The histories of African-Asian entanglements during the colonial period — connections which grew and extended through the common struggle against colonialism and the solidarity networks that were established between these peoples, particularly in the 1970s with the later decolonisation wave in Africa — are less accounted for in the national narrative and in the historiography of Timor-Leste. Despite some preliminary studies on the role of Portuguese-speaking African countries in the history of Timor-Leste (OPMT 2020; Tribess 2021; De Lucca 2021), there are few which focus on comprehensive research and analysis of this theme.

This chapter aims to address this absence, concerning Mozambique’s role in the history of international solidarity with Timor-Leste’s struggle for independence. Interweaving oral histories with archival research, the objective is to analyse the personal and collective trajectories and histories of connections between East Timorese and Mozambicans during the Indonesian occupation (1975-1999).[1]

The political, economical, and educational support from Mozambique to Timor-Leste’s independence, provided early on, determined that the external delegation would be established in Maputo during the Indonesian occupation of Timor-Leste. In the first decade of occupation, the support by the Portuguese-speaking African countries (PALOP) to the resolution voting initiatives at the UN assembly were crucial to keeping the Timor-Leste issue in UN agenda; also, the PALOP and, particularly Mozambique, brought Timor-Leste occupation to its bilateral diplomacy and to the debates at the Non-Aligned Movement, facing Indonesian and India’s opposition.[2]

Besides the Mozambican state support to Timor-Leste, the principle of solidarity with occupied people seeking refuge from different parts of the world dominated the personal and collective experience of Mozambicans, in periods marked by civil war, blockades and attacks from the apartheid regime allied forces, food rationing and hunger. The results from this research point to the existence of solidarity networks which are not limited to the government sphere, but which extend to all the Mozambican society.

This paper presents the results of research conducted between 2018 and 2023, which consisted in interviews with East Timorese and Mozambicans and archival research in Mozambique and Portugal. I interviewed Mozambicans engaged in the solidarity networks with Timor-Leste’s independence, policy makers and people who worked alongside the East Timorese in that period, and two major groups of Fretilin cadres: the individuals who constituted the external delegation in Mozambique and the group of students who were offered scholarships and support to continue their studies in the country.[3]

The oral histories of this dimension of the East Timorese independence movement include the testimonies of East Timorese who were on the move, often crossing several countries of diaspora. We cannot find these “archives” in buildings; however, they portray lives on the move, marked by arrivals and departures to different places and realities, where “ideas were formulated and reformulated” individually and collectively within the independence movement – they are “walking archives”. I borrow the concept of “walking archives” from Sónia Vaz Borges, which she uses to depict the “life trajectories, marked by errancy and itinerancy” referring to members of the liberation struggle in Guinea Bissau and Cape Verde led by PAIGC (African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde) (Borges 2019: 19-20).

From Timor-Leste, first stop in Portugal

A significant group of the East Timorese who went to live in Mozambique were initially studying at universities and technical schools in Portugal in the early seventies, with Portuguese government scholarships or the support of their families (a minority).[4] They were caught in the 25th April 1974 revolution and the intense political discussions and demonstrations which followed. University students were at the centre of the revolutionary tide and in 1974 and 1975 there were huge disruptions in classes, their courses were stopped, and scholarships suspended. A wide array of new political parties was being created, mostly left wing, and several East Timorese students affiliated and participated in their meetings.[5]

This group had regularly met at Casa de Timor, a place for meeting other East Timorese students and hold political discussions, although there was fear to speak openly due to censorship and the threat of arrest by the police, PIDE/DGS.[6] Other houses, such as Casa de Moçambique and Casa de Angola, were active in Coimbra and Lisboa since the forties.[7] After 25 April 1974, the group associated with ASDT and led by Vicente Reis “Sahe”, António Carvarinho “Mau Lear”, Hamis Bassarewan and Abílio Araújo “took over” Casa de Timor and renamed it Casa dos Timores, according to Marina Alkatiri and Filomena Almeida who were part of this group. The shift, according to them, signalled a stronger political awareness of an East Timorese identity freed from colonialism. Hence the name Timores, which carried the same meaning as Mauberes, the East Timorese who were not assimilated into the Portuguese culture, a term used by the Portuguese colonists to refer to East Timorese as inferior, and which was appropriated by the Timorese Social Democratic Association (ASDT) and then its successor Fretilin.[8]

Upon the arrival of José Ramos-Horta, Mari Alkatiri and Rogério Lobato in Lisbon on 7 December 1975, where they were met by Abílio Araújo and other members of the Comité de Acção Externa da FRETILIN (CAF) at the airport, they received the news of the Indonesian invasion. According to Marina Alkatiri, there was a heavy silence among the group, even though they knew the Indonesian troops were already inside the territory, this news came as a shock.[9] Finding no support from the Portuguese government, which was then in a state of constant crisis, and having identified Mozambique as a country willing to support Fretilin, the East Timorese took the decision to accept the offer from the Mozambican government and to set up Fretilin’s external representation in the country. In 1976, the students and CAF members joined the external delegation leaders Mari Alkatiri, Rogério Lobato, and José Luis Guterres in this move. José Ramos-Horta was sent to the United Nations to follow the Security Council vote in 1976. Roque Rodrigues was already in Maputo where he had established the external representation of Fretilin at the invitation of President Samora Machel, extended to Nicolau dos Reis Lobato when the Fretilin delegation visited the country for Mozambique’s proclamation of independence in June 1975.

There were, however, among the participants in the research East Timorese who had left Timor earlier to study in Portugal and who were not part CAF group in this period. Leonel Andrade, who studied Engineering at the University of Coimbra in the late sixties and later fled military conscription to Sweden as a refugee and Jorge Graça, who had lived with his Portuguese-East Timorese family in Mozambique in the sixties and went to study Law at the University of Lisboa in the early seventies, where he met António Carvarinho “Mau Lear”. They followed different paths, though they were active in political discussions based at Casa de Moçambique and visited Casa dos Timores a few times to take part in the cultural and political gatherings. Both had contacts with clandestine information networks and pro-democracy organisations in Europe (France, Germany and Sweden) who were supporting liberation movements in the Portuguese former colonies. Jorge Graça, in particular, took a role in the first Frelimo government as Deputy Director of Civil Service working with the Minister of State in the Presidency, Óscar Monteiro.[10] These are examples of different life trajectories, but who would later meet with the other Fretilin members in Mozambique.[11]

Support from Portuguese-speaking African nations and Mozambique

From 1975 onwards, the Portuguese former colonies in Africa gained independence while East Timorese aspirations for independence were stopped by a brutal Indonesian invasion and occupation. Nicolau dos Reis Lobato, sworn in as Prime Minister in the Fretilin government proclaimed days before the Indonesian invasion, had sent abroad José Ramos-Horta, Rogério Lobato and Mari Alkatiri to set up the external front of the resistance, knowing of the Indonesian forces already entering at the border and the imminent invasion.[12] Previous contacts with Frelimo were established by then the Vice-President Nicolau dos Reis Lobato in May 1975, when he visited Mozambique, Angola and Portugal.[13]

During the occupation period (1975-1999), the Portuguese-speaking African nations, which had just emerged as independent states in 1975, were the main moral and material supporters of the East Timorese struggle for independence.

The Mozambican party Frelimo, which has ruled the country since independence, provided support to the East Timorese Fretilin cadres who lived in Mozambique, particularly in university training, as well as in the political and economic support which it provided to the East Timorese resistance during their exile (Magalhães 2007: 502). Mozambique and Timor-Leste initiated, from 1975, an intense relationship of solidarity. Emblematic of this solidarity was the statement by Samora Machel, the first President of Mozambique, in a meeting with a Fretilin delegation[14] during the Mozambique’s independence ceremonies, which the East Timorese were invited to attend in June 1975: “while Timor-Leste is not an independent country, the independence of Mozambique will not be fulfilled”.[15] This was an axiom for the new Mozambican state, lead by Samora Machel, which was based in the principle of solidarity with all peoples oppressed by colonialism and economic imperialism.[16] Hence, the Frelimo government was effectively a “safe haven” to exiled left-wing political activists from Chile and Brazil and members of several liberation movements, in particular in Southern Africa: the ANC from South Africa, ZANU from Zimbabwe, SWAPO from Namibia. Earlier they had been solidary with the former colonies from Portugal, in particular Angola, through CONCP based in Rabat, first, and then Argel (Conferência das Organizações Nacionalistas das Colónias Portuguesas) (Monteiro 2001; Azevedo 2013).

Óscar Monteiro, Mozambique’s Minister of State in the Presidency at the time, who had been a Law student in Coimbra strongly engaged in the anti-dictatorship/liberation movements in the 1960s, provides a glimpse of this period. He tells the story of when he received a phone call from President Xavier do Amaral: “Comrade Monteiro, we are being invaded! Please help us!”[17] Monteiro ran to the Presidential palace, which was just across from his Ministry office and told the president what was happening. They called all the other members of CONCP, newly independent countries, to coordinate support. Eventually, he was designated by the President as responsible for the accommodation and support of the East Timorese in Mozambique, as well as other groups that Mozambique received in the country (ANC, Polisario Front, the Palestinians). Monteiro recalls that period:

Mozambique started to mobilize [diplomatic] contacts, but we received reluctant responses from some of them: the Muslim countries hesitated to confront the biggest Muslim country in the world and, on top of that, a prominent member of the Non-Aligned Movement and the host of the Bandung conference.

Soon after we received a message conveying the message that an East Timorese delegation would visit the country: Alkatiri, Ramos-Horta, Abílio Araújo, Guterres and Rogério Lobato. Nicolau had instructed them: the struggle will be long, and we don’t know how may of us will survive. You go abroad and spread the information to the world. They chose Mozambique as their external support base. We, with Angola, will be side by side with the East Timorese, without excuses, and in some of the most crucial moments, partnering with Portugal.[18]

In subsequent years, when Ramos-Horta attempted to gather support in keeping the issue of the Indonesian occupation of Timor in the agenda of the UN, the Portuguese-speaking African nations were instrumental in these efforts.[19] Ramos-Horta states that without the support of these countries the East Timorese case would have been dropped in 1975.[20] Their role in maintaining the Timorese question alive on the UN agenda during the eighties was paramount. They supported José Ramos-Horta, Mari Alkatiri, Abílio de Araújo and José Luís Guterres, the East Timorese who lobbied in the UN, when Portuguese diplomats were attempting to drop the case and US, Canada, Australia, Japan, the European countries, the ASEAN bloc and the Arab countries abstained from condemning the actions of Indonesia in the General Assembly yearly votes (Ramos-Horta 1996).

Mozambique, Angola and the other Portuguese-speaking African nations were also vocal at the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), where Indonesia played a prominent role. Their diplomatic action led to condemnatory resolutions against Indonesia occupation of Timor-Leste in Colombo, Sri Lanka, in 1976 and in Havana, Cuba, in 1979 (Gomes 2010: 71). Samora Machel raised the issue of Timor-Leste in his speeches and in press interviews at the summits and in the Harare summit, Zimbabwe, he opposed the Indonesian candidacy for NAM chairmanship (Gunn 1986: 9). The presence at UN as well as the NAM summits were by then important fora where Fretilin’s external front exerted pressure over Indonesia (Saute 1982).[21]

East Timorese in Mozambique

When the initial group of students arrive to join the external delegation leaders, the adaptation was easy, according to Filomena Almeida and Marina Alkatiri. The “use of Portuguese language and the warm way in which they were welcomed made them immediately feel at home”. According to them, the Fretilin’s external representation, which would become the first Embassy of the República Democrática de Timor-Leste, was treated as a state institution, and received funding directly from the Mozambican state budget. Initially this funding supported the students before they become government scholarship recipients at the University Eduardo Mondlane (UEM) and other universities and technical institutes; also, they were given houses.

Often students were also workers, to complement their scholarships and support their young children. Ana Pessoa, for example, told of her difficulties in doing her Law degree and at the same time working as a Law assistant at the Public Prosecutor’s service when her first child was born. Filomena Almeida, who also had a young child, was a Biology student at UEM and worked at the Wildlife and ecosystems department at the Ministry of Agriculture, where she participated in outreach campaigns for population awareness raising on the wildlife protection.[22]

The training of East Timorese cadres for the future independent country was a priority for the Mozambique president and this determination was shared with Fretilin’s leadership in the country.[23] From the sample of research participants there were East Timorese trained in Law, Agriculture, Veterinary Sciences, Biology, Medicine, Economics, Management, Engineering, and International Relations. There was freedom for the students to choose their courses and the government provided them with jobs in the areas of study.

Several East Timorese occupied positions in public institutions. Ana Pessoa was a judge and reached the office of Public Prosecutor, she also worked at the legislative reform team at the Ministry of Justice; Madalena Boavida was a public servant at the Ministry of Finance; Jorge Graça worked in the Office of the Minister of State in the Presidency in the first government of Mozambique, served in different capabilities in the state administration and law areas, and as a member of Parliament; Marina Alkatiri worked as a public servant Human Resource Management department, among others.

The Mozambique government also provided land for the group to farm and raise cattle: two properties (Machamba or Quinta da Matola and the Umbeluzi farm). This followed the socialist government principle of “fighting with our own means”, which aimed to instil the idea of self-sufficiency to the movements it supported. In the Umbeluzi farm, a fertile land near a river, the East Timorese agronomists, Isidoro Viana, Afonso Oliveira and Mário Alves, were able to plant crops, while Madalena Boavida, an economist, manage the farm earnings to support them during the harsh times of the civil war and the lack of food in the markets.[24]

Mozambique was a country facing several challenges, pressured by internal civil war and an external war, waged by the South African apartheid regime and Rhodesia (Monteiro 2001). All participants in the research spoke of the difficulties imposed by the civil war between Frelimo and Renamo, which were especially felt during the eighties, when the city of Maputo was under siege and travelling to other provinces of the country meant to put life in danger. Leonel Andrade was an Electrical Engineer working for the electricity state company and thus was called to repair power connections throughout the country, guarded by military columns.[25] José Soares, who was by then a trained doctor was called to attend the wounded in battle fronts. He recalls living this period and at the same time having no news about his family in Timor-Leste. He found out that his family was alive through an International Red Cross worker he met while doing this work and who was able to confirm that his parents were alive.[26]

Simultaneously, there was a long period when there were no connections to the interior of Timor-Leste, after the Radio was captured, it was especially hard to maintain a close coordination with the leadership in the interior of Timor-Leste. For most of the group, there was a sense that the life in Mozambique was lived in a very intense and “militant” way, in order to achieve personal, but also collective goals.[27] Ana Pessoa recalls that she worked night and day in the courts as a judge and as a Public Prosecutor, in Maputo and the Zambézia province. As Madalena Boavida reminisces, they were there on a mission, they represented a country and they had to correspond to all the trust and support that was given to them by the Mozambican government.[28]

In several of the interviews, there was a longing to return to their land, where their families were and who most of the students had said goodbye to their parents in the early seventies to study a couple of years in Portugal. Isidoro Viana recalls saying goodbye to their parents in Baucau airport in 1974 only to return in 2002 when it was finally safe to visit his village. In all those years he recalls having only once the possibility to send a letter, in 1986, to his parents through International Red Cross and even so the letter did not reach them due to the Indonesian control of information.[29] Some testimonies carry the heavy weight of guilt and some sense of displacement and lost time with close family, in a life where choices were imposed by the constraints of the war in Timor-Leste. They never imagined that their lives would change in such unexpected ways. Mozambique became a second country for most of them, some have Mozambican families now, who they brought to Timor-Leste.

Marina Alkatiri explained: “We were treated as Mozambicans”, however “we knew that we were being trained to go to Timor-Leste, this was our main objective”.[30]

Mozambican Memories of Solidarity with Timor-Leste

In the interviews and more informal conversations that I held with Mozambicans from several sectors of the society, who lived during the early period of the country’s independence, they shared memories of the solidarity with the independence cause in Timor-Leste. The support by the Mozambican government, led by the party Frelimo, but also by civil society organisations and individuals, was most evident when seen through a web of personal relationships that was established then.

At the time, with a wave of decolonisation of former colonies in Africa and Asia, in Mozambique there was solidarity among the population with all the oppressed people who were fighting for independence. Leonardo Simão, a Mozambican diplomat, who served as a Minister of Foreign Affairs (1994-2005) and Minister of Health (1986-1994), recalls the practical side of the Machel’s government principle of solidarity with all the oppressed people in the world: the Solidarity Bank. The Frelimo government encouraged all the Mozambicans to donate a percentage of their salary, corresponding to one day of work, to be given to independence movements and refugee groups, among them Fretilin.[31]

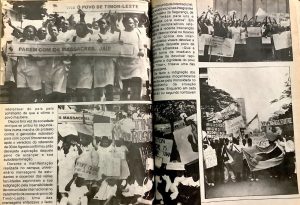

The support movements mobilized different groups in society — journalists, artists, academics and students, political refugees from other countries, mixed families — as well as common people who knew and worked with the East Timorese living in the country. According to Clara Soeiro,[32] a writer and actress in the Mozambican theater Tchova Xita Duma e Teum, she became an activist for the East Timorese cause as she thought it was an injustice that the East Timorese could not fulfill their right to self-determination. She and her husband, Etevaldo Hipólito, a Brazilian journalist, were involved in Amotil (Associação Moçambicana por Timor), a friendship association where Mozambicans and East Timorese joined in the organisation of cultural events and commemoration of symbolic dates, featuring East Timorese dances and food. AMOTIL played the important role of a support network and extended family throughout the years the East Timorese lived in Mozambique. They participated actively in the demonstrations and rallies in the streets of Maputo in 1991 and 1999 and in the submission of a petition to the Mozambican parliament in the 1990s demanding the condemnation of Indonesian atrocities in Timor.

On other spaces of the Mozambican society, such as the Universidade Eduardo Mondlane, the historian and lecturer Marlino Mubai[33] told of his experience as the head of university student’s movement at Faculty of Arts at UEM in the 90s, when they organised demonstrations to protest the Santa Cruz massacre in Dili and at the time of the 1999 referendum. He underlined the strong mobilisation of the student community around the East Timorese independence cause. He said it could be explained by the strength of the movement in that period, the presence of East Timorese students and lecturers in the university, the media coverage and the rector at the time, Prof. Fernando Ganhão, who was very supportive of the East Timorese cause.

Isabel Casimiro, a sociologist and professor at UEM, worked with Ana Pessoa in the organisation WILSA (Women and Law in Southern Africa Research and Education Trust) and at the Center for African Studies at the university. Both were founding members of this regional non-profit organisation that has been doing research and advocacy on women’s rights in the seven countries of Southern Africa. She talked of her memories of working together with Ana Pessoa and other Mozambican women, travelling to countries in Southern Africa, and realising that their work was so necessary and pioneering at that point in time. She also has fond memories of visiting the East Timorese Machamba (Farm) and “eating rice wrapped in banana leaf” in their gatherings, joined by members of the Polisario Front, who were also regular visitors and friends.[34]

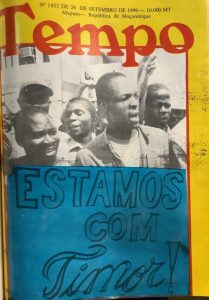

In the archives (National Historical Archives of Mozambique, National Library of Mozambique), through the print media coverage of the issue of Timor-Leste, it is possible to have a sense of the Mozambican interest and engagement with the independence struggle. The articles are more frequent between 1975-1985 and then again in the years of 1991 and 1999. I looked at the two main national publications: the daily newspaper Notícias and the weekly magazine Revista Tempo. The coverage intensifies in 1976, with the arrival of Fretilin’s external delegation in the country. The news covers important events such the UN Assembly voting sessions, Mozambique’s participation in the Non-Aligned Summits, the November 28th celebrations, the ongoing resistance fighting in the Timorese mountains, the economic and social situation and the human rights abuses in the territory. In 1999, during the lead up to the referendum and afterwards, there are detailed news and photographic coverage of the demonstrations and gatherings in support of the East Timorese independence.

This was possible through the work of journalists such as Alves Gomes[35] from the Revista Tempo who was dedicated to cover the Timor-Leste’s resistance in the late 1970s and early 80s. During this time, he was in close contact with East Timorese leaders of the external front in Mozambique and had direct access to the information they received from the armed resistance. The journalist explained the importance of the Tempo magazine, which was by then a major source of information of the Mozambican population and even used as an educational resource for learning Portuguese language.

As a result, in every corner of the country, people knew about the East Timorese struggle and that Mozambique was a then a major supporter. Tempo had a very wide national coverage, in a country with the size of 800.000 sq meters, but with a sparsely located population (almost 33 million).

Another news outlet, Radio Moçambique, which had an even wider reach, was also featuring news about Timor-Leste and the resistance movement, as well as covering major cultural events where the East Timorese participated.[36] Luis Loforte,[37] a journalist and head of Radio Mozambique’s program about music and culture from the 1970s up to 2000s, told that himself and other journalists felt compelled to advocate for Timor-Leste’s independence as much as Mozambique had also received support from other African nations in their struggle.

All these news outlets were closely affiliated with the government of Samora Machel, and the directors were appointed by the party in power, Frelimo. Nevertheless, according to Luis Loforte, he felt very free to choose the contents of the programs. Comparing that period with the journalism practised today in Mozambique, he asserted that they had more freedom, as they “did not have to respond to market-oriented priorities and were more interested in informing the public and transmitting knowledge about the world and the diverse cultures” in a newly established nation. Luis Loforte participated, along with other writers and theater artists, in events where poetry performance included readings of East Timorese poetry. Some of these events, Luis recalls, were broadcasted on the radio.

In the interviews and informal conversations with Mozambicans of the generations living in this period, including journalists and writers, the spirit of the time of solidarity with other people who were fighting for independence and against oppression was lived with intensity. This situation would change gradually as the country entered the 1990s and neoliberal reforms and institutions altered the previous political and social paradigms.

Conclusion

By providing a glimpse into the life trajectories of East Timorese who lived in Mozambique during the Indonesian occupation and their connections with Mozambicans, it is possible to address the lesser-known narratives in the country’s official historical account and inquire about the cosmopolitan dimension of the East Timorese society and history.

The personal accounts tell of multiple, rich experiences and intercultural connections which often followed unexpected paths, as these East Timorese lived through a dictatorial regime and witnessed a revolution in Portugal, followed the African and Asian liberation movements and, most importantly, experienced first-hand challenges of building an independent nation and state in Mozambique.

In carrying out this analysis of the solidarity relations between both countries it is crucial to know the Mozambican side of history, a newly independent country strongly engaged in the internationalist solidarity movement against colonialism and economic imperialism. During the period when Fretilin cadres lived in Mozambique, in the 1980s, the country was in a particularly difficult economic situation, carrying out a struggle to support the liberation movements in Southern Africa against the apartheid regime and its allies.

Despite these difficult times, it is possible to find several examples of how the Mozambican population was sympathetic with the East Timorese independence cause and how this support was not limited to the government and the Frelimo party, but it was equally present in Mozambican society, involving students, activists, a network of friends and family which was formed in those challenging years.

In conclusion, there is a cosmopolitan dimension of the East Timorese society and history that is often sidelined in favor of a supposedly more “indigenized” concept of East Timorese identity. However, East Timorese identities are built on long-term relations and lived experiences which connect them with other cultures, peoples and societies in different parts of the world.

References

[1] This chapter is an outcome of work carried out at the Centre for Social Studies, with the support of the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology, under the Multiannual Financing of R&D Units (UID/50012) and the research project “Transnational histories of solidarity in the south – researching ‘other’ knowledges and struggles for rights across the Indian Ocean” (2020-2026). It is an extended version of two published articles, with due authorisation of re-publication by the publisher (Gonçalves 2021a; Gonçalves 2021b).

[2] Interviews with José Ramos-Horta, Díli, 9 December 2019; and Leonardo Simão, Maputo, 8 November 2021.

[3] I interviewed a third group, the second generation of East Timorese who were born in Mozambique, though this group’s interviews will not be analysed in this article.

[4] In 1974 there were around forty students at universities in Portugal (Da Silva 2012: 61).

[5] Interviews with Ana Pessoa, Díli, 27 November 2019; Estanislau da Silva, Díli, 9 December 2019; José Soares, Maputo, 24 October 2019; Madalena Boavida, Díli, 12 December 2019; Marina Alkatiri e Filomena Almeida, Díli, 14 December 2019; Roque Rodrigues, Díli, 10 December 2019.

[6] International and State Defence Police/Directorate-General of Security.

[7] These associations were then grouped at the Casa dos Estudantes do Império (Association of the Students of the Empire,1944–1965) by the Portuguese authorities, where students from different Portuguese colonies organised political discussions. In spite of the police control, which led to its closure in 1965, this would be the centre for the African intellectuals who started the liberation movements (Castelo 2011).

[8] Interviews with Marina Alkatiri and Filomena Almeida, Díli, 14 December 2019.

[9] Idem.

[10] Interview with Jorge Graça, Díli, 24 November 2018.

[11] Interviews with Leonel Andrade, Maputo, 16 October 2019; Jorge Graça, Díli, 24 November 2018.

[12] Interviews with Mari Alkatiri, Díli, 11 December 2019; Roque Rodrigues, Díli, 10 December 2019.

[13] Interview with Roque Rodrigues, Díli, 10 December 2019.

[14] This delegation included Francisco Xavier do Amaral, Nicolau Lobato, Mari Alkatiri and Roque Rodrigues.

[15] Interview with Roque Rodrigues, Díli, 10 December 2019.

[16] Interviews with Joaquim Chissano, Maputo, 25 November 2021; Leonardo Simão, Maputo, 8 November 2021.

[17] Interview with Óscar Monteiro, Maputo, 5 November 2021.

[18] Óscar Monteiro, “Um Rio de Liberdades” (Unpublished manuscript, Maputo, 11 November 2021), 20–21. My own translation.

[19] Interviews with Mari Alkatiri, Díli, 11 December 2019; José Luis Guterres, Díli, 12 December 2019.

[20] Interview with José Ramos-Horta, Díli, 9 December 2019.

[21] António Saute, “Lutaremos Enquanto Existir o Povo Maubere (Entrevista a Mari Alkatiri),” Tempo [magazine], 11 April 1982.

[22] Interviews with Filomena Almeida and Marina Alkatiri, Díli, 11 December 2019.

[23] Interview with Mari Alkatiri, Díli, 11 December 2019.

[24] Interviews with Isidoro Viana, Díli, 14 November 2018; Afonso Oliveira, Díli, 17 November 2018; Mário Alves, Díli, 5 December 2019.

[25] Interview with Leonel Andrade, Maputo, 16 October 2019.

[26] Interview with José Soares, Maputo, 24 October 2019.

[27] Interview with Tomás Henriques, Díli, 14 December 2019.

[28] Interview with Madalena Boavida, Díli, 12 December 2019.

[29] Interview with Isidoro Viana, Díli, 14 November 2018.

[30] Interviews with Marina Alkatiri and Filomena Almeida, Díli, 14 December 2019.

[31] Interview with Leonardo Simão, Maputo, 8 November 2021.

[32] Interview with Clara Soeiro, Maputo, 20 November, 2021.

[33] Interview with Marlino Mubai, Maputo, 3 December, 2019.