The as-yet-unwritten histories of Australian solidarity/advocacy on Timor should include much more than a narrative of the various actors, their activities and their late-blooming successes. At the very least, these histories should also document and explore the difficulties, the internal debates and divisions, the failures. The present work offers a modest, if somewhat anecdotal, introduction to some of these latter issues.

This work is structured around some propositions drawn from the author’s observations and experience as a participant in Timor solidarity work in Australia in the decade starting in 1975. Where possible, the text is supplemented with available documentary material, but much more study is required to validate or contradict this author’s assertions.

In Australian Timor activist circles, the “solidarity” word is loosely applied to any individual or organisational activity supporting the East Timorese in their 1974-1999 struggles – be that for self-determination and/or national independence, for food, for justice, for simple human dignity.

For the purposes of this paper, “solidarity groups” are those which were created specifically to support East Timorese political self-determination and/or independence. They are distinguished here from pre-existing civil society organisations which, in addition to other activities, advocated in support of one or more aspects of the East Timorese struggle.

Proposition: Australian support for Timor was not the sole preserve of the solidarity groups

Australian solidarity groups were not the only pro-Timor actors in Australia. Timor solidarity group activities must always be seen in the context of a broader spectrum of Australian community awareness and advocacy on Timor. The report of Timor-Leste’s truth and reconciliation commission provides a brief overview of this mix (CAVR 2013). David Scott provides more details (Scott 2005), as does Peter Job (2021a). A partial guide to some of those actors includes:

Trade Unions

In the early post invasion years, some trades unions took direct action against Indonesian interests in Australia – most notably with bans on trade shipments between Australia and Indonesia. There was also early trade union interest in organising a hospital-ship and medical aid venture in post-invasion Timor, but while creating public interest, it never eventuated. The Australian Journalists Association lobbied continually for inquiries and justice for journalists murdered by Indonesian forces in 1975 – the Balibo Five and Roger East. Activists within unions succeeded in promoting pro-Timor resolutions through the union peak body, the Australian Council of Trade Unions. These resolutions received some media coverage and, while keeping the “Timor” word in the public eye, probably also strengthened the arm of the many pro-Timor rank and file members of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) to which many unions were affiliated.

Parliament/Parties/Politicians

Timor was rarely a central issue of concern in the national parliament and was never likely to determine national election outcomes. Nevertheless, sympathy for Timor among ordinary members of the ALP, its broader voting constituency and a vocal minority of Labor parliamentarians in Canberra ensured that Timor was regularly raised in the Australian Parliament. Smaller numbers of non-Labor politicians also expressed public concerns (Dunn 1983). The establishment and conduct of a formal Senate inquiry about East Timor and the controversial parliamentary delegation visit to Timor in 1983, combined with ongoing Labor Party internal tensions over formal Timor policy, engendered significant mainstream media coverage in the early 1980s.

Roman Catholic Church

The Jesuit-based, Mark Raper-led Asia Bureau Australia was probably the first Catholic organisation to be publicly concerned with Timor. Despite knowledge of East Timor’s significant Catholic population, senior hierarchy of the Australian Church kept their distance from the issue. Paradoxically, the Bishops’ Catholic Commission for Justice and Peace (CCJP) did take an interest in the Timor issue, circulating Timor information to a broader Church constituency. This activity, among other non-Timor matters, ultimately led to the dissolution of the CCJP in 1987 by the Bishops following pressure from conservative circles inside and outside the Church. Hierarchy support for Timor did emerge in the 1990s, but not before various religious congregations and lay-people began to engage the issue, notably through the Churches-focussed work of Christians in Solidarity with East Timor (CISET; started in Melbourne, 1983) (Woolfe 1988; Smythe 2004: 99-123).

Non-Government Organisations

Australian media reported local-branch statements of well-known organisations like Amnesty International and the International Commission of Jurists. Humanitarian aid and development organisations like Community Aid Abroad, Action for World Development and Australian Catholic Relief maintained an active interest in the Timor issue and kept their broader constituencies informed. All three agencies were key supporters of the Australian Council for Overseas Aid (ACFOA) Timor engagement.

Australian Council for Overseas Aid

ACFOA, the peak representative body for Australian humanitarian aid, development and human rights organisations played a major Timor advocacy role locally and internationally. ACFOA involvement began substantially in late 1975, initiating public meetings and humanitarian aid programs for post-civil-war Timor. ACFOA’s public Timor advocacy and influence expanded greatly with the employment of Pat Walsh, starting in 1979/80. Such was its rising Timor importance in the early 1980s, the authoritative Timor advocate, James (Jim) Dunn, concluded of ACFOA’s Timor Task Force: “It is a measure of their success that the issue has not been allowed to die in Australia” (Dunn 1983: 382).

Individuals

It is possible to identify a number of outstanding individuals who had a significant public impact on the Timor issue in the first decade. One such person is Jim Dunn.

A former Australian diplomat in Portuguese East Timor (Consul, 1962-64), this life-long public servant had a profound local and international impact on Timor’s public profile. Combining prior Timor and foreign affairs experience with analytical writing skills, he soon became an acknowledged authority on the issue (see Job 2020). Underwriting all his work was a simple, unvaried commitment to the principle of self-determination for the East Timorese. In retrospect, this author believes activists should have sought his counsel more – particularly on the dynamics of bureaucratic, parliamentary and international diplomacy processes.

Journalists/Media

In the pre-internet era, mainstream commercial print and electronic media were the dominant information sources for most people. What got published could become known; what was marginalised or ignored remained off the majority’s radar.

Australian mainstream media in the 1975-85 period largely reflected a politically conservative outlook. Exceptional in their generally liberal flavour were the Sydney Morning Herald, the Melbourne Age, the Canberra Times and the National Times newspapers (all four being part of the Fairfax media group at the time) and the publicly-owned Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC; radio and television). While the Fairfax papers and the ABC were not seen by a majority of the population, they were principal news sources for most politically-engaged Australians. In that sense they played a significant role in continuing public awareness.

Media analyst Rodney Tiffen accurately noted that Australian media coverage focussed much more on Australian political debate about Timor than on developments in the territory. He concluded that “for all their fickleness and superficiality… the [Australian] news media played an important, if erratic, role to counter the [Australian government’s diplomacy of deceit” (Tiffen 2001: 104).

Australian Solidarity Group Soup

Australian solidarity groups were persistent, ever-present “torch-bearers” for Timor, even if they were generally small and marginalised. Diverse in membership and styles and largely uncoordinated, they still played a role in keeping the Timor issue alive in Australia. With very little direct power in Australian politics, they were at their most effective when interacting with mainstream non-government actors.

The first Campaign for Independent East Timor (CIET) groups emerged in Sydney and Darwin in late 1974, arising from Denis Freney’s contacts that year with Fretilin. CIET groups formed in a number of other states during 1975, except in Western Australia where activists established Friends of East Timor. Melbourne’s CIET was superseded by the formation of the Australia East Timor Association (AETA) on 7 December 1975. A number of AETA groups were subsequently started in some other cities; Tasmanian activists created the Hobart East Timor Committee.

The principal themes underpinning early solidarity group activity were: (i) support for the East Timorese people in general and, usually, Fretilin in particular; (ii) increasing community awareness of the issue; (iii) opposing Australian government support for the Indonesian occupation; and (iv) gathering and circulating information.

Most activities undertaken by solidarity groups were essentially self-determined, based on knowledge of the situation inside Timor and party and government policies in Canberra. This knowledge was drawn largely from dedicated activist newsletters,[1] non-government organisation publications and mainstream media reportage. There was some coordination on policy, slogans and activities – agreed at occasional national activists conferences, especially during 1976-79. Generally, however, solidarity groups acted independently and their actions were determined by a usually-small core-group of activists in each group, the membership of which often changed over time.

Public demonstrations of support for Timor characterised early solidarity group activity. Early 1976 hopes that the “Timor movement” might emulate the massed public demonstrations of dissent from Australian government policy on the Vietnam war were never realised. From 1977 onwards, public Timor demonstration events were increasingly rare, attracting little media attention. The exception might be found in Darwin where restlessly creative activists like Rob Wesley-Smith regularly organised small but eye-catching public events – usually reported by local media but rarely at a national level.[2]

Other activities included petitions to Parliament, information stalls, letter-writing campaigns to governments and politicians, voter surveys during national elections, letters to newspapers, street theatre, fundraising for radio contact and Fretilin delegation tours, indoor public meetings and seminars, musical / film events, strategic disruptions of significant public events, community radio programs, newsletter and booklet publication and distribution.

The establishment and maintenance of Darwin-based radio communications with the Fretilin-led resistance, 1976-78 and 1985, was profoundly important for East Timor and the outside world. While Australian solidarity groups used the public information gleaned from Fretilin communications from Timor, and contributed to fundraising campaigns to support the radio link, the operation was not collectively controlled by formal Australian solidarity groups.

Proposition: Solidarity / Advocacy for Timor in Australia was not initiated, directed or controlled by Fretilin

Most Australian solidarity groups and activists in the first decade “recognised” or at least acknowledged Fretilin as the leading entity in the East Timorese struggle for independence. Initial post-invasion relationships between solidarity activists and Fretilin were intense. Those involved in running the two-way radio link with Timor, 1976-78, were in constant contact with Fretilin inside and outside Timor. Less well-known is the early assistance given by a number of Australians to José Ramos-Horta in his ever-challenging diplomatic responsibilities at the United Nations in New York.

Visits to Australia during 1976 by Fretilin’s external delegation members offered opportunities for public meetings and private exchanges of information – but these ceased when the Fraser Government banned such visits later that year. Delegation visits to Australia resumed only in mid-1983 with the election of the Bob Hawke Labor Government. Communications between solidarity groups and the external delegation – usually by physical mail, and rarely by telecommunications of any type in the pre-internet era – most often concerned prospects for annual non-government petitioning at the UN.

Some specific solidarity group actions may have arisen directly from suggestions or requests from external delegation members – especially José Ramos-Horta who was the most frequent contact – but most solidarity group activity was essentially self-determined. While solidarity groups saw themselves generally supporting Fretilin, they never felt directed or controlled by it.

The only exception to this general statement might be found in an examination of the very close, complex working relationship between Denis Freney and certain members of Fretilin’s external delegation (see Scott 2005, Tanter 2022).

Proposition: Solidarity group work didn’t contribute much to mainstream media coverage of the Timor issue. Or did it?

Mainstream news media coverage on the East Timor issue in the 1975-85 period was likely more intensive in Australia than anywhere else. Most print media carried extensive reportage in the months leading up to, and following, the invasion. Over time reportage on actual events inside Timor diminished, rising again briefly to cover particular news events such as the 1978/9 war-induced famine. Generally, more attention was given to the public debate on government and party policies, especially that of the Australian Labor Party (Tiffen 2001; Gunn 1994).

A quick survey of solidarity group newsclip archives in Melbourne and online sets of the Canberra Times for the period 1976-1985[3] confirmed the author’s memory of few solidarity group statements or actions being reported by mainstream media. It may, however, be too simplistic to conclude that those groups had very little impact on media reportage. One notable event was the successful activist attempts to influence the development of the Australian Labor Party’s official position on Timor.

ALP Timor policy was a focus of media attention – especially before and after the 1983 election of the Bob Hawke Labor government. Prior to 1983, the ALP had adopted a strong resolution on Timor – too strong for the Hawke government which then devoted much energy to avoid it until it was watered down in 1984. The conflicts arising between ALP policy and Hawke government statements and actions provided ample news-fodder, thus keeping the Timor issue in the public eye. Rarely if ever mentioned, however, was the fact that the policy wording was essentially drafted by Timor activists in 1981-82. It was fed into the ALP policy development process via sympathetic rank-and-file Labor Party members and finally adopted by the party’s National Conference. Extensive media coverage on the subsequent Hawke Government’s management of the Timor issue can reasonably be attributed to the earlier “backroom” lobbying work of activists.[4]

Proposition: Explicit support for Fretilin was a dividing issue but not a substantial one within the solidarity groups

The public portrayal of Fretilin as “communist” by Indonesian Government figures increased markedly through 1975. This label – somewhat equivalent in 1970s Australia to the early-21st century’s “terrorist” – was publicly amplified by a small number of conservative elements in Australia. The label was also carried to Australia by anti-Fretilin refugees from the August/September 1975 civil war. These factors, given added credence by Fretilin’s “revolutionary” name and rhetoric, carried considerable traction for politically conservative Australians and hence posed problems for activist drives for general community support for Timor.

The “communist” label clearly was no problem for Timor solidarity activists who were Australian communists and non-party “fellow-travellers”. The most obvious sign of concern about the negative power of the label is the frequency with which some Timor supporters – solidarity groups not dominated by CPA members and most “mainstream” advocates – asserted and explained that Fretilin “was not communist” (this was technically correct until sometime in 1977 and certifiably incorrect from 1981, but Fretilin’s formal adoption of “Marxism-Leninism” was unknown to almost all activists until the 1990s).

This concern likely explains the early currents within solidarity groups on whether or not to explicitly recognise or support Fretilin. The author recalls the foundation meeting of Melbourne’s Australia East Timor Association on 7 December 1975 at which some reservations were expressed about AETA enshrining its foundation in explicit support for Fretilin. The meeting’s majority managed the reservations with the formulation: “AETA recognises the Democratic Republic of East Timor as initiated by Fretilin.”

CIET’s Denis Freney, strongly committed to Fretilin, was the most visible proponent of formal statements of “solidarity with Fretilin”. He is remembered by the author as an assertive, sometimes dominant presence at national solidarity group meetings through 1976-79, and the driving force behind the slogan. In late 1977 Freney circulated a challenge to murmurings against support for Fretilin following Francisco Xavier do Amaral’s expulsion from his positions in Fretilin and the RDTL government.[5] The decisions of the May 1978 national conference of solidarity groups includes the text of a resolution, proposed by CIET/Freney and adopted by the meeting: “to campaign for recognition by the United Nations of Fretilin as the sole, legitimate representative of the ET people and for (the) Australian Government to support such recognition” (emphasis added).[6]

Such a statement probably represents the high point of Australian solidarity-group statements in support of FRETILIN. The author recalls continuing private reservations about it within Melbourne AETA’s membership and among Timor-supporting individuals outside the solidarity groups. Few if any were prepared to make the effort to challenge or oppose it publicly – perhaps because they shared an understanding that most solidarity group activities in Australia at that time, CIET and non-CIET, could be conducted without specific reference to Fretilin’s assertions of its status.

Proposition: Resistance radio contact was a profound solidarity activity, but was contentious too

The 1976-1978 conduct of covert radio communications with the Fretilin-led East Timorese armed resistance is the best known and most discussed solidarity activity of the first decade.[7] Despite several Australian government attempts to sever the link, along with at least one feeble journalist/intelligence disinformation attempt to portray the link as a fictitious creation of Darwin activists (Cranston 1976), radio contact was lost only after the defection/capture of Fretilin’s Alarico Fernandes to Indonesia in late 1978.

The radio link was nominally run by the CIET, but it was actually managed and controlled by a small group of Communist Party of Australia (CPA) members – Denis Freney in Sydney and other CPA colleagues, especially Brian Manning in Darwin (Freney 1991: 357-373; Aarons 2010: 276-284). CPA control was a concern among non-communist Timor activists who feared the CPA role would, in the eyes of Australian mainstream media, diminish the credibility of public information coming from Fretilin in Timor. There was also concern among individual political adversaries of the CPA that radio information might be censored or changed for political/ideological reasons.[8]

Whether these fears and concerns were justified remains a topic for new research. There are some indications of control over what information was released – for example the texts of Alarico Fernandes’ late-1978 “Saturno/Skylight” radio messages were never released – though whether the decisions were taken in Sydney or Maputo is not clear.[9] In retrospect, it is easy to see why any organisation tasked with conducting covert (illegal) two-way radio communications would seek to tightly control the operation – not least to reduce the risk of capture by Australian officials seeking to disrupt the communications. Strict controls were obviously also necessary for internal (usually coded) communications between Fretilin leaderships inside and outside occupied East Timor. More obviously problematic, however, was CPA control of the distribution of public information coming from Timor. Creating a formal, politically-neutral listening-post (legal under Australian law) and information distribution centre in Darwin could have allayed justifiable concerns. Whether the archival record shows such an idea was proposed by critics and/or considered by the CPA managers, remains to be explored.

Proposition: “Political” differences within groups may not be reflected in surviving archives – but they were debilitating and destructive

This section draws on the author’s recall of the earliest years of his membership of AETA in Melbourne where, arguably, intra-group differences were the most explicit. Any broader applicability to other Australian solidarity groups remains subject to research.

One reason for some Timor-activist opposition to the prominence of the CPA in early solidarity activity was the belief that its role diminished the credibility of the Timor issue in the eyes of politically “moderate” and conservative Australians and the majority of Australia’s political class. This view was dismissed by some CPA members as “red-baiting”. Similarly, some were disinclined to follow the CPA (and Fretilin) in explicitly framing their activities as actions against US/Western imperialism. A less-public reason came from the relatively few but active members of rival communist parties who had explicit ideological differences with the CPA. Particularly notable in Melbourne were members of various “Trotskyite” parties who sought to dilute CPA influence.

During AETA’s first year, 1976, much of the group’s activity was organised by an executive committee (first formally elected by the members in April 1976) plus a number of other committed individual activists. During the course of 1976 tensions between two informal groupings emerged – one centred around the inaugural Chairperson, Dr Bill Roberts (a confidante of the CPA’s Denis Freney in Sydney) and one centred on David Scott. The only substantial accounts of these tensions are Scott’s and Tanter’s accounts from their “side” of this unhappy divide (Scott 2005, Tanter 2022). These, along with Boughton’s tentative characterisation of the divide as “liberal solidarity” versus the “solidarity of international socialism,” provide starting points for much deeper exploration (Boughton et al. 2016).

This author’s initial perusal of formal AETA meeting records suggests few fragments of evidence of the divide were recorded.[10] With Roberts and Scott now deceased, an urgent oral history project is required to capture this and other aspects of early AETA from surviving participants. The author’s personal recall of this period is that these tensions were increasingly obvious, were debilitating in the emotional energy devoted to them and made continuing participation in AETA activities increasingly unattractive. The author consequently declined to participate in the late-1977 committee elections. Ironically, both Bill Roberts and David Scott also withdrew from direct participation in AETA at that time. In those same elections, the CPA members lost their positions on the committee and, while rejoining it on request of the executive, faded out of the group during 1978. In later years, one member of the “Scott group” portrayed the election results as the successful outcome of a deliberate strategy on the part of himself and others in AETA – a claim needing further primary research before it can be confirmed.

Proposition: The rise/fall/rise of solidarity group activity mirrored that of the Resistance

The intensity and focus of solidarity group activity waxed and waned in the decade under consideration here.

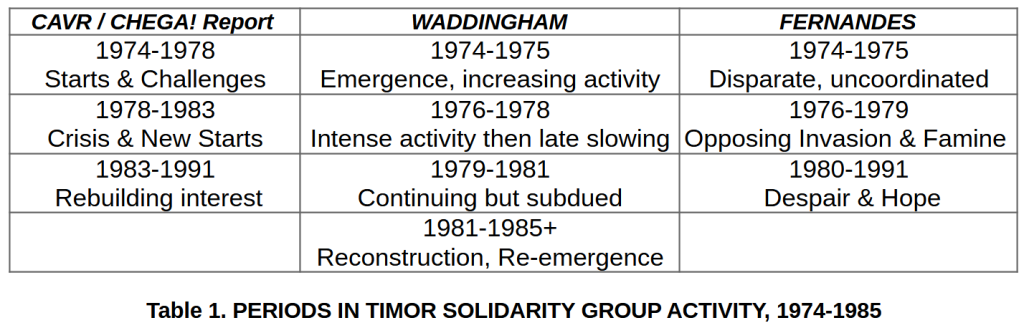

Timor-Leste’s 2005 truth and reconciliation commission report Chega! suggested three phases in solidarity activity in the first decade (CAVR 2013: 709ff). In a later website documenting Australian and international solidarity activity, Clinton Fernandes also discerned three phases over the same period.[11] Drawing on personal memory, the present author posits a four-phase scenario (see Table 1). Whatever the merit of such categorisations, they do point to a general conclusion that the nature and intensity of solidarity group activity, even over a relatively short period, was quite variable. The details and reasons for those variations are a valid focus for further research.

It is worth noting that this rise and fall in intensity somewhat mirrors what happened inside Timor in this period. Optimistic reports from Fretilin in 1976 and for most of 1977, describing successful resistance, were arguably supported by indirect evidence and sparse alternate sources. Late 1977 saw Fretilin’s internal divisions erupt into the open with the sacking of Xavier do Amaral and the intensification of Indonesian military actions. 1978 was marked by increasing awareness that the resistance was losing ground and the population was in serious trouble. The defection/capture of Alarico Fernandes, causing the loss of radio contact, and the hunting and killing of resistance hero Nicolau Lobato late that year were disastrous for resistance organisation and morale. Although known only to a few Australian “insiders”, there was also a serious rift within the Fretilin external delegation in the last months of 1978 (Scott 2005: 248-265).

With the exception of a resistance attack outside Dili in June 1980 and reports of new Indonesian military offensives in late 1981, little was heard outside Timor/Indonesia from the resistance until 1982/83. A major reorganisation of the resistance under Xanana Gusmão in March 1981 was not known by Fretilin’s external delegation, let alone solidarity activists, for another two years. That year, 1983, marked the start of increased information flows from inside Timor and an increasing international profile for the small but seemingly indestructible Xanana-led Timorese armed resistance.

There is a likely a partial link between perceptions of resistance decline in Timor and reduced activity in some solidarity groups in 1978/79. The author recalls his own sharp decline in personal optimism and productive output at this time – evident in no publication of his Timor Information Service newsletter between October 1978 and February 1980.[12] CIET’s East Timor News on the other hand continued publishing through 1979, but publication slowed in 1980.[13] A survey of Melbourne AETA’s meeting records up to 1980 noted very few formal minutes for the 1979-80 period.[14] The author recalls his part in an upsurge in AETA activity in Melbourne in 1981/82 – especially lobbying for a parliamentary inquiry on Timor and strengthening the Labor Party’s Timor policy. The initiative for both these activities, however, emerged from ACFOA’s Timor office in Melbourne. More study is needed to properly understand the re-intensification of solidarity group activity in the early 1980s. The 1983 election of the Hawke Labor government certainly stimulated increased solidarity work from that year onwards.

Writing the History of Timor Solidarity / Advocacy in Australia

The increasing number of available or emerging archival collections of Australian Timor-support organisations and individuals sets the stage for detailed histories to be written. David Scott’s book, specifically about Timor, remains the only monograph covering in any detail the time period of the present work (Scott 2005). Shorter-form accounts of aspects of Australian Timor solidarity in this period need critical scrutiny and extension, including Jolliffe (1976), Hill (1976), Freney (1979), Fernandes (2011) and Job (2021b). With the death of many first-generation activists, supplementing archives with oral interviews of surviving actors is essential.

The present paper attempts to point to some of the questions and issues to explore. Future generations will find more value in histories which focus less on the sense of triumphalism that pervades some Timor solidarity activist talk and more on the difficulties of the work. This author, for one, cares little for any “cosy blanket of half-remembering and convenient forgetting” (Andress 2018).

References

[1] See TiSA (Timor International Solidarity Archive), “Newsletters – TiSA special collection” https://timorarchive.ca/spec-coll-newsletters.

[2] See Clinton Fernandes, “Companion to East Timor – The Dawn,” 2016, https://webarchive.nla.gov.au/awa/20160322210006/https://unsw.adfa.edu.au/school-of-humanities-and-social-sciences/timor-companion/dawn. See also CHART, “Wes: Timor archives of key Darwin activist.” Timor Archives, 2015, https://timorarchives.wordpress.com/2015/08/10/rws-archives/.

[3] See The Canberra Times, https://trove.nla.gov.au/search/advanced/category/newspapers?keyword=timor&date.from=1975-01-01&date.to=1985-12-31&l-title=11, viewed 30 November 2023.

[4] See CHART, “Australia’s new Labor government, March 1983.” Timor Archives, 2013, https://timorarchives.wordpress.com/2013/03/05/hawke-labor-march-1983/.

[5] CIET, “Discussion paper for CIET and AETA activists – should CIET/AETA support FRETILIN? Campaign for Independent East Timor.” 7 October 1977, p. 10-11, Timor Archives, https://timorarchives.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/ciet-1977-sep-nov-p.pdf.

[6] CIET, “National East Timor activists conference, held in Sydney May 13-14 1978 – summary of discussion and decisions, Campaign for Independent East Timor,” 1978, Timor Archives, https://timorarchives.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/ciet-1978-may-p.pdf.

[7] See CHART, “Resistance radio 1975-1978.” Timor Archives, 2016, https://timorarchives.wordpress.com/2016/04/21/resistance-radio-1975-1978/.

[8] See CIET (Campaign for Independent East Timor). “Confidential to CIET and AETA groups, Campaign for Independent East Timor”. 15 January 1976, p. 18-21. Timor Archives, https://timorarchives.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/ciet-1976-jan-p.pdf.

[9] CHART, “Operation Skylight, 1978: Unresolved questions.” Timor Archives, 2020, https://timorarchives.wordpress.com/2020/06/26/operation-skylight-1978-01/.

[10] Victoria University, “Australia East Timor Association donates archive to VU library special collections,” 2022, https://www.vu.edu.au/about-vu/news-events/news/australia-east-timor-association-donates-archive-to-vu-library-special-collections.

[11] See Clinton Fernandes, “Companion to East Timor – International solidarity,” 2016, https://webarchive.nla.gov.au/awa/20160316095328/https://unsw.adfa.edu.au/school-of-humanities-and-social-sciences/timor-companion/solidarity.

[12] See CHART, “Timor Information Service.” Timor Archives: Newsletters, 2010, https://chartperiodicals.wordpress.com/2010/08/31/tis/.

[13] See CHART, “East Timor News 1977-1985.” Timor Archives: Newsletters, 2010, https://chartperiodicals.wordpress.com/2010/09/01/etn/.

[14] Solly Marshall-Radcliffe, “Guide to the records of the Australia East Timor Association (Melbourne), 1975-1980,” Unpublished manuscript, November 2013.