In the fight against colonial oppression, international law is a weapon, alongside other forms of resistance by subjugated peoples. This was the case in East Timor, which freed itself from Indonesian rule.

At the time of its founding in 1991, IPJET had 100 registered jurists who were joined over the years by around 550 more nationals of 80 countries. As in all associations, only a part of IPJET members are truly active: however, at least a third of our membership has organized or participated in conferences and debates on the issues of Timor-Leste; wrote articles and book chapters; gave interviews in newspapers and other media; presented petitions at sessions of the UN Commission on Human Rights, the UN Special Political and Decolonization Committee and the Committee of 24; and lobbied their respective governments. The events described in this chapter are therefore just a part of IPJET’s work: because I experienced almost all of them, they are mostly narrated in the first person. I will focus on the most important events that our NGO organized or attended.

November 1991: The founding of IPJET

In 1991 a group of international lawyers decided to form an organisation to contribute to the end of East Timor’s foreign occupation by Indonesia. The group was stimulated by the independence of Eritrea and Namibia and positive developments in Western Sahara and South Africa. They officially formed the International Platform of Jurists for East Timor during a conference held in Lisbon from 8 to 10 November of 1991, which was attended by more than 60 jurists from 15 countries representing all continents.

It all started in Porto with a conversation with Sasha Stepan, an Australian jurist from Monash University who had written a thesis on the Timor Gap treaty. We thought it might be interesting to organize an association of jurists to help East Timor to be liberated. I do not know how our idea was passed on to other people, but we subsequently received three letters from individuals ready to help establish the platform: Rui Moura Ramos, Professor of International Private Law at the University of Coimbra; Paula Escarameia, then lecturer at the University of Macau; and José Manuel Pureza, then lecturer at Nova University Lisbon. Support from Professor Adriano Moreira was also essential: he won us not only the place for the constitutive conference, but also the support of the Assembly of the Republic of which he was a member. More than half of the funds needed to organize the conference came from the Portuguese Assembly of the Republic, another part from the Government and from several Portuguese and foreign institutions.

November 1991: IPJET’s reaction to the Santa Cruz massacre

On 12 November, two days after IPJET’s constitutive conference, James Dunn, former Australian Consul in Dili, Professors Roger Clark, of Rutgers Law School, and Garth Nettheim, of the University of New South Wales, and I were received by Portugal’s President, Mário Soares. During the meeting, his counsellor Carlos Gaspar entered the room with a worried expression. It was here that we learned of the Dili massacre. Everybody was in shock. Soares was very sad but quickly reacted by asking us to express our strong opposition to the United Nations against of that heinous crime. We subsequently sent a fax to Secretary-General Pérez de Cuéllar, undersigned by IPJET foreign founding members who were still in Portugal: James Dunn, Sasha Stepan, Garth Nettheim, Iain Scobbie and Roger Clark.

March 1992: Legal support to ‘Lusitania Expresso’: Activism on the high seas

In March 1992 Portuguese students linked with ‘Forum Estudante’ led by Rui Marques, a medical graduate, organised an event that had a significant impact in the media: a ferry, the ‘Lusitania Expresso’, with 120 persons of twenty-one nationalities on board, mainly Portuguese students and journalists, left Lisbon and after a stop in Darwin, sailed to Timor-Leste. The intention was to lay floral tributes on the tombs of those killed in the Santa Cruz cemetery in Dili. Former Portuguese President, General António Ramalho Eanes, was one of the guests. Several IPJET members were also on board, among them Shambhu Chopra, head of the Indian Society of Human Rights and president of IPJET; Ana Nunes, of the ‘Peace is Possible in East Timor’ group; and Professor António Barbedo de Magalhães, of the University of Porto.

In a moment of great tension, with military planes flying over the ferry at low altitude and Indonesian navy boats blocking the way, it was decided to turn back. A key factor in this decision was the issue of framing the situation within the rules of the law of the sea. In this regard, Shambhu Chopra gave legal advice to the organizers.

December 1992: IPJET’s first meeting outside Portugal

In December 1992, IPJET held its first meeting outside Portugal: in London. The conference was co-organised by CIIR, the Catholic Institute for International Relations, which organised for the conference to take place in the spectacular venue of the Law Society. Among the many participants were Shambhu Chopra, José Ramos-Horta, also a founding member of IPJET, Ana Gomes, who at the time was the first secretary of the Portuguese Embassy in London, and the late Lord Eric Avebury, a great supporter of the Timorese and Sahrawi causes, who founded the Parliamentary Human Rights Group. A memorable moment of the conference was when Ana Gomes completely dismantled the arguments of Peter Zoller, the envoy of the Australian Embassy. With the papers presented at the conference we published our first book, International Law and the Question of East Timor.

May 1993: A critical moment: The trial of Xanana Gusmão

When Indonesian forces arrested resistance leader Xanana Gusmão, the Indonesian Legal Aid Institute sent a letter to the commander of the Armed Forces stressing that the suspect should be entitled to counsel of his own choosing. The Legal Aid Institute subsequently received oral, and later written, power of attorney from members of Xanana’s family in Australia to represent him.

Indonesian authorities did not allow the Institute to represent Xanana. Instead, they allowed Sudjono, a prominent Jakarta attorney, to meet with Xanana in mid-December. According to Sudjono, Xanana had previously stated that he did not need legal representation until the trial itself, but that Sudjono was able to win his confidence over the course of four meetings. On January 26, Sudjono was officially appointed to represent Xanana.

Sudjono contacted IPJET asking for international law arguments that could help him in the defence. We exchanged some messages but suddenly the contact stopped. I assume that the Indonesian authorities thought that Sudjono was defending Xanana better than they wanted. My impression is that he disappeared as we were not able to contact him. Xanana spoke in his own defence in court, and he spoke very well.

Regardless, in May 1993, Xanana was tried, convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment under Article 108 of the Indonesian Penal Code (rebellion), Law no. 12 of 1951 (illegal possession of firearms) and Article 106 (attempting to separate part of the territory of Indonesia).

A few months later, IPJET’s International Council initiated an appeal addressed to the UN Secretary-General urging him to help obtain the immediate and unconditional release of Xanana Gusmão and of all other detained East Timorese. 1,873 legal professionals, government officials and public figures from around 40 countries signed. Among them were 50 parliamentarians, two former foreign ministers, diplomats, judges of Supreme Courts, bishops, heads of universities and law schools and leaders of more than 30 NGOs. IPJET’s Secretary handed these signatures to the Chairman of the UN Decolonization Committee on 13 July 1994. By the end of July, 573 more people had signed.

June 1993: IPJET at the World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna

Many IPJET members attended the World Conference on Human Rights that was held in Vienna in June 1993, both at the intergovernmental meetings and the NGO for a that ran parallel to the conference, including: the East Timorese José Ramos-Horta, the Sahrawi Omar Mansour (Head of the European Department of Polisario Front), the Moroccan Saddick Lahrach (Association Marocaine des Droits de l’Homme), the Egyptian Amir Salem (Director of the Legal Research and Resource Center for Human Rights), the Koreans Won Soon Park and Cho Yong Whan (Lawyers for a Democratic Society), the Australians Prof. Garth Nettheim (University of New South Wales) and Pat Walsh (Director of the Australian Council for Overseas Aid’s Human Rights Office), the Dutch Michael van Walt (General-Secretary of the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organisation), the Austrian Erwin Lanc (President of the International Institute for Peace), the Nepalese Gopal Siwakoti (Executive Director of Inhured International), the British Prof. Christine Chinkin (University of Southampton) and Catherine Scott (CIIR), the Colombian Magda Gonzalez (FEDEFAM), the Kashmirs Syed Gilani (Secretary General of the Jammu and Kashmir Council for Human Rights) and Abdul Bhatti (lawyer in Rawalpindi, Pakistan) and the Portuguese Marta Santos Pais (Human Rights Expert at the Procuradoria Geral da República).

May/June 1994: The Asia-Pacific Conference on East Timor (APCET): An event reported around the world

The very influential Asia-Pacific Conference on East Timor was convened by Initiatives for International Dialogue (IID) and 14 other Philippine NGOs together with 13 international institutions, including IPJET. The conference took place at the University of the Philippines in Manila from May 31 – June 4. It tackled the legal, political and cultural dimensions of the East Timorese struggle. IPJET, together with LawAsia, was in charge of the legal issues. Although IID did the primary organising work, IPJET’s role was important. As the IID was expecting the Philippine government to be pressured by Indonesia, it thought that it would be better to present the conference as an initiative from outside. That is why I was invited by Gus Miclat, the executive director of IID, to help launch the conference. I stayed in Manila for a fortnight in March, participating in several debates at universities and also in press conferences for Philippine and international media.

(Photo credit: Time Asia)

Full coverage of this conference appears in Gus Miclat’s chapter in this volume, but I would like to add here some curious details that helped make this conference an incredible victory for the Timorese cause:

- the Philippine government blacklisted Danielle Miterrand, the wife of the French president, a few weeks before a state visit by the Philippine president to Paris; Danielle Miterrand called a press conference in protest;

- an immigration official cancelled the departures of ten foreign APCET delegates (among them, six IPJET members) and initiated deportation proceedings against them, but thanks to our local lawyers and the support of the media and public opinion the government felt compelled to back down;

- Mairead Maguire, Irish Nobel Peace Prize winner, was turned back at Manila airport, which caused Cardinal Sin to express disappointment over Maguire’s deportation and the banning of other foreign delegates from the conference;

- Bishop Aloysius Soma of Nagoya, whose name was removed from the blacklist after a protest by the Japanese government, arrived at the Conference amidst strong applause;

Thanks to all these episodes and related commotion APCET remained on the front pages of practically all newspapers of Manila for more than three weeks and was international news for many days: on television (from CNN to Mexican TV channels), on the radio (from BBC to the Dutch Wereldomroep), and on the press (from the Washington Post to the New York Times and Le Monde, from the International Herald Tribune to Time and Newsweek).

October 1994: The Conference of Iserlohn

Co-organised by IPJET, the University of Porto, the South East Asia Info Center (Bochum) and the Evangelische Academie Iserlohn, the Conference of Iserlohn in October 1994 presented an impressive panel including Rüdiger Sareika, Peter Franke, Clemens Ludwig and Rainer Kahrs, from Germany, the Ambassador of Portugal in Germany Pinto da França, the East Timorese José Ramos-Horta, Mari Alkatiri, Zacarias da Costa and José Amorim, Barbedo de Magalhães, from Portugal, Christine Chinkin and Max Stahl, from Britain, Roger Clark, from the United States, Gilmar Mendes, from Brazil, George Aditjondro, from Indonesia, Renato Constantino, from the Philippines and Ariffin Omar, from Malaysia.

Around 120 persons registered to attend the conference and others arrived at the last moment. Among the participants, five flew from Indonesia and six from the Philippines. The way the Timor occupation was perceived in Indonesia, and the events of APCET and their aftermath, were important issues at Iserlohn.

May/June 1995: The Inter-Parliamentary Conference on East Timor

The Inter-Parliamentary Conference on East Timor was hosted and organised by the Portuguese Parliament’s ad hoc Committee for the Question of East Timor in May/June 1995. It gathered around 80 parliamentarians from more than 30 countries from all continents and about 80 other participants (among them, 18 IPJET members). The meeting unanimously adopted an important declaration which included a 25-point Plan of Action and a decision to establish a permanent structure for the ‘Parliamentarians for East Timor’.

IPJET’s Secretary reported in a short intervention on the activities of the Platform and asked the jurists present to become members. Fifteen more participants (from Angola, Burma, Brazil, Finland, Japan, Mozambique, Portugal, São Tome and Principe, Uruguay and Vanuatu) answered that appeal. One was the famous Lúcio Lara, general secretary of the governing MPLA party at the time of Angola’s independence.

June 1995: IPJET and the East Timor case at the ICJ

Four IPJET members were part of the team that represented Portugal at the ICJ in June 1995: the late Miguel Galvão Teles, a Portuguese attorney; Paulo Canelas de Castro, then assistant professor in the Faculty of Law of the University of Coimbra; Iain Scobbie, then lecturer in the Faculty of Law of the University of Dundee; and Sasha Stepanova (formerly Stepan), who had moved from Australia and was already a lawyer in Prague.

I attended all the sessions of the oral phase of the process at the ICJ and saw how the Australian representatives presented their views. They were in an uncomfortable position on the substantive matters: the Court had ruled six years before against Australia in the Nauru Case, and Australia had raised the same main preliminary objection. Thus, the Australian counsels adopted a deliberately aggressive style: as in football, they chose attack as the best defence, and they succeeded. Basically, they argued that Portugal had no moral right to criticize Australia for violating international law by concluding a treaty with Indonesia to explore oil in the waters of Timor-Leste, when it was doing exactly the same, concluding agreements with Morocco to fish in the waters of Western Sahara.

On the 30 June the Court handed down a decision which accepted the Australian objection that a ruling on the merits would require it to determine the rights and obligations of Indonesia, and found – by a majority of 14 votes to 2 – that it could not exercise jurisdiction in the case. Importantly, however, it clearly reaffirmed the right of the East Timorese to self-determination. As Iain Scobbie noted in a comment to the Judgement, that ruling on self-determination was strictly unnecessary. It was in fact a gesture to the East Timorese because the consequence of the Court’s characterisation of self-determination – as a right erga omnes – was that such right was binding on all states, thus also on Indonesia.

July 1995: Four conferences in Australia

Four conferences on East Timor were held in Australia in 1995, at which there was a strong IPJET presence, which resulted in a large increase in members of our platform and many expressions of interest by eminent jurists.

The first conference I attended was ‘The United Nations: Between Sovereignty and Global Governance?’, which was held from 2-6 July at La Trobe University, Melbourne. This conference was presented as a commemoration of the UN’s 50th anniversary but in reality, it was part of a campaign to make Gareth Evans, the Australian Minister for Foreign Affairs, the next Secretary-General of the UN. The East Timor question was not one of the formal subjects of the conference. However, it was present at the plenary session and some of the workshops. Evans addressed the conference and was met with vocal demonstrations by East Timorese. The demonstrations and the publicity arising from them completely blocked the intentions of the organizers.

The next conference, ‘Peacemaking Initiatives for East Timor’, was held at the Australian National University from 10-12 July. It was marked by strong participation by East Timorese and courageous statements by Armindo Maia from the University of East Timor. I had already prepared a presentation for the conference, but as the ICJ published its decision in the East Timor case a few days before, I felt obliged to write another one, an analysis of the entire process.

The Australian Model United Nations Conference took place at the University of New South Wales from 12-16 July. One of the two cases run by the model International Court of Justice was the East Timor case. Two IPJET members, Professor Barbedo de Magalhães and I, gave speeches on the background of the problem.

The last event, from 25-28 July, was the Darwin Conference on Indonesia & Regional Conflict Resolution. This conference was organised by the very active Australian solidarity groups and was marked by the strong presence of Indonesian democrats.

November 1996: The Dublin Conference: The first participation of a foreign ruler in a conference on East Timor

In November 1996, the East Timor Ireland Solidarity Campaign and Porto University co-convened a conference titled, quite explicitly, ‘Europe’s Vital Role in a Solution to the East Timor Problem in Accordance with International Law’. The organizes chose Dublin due to the outstanding position of the Irish Government on the question, the existence of a very active solidarity group, and Ireland’s presidency of the European Union.

Joan Burton, the Irish Minister of State for Foreign Affairs, delivered the opening speech. It was the first time that a member of a European government outside Portugal participated in a solidarity conference on East Timor. Mário Soares, the former President of Portugal, sent a support message.

Keynote speakers were Nobel Peace Prize laureate Mairead Maguire; Justin Kilcullen, director of the NGO Trocaire; and Dick Roche, an Irish senator. A paper from Professor Noam Chomsky (USA) was read, as he was unable to be present. Other speakers included James Dunn, Roger Clark, Peter Finlay, Iain Scobbie, Catriona Drew, lecturer at the University of Glasgow, Gerry Simpson, lecturer at the Australian National University, Clive Symmons, research associate at Trinity College of Dublin, Gustavo Gabriel Lopez, a lawyer from Argentina, Akihisa Matsuno, an associate professor at the Osaka University of Foreign Studies, Ann Clwyd, a British MP, Hans Goran Franck, a Swedish lawyer and former MP, David Norris, an Irish senator, Eilis Ward, a political scientist at Trinity College, Kathleen Lynch, an Irish MP, Nico Warouw, international representative of the People’s Democratic Party of Indonesia, Paulette Pierson-Mathy, lecturer at the Université Libre de Bruxelles, Felipe Briones Vives, Public Prosecutor of Alicante, Peter Carey, professor at Oxford University, Nico Schulte Nordholt, lecturer at the University of Twente, and Angie Zelter, of Seeds of Hope; East Timor Ploughshares. Based on the papers presented at the conference, IPJET published its second book, The East Timor Problem and the Role of Europe.

December 1998: The Osaka Conference: A high point of activism

As expected, from the moment Indonesian president Suharto stepped down, many events concerning Timor-Leste took place. One of the main ones was the conference organized by Akihisa Matsuno at his Osaka University of Foreign Studies, with the collaboration of the Portuguese University of Aveiro. Matsuno had been a special member (that is, non-jurist) of IPJET for more than two years. He made an interesting presentation about the ‘Peoples Assembly in East Timor’ of May 1976, a fake meeting organized by the occupying power to try to convince the international community that the Timorese wanted integration into Indonesia. Coincidentally my presentation was also about false Indonesian arguments: those linked to the so-called “reintegration” of East Timor into Indonesia.

Three other special members of IPJET made presentations at the conference: the American Arnold Kohen, a well-known journalist and activist, José Grácio, professor of engineering at the University of Aveiro, and the Indonesian George Aditjondro, sociologist and anti-corruption activist. (Unfortunately, Grácio passed away in 2014 and Aditjondro two years later.)

One of the highlights was the intervention by Masamichi Kijima, a former imperial navy conscript who was in Dili during the Japanese occupation and who became a great activist for the Timorese cause.

January 1999: Conference on ‘Timorese Women and International Law’

The three-day conference, ‘Timorese Women and International Law’, was organised by IPJET and the Associação Portuguesa de Mulheres Juristas with the endorsement of the Fédération Internationale des Femmes de Carrière Juridique. It took place at the Salão Nobre of the Portuguese Parliament on 22 and 23 January, and on the last day it was held at the Conference Hall of the Feira das Indústrias de Lisboa. The conference stressed the particular position of women in East Timor under the Indonesian occupation.

It was opened by Almeida Santos, Chairman of the Portuguese Parliament, followed by deputy chairman Nuno Abecassis and the President of the Republic, Jorge Sampaio. Thirty-two speakers and moderators came from eighteen countries. Three were the keynote speakers: James Dunn, Ana Pessoa Pinto, member of the political committee of the National Council of Timorese Resistance, and Teresa Beleza, law professor at the University of Lisbon. The remaining twenty-nine included the aforementioned Paula Escarameia, José Alberto Azeredo Lopes, Sasha Stepan, Gustavo Gabriel Lopez, Shambhu Chopra and George Aditjondro; Miranda Sissons, from Yale University, Carmel Budiardjo, the founder of the NGO TAPOL, Sharon Scharfe, the Canadian secretary of Parliamentarians for East Timor, José Nascimento, a South African lawyer, Carmen Diaz-Llanos, head of the Spanish Association of Friends of Saharawi People, Patrícia Galvão Teles, a Portuguese international lawyer, Kiyoko Furusawa, lecturer on Development and Human Rights at the Keisen University in Tokyo, Anabela Atanásio, a Portuguese student at the University of London, José Antonio Rocamora, a Spanish historian, member of the Associación de Amigos de Timor, Joana Wilson, of ‘Seeds of Hope; East Timor Ploughshares’, Suzana Braz, a Portuguese human rights activist, Maureen Tolfree, sister of Brian Peters, one of the five journalists murdered in Balibó, Cláudia Caldeirinha. PhD Candidate at the European University Institute in Florence; and nine Timorese women, Emília Pires, of the East Timor Human Rights Centre, Fátima Guterres, former Secretary of the Timorese Armed Resistance, Ivette de Oliveira, of the Communication Forum of East Timorese Women, Gajah Mada University, Yogyakarta, Armandina Gusmão, from the occupied territory, Maria Domingas Alves and Dina Alves, from the Timorese Women’s Organisation, Bella Galhos, a refugee and activist in Canada, Maria Helena Pires, at that time Asia Office of the Catholic Institute for International Relations in London, and Pascoela Barreto, a sociologist.

The closing session had two speakers: Ambassador Fernando Neves, from the Portuguese Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Ambassador Frank Ruddy, mentioned above. Many of the speakers also referred to the issue of Western Sahara. But it was here that Frank Ruddy explained how the issues of Timor-Leste and Western Sahara were identical and criticized Portugal’s policy towards Western Sahara, a policy of double standards, words that Fernando Neves heard with his face flushed with embarrassment.

Three days after the end of the conference, Indonesian president B.J. Habibie announced that a referendum would be held in East Timor. Leaders of the Indonesian armed forces and Ali Alatas, the Foreign Minister, were against that decision, but had to accept it.

August/September 1999: IPJET observes the referendum

In the first week of August 1999, IPJET was accredited by UNAMET as a non-partisan observer mission of the consultation process. Nine IPJET members served as international observers. Four more people later signed up as members, including the Sahrawi Radhi Bachir, political adviser to the SADR president.

March 2002: IPJET and JSMP, the only foreign NGOs to observe the Jakarta sham trials

IPJET and the Judicial System Monitoring Programme (JSMP) cooperated in sending a legal observer to the East Timor trials before the Indonesian Ad Hoc Human Rights Court. Suzannah Linton, a specialist in international criminal law and human rights from Malaysia, represented IPJET. She sent detailed reports on each of the trial sessions, demonstrating that they were nothing but sham trials. In the end, based on those reports, she wrote an article about the judgments that I managed to get published in the magazine of the college where I studied, the Leiden Journal of International Law (Linton 2004).

Amnesty International, which had not sent any representatives to observe those trials, asked IPJET and JSMP to use our reports in their publications. Naturally, we were very pleased to obtain much greater publicity for our denunciation of the Indonesian ploy to prevent the creation of an ad hoc court to judge the crimes committed in Timor-Leste. In a joint press release of 15 August 2002, under the title ‘Indonesia: East Timor trials deliver neither truth nor justice’, JSMP and Amnesty International “expressed their grave disappointment in the trials of the first East Timor cases in Indonesia. The findings of the two organizations show that the trials were seriously flawed, have not been performed in accordance with international standards, and have delivered neither truth nor justice (…). In view of the serious problems with the trials in Jakarta, Amnesty International and JSMP believe that it is also the moment for UN to review its decision not to pursue the recommendations of its own International Commission of Inquiry on East Timor to establish an international criminal tribunal.”

May 2002: An unforgettable moment: The restoration of Timor-Leste’s independence

Needless to say, many IPJET members were present in Dili on the day Timor-Leste saw its independence restored. There is also no need to explain how we all felt when we saw the flag of the new country being raised. It was strange, but at the same time comforting, to see former US President Bill Clinton attending the ceremony in which UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan handed over the powers of UNTAET to the new government of Timor-Leste. We could not forget that the United States supported the illegal occupation of the territory until the last moment.

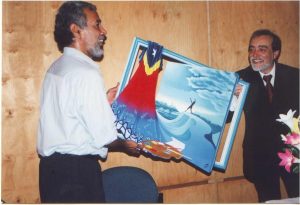

The following day I had the great pleasure of offering Xanana Gusmão, who had been elected honorary member of IPJET, a painting celebrating the restoration of the independence: “Independence” by Erik Kerkvliet.

March 2003: Alongside Ben Ferencz, in defence of The Hague and the International Criminal Court

It is known that the United States was against the creation of the International Criminal Court (ICC). President Barack Obama signed the Rome Statute, but did not submit it to Senate ratification. During the Bush administration, John Bolton (who was with us in defending the right to self-determination in Western Sahara) went even further. As the architect of American policy against the ICC, he created the so-called Article 98 bilateral agreements, through which countries that sign these agreements with the US agree not to surrender Americans to the jurisdiction of the ICC. Romania was the first country to sign it. Timor-Leste, unfortunately, was the third.

If that was not enough, the US House of Representatives and the Senate went even further: they enacted the ‘American Service-Members’ Protection Act’ (known by the nickname ‘the Hague Invasion Act’) which gives the president the right to send US forces to The Hague, should it attempt to bring an American to trial.

IPJET has always been a strong supporter of the creation of the ICC. It was one of the first NGOs that joined the NGO Coalition for the International Criminal Court (CICC) and its founding member, Paula Escarameia, played an extremely important role in the work that led to the creation of the court. Therefore, it is no wonder that we immediately joined the playful initiative taken by the Dutch NGO Hooghand: on the morning of the inauguration of the ICC in The Hague, prepared for a “military invasion”, dummy-soldiers from all the countries that were part of the ICC statute took up positions behind a row of sandbags at the beach of Scheveningen. It was an unforgettable ceremony: Benjamin Ferencz, the US Second World War veteran who worked as a prosecutor at the Nuremberg trials (and recently passed away at age of 103), gave an emotional speech, which ended with these words: “No one – not even the US – has the sovereign right to commit genocide.”

May 2015: IPJET is awarded the Order of Timor-Leste Medal

A memorable event in the life of IPJET was the awarding of the Medal of the Order of Timor-Leste by the then President Taur Matan Ruak. Some IPJET members had already been awarded the Order of Timor in previous years. Now it was our NGO’s turn, and as IPJET’s secretary, I represented it at the ceremony. The words that accompany the certificate, “for its contribution to the benefit of the Country, the Timorese and Humanity,” also had to do with the recognition of our struggle for the cause of Sahrawi people, a people that the Timorese consider as brothers.

May 2017: 25 years of IPJET

In May 2017 a conference was held to celebrate 25 years of IPJET. The conference took place in the Portuguese Assembly of the Republic and the Assembly also considered it as its own conference: it dealt with almost all logistical issues, printed and distributed a bilingual program, invited the ambassadors accredited in Lisbon and two of its vice presidents participated as speakers.

Jorge Lacão, Vice-President of the Assembly of the Republic, officially opened the event. The keynote speaker was Xanana Gusmão and the other speakers were Enhamed Khadad, Leonie Tanggahma, of the United Liberation Movement for West Papua, Gustavo Gabriel Lopez, Sisto dos Santos, coordinator of the HAK Association, from Timor-Leste, Cristina Cruz, from CIDAC, a Portuguese NGO, Joaquim da Fonseca, the Ambassador of Timor-Leste to the UK, Charles Scheiner, Roger Clark and Lauri Hannikainen.

Certainly the highlight of the conference was when Xanana Gusmão, holding the hand of Enhamed Khadad, the SADR coordinator with MINURSO, said out loud: “Western Sahara will win, as Timor-Leste also won!”

Rui Moura Ramos, José Manuel Pureza, International Law professor at the University of Coimbra, then Vice-President of the Assembly of the Republic, and I recalled the creation of the Platform and paid tribute to the memory of Professor Paula Escarameia and other late members.

A very sad note: three of the conference speakers, all of them great activists, have since passed away, Enhamed Khadad, in 2020, Leonie Tanggahma, in 2022, and Sisto dos Santos, in March 2024.

Conclusion

Over a quarter of a century, IPJET was able to contribute to resolving the East Timor question through networking globally, reminding audiences of the illegality of Indonesian rule, and helping to spread advocacy across international borders. This personal account has traced its work, which was not contained by one national space, but instead promoted East Timor as an international issue.