Timor-Leste’s people won their independence first and foremost through their own efforts, in the course of a quarter-century of resistance to colonial rule. “To resist is to win,” resistance leader Xanana Gusmão declared in a widely embraced slogan. Standing in support, and influential in the work of the resistance movement’s “diplomatic front,” was an international solidarity movement spanning the continents.

In a retrospective examination of this movement after the end of Indonesian rule in 1999, British-Indonesian activist Carmel Budiardjo described the solidarity movement as “a weapon more powerful than guns”.[1] In her account, it “contributed massively to informing public opinion and forcing governments and institutions to acknowledge the injustice and brutality of Indonesia’s invasion and occupation.” Meanwhile, “its persistence meant that governments were not able to ignore the legitimate demands of the people of East Timor”.[2] So, to persist was also to win.

She identified five phases of solidarity:

- “Support for Fretilin” (late 1970s)

- “Emphasis on human rights” (early 1980s)

- “Building an international solidarity network” (late 1980s)

- “Keeping East Timor permanently in the foreground” (early 1990s, after Santa Cruz)

- “Persistence meant that governments were not able to ignore the legitimate demands of the people of East Timor” (late 1990s)

This chapter explores the history of the solidarity movement as its role in the unlikely independence of Timor-Leste. I make three main arguments:

First, the solidarity movement was broadly successful in helping to keep the Timor-Leste issue alive internationally and changing the policies of some governments, largely though sustained persistence over time. The people involved changed, the groups changed, but solidarity was sustained and grew over the decades.

Second, the notion of “out-of-the-way places” is an argument that we need to see the importance of movements that are not well known, not based only in the centres of global politics such as New York and Washington and London and Tokyo and so on, but also in smaller countries and smaller cities. Movements operated in multiple languages alongside English and Portuguese. It is out-of-the-way governments that were the first to change their positions in the 1990s and speak out for East Timor’s right to self-determination.

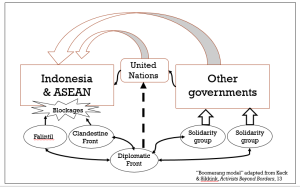

Third, the solidarity movement thrived due to its decentred “network” structure, with no attempt to impose a single party line, and its ongoing cooperation with Timorese resistance diplomats from both major exile political parties and then also with the National Council of Maubere Resistance, even while groups maintained full freedom of action. I think it is useful here to employ the “boomerang model” developed by political scientists Margaret Keck and Kathryn Sikkink (1998). In this model, social movements blocked by their “home” government turn towards social movements in other countries, who put pressure their own governments. These governments in turn put pressure the “home” government.

In the Timor case, the “home” government is the Indonesian occupying authorities, backed by regional allies in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). A transnational advocacy network helped the Timorese resistance by raising international awareness and, eventually, modifying the policies of overseas governments. The network then exerted a “boomerang effect” in which some solidarity groups were able to bring their governments on board as supporters of Timorese self-determination by 1999 (Ireland, Canada) while others lessened their support for Indonesian rule and quietly urged Indonesia’s government to improve the human rights situation in Timor-Leste (United States, Japan).

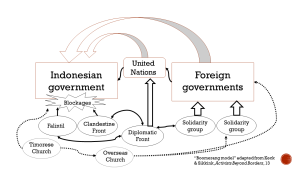

The Timorese resistance movement was not fighting its own government. It faced, rather, an occupying power that after 1978 controlled most of the territory. Efforts to internationalise the Timor-Leste struggle did gain some traction, but further blockages came from the united ASEAN support for Indonesian rule. Nevertheless, the Timorese resistance was able to internationalise its struggle through what it called a “three fronts” strategy, in which the armed resistance and clandestine movements funneled information to Timorese diplomats overseas. This “diplomatic front” in turn carried information and strategies to the solidarity movement in multiple countries, which lobbied their own governments. The UN and other international organisations also played important roles in the “boomeranging” of Timor-Leste resistance demands back to Indonesia from overseas. Figue 1 attempts to illustrate the model.

This model, of course, oversimplifies – as all models do.[3] The “three fronts” model was an announced resistance strategy, but the true picture was more complex. The role of the church as transmission belt for information and ideas is also vital. There were other actors, many of them invisible or overlooked. Clandestine activists increasingly had little need to operate through the diplomatic front. The overly-complex Figue 2 is an effort to capture some of the complexities. Yet overall, the model seems a useful representation of the solidarity movement’s role as what might be called, to borrow from Budiardjo, a boomerang more powerful than guns.

Internationalising resistance

The East Timor conflict was fought on the battlefield in the country and on the bodies of the Timorese people. It was also fought in the field of international public opinion – a rhetorical terrain in which both sides deployed ideas and bombarded the enemy with them. Though by far the weaker party, the Timorese resistance movement was able to use “weapons of the weak” to win out in the end (Scott 1985). Timorese activists explicitly told their overseas supporters that they had a place in the diplomatic front.[4]

The diplomatic front’s great success was in shifting global opinion – both that of publics and governments. By 1999, international pressure on Indonesia was strong enough that it could not turn back the Timorese vote for independence. The solidarity movement, for its part, help to shift the global context for debate about Timor-Leste away from ignorance and complicity, towards a situation in which the Indonesian occupation was no longer viable. The fight took place on discursive terrain – it was a battle of ideas and arguments outside the country, not just a guerrilla war inside Timor.

Independence movements can be global diplomatic actors, a process seen the diplomatic efforts of the Algerian independence movement, the Vietnamese independence movement, and the way activists in Korea, China, India and Egypt responded to the door to self-determination opened by United States president Woodrow Wilson in 1919, among many other examples (Connolly 2002; Brigham 1999; Manela 2007). Each of these studies shows independence movements fighting on diplomatic terrain as well as on the ground, making themselves transnational even while remaining nationalist (Sluga 2013).

The Indonesian state attempted to impose silences, while its rivals tried to shout through those silences. “Where history is silent, literature must speak,” writes Indonesian journalist and activist Seno Gumira Ajidarma (1997). In titles like “Indonesia’s Forgotten War,” “the hidden war,” and “a holocaust on the sly,” people concerned about East Timor made clear their goal to break silences, and to reach global audiences by “Telling East Timor” to the world (Taylor 1999; Australia-East Timor Association 1989; Komitee Indonesia 1980; Turner 1992). These strategies provide highly effective.

The first phase saw dark days of famine and killings, accompanied by tough times internationally as the cause of Timor-Leste became increasingly isolated. In her listing of solidarity movement phases, Budiardjo defines this period as a time that activists mainly provided “support for Fretilin,” the party that claimed to be the government of Timor-Leste. Fretilin’s resistance to Indonesian rule, both inside and outside the country, modelled itself on “Third World” liberation movements. Launched by the Vietnamese and Indonesian revolutions in 1945, this model was elaborated by 1970s movements against Portuguese or white-minority rule in Africa. In the words of Eduardo Mondlane, “Our struggle, apart from being a just struggle located in Mozambique, is at the same time an international struggle.”[5]

Frelimo asserted a status as the “sole representative of the Mozambican people,” the one over-arching liberation movement for Mozambique. Under lobbying by Fretilin minister Mari Alkatiri, Frelimo endorsed Fretilin as “sole representative” of the East Timorese people. Fretilin in turn reinvented itself from a social democratic party to one that looked to Third World examples and inspiration (Ramos-Horta 1996).[6]

Only in Portugal could Timor-Leste claim to be a public issue. Australian movements were highly active but politically marginalised. One way in which the emerging solidarity movement influenced Timorese resistance was in prompting a move towards the language of human rights. And this happened in out-of-the-way places as much as in places considered more central. Even Carmel Budiardjo attended her first solidarity rally for East Timor in Toronto, not in the UK.[7]

The East Timor Human Rights campaign, Syracuse, New York

As an example, I use the East Timor Human Rights Campaign, based in Syracuse, a town in upstate New York, emerging from the local peace movement (Syracuse Peace Council) during a time that anti-nuclear and human rights organising were very prominent in the United States. The group billed itself as “the only on-going organisation in the United States committed to organising and providing resources on East Timor at the grassroots level.”[8] Headed by Michael Chamberlain and Chin Fong, and receiving support from Clergy and Laity Concerned as well as the Asia Center, the group in its first year held 106 events in 55 cities, covering 22 of the 50 US states. Although based in a small city, the committee was also closely networked with like-minded groups. ETHRC documents show regular meetings with José Ramos-Horta, the Timorese representative at the United Nations, direct UN lobbying, multiple events, and international contacts such as a joint campaign with the Pacific Concerns Resource Centre, based in Fiji, and the Asian Forum on Human Rights. A brief on efforts in the US Congress went to a mailing list of 500 and ETHRC had a total mailing list of some 10,000 people.[9]

This was, in other words, a fairly strong movement, one strongly linked to other social movements critical of the foreign policy of the Reagan administration. Yet it has been largely ignored. I only learned about the East Timor Human Rights Committee because Michael Chamberlain was kind enough to share his files – and this was possible due to the work of Arnold Kohen – another early activist in upstate New York. Our stories are always incomplete, and there are many more to see if we look to out-of-the-way places and outside of already-archived collections. In other words, we need to know the story of the East Timor Action Network, which Chris Lundy discusses in his chapter, but we also need to look at other grassroots groups that did similar work in an earlier period that would lay the groundwork for subsequent work.

Information politics

This challenge in other words replicates the early movement’s main challenge, a blockage on information. As Professor Noam Chomsky wrote in an early letter to Sue Nichterlein at the DRET Office in New York: “It is most unfortunate that few Americans are aware of these events or their importance. When the facts become better known, as I trust they will, I have no doubt that the struggle for independence in East Timor will receive the support it deserves”.[10] From Australia, John Waddingham’s Timor Information Service also aimed to make decision makers more aware of events in Timor-Leste.[11]

But information did flow, and often though unexpected channels, and through other types of left-leaning solidarity and rights activism. As one example, Barbados-born pan-African activist Pauulu Kamarakafego (born Roosevelt Brown) campaigned for East Timor as part of the global movement against racism and war. He raised Timor and spoke in support of Fretilin in 1976 interview with Black World magazine. A seminar that same year in Senegal convened by Wole Soyinka issued a ““Declaration of Black Intellectuals and Scholars in Support of the People’s Struggle of West Papua New Guinea and East Timor Against Indonesian Colonialism” (Swan 2020: 243, 267). Similarly, Marisa Ramos Gonçalves in her chapter highlights the role of solidarity in Mozambique, which went well beyond government.

The 1980s saw a resurgence in overseas awareness and activism that would become known inside Timor-Leste, serving as encouragement to resistance forces.[12] The Commission for the Rights of the Maubere People (CDPM) and others centred suffering and the human rights of the Timorese people, a contrast to earlier liberation movement rhetoric, because that was effective in reaching Western audiences. CDPM’s digitised archives contain evidence of the new language of human rights coming to the fore. For instance, a public gathering in Spain – an out-of-the-way space for Timor activism – highlighted the right to self-determination in 1985.[13]

This shift towards “rights talk” (Ignatieff 2008; Mamdani 2000) came in part under Catholic influence. Meanwhile, secular solidarity movements’ “network coherence” was visible in annual gatherings of solidarity groups from Europe (under CDPM and TAPOL leadership) that invited leaders from the three major Timorese diaspora groups – Fretilin, UDT (Timorese Democratic Union) and Xanana’s new National Council of Maubere Resistance (CNRM), founded in 1988.[14] Solidarity group gatherings established a coherent network with a high degree of mutual trust and made sure that activism was in tune with Timorese wishes, as expressed through the three overseas representatives present. Timorese diplomats and solidarity activists renewed ties regularly at annual meetings of the UN Human Rights hearings in Geneva and the UN Decolonization hearings in New York.

The role of information was crucial: activists did not necessarily seek one form of action over another, but they prioritised telling the public about a “forgotten genocide,” “Indonesia’s secret war,” a “hidden Holocaust” and other framings that aimed to shock and inform. Information and awareness-raising seemed a pale form of activism, but it was deliberate. In the words of Julia Morrigan, co-founder of Canada’s Indonesia-East Timor Programme (IETP), “there is no doubt in my mind that Canadians, once they comprehend the brutality of the Indonesian occupation of East Timor, will be moved to protest our own nation’s complicity with the Suharto regime”.[15] So too throughout the movement. Raising awareness meant raising support.

The solidarity group consultations also made space for out-of-the-way places. For instance, they allowed Japanese activists, discussed in Mastuno and Furusawa’s chapter, to have a voice and thus de-centred Europe.

The East Timor Alert Network, Canada

In 1986, Elaine Brière then joined with other Canadians to form the East Timor Alert Network (ETAN), using a two-year start-up grant from the Canadian churches.[16] Two years later, a Canadian government official noted that “Indonesia is not a sufficiently flagrant violator to attract the attention of the public as some other countries do”.[17] ETAN aimed to change that. It had striking success in bringing an unknown issue to the eyes of many Canadians and in challenging government claims that Indonesian rule was “irreversible”. Brière travelled through Portuguese Timor in 1974. Her photos from the time featured in an Amnesty International Canada campaign for the 10th anniversary of the invasion, and Brière then joined with ten others in a meeting in Vancouver in 1986 convened by the Canada Asia Working Group of the Canadian churches, to create ETAN. The group concentrated on information and awareness-raising, public talks and workshops, seeking media attention, networking with other solidarity groups and lobbying the Canadian government and the UN.

ETAN’s attack on the Canadian government’s Timor policy was direct and ferocious. Leaflets spoke of “genocide” and drove home a figure of more than 200,000 deaths – almost one person in three – to show the scale of human rights violations. “Canada is an important member of a coalition of western governments that have been supporting the Indonesian government,” read one pamphlet distributed at vigils and public events. “Indonesia could not continue its genocidal war against the East Timorese without the diplomatic, economic and military support of western governments.” ETAN labelled Canada “one of Indonesia’s most loyal supporters” and called for a flood of letters to federal and provincial governments.[18] In response to one ETAN letter, a DEA official called for “a careful reply because these groups will publish it and get their letter writing mill in high gear”.[19]

Brière’s photographs had documented a way of life disrupted by forced resettlement. Now, her writing stressed the threat to Timorese Indigenous peoples.[20] This fit well with rising awareness of violations of Indigenous rights within Canada and globally.

A network structure, clearly responsive to Timorese aspirations and using transnational connections from person to person and within church bureaucratic structures, is evident in the documentary record of this campaign. ETAN’s files make the international network structure more visible. There is a prominent stress on Indigenous rights issues, for instance, seen through collaborations with the International Working Group on Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA) based in Denmark and the Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific Movement (NFIP). The reader can see the influence of Pacific islanders carried via the NFIP’s Motarilovoa Hilda Lini, a leader from Vanuatu. ETAN/Canada also deliberately chose feminist organisational structures and had a majority of women activists.

Federation and clandestinity

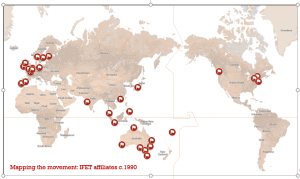

International networking in this period took on a more institutional form thanks to solidarity groups based in Japan. Japanese activists led the creation of a new International Federation for East Timor (IFET), mapped in Figure 3. IFET had a small token secretariat but made no effort to dictate actions to member groups or even to collect dues. It appeared as institutional platform and allowed improved access to UN forums, but it operated within the loose network structure, avoiding any potential struggles for control.

The transnational solidarity network continued to build slow momentum through the rest of the 1980s, albeit with peaks and troughs and in an often reactive fashion. Activists gradually developed their awareness of events in Timor-Leste and their contacts with Timorese inside and outside the country. Often lonely and isolated in spare bedrooms or church basements, they were fortified by the emerging transnational network structure and signs of continued resistance inside Timor-Leste. To recall the “boomerang model,” they very much identified with the Timor cause and saw themselves as contributors to its eventual success through their activism outside Timor-Leste. The stage was set, then, for an opportunity to move to a new level in 1991.

For many activists, everything changed with the Santa Cruz massacre, which brought the “clandestine front” to the centre of resistance. The clandestine front remains under-studied, though this is beginning to change. Clandestinity became method, with most activity conducted out of sight. While “information was centralized in the hands of a few people,” the goal of clandestinity became to “leave no trace behind”. (Nygaard-Christensen and Angie Bexley 2017; Siapno 2017). One effect of the Santa Cruz massacre was that some Timorese clandestine activists were forced into exile to avoid arrest, while several Timorese students overseas applied for refugee status and became influential overseas activists. The “new generation of resistance” inside Timor-Leste would also become a new generation of diplomatic resistance.[21] These new young CNRM representatives carried CNRM views into the countries where they lived. They also became members and guides to solidarity groups, strengthening the connection between the diplomatic front, the clandestine front, and solidarity groups.

Back to Canada

Three Timorese university students defected and sought refugee status in Canada in the early 1990s. The refugee pair shifted ETAN’s focus, linking up with younger activists, who took up East Timor as a symbol of global injustice and Canada’s complicity. ETAN did not lose its base of letter writers, religious people, and activists who had emerged from the peace movements of the 1980s and before, but it was energised and remade by the influx of the university-based “new radicals” of the 1990s. It built new support bases in Canadian trade unions and among people skeptical of the government’s embrace of economic globalisation. ETAN exploded with new chapters and new members after the Santa Cruz massacre, and the presence of young Timorese voices was central to this growth. ETAN/US, as described in Chris Lundry’s chapter, formed at this time.

Recruitment was aided further by ETAN benefit screenings in Vancouver and Toronto of the documentary film Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky and the Media, which used East Timor as a prominent case study.[22] Timorese youth leadership may be said to have peaked with the “Team Timor” tour of Canada in the lead-up to the 1997 APEC summit – a project conceived in Porto at one of the Jornadas sponsored by Professor António Barbedo de Magalhães and funded by the Portuguese University Foundation. Young activists put Suharto on trial, attempted a citizens’ arrest, and garnered global headlines. José Ramos-Horta headlined an alternative “People’s Forum” in Vancouver and APEC was firmly established as a venue for pro-Timor protest, a trend begun at the 1994 APEC summit in Jakarta when youth activists occupied the US embassy.

Documents in federal government files show that, despite what both sides thought, ETAN was actually altering the perceptions of Canadian government officials and starting to influence policy. One official wrote that “we have to do something to get ETAN off our backs”. Persistently bothering government officials is a remarkably effective strategy.

New communications technologies

Timor solidarity groups were early adapters of internet organising, which leant itself perfectly to the existing network structure. Activists had to devote much more time to reading words slowly scroll across their monitors, letter by letter, as they switched their phone lines to 300-baud (0.3K) modems to send and receive messages. There were no laptops and visual web interface options until later on; social networking remained a thing of the future; but internet capacity changed the shape of activism. Key here was the Association for Progressive Communications (APC) with national nodes in the US, Britain, Australia (Pegasus), Brazil (IBASE), Canada (Web), Nicaragua (Nicarao), Sweden (Nordnet) and others.[23] Charlie Scheiner of ETAN/US was the key figure on the solidarity movement embracing the internet before other groups. The open reg.easttimor list became especially important for sharing information, while closed groups and direct e-mail exchanges kept the global networks in touch and further entrenched group solidarity among the different local and national solidarity groups.

As two-letter country domain names became the standard everywhere except the US imperial centre, activists in Ireland harnessed the dormant .tp domain name technically assigned to “Timor Português”. It was in reality a domain utilised by the “Timor pejuang”, an Indonesian-language name occasionally given to pro-Timor solidarity campaigners.[24] This was one of the highly creative and attention-grabbing tactics employed by another solidarity group formed after Santa Cruz, the East Timor Ireland Solidarity Campaign (ETISC), which Budiardjo described as “one of the most effective solidarity groups”, covered in Tom Hyland’s chapter.

Malaysia and Southeast Asia

Meanwhile there was change in ASEAN solid support for Indonesia, also promoted by public opinion, as Gus Miclat’s chapter shows. In his words, the Asia-Pacific Conference for East Timor in the Philippines was a way of “breaking the silence” within Southeast Asia, thus disrupting the Indonesian government’s support systems (Miclat 1995). A year later, the newsletter of the new Asia-Pacific Coalition for East Timor (APCET, an acronym deliberately retained) was declaring that the 1994 gathering in Manila “showed the world what solidarity was all about”.[25]

APCET was, of necessity, a partly clandestine movement, operating in spaces of semi-legality in the semi-authoritarian contexts of the countries of Southeast Asia. For instance, it was possible to form an East Timor Information Network in Malaysia that aimed “to counteract the media blackout which has so far prevented more Malaysians from learning about the unspeakable military atrocities which are occurring right on our doorstep”. It held a vigil in the “NGO capital,” Penang, in 1992, drawing support from the local Third World Network and Consumer Association NGO circles.

A rally in Kuala Lumpur in 1994 was co-sponsored with 15 Malaysian NGOs, including the Cente for Orang Asli Concerns, an advocacy group for Indigenous minority groups. It was met with a violent response coordinated by the Indonesian embassy with the tacit agreement of Malaysia’s ruling UMNO government. ETIN, in other words, was seen as part of the wider human rights community in Malaysia, and thus associated with the opposition group and figures from the ethnic Chinese and Indian minority communities in opposition to the government.

Thus, when the APCET II conference convened in Malaysia in 1996 with 12 Asian countries and 6 other countries (Bangladesh, Nepal, Japan, New Zealand, South Africa, Mozambique, Canada, Ireland, Thailand, Burma, Singapore, Cambodia, Indonesia, Brunei, Philippines, India, Sri Lanka, Australia), it too faced violence by groups linked to the ruling party, and more than 100 delegates were arrested. Nevertheless, there was an impact on public opinion and even, by 1999, Malaysian government policy.[26]

Clamor por Timor, Brazil

There was a “Southwards” movement that decentred Europe and North America and made more space for activists based in the “Third World”. Faraway Brazil, for instance, saw the creation in Catholic liberation theology circles of the new group Clamor por Timor. It can serve as an example of the new groups formed after Santa Cruz, though it is less well known than others since many in the movement saw Brazil as out-of-the-way.

Clamor por Timor was founded by the “Grupo Solidário São Domingos” (GSSD), created in 1982 to translate books related to religion abut also increasingly important in opposing inequality in Brazil. One outgrowth was “Clamor”, which aimed to help political prisoners of the dictatorships in Latin America. In 1993, a dedicated Timor solidrity group emerged under the name Clamor Por Timor. Its work included newspaper articles, benefit concerts, exhibitions, protests and pressure on the Brazilian government.[27]

By the end of the 1990s, as Ramos-Horta affirmed in communications with solidarity groups, Timorese diplomacy was able to lobby foreign governments and access UN channels directly. The time of “diplomacy from below” was over; the boomerang effect had served its purpose. Solidarity groups, as he also acknowledged in his Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech, had been crucial to making this possible.[28] Without two decades of awareness-raising, protest and lobbying by solidarity groups, the conditions for Timor-Leste to become a top-level international issue would not have been in place.

Activism shifts governments

As independence neared in 1999, solidarity groups organised an observer mission and pushed their own governments to ensure that the referendum on self-determination took place and its results (78.5% in favour of independence) were respected. By this points, such governments as Canada and New Zealand had joined earlier supporters such as Portugal and Ireland in pushing for the right to self-determination. Indonesia’s strongest supporters, such as the United States and Australia, started to move during 1999 as well.

It is important here to note that Western governments in the 1990s slowly ended their loyal support for Indonesia. Grassroots activism in Ireland, as Hyland’s chapter shows, was important in shifting the Irish government’s position. In a small country well aware of its own colonial past, the Timor-Leste issue resounded. The organisational skills and accessibility of Tom Hyland and the existing Irish social justice networks that ETISC could draw upon would prove successful, as Ireland’s government was one of the first Western powers to embrace the Timorese right to self-determination. By 1995, its foreign minister walked out of a meeting with his Indonesian counterpart when the latter refused to discuss East Timor; well before 1998, Ireland was pushing for stronger international commitment to the issue. Already, Portugal had placed the Timor issue on the European Union foreign-policy agenda. Ireland’s 1996 presidency made Timor a “priority issue”.[29] So Ireland was the first significant Western country to offer solidarity for Timor-Leste – a change that was certainly prompted by its very vocal solidarity movement.

New Zealand and Canada shifted next. As Maire Leadbeater explains, New Zealand backed Indonesia on the basis that its occupation of Timor-Leste was “irreversible” (Leadbeater 2006). Once activists started to convince the New Zealand government that was not true, New Zealand stopped supporting Indonesia.

Canada was similar, first abandoning the belief that Indonesian rule was “irreversible” and then coming out publicly in support of the Timorese right to self-determination in November 1998. The statement came from Raymond Chan, a former human rights activist who was elected to parliament and named Secretary of State for the Asia-Pacific. Chan had met with ETAN activists in Vancouver shortly after his elevation to cabinet. (They later held a sit-in in his office.) He was one of the first leaders to meet Xanana in his Jakarta prison cell, where he agreed to help. The foreign minister of Canada, Lloyd Axworthy, met Ramos-Horta, heard the same requests, and also agreed to help. In this, they were over-ruling advice from their officials to be cautious.[30]

New Zealand and Canada teamed up in September 1999 to hold a meeting on East Timor on the sidelines of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit in Auckland. This was an unprecedented political aspect tacked on to an economic meeting. It mattered because Malaysia, Singapore and then other ASEAN countries agreed to attend, isolating Indonesia from its allies.

My argument is that public opinion forced multiple governments to attend and put pressure on Indonesia, and that was the result of years of persistent solidarity movement work. There is a revisionist view that says US president Bill Clinton’s intervention ended Indonesia’s effort to cling to Timor-Leste – but as Brad Simpson has shown with careful documentation (National Security Archive 2019), this is not the case. When Clinton did signal that US support for Indonesia was at an end, he did so while boarding the plane to Auckland.

Timor-Leste was on the global agenda due to a quarter of a century of persistence by Timorese resistance members and their overseas supporters. This chapter has argued that the solidarity movement was, in Budiardjo’s words, “a weapon more powerful than guns,” one used to good effect by a Timorese resistance movement that admitted its inability to win a military victory, but urged Indonesia to admit its own diplomatic defeat.[31] Country by country, the solidarity movement disrupted the Indonesian military government’s network of global support. It did so by employing languages of human rights, while using the concrete tool of first-generation internet communications technology within a loose transnational network structure with increasing internal cohesion that did not attempt to impose any command structures on its membership.

Transnational advocacy networks were vital in the late twentieth century to the popularisation of commitment to the self-determination of small states. In this sense, both Timor-Leste and the solidarity movement built on earlier models to define new spaces of possibility within the international system. Those spaces of possibility, expanded in the twentieth century, remain open in our own century.

References

[1] See Budiardjo (2004: 70). A shorter version of this article is online at https://www.tapol.org/news/international-solidarity-movement-east-timor-weapon-more-powerful-guns.

[2] Ibid, 69.

[3] Thanks to Vannessa Hearman, José Mauki and Trygve Ugland for corrections to an earlier version of Figure 1.

[4] For example Abé Barreto Soares, “East Timor: Towards the Year 2000,” paper presented at Ontario conference on East Timor, 1993. This and many other documents used here are available at the Timor International Solidarity Archive (TiSA), https://timorarchive.ca/.

[5] FRELIMO communiqué, 1974, cited in A. J. Venter (1975: 387).

[6] The occupation of Timor-Leste is chronicled, among other sources, in Magalhães (1992), Budiardjo and Liong (1984), Dunn (2004), Fernandes (2011), Jolliffe (1978), Robinson (2010), and Weldemichael (2013).

[7] Personal communication, Carmel Budiardjo.

[8] “A Report on the Activities and Plans of the East Timor Human Rights Committee,” 1980, ETHRC papers, in timorarchive.ca.

[9] Chamberlain, “From Upstate New York” chronologies, ETHRC papers; personal communication, Michael Chamberlain.

[10] Chomsky to Nichterlein, 29 November 1976, document in author’s possession.

[11] Waddingham to Kohen, 8 July 1982, document in author’s possession.

[12] In Xanana’s words: “Your affirmation that no-one must consider ours a lost cause does not just provide moral support. It holds inestimable significance for us as we conclude the tenth anniversary of our resistance to the power which has so brutally occupied our homeland,” “Fretilin invites UN Secretary General for consultations,” text of radio broadcast by Xanana to Avebury, TAPOL Bulletin 72, November 1985, p. 5. See also “Exchange of messages with FRETILIN,” TAPOL Occasional Reports no. 1, 1985.

[13] See for instance “Jornadas Pro-derechos Humanos y Autodeterminación en Timor-Este,” CIDAC, http://xdata.bookmarc.pt/cidac/tl/TL4091.pdf.

[14] Most commonly, Mari Alkatiri or José Luís Guterres represented Fretilin, while João Carrascalão spoke for UDT. Ramos-Horta initially attended on his own behalf and as a figure who had Xanana’s confidence, then in a more formal capacity. None were initially accompanied by support staff, and they generally participated actively in all debates at the meetings in addition to each presenting themselves.

[15] Statement of Julia Morrigan to the UN Special Committee on Decolonization, August

15, 1989, ETAN papers, McMaster University, file UNDC 1986–87.

[16] Canada Asia Working Group mandate review paper, 1993, Canada Asia Working Group papers (CAWG), private collection, Toronto, vol. G-6, file 33. For details see Webster (2020) and “Canadian Solidarity with East Timor: A history in images,” https://historybeyondborders.ca/?p=220.

[17] International NGO Forum on Indonesian Development record of meeting with Canadian delegation to Inter-Governmental Group on Indonesia, The Hague, June 17–18, 1988, Elaine Brière papers, private collection in author’s possession.

[18] “The Tragedy of East Timor,” McMaster University Archives, ETAN papers, vol. 10, file ETAN pamphlets.

[19] Note written in the margins of ETAN letter to C. Svoboda, UN Affairs Division, DEA, March 3, 1991, LAC, RG 25/26840/20-TIMOR[17].

[20] “The Right to Self-Determination of East Timor,” Brière presentation to UN Decolonization Committee on behalf of CAWG, August 12, 1988, CAWG G-3/19.

[21] Maria Braz, “East Timor: 460 Years of Resistance,” speech delivered on CNRM North America tour, 1993, http://foetca.blogspot.com/2015/11/cnrm-north-america-tour-1993-maria-braz.html.

[22] Mark Achbar and Peter Wintonick, directors, “Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky and the Media” (Canada, 1992), available for download at https://archive.org/details/dom-25409-manufacturingconsentnoamchomsk; ETAN Newsletter [1992], 10.

[23] APC history, https://www.apc.org/en/about/history.

[24] See David Webster, “The .tp country domain name, 1997-2015: In memoriam,” Active History, 16 March 2015, https://activehistory.ca/2015/03/the-tp-country-domain-name-1997-2015-in-memoriam/.

[25] “APCET’s message on its first anniversary,” Estafeta (APCET newsletter), May-June 1995, p. 7.

[26] “12 Nov. commemorated in Malaysia,” ETIN press release, 13 November 1992, PeaceNet collections; Sanusi Osman, “Press release on Conference on East Timor in Kuala Lumpur,” 9 Nov. 1996, PeaceNet collections; East Timor Update 34, 7 June 1994, https://timorarchive.ca/uploads/r/bishops/6/9/e/69e220adb7aa9998f7a44f3f649b523bba1f3522d1df53ae681e497609391338/ETU_June_1994.pdf; personal communications, Li-lien Gibbons.

[27] Clamor por Timor files, https://timorarchive.ca/clamor-por-timor; Timor Leste – Este País Quer Ser Livre (Clamor booklet, 1990s); research by Juliana Leal in São Paulo.

[28] José Ramos-Horta, Nobel Lecture, 10 December 1996 https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/1996/ramos-horta/lecture/.

[29] “Minister for Foreign Affairs to visit Indonesia and East Timor,” Irish Department of Foreign Affairs new release, 14 April 1999; Andrews letter to Canadian foreign minister Lloyd Axworthy, 19 April 1999, Canada Department of Foreign Affairs file 20-TIMOR, document in author’s possession; Sean Steele, “Lobbying the Irish presidency of the EU,” Timor Link, 6 October 1996.

[30] Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Trade / Comité permanent des affaires étrangères et du commerce international: Evidence, URL:http://www.ourcommons.ca/DocumentViewer/en/36-1/FAIT/meeting-83/evidence (archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6smvCzVWg); See also Webster (2020).

[31] Xanana letter to Lloyd Axworthy, 30 October 1998, Canada file 20-TIMOR.