This chapter examines the music of international solidarity with Timor-Leste during the Indonesian occupation from 1975 to 1999. Ranging from popular songs composed by local artists in solidarity movements, classical compositions by recognised composers like Martin Wesley-Smith, and songs donated by major international acts like U2, it surveys the contribution of musical artists to the international solidarity movement. The paper also examines the links between these artists and solidarity movements in Australia, Portugal and elsewhere, and the critical role of East Timorese diaspora musicians in forging these connections.[1]

It is argued that music played a critical role in the history of international solidarity, and particularly in extending the reach of these movements among younger people, providing entertaining and emotionally engaging content to build channels to other forms of activism. Musical acts became entertainments for solidarity events and were especially central to community radio shows organised by activists, wherethey was critical to both format and content. Notably, solidarity acts frequently formed in collaboration with East Timorese diaspora musicians, whose greater level of awareness of the campaign for self-determination informed the local musicians in the bands themselves, and the wider audience. Like the solidarity movement at large, the period from 1975 saw musical solidarity commence at the local level, to become national, and then global in reach. This chapter examines that progression, which mirrored developments in the international solidarity movement at large.

Nationalist music and the East Timorese diaspora

As the long era of Portuguese colonialism came to an end, East Timorese nationalists used songs and traditional music as a medium to convey the message of nationalism. Early nationalist poets such as Borja da Costa, and musicians Abílio and Afonso Araújo also converted many traditional East Timorese songs, with newly penned nationalist lyrics. Drawing on East Timorese experiences of Portuguese colonialism, these became vehicles for depicting the injustices of colonial social relations, and the case for independence, such as the anthem Foho Ramelau, which urged East Timorese to “Awake! Take the reins of your own horse / Awake! Take control of our land”. Written in Tetun, these new forms of popular nationalist culture combined “traditional form with modern nationalist themes” (Leach 2017: 63). Indeed, the Fretilin literacy manual, a prime vehicle for early East Timorese nationalism, had itself referenced popular songs (Casa dos Timores 1975: 22-3; Leach 2016):

Abílio Araújo would become a key member of the diplomatic front in the first decade of the occupation. One month before the Indonesian invasion, the Jornal do Povo Maubere noted that 1,000 discs of Foho Ramelau and “other revolutionary songs” were being produced by Araújo with the help of the Committee of Angola in the Netherlands.[2] Araújo would release two albums of this music in the early years of the Indonesian occupation, signalling a crossover to the arena of international solidarity. This was an early signal of how important the East Timorese diaspora would become to the articulation of cultural nationalism. As Siapno (2013: 453) notes, the East Timorese national anthem Pátria, Pátria was lyrically composed over the telephone between the brothers Afonso Araújo in Timor, and Abílio outside the territory. This importance was tragically reinforced by the violence of the invasion, which killed many of the early visionaries of East Timorese nationalism within the territory, including the poet Francsico da Costa Borja, and Afonso Araújo, co-composer the national anthem (Siapno 2013: 440). East Timorese diaspora musicians would later come to foster important links with international solidarity movements, and in collaborations with musicians in other countries, contribute significantly to the rise and spread of the music of international solidarity over the period from 1975-1999.

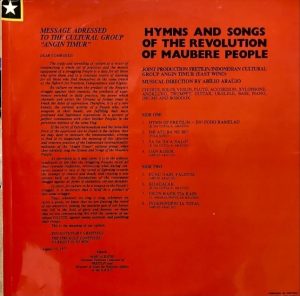

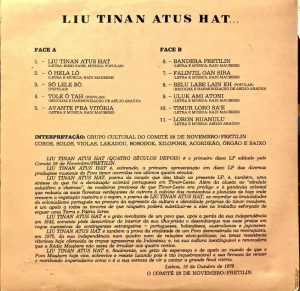

Early examples of East Timorese diaspora music were the two albums by Abílio Araújo, a senior Fretilin figure who by 1975 was resident in Portugal. Hymns and Songs of the revolution of the Maubere people (1977), also known as the “red” album, was released by the Comite 28 November/Abílio Araújo. Tracks included the “Hymn of Fretilin (Foho Ramelau)”, “Funu Nain FALINTIL (Falintil’s struggle)”, “Kdalalak” and others. The red album was followed in 1978 by “Liu Tinan Atus Hat” (“For over a century”). As long-term Australia-East Timor Association (AETA) and Timor Information Service activist John Waddingham recalled,[3] the “Atus Hat” recordings were of particular interest to solidarity activists at the time “because it included Abílio’s arrangements of music/songs taken from resistance-run Radio Maubere broadcasts”, such as “Ô Hela Lô”, “Bandera Fretilin” and “Falintil Oan Sira”. This link between the radio service run by Fretilin from the “zonas libertadas” in occupied East Timor, via Darwin, was the only source of communication from within the territory. The recording therefore represents a transitional point, as the domestic political-military and international diplomatic wings of the resistance were first separating. As Lurdes Pires would recall,[4] smuggled recordings from the diaspora would in turn later be played in occupied East Timor, highlighting the joint production and circulation of cultural nationalism between the two branches of the resistance.

Waddingham recalls that one of the earliest records, a 7-inch 45rpm single of Foho Ramelau and Kdadalak (1976) “engendered a strong emotional connection to the nationalist cause (Foho), and ‘ordinary’ Timorese (the traditional music ‘O hele o’ form).” Waddingham found the content of traditional songs, with new nationalist lyrics, to be especially engaging:

Waddingham recalled that another early recording which contributed to what he called the “bonding experience” was a 45rpm EP produced by the Portuguese Red Cross, which recorded four songs by a children’s choir in refugee camps in Portugal.

Music and solidarity activism

In Australia, the emergence of groups like the Australia- East Timor Association in 1975 provided an early base for international solidarity music. Remarkably, the first solidarity songs emerged as early as 1975, with Phil Noyce’s Songs for East Timor (AETA, 1975). The first of these was the “Ballad for East Timor:”

The Indonesians were able to see, the Timorese living better and free…

The story of Timor is sad and it’s true, if you want to help, there’s a lot you can do

Ask our PM to stop military aid, to the Indonesian generals, who did Timor invade.

Signalling the importance of the East Timorese diaspora, an early issue of AETA magazine also reprinted the Tetun lyrics of a second track called “Ita Timor Oan Sira ne” (We are the people of Timor), which had been “chosen and sung by members of Melbourne’s East Timor community”.[5] Waddingham recalled that the “two songs were put together by activist musos (Roger King included) in Melbourne in late 1975.” Roger King remains an active member of AETA today. One of these was Tony Simpson’s song “Which side are you on?”, which was first sung at a “rally of FRETILIN sympathisers” in Melbourne on December 9, 1975,[6] just two days after the Indonesian invasion of Dili.

The feeling of “connection” generated by these songs would prove essential to solidarity work, and play a special role in the emerging international solidarity movement, including community radio shows. As Waddingham reflected in 2023, solidarity music:

“East Timor Calling” 1977-1980

By 1977, a handful of AETA members had formed a media group which presented a regular program about East Timor on Melbourne community radio station 3CR. East Timor Calling was broadcast from January 1977 to 1980, with content prepared and presented by volunteers, including mainstays Rod Harris, Guat-kin Chew, Julia-Ann Ellis, Cecily Gilbert, Peter Lynch and Glenda Laslett. As Gilbert remembers,[7] the 15-minute show had a broader reach than simply Melbourne, including her hometown of Brisbane: “The program went to air live in Melbourne…. and for short periods, it was also replayed on other public radio stations (e.g. in Brisbane and in Canberra)”. Each episode opened with Foho Ramelau, and ended with the show closing theme of Kdadalak. Notes held by CHART indicated that “music composed by Martin Wesley-Smith” was played in episode 44 of the program on 24 November 1977, accompanying a “reading of poem by Francisco Borja da Costa”. Other notable show content included interviews with activist Denis Freney on Fretilin’s resistance in occupied Timor (1977), reports on Fretilin’s arrest of the inaugural President Xavier do Amaral (1977), Mari Alkatiri’s statement from Mozambique on negotiations (1978), and interviews with Brian Manning and Rob Wesley-Smith on the circumstances of Alarico Fernandes’ capture or surrender in 1979.[8] Jim Dunn, Jill Jolliffe and Helen Hill were also guests on the weekly broadcasts.

For Waddingham, the music played was not incidental, but central to the program, as it “caught the ear of listeners in ways which plain reportage never could. The music was a medium… in its own right, of communication about East Timor.” Nonetheless, technical challenges limited the ability to broadcast the types of songs Waddingham personally found more effective.

These challenges also affected the ability to re-broadcast the Radio Maubere[9] recordings made in Darwin by Communist Party activists, evading the Federal police to pick up the signals from the Fretilin transmitter in East Timor. As Waddingham recalled, “new revolutionary-era songs were written and performed in East Timor after the invasion, but the Radio Maubere broadcasts as recorded in Darwin were of insufficient quality to re-use on e.g. community radio in Melbourne.”

Happy Birthday East Timor

Activism among musicians was not limited to Melbourne. A play Happy Birthday East Timor was performed at Brisbane’s La Boite Theatre, from 18 November to 10 December 1977, with a special performance on Wednesday December 7 to mark the second anniversary of the Indonesian invasion. The play was especially notable for starring the actor Lindy Morrison, who would later become famous as the drummer in the internationally acclaimed Australian band The Go-Betweens. The promotional blurb for the play read:

The Brisbane play was reported in the East Timor Calling program number 43, on 17 Nov 1977. Referring to the Queensland police branch dedicated to investigating political activists, which reflected the state’s peculiar authoritarian political culture of the time, Gilbert notes that “apparently, Queensland Special Branch couldn’t resist turning up on opening night”.

Outside Melbourne, local level solidarity music was already emerging in other Australian cities, especially those with significant East Timorese diaspora populations. In Darwin, the well-known activist (and elder brother of composer Martin), Rob Wesely-Smith wrote The (Star-Spangled) East Timor Banner in 1978, at a time when the United States was supplying Bronco OV10 ground attack planes to the Indonesian military to be used against the East Timorese resistance.

Oh say can you see by the dawn’s early light

What so murderously seen at the twilight’s last gleaming?

Who’s broad stripes and bright stars through the perilous light

From the Broncos it flies, oh so gallantly streaming!

In Darwin, the well-known Indigenous group the Mills Sisters wrote songs for Timor throughout the 1980s. As Lurdes Pires recalls,[10] June Mills was especially active. Lurdes Pires remembered another local act, the Sexy Camp Dogs, singing several East Timorese songs, and dedicating them in live performances to the East Timorese residents of Darwin. In Sydney, the veteran AETA activist Jefferson Lee – with a life-long connection to the local music scenes – was renowned for promoting Timor solidarity through concerts, throughout the 1980s and 1990s.

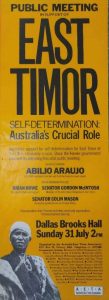

Four “moments” of musical solidarity

Interviewed in 2023, John Waddingham identified four “particular moments” of musical solidarity in Australia, which stood out for him in the first decade of the occupation. Alongside the role of music in AETA and 3CR’s East Timor Calling, he identified the East Timorese community performing the Tebe-tebe dance and music at the significant public meeting and protest at the Dallas Brooks Hall in 1983. This event was associated with the first visit by Fretilin representatives since 1976 (Abílio Araújo and Roque Rodrigues), and made national headlines when the new Prime Minister Bob Hawke prevented the Minister for Defence Support, Brian Howe, from speaking at the event. The protest attracted some 1500 people and was considered a major success by the Australian solidarity movement of the era.

Third, Waddingham recalled a number of politically active Melbourne East Timorese, many of whom were UDT-associated refugees from 1975, performing in traditional costume outside the famously contentious Australian Labor Party (ALP) National Conference in Canberra in 1984. Elected in March 1983, the Hawke government to use the 1984 ALP national conference to water down a stronger resolution condemning the occupation of East Timor, which had been passed at the 1982 National Conference, thanks largely to AETA activists within the party. Fourth, and highlighting other dimensions of regional solidarity, Waddingham recalls that a cassette tape of East Timorese resistance music was smuggled across the Papua New Guinean border and circulated in the late 1970s to members of the West Papuan independence movement, “choosing Timorese resistance music as a ready-made way to communicate a sense of East Timorese nationalism to West Papuan nationalists”.

The early 1990s: Solidarity music at the national level

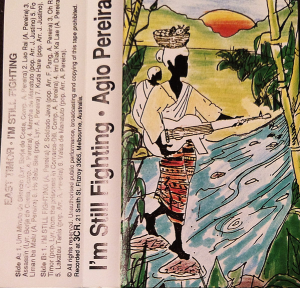

By the turn of the 1990s, solidarity music in Australia started to reach beyond local acts, to the national level. Perhaps the most notable of this era was Agio Pereira’s 1990 song “I’m Still Fighting”, which featured prominently in John Pilger’s 1994 documentary Death of a Nation; a film which created a significant impact internationally. Like many diaspora East Timorese, Pereira had first lived in Portugal, where he had performed in the Coro Lorosa’e choir, backing Abílio Araújo’s album recordings of the late 1970s,[11] and then became a long-term activist resident in Australia. Pereira would later become Minister of the Presidency of the Council of Ministers in several of Xanana Gusmão’s post-independence governments.

At this time, reflecting the increasing reach and impact of the solidarity movement generally, several nationally renowned Australian bands began to compose songs about East Timor’s struggle for independence. Examples included the Wild Pumpkins at Midnight’s 1990 song, “Hooray Hooray”.

There’s a war on 200 miles away

Another politician’s shame

We’ve got to keep our trading face

And let them get on

With wiping out a race

So hooray hooray

I made my extra dollar today…

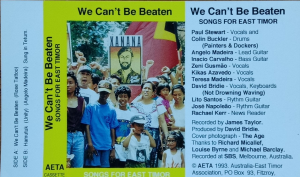

More high profile were The Painters and Dockers, led by Paulie Stewart, brother of Tony Stewart, one of ‘Balibo Five’ journalists killed by Indonesian special forces in October 1975. Already established as a major independent alternative musician, Stewart formed “The Dili All-stars” with East Timorese diaspora musician Gil Santos and others after the arrest of Xanana in 1992. Their Dili All-Stars – AETA Songs for East Timor, recording was released on cassette in 1993. Their first release amended lyrics to “We can’t be beaten” by the Australian band Rose Tattoo, with Tetun lyrics added, to turn the song into an anthem for East Timor’s independence, “Ukun rasik an”. The tape also included a track in Tetun called Hamutuk (Unity). According to Stewart, 500 tapes were smuggled into East Timor with the help of Melbourne University students.[12] Drawing on the higher profile of The Painters and Dockers, Stewart also released the song “Divvy van” in 1998, which included a verse which referenced the 1991 Santa Cruz massacre. The Dili All-Stars later released the well-known track “Liberdade” in 1999, in the lead up to the United Nations Mission in East Timor (UNAMET) led independence referendum of August 30,1999. With many line-up changes since, the band still performs today.

At the very apex of Australian bands, and a well-established international act, Midnight Oil joined in the international solidarity movement with a recording of “Kolele Mai” in 1993. This track appeared on the compilation CD “20 Years of Resistance to Genocide in East Timor” in 1996. With original lyrics in Tetun penned by Borja da Costa, an English translation was provided by the journalist and activist Jill Jolliffe. Notably, this involved collaboration with more established musical activists, as Martin Wesley-Smith had “arranged the Timorese traditional song Kolele Mai for choir, then got a choir together to record it for Peter Garrett and the Australian band Midnight Oil, who then added extra material and released it as a single”.[13]

What is it that makes your corn not grow?

What is it that makes your rice not flower?

What is it that makes your stomach not full?

What is it that makes your sweat not dry?

Some say you are lazy, some say you are stupid

Some say it is stupidity, others say it is poverty

What is the reason for it?

Who, who, is really responsible?

Local band case study: Relish

Far less famous was the local Brisbane band, Relish. This case study is instructive, however, as it demonstrates the critical links forged between local musicians and the East Timorese diaspora, and the way East Timorese activists collectively encouraged and supported efforts of solidarity acts at all levels. A mid-level band in Brisbane in the mid to late 1990s, the band’s bass player Afonso Corte-Real was a diaspora musician who joined the band in 1996, after meeting the author in Brisbane’s largest East Timor solidarity group, Action in Solidarity with Indonesia and East Timor (ASIET). This made the new band the inevitable choice of band for ASIET and other solidarity events. ASIET had an important and distinctive focus linking Timorese solidarity with the Indonesian pro-democracy Reformasi movement. Notable visitors to Australia sponsored by ASIET in those years include Dita Sari and other Indonesian trade unionists.

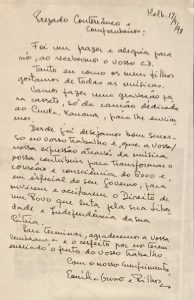

Corte-Real’s contribution in focusing the band on East Timorese solidarity was quickly evident in their earliest gigs at ASIET events, and in the choice of music that followed. As the band became more established it played more popular venues, enabling the songs to reach a wider audience. The band covered the Wild Pumpkin’s “Hooray Hooray” in early performances, and their own song “Xanana Vive!” followed quickly. Written in 1996 and recorded in 1997, the song received radio play of the local community radio station 4ZZZ, and at live gigs was usually introduced by Corte-Real speaking briefly about Timor-Leste’s struggle for independence. The CD recording opens with Corte-Real being asked in Portuguese “Onde está Xanana?” (“Where is Xanana?”), to which he replies “Xanana está na prisão” (“Xanana is in prison”). Corte-Real sent the CD to contacts in Portugal, who reported that it had been played on international radio and heard over East Timor. In a demonstration of the way East Timorese diaspora activists openly encouraged artistic solidarity, the band unexpectedly received a letter from Xanana’s wife, Emilia Gusmão, who was then resident in Melbourne. The letter, from 17 April 1998, stated (author’s translation from Portuguese):

“Dear Countrymen & Companions

It was a pleasure and happiness for us to receive your CD. Both my children and I like all the music. We will make a recording on cassette, just of the song dedicated to Comrade Xanana, to send him. We wish you success from now on in your work and, that your/our expression through music can contribute to transform the heart and conscience of the people and especially your government, to listen to and accept the right of a People who struggle for their liberty and the Independence of their country. We thank you for your memory and respect for sending us your work.”

With our compliments

Emilia Gusmão and children

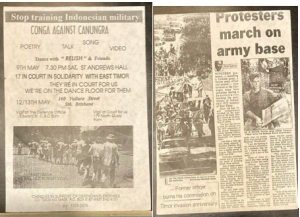

Providing entertainment at solidarity events proved a regular feature of the band’s activities. These performances show the variety of solidarity events conducted in and around Brisbane in the second half of the 1990s. Of particular importance to Brisbane activists was the proximity of the Australian Defence Force’s “Land Warfare” Base at Canungra, where controversial training programs with Indonesian Kopassus special forces were conducted. On August 23, 1997, Relish played an event for activists at the Canungra School of Arts, followed by a protest at the Canungra Army base on the theme of “Stop Training Kopassus”. Nine protestors were fined after the event. The same combination occurred again on December 7 that year, in a protest marking the 22nd anniversary of the invasion, which resulted in 19 arrests. This was followed on 9 May 1998 by a “Conga against Canungra” event in Brisbane, to raise funds for defendants arrested at the December protest, including a former army officer Terence Fisher. One year later, Relish played a benefit Tulun Rai Timor, this time raising funds for four activists arrested at another Canungra protest in December 1998. Later in 2001, Afonso Corte-Real would write “Labarik Sira Hotu” (All the children)”, which was used as an anthem for the 2001 Constitutional Assembly Elections in Timor-Leste.

Xanana Vive! (Lyrics: Leach, 1996)

Mountains arise

when the storm hangs heavy down

We’re waiting for the day you’re gonna

Walk back into town

Xanana Vive!

That flag is a knife

It bleeds red to white

This town

We’re waitin’ for the day

You’re gonna

Burn that flag to the ground

The late 1990s: International level

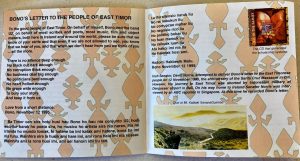

The Santa Cruz massacre of 1991 put the case of East Timor squarely back on the international stage. By the mid-1990s, following the award of the Nobel Peace prize to Jose Ramos-Horta and Bishop Belo in 1996, higher level international acts began to engage with the East Timor issue. One example was the Australian-issued compilation CD Love from a Short Distance 1996, which not only contained a poem from U2’s Bono, but also included his “Letter to the People of East Timor:”

To the good people of East Timor. On behalf of myself, Bono and the band U2, on behalf of most scribes and poets, most music, film and object makers, both here in Ireland and around the world, please be sure that we know of your strife and that even if we are not allowed to see, you know that we hear of you, and that when we don’t hear from you we think of you…all the more.

There is no silence deep enough

No black out dark enough

No corruption thick enough

No business deal big enough

No politicians bent enough

No heart hollow enough

No grave wide enough

To bury your story

And keep it from us.

Love from a short distance. Bono, November 12, 1995.

The compilation CD also included background by academic and activist Sara Niner, in the form of a short biography of Xanana Gusmão. As the liner notes detailed, Irish Senator David Norries had attempted to enter East Timor in 1995 to deliver Bono’s poem – inspired by the Santa Cruz massacre of 1991 – on the fourth anniversary of the killings. The poem was turned into a song by the group Soma, which appeared in the compilation, and included a Tetun rendering of one of the verses. The CD also included audio of Senator Norries reading the poem aloud to an Australian journalist in Singapore, after his failed attempt to enter East Timor. Other tracks were donated to the collection by major artists such as Billy Bragg, and the Australian Indigenous band Yothu Yindi.

Also notable that year was the Canadian compilation CD 20 Years of Resistance to Genocide in East Timor from the Hands Free label (1996), which included tracks from U2, Peter Gabriel, Midnight Oil, Buffy St Marie, and Ginger Baker, alongside diaspora musicians like Agio Pereira. The CD also included a track from “Abé ho Aloz”, referring to the diaspora activist Abé Barreto-Soares, who performed regular musical and poetry gigs in Canada in the 1990s, and was also well-known in Portuguese solidarity circles as a performer and poet. Funds raised from the CD went to the Canadian East Timor Hope Foundation. While the track “Love from a short distance” did not appear on this compilation, U2 authorised another track, “Mothers of the Disappeared”, for inclusion.

Portugal

With its 500-year colonial connection, and considerable East Timorese diaspora, Portugal was another important site for international solidarity with Timor-Leste, and musical acts in Portugal reflected this connection. In the late 1970s, members of the early solidarity choir Coro Lorosa’e, which backed many of the tracks on the Abílio Araújo albums, included the major literary figure Luís ‘Takas’ Cardoso de Noronha, the activist Agio Pereira, and UDT figure Antonio Ribeiro, who was a professional musician. Lurdes Pires recalls that the choir also included several Portuguese supporters.[14]

Pires remembers that alongside live performances, and producing music on cassette, Coro Lorosa’e conducted education workshops on the political situation in Timor, in Portugal and elsewhere. Notably, some of the group’s music originated from Radio Maubere itself, which was then performed live in Portugal, demonstrating the ongoing links with the resistance within East Timor. In a mutually supporting process, the Timorese diaspora recorded these songs, and later wrote new songs which were sent to students in Indonesia, including RENETIL members, and to other groups supportive of the Timorese, including one in the Maluku islands. These tapes were smuggled into East Timor itself, and formed part of a wider network of information organised in part through TAPOL and Carmel Budiardjo. Later in the occupation these songs could be heard in East Timor over international radio. As Lurdes Pires noted, this made the activists’ voices known to Timorese in the territory itself: “when we returned to Timor, some people in the resistance knew our voices from the radio, though we’d never met”.

Also notable in Portugal was the music of José Pedro Amaro dos Santos Reis, who lived part of his early life in Portuguese Timor, where his father was stationed. At the age of 22, Zé Pedro founded Xutos & Pontapés, one of the best-known Portuguese rock bands of its era, which featured at the Timor Livre (Free Timor) concert in 1994 at Centro Cultural de Belém, in Lisbon.[15] Notable solidarity songs included Outro País and Coro da Primavera. A documentary on Zé Pedro’s life was later shown in Dili (Somos Portugueses 2020).

Also prominent in the mid-1990s were the Delfins, with their song “Soltem os prisioneiros” (Free the prisoners), which originally referred to Xanana Gusmão and others, but was dedicated in live shows in November 1994[16] to the East Timorese youth who had recently scaled the fences of Embassies in Jakarta, to seek asylum as part of a series of protests at APEC.

Also well known in the Lusophone world is the East Timorese composer and musician Simão Barreto. Born in East Timor in 1940, Barreto went to Macau at the age of 18 to study at seminary, later enrolling in the Academy of Music. Obtaining a Gulbenkian Foundation scholarship to study at the National Conservatory of Music in Lisbon, Barreto finished a composition course, and joined the Portuguese National Radio Symphony Orchestra, later returning to set up the Macau Conservatory in 1989. Barreto recorded several volumes of choral music, including “the calling of the birds in mountains of Timor”. Perhaps most notably, Barreto orchestrated the national anthem, Patria, Patria. Siapno (2013: 448) movingly recounts the musical reunion of Barreto and Abílio Araújo in 2012 in Dili, at a performance which included his nephew Abe Barreto and others.

Lurdes Pires later reflected on the role of music in the East Timorese diaspora, arguing that it became a central to maintaining a sense of national identity in exile: “we learned to be Timorese outside the country, we knew the songs before, but they affected us more in the diaspora when we longed for home. And then passed that on to our own children, through music”.

Martin Wesley-Smith

Solidarity music was not limited to folk or rock songs. Spanning all the eras above was the enormous body of work produced by the well-known Australia composer Martin Wesley-Smith. Composing music for East Timor from 1976, Wesley-Smith’s work included many collaborations with twin brother Peter who “was essential with the history and words”. These projects received “on-going assistance” from their older brother, the well-known solidarity activist Rob Wesley-Smith.

Highlights of Wesley-Smith’s compositions include the 1977 audio-visual Kdadalak (for the Children of Timor) which featured images from the English photojournalist Penny Tweedie, who had worked in East Timor in 1975. In 1984, Wesley-Smith composed Venceremos! (“we will win”) to protest the “Hawke Labor government reneging on its promised support for East Timor”. Two years later he composed Silêncio, described as an “experimental multimedia work about the silence of Western governments regarding East Timor’s plight”. As noted above, he also arranged the song “Kolele Mai” for Midnight Oil’s recording in 1993.

Other work included the full-length opera Quito, based on “the life and death of Francisco Pires, a young East Timorese man in Darwin”, which won the ABC Classic FM Recording of the Year, the audio-visual chamber work “November 12 1991” (1995), followed by a 1999 the audio-visual work X (for “Xanana”), and the audio-visual production Welcome to the Hotel Turismo the following year (Dunlop 2020).

Sydney clarinettist Ros Dunlop performed Wesley-Smith’s work internationally, and later became a regular attendee at Timor-Leste Studies Association conferences. Dunlop (2020) recalled:

Wesley-Smith’s contribution to East Timorese solidarity were recognised at the highest levels. Martin received the Order of Australia in 1998, and all three brothers received Timor-Leste’s highest honour, the Ordem de Timor-Leste, in 2014, for their lifelong contributions to solidarity with East Timor. José Ramos-Horta described Wesley-Smith as a “model political artist” (Dunlop 2020):

Martin Wesley-Smith passed away in 2019.

Conclusions: Music and Solidarity Activism

This chapter has examined the music of international solidarity with East Timor’s campaign for self-determination. It has been argued that music extended the reach of solidarity movements, offering emotionally engaging content to support other forms of activism. Beyond their obvious role as entertainments for solidarity events, songs popularised key messages of the independence movement, helping to broaden the appeal of solidarity movements over time. Music was also central to community radio shows organised by activists. Notably, solidarity acts frequently involved collaborations among local artists and East Timorese diaspora musicians and, who played a critical role in developing these acts as vehicles for political mobilisation. The East Timorese diaspora was also quick to support artistic solidarity endeavours at all levels, recognising it as a critical element of building the international campaign for self-determination. Mirroring the expansion of the solidarity movement at large, it is possible to trace the growth of the music of solidarity from the local to the national level, and then to the international arena, over the period of 1975-1999. Songs of international solidarity promoted political mobilisation and recruitment into activists networks, adding emotional depth to “raw data” on the political situation in East Timor. In these ways, the music of solidarity became a key factor in mobilisation, recruitment and activism in the international solidarity movement for the restoration of Timor-Leste’s independence.

References

[1] This chapter limits itself to the time frame of the occupation, from 1975-1999, and as such, does not examine a new generation of artists from 1999 onward (see e.g. Schlicher and Tschanz 2019b). Likewise, given the focus on the history of international solidarity, it does not examine resistance-era music within Timor-Leste itself, though authors like Farram (2020) have investigated this dimension. There are also important studies of the traditional music of Timor-Leste. See e.g. Dunlop (2014), and Barreto and Araújo (1987).

[2] See Jornal do Povo Maubere, 1 November 1975, https://chartperiodicals.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/timor-leste-10-p.pdf

[3] Interview with John Waddingham, 2023.

[4] Interview with Lurdes Pires, 2024.

[5] Australia-East Timor Association newsletter, 1975.

[6] Timor Information Service newsletter, 1975

[7] Interview with Cecily Gilbert, 2023.

[8] Samples of the “East Timor calling” show can be heard on the CHART website. https://timorarchives.wordpress.com/2009/11/02/etc-digitisation/

[10] Interview with Lurdes Pires, 2024.

[11] Interview with Lurdes Pires, 2024.

[12] Kylie Northover, “No, we didn’t steal Picasso’s Weeping Woman: Paulie Stewart,” The Age, 8 December 2022.

[13] See “Martin Wesley-Smith: Musical Activist,” 2009, https://shoalhaven.net.au/~mwsmith/mw-s,_musical_activist.pdf

[14] Interview with Lurdes Pires, 2024.

[15] The performance can be seen here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kP5Wg0sIVoA

[16] Performance available here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HMJxCVrVaqs

Media Attributions

- Leach fig 1.1

- Leach fig 1

- Leach fig 3

- Leach fig 4

- Leach fig 5

- Leach fig 6

- Leach fig 7

- Leach fig 8

- Leach fig 9

- Leach fig 10