7 Contraception

STUDENT LEARNING OUTCOMES

At the end of this chapter you should be able to:

- Recall the key reasons that access to contraception is crucial for women

- Identify the reasons for unmet contraceptive needs

- Discuss Margaret Sanger’s involvement in the development of the birth control pill

- List the factors a woman should consider when deciding on a particular contraceptive method

- Discuss why there is no such thing as a perfect contraceptive method

- Compare and contrast the different methods of contraception

- Explain the difference between “perfect-use” and “typical-use” effectivity of methods

- Identify the different types of hormonal contraception and explain how they work

Unmet contraceptive needs represent a public health and social issue

The Oxford English dictionary defines contraception as the act of intentionally preventing pregnancy by employing devices, practices, medications, or surgery. It is also known as birth control. As noted in the 9th edition of the seminal text Our Bodies Ourselves written by the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective (2011) “our ability to prevent or delay pregnancy is fundamental to our ability to choose how we live our lives.” Access to contraception is crucial for women for many reasons and it is elemental to promoting empowerment and health. Why is it so crucial for women to access contraception?

Reasons why access to contraception is important for women

- Reproductive choice: Contraception provides women with the ability to plan their pregnancies and avoid unintended pregnancies.

- Educational and career opportunities: Contraception allows women to plan their lives so they may pursue higher education and professional career growth.

- Economic empowerment: By planning pregnancies women can improve their ability to manage resources and lessen the number of dependents to support until a time when they are more able.

- Health benefits: Contraception lowers mortality rates and some methods provide non-contraceptive health benefits such as controlling menstruation symptoms.

- Gender equity: Contraception provides autonomy and agency for women by empowering them to control their own reproductive lives.

- Poverty reduction: Contraception helps break the cycle of poverty by allowing women to control their family size. They are also more likely to take advantage of opportunities for themselves and their families.

A brief history of contraception

The first Western contraceptive measures were described in 3000 BCE as male penile sheaths (early condoms) made from animal bladders and intestines and in ancient China oil-lubed sheaths made from silk were used. In Japan, these early condoms were crafted from tortoise shells known as the Kabuta-Gata (Khan et al. 2013). While these primitive barriers reduced unwanted pregnancy their use was primarily for protection against sexually transmitted diseases. Vaginal poultices for contraception have been used by numerous cultures such as South American native women who inserted quinine-soaked bark strips into their vaginas (Pearson 1986).

In Innsbruck 1919, Ludwig Haberlandt conducted the first research that suggested exogenous hormonal control could be used as a contraceptive method thus paving the way for the development of oral contraceptives. Haberlandt produced infertile female rabbits by taking ovaries from pregnant rabbits and inserting them under the skin of the aforementioned female rabbits. He subsequently extracted copora lutea from pregnant cows and injected them into rabbits also resulting in infertile rabbits.

Unfortunately, the motivation to promote the scientific investigation of contraception in the United States was born from eugenics policies. Eugenics is a pseudoscience developed by Francis Galton in the early 1900s with a racial bias for wealthy, white-protestant individuals to reproduce over other lower-income, racial, and ethnic groups. Eugenics was a popular doctrine adopted by the American scientific community to oppress and negatively impact marginalized families. The strongest proponent of contraceptive research was Margaret Sangar (pictured on the right) who used the establishments’ embrace of eugenics to fuel support for the discovery of more effective and affordable contraception for women. In 1916 Sanger founded the first women’s birth control clinic that focused on women in poverty, empowering them to make their own reproductive choices. She understood that birth control was THE fundamental women’s rights issue writing that “forced motherhood is the most complete denial of a woman’s right to life and liberty”. Gloria Steinham (1998) was asked to comment on Sanger’s eugenics connection and found it to be a strategy, saying Sanger

adopted the mainstream eugenics language of the day, partly as a tactic, since many eugenicists opposed birth control on the grounds that the educated would use it more. Though her own work was directed toward voluntary birth control and public health programs, her use of eugenics language probably helped justify sterilization abuse. Her misjudgments should cause us to wonder what parallel errors we are making now and to question any tactics that fail to embody the ends we hope to achieve.

Women gained the potential for reproductive freedom thanks to Margaret Sanger’s efforts. In 1958, Pincus et al. reported the successful use of oral contraceptives as a means of birth control, and in 1960 the first oral hormonal contraceptive pill, Enovid, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), [see below for more information on clinical trials that led to the FDA’s approval]. Currently, approximately one-third of women worldwide use hormonal-action contraceptives (Anderson and Johnston 2023). Yet still, nearly half of the 210 million pregnancies that occur globally each year, are unintended (UN 2022). In the United States alone, a recent survey conducted by the CDC found the risk of unintended pregnancy of women aged 18-49 years is over 76% and over “60% of women had an ongoing or potential need for contraceptive services” (CDC 2021).

A biased oral contraceptive clinical trial was conducted in the US Territory of Puerto Rico.

First off, what is a clinical trial?

A clinical trial is defined as a study that compares the effect and value of intervention(s) against a control in human beings (Friedman, Furberg, and DeMets 2010). It is the best way to determine if a particular drug/treatment will work because the inclusion of a control group enables a direct comparison between using and not using the intervention. Ethical considerations arise during the design, implementation, and reporting of clinical trials. When considering a clinical trial, the following ethical criteria are essential: “value, scientific validity, fair selection of participants, favorable benefit/risk balance, independent review, informed consent, and respect for participants” (Friedman et al. 2010). Unfortunately the first clinical trials for oral contraceptives missed the mark on a few of these criterion.

The Puerto Rico Clinical Trial

Marks (Marks 2010) describes why women on the island of Puerto Rico were chosen for the large-scale oral contraceptive trial. There were big obstacles to setting up a clinical trial in Massachusetts (where initial small-scale research by Rock and Pincus had been conducted) which included legal restrictions on contraceptive research and an inability to find a large enough population of women willing to participate for the length of time needed. Puerto Rico seemed to be the perfect solution because several birth-control clinics were already established due to the combination of a high poverty rate exacerbated by the high birth rate and there were many willing participants. The study began in April 1956 with a total of 225 women, 125 of whom would serve in the control group using either conventional devices or no birth control. Over half of the participants left the trial for numerous reasons and were replaced with new volunteers and the study sites were expanded to Haiti and Mexico City.

The trial was biased from the start

The main benefactor of the birth control pill research was the staunch women’s rights advocate Katherine Dexter McCormick. She recognized the importance of conducting trials for the pill. However, according to Marks (2003) from the start her bias of equating participants as lab models rather than human beings, is evidenced in her comment to Dr. Pincus regarding the clinical trial bottleneck problem being “how to get a cage of ovulating females to experiment with”, written in a letter to Sanger in 1955. This attitude may have been shared by the lead researchers Pincus and Rock who did not provide full information to participants, withholding the fact that they were participating in a clinical trial in the first place, and were dismissive of their complaints of side effects saying they were “psychosomatic” because of the leading questions posed to participants. Their answer to the problem of large numbers of women dropping out of the trial was to ignore the issues and publish the results in terms of the number of menstrual cycles rather than individual women, thereby increasing the scale and making their results look more remarkable (Eig 2014).

Why don’t all sexually active women use protection?

Concerns about side effects as well as negative attitudes about pleasure, desire, and sex stop many from seeking information. On a wider scale, these attitudes keep sex information from being distributed freely in schools and community organizations. Even though, many studies show giving birth control information to teenagers does not make them more likely to have sex (Mark and Wu 2022).

Unintended pregnancies occur disproportionately in young and poor women and are associated with increased incidences of maternal and child mortality and cycles of intergenerational poverty (Bearak et al. 2022). Moreover, birth control is not just a women’s issue but societal messages neglect the impact that unprotected sex can have on men. It is also beneficial for men to be able to decide when and if they will father a child, as well as protect themselves from sexually transmitted infections.

Different methods of contraception

There are many types of contraception but none are perfect. The choice of which method to use comes down to multiple factors such as cost, ease of use, whether or not a physician is required for prescription/insertion, whether or not protection from sexually transmitted infections is sought as well, and potential side effects.

Methods can be divided into distinct categories based on their mode of action: fertility awareness methods, withdrawal, barrier methods, hormonal methods, IUDs, emergency contraception, and permanent methods. No method is 100% effective at preventing pregnancy but when used properly some are as high as 99% effective. Perfect efficacy of a method is only achieved when the method is correctly used each time and this rate is determined from clinical trials. Because people are not “perfect” each method is given a more realistic typical-use efficacy measure. This refers to the effectiveness of the method taking into account human error and is based upon real-world use. The following information about each type is from the Planned Parenthood website on birth control.

Withdrawal (Pulling Out)

Withdrawal refers to pulling the penis out of the vagina before ejaculation. If semen gets in the vagina, you can get pregnant. So ejaculating away from a vulva or vagina prevents pregnancy. But you have to be sure to pull out before any semen comes out, every single time you have vaginal sex, for it to work. This is challenging notes Arteaga and Gomez (2016), because it “requires men have somewhat precise control over and anticipation of ejaculation, as well as the wherewithal to remove the penis prior to sexual climax.” If done properly this method has a 78% Typical Use Efficacy. A study conducted by Jones et al., (2014) found that only a minority of withdrawal users (12% of the entire sample) relied on the method exclusively, and most had also used an additional highly effective method; this contraceptive method was most common among the youngest women surveyed.

Fertility awareness methods

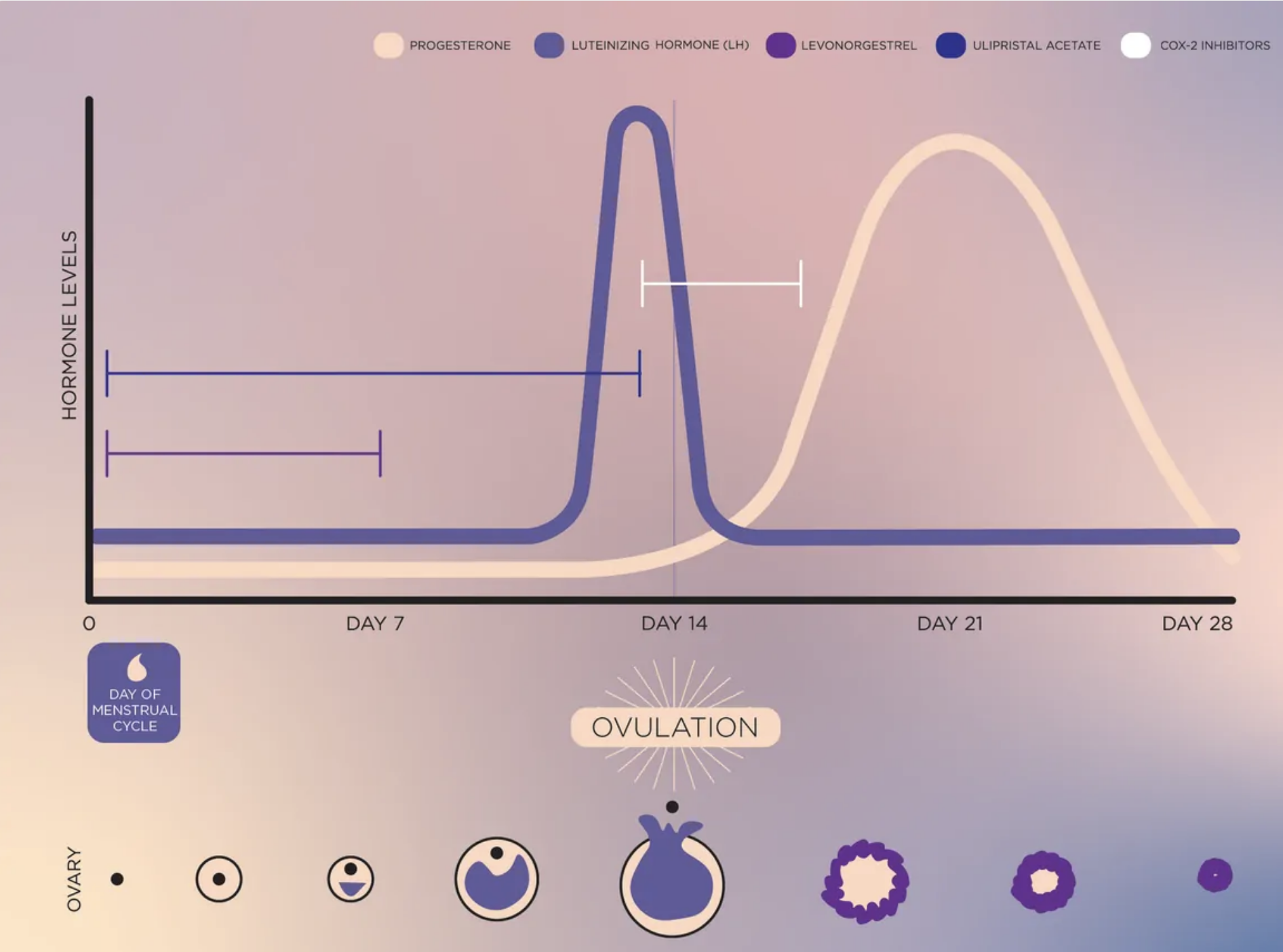

Fertility awareness methods (FAMs) are ways to track your menstrual cycle and fertile days to prevent pregnancy. Charting the basal body temperature and keeping track of a regular cycle (see chart below) allows one to determine the likelihood of being fertile. FAMs are also called “natural family planning” and “the rhythm method.” The days near ovulation are your fertile days — when you are most likely to get pregnant. So people use FAMs to prevent pregnancy by avoiding sex or using another birth control method (like condoms) on those fertile days. FAMs have a typical-use efficacy ranging from 77% to 98%. A review by (Duane et al. 2010) reported that with correct use the FAM method had a typical-use efficacy of 85%, noting that recognizing the beginning of the fertile window is more difficult than the end due to the variability of the follicular phase. The better you are about using FAMs the right way — tracking your fertility signs daily and avoiding sex or using birth control on fertile days — the more effective they’ll be. But like all methods besides abstinence, there’s a chance that you’ll still get pregnant, even if you always use them perfectly.

Barrier methods

Barrier methods rely on the ability to physically block sperm from reaching the ovulated egg, thereby preventing fertilization. These include condoms, diaphragms, cervical caps, and spermicides.

Condoms – 87% Typical-Use Efficacy. Small, thin pouches that cover the penis during sex and collect semen. Condoms must be put on correctly before sex. The added benefit is that some* condoms can offer protection against some sexually transmitted infections. “Pathogenic microorganisms including HIV cannot pass through high-quality male latex condoms” (Batar and Sivin, 2010) (* Lambskin condoms do NOT protect against STDs, because there are tiny holes in the lambskin that are small enough to block sperm but big enough to let bacteria and viruses through. So it’s best to use latex condoms to help prevent both STDs and pregnancy.)

Diaphragm – 83% Typical-Use Efficacy for women who have not yet given birth, 78% effective for women who have given birth. It is a shallow cup shaped like a little saucer that’s made of soft silicone. You bend it in half and insert it inside your vagina to cover your cervix. For a diaphragm to work best, it must be used with spermicide (a cream or gel that kills sperm). Less than 1% of women use diaphragms and most pharmacies no longer carry diaphragms (Schwartz 2019).

Cervical Cap – 86% Typical-Use Efficacy for women who have not yet given birth. For people who have given birth, the cervical cap is 71% effective. A cervical cap is a little cup made from soft silicone and shaped like a sailor’s hat. It must be fitted by a clinician. You put it deep inside your vagina to cover your cervix. It is an alternative to the sponge for those with “some vaginal abnormality” and “can be inserted up to one day before coitus…and left in place for more than 24 hours allowing for repeated intercourse” (Batar and Sivin 2010). For a cervical cap to work best, it must be used with spermicide. The FemCap, currently available, requires a prescription in the United States (Schwartz 2019).

The Sponge – 86% Typical-Use Efficacy. The birth control sponge (aka the contraceptive sponge or “the sponge” for short), is a small, round sponge made from soft, squishy plastic. You put it deep inside your vagina before sex. The sponge covers your cervix and contains spermicide to help prevent pregnancy. Each sponge has a fabric loop attached to it to make it easier to take out. It may remain in place for up to 30 hours but “removal should not be attempted until the passage of six hours following coitus” (Batar and Sivin, 2010). The Today sponge is available in the United States and contains N-9 1 spermicide that is released over the 24-hour period the sponge is left inserted in the vagina (Schwartz 2019).

Hormonal methods

Oral contraceptives work to block ovulation by acting on the HGP pathway. For a short review on this see the website.

Hormonal contraceptives involve the administration of synthetic versions of progesterone (progestin) with or without estrogen to inhibit ovulation and thicken cervical mucus to block fertilization. Progestin blocks GnRH from the hypothalamus (see image on right depicting HPG pathway), thus preventing ovulation. It also reduces cervical mucus permeability and endometrial receptivity.

Progestins are derived from 19 nor-testosterone and include norethindrone, norethindrone acetate, ethynodiol diacetate, norgestrel, levonorgestrel, norethynodrel, desogestrel, norgestimate, and gestodene (Horvath, Schreiber, and Sonalkar 2018). Estrogen also inhibits GnRh release and blocks FSH preventing the formation of the dominant follicle. Estrogen also reduces irregular bleeding and therefore it is often used in combination with progestin to produce a more consistent and regular period. Three different types of estrogens are used: ethinyl estradiol (EE), mestranol, and estradiol valerate (Horvath et al., 2018). Keep in mind that there are complications attributable to both progestin and estrogen (see the contraindications section below).

Implant (Nexplanon) – 99% Efficacy

The birth control implant is a tiny, thin rod about the size of a matchstick. The implant releases synthetic progestin into your body. A nurse or doctor inserts the implant into your arm and that’s it — you’re protected from pregnancy for up to 5 years. There have been reports of issues with the implant however, “events associated with the insertion, localization, and removal of the Nexplanon were rare” (Reed et al. 2019). It is a “get-it-and-forget-it” birth control making it super convenient. If you decide you want to get pregnant or you just don’t want to have your implant anymore, your doctor can take it out. You’re able to get pregnant quickly after the implant is removed. For more information on Nexplanon see Palomba et al. ( 2012).

Hormone Shot – 96% Efficacy

The Depo shot (AKA Depo-Provera) is an injection of progestin that you get once every 3 months. Most of the time, a doctor or a nurse must give you the shot. So you have to make an appointment at a health center, and then remember to go to the appointment. But you also may be able to get a supply of shots at the health center to bring home and give yourself. For more information on Depo-Provera see Westhoff (2003).

Hormone Ring – 93% Typical-Use Efficacy

A small, flexible ring inside your vagina, and prevents pregnancy 24/7 by releasing hormones into your body. There are two types, NuvaRing and Annovera which both disperse synthetic estrogen and progestin equally. The NuvaRing lasts for up to 5 weeks and you take your old NuvaRing out of your vagina and put in a new one about once a month, depending on the ring schedule you choose. One Annovera ring lasts for 1 year (13 cycles). You put the Annovera ring in your vagina for 21 days (3 weeks), then take it out for 7 days. For more information on the NuvaRing see (Roumen 2008).

Hormone Patch – 93% Typical-Use Efficacy

The transdermal patch is worn on certain parts of your body, and it releases a combination of progestin and estrogen through your skin that prevents pregnancy. To get the patch’s full birth control powers, you have to use it correctly. Making a mistake — like forgetting to refill your prescription or not putting on a new patch on time — is the main reason why people might get pregnant when they’re using the patch.

Hormone Pill – 93% Typical-Use Efficacy but it is important to note that certain drugs can interfere with the effectiveness of the pill because it is metabolized via the hepatic cytochrome P450 pathway (Teal and Edelman 2021). For example, antibiotic rifampin; certain antifungals that are taken orally for yeast infections; certain anti-HIV protease inhibitors; certain anti-seizure medications; & St. John’s Wort can decrease the effectiveness. There are some health risks associated with the pill. Women over 35 who smoke should not use the pill due to an increased risk of abnormal blood clot formation. There is also an elevated risk (20-30%) of developing breast cancer when using progesterone-only pills (Fitzpatrick et al. 2023). Birth control pills come in a pack, and you take 1 pill every day. The pill is safe, affordable, and effective if you always take your pill on time. “Originally, birth control pills were dosed with 21 days of active drug and a 7-day placebo week to trigger a monthly withdrawal bleed, meant to mimic the natural menstrual cycle” (Teal and Edelman, 2021). Problems associated with the placebo week led to the development of pills with shorter placebo periods (4 days) or none at all (continuous-dose pills).

Good news! You no longer need a prescription for birth control pills. The Opill is an over-the-counter pill now available. The FDA recently approved the first over-the-counter birth control pill norgestrel (Opill). Opill, also known as the “mini-pill,” contains a single hormone, progestin, and is taken daily. Research conducted by Anna Glasier et al. (2022; 2023) was used as part of the FDA approval process and highlights the mechanism of action of norgestrel and how missing a single dose of norgestrel does not hurt efficacy.

Q&A with Dr. Anna Glasier, OBE, Ph.D., the first Women’s Health Champion for Scotland.

College of Medicine and Veterinary Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK

What drew you to studying women’s reproductive health specifically contraception? Scotland has a long tradition of interest in Women’s Reproductive Health. When I started training in obstetrics and gynecology the MRC Unit of Reproductive Biology in Edinburgh had just moved into a new building physically attached to the maternity and gynecology hospital services, so it was hard to avoid developing a strong interest, including a research interest in RH. Moreover, there were individual clinicians and scientists (like David Baird and Roger Short) who were inspirational.

What have you enjoyed most about your career and what is it like to be recognized (receiving the OBE) for your work? I have been extremely lucky to have had such a great career. I enjoyed almost every aspect of my work including seeing patients. However, my career as a clinical researcher led to my being involved with a lot of international work which was very stimulating. I worked for many years with the World Health Organization in Geneva and with the Population Council in New York. For me, being recognized for my expertise by scientific organizations is important and fulfilling. Getting a paper published in a high-impact journal such as the Lancet or New England Journal of Medicine is always a great reward for research efforts. I am proud of the role I played in the UK and the US in getting emergency contraception and more recently progestogen-only pills available without needing to see a doctor. Finally, I was delighted to be asked to become the Women’s Health Champion for Scotland at a very late time in my career.

How do you see the career path for women in science has changed since you began and what do you hope for the future? I think it has become easier than it used to be for women to have a career in science. Part-time working or job-sharing has become much more acceptable allowing women to have a career and a family. Many organisations have a policy of encouraging women to participate at a senior level.

What advice do you have for future women scientists? I am most familiar with doing clinical research. My advice to junior clinicians is to accept every opportunity to participate in clinical research, recruit patients for colleagues who are doing studies, and take an active interest in their research and you might end up having a career as enjoyable as mine.

Contraindications of hormonal contraceptives

A contraindication is a specific factor that makes the birth control method potentially harmful for a particular individual and therefore they should not use the particular method. For a long time, physicians have been aware of contraindications associated with hormonal combination methods (estrogen + progesterone), as well as estrogen-only methods. There are minimal medical conditions that contraindicate progestogen-only contraceptives. Specifically, instances of problems associated with blood flow have been noted such as an increased risk of venous thromboembolism as well as increased cardiovascular disease, particularly for women who smoke and/or are obese (Serfaty 2019). A recent study by Roland et al., 2024 found that women who used the birth control shot Depo-Provera (medroxyprogesterone acetate) for an extended period are more than five times more likely to develop brain tumors.

List of contraindications for hormonal contraceptives (keep in mind this is not an exhaustive list)

- Blood clots, e.g. deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, or clotting disorders

- Stroke or heart attack

- Certain cancers, e.g. breast cancer or liver cancer

- Liver disease

- Migraines with aura (neurological symptoms)

- High blood pressure that is not well managed

- Diabetes with complications

- Abnormal uterine bleeding

- An increase in the risk of intracranial meningioma has been found in Depo-Provera users

It is important to note that for women with underlying health conditions who want to use a hormonal method (e.g. a woman with a history of breast cancer choosing combined hormonal contraceptives) their physicians/nurse practitioners will be able to advise them.

Are hormonal contraceptive methods available for men? The only currently available contraceptive option for men is condoms. Research is underway that includes a testosterone plus progestin topical gel which suppresses sperm count (Teal and Edelman, 2021).

Intrauterine devices

An intrauterine device (IUD) inserted into the uterus blocks fertilization and implantation. There are two types of IUDs, copper and hormonal (progestin-only). The copper IUD directly interferes with sperm and the hormonal IUD also interferes with sperm and ovulation. It’s long-term and reversible. An IUD has to be put in by a doctor, nurse, or other health care provider and the cost may be covered by insurance. Your IUD will protect you from pregnancy for 3 to 12 years, but your doctor or nurse can take it out any time before that if you like.

Permanent methods (Sterilization)

Permanently preventing pregnancy involves surgery performed by a physician or clinician. The cost of sterilization varies and depends on where you get it, what kind you get, and whether or not you have health insurance that will cover some or all of the cost. Over one-third of women choose sterilization as their contraceptive method, making it the most common method (Mosher and Jones 2010). There are two types of female sterilization: tubal ligation and bilateral salpingectomy.

- Tubal Ligation – Surgical procedure that permanently closes, cuts, or removes pieces of your fallopian tubes.

- Bilateral salpingectomy – Surgical procedure that removes your fallopian tubes entirely.

Emergency contraception

Unfortunately, there are a lot of misconceptions surrounding emergency contraception (EC). EC does not affect implantation or harm the embryo instead it prevents fertilization by blocking ovulation (Gemzell-Danielsson, Rabe, and Cheng 2013). As defined by the World Health Organization, EC methods are “methods of contraception that can be used to prevent pregnancy after sexual intercourse. These are recommended for use within 5 days but are more effective the sooner they are used after the act of intercourse.” The mode of action is to prevent or delay ovulation and modulate sperm activity without affecting an established pregnancy.

Plan B is a high dose of levonorgestrel (progestin) that has an 89% efficacy rate and is available over the counter for up to 72 hours after unprotected intercourse. It has a limited window of action. Studies show that levonorgestrel has a significant inhibitory effect on ovulation taken two days before the LH surge without affecting endometrial receptivity (Endler, Li, and Gemzell Danielsson 2022). Plan B is not recommended for women with a BMI greater than 30 (Cleland et al. 2020)

The drug ulipristal acetate (UPA) sold under the brand name Ella has a very high efficacy (99%) even when the probability of conception is at its highest because it behaves as an agonist when progesterone levels are low, but as progesterone increases, UPA acts antagonistically, inhibiting the LH surge, therefore, preventing ovulation (Rosato, Farris, and Bastianelli 2016). It is also indicated for use up to 120 hours after unprotected intercourse. Yet you must have a prescription to obtain UPA and it is not recommended for women with a BMI greater than 35.

The copper-bearing IUD sold under the name ParaGard can also act as an EC by causing a chemical change that prevents fertilization. It appears to be highly effective as long as it is inserted within the five-day window, studies have shown that over 99% of those who use a copper IUD as an emergency contraceptive method do not become pregnant (Goldstuck and Cheung 2019).

We must keep in mind that not all women can freely make decisions regarding their reproductive health. As noted in the 2022 UN Population Fund Annual Report nearly 25% of all women, where data are available, are unable to say no to sex. A recent study found a significant relationship between unmet contraception needs and when women’s healthcare choices were decided on by their male partners (Agyekum et al. 2022). There is also limited access to contraception in some regions of the world and even in the United States of America pharmacists have illegally refused to fulfill birth control prescriptions and are often encouraged to do so by religious doctrine as exemplified in the essay entitled “Pharmacist refusal to provide contraceptive services” by Baalmann (Baalmann 2022).

Think, Pair, Share

What are some of the reasons that prevent women from using contraception?

How is contraceptive access connected to gender equity and empowerment?

Under what circumstances might a woman choose one contraceptive method over another?

Compare the health risks of going through an unintended pregnancy to the health risks of using hormonal contraceptives.

Deeper Questions

Why might a woman falsely think that if they are using birth control they cannot say no to sex?

Why do you think that there are numerous contraceptive options for women but not for men and what might explain the fact that twice as many women seek sterilization as compared to men?

What forces exist today that resist efforts to make safe, reliable contraception available?

Key terms

Barrier method

Condom

Contraindication

Depo-Provera

Diaphragm

Emergency contraception

Fertility awareness method

Intrauterine device

Levonorgestrel

Nexplanon

NuvaRing

Typical-Use efficacy

Perfect Use efficacy

Spermicide

Sterilization

Transdermal patch

Ulipristal acetate

References

Agyekum, A. K., K. S. Adde, R. G. Aboagye, T. Salihu, A. Seidu, and B. O. Ahinkorah. 2022. “Unmet Need for Contraception and Its Associated Factors among Women in Papua New Guinea: Analysis from the Demographic and Health Survey.” Reproductive Health 19 (1): 113. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-022-01417-7.

Anderson, D. J., and D. S. Johnston. 2023. “A Brief History and Future Prospects of Contraception.” Science 380 (6641): 154–58. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adf9341.

Arteaga, S. and A. M. Gomez. 2016. “‘Is That A Method of Birth Control?’ A Qualitative Exploration of Young Women’s Use of Withdrawal.” The Journal of Sex Research 53 (4–5): 626–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2015.1079296.

Baalmann, A. 2022. “Pharmacist Refusal to Provide Contraceptive Services” 22 (1).

Batar, I., and I. Sivin. 2010. “State-of-the-Art of Non-Hormonal Methods of Contraception: I. Mechanical Barrier Contraception.” European Journal of Contraception and Reproductive Health Care 15 (2): 67–88. https://doi.org/10.3109/13625181003708683.

Bearak, J., A. Popinchalk, B. Ganatra, A. Moller, O. Tunçalp, C. Beavin, L. Kwak, and L. Alkema. 2022. “Unintended Pregnancy and Abortion by Income, Region, and the Legal Status of Abortion: Estimates from a Comprehensive Model for 1990–2019.” https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30315-6.

CDC. 2021. “Data and Statistics: Need for Contraceptive Services Among Women of Reproductive Age.” 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/contraception/data-and-statistics-contraceptive-services.html#:~:text=MMWR%20Morb%20Mortal%20Wkly%20Rep,70%3A910%E2%80%93915.)&text=76.2%25%20of%20women%20aged%2018,73.7%25%20(New%20York).

Cleland, K., B. Wagner, N. K. Smith, and J. Trussell. 2020. “‘My BMI Is Too High for Plan B.’ A Changing Population of Women Seeking Ulipristal Acetate Emergency Contraception Online.” Women & Health 60 (3): 241–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2019.1635560.

Duane, M., J. B. Stanford, C. A. Porucznik, and P. Vigil. 2010. “Fertility Awareness-Based Methods for Women’s Health and Family Planning.” Frontiers in Medicine, 858977.

Eig, J. 2014. The Birth of the Pill: How Four Crusaders Reinvented Sex and Launched a Revolution. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Endler, M., R. Li, and K. Gemzell Danielsson. 2022. “Effect of Levonorgestrel Emergency Contraception on Implantation and Fertility: A Review.” Contraception 109: 8–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2022.01.006.

Fitzpatrick, D., K. Pirie, G. Reeves, J. Green, and V. Beral. 2023. “Combined and Progestagen-Only Hormonal Contraceptives and Breast Cancer Risk: A UK Nested Case–Control Study and Meta-Analysis.” https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1004188.

Friedman, L., C. D. Furberg, and D. L. DeMets. 2010. Fundamentals of Clinical Trials. 4th ed. New York: Springer.

Gemzell-Danielsson, K., T. Rabe, and L. Cheng. 2013. “Emergency Contraception.” Gynecological Endocrinology 29 (sup1): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3109/09513590.2013.774591.

Goldstuck, N., and T. S. Cheung. 2019. “The Efficacy of Intrauterine Devices for Emergency Contraception and beyond: A Systematic Review Update.”

Horvath, S., C. A. Schreiber, and S. Sonalkar. 2018. “Contraception.” Endotex. 2018. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279148/.

Jones RK, Lindberg LD, Higgins JA. Pull and pray or extra protection? Contraceptive strategies involving withdrawal among US adult women. Contraception. 2014 Oct;90(4):416-21. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.04.016. Epub 2014 May 9. PMID: 24909635; PMCID: PMC4254803.

Khan, F., S. Mukhtar, I. K. Dickinson, and S.Sriprasad. 2013. “The Story of the Condom.” Indian Journal of Urology : IJU : Journal of the Urological Society of India 29 (1): 12–15. https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-1591.109976.

Mark, N. D. E., and L. L. Wu. 2022. “More Comprehensive Sex Education Reduced Teen Births: Quasi-Experimental Evidence.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 119 (8). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2113144119.

Marks, L. 2003. “A ‘Cage’of Ovulating Females”: The History of the Early Oral Contraceptive Pill Clinical Trials, 1950–1959.” In Molecularizing Biology and Medicine: New Practices and Alliances, 1920s to 1970s. Taylor & Francis.

———. 2010. Sexual Chemistry: A History of the Contraceptive Pill. Yale University Press.

Mosher, W. D., and J. Jones. 2010. “Use of Contraception in the United States: 1982-2008.” Vital Health Stat 23, no. 29 (August): 1–44.

Palomba, S., A. Falbo, A. Di Cello, C. Materazzo, and F. Zullo. 2012. “Nexplanon: The New Implant for Long-Term Contraception. A Comprehensive Descriptive Review.” Gynecological Endocrinology 28 (9): 710–21. https://doi.org/10.3109/09513590.2011.652247.

Pearson, R. M. 1986. “Vaginal Contraceptives Still Evolving.” Network (Research Triangle Park, N.C.) 7 (2): 6.

Pincus, G., J. Rock, C. Garcia, E. Rice-Wray, M. Paniagua, and I. Rodriguez. 1958. “Fertility Control with Oral Medication.” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 75 (6): 1333–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(58)90722-1.

Reed, S., T. D. Minh, J. A. Lange, C.l Koro, M. Fox, and K. Heinemann. 2019. “Real World Data on Nexplanon® Procedure-Related Events: Final Results from the Nexplanon Observational Risk Assessment Study (NORA).” Contraception 100 (1): 31–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2019.03.052.

Roland, N. A. Neumann, L. Hoisnard, L. Duranteau, S. Froelich, M. Zureik, and A. Weill. 2024. “Use of Progestogens and the Risk of Intracranial Meningioma: National Case-control Study.” British Medical Journal 284:e078078.

Rosato, E., M. Farris, and C. Bastianelli. 2016. “Mechanism of Action of Ulipristal Acetate for Emergency Contraception: A Systematic Review.” Frontiers in Pharmacology 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2015.00315.

Roumen, F. J. 2008. “Review of the Combined Contraceptive Vaginal Ring, NuvaRing®.” Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management 4 (2): 441–51. https://doi.org/10.2147/tcrm.s1964.

Schwartz, J. 2019. “Barrier Methods of Contraception.” In Speroff & Darney’s Clinical Guide to Contraception. LWW.

Serfaty, D. 2019. “Update on the Contraceptive Contraindications.” Journal of Gynecology Obstetrics and Human Reproduction 48 (5): 297–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogoh.2019.02.006.

Teal, S., and A. Edelman. 2021. “Contraception Selection, Effectiveness, and Adverse Effects: A Review.” JAMA 326 (24): 2507–18. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.21392.

The Boston Women’s Health Book Collective. 2011. Our Bodies Ourselves. Touchstone.

- 2022. “UN Population Fund Annual Report.” https://www.unfpa.org/annual-report#:~:text=A%20year%20in%20review,-Responding%20to%20the&text=2022%20was%20a%20%22year%20of,million%20people%20forcibly%20displaced%20worldwide.

Westhoff, C.. 2003. “Depot-Medroxyprogesterone Acetate Injection (Depo-Provera®): A Highly Effective Contraceptive Option with Proven Long-Term Safety.” Contraception 68 (2): 75–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-7824(03)00136-7.

Suggested Reading

“Taking Charge of Your Fertility” by Toni Weschler – This comprehensive guide provides in-depth information about fertility awareness-based methods of contraception and natural family planning. It includes charts, illustrations, and practical advice for tracking your menstrual cycle.

“The Pill: Are You Sure It’s for You?” by Jane Bennett and Alexandra Pope – This book explores the history and potential side effects of oral contraceptives (birth control pills) and provides information to help individuals make informed decisions about their use.

“Devices and Desires: A History of Contraceptives in America” by Andrea Tone – This book delves into what it was like to buy, produce, and use contraceptives during a century of profound social and technological change.

“The Reproductive Health of Adolescents” by Jennifer L. Gibson and Judith S. Seifert – Geared toward healthcare professionals, educators, and parents, this book covers a wide range of topics related to adolescent reproductive health, including contraception, sexual education, and healthcare access.