Timor-Leste’s struggle for self-determination involved multiple actors campaigning on multiple fronts around the world. This chapter focuses the solidarity movement’s campaigns to link Australia’s economic interest in oil and gas in the Timor Sea to Australia’s support for Indonesia’s invasion and occupation of Timor-Leste. It canvasses campaigns just prior to Indonesia’s invasion in 1975 that drew a nexus between Australia’s interest in hydrocarbons in the Timor Sea and Australia’s support for Indonesia’s invasion plans. This chapter surveys the efforts of solidarity activists to draw attention to the economic factors driving Australia’s support for Indonesia’s invasion and on-going occupation of East Timor in the 1970s and 80s and later efforts to use that interest as a pragmatic bargaining tool in the campaign for self-determination in 1990s.

Background

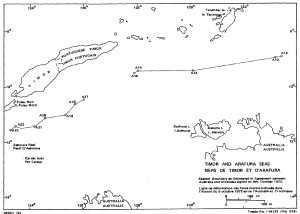

In 1963 the Australian Government secretly determined that Portuguese Timor would inevitably become part of Indonesia and that this would be in Australia’s national interest (McGrath 2017:28). That same year, Australia issued petroleum exploration permits north of the median line in the Timor Sea without consulting Portugal or Indonesia. In 1968, an American company, Oceanic Exploration, applied to Portugal for a petroleum exploration permit to the median line in the Timor Sea, over-lapping permits issued by Australia. Portugal made numerous approaches to Australia to negotiate a maritime boundary which were refused or rebuffed (Antunes 2003: 358). Instead, Australia negotiated seabed boundary treaties with Indonesia in 1971 and 1972 (McGrath 2017: 44, 53-7). The 1971 treaty was based on a median line. The 1972 Timor Sea Treaty, however, was extremely generous to Australia. It ran north of the median line, putting over 70 percent of the disputed area in Australia’s jurisdiction. The Timor Sea Treaty had a gap in the area between Australia and Portuguese Timor that became known as the “Timor gap”, see figure 1.[1]

In January 1974, Portugal issued a petroleum exploration permit to Oceanic Exploration triggering a diplomatic dispute with Australia over rights to hydrocarbons in the Timor Sea. This dispute was overshadowed in April when, after a change of government in Portugal, Portuguese Timor and all Portuguese colonies were put on the path to self-determination. An Australian Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA) brief on the likely future of Portuguese Timor recommended Australia not be “too active” on the issue as “media, both in Australia and overseas, could interpret this as evidence of our self-interest in the seabed boundary dispute rather than an objective concern for the future of Portuguese Timor”(Way 2000:54). This position became more entrenched following the discovery of a massive oil and gas field in disputed waters by Australian company Woodside in June 1974. Plans by Australian officials to negotiate with Portugal, potentially including Timorese representatives, were dropped after a meeting between Australian Prime Minister Gough Whitlam and Indonesian President Suharto in the first week of September, during which Whitlam secretly gave Suharto the green light to “incorporate” Portuguese Timor (McGrath 2017: 73; Way 2000: 111-12).

CIET and Fretilin expose Australia’s Timor Sea oil interests 1974–1979

In November 1974, Denis Freney, a journalist with the Communist Party newspaper, Tribune, formed the Sydney-based Campaign for an Independent East Timor (CIET) to support self-determination and independence (Freney 1975: 2). CIET supported the independence campaign of the Frente Revolucionária do Timor-Leste Independente/Revolutionary Front for an Independent East Timor (Fretilin). In January 1975, the União Democrática de Timor/Timorese Democratic Union, (UDT) dropped support for Portugal’s continuing involvement in the territory and formed a coalition with Fretilin campaigning for a transition to independence (Ramos-Horta 1996).

UDT leaders visited Australia in April 1975. On return to Portuguese Timor they abandoned Fretilin and joined forces with the Associação Popular Democrática Timorense/Popular Democratic Association of East Timor, APODETI, which supported integration with Indonesia (Ramos-Horta 1996). On 10 August, UDT sparked a civil war with Fretilin.

In an almost contemporaneous analysis, released on 20 September 1975, Freney alleged American and Australian oil companies encouraged UDT leaders during their visit to Australia to oppose independence and initiate the August coup (Freney 1975: 15). Freney’s discussion of the “propaganda war” in which Indonesia was “arming UDT and APODETI remnants” and seeking to “destabilise” Fretilin control to provide “an excuse for invasion” proved presciently correct, when, on Sunday 7 December 1975, 10,000 Indonesian troops invaded Portuguese Timor (Freney 1975: 54; Way 2000: 603).

Ten months after the invasion, Malcolm Fraser, prime minister in Australia’s Liberal/National Party coalition government, made his first official visit to Indonesia. John Reid, a director of Australia’s biggest mining company Broken Hill Propriety Company (BHP), was a member of Fraser’s delegation. Tribune observed that BHP would have been “particularly interested in Jakarta negotiations concerning the seabed border between Australia and East Timor” as the company had “recently obtained a controlling share of Woodside-Burmah and wants to recommence drilling […] off the East Timor coast”.[2] Indeed, while Fraser was in Jakarta, Australian and Indonesian officials met to negotiate a seabed boundary between Australia and East Timor, as reported on the front page of The Australian on 9 October 1976. The national daily paper related that the talks opened on October 8, with the aim to clear the way for Australian oil explorers in the area.[3]

Australia was forced to abandon the Timor Sea boundary talks in an early victory for the solidarity campaign, amid controversy about whether the talks required the Fraser Government’s formal recognition of East Timor’s integration into Indonesia (McGrath 2016: 289-90).[4] At the time, two forms of recognition were diplomatically understood in Australia. De jure sovereignty was the highest form of recognition meaning based on, or according to the law, and therefore meant a government accepted the validity of another government’s sovereignty. De facto was a lesser form of recognition, which acknowledged the fact that a state had effective control of a territory but not legal sovereignty. Australia voted in favour of a United Nations resolution in December 1975 calling on Indonesia to withdraw from East Timor and rejected Indonesia’s sham consultation process ceremony purporting to legitimise integration in mid-1976, which meant Australia had given neither de facto nor de jure recognition to Indonesia’s occupation of East Timor.

Fraser avoided directly addressing the issue in Indonesia, but the moment he was on the plane back to Australia, Indonesia’s Minister of State, Sudharmono, told media Fraser had accorded de facto recognition to East Timor’s integration by giving aid through the Indonesian Red Cross and shutting down Fretilin’s radio link in Darwin.

Fretilin information officer Chris Santos issued a statement alleging that by “participating in such talks the Australian Government has admitted Indonesian sovereignty over East Timor”, contradicting “statements by the Prime Minister that he did not recognise Indonesian claims to East Timor”. Under the headline, “PM Accused of “Illegal” Talks on Sea Border”, the Canberra Times quoted Santos saying it was “a fundamental principle of international law that seabed boundaries are determined between sovereign states”.[5]

The Suharto Government took the bait and embarrassed the Fraser government further, publicly stating that Indonesia “was prepared to negotiate a settlement of the disputed Australia-East Timor offshore border on terms that would be much more favourable to Australian interests than the Portuguese position”.[6] The Portuguese position was the median line in accordance with international law.

Fretilin’s intervention, pointing out that maritime boundary negotiations with Indonesia regarding waters between Australia and East Timor required not just de facto but de jure recognition, forced Australia to pull out of the seabed talks. Speaking at the UN two weeks later, Fretilin’s representative, Mari Alkatiri, denounced the October seabed talks as “adding up to recognition of Indonesian control of East Timor and a flagrant denial of the rights of the East Timorese people to decide about their national resources”.[7]

While Tribune may not have been widely read in mainstream Australia, it was required reading in sections of the DFA and among Australia’s intelligence agencies. The 24 November 1976 edition carried a story on “Australia’s role in the East Timor war” focussing on Australia’s economic interests in the Timor Sea and the cancelled maritime boundary talks. The article repeated Freney’s assertion that “multinational oil companies”, including the Woodside consortium, were “involved in the August 1975 coup by the reactionary UDT Party” and added that the same companies were “putting pressure on the Australian Government to accept this “tempting inducement” offered by the Indonesian generals who had already sold out their own nation’s interests in the area to Australian pressure”.[8]

Melbourne-based John Waddingham’s monthly newsletter, the Timor Information Service, similarly had regular readers in government.[9] The Timor Information Service October 1976 newsletter covered among other things, the controversy about Fraser’s de facto recognition, the Australian government’s seizure of a Fretilin radio, and the abandoned maritime boundary negotiations.[10]

CIET continued to monitor Australia’s Timor Sea activity. When the Western Australian government issued Pelsart Oil a petroleum exploration permit in April 1977 covering a large area north of the median line between Australia and occupied East Timor, CIET released a statement describing the decision as “an arrogant act to rob the East Timorese people of their birthright”.[11] CIET and other Timor solidarity groups sought urgent legal advice about an injunction to stop the government issuing the permit.[12]

On 20 January 1978, the Fraser government announced that Australia would give de facto recognition of Indonesia’s sovereignty in East Timor (Way et al. 2000: 839). The announcement was condemned by two members of the Government, the main opposition Australian Labor Party (ALP), the Catholic Commission for Justice and Peace, the Australian Journalists’ Association, the Australian Council for Overseas Aid and a range of East Timor solidarity groups (McGrath 2017: 124) The February 1978 edition of the Timor Information Service newsletter included a backgrounder on the Timor Sea dispute with maps and details of the resource companies holding permits.[13]

Unknown to activists, at the same time the Australian Government agreed to give de facto recognition, it also secretly decided to commence seabed boundary discussions with Indonesia (McGrath 2017: 120-22). Also unknown to activists, was the fact that government officials echoed Fretilin’s legal opinion that maritime boundary negotiations and resultant treaty required de jure recognition (Way et al. 2000: 839). Despite pressure from Indonesia and the permit holders, negotiations could not commence until the Fraser government took that step. Archival records show that throughout 1978, in addition to reports of atrocities in the public domain, the Australian government was regularly briefed on Indonesia’s brutal tactics to defeat Fretilin including deliberate mass starvation and the forcible relocation of tens of thousands of people into camps (Fernandes 2015). In response to the escalating death toll Australia escalated its efforts to keep the situation in East Timor out of the media in order to domestically justify announcing de jure recognition and start Timor Sea maritime boundary negotiations.

At a media conference in Canberra on 15 December 1978, Australia and Indonesia announced an agreement to commence negotiations to delimit the seabed boundaries between the two countries (Way et al. 2000: 840). Which, as Australia’s Foreign Minister Andrew Peacock explained, would “signify a de jure recognition by Australia of the incorporation of East Timor into Indonesia”. Negotiations to close the Timor gap began in early 1979.

The path to the Timor Gap Treaty – the policy fight within the ALP

The publication by Richard Walsh and George Munster in 1980 of a compilation of leaked classified documents, including 16 cables that Australia’s ambassador to Indonesia Richard Woolcott (March 1975 to March 1978) sent to Canberra in July and August 1975, offered the first indication from an official government source that the exploitation of oil and gas in the Timor gap area was a factor in Australia’s support for Indonesia’s invasion of Portuguese Timor (Munster and Walsh 1980).[14] Among the published cables was one from Woolcott to Canberra on 17 August 1975, in which he referred to the Department of Minerals and Energy’s “interest in closing the present gap in the agreed sea border”, which “could be much more readily negotiated with Indonesia […] than with Portugal or independent Portuguese Timor” (Munster and Walsh 1980: 200). Declassified archival records shows that this was just one of thousands of documents directly linking Australia’s Timor Sea economic interests to its foreign policy response to events in East Timor (McGrath 2017). It is unlikely this document would have ever been declassified if it had not been leaked.

In response to the leaked cables, Indonesia froze negotiations with Australia on maritime boundary negotiations with Australia to close the Timor gap.[15] The boundary was still unresolved when the ALP won the March 1983 federal election and Bob Hawke replaced Fraser as prime minister. It was ALP policy to not recognise Indonesian sovereignty in East Timor. This became problematic once in government as it meant the new government could not continue negotiations with Indonesia to close the Timor Gap.

In May, in the lead up to the ALP’s national conference in July 1984, an article in the TAPOL Bulletin, produced by the British Campaign for the Release of Indonesian Political Prisoners, examined the Timor Sea dispute and the conflict within the ALP, noting that Indonesia had “no right in the first place to be negotiating the boundary between East Timor and Australia”.[16]

Despite the efforts of activists within the left of the ALP, Hawke and his foreign minister Bill Hayden succeeded in passing a resolution at the party’s national conference in July 1984 that did not call for self-determination and was silent on the recognition issue (Davies 1991: 35). During a visit to Indonesia in August 1985, Hawke stated unequivocally, “We recognise the sovereign authority of Indonesia” (Davies 1991: 162). Portugal recalled its ambassador in Australia.[17] In a recorded message, resistance leader Xanana Gusmão told supporters that, “Bob Hawke’s hands are stained with the blood of the East Timorese” and linked the ALP’s “pragmatic” change of policy to the “extremely important fact of the current negotiations concerning the oil explorations of the Timor Gap” (Gusmão 2000).

No more blood for oil

Ten years after negotiations between Australia and Indonesia to close the Timor gap began, agreement was finally reached, not on a maritime boundary, but on a joint resource sharing arrangement. The treaty was infamously signed by Australia’s and Indonesia’s foreign ministers in a jet flying over the Timor Sea.[18] What is less well known, is that the ministers’ delegations were confronted by fifty protesters when they arrived in Darwin ahead of the jet ceremony, describing the treaty as “an act of piracy” and claiming the “area belonged to the people of East Timor”.[19] A delegation of East Timorese community leaders met with Australian foreign minister Gareth Evans and urged him not to sign the Treaty until there was a proper act of self-determination in East Timor. They argued “Australia’s position on Timor had always been hypocritical and that Australia had encouraged the Indonesian invasion in order to get access to oil in the Timor Sea, condemning the East Timorese people to extinction on the way”. Evans insisted “Australia’s recognition of Indonesian sovereignty had nothing to do with oil”.[20]

Portugal immediately wrote to the United Nations Secretary General noting that the ratification of such a treaty “will constitute a blatant breach of international law, namely of the relevant General Assembly and Security Council resolutions, since the Republic of Indonesia lacks the legitimacy to undertake any commitments regarding East Timor” (Krieger 1997: 360–61).

The Timor Gap Treaty prompted activists to launch the “No more blood for oil” campaign.[21] It also prompted Alfredo Pires, a Timorese refugee living in Melbourne, to march inside a barrel labelled “Timor’s oil” in the city’s annual street parade.[22]

The leader of Fretilin’s diplomatic campaign, José Ramos-Horta, warned that Australian oil companies that joined “in the violation of the Timorese maritime resources might see their licences revoked and the exploration and drilling rights transferred to American companies such as Oceanic Exploration” (Stepan 1990: iv). The March 1990 edition of Inside Indonesia published an analysis of the Timor Sea in which Andrews Mills (1990) concluded that Australia “placed much importance on the value of vast oil and gas resources in the Timor Gap’” The most comprehensive analysis of the dispute was published by the Australian Council for Overseas Aid (Stepan 1990).

Trinity College Oxford hosted a symposium on East Timor in December 1990 at which Distinguished Professor of Law at Rutgers University, Roger Clark, argued the 1989 Timor Gap Treaty was illegal (Clark 1992: 69). According to Clark, the “Australian Government had an international obligation not to recognize Indonesia’s forcible acquisition of the territory of East Timor” (Clark 1992: 88). Clark believed that “the principled position for Australia to take was to refuse to deal with the Indonesians, even if this meant that the boundaries of the continental shelf would not be delimited and the area in question would remain, for the foreseeable future, unexploited” (Clark 1992: 69).

In February 1991, Portugal instituted proceedings against Australia at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) challenging the 1989 Timor Gap Treaty. Portugal claimed Australia had failed to “observe the obligation to respect the duties and powers of Portugal as the Administering Power of East Timor and the right of the people of East Timor to self-determination” (Portugal v Australia). The case was highly embarrassing for Australia.

The Santa Cruz massacre in Dili on 12 November 1991 focused world attention on political dissent in East Timor. The massacre occurred a month before Australia and Indonesia were scheduled to announce the first round of successful bidders for Production Sharing Contracts under the illegal Timor Gap Treaty. The Australian Greens asked questions in the Senate about the appropriateness of signing an agreement with “Indonesia which will allow oil and gas exploration in the Timor Sea, […] only a month after the massacre in Dili?” (Vallentine 1991). Australia’s Foreign Minister Gareth Evans insisted the massacre was “the product of aberrant behaviour by a subgroup within the country”, and therefore it would be “utterly inappropriate […] to take any steps that would bring the bilateral relationship into disrepair” (Evans 1991).

The Santa Cruz massacre promoted US activists to form the East Timor Action Network (ETAN), described in Chris Lundry’s chapter. While ETAN initially focused on human rights abuses and East Timorese self-determination, it later led campaigns opposing Australia’s exploitation of Timorese assets in the Timor Sea.

In March 1992, Portugal escalated its Timor Sea campaign when a Portuguese car ferry the Lusitânia Expresso, arrived in Darwin on route to Dili to protest the Santa Cruz massacre. Portugal’s government-owned oil company, GALP Oil – also known as Petróleos de Portugal – helped finance the voyage. Australia and other western nations urged their citizens not to join the “peace mission”. Indonesia issued a statement declaring the territorial waters of Indonesia closed to the vessel because the proposed voyage was “provocative in nature” (Rothwell 1992).

While the primary goal of the student organisers was to focus world attention on Indonesia’s illegal occupation of East Timor, the voyage of the Lusitânia also drew world attention to Indonesia’s illegal occupation of the Timor Sea. After the ferry was forced to turn back by three Indonesian frigates, the Portuguese Government issued a statement noting that as “the United Nations does not recognise Jakarta’s rule and the territory is still officially under Portuguese administration, the Indonesian navy’s action was ‘illegitimate according to international law'”.[23] This in turn drew attention to Portugal’s ICJ challenge and to Australia and Indonesia’s carve up of sea off the coast of East Timor in the Timor Gap Treaty.

In 1994, before the ICJ case was decided, José Ramos-Horta and others unsuccessfully applied to the High Court of Australia to have the legislation giving effect to the Timor Gap Treaty declared invalid (HCA 1994). In 1995, the ICJ ruled in a majority verdict that it did not have jurisdiction to determine the matter due to Indonesia’s absence from the proceedings.[24] Regardless of the outcomes, both cases served to focus international attention on Australia’s economic interest in Timor Sea energy reserves.

In February 1994, a documentary by journalist John Pilger on the involvement of Western nations in the invasion and occupation of East Timor again focussed world attention on the Timor Gap Treaty. Pilger described the Timor Gap Treaty as “one of the biggest prizes for the west” as it allows “foreign companies to exploit the huge oil and gas reserves in the seabed off East Timor” (Documentary, Pilger and Munro 1994). Pilger’s documentary did nothing to shift Australia’s confidence that East Timor would remain a part of Indonesia. In October 1994, with the Timor Sea Treaty about to deliver economic dividends, Australia finally ratified UNCLOS.

In 1997, Australian petroleum engineer Geoffrey McKee became involved in East Timor’s campaign for independence. McKee had worked for one of the Timor Gap joint venture partners and believed that if the goal was independence, “you can’t get there by saying you are going to tear up the Timor Gap Treaty” (Fernandes 2011: 175). In a lengthy post to the ETAN mailing list, McKee argued that steps needed to be taken to assure the permit holders that their interests would not be threatened in the event of independence. His arguments appealed to Australian-based activists, Neil Sullivan, Juan Federer and Andrew McNaughtan. On 30 December 1997, they established a Timor Gap Advisory Committee (Fernandes 2011:175).

The resignation of President Suharto in May 1998 and subsequent shift in Indonesia’s Timor policy again focussed attention on Australia’s economic interests in the Timor Sea (Fernandes 2011: 33, McGrath 2020: 60-62).[25] It is well documented that Australia initially supported East Timor’s “autonomy” within Indonesia (Fernandes 2004: 25). Suharto’s successor B. J. Habibie, however, announced in January 1999 that Indonesia would allow a referendum on independence in East Timor. In an article in the Australian Financial Review, on 19 January, Australia’s former ambassador to Indonesia, Richard Woolcott, explicitly stated that a change in the status of East Timor could “lead to substantial financial implications for the Government if the Timor Gap Treaty, signed in 1989, were to unravel”.[26]

Woolcott was right. If East Timor remained part of Indonesia with a degree of autonomy, the Timor Gap Treaty would remain in force, but if East Timor became an independent state, the “clean slate doctrine” would apply meaning East Timor would be able “to determine whether or not it accepted the treaty obligations of Indonesia in relation to the Timor Gap Treaty”.[27]

UNTAET and Oceanic vs Australia

Australia put an enormous diplomatic effort into pushing the Timorese leadership and the United Nations Transitional Adminstration in East Timor to agree to continue the terms of the Timor Gap Treaty.[28] Given the humanitarian crisis and the challenges of establishing an independent state, Australia initially faced little opposition. In Darwin on 20 October, Gusmão, Alkatiri and Ramos-Horta signed a statement drafted by the DFA agreeing to “negotiate appropriate transition arrangements and consequent changes in the current Treaty that maintain its legal authority over petroleum resource development” (Collaery 2020: 209-10).[29] The following day the Australian military finally decided it was safe for Gusmão to return to East Timor (McGrath 2017: 164-65).

On 26 October, the day after UNTAET’s establishment, US oil company Phillips announced it was proceeding with the $US1.4 billion Bayu-Undan project citing the statement signed by “Mr Gusmão, Dr Ramos-Horta and Mr Alkatiri saying they would honour Timor gap petroleum zone arrangements”.[30]

In 1999, exiled Indonesian academic George Aditjondro published an analysis of the politics of oil relating to Timor in which he outlined the history of Australian oil exploration in Portuguese Timor before analysing the corporate structure of the multinational entities with Timor Sea permits, and detailing the influence of the “oil lobby” on the Whitlam and Fraser governments. Aditjondro argued that many Whitlam supporters “underestimated […] the strength of the oil lobby to convince the Prime Minister that it would be more beneficial for Australia to divide the revenues from the Timor Sea oil and gas with Indonesia, than to divide it with an independent East Timor” (Aditjondro 1999: 16).

On 10 February, UNTAET and Australia exchanged diplomatic notes to give effect to an agreement in which UNTAET replaced Indonesia as Australia’s partner in the 1989 Timor Gap Treaty with retrospective effect from 25 October 1999.[31]

In the April–June edition of Inside Indonesia, Geoff McKee argued that UNTAET did not have the power to “commit the East Timorese to any binding agreement”. The solution was “direct talks between Australia and a democratically constituted government of East Timor”, or failing that, “international arbitration” (McKee 2000).

Activists within the ALP worked with Opposition Foreign Affairs spokesperson Laurie Brereton to pass a pivotal resolution at the ALP National Conference in August 2000, stating Labor would “support the negotiation and conclusion of a permanent maritime boundary in the Timor Gap based on lines of equidistance between Australia and East Timor”.[32] The new ALP policy, reflecting principles set out in UNCLOS, meant that for the first time in decades, the two major political parties in Australia were not in lock step in pursuit of Timor Sea oil and gas north of the median line.

The main opposition to Australia’s campaign to reinstate the terms of Timor Gap Treaty came from US company Oceanic Exploration, which deployed staff to Dili to lobby UNTAET and inform “the public and the Timor-Leste Parliament about Timor Gap issues and reclaiming the 1974 Concession of Petrotimor including offering to negotiate the new Maritime boundaries” (Hasegawa 2013).

On 21 June, Oceanic’s claim to own a concession to exploit the Timor Gap was reported on Australian television. Galbraith told the ABC news program Lateline, that Oceanic claimed to be able to “redirect the gas pipeline to emerge in East Timor near the town of Suai instead of Darwin”.[33] On 26 June 2001 Oceanic announced it would lodge a statement of claim in the Australian Federal Court seeking legal recognition of the 1974 exploration concession granted by Portugal and that it would develop the Bayu Undan gas fields by building a pipeline to gas processing facilities in East Timor.[34] Oceanic’s media intervention and legal action in Australia did not delay the final round of Australia/UNTAET Timor Sea talks in Canberra on 28 June. The result was a massive win for Australia.

The Memorandum of Understanding of Timor Sea Arrangement was signed at a ceremony in Dili on 5 July 2001.[35] The Joint Petroleum Development Area was 100 percent on Timor-Leste’s side of the median line and the lateral boundaries were the same as those Australia negotiated with Indonesia. Australia’s one concession was to give UNTAET 90 percent of the royalties from the shared zone of exploration, compared to the 50-50 split Australia negotiated with the Suharto administration in 1989. The gas would be piped to Darwin. A side letter set out that Australia would pay East Timor AUD$8 million per annum for each year of the pipeline’s operation (Collaery 2020: 242-43).

Oceanic did not give up. In August the company filed a lawsuit in the Australian Federal Court against Phillips and the Indonesian and Australian governments, seeking US$1.5 billion in compensation for expropriated property rights. Throughout January and February 2002, Oceanic urged José Ramos-Horta and other Timorese leaders to drop the Timor Sea Arrangement and offered to fund an action at the ICJ (Munton 2006:195).

At a public forum on 23 March in Dili on East Timor’s maritime boundaries organised by Oceanic, company representative Neil Blue publicly offered to fund an ICJ case and indicated Oceanic had already “engaged the services of people who are major experts on the seabed issue”.[36]

The forum participants were unaware that two days earlier, on 21 March, Australia lodged declarations at the UN formally withdrawing consent to participate in any international maritime boundary related matters at the ICJ or the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea.[37]

On 9 April 2002, Darwin based Australians for Free East Timor released a leaked report on the Timor Sea maritime boundary by UNTAET’s senior economic adviser Ramiro Paz urging East Timor to urgently establish an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) boundary in the Timor Sea.[38] Paz argued that applying UNCLOS principles “three major oil fields now situated in the ill defined (and probably illegal) Australian seabed, would fall into East Timor’s newly defined EEZ”.[39]

Two days later, Professor Vaughan Lowe of Oxford University, Christopher Carleton of the UK Marine Hydrographic Office, and Sydney barrister Christopher Ward, provided their legal opinion on Timor-Leste’s maritime boundary rights to Oceanic. They advised that under UNLCOS, and applying modern principles of customary international the law, the new nation of Timor-Leste would be entitled to most or all of the area in the Timor Sea where the Greater Sunrise and Laminara oil and gas fields are located and all of the seabed north of the median line between Australia and Timor-Leste which would encompass 100% of the Bayu-Undan oil and gas field.[40]

On 19 May, the day before the ceremony marking the transfer of power from UNTAET to the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste, Australian Prime Minister John Howard, and Prime Minister-elect Mari Alkatiri were drowned out by protestors at the opening of the Australia-East Timor National Exhibition and Community Centre. Protestors held banners reading “Howard is a thief”, “Australia respect international law”, “John Howard enough is enough don’t steal our oil” and “Australia stop stealing Timor’s oil” (Documentary, McNaughtan 2002). The following day, Howard and Alkatiri signed the heads of agreement for the 2002 Timor Sea Treaty – the new nation’s first official act.[41]

Conclusion

The solidarity movement’s campaign to exploit Australia’s economic interest in energy resources in the Timor Sea became more sophisticated over the decades. It segued from calling out the economic factors driving Australia’s support for Indonesia’s invasion and ongoing occupation of East Timor in the 1970s and 80s to using that interest as a pragmatic bargaining tool in the campaign for self-determination in 1990s.

The success of the solidarity movement’s campaign can be gauged by Australia’s former ambassador to Indonesia Richard Woolcott’s comment in his 2003 autobiography that the claim “Australia had recognised Indonesian sovereignty over East Timor – because of our interest in oil reserves in the Timor Gap […] had gained public acceptance in Australia” (Woolcott 2003: 156).

Following Timor-Leste’s independence, the solidarity movement shifted gear to focus on the new nation’s rights under international law to a median line boundary in the Timor Sea. In 2004, La’o Hamutuk formed the Movement Against the Occupation of the Timor Sea in Dili and the Timor Sea Justice Campaign was launched in Melbourne. It was the revelation that Australia planted electronic listening devices in the room used by the Timor-Leste negotiating team during negotiations in 2004 that finally forced Australia to agree to participate in a UN Compulsory Conciliation that led to Australia agreeing to a permanent maritime boundary with Timor-Leste largely based on the median line.

References

[1] See Agreement between the Government of the Commonwealth of Australia and the Government of the Republic of Indonesia establishing Certain Seabed Boundaries, signed 18 May 1971, entered into force 8 November 1973; and Timor Sea Treaty, Agreement between the Government of the Commonwealth of Australia and the Government of the Republic of Indonesia establishing Certain Seabed Boundaries in the Area of the Timor and Arafura Seas, supplementary to the Agreement of 18 May 1971, signed 9 October 1972, entered into force, 8 November 1973.

[2] “Imperialism’s Stake in East Timor,” Tribune, 24 November 1976.

[3] “Now for Talks on Seabed Rights,” Australian, 9 October 1976.

[4] See also Gay Davidson, “PM’s new denial Timor views ‘unchanged’,” Canberra Times, 12 October 1976.

[5] See Frank Cranston, “Closer watch for Fretilin ‘pirate’ radios likely,” The Canberra Times, 4 October 1976; and “PM Accused of ‘Illegal’ Talks on Sea Border,” The Canberra Times, 18 October 1976.

[6] Michael Richardson, “Indonesia’s Timor Carrot,” Australian Financial Review, 19 October 1976.

[7] United Nations General Assembly 31: Fourth Committee: Item 25: Timor 1976, 3 November 1976.

[8] “Imperialism’s Stake in East Timor,” Tribune, 24 November 1976.

[9] John Waddingham managed the Melbourne-based Timor Information Service from 1975–1984 and from 2000 the Clearing House for Archival Records on Timor Project (CHART). All editions of the Timor Information Service are digitalised by CHART along with an important range of other newsletters published on East Timor’s struggle for independence, https://chartperiodicals.wordpress.com [accessed 29 January 2024].

[10] “Oil in Indonesia and East Timor – Australian interests,” Timor Information Service 4/15, October 1976.

[11] Campaign for an Independent East Timor, Media Statement, 11 May 1977, printed in East Timor News, No 7, 19 May 1977. See also John Arthur, “Parrys to search for oil in N-W,” Perth Daily, 20 April 1977; and John McIlwraith, “Timor oil rights dispute may severely embarrass Canberra,” Australian Financial Review, 15 May 1977.

[12] “Aust. Govt. & Oil Cos. Grab Timor Fields,” East Timor News 7, 19 May 1977.

[13] “Australia – East Timor sea-bed boundary dispute,” Timor Information Service, 23 February 1978.

[14] On 8 November 1980 the Fraser Government was granted an injunction banning publication of the book.

[15] See Laurie Oakes in The National Reporter 2(1), 14 January 1981.

[16] “The ‘Timor Gap’: Oil and Trouble,” TAPOL Bulletin, 16 May 1984.

[17] Hugh White, “Hawke shrugs off Portugal’s Timor protest,” Sydney Morning Herald, 23 August 1985.

[18] Timor Gap Treaty. Treaty between Australia and the Republic of Indonesia on the Zone of Cooperation in an Area between the Indonesian Province of East Timor and Northern Australia. Signed 11 December 1989; entered into force 9 February 1991.

[19] Ali Muklis, “Timor Gap deal brings together Australia, Indonesia,” Reuters, 11 December 1989.

[20] DFA, “Record of conversation between Senator Gareth Evans and East Timorese Community Leaders’, Darwin, 10 December 1989,” Arquivo & Museu da Resistência Timorense, Timor-Leste Resistance Archive and Museum, Dili. http://casacomum.org/cc/visualizador?pasta=06513.051#!1.

[21] Nick Everett, “No more blood for oil!” Green Left 162, October 12 1994. https://www.greenleft.org.au/content/no-more-blood-oil.

[22] When Alfredo Pires told me that story in 2013, he was Minister for Resources in the Gusmão Government.

[23] See Stephen Brown, “Portugal Condemns,” Reuters, Lisbon, 11 March 1992.

[24] See ICJ Reports, Portugal vs Australia, Case Concerning East Timor, 1995, in https://www.icj-cij.org/en/case/84/judgments.

[25] Mark Baker, “Downer ‘verges on racism’, says Horta,” The Sunday Age, 16 August 1998.

[26] Richard Woolcott, “It’s time to recall a treaty,” Australian Financial Review, 19 January 1999.

[27] Attorney-General’s Department, “Submission of the to the Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade References Committee, Inquiry into East Timor”, 19 April 1999: 3-5. Boundary treaties are an exception to the clean slate doctrine, however the Timor Gap Treaty was not a boundary treaty – it was a ‘provisional agreement’ allowing for exploration and exploitation of petroleum in the shared zone.

[28] UNTAET was established by UN Security Council Resolution 1272 (1999) adopted on 25 October 1999 (S/RES/1272, 1999). UNTAET was endowed with overall responsibility for the administration of East Timor and was empowered to exercise all legislative and executive authority, including the administration of justice. It governed the territory from 25 October 1999 to 30 April 2002.

[29] See Paul Tait, “East Timor backs gas project but warns on treaty,” Reuters, 10 November 1999.

[30] Idem.

[31] Exchange of Notes constituting an Agreement between the Government of Australia and the United Nations Transitional Administration in East Timor concerning the continued Operation of the Treaty between Australia and the Republic of Indonesia on the Zone of Cooperation in an Area between the Indonesian Province of East Timor and Northern Australia of 11 December 1989; signed 10 February 2000.

[32] Laurie Brereton, “Shadow Minister for Foreign Affairs, Media Statement, Labor Policy on the Future of the Timor Gap,” 3 August 2000.

[33] See Lynne Minion, “Timor Oil,” ABC Lateline, 21 June 2001; Philip Lasker, ABC Finance and Business News, 21 June 2001; and “US company claims rights to Timor Sea resources,” AAP, 21 June 2001.

[34] Jane Counsel, “Damages bid hits Timor Gap talks,” Sydney Morning Herald, 23 August 2001.

[35] Memorandum of Understanding of Timor Sea Arrangement: an understanding that will be suitable for adoption as an agreement between Australia and East Timor upon East Timor’s independence, embodying arrangements for the exploration and exploitation of the Joint Petroleum Development Area pending a final delimitation of the seabed between Australia and East Timor, signed 5 July 2001.

[36] Jill Jolliffe, “East Timor Oil Pact Row Stirs,” The Age, 26 March 2002.

[37] Australia Declaration of 21 March 2002 under articles 287 and 298 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

[38] See McKee, “Submission 87 to Joint Standing Committee on Treaties, Timor Sea Treaty”, 2002.

[39] See Ramiro V. Paz, ”Letter to Mari Alkatiri”, February 2001, https://www.laohamutuk.org/OilWeb/TSTreaty/Paz%20memo.htm

[40] Lowe, Vaughan, Christopher Carleton and Christopher Ward, “In the Matter of East Timor’s Maritime Boundaries Opinion,” 11 April 2002, Dili, Timor-Leste, https://www.laohamutuk.org/OilWeb/Company/PetroTim/LegalOp.htm

[41] Timor Sea Treaty. Between the Government of Australia and the Government of East Timor. Signed 20 May 2002; entered into force 2 April 2003.