6 Gender and Sexuality

STUDENT LEARNING OUTCOMES

At the end of this chapter you should be able to:

- Contrast gender and biological sex

- Identify different terms to describe gender identity

- Explain why gender and sexuality are often conflated but should be considered separately

- Discuss sexual orientation and its connection to identity

- Describe the connection between the hormones, the brain, and sexuality

- Describe the sexual response cycle in females and discuss the hallmarks of each stage

- Define sexual dysfunction in women and recall some of its causes

A traditional view of gender and biological sex

A traditional view of gender and biological sex

Around the 20th week of pregnancy, many expectant parents in the United States decide to hold a “gender reveal party”. A quick Google search of “gender reveal party ideas” produces a myriad of things one can do such as hiring a baker to fill a cake with pink or blue icing, filling an opaque balloon with pink or blue confetti, or filling a large cardboard box with helium-filled pink or blue balloons that will float out when opened. Notice they involve a binary code (pink or blue) for the big reveal. These parties reassert the standard idea of binary gender, girls are pink and boys are blue (Gieseler 2018). In the United States, this code can be traced back to Alcott’s (1868) Little Women: where “Amy ties a pink bow and a blue bow on Meg’s twins Daisy and Demi so people will know the difference between the girl and the boy”, (Frassanito and Pettorini 2008). However, it did not stick until the 1940s when children’s clothing was mass-produced rather than home-made, and manufacturers and retailers understood how they could sell twice as many goods with a binary code, thereby reducing gender-neutral options (Paoletti 2012). Over the next 40 years trends shifted but the pink-girl-blue-boy code became the norm from the 80s onward. Nevertheless, as straightforward as a pink-blue code may seem, it is misleading because people falsely assume that there are only two genders and that an infant’s gender identity is the same as their biological sex.

Separating gender from biological sex

Defining biological sex

Biological sex is related to gender but they are two very different things. To understand sex we must first tease the concept of a person’s gender apart from a person’s biological sex. As noted in the chapter on the Evolution of Sex, if we stick to sexually reproducing multi-celled organisms, biological sex can be fundamentally defined by anisogamy, with females producing large eggs and males producing small sperm. Using this simple definition of biological sex allows a clear distinction between individuals of the female sex and those of the male sex. This helps us to understand how differences in anatomy, physiology, and behavior between sexes would arise and persist (Parker 2014).

Why not just use sex chromosomes to define sex? When biological sex is defined by the presence/absence of sex chromosomes with those having XX chromosomes versus an XY to define the female and male respectively, then key groups are left (i.e. crocodilians or turtles that exhibit environmental sex determination). This definition also excludes birds and some insects whose females exhibit heterogametic sex (ZW) chromosomes. Furthermore, nearly half of all plant species lack sex chromosomes altogether. When we consider the role of genes involved in sex determination it is apparent that key genes are important for determining a particular sex but not in defining it (see the chapter on the Genetics of Sex).

Furthermore, female and male-associated traits have complex genetic architectures, meaning multiple genes interact with one another and the environment to produce them. So, although the fundamental anisogamy-definition of biological sex is simple, the actual realization of biological sex is still quite complicated. Anisogamy-defined sex is useful because it spans different groups of sexually reproducing organisms without constraint and allows for the flexibility of diversity observed in disparate groups.

Defining gender

Gender is a deeply personal and psychological aspect of a person’s identity(identity is who a person thinks they are). Gender is multidimensional, “shaped by individual characteristics, family dynamics, historical factors, and social and political context” (Tatum 2000). A person’s gender identity determines how people view themselves in the cultural normative context (Wood and Eagly 2009), and “provides an important basis for their interactions with others” (Steensma et al. 2013). Therefore a person’s gender is separate from a person’s sex because gender is how a person feels, what they perceive about their biological sex, and how they want to behave relative to their biological sex.

Social ideas about gender are connected to biological sex because femininity and masculinity (attributes regarded as characteristic of women and men) are directly impacted by sex hormones. Many feel that gender and sex are “mutually constitutive categories that must be considered in tandem” (Schudson, Beischel, and van Anders 2019). Adding to the confusion is the fact that in the United States (as is the case with most countries), we are assigned a biological sex (female or male), at birth based on our external genitalia. It is automatically assumed that this assignment extends to one’s gender.

However, as Bittner and Goodyear-Grant (2017) note, “(1) sex and gender are distinct, even if they overlap and (2) that gender is at least partly explained by socialization, even if it is also biologically influenced”. Gender is comprised of different components as follows: a) physiological/ bodily aspects (sex); (b) gender identity or self-defined gender; (c) legal gender; and (d) social gender in terms of norm-related behaviors and gender expressions (Lindqvist, Gustafsson Sendén, and Renström 2021). Each of these components can change over a lifetime. Moreover, because one’s gender identity can change over time, and can be fluid, strict binary assignment disregards whether or not our personal-held gender identification matches that “assignment”. Distress can result from “incongruence between experienced/ expressed gender and assigned gender” known as gender dysphoria (Steensma et al. 2013).

When considering gender identity we must be respectful and inclusive with our language and promote an understanding of the diversity of human experiences. Gender identities can vary beyond the binary categories of male and female. The following terminology is used by some to describe gender identities (Rioux et al. 2022).

Commonly Used Gender Identity Terms

Agender: not having a gender.

Bigender/Trigender/Pangender: individuals who feel they are two, three, or all genders. They may shift between these genders or be all of them at the same time.

Boi: a female-bodied individual who expresses or presents themselves in a culturally/stereotypically masculine, particularly boyish way.

Butch: a masculine gender expression which can be used to describe people of any gender.

Cisgender: a term used to describe an individual whose gender identity aligns with the one typically associated with the sex assigned to them at birth.

Dead name: the birth name of somebody who has changed their name. Most commonly attributed to transgender individuals, but can be attributed to anyone who has changed their name.

Femme: a feminine gender expression used to describe people of any gender.

Gender nonconforming: a person who views their gender identity as one of many possible genders beyond strictly female or male.

Gender diverse: an umbrella term for people who expand notions of gender expression and identity beyond societal gender norms.

Gender expression: the way a person publicly expresses their gender to others through appearance and mannerisms (e.g., the way one dresses, talks, acts, moves).

Gender fluid: when a person does not identify solely as male or female, and their gender identity changes over time.

Intergender: An individual who feels their gender identity is between man and woman, both man and woman, or outside of the binary of man and woman.

Non-binary: when a person may identify as being both a man and woman, somewhere in between, or as falling completely outside these categories. Non-binary can also be used as an umbrella term encompassing identities such as agender by gender genderqueer or gender fluid.

Transgender: an umbrella term for people whose gender identity and or expression is different from cultural expectations based on the sex they were assigned at birth.

Transition: a broad definition is the process transgender people may go through to become comfortable in terms of their gender.

Sensitivity about gender is needed

Whereas sex is the result of billions of years of evolution gender is not, and in this modern era humans should be free to express their gender identity how best fits them. Yet, that is often not the case. Gender-diverse individuals face “substantial discrimination, prejudice, and bias, resulting in social inequalities and stigma” (Drabish and Theeke, 2021). As Tatum (2000) points out those who consider themselves members of the dominant social group take their identity for granted, “their inner experience and outer circumstance are in harmony with one another, and the image reflected by others is similar to the image within”. Not everyone experiences this advantage. The struggle for trans people in particular is real, with several research studies documenting that 40% or more of those identifying as trans have attempted suicide at least once in their lifetime (Dickey and Budge 2020). In a recent review by Chan et al.,(2023) it was reported that discrimination and inequality of healthcare for transgender athletes was noted in over a third of those surveyed and that they had significantly higher rates of suicide than cis-gendered athletes.

Furthermore, respecting pronouns (she/him/they) is gender-affirming and a failure to do so is a form of misgendering and can be damaging to the individual (Yarbrough 2018). Always “listen for and respect a person’s self-identified terminology” (Human Rights Campaign website) so that people may feel empowered and seen. Sensitivity regarding gender is necessary to create a more inclusive, equitable, and respectful society. It acknowledges the diversity of gender identities, promotes the well-being of individuals, and helps protect the rights of those who do not conform to traditional gender norms.

Separating gender from sexuality and sexual orientation

Human sexuality is complex and comprises much more than sexual acts alone. It is a combination of attraction, thoughts, desires, fantasies, and sexual roles. According to the American Psychological Association (2023), an individual’s sexuality encompasses emotional, romantic and/or sexual attraction to another. Similar to gender, sexuality also refers to an individual’s sense of personal and social identity but it is based on “attractions, related behaviors, and membership in a community of others who share those attractions and behaviors.”

The terms sexual identity and sexual orientation are often used interchangeably however Moser (2016) clearly defines sexual identity as “how individuals define themselves sexually. It may or may not describe their actual sexual behavior, fantasy content, or to which sexual stimuli they respond”. In comparison, sexual orientation is defined as a type of romantic and/or sexual interest toward persons of the same gender or biological sex, persons of the other gender or biological sex (heterosexual), or both genders/biological sex. Sexual orientation is flexible, complex, and multifaceted and reflects the diversity of sexual, affectional, and erotic attractions and love toward persons of the same gender, another gender, or both genders (Garnets 2002).

Because sexual orientation is part of one’s identity and sexual preferences it is directly connected to both sex and gender and the two are often automatically combined. Part of the conflation of sexuality and gender comes from the fact that commonly used sexual orientation identity terms are based on a gender binary. Everyone’s experiences of sexuality are unique and it’s crucial to support individuals, embracing and expressing their authentic selves, free from stereotypes and prejudices.

Commonly Used Sexual Orientation Terminology

Heterosexual or straight (female-male preference)

Homosexual (same-sex preference) – Lesbian (female-female preference) and Gay (male-male preference)

Bisexual (both male and female preference)

Asexual (preference for neither) – a person who does not experience sexual attraction.

Ace – umbrella term to describe a lack of, varying, or occasional experiences of sexual attraction.

Pansexual – a person who is sexually, emotionally, romantically, or spiritually attracted to others, regardless of biological sex, gender expression (of masculine or feminine characteristics), or sexual orientation” (Rice, 2015).

Queer – once used as a slur this term has been reclaimed by the LQBT community it is “currently used to acknowledge the non-normative” … queer is used as an “umbrella term to describe the non-heterosexual” (Panfil 2020).

Questioning – a term used to describe those who are in a process of discovery and exploration about their sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, or a combination thereof.

LGBTQ+ – The acronym for lesbian, gay, bi, trans, queer, questioning and ace.

According to Morandini, Dacosta, and Dar-Nimrod (2021), there is a “problem with viewing sexual orientation as existing in binary gay/straight categories…because it leads gay/lesbian individuals to be seen as more fundamentally different”. Furthermore, it is not reflective of many people’s experiences. Kinsey, Pomeroy, and Martin (1948) first studied sexuality in men and found evidence of sexuality being more of a continuum rather than individuals adhering to rigid completely heterosexual or homosexual preferences. Moreover, sexuality can be fluid. Ventriglio and Bhugra (2019) define sexual fluidity as “changes in sexual identity and sexuality as a result of internal and external factors.” Thelwall et al. (2023) report academic researchers use several different terminologies, with “this plurality probably reflecting differing needs.”

The brain, genes, and sexuality

Sexuality and sexual orientation development involve complex interactions among a network of distinct endogenous and exogenous factors. The heart is a vital organ; thus, historic metaphorical language has treated it as the source of emotions, desire, and wisdom. However, neuroscience has helped us to understand that feelings are a neurological mechanism impacted by hormones and connected to the brain (van Wingen et al. 2011). According to Bakker (2021), several morphological and neurochemical sex differences are induced by hormones specifically during the perinatal period “…are thought to be at the basis of sex differences in the control of reproductive functions”.

During early embryonic development, the fetus is exposed to testosterone and estrogens that bind to steroid hormone receptors in the brain (McCarthy et al. 2009). Margaret McCarthy is a leading neuroscientist who has made significant discoveries related to gender differences and the brain. Her seminal research focuses on the influence of steroid hormones on the developing brain with a special emphasis on understanding the cellular mechanisms that establish sex differences.

Q&A with Dr. Margaret M. McCarthy Ph.D.

Director, University of Maryland – Medicine Institute of Neuroscience Discovery

What drew you to studying the brain and specifically the sexual dimorphism of the brain? I started with a keen interest in animal behavior from the perspective of evolutionary biology (most of my colleagues started as psychologists), and that naturally led to the brain which at the time was truly the last frontier in that we knew so little. I always remind students that the discipline of neuroscience, if you base it on the first meeting of the Society for Neuroscience, is only a bit over 50 years old whereas chemistry and physics are hundreds of years old. As I became more interested in how evolution acted on organisms via behavioral expression this naturally led to reproduction as it is directly tied to fitness. During my master’s thesis, I studied maternal behavior in mice as well as infanticidal behavior committed by both males and females to enhance their reproductive fitness, this was a paradigm shift from the view that infanticide was a pathology created by domestication in the laboratory. From there I extended my work to mating behavior during my PhD and postdoc. I was always fascinated by the Sexually Dimorphic Nucleus of the Preoptic Area (SDN) as an anatomical structure that could mediate sex differences in behavior and the last experiment I did as a postdoc involved using antisense oligonucleotides to manipulate its size. I then vowed if I was lucky enough to get my very own lab I would commit to studying how sex differences in the brain form at the time they are established as a means to discover novel mechanisms.

What have you enjoyed most about your research? It would be hard to pinpoint any one thing. From the scientific perspective, I have enjoyed that we have generated fundamental new knowledge about how the brain is built, and this was achieved by comparing males and females as they develop, I liken it to using sex as a contrast agent. Since we are one of only a few labs that study sex differences as they happen there has been a lot of low-hanging fruit and so we have made some surprising discoveries of roles for the immune system and inflammatory signaling molecules that are not related to illness, just normal brain development. Outside of science, I have enjoyed the incredible travel I have been able to do because I’m a scientist, I have been to places I never would have gone if not for the invitation and have made friends all over the world, including China, Japan, Brazil, Mexico, Canada, Iran, Slovenia, Italy, Germany, France, Spain and Ireland, I’m sure there are more I am forgetting. Lastly, because I have been successful in research I have also been able to influence the research enterprise through leadership positions both in scientific societies, as a reviewer and editor of journals, and as a director of graduate education and chair of a department at my home institution. Not only does this let me participate in deciding the direction of research, but I also get to promote the careers of trainees, both my own and others. Nothing is more fun than the day a student defends their thesis or a postdoc gets a job, these are fulfilling moments.

What do you find most challenging about your career? Again so many things. One is the work never ends and the criticism never stops. It never gets easier to read the critiques of your manuscript or grant proposal, especially when it is anonymous and you often do not get a chance to reply, just a REJECT. It is hard to see students go through this as well but it is a big part of the discipline and so you have to be able to deal with it. As to the work never stopping, not only is there always more to do, but there is always someone who is doing more and better than you. I know scientists are not supposed to be competitive but of course we are. Sometimes I think I would be happier as an organic berry farmer.

What advice do you have for future women scientists? This is the hardest to answer as there is no one panacea to the challenges women face. It has been disheartening to see how many women start out and are so enthusiastic and then leak out of the pipeline. The pandemic devastated the women in my lab and seemed to energize the men. Of course, childcare is one of the biggest challenges but so is the relentless stress so my, somewhat cheesy, advice is to remember that science is a fast-moving train and your job is to stay on the train every day. Some days you will be hanging onto the caboose by your fingertips, but other days you will be the engineer, so just stay on cause once the train leaves the station without you, it is gone, and you can’t get back on (overly dramatic I know). In some ways this is freeing, there is no deciding whether to take a few years off and raise the kids till the first grade or go part-time, you have to commit fully and so the lack of choices is a benefit. I never felt guilty about working when raising my kids, despite my mother-in-law’s best efforts. The benefits of academic science are that you are not punching a clock and so outside of teaching you have enormous day-to-day flexibility to do things like take the kids to the doctor, go on field trips, etc. and this is a real plus. Last bit of advice, try not to take anything personally, it is about the science, and even if it is not tell yourself it is, unless there is clear evidence of bias or harassment, in that case, fight like hell.

What role do hormones play?

Rodent studies have provided some insight into the role hormones play in sexually dimorphic behavior. For instance, in hamsters, the amygdala has many androgen receptors, and amygdala-dependent behaviors (important for learning) are influenced by testosterone (Wood and Newman 1995). Hormone activity in the brain of adult mice is essential for reproductive behavior. The role of nuclear ERα estrogen receptors in the reproductive behavior of female mice was demonstrated by Ogawa et al. (1998) who created knock-out mice lacking these receptors and observed that these females lacked sexual receptivity. In humans, sex-specific differences in the strength of binding of ERα have been observed with females having significantly greater activity in their ventromedial nucleus (VMN), a specific nucleus within the hypothalamus (Liu and Shi 2015).

Additionally, adult female and male brains have a sexually dimorphic region within the hypothalamus called the sexually dimorphic nucleus of the preoptic area (SDN-POA) (Hofman and Swaab 1989). It is hypothesized that this region along with the third interstitial nucleus of the anterior hypothalamus (INAH-3) “may be partially processing sex stimuli associated with basic attractions to others” (Wang, Wu, and Sun 2019). High concentrations of both estradiol and testosterone have been observed in the human female hypothalamus and POA (Bixo et al. 1995). For both women and men, testosterone has an activating effect on sexual interest (also known as libido) (Davis and Tran 2001).

In addition to circulating blood hormone levels impacting gene expression, other environmental factors trigger epigenetic control of genes involved in receptivity. Multiple genes on several chromosomes are involved. A recent genome-wide association study (GWAS) reported by Ganna et al. (2019), revealed that numerous loci underlie sexual behavior in both sexes and found five autosomal loci to be significantly associated with same-sex sexual behavior. Not only does the presence of sex-specific genes matter, but how the genes are regulated also helps understand sex-dependent sensitivity to stimuli (Forger 2016). Research is still needed to help us better understand this complex topic, specifically on the epigenetic control of gene expression and the impact of environmental factors on the establishment of sexuality.

The female sexual response

When it comes to sexual activity humans are among just a handful of animals that do not limit sexual activity to reproduction. Like humans, bonobos, white-faced capuchins, and dolphins have been observed to engage in “social sex” that involves mating beyond the breeding season, homosexual activity, and mating with other species (Manson, Perry, and Parish 1997; Markowitz, Markowitz, and Morton 2010). Unlocking the complex psychology and physiology of the sexual behavior of humans is an ongoing endeavor. Two instrumental research studies that laid the foundation of this field and challenged societal norms were led by Alfred Kinsey and William Masters & Virgina Johnson.

Alfred Kinsey was one of the first scientists to extensively study sexual behavior in women. He and his associates surveyed and interviewed thousands of individuals from across the United States, compiling a comprehensive dataset published in his book “Sexual Behavior in the Human Female” (1953) (a follow-up to his first study on male sexual behavior). One ground-breaking area that Kinsey investigated, in particular, was the female orgasm where he dispelled myths and misconceptions surrounding women’s ability to experience pleasure and orgasm, arguing that women and men shared the physiological capacity to respond to sexual stimulation. In 1966 another revolutionary study that delved more deeply into the physiological side of sexual behavior was published in the book “Human Sexual Response” by Masters and Johnson. This landmark work fundamentally changed how society and scientists approached the study and understanding of the human sexual response (Gerhard 2000).

Masters and Johnson (1966) directly observed women and men engaging in masturbation and sexual activity, enabling them to measure the physical and physiological responses of participants, including heart rate, blood pressure, skin tone changes, muscle tension, and respiratory rates. They found that a woman’s clitoris is the main erogenic zone (an area that can produce sexual arousal when stimulated). They also discovered that the main difference between women and men was a woman’s capacity for multiple orgasms, which men lack.

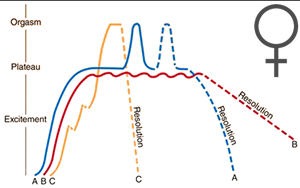

Masters and Johnson identified a pattern shared among both women and men which they called the sexual response cycle, divided into four successive phases (EPOR): Excitement, Plateau, Orgasm, and Resolution, depicted in the image below. During the response cycle, two key physiological mechanisms were observed (both in genitalia and throughout the body): vasocongestion (increased blood flow into the organs so that the tissues become engorged and usually undergo a color change) and myotonia (increased muscular tension that occurs both voluntarily and involuntarily). The following describes the hallmarks of each phase however bear in mind that this cycle represents a composite of potential physiological responses and varies greatly from person to person. There are also important psychological elements to each stage.

Hallmarks of the EPOR response cycle

Excitement phase – during this phase, physiological and psychological changes happen when an individual becomes sexually aroused in response to sexual stimuli or desire. Most women reported clitoral stimulation alone established the excitement phase. The following are hallmarks of the excitement phase:

- Vasocongestion: Blood flow increases to the genital area, leading to engorgement of the swelling of the clitoris as the corpora cavernosa becomes engorged with blood. The uterus becomes engorged and moves upward. The vaginal walls expand and transducate from the vaginal walls, increasing vaginal lubrication. The labia minora swell and their color darkens.

- Nipple Eection: The areola enlarges and swells, and the breast size increases.

- Increased Heart Rate: The heart rate increases due to heightened arousal and the release of adrenaline.

- Flushed Skin: Increased blood flow can cause the skin to appear flushed or reddened, particularly in the neck area.

- Increased Respiration: Breathing becomes more rapid and shallow, partly due to increased oxygen demand during arousal.

- Myotonia: Muscles throughout the body, including those in the genital area, may become tense and contract as a result of increased blood flow and arousal.

- Bartholin’s Gland Secretion: small amounts of mucoid material may be excreted late in the excitement phase.

Plateau phase – during this phase, “sexual tensions are intensified and the duration is dependent upon the stimuli employed combined with the individual drove for culmination”. The following are hallmarks of the plateau phase:

- Vulvar Erection: the bulbs become swollen, and the uterus is further elevated.

- Clitoris Retraction: the body and glans of the clitoris retract from their non-stimulated overhanging position and withdraw deep under the prepuce carrying the labia minora and the suspensory ligament along toward the pubic synthesis; although no longer visible, the clitoris is still responsive to stimulation.

- Sex Flush Spreads: the labia majora continues to show more color changes and there is further swelling of the areola and the flush spreads over the breasts and the shoulders (varying among women).

- Myotonia Continues: further tightening of the muscles occurs.

- Increased Heart Rate: further elevation in heart rate occurs

Orgasm phase – This is the culmination of sexual arousal. During this phase (limited to a few seconds), the vasocongestion and myotonia are released after an involuntary climax is reached. There is great variability in the intensity and duration of the orgasmic experience. Sherlock et al. (2016) surveyed women and found that orgasm variation is contingent upon sexual skill. The following are hallmarks of the orgasm phase:

- Rhythmic Contractions: the muscles that make up the vaginal wall and vulva undergo contractions. This can also happen in the anal sphincter. The intensity and number of contractions vary.

- Sex Flush Peak: flush reaches peak intensity.

- Total-Body Involvement: some voluntary muscular control is lost as the involuntary contraction of multiple muscle groups occurs (e.g. pelvic floor muscles; deep abdominal muscles).

Resolution phase – orgasm is directly followed by an involuntary period of tension loss returning the individual to an unstimulated state. “Women have the response potential of returning to another orgasmic experience from any point in the resolution phase”. The following are hallmarks of the resolution phase:

- Blood Drains: blood is released and drains out of engorged tissues.

- Skin Color Returns: the coloration of skin returns to pre-excitement state, sex flush disappears.

Individuals may experience variations in the intensity and duration of each phase and the sexual response cycle is not always linear. People can move back and forth between phases or skip certain phases depending on the circumstances. Furthermore, the EPOR model is simply a model to provide a point of reference, not a rule, and varies among individuals. There is also a notable difference between women and men. For example, a woman can experience multiple orgasms during the O phase before resolution (Masters and Johnson, 1966).

The EPOR model has been refined over the years with different models allowing for increased complexity (reviewed by Wylie and Mimoun, 2009). Kaplan (1974) proposed a three-phase model composed of desire, arousal, and orgasm whereas Basson proposed a circular sexual response pattern (2001). More recently, the sexual tipping point (STP) model (Perelman, 2009) allows for greater complexity and variability among women and states that sex is both mental and physical and that the mind and body both inhibit and excite sexual response. The specific “tipping point” for a sexual response is determined by multiple factors at any given moment or circumstance.

Female sexual dysfunction

Women may experience difficulties during one or more stages of the sexual response cycle and if these cause distress or prevent the individual from feeling satisfied with the sexual activity they are classified as sexual dysfunction (Chen et al. 2013). The prevalence of sexual dysfunction in women appears to be high. Hayes et al. (2006) analyzed data from multiple studies and found that 64% of women reported having sexual difficulty with 62-89% persisting for at least several months. They also found a striking pattern across different studies: reports of sexual desire difficulties are the most common, followed by orgasm difficulties (known as anorgasmia), arousal difficulties, and pain associated with sexual activity (referred to as dyspareunia).

What causes sexual dysfunction in women?

Faubion and Rullo (2015) provide a review of the topic noting that the causes of female sexual dysfunction are multifaceted, including biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors. Problems with desire can stem from medical issues that directly or indirectly impact function such as vascular disease, cancer, bladder problems, and neuromuscular disorders. Vaginismus, a condition that causes spasms from fear of penetration, can result in painful sex. Antidepressants that have serotonin-enhancing abilities can have an inhibitory effect on sexual function, impacting desire, excitement, and orgasm. Hormonal changes throughout one’s life may hinder sexual function. Testosterone levels gradually decline as women age and menopause is marked by a sharp decline in estrogen levels that directly impacts vaginal lubrication.

Treatment for sexual dysfunction

The first step to treatment involves identifying underlying issues. Therefore a comprehensive medical and psychosocial history is highly recommended and there are multiple treatment modalities depending on the specific issue (Basson et al. 2010). The treatment may be as simple as using a safe over-the-counter water-based vaginal lubricant. Or it may require prescription medication. Two drugs to treat low sexual desire in premenopausal women have been recently given FDA approval: fibanserin (Addyi) a daily pill, and bremelanotide (Vyleesi) an injectable that can be used up to eight times per month.

Sexuality is a normal and healthy part of the human experience. Individuals must have the autonomy and support to explore and understand their sexuality in a way that is safe, consensual, and fulfilling. Open communication, education, and a non-judgmental approach to one’s own and others’ sexuality can help demystify and navigate the complexities of human sexual experience. We must also keep in mind that there is no “right” way to be sexual; what matters most is that individuals have a healthy and satisfying sexual experience that aligns with their values and desires.

Think, Pair, Share

In your own words describe the difference between gender and biological sex.

Drabish and Theeke (2021) report transgender people experience “inequalities and stigma…which negatively impacts health outcomes and changes in the psychological and physical health of transgender people”. Why would this be happening in a healthcare setting where physicians are supposed to adhere to the Hippocratic oath which states: I will keep patients from harm and injustice?

We discussed the physical and physiological changes that women experience during the four stages of the sexual response cycle. What psychological changes might a woman experience during each stage?

What do you think sexual dysfunction is for men, for women? How common is it for women and why might people not discuss it as often as they do for men?

Deeper Questions

How does the profound disconnection between one’s inner sense of self and the external perceptions of their gender in gender dysphoria challenge our understanding of identity, authenticity, and the intricate interplay between the physical body, social constructs, and the essence of who we truly are?

It is hypothesized that levels of particular sex hormones in the bloodstream might increase or decrease a person’s level of sexual desire so would a transdermal testosterone and estrogen patch alone increase libido?

Women have a greater capacity for orgasm yet they seem to have more difficulty experiencing orgasm than men. Why?

Key Terms

Biological sex

Bisexual

Cisgender

Gender

Gender diverse

Gender nonconforming

Heterosexual

Homosexual

Myotonia

Nonbinary

Nucleus of the preoptic area

Pansexual

Queer

Sexual response cycle

Sexual dysfunction

Transgender

Vaginismus

Ventromedial nuclei

Vasocongestion

References

Bakker, J.. 2021. “Chapter 18 – Kisspeptin and Neurokinin B Expression in the Human Hypothalamus: Relation to Reproduction and Gender Identity.” In Handbook of Clinical Neurology, edited by Dick F. Swaab, Felix Kreier, Paul J. Lucassen, Ahmad Salehi, and Ruud M. Buijs, 180:297–313. Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-820107-7.00018-5.

Basson, R., M. E. Wierman, J. Van Lankveld, and L. Brotto. 2010. “REPORTS: Summary of the Recommendations on Sexual Dysfunctions in Women.” The Journal of Sexual Medicine 7 (1_part_2): 314–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01617.x.

Bittner, A., and E. Goodyear-Grant. 2017. “Sex Isn’t Gender: Reforming Concepts and Measurements in the Study of Public Opinion.” Political Behavior 39 (4): 1019–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-017-9391-y.

Bixo, M., T. Bäckström, B. Winblad, and A. Andersson. 1995. “Estradiol and Testosterone in Specific Regions of the Human Female Brain in Different Endocrine States.” The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 55 (3–4): 297–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/0960-0760(95)00179-4.

Chan, A.S.W., Choong, A., Phang, K.C. et al. 2024. “Societal Discrimination and Mental Health Among Transgender Athletes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. BMC Psychology 12 (24) https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01493-9

Charlie R., A. Paré, K. London-Nadeau, R. Juster, S. Weedon, S. Levasseur-Puhach, M. Freeman, L. E Roos, and L. M Tomfohr-Madsen. 2022. “Sex and Gender Terminology: A Glossary for Gender-Inclusive Epidemiology.” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 76 (8): 764. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2022-219171.

Chen, C. Yen-Chin L., Li-Hsuan C. Yuan-Hsiang C., Fang-Fu R., Wei-Min L., and P. Wang. 2013. “Female Sexual Dysfunction: Definition, Classification, and Debates.” Taiwanese Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 52 (1): 3–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tjog.2013.01.002.

Davis, S. R., and J. Tran. 2001. “Testosterone Influences Libido and Well Being in Women.” Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism 12 (1): 33–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1043-2760(00)00333-7.

Dickey, L. M., and Stephanie L. Budge. 2020. “Suicide and the Transgender Experience: A Public Health Crisis.” American Psychologist 75 (3): 380–90. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000619.

Drabish, K., and L. A. Theeke. 2021. “Health Impact of Stigma, Discrimination, Prejudice, and Bias Experienced by Transgender People: A Systematic Review of Quantitative Studies.” Issues in Mental Health Nursing 43(2):111–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2021.1961330

Faubion, S. S., and J. E. Rullo. 2015. “Sexual Dysfunction in Women: A Practical Approach.” American Family Physician 92 (4): 281–88.

Forger, N. G. 2016. “Epigenetic Mechanisms in Sexual Differentiation of the Brain and Behaviour.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 371 (1688): 20150114. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0114.

Frassanito, P., and B. Pettorini. 2008. “Pink and Blue: The Color of Gender.” Child’s Nervous System 24 (8): 881–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-007-0559-3.

Ganna, A., K.J. H. Verweij, M. G. Nivard, R. Maier, R. Wedow, A.S. Busch, A. Abdellaoui, et al. 2019. “Large-Scale GWAS Reveals Insights into the Genetic Architecture of Same-Sex Sexual Behavior.” Science 365 (6456): eaat7693. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aat7693.

Garnets, L. D. 2002. “Sexual Orientations in Perspective.” Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 8 (2): 115–29. https://doi.org/10.1037/1099-9809.8.2.115.

Gerhard, J.. 2000. “Revisiting ‘The Myth of the Vaginal Orgasm’: The Female Orgasm in American Sexual Thought and Second Wave Feminism.” Feminist Studies 26 (2): 449–76. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178545.

Gieseler, C.. 2018. “Gender-Reveal Parties: Performing Community Identity in Pink and Blue.” Journal of Gender Studies 27 (6): 661–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2017.1287066.

Hayes, R. D., C. M. Bennett, C. K. Fairley, and L.Dennerstein. 2006. “What Can Prevalence Studies Tell Us About Female Sexual Difficulty and Dysfunction?” The Journal of Sexual Medicine 3 (4): 589–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00241.x.

Hofman, M. A., and D. F. Swaab. 1989. “The Sexually Dimorphic Nucleus of the Preoptic Area in the Human Brain: A Comparative Morphometric Study.” Journal of Anatomy 164 (June): 55–72.

Kinsey, A. 1953. Sexual Behavior in the Human Female. W. B. Saunders Company.

Kinsey, A., W. B. Pomeroy, and C. E. Martin. 1948. Sexual Behavior in the Human Male. Saunders.

Lindqvist, A., M. Gustafsson Sendén, and E. A. Renström. 2021. “What Is Gender, Anyway: A Review of the Options for Operationalising Gender” 12 (4): 332–44.

Liu, X., and H. Shi. 2015. “Regulation of Estrogen Receptor α Expression in the Hypothalamus by Sex Steroids: Implication in the Regulation of Energy Homeostasis.” Edited by Mario Maggi. International Journal of Endocrinology 2015 (September): 949085. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/949085.

Manson, J. H., S. Perry, and A. R. Parish. 1997. “Nonconceptive Sexual Behavior in Bonobos and Capuchins.” International Journal of Primatology 18 (5): 767–86. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026395829818.

Markowitz, T. M., W. J. Markowitz, and L. M. Morton. 2010. “Chapter 8 – Mating Habits of New Zealand Dusky Dolphins.” In The Dusky Dolphin, edited by Bernd Würsig and Melany Würsig, 151–76. San Diego: Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-373723-6.00008-4.

Masters, W. H., and V. E. Johnson. 1966. Human Sexual Response. Little, Brown.

McCarthy, M. M., A. P. Auger, Tr.L. Bale, G. J. De Vries, G. A. Dunn, N. G. Forger, E. K. Murray, B. M. Nugent, J. M. Schwarz, and M. E. Wilson. 2009. “The Epigenetics of Sex Differences in the Brain.” The Journal of Neuroscience : The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience 29 (41): 12815–23. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3331-09.2009.

Morandini, J. S., L. Dacosta, and I. Dar-Nimrod. 2021. “Exposure to Continuous or Fluid Theories of Sexual Orientation Leads Some Heterosexuals to Embrace Less-Exclusive Heterosexual Orientations.” Scientific Reports 11 (1): 16546. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-94479-9.

Moser, C.. 2016. “Defining Sexual Orientation.” Archives of Sexual Behavior 45 (3): 505–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0625-y.

Ogawa, S., V. Eng, J. Taylor, D. B. Lubahn, K.S. Korach, and D. W. Pfaff. 1998. “Roles of Estrogen Receptor-α Gene Expression in Reproduction-Related Behaviors in Female Mice**This Work Was Supported by the Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation (to S.O.), the University of Missouri-Columbia Molecular Biology Program (to D.B.L.), and NIH Grant HD-05751 (to D.W.P.).” Endocrinology 139 (12): 5070–81. https://doi.org/10.1210/endo.139.12.6357.

Panfil, V. R. 2020. “‘Nobody Don’t Really Know What That Mean’: Understandings of ‘Queer’ among Urban LGBTQ Young People of Color.” Journal of Homosexuality 67 (12): 1713–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2019.1613855.

Paoletti, J. B. 2012. Pink and Blue: Telling the Boys from the Girls in America. Indiana University Press.

Parker, G. A. 2014. “The Sexual Cascade and the Rise of Pre-Ejaculatory (Darwinian) Sexual Selection, Sex Roles, and Sexual Conflict.”

Schudson, Z. C., W. J. Beischel, and S. M. van Anders. 2019. “Individual Variation in Gender/Sex Category Definitions.” Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity 6 (4): 448.

Sherlock, J. M., M. J. Sidari, E. A. Harris, F. K. Barlow, and B. P. Zietsch. 2016. “Testing the Mate-Choice Hypothesis of the Female Orgasm: Disentangling Traits and Behaviours.” Socioaffective Neuroscience & Psychology 6 (1): 31562. https://doi.org/10.3402/snp.v6.31562.

Steensma, T. D., B. P.C. Kreukels, A.L.C. de Vries, and P. T. Cohen-Kettenis. 2013. “Gender Identity Development in Adolescence.” Puberty and Adolescence 64 (2): 288–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2013.02.020.

Tatum, B. D. 2000. “The Complexity of Identity: Who Am I.” Readings for Diversity and Social Justice 2: 5–8.

Thelwall, M., T. J. Devonport, M. Makita, K. Russell, and L. Ferguson. 2023. “Academic LGBTQ+ Terminology 1900-2021: Increasing Variety, Increasing Inclusivity?” Journal of Homosexuality 70 (11): 2514–38.

Ventriglio, A., and D. Bhugra. 2019. “Sexuality in the 21st Century: Sexual Fluidity.” East Asian Archives of Psychiatry 29 (1): 30–34.

Wang, Y., H. Wu, and Z. S. Sun. 2019. “The Biological Basis of Sexual Orientation: How Hormonal, Genetic, and Environmental Factors Influence to Whom We Are Sexually Attracted.” Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology 55 (October): 100798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yfrne.2019.100798.

Wingen, G.A. van, L. Ossewaarde, T. Bäckström, E.J. Hermans, and G. Fernández. 2011. “Gonadal Hormone Regulation of the Emotion Circuitry in Humans.” Neuroactive Steroids: Focus on Human Brain 191 (September): 38–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.04.042.

Wood, R. I., and S. W. Newman. 1995. “The Medial Amygdaloid Nucleus and Medial Preoptic Area Mediate Steroidal Control of Sexual Behavior in the Male Syrian Hamster.” Hormones and Behavior 29 (3): 338–53. https://doi.org/10.1006/hbeh.1995.1024.

Wood, W., and A. H. Eagly. 2009. “Gender Identity.” In Handbook of Individual Differences in Social Behavior, 109–25. The Guilford Press.

Yarbrough, E. 2018. Transgender Mental Health. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing.

Suggested Reading

“The Other Big Bang: The Story of Sex and Its Human Legacy” by Eric Haag – Haag provides a thoughtful examination of the evolution for a better understanding of modern society’s notion of gender to help bend the arc of history toward gender equality.

“Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity” by Judith Butler – Judith Butler’s influential work explores the performative nature of gender and challenges traditional notions of identity and sexuality.

“Sex, Time, and Power: How Women’s Sexuality Shaped Human Evolution” by Leonard Shlain – Shlain presents a unique perspective on the evolution of sex by examining how women’s sexual biology and reproductive capabilities have influenced human history and culture.

“The Second Sex” by Simone de Beauvoir – Simone de Beauvoir’s classic feminist text delves into the construction of femininity and the historical oppression of women, providing a foundational perspective on gender.

“Whipping Girl: A Transsexual Woman on Sexism and the Scapegoating of Femininity” by Julia Serano – Julia Serano discusses the intersection of gender, sexuality, and feminism, with a focus on the experiences of trans women and the stereotypes they face.

“The Straight Mind and Other Essays” by Monique Wittig – Monique Wittig’s essays challenge conventional notions of heterosexuality and the construction of gender, offering a queer feminist perspective.

“Queer: A Graphic History” by Meg-John Barker and Julia Scheele – This graphic novel provides a concise overview of queer theory, exploring key concepts related to gender and sexuality in an accessible format.

“Sexual Fluidity: Understanding Women’s Love and Desire” by Lisa M. Diamond – Lisa Diamond’s research-based book explores the concept of sexual fluidity in women, challenging rigid definitions of sexual orientation.

“The Invisible Orientation: An Introduction to Asexuality” by Julie Sondra Decker – This book provides an introduction to asexuality and the experiences of individuals who do not experience sexual attraction.

“The ABC’s of LGBT+” by Ashley Mardell – Aimed at young adults and newcomers to LGBTQ+ topics, this book offers an accessible and inclusive introduction to gender and sexuality diversity.

“Gender and Our Brains: How New Neuroscience Explodes the Myths of the Male and Female Minds” by Gina Rippon – Gina Rippon discusses recent findings in neuroscience that challenge traditional ideas about gender differences in the brain, including the genetic factors that influence brain development.

“The Sexual Brain” by Simon LeVay – Simon LeVay, a neuroscientist, explores the biological basis of sexual orientation and how genetics and brain structure can influence sexual identity.

Interesting Podcast

Hidden Brain: The Edge of Gender