11 Female-Specific Cancer

STUDENT LEARNING OUTCOMES

At the end of this chapter you should be able to:

- Restate the characteristics of cancer cells and explain the process of transformation

- Recall the difference between DCIS and IBC and explain the two types of IBC

- Describe how the molecular expression profile of a tumor is an important diagnostic step

- Compare the different risk factors for reproductive cancers

- Describe the different treatment options for each type of female-specific cancer

- Discuss the disparities in cancer incidence rates among women of color

Jane Cooke Wright, M.D., a Pioneer of Chemotherapy

Research into chemotherapy led to advancements in treatment and better cancer prognoses. Dr. Jane Cooke Write was an important pioneer in the use of chemotherapy to treat cancer, noted by Crosby (2014) as “one of the first scientists to test anti-cancer drugs on humans rather than solely on mice, discovering the use of the popular antimetabolite drug methotrexate on solid tumours”. Wright et al. (1957) demonstrated the efficacy of this chemotherapy agent in human cancer tumors leading to a cure for choriocarcinoma (Li et al. 1958). In a tribute to Cooke by Edith Mitchell from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) in 2021 Wright is referred to as “The Mother of Chemotherapy.” Yet, a comprehensive paper on the history of chemotherapy by DeVita and Chu published in 2008 and cited over 2,222 times, fails to mention Cooke. From her NY Times Obituary (Weber, 2013) it is clear that the omission is problematic:

Jane Cooke Wright was the first Black woman to be named associate dean of a nationally recognized medical institution, the New York Medical College in 1967, and at the time, she was the highest-ranking African American woman at a U.S. medical school. In 1949, along with her father, Dr. Louis Wright who had established the Cancer Research Center at Harlem Hospital, she started testing chemical anti-cancer agents (chemotherapy) on human leukemias and other cancers. This research led to her seminal work in 1951 which established the efficacy of methotrexate in treating breast cancer. This research laid the foundations for treating tumors with chemotherapy. She was also instrumental in using a personalized approach to cancer, recognizing that individual tumors required separate analyses and treatments. Jane Cooke Wright became director of the Cancer Research Center following her father’s death in 1952. In 1955, she became an associate professor of surgical research at New York University Medical Center and was appointed to the President‘s Commission on Heart Disease, Cancer, and Stroke by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964. Wright was also a founding member of the American Society of Clinical Oncology and served on the board of directors of the American Cancer Society, New York. She published more than 100 papers throughout her career and led delegations of cancer researchers to Africa, Asia, and Eastern Europe.

Wright played a vital role in the advancement of the treatment and care and she should be recognized for her contributions. When chemotherapies were first discovered there was hope of finding a “magic bullet” to cure cancer. As Mukherjee comments in his book The Emperor of all Maladies (2010) “How many of us have asked the question, ‘If this great country of ours can put a man on the moon why can’t we find a cure for cancer?” A multitude of researchers have been, and are working to find a cure but “what they’re learning is more of what they already learned — which is that cancers are extremely complex” (Hayden 2008). In this chapter, we will discuss the cancers that are more prevalent in females and are associated with female reproductive organs.

Cancer sucks, a brief overview of cancer

Nearly one million women in the United States received a cancer diagnosis in 2023 and over 287,700 died of the disease. Most importantly, the incidence trends are less favorable for women when compared to men (Siegel et al., 2023). Cancer is a complex genetic disease.

Six key characteristics of cancer cells have been identified (reviewed by Hanahan and Weinberg 2011)

- dividing without limits (cell proliferation)

- resisting cell death (anti-apoptosis)

- inducing the formation of new blood vessels (angiogenesis)

- resisting anti-growth signals

- inducing growth signals

- activating the movement of cells from the tumor that travel through the bloodstream or lymphatic system, and establishing secondary tumors in distant parts of the body (metastasis)

Benign tumors remain localized and confined in their original growth site whereas cancerous (malignant) tumors can spread into other tissues (metastasize). Cells become cancerous through a multistep process usually involving multiple mutations accumulating over time that lead to the transformation of the cell. These mutations turn proto-oncogenes into oncogenes and deactivate tumor suppressor genes and DNA repair genes. Proto-oncogenes are involved in the regulation of cell division and cell-cell contact. Tumor suppressor genes are involved in controlling programmed cell death and DNA repair genes are critical in maintaining the integrity of the genome.

Cancers often develop in progressive steps going from slightly abnormal to tumorigenic to malignant to metastatic. When cells begin to divide abnormally they are known as dysplasia. Additional mutations occur leading to these cells becoming increasingly abnormal and referred to as carcinomas in situ. In time the tumor exhibits “a high degree of genomic complexity…which…drives the evolution of tumor response or resistance to therapy” (Hurvitz et al., 2021). Once a tumor becomes malignant it can become metastatic.

Specific types of cancer are designated by their primary site of origin, e.g. breast cancer starts in the breast tissue cells. Breast cancer is the most common cancer diagnosed in women in the United States whereas lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths (Sung et al. 2021). Early diagnosis of cancer and access to effective treatments are essential for a good prognosis.

Breast cancer (BC)

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women, impacting one out of every eight women (Siegel et al. 2023). Men also can develop breast cancer, however, this is very rare (the incidence of BC in men is 1 of 883). Thankfully, advancements in screening, diagnosis, and treatment have increased breast cancer survival rates. However, breast cancer remains a significant health issue despite advancements in screening and treatment for several reasons such as the presence of aggressive subtypes, underlying genetic factors, tumor resistance to treatment, and health disparities.

Different subtypes of BC

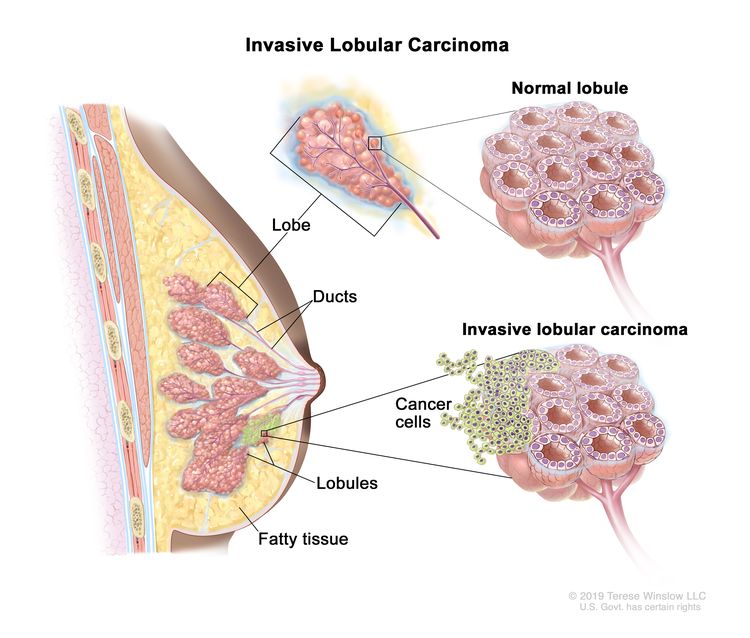

Like all cancers, breast cancer is a diverse and complex disease. Within the ductal-lobular unit of the breast, abnormal cells may arise resulting in lesions that can develop into atypical ductal hyperplasia and then into premalignant ductile carcinoma in situ (DCIS). DCIS, illustrated on the right, is a non-invasive type of pre-cancer with the “highly variable potential of becoming invasive however”…“studies on DCIS from non-treated patients show that many lesions, if left alone, will never progress to invasive disease” (Bergholtz et al. 2020).

Invasive breast cancer (IBC) means that the cancerous cells have spread to surrounding tissue and left untreated will metastasize (image above). Invasive breast cancer may or may not arise from DCIS and symptoms may include a “swelling or lump in the breast, swelling in the armpit (lymph nodes), nipple discharge (clear or bloody), pain in the nipple, inverted (retracted) nipple, scaly or pitted skin on the nipple, persistent tenderness of the breast, and unusual breast pain or discomfort” (Sharma et al. 2010). IBC is a very diverse disease, however, two general subtypes are recognized Łukasiewicz et al. (2021):

- invasive breast cancer of no special type (NST), formerly known as invasive ductal carcinoma (this is the most frequent subgroup up to 80%)

- invasive breast cancer of special type

Within these two groups, breast cancer is further classified by molecular expression of different receptors, growth factors, and proliferation markers associated with the tumor.

Łukasiewicz et al. (2021) report that 70% of all global breast cancer cases are ER+, whereas 10-15% are HER2-. Identification of these molecular subtypes improves outcome predictions. For example, those described as having a Luminol A category tumor (ER+ and PR+, but HER2-) have the best prognosis, followed by the Luminol B category tumor (ER+ and PR-, and HER2- with Ki67), and then Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC) also known as basal-like BC is ER-, PR-, and HER2- with the worst prognosis. TNBC constitutes about 20% of all breast cancers and is more common among women younger than 40 years of age and African-American women. There is also an association between socioeconomic status, level of education, and incidence of HER2- and TNBC subtypes relative to the less aggressive Luminal A subtype (Aoki et al. 2021).

Another key reason to identify tumors based on molecular subtype is that several treatments have been developed to directly target different molecular subtypes and patients can be spared chemotherapy in these cases (Lau, Tan, and Shi 2022).

Risk factors associated with BC

- Being female

Compared to men, women are much more vulnerable to the development of breast cancer because of hormonal differences. A positive relationship between the activity of estrogens and an increased risk of breast cancer has been documented (Aubé, Larochelle, and Ayotte 2008). Estrogen exerts stimulatory effects while androgens exert inhibitory effects regulating cell proliferation in breast cells and when this balance is disrupted progression of cancer may occur (Labrie 2006). In menopausal women taking hormone replacement therapy (HRT) with estrogen and progesterone research indicates there is an increased risk of luminal A breast cancer, however, the risk significantly decreases after two years of stopping HRT (Sun et al. 2017).

- Age

Like most cancers, the older one gets the greater the risk of developing breast cancer. Most breast cancers are diagnosed after age 50. However, where a woman lives can make a difference, women living in African and Asian countries are being diagnosed at younger ages (Kabat et al. 2017).

- Parity

Parity is carrying a pregnancy to a viable age. Fortner et al. (2019) found that greater parity is associated with a substantially lower risk of ER+ cancer but not ER- cancer and that breastfeeding duration is correlated with a lower risk of ER- cancer. Compared to nulliparous women (having never carried a pregnancy to birth), higher parity was inversely associated with luminal B breast cancer.

- Lifestyle

Alcohol consumption and an overconsumption of dietary fat intake can increase the risk of breast cancer. Alcohol consumption can elevate the level of estrogen-related hormones in the blood and trigger the estrogen receptor pathways. Research combining 20 cohort studies found a positive association between alcohol consumption and breast cancer subtypes ER+ PR+, ER+ PR-, and ER-PR- (Jung et al. 2016). Body fat may contribute to the development of breast cancer but the mechanism is unclear and an increased risk of breast cancer is correlated to high body mass index for some populations but not all (Pettersson and Tamimi 2012). Increased body size in pre-menopausal women was linked to an increased risk of developing TNBC (Turkoz et al. 2013).

- Genetics

Exposure to carcinogens (e.g. smoking) and spontaneous mutations (e.g. DNA replication error) in oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes lead to cancer. Individuals can also inherit mutations that elevate the risk of developing BC however, “8/9 women who develop breast cancer do not have an affected mother, sister, or daughter” (Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer 2001). Numerous genes have been identified as playing a role in breast cancer development.

The most well-characterized genes associated with BC (reviewed by Sun et al., 2017):

Breast cancer associated gene 1 and 2 (BRCA1 and BRCA2) are tumor suppressor genes. The majority (approximately 80%) of breast cancers arising from BRCA1 germline mutation are TNBC.

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), also known as c-erbB-2, is an important proto-oncogene in breast cancer. HER2 protein is an epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) form heterodimers with other ligand-bound EGFR family members such as Her3 and Her4, thus activating downstream signaling pathways

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), also known as c-erbB-1 or Her1 in humans, is a proto-oncogene that encodes the EGFR protein. This is a cell surface glycoprotein activated by ligands that trigger downstream signaling pathways. Overexpression of EGFR is found in more than 30% of cases of inflammatory breast cancer (IBC), a very aggressive subtype of breast cancer.

c-Myc is a proto-oncogene that encodes a transcription factor involved in the initiation and progression of breast cancer.

Detection and treatment of BC

Being familiar with the appearance and feel of one’s breasts can help one notice changes that may be of concern. However, mammograms (an X-ray of the breast) are the best way to screen for BC. Drawbacks of mammograms include incidences of false positives and overtreatment as well as false negatives. A breast MRI is used along with mammograms to screen women who are at high risk for getting breast cancer. The United States Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) currently recommends that women who are ages 50 to 74 get a mammogram every two years (USPSTF, 2016) however the USFSTF is now in the process of updating these guidelines.

Molecular screening for biomarkers helps to determine which therapies are most effective. For example, ER+ status indicates the use of endocrine therapy such as Tamoxifen or an aromatase inhibitor. Tamoxifen is a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) that blocks the effects of estrogen on ER+ breast cancer cells. Aromatase inhibitors block the conversion of androgen into estrogen. Anti-HER2 therapy such as Herceptin targets HER2- positive breast carcinomas.

Surgery for BC

Surgery involves the removal of the tumor and a small amount of surrounding tissue (lumpectomy / breast-conserving surgery) or the removal of the breast (mastectomy). More women are choosing a mastectomy over breast-conserving surgery. A review and meta-analysis of over 1.3 million breast cancer patients found that those receiving breast-conserving surgery experienced significantly better overall survival and breast cancer-specific survival than patients treated with mastectomy (Christiansen et al. 2022).

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy (RT) involves focusing radiation on the area affected by the cancer or on the whole breast.

Chemotherapy

Multiple drugs that inhibit cell division are usually prescribed in combination to minimize tumor evolution. These have side effects depending on the type, dose, and length of time given but the side effects generally abate after treatment is finished. For younger women, premature menopause may occur leading to infertility.

Treatment options depend on the progression of the disease and the molecular subtype. For DCIS the goal is to prevent these potential cells from transforming into invasive carcinoma. Studies indicate that lumpectomy combined with RT reduces DCIS recurrence (Kalwaniya et al. 2023). For IBC that has not yet spread chemotherapy is used to reduce tumor size and then surgery is performed. Whole-breast RT is generally used after breast-conserving surgery. For tumors with the triple negative molecular profile (TNBC), chemotherapy is the main treatment. Anti-HER2 therapy is paired with chemotherapy to treat HER-2+ cancers. For metastatic breast cancer, therapeutic goals are prolonging life and symptom palliation. Currently, metastatic breast cancer remains incurable in virtually all affected patients (Riggio, Varley, and Welm 2021).

Q&A with Dr. Mary-Helen Barcellos-Hoff, PhD.,

Professor and Vice Chair, Research, Wun-Kon Fu Endowed Chair in Radiation Oncology,

University of California San Francisco

What drew you to researching radiation therapy, and specifically its effect on transforming growth factor beta for cancer treatment? My graduate degree is in Experimental Pathology, which was focused on using preclinical models to understand the development of disease. My graduate research concerned the response of cancer cells to radiation and chemotherapy standard of care. using a 3-dimensional model called multicellular tumor spheroids, which stimulated my interest in cell-cell interactions and morphogenesis. To learn more about the cell biology of normal tissues, I conducted postdoctoral research investigating the regulation of milk protein production in mouse mammary epithelial cultured in 3D on an extracellular matrix (ECM). When I began my own lab, I decided to study whether radiation affected the ECM, and if that contributed to the mechanisms by which radiation increases cancer. I found that the mammary gland ECM is remodeled upon radiation exposure is reminiscent of wound healing, which I knew from my graduate program in experimental pathology is regulated by TGFbeta. Hence, I tested whether TGFbeta is a mediator of the ECM remodeling and discovered that radiation actually induces TGFbeta activity. I have since studied what TGFbeta does in irradiated tissues to promote cancer and what role it plays in the response to radiotherapy.

What do you like most about your career? I like that I choose the problems to work on and that I can follow the science where it leads me using the unique insights gained from my own experiments and my particular knowledge of the literature. I also enjoy the element of serendipity in biological research—it is so vast that one’s knowledge is not just a sliver, but a self-curated sliver based on exposure and interests that generates new ideas. I like the independence, even though it comes at a high cost of insecurity because one must obtain funding and publish by subjecting to the critiques of others.

What advice do you have for future women scientists? Academic scientists must be self-motivated by curiosity but stubborn enough to prevail even when others critique their ideas. Like everyone else, scientists resist change in major paradigms, and the bar of proof is high to shift ideas. Cultural framing of how women should contribute to society is a barrier to promoting new ideas. Women scientists need to be cognizant of their own tendencies to step back and avoid conflict to reframe scientific debate in a gender-neutral fashion.

Cervical cancer

The WHO (2023) notes that globally, cervical cancer is the fourth most frequent cancer in women and it disproportionately affects those in low- and middle-income countries. The rates of cervical cancer have dropped dramatically in high-income countries thanks to regular screening via a Pap test (a medical screening test used to detect abnormal cervical cells in the cervix, which is the lower part of the uterus that opens into the vagina) and the administration of the HPV vaccine. As noted in the section on HPV, cervical cancer is caused by several types of HPV. Over time cervical cells become transformed and symptoms might include post-coital or abnormal vaginal bleeding and or pelvic pain.

Snijders et al. (2006) describe the molecular mechanism of HPV-mediated carcinogenesis. The HPV virus has two genes, E6 and E7 that encode for early proteins which inhibit tumor suppressors p53 and pRB. E6 also activates telomerase activity increasing cell proliferation. It also down-regulates the host immune response. E7 also increases genomic instability and promotes the accumulation of chromosomal abnormalities. This contributes to the transformation of the cell. E6 and E7 activation must also be combined by the accumulation of additional mutations before the cancer becomes invasive.

The progression of the disease involves interactions with HPV and cofactors. These cofactors include long-term smoking, high parity (five or more full-term pregnancies), long-term use of oral contraceptives, and HIV infection (de Sanjosé, Brotons, and Pavón 2018).

HPV prevention

Primary prevention of HPV

The introduction of HPV vaccines is instrumental in the prevention of cervical cancer and is “considered one of the most significant events in medicine and global healthcare” (Akhatova et al. 2022). The vaccines are highly effective in preventing HPV infection and diseases related to HPV infection when given to prepubertal girls and boys (Kechagias et al. 2022).

Secondary prevention

The Pap test is the original cervical screening cytological test to detect abnormal cells. However HPV-based screening using PCR is more efficacious at detecting cervical pre-cancers compared with cytology (Cohen et al. 2019).

Diagnosis and treatment of cervical cancer

Cohen et al., (2019) report that cervical examination using a colposcope (lighted magnifying instrument) allows for the viewing of abnormal lesions. A cone biopsy done under general anesthetic allows for histopathological assessment of the cervical tissue.

Surgery is the first line of treatment and the extent depends upon the progression of the disease. There are different types of surgery:

- radical hysterectomy (resection of the uterus, cervix, parametria, and cuff of the upper vagina)

- modified radical hysterectomy (less parametrium resection and a smaller vaginal cuff)

- bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy (dissection of pelvic lymph nodes)

- radical trachelectomy (resection of the entire cervix and upper vagina and parametrium) available for younger women wishing to preserve fertility

Locally advanced cervical cancer treatment often involves chemotherapy alone or combined with radiation therapy. Chemotherapy may also be used to treat metastatic cervical cancer.

Ovarian cancer

A complex disease, ovarian cancer causes more deaths than any other cancer of the female reproductive system (CDC, 2023). Death rates are so high because effective screening strategies for the early detection of ovarian cancer do not exist and diagnosis does not occur until later stages. However, the rates of ovarian cancer diagnosis are declining likely due to the increased use of oral contraceptives that contain hormones that suppress the menstrual cycle and prevent ovulation. By reducing the number of ovulatory cycles a woman goes through during her reproductive years, oral contraceptives may lower the risk of developing certain types of ovarian cancer, particularly those that originate in the ovarian surface epithelium (Fathalla 2013).

There are two broad categories of ovarian cancer, (1) epithelial and (2) non-epithelial, each further categorized by histology (what the tissue looks like). The vast majority of ovarian cancers are in the epithelial category, non-epithelial ovarian cancers account for ∼10% of ovarian cancers. Within the epithelial group, low-grade serous carcinomas (LGSCs) have a better prognosis, whereas high-grade serous carcinomas (HGSCs) account for 80% of all types of epithelial cancer (Stewart, Ralyea, and Lockwood 2019).

Risk factors for ovarian cancer

- Age

Most women with ovarian cancer are diagnosed in later life, with a median age of diagnosis of 63 years (Stewart, Ralyea, and Lockwood 2019).

- Genetics

Mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2 tumor suppressor genes are associated with ovarian cancer. Either mutation is found in up to 17% of patients (Matulonis et al. 2016). Inheritance of a germline mutation in genes involved with DNA repair mechanisms associated with Lynch syndrome has been observed in ovarian cancers (Stewart, Ralyea, and Lockwood 2019).

- Endometriosis

Endometriosis has been associated with endometrioid and clear-cell ovarian cancer, as well as low-grade cancers but the risk differs depending on the subgroup type of endometriosis (Heidemann et al. 2014).

- HRT

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) has been shown to increase the risk of developing ovarian cancer in postmenopausal women. However, the use of oral contraceptives in younger women has been shown to reduce the risk of developing ovarian cancer.

- Nulliparity

Women who have given birth have a reduced risk of all subtypes of ovarian cancer.

Tubal ligation and hysterectomy are associated with a reduction in the risk of developing ovarian cancer as well as the removal of one or more of the ovaries and fallopian tubes (unilateral or bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (removal of the ovaries and the fallopian tubes) Matulonis et al., 2016).

Diagnosis and treatment of ovarian cancer

Most women are asymptomatic however some may experience abdominal bloating, abdominal and/or pelvic pain, fatigue, and shortness of breath (Matulonis et al., 2016). Gastrointestinal problems such as diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and gastrointestinal reflux may occur. Detection involves transvaginal ultrasonography combined with a CA125 blood test. CA-125 stands for “cancer antigen 125”, a glycoprotein that is a biomarker (an indicator of a condition, or response to treatment) for ovarian cancer. However (Charkhchi et al. 2020) report that “early diagnosis of ovarian cancer at stages I and II through screening with CA125 has shown little promise…but hopefully in the future combining this with other biomarkers can increase the sensitivity.”

The first line of treatment includes cytoreduction (to shrink tumors) then chemotherapy followed by interval surgical cytoreduction and additional chemotherapy after surgery. Better outcomes are noted when surgery is performed by a gynecological oncologist rather than a general surgeon (Matulonis et al., 2016).

Uterine cancer

Uterine cancer is the most common gynecologic cancer and the incidence is on the rise (Lu and Broaddus 2020). There are two types of uterine cancer, endometrial cancer and uterine sarcoma. Endometrial cancer is much more common than uterine sarcoma which is found in 3-7% of uterine cancer patients (Mbatani, Olawaiye, and Prat 2018). Morice et al. (2016) provide a review of endometrial cancer noting that there are two subtypes of endometrial cancer: endometrioid and non-endometrioid. Type I, endometrioid cancer, accounts for 80% of endometrial cancers, and patients with this subtype have a good prognosis. Type I tumors are low-grade (slower-growing), estrogen-positive, diploid, and often involve the progression of precancerous cells (complex atypical hyperplasia, CAH). Whereas type II non-endometrioid tumors are high-grade (faster-growing), aneuploid, and hormone-independent, lacking precursor lesions, with a poor prognosis.

Risk factors for uterine cancer

- Obesity

Compared with other types of cancer in women, obesity is significantly more associated with endometrial cancer with over half of all endometrial cancers attributed to being overweight. This may be because after menopause adipose tissue, commonly known as fat, becomes the main site of estrogen synthesis which “acts not only as a mitogen, but also as a mutagen” (Onstad, Schmandt, and Lu 2016). Obesity is also associated with polycystic ovary syndrome, another risk factor for endometrial cancer (Barber and Franks 2021).

- Estrogen-only HRT

Unopposed estrogen increases the risk of endometrial cancer. Combined with progesterone, HRT does not pose a risk (Sjögren, Mørch, and Løkkegaard 2016).

- Tamoxifen

Tamoxifen, the breast cancer treatment that blocks estrogen receptors, actually has proestrogenic effects in the uterus, doubling the risk of both endometrioid and nonendometrioid types of endometrial cancer. When taken for more than five years the risk quadruples (O. Lavie et al. 2008).

Diagnosis and treatment of uterine cancer

The most common symptom is abnormal uterine bleeding which includes bleeding between periods or after sex or any unexpected bleeding after menopause (Henley et al. 2018). Although uterine cancer is more common in White women, racial disparity exists in the diagnosis of uterine cancer among Black patients with Black patients not receiving guideline-recommended diagnostic procedures or experiencing delays in diagnosis compared to White patients (Xu et al. 2023). Furthermore, Henley et al. (2018) examined incidence and mortality data from 1999-2016 and they found that Black women were twice as likely to die from uterine cancer as women in other racial groups.

An endometrial biopsy is used to confirm diagnosis however if there is uncertainty, cervical dilation, and curettage is recommended (Morice et al. 2016). Initial management of endometrial cancer is surgery involving the removal of the uterus, cervix, fallopian tubes, and ovaries along with lymph-node evaluation. For younger women who wish to remain fertile, those with CAH and low-grade tumors use of progestin-containing IUDs has shown success but recurrence rates remain high (Andress et al. 2021). Lu and Broaddus, (2020) report chemoradiation therapy followed by four cycles of carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy is the standard treatment for invasive cancer. However, similar to breast cancer, assessment of estrogen receptor (ER) progesterone receptor (PR), and epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER-2) status is now also conducted. Recent use of a combination of antihormonal and biologic agents has shown promise for second- or third-line treatment for endometrioid endometrial cancers.

The prevalence of cancer makes it a significant life-threatening disease for all. In 2022 the estimated number of new female-specific cancer cases was 402,980 and deaths were 75,080 (Siegel et al., 2022). The types and causes of cancer are very complex and as the population continues to age the burden of cancer will increase however advancements in screening and treatments make a real difference in the fight against cancer. The 20-year trend in breast cancer and ovarian cancer death rates in women is on a gradual decline, and the sharp decline in cervical cancer rates thanks to the HPV vaccine is notable. Since the 2016 launch of the Cancer Moonshot, a national effort prioritizing cancer research, over 250 research projects have been funded to improve treatments, map tumors, and expand prevention and detection (Sharpless and Singer 2021). However, disparities in the United States in prevention programs, screening, diagnosis, and treatment must also be addressed.

Think, Pair, Share

Early diagnosis of cancer is key to positive outcomes. What are some ways to improve getting people to take advantage of regular screenings early on?

How does lifestyle increase the risk of developing cancer?

What factors may be contributing to higher rates of breast and uterine cancer incidences in women of color?

How much does education level contribute to outcomes for women diagnosed with cancer?

Deeper Questions

What societal factors play into the decision a woman makes on whether or not she gets a mastectomy with reconstruction or breast-conserving surgery?

What factors can influence women of different ages to engage in preventative action to reduce their risk of cancer?

With the average price of cancer drugs doubling in the last decade, the unsustainability of drug prices is especially concerning in oncology. What can be done to make cancer treatments more affordable in the United States?

Key Terms

Benign

BRCA1 and BRCA2

Carcinogen

Carcinomas in situ

DCIS

Dysplasia

EGFR

ER+/ER-

IBC

HER2+

HGSC

HRT

LGSC

Malignancy

Metastasis

Nulliparity

Parity

PR+/PR-

Protooncogene

SERM

Tamoxifen

TNBC

Tumor suppressor gene

References

Akhatova, A., A. Azizan, K. Atageldiyeva, A. Ashimkhanova, A. Marat, Y. Iztleuov, A. Suleimenova, S. Shamkeeva, and G. Aimagambetova. 2022. “Prophylactic Human Papillomavirus Vaccination: From the Origin to the Current State.” Vaccines 10 (11). https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10111912.

Andress, J., J. Pasternak, C. Walter, S. Kommoss, B. Krämer, A. Hartkopf, S. Y. Brucker, B. Schönfisch, and S. Steinmacher. 2021. “Fertility Preserving Management of Early Endometrial Cancer in a Patient Cohort at the Department of Women’s Health at the University of Tuebingen.” Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics 304 (1): 215–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-020-05905-8.

Aoki, R.L.F., Uong, S.P., Gomez, S.L., Alexeeff, S.E., Caan, B.J., Kushi, L.H., Torres, J.M., Guan, A., Canchola, A.J., Morey, B.N. and Lin, K., 2021. Individual‐and neighborhood‐level socioeconomic status and risk of aggressive breast cancer subtypes in a pooled cohort of women from Kaiser Permanente northern California. Cancer 127(24): 4602-4612.

Aubé, M., C. Larochelle, and P. Ayotte. 2008. “1,1-Dichloro-2,2-Bis(p-Chlorophenyl)Ethylene (p,p’-DDE) Disrupts the Estrogen-Androgen Balance Regulating the Growth of Hormone-Dependent Breast Cancer Cells.” Breast Cancer Research 10 (1): R16. https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr1862.

Barber, T. M., and S. Franks. 2021. “Obesity and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome.” Clinical Endocrinology 95 (4): 531–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/cen.14421.

Bergholtz, H., T. G. Lien, D. M. Swanson, A. Frigessi, T. F. Bathen, E. Borgen, A. Lise Børresen-Dale, et al. 2020. “Contrasting DCIS and Invasive Breast Cancer by Subtype Suggests Basal-like DCIS as Distinct Lesions.” Npj Breast Cancer 6 (1): 26. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41523-020-0167-x.

Charkhchi, P., C. Cybulski, J. Gronwald, F. Oliver Wong, S. A. Narod, and M. Akbari. 2020. “CA125 and Ovarian Cancer: A Comprehensive Review.” Cancers 12 (12): 3730. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12123730.

Christiansen, P., M. Mele, A. Bodilsen, N. Rocco, and R. Zachariae. 2022. “Breast-Conserving Surgery or Mastectomy?: Impact on Survival.” Annals of Surgery Open : Perspectives of Surgical History, Education, and Clinical Approaches 3 (4): e205. https://doi.org/10.1097/AS9.0000000000000205.

Cohen, P. A., A. Jhingran, A. Oaknin, and L. Denny. 2019. “Cervical Cancer.” The Lancet 393 (10167): 169–82.

Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. 2001. “Familial Breast Cancer: Collaborative Reanalysis of Individual Data from 52 Epidemiological Studies Including 58 209 Women with Breast Cancer and 101 986 Women without the Disease.” The Lancet 358 (9291): 1389–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06524-2.

Crosby H.L. 2016. Jane Cooke Wright (1919–2013): Pioneering oncologist, woman and humanitarian. Journal of Medical Biography. 24(1):38-41.

DeVita Jr, V.T. and Chu, E., 2008. A history of cancer chemotherapy. Cancer research 68 (21):8643-8653.

Fathalla, M. F. 2013. “Incessant Ovulation and Ovarian Cancer – a Hypothesis Re-Visited.” Facts, Views & Vision in ObGyn 5 (4): 292–97.

Fortner, R. T., J. Sisti, B. Chai, L. C. Collins, B. Rosner, S. E. Hankinson, R. M. Tamimi, and A. H. Eliassen. 2019. “Parity, Breastfeeding, and Breast Cancer Risk by Hormone Receptor Status and Molecular Phenotype: Results from the Nurses’ Health Studies.” Breast Cancer Research 21 (1): 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-019-1119-y.

Hanahan, D., and R. A. Weinberg. 2011. “Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation.” Cell 144 (5): 646–74.

Hayden, E. C., 2008. Cancer complexity slows quest for cure. Nature 455 (7210):148.

Heidemann, L. N., D. Hartwell, C. H. Heidemann, and K. M. Jochumsen. 2014. “The Relation between Endometriosis and Ovarian Cancer – a Review.” Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 93 (1): 20–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.12255.

Henley, S. J., J. W. Miller, N. F. Dowling, V. B. Benard, and L. C. Richardson. 2018. “Uterine Cancer Incidence and Mortality – United States, 1999-2016.” MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 67 (48): 1333–38. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6748a1.

Jung, S., M. Wang, K. Anderson, L. Baglietto, L. Bergkvist, L. Bernstein, P. A. van den Brandt, et al. 2016. “Alcohol Consumption and Breast Cancer Risk by Estrogen Receptor Status: In a Pooled Analysis of 20 Studies.” International Journal of Epidemiology 45 (3): 916–28. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyv156.

Kabat, G. C., M. Ginsberg, J. A. Sparano, and T. E. Rohan. 2017. “Risk of Recurrence and Mortality in a Multi-Ethnic Breast Cancer Population.” Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 4 (6): 1181–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-016-0324-y.

Kalwaniya, D. S., M. Gairola, S. Gupta, and G. Pawan. 2023. “Ductal Carcinoma in Situ: A Detailed Review of Current Practices.” Cureus 15 (4): e37932. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.37932.

Kechagias, K. S., I. Kalliala, S. J. Bowden, A. Athanasiou, M. Paraskevaidi, E. Paraskevaidis, J. Dillner, et al. 2022. “Role of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccination on HPV Infection and Recurrence of HPV Related Disease after Local Surgical Treatment: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” BMJ 378 (August): e070135. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2022-070135.

Labrie, F. 2006. “Dehydroepiandrosterone, Androgens and the Mammary Gland.” Gynecological Endocrinology : The Official Journal of the International Society of Gynecological Endocrinology 22 (3): 118–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/09513590600624440.

Lau, K. H., A. M. Tan, and Y. Shi. 2022. “New and Emerging Targeted Therapies for Advanced Breast Cancer.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23 (4). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23042288.

Li, M.C., Hertz, R. and Bergenstal, D.M., 1958. Therapy of choriocarcinoma and related trophoblastic tumors with folic acid and purine antagonists. New England Journal of Medicine, 259 ( 2):66-74.

Lu, K. H., and R. R. Broaddus. 2020. “Endometrial Cancer.” New England Journal of Medicine 383 (21): 2053–64. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1514010.

Łukasiewicz, S., M. Czeczelewski, A. Forma, J. Baj, R. Sitarz, and A. Stainslawek. 2021. “Breast Cancer—Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Classification, Prognostic Markers, and Current Treatment Strategies—An Updated Review.” Cancers 13 (17): 4287. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13174287.

Matulonis, U. A., A. K. Sood, L. Fallowfield, B. E. Howitt, J. Sehouli, and B. Y. Karlan. 2016. “Ovarian Cancer.” Nature Reviews Disease Primers 2 (1): 16061. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2016.61.

Mbatani, N., A. B. Olawaiye, and J. Prat. 2018. “Uterine Sarcomas.” International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 143 (S2): 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.12613.

Morice, P., A. Leary, C. Creutzberg, N. Abu-Rustum, and E. Darai. 2016. “Endometrial Cancer.” Lancet (London, England) 387 (10023): 1094–1108. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00130-0.

Lavie, O. Barnett-Griness, S. A. Narod, and G. Rennert. 2008. “The Risk of Developing Uterine Sarcoma after Tamoxifen Use.” International Journal of Gynecologic Cancer 18 (2): 352. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.01025.x.

Onstad, M. A., R. E. Schmandt, and K. H. Lu. 2016. “Addressing the Role of Obesity in Endometrial Cancer Risk, Prevention, and Treatment.” Journal of Clinical Oncology : Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 34 (35): 4225–30. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.69.4638.

Pettersson, A., and R. M. Tamimi. 2012. “Breast Fat and Breast Cancer.” Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 135 (1): 321–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-012-2186-2.

Riggio, A. I., K.E. Varley, and A. L. Welm. 2021. “The Lingering Mysteries of Metastatic Recurrence in Breast Cancer.” British Journal of Cancer 124 (1): 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-020-01161-4.

Sanjosé, S., M. Brotons, and M. A. Pavón. 2018. “The Natural History of Human Papillomavirus Infection.” Human Papilloma Virus in Gynaecology 47 (February): 2–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2017.08.015.

Sharma, G. N., R. Dave, J. Sanadya, P. Sharma, and K. K. Sharma. 2010. “Various Types and Management of Breast Cancer: An Overview.” Journal of Advanced Pharmaceutical Technology & Research 1 (2): 109–26.

Sharpless, N. E., and D. S. Singer. 2021. “Progress and Potential: The Cancer Moonshot.” Cancer Cell 39 (7): 889–94.

Siegel, R. L., K. D. Miller, N. S. Wagle, and A. Jemal. 2023. “Cancer Statistics, 2023.” CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 73 (1): 17–48. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21763.

Sjögren, L. L., L. S. Mørch, and E. Løkkegaard. 2016. “Hormone Replacement Therapy and the Risk of Endometrial Cancer: A Systematic Review.” Maturitas 91 (September): 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.05.013.

Snijders, P. J. F., R. D. M. Steenbergen, D. A. M. Heideman, and C. Meijer. 2006. “HPV-Mediated Cervical Carcinogenesis: Concepts and Clinical Implications.” The Journal of Pathology 208 (2): 152–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/path.1866.

Stewart, C., C. Ralyea, and S. Lockwood. 2019. “Ovarian Cancer: An Integrated Review.” Gynecology Oncology 35 (2): 151–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2019.02.001.

Sun, Y., Z. Zhao, Z. Yang, F. Xu, H. Lu, Z. Zhu, W. Shi, J. Jiang, P. Yao, and H. Zhu. 2017. “Risk Factors and Preventions of Breast Cancer.” International Journal of Biological Sciences 13 (11): 1387–97. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.21635.

Sung, H., J. Ferlay, R. L. Siegel, M. Laversanne, I. Soerjomataram, A. Jemal, and F. Bray. 2021. “Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries.” CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 71 (3): 209–49. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660.

Turkoz, F. P., M. Solak, I. Petekkaya, O. Keskin, N. Kertmen, F. Sarici, Z. Arik, T. Babacan, Y. Ozisik, and K. Altundag. 2013. “Association between Common Risk Factors and Molecular Subtypes in Breast Cancer Patients.” The Breast 22 (3): 344–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2012.08.005.

Wright, J.C., Prigot, A., Wright, B.P., Weintraub, S. and Wright, L.T., 1951. An evaluation of folic acid antagonists in adults with neoplastic diseases. Journal of the National Medical Association 43 (4): 211.-240.

Wright, J.C., Cobb, J.P., Gumport, S.L., Golomb, F.M. and Safadi, D., 1957. Investigation of the relation between clinical and tissue-culture response to chemotherapeutic agents on human cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 257 (25):1207-1211.

Xu, X., Ling C., M. Nunez-Smith, M. Clark, and J. D. Wright. 2023. “Racial Disparities in Diagnostic Evaluation of Uterine Cancer among Medicaid Beneficiaries.” JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 115 (6): 636–43. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djad027.

Suggested Readings

“The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer” by Siddhartha Mukherjee – This Pulitzer Prize-winning book provides a comprehensive history of cancer research and treatment, shedding light on the broader context of cancer understanding and management.

“Radical Remission: Surviving Cancer Against All Odds” by Kelly A. Turner – This book explores cases of individuals who have experienced complete remission from cancer, including some women-specific stories. It delves into the factors that may contribute to extraordinary healing.

“Breast Cancer: What You Should Know (But May Not Be Told) About Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment” by Anne McTiernan – Dr. Anne McTiernan, a renowned breast cancer researcher, provides an informative and accessible guide that covers various aspects of breast cancer, including prevention strategies and treatment options.

“Crazy Sexy Cancer Tips” by Kris Carr – Kris Carr and Sheryl Crow, a cancer survivor herself, Carr shares her personal journey and provides practical advice for women facing cancer. Her book offers insights into coping with the emotional and physical challenges of the disease.

“Bald Is Better with Earrings: A Survivor’s Guide to Getting Through Breast Cancer” by Andrea Hutton – Written by a breast cancer survivor, this book is a candid and often humorous account of the author’s journey through diagnosis, treatment, and recovery.

“Cancer Hacks: A Holistic Guide to Overcoming Your Fears and Healing Cancer” by Elissa Goodman – This book offers a holistic approach to dealing with cancer, emphasizing nutrition, mindset, and lifestyle changes that can complement traditional medical treatments.

“It’s Not About the Bra: Play Hard, Play Fair, and Put the Fun Back into Competitive Sports” by Brandi Chastain and Daniel Paisner – This book by soccer star Brandi Chastain discusses her experience with breast cancer and her determination to stay active and positive throughout her treatment.

Interesting Podcast

The Doctor’s Art Decoding Cancer (with Dr. Harold Varmus)