you ensure that students focus on what is most valuable and transferable.

Guiding Questions for Identifying Desired Results

- What should students hear, read, view, or explore?

- What knowledge and skills should students acquire?

- What big ideas and enduring understandings should students retain?

By thoughtfully addressing these questions, you can design a course that aligns learning activities and assessments with meaningful goals, ensuring students gain lasting knowledge and skills.

Stage Two – Determine Acceptable Evidence

The second stage of backward design involves creating assessments that provide evidence of student learning and progress toward achieving the learning objectives. Effective assessments are aligned with course goals, encourage meaningful engagement, and offer insights into students’ understanding and skill development.

Types of Assessments

Assessment refers to the variety of methods instructors use to evaluate, measure, and document students’ academic readiness, progress, and skill acquisition. There are two primary categories of assessments: summative and formative. Both play vital roles in supporting learning when thoughtfully integrated into course design.

Summative Assessments: Evaluating Learning Summative assessments measure how well students have achieved course objectives by the end of a learning period. These are often high-stakes assessments that contribute significantly to final grades.

Characteristics:

- Purpose: To evaluate overall learning, assess proficiency, and certify achievement for professional credentials or program entry.

- Grading: Typically graded, with clear correct and incorrect responses.

- Timing: Occurs periodically, usually after learning activities are completed.

- Feedback: Often delayed and primarily communicated through grades.

- Stakes: High stakes, with limited opportunities for revision or improvement.

Examples:

- Exams

- Final portfolios

- Presentations

- Research papers

Formative Assessments: Supporting Learning Formative assessments focus on learning in progress. These assessments provide ongoing opportunities for students to practice, reflect, and integrate new knowledge while offering instructors insights into students’ development.

Characteristics:

- Purpose: To guide learning, enhance metacognitive skills, and scaffold the path toward mastery.

- Grading: Sometimes graded, often as participation or completion points.

- Timing: Frequent and ongoing throughout the course.

- Feedback: Timely and actionable, fostering repeated practice and reflection.

- Stakes: Low stakes, with multiple opportunities for improvement.

Examples:

- Homework assignments

- Group problem-solving exercises

- Polling questions or classroom clickers

- One-minute papers or reflections

- Drafts of written or creative work

Matching Assessment Types to Learning Goals

Wiggins and McTighe suggest aligning assessment formats with the type of understanding students need to demonstrate.

For Example:

- When assessing basic facts and skills, traditional tools like quizzes or multiple-choice exams may suffice.

- For assessing enduring understanding, more complex and authentic assessments are appropriate, such as case studies, projects, or portfolios.

By aligning assessments with the goals of the course, instructors ensure that the evidence they gather reflects students’ ability to apply and transfer their learning.

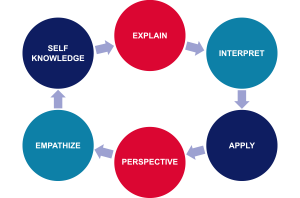

Six Facets of Understanding

To design effective assessments, consider the Six Facets of Understanding, which highlight how students demonstrate true understanding. These facets can guide the creation of authentic and varied assessment strategies.

Students demonstrate understanding when they can:

- Explain: Put concepts into their own words, justify answers, and teach others.

- Interpret: Make sense of data, text, or experiences through analogies, models, or narratives.

- Apply: Use their knowledge in diverse, real-world contexts.

- Demonstrate Perspective: See the big picture and appreciate differing viewpoints.

- Empathize: Value perspectives or ideas that may initially seem unfamiliar or implausible.

- Exhibit Self-Knowledge: Reflect on their own thinking, recognize gaps in their understanding, and consider how their perspectives influence their learning.

For Example

- In a science course, students might demonstrate their ability to apply knowledge by designing an experiment, while in a literature course, they might interpret a novel by creating an original analysis using a specific theoretical lens.

Guiding Questions for Developing Assessments

To ensure assessments align with course objectives, consider these questions:

- How will I know if students have achieved the desired learning outcomes?

- What evidence will demonstrate students’ understanding and proficiency?

- Do the assessments align with and address the course’s learning objectives?

- Are the assessments designed to measure both foundational knowledge and enduring understanding?

By thoughtfully designing assessments that balance summative and formative approaches, instructors create opportunities for students to demonstrate growth, build confidence, and engage deeply with the course material. Authentic assessments aligned with meaningful objectives also support transferable learning, preparing students for challenges beyond the classroom.

Stage Three: Plan Learning Experiences and Instruction

The next step is to design instructional activities and materials that actively engage students and support their achievement of course objectives. This stage involves determining lesson structures, selecting readings, choosing instructional methods, and planning interactive activities—all while keeping student learning at the center of the process.

From Passive to Active Learning

Traditional classroom instruction has often focused on delivering content through lectures and discussions, assuming that students passively absorb information from authoritative sources. However, decades of research demonstrate that active learning—where students interact with, apply, and reflect on knowledge—leads to deeper understanding and greater retention. (See the Active Learning chapter in this guide for more strategies.)

Backward design encourages instructors to move beyond passive information delivery and instead create student-centered learning experiences that promote engagement, critical thinking, and application.

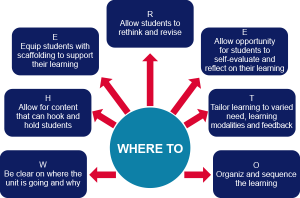

Designing Learning Activities: The WHERETO Framework

One useful framework for structuring learning experiences is WHERETO. This six-part checklist ensures that learning activities are purposeful, engaging, and structured for deep understanding:

- W (Where & Why) – How will you clarify for students where they are headed, why the learning is relevant, and how they will be assessed?

- H (Hook) – How will you capture and sustain students’ interest with engaging, thought-provoking experiences?

- E (Experience & Equip) – What experiences will help students deepen their understanding and develop the skills they need to succeed?

- R (Reflect & Rethink) – How will you encourage students to reflect, revisit, revise, and rethink their ideas?

- E (Express & Evaluate) – How will students demonstrate their understanding and engage in meaningful self-evaluation?

- T (Tailor) – How will you differentiate instruction to support diverse learners, addressing individual strengths and needs?

- O (Organize for Understanding) – How will you sequence activities to scaffold learning, guiding students from structured, teacher-supported activities to independent, conceptual thinking?

Guiding Questions for Developing Learning Activities

As you design learning activities, consider the following:

- What prior knowledge and skills will students need to achieve the learning goals?

- What types of activities will help students build the necessary knowledge and skills?

- What teaching strategies and instructional approaches will best support learning?

- What resources and materials (texts, multimedia, interactive tools, real-world applications) will enhance understanding?

By aligning learning activities with clear objectives, authentic assessments, and active learning principles, instructors can create meaningful and engaging courses that foster deeper understanding and long-term retention.

For additional support, the Center for Teaching Excellence offers consultations on course design, active learning strategies, and inclusive pedagogy—all of which contribute to effective learning experiences.

Sources and Attribution

Primary Sources

This section is informed by and adapted from the following sources:

-

Stapleton-Corcoran, E. (2023). “Backwards Design.” Center for the Advancement of Teaching Excellence at the University of Illinois Chicago. Retrieved April 2025 from https://teaching.uic.edu/resources/teaching-guides/learning-principles-and-frameworks/backward-design

- Available at: UIC Teaching Guides

- Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Understanding by Design.

- Available at: Vanderbilt CFT Website

Use of AI in Section Development

This section was developed using a combination of existing research, expert-informed insights, and AI-assisted drafting. ChatGPT (OpenAI) was used to:

- Synthesize key concepts from Backward Design and Understanding by Design (UbD) into a clear and practical framework for instructors.

- Develop structured explanations and examples to help instructors apply backward design principles effectively in course planning.

- Enhance readability and coherence, ensuring that the material is both theoretically grounded and practically applicable.

While AI-assisted drafting provided a structured foundation, all final content was reviewed, revised, and contextualized to ensure accuracy, alignment with research, and pedagogical effectiveness. This section remains grounded in scholarly and institutional best practices and respects Creative Commons licensing where applicable.

Media Attributions

- BD-Triangle-V3 (1)

- BackwardDesignFramework-V5 (1)

- 3layerConceptualModel-V2

- 3layerModelwBubbles-V2

- BDcircularReasoning-V2-1

- BD-whereTo