9 Infertility and Artificial Reproductive Technology

STUDENT LEARNING OUTCOMES

At the end of this chapter you should be able to:

- Define infertility

- Recall the female causes and male causes of infertility

- Describe how female factors are diagnosed

- Discuss treatments for female infertility

- Explain the different types of ART

- Define stratified reproduction

- Discuss the ethical issues surrounding ART

Infertility is a disease

Young women typically fear getting pregnant although most do not understand fertility and “often overestimate the chances of pregnancy” (Bunting, Tsibulsky, and Boivin 2013). According to the World Health Organization, approximately 18% of the adult population experience infertility, classically defined as “a disease of the male or female reproductive system defined by the failure to achieve a pregnancy after 12 months or more of regular unprotected sexual intercourse” (WHO, 2023). Infertility can be subdivided into primary and secondary infertility. Primary infertility is the inability to conceive, meaning a person has never been able to get pregnant and give birth. Secondary infertility refers to those who have gotten pregnant and given birth at least once in the past. Secondary infertility is the most common form of infertility experienced by women (Vander Borght and Wyns 2018). Described as a long-lasting and complex life crisis, infertility patients report experiencing distress, depression, anxiety and decreased quality of life (Rooney and Domar 2018). Infertility ranks as one of the greatest sources of stress in a woman’s life comparable to cancer (Baram et al. 1988). Jennings (2010) interviewed several women struggling with infertility and one comment from a woman named Nancy stood out:

…a lot of women they grow up and they play with their baby dolls and they always have that. They take that for granted, that it [becoming a mother] will always be there and when it’s not, it’s the most life-changing thing that I think a woman can go through…

There is a falsely perceived connection between a woman’s sense of herself as a woman and her body’s “failure” of not being able to give birth (Poddar, Sanyal, and Mukherjee 2014). Despite the prevalence of infertility, most infertile women “do not share their story with family or friends, thus increasing their psychological vulnerability” (Rooney and Domar 2018), likely due to an internalized feeling of inadequacy. Loftus and Andriot (2012) interviewed 40 infertile women and one common theme they found was that these women could not see themselves as complete women. They believed that they had failed to achieve the goal of motherhood and “interactions with other women only add to their pain by highlighting their inability.”

What causes infertility?

Infertility is a multifaceted disease linked to both singular and combined female and male factors. In approximately 50% of heterosexual couples female factors are responsible, and in 20% male factors are responsible, however for a significant percentage, there is no clear cause (Shreffler, Greil, and McQuillan 2017). Unexplained infertility is diagnosed when standard investigations fail to reveal any obvious barrier to conception (Maheshwari, Hamilton, and Bhattacharya 2008).

Female factors of infertility

- Age is the single most important female factor. This is because the ovarian reserve becomes depleted over time. Between the ages of 18 and 26 years, women experience a peak in fertility, this begins to decline after age 27 and drops significantly after 35 (Dunson, Colombo, and Baird 2002). Women in industrialized and high-income countries like the United States are delaying childbirth. According to the 2020 United States National Survey, the average age at first birth increased to 27 years (Martin, Hamilton, and Osterman 2021). This is a significant jump when compared to the 1970s when the age at first birth was 21 years old (Matthews and Hamilton 2002). This tracks with changing gender norms, with an increased emphasis on post-secondary education and career development for women. Women also may be delaying childbearing due to economic factors or partner issues.

- Underlying medical conditions that may damage the fallopian tubes, and interfere with ovulation or fertilization can cause infertility such as:

- adhesions caused by pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) or prior pelvic surgery

- endometriosis

- polycystic ovarian syndrome

- premature ovarian failure

- uterine fibroids

- cervical problems (structural abnormalities and or abnormal cervical mucus production

- Diagnosis of these underlying conditions is made from an evaluation of the woman’s medical history, physical examination, and various imaging techniques for examining the uterus and fallopian tubes. According to Panchal and Nagori (2014) imaging techniques include: ultrasound (particularly saline-infusion sonohysterography), hysterosalpingography (visualization of the Fallopian tubes), hysteroscopy (visualization of the uterus), and laparoscopy (visualization of the pelvic organs). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the imaging study of choice as it can detect tumors as small as 3-5 mm. Combinations of these imaging procedures may be used to confirm diagnoses.

- Factors that impact the HPG (hypothalamus-pituitary-gonad) axis:

- disorders of the endocrine system causing imbalances of reproductive hormones

- excessive weight gain or excessive weight loss can impact estrogen levels

Diagnosis of HPG problems is made from an evaluation of the woman’s medical history, physical examination, tracking of the menstrual cycle, measuring basal body temperature, monitoring cervical mucus, measuring mid-luteal progesterone levels, progestin challenge test to demonstrate edometrium’s ability to respond, and an endocrine evaluation (Koroma and Stewart 2012).

- Exposure to environmental stressors can cause infertility:

- alcohol consumption

- smoking

- STIs (sexually transmitted infections) are a leading cause of infertility: PID can be caused by Chlamydia trachomatis and Gonorrheae that can result in abscess formation, adhesions, scarring, tubal blockade, tubal damage, ectopic pregnancy

- chemotherapy cancer treatment

- exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemical compounds

- emotional stress

Male factors of infertility

Babakhanzadeh et al. (2020) report the following factors responsible for male infertility:

- Physical obstruction of the tract impacts ejaculation and or impairment of sperm. Caused by:

- STIs such as gonorrhea and chlamydia can lead to obstruction in the epididymis

- enlargement of sperm vessels (varicocele) in the scrotum

- Factors that impact the HPG (hypothalamus-pituitary-gonad) axis:

- disorders of the endocrine system causing imbalances of reproductive hormones

- Exposure to environmental stressors that impact sperm production and quality

- alcohol consumption and smoking

- obesity

- chemotherapy cancer treatment

- endocrine-disrupting chemical compounds

- anabolic steroid use

- emotional stress

- Age is also a factor in men, with fertility rates declining significantly in their mid-thirties (Dunson et al., 2002).

Diagnosis of conditions is made from an evaluation of the man’s medical history, a physical examination, and a semen analysis

How is infertility treated?

One of the first lines of treatment is to address underlying emotional stress. Domar et al. (2011) report increased pregnancy rates for those engaging in mind/body therapy. This type of practice involves meditation and relaxation. As Hajela et al. (2016) point out mind/body therapy rejuvenates the mind and clarifies thoughts helping in maintaining healthy body chemistry, and providing patience to undergo the challenge of infertility treatments.” An additional study by (Clifton et al. 2020) showed “a reduction in distress and an increase in pregnancy rates for those participating in an internet-based mind/body program as compared to those in the quasi-control wait-list group.”

Q&A with Dr. Alice Domar, Ph.D.

Associate Professor of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Biology,

Beth Isreal Deaconess Medical Center

What drew you to studying different ways to help women with the stress of health-related issues, specifically infertility and IVF? Two things led me to specifically research the relationship between stress and infertility. The first was that my parents went through infertility; it took them seven years to conceive my older sister and another five to conceive me. So throughout my childhood, my mother talked about how awful it was to have infertility while all her friends and relatives were having many children. There were few treatment options back then, and zero sources of emotional support, so it was an awful time for her. The second reason is that I have always wanted to be a pioneer, to be the first at what I dedicated my career to. And no one was doing anything to relieve the distress of women with infertility. I had read an abstract of a small study that included 14 women; half received several sessions of cognitive-behavioral therapy and half did not. Four of the seven in the CBT group conceived and none of the controls did. Which sent me in the direction of applying CBT to women with infertility from a research and clinical perspective.

What have you enjoyed most about your research? I love the fact that my research is always unique and that the clinical application of what I am researching helps relieve the intense emotional pain of those struggling with infertility, as well as significantly increasing their chances of conceiving. I also appreciate the global interest in these approaches and the fact that I have the opportunity to train healthcare professionals from around the world on how to apply the clinical program to their patients.

What do you do to try to balance work with life? It is certainly easier now that my two children are in their 20’s. When they were little, I didn’t work full-time which did put a strain on my career goals, but I put my family first. When I went back to full-time, I always worked from home two days/week. That way I could walk them to school in the mornings. I tried to take my family with me on as many work trips as I could. I also wanted to be a good role model for my daughters, to demonstrate that a woman could have a busy and fulfilling career. Now I take long walks during the day when I don’t have meetings, my husband comes with me on as many work trips as possible, and I try to minimize evening and weekend commitments.

What advice do you have for women who want a career in science? Go for it! No matter what anyone may have said to you, women are just as capable in the sciences as men are. Follow your talents and passion. Don’t listen to others, listen to your own gut feeling. Find a mentor who believes in you. I had a college professor who had a massive impact on my career- he truly believed in me. It was his idea that I go into health psychology instead of medicine and it was exactly the right career path for me.

When an underlying cause is identified it is then directly treated when possible. For example, a woman with an ovulatory disorder may be prescribed clomiphene citrate (Clomid), an antiestrogen that competitively binds to ERs resulting in increased GnRH; or Pergonol (purified FSH-LH) to induce ovulation (Lindsay and Vitrikas 2015). If no cause has been identified, the first line of treatment for heterosexual couples is counseling on the timing and position of intercourse with improvements in coital practice by having intercourse every two days during ovulation. Over-the-counter urinary luteinizing hormone kits can be used to indicate the midcycle luteinizing hormone surge that precedes ovulation by one to two days.

Intrauterine insemination (IUI) can be utilized when there are sperm motility issues or cervical issues. This is the placement of sperm directly into the woman’s uterus using a thin catheter or syringe, near the time of ovulation, to facilitate fertilization. Oftentimes ovulation will be stimulated as discussed above, then ultrasonography is performed to enable the visualization of follicular development to the point of ovulation. The mature follicles typically measure from 17 to 25 mm in average inner dimension.

The optimal follicular size before triggering ovulation in intrauterine insemination cycles with clomiphene citrate or letrozole was found to be in the 23–28 mm range (Palatnik et al. 2012). If another year passes without pregnancy, those with unexplained infertility may choose Artificial Reproductive Technology.

Artificial Reproductive Technology (ART)

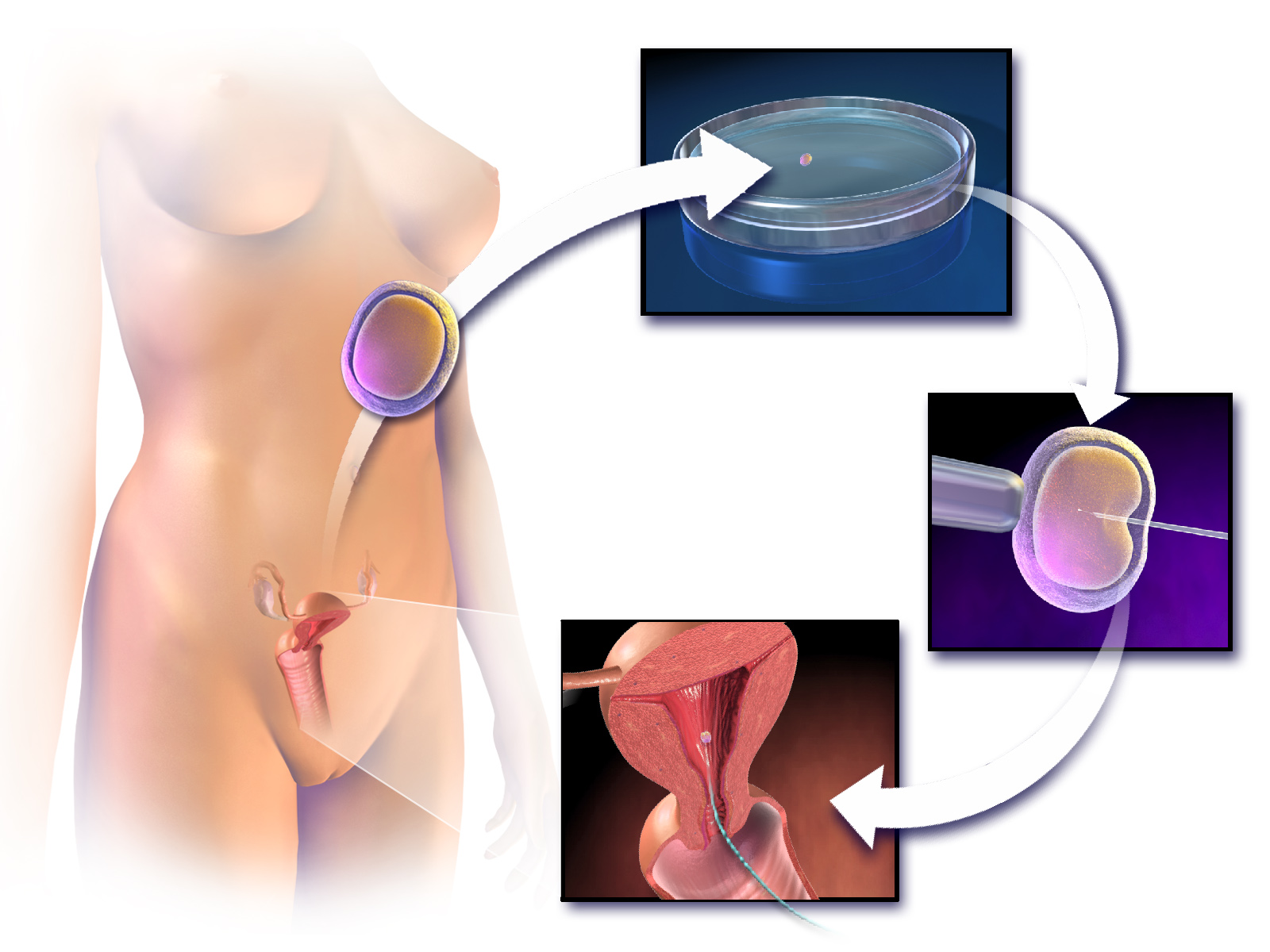

On July 25th, 2023, the world celebrated the 45th anniversary of the birth of the first ‘test-tube baby’, bringing in the new age of ART (Steptoe and Edwards 1978). Since then significant advancements have been made in ART such as the development of the EmbryoScope, an embryo incubator with time-lapse imaging (Sciorio, Thong, and Pickering 2018). ART is a broad term used to describe fertility treatments in which either eggs or embryos are handled. “In general, ART procedures involve surgically removing eggs from a woman’s ovaries, combining them with sperm in the laboratory, and returning them to the woman’s body or donating them to another woman” (CDC website on ART). ART can be costly, consuming, and highly stressful. The risk of miscarriage increases significantly for infertile women undergoing assisted reproduction (Agenor and Bhattacharya 2015).

Common ART procedures

In vitro fertilization (IVF) – the fertilization of eggs and sperm outside the body in a laboratory dish. IVF involves “controlled ovarian stimulation, oocyte retrieval under ultrasound guidance, insemination, embryo culture, and transcervical replacement of embryos at cleavage or blastocyst stage” (Pandian, Gibreel, and Bhattacharya 2015). The resulting embryos are then implanted into the woman’s uterus. There is an elevated risk of multiple pregnancies with IVF which threatens the health of both mother and fetus. A joint committee opinion from the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) and Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology strongly recommends limiting the number of embryos implanted per cycle based on age (one for those under the age of 37, three for those aged 38-40 and four for those over the age of 41 years) (2017). According to the CDC’s 2020 Fertility Clinic Success Rates Report, the likelihood of a live birth from IVF is 23%. The outcome is dependent on many factors such as the mother’s age, those between 20 – 30 years of age have the best IVF outcomes, (Yan et al. 2012), and whether or not frozen or fresh embryos are used, Zargar et al. (2021) report a significant increase in live birth rates when frozen embryos are used.

Intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) – a single sperm cell is injected directly into an egg to facilitate fertilization in a dish. This technique is often used when there are male infertility issues (poor sperm motility) or in cases of low oocyte yields (Palermo et al. 2017). See the image below.

Gamete intrafallopian transfer (GIFT) – the direct transfer of both sperm and eggs into the woman’s fallopian tube allowing fertilization to occur within the body (in vivo) (Asch et al. 1986). Multiple eggs are collected thanks to artificial follicular stimulation and then mixed with treated sperm. The combined gametes are placed in the fallopian tube using laparoscopy.

Zygote intrafallopian transfer (ZIFT) is similar to GIFT as ZIFT involves the transfer of a fertilized embryo (zygote) into the fallopian tube. Weissman et al. (2013) demonstrated increased success over IVF using ZIFT, attributing the success to the fallopian tube participating in key functions involved in fertilization and embryogenesis. However, traditional GIFT and ZIFT are not commonly used because they require anesthesia and laparoscopic surgery, but recent advancements in noninvasive micro-robotic GIFT/ZIFT using nano techniques have the potential to improve outcomes (Nauber et al. 2023).

Gestational Surrogacy with IVF – eggs from a donor are fertilized through IVF, and the embryos are implanted in a surrogate mother (not genetically related), also known as a gestational carrier, that will carry and give birth to a baby on behalf of another individual or couple.

How many people use ART in the United States?

The latest statistics provided by the CDC are from 2020 (Sunderam et al. 2020) in which a total of 203,119 ART procedures were undertaken (range: 196 in Alaska to 26,028 in California). This resulted in 73,831 live-birth deliveries and 81,478 infants born (range: 84 in Wyoming to 10,620 in California), representing 2% of all infants born. While ART may be an answer to infertility, it does continue to focus on the infertility of heterosexual couples, and some find that it discourages viable alternatives like child-free living and adoption.

What does the future of ART look like?

While there has been a steady increase in the age of infertile women seeking ART over the past twenty years, proactive fertility care is the new trend (van de Wiel 2022). More and more women are seeking to avoid future infertility by using planned oocyte cryopreservation however in 2018 the Ethics Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine strongly recommended that women “are informed about its efficacy, safety, benefits, and risks, including the unknown long-term health effects for offspring”. The recently established Prelude Fertility Network company (initiated with $200 million in start-up funding), is an example of this shift in which individuals embrace ART at younger ages (Gleicher, Kushnir, and Barad 2019). It is a company “focused on proactive fertility care to improve people’s chances of having healthy babies when they’re ready” in a four-step process: fertility preservation through freezing of oocytes and sperm at peak fertility (ages 20s to early 30s); embryo creation in the laboratory when the time has come to start a family, and the embryos undergo genetic screening before transfer.

Socioeconomic status, race, and sexuality impact infertility treatment

It is very important to stress that all individuals and couples should have the right to decide the number, timing, and spacing of their children, and as such addressing infertility is an “important part of realizing the right of individuals and couples to found a family” (WHO, 2023). Globally, the WHO recognizes that “inequities and disparities in access to fertility care services adversely affect the poor, unmarried, uneducated, unemployed and other marginalized populations.” In the United States, Dongarwar et al. (2022) found that non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic women were approximately 70% less likely to utilize any form of infertility treatment. There are several sociodemographic factors contributing to this disparity. Black women report incidences of racism at IVF clinics while attempting to conceive using ART (Davis 2020) and they have lower IVF success rates when compared to White women (Seifer, Sharara, and Jain 2022).

Additionally, women and couples of lower socioeconomic status in all racial groups are having a difficult time overcoming the financial barriers to treatment. For example, the average cost of a single cycle of IVF (ovarian stimulation, egg retrieval, and embryo transfer) ranges from $15,000 to $30,000 (Forbes, 2023). In the United States, over 14% of the adult population age 19-44 lack health care insurance altogether and more often than not, fertility services are not covered by public or private insurers. Furthermore, homosexual couples and unpartnered individuals often encounter discriminatory practices, being denied health insurance coverage for fertility treatments granted to their heterosexual counterparts. Of note is a recent class action lawsuit filed in a Federal New York court by a lesbian couple (Goidel and Caplan) who claim “Aetna Inc. has a discriminatory health insurance policy that, on its face, engages in sex discrimination by denying LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, or non-binary) individuals equal access to fertility treatment” (Goidel v. Aetna Inc.).

This creates a “stratified” state of reproduction whereby privileged individuals fortunate enough to be able to afford ART are empowered compared to those in lower income brackets (Greil, McQuillan, and Slauson-Blevins 2011). Furthermore, this has caused some in the US to engage in ‘reproductive tourism’ traveling to other cheaper countries which often lack safety regulations and engage in questionable practices (Deonandan, 2015).

Think, Pair, Share

In your own words discuss why the general population has limited knowledge regarding infertility.

Why might women find infertility to be as stressful as having cancer?

Although male factors can cause infertility as much as female factors, why is there a greater focus on women when it comes to causes of infertility?

Oocyte cryopreservation may have potential repercussions for future children and for mothers who choose pregnancy at older age. What are they?

Deeper Questions

What are the pros and cons of including ART in medical insurance coverage?

What ethical implications are there regarding “proactive fertility” centers?

For some infertile women, ART can “transform infertility from a private pain to a public, prolonged crisis” (Whiteford and Gonzalez 1995). What societal changes need to happen to mitigate the discomfort women feel surrounding this experience?

International surrogacy, the act of infertile clients traveling internationally to engage the paid services of foreign surrogates to carry their babies to term, has some unique ethical challenges. How might they be overcome?

Key Terms

ART

Gestational surrogacy

ICSI

IUI

IVF

Primary infertility

Proactive fertility care

Reproductive tourism

Secondary infertility

References

Agenor, A., and S. Bhattacharya. 2015. “Infertility and Miscarriage: Common Pathways in Manifestation and Management.” Women’s Health 11 (4): 527–41. https://doi.org/10.2217/WHE.15.19.

Asch, R. H., J. P. Balmaceda, L. R. Ellsworth, and P. C. Wong. 1986. “Preliminary Experiences with Gamete Intrafallopian Transfer (GIFT)**Recipient of the 1985 Squibb Award. Presented at the Forty-First Annual Meeting of The. American Fertility Society, September 28 to October 2, 1985, Chicago, Illinois.” Fertility and Sterility 45 (3): 366–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0015-0282(16)49218-6.

Babakhanzadeh, E., M. Nazari, S. Ghasemifar, and A. Khodadadian. 2020. “Some of the Factors Involved in Male Infertility: A Prospective Review.” International Journal of General Medicine 13 (December): 29–41. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S241099.

Baram, D., E. Tourtelot, E. Muechler, and K. Huang. 1988. “Psychosocial Adjustment Following Unsuccessful in Vitro Fertilization.” Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology 9 (3): 181–90. https://doi.org/10.3109/01674828809016800.

Bunting, L., I. Tsibulsky, and Jacky Boivin. 2013. “Fertility Knowledge and Beliefs about Fertility Treatment: Findings from the International Fertility Decision-Making Study.” Human Reproduction 28 (2): 385–97. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/des402.

Clifton, J., J. Parent, M. Seehuus, G. Worrall, Forehand, and A. Dormar. 2020. “An Internet-Based Mind/Body Intervention to Mitigate Distress in Women Experiencing Infertility: A Randomized Pilot Trial.” PLoS ONE 15 (3): e0229379.

Davis, D. 2020. “Reproducing While Black: The Crisis of Black Maternal Health, Obstetric Racism and Assisted Reproductive Technology.” Reprotech in France and the United States: Differences and Similarities 11 (November): 56–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbms.2020.10.001.

Deonandan, R.. 2015. “Recent Trends in Reproductive Tourism and International Surrogacy: Ethical Considerations and Challenges for Policy.” Risk Management and Healthcare Policy 8 (December): 111–19.

Domar, A. D., K. L. Rooney, B. Wiegand, E. J. Orav, M. M. Alper, B. M. Berger, and J. Nikolovski. 2011. “Impact of a Group Mind/Body Intervention on Pregnancy Rates in IVF Patients.” Fertility and Sterility 95 (7): 2269–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.03.046.

Dongarwar, D., V. Mercado-Evans, S. Adu-Gyamfi, M. Laracuente, and H. M. Salihu. 2022. “Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Infertility Treatment Utilization in the US, 2011–2019.” Systems Biology in Reproductive Medicine 68 (3): 180–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/19396368.2022.2038718.

Dunson, D. B., B. Colombo, and D. D. Baird. 2002. “Changes with Age in the Level and Duration of Fertility in the Menstrual Cycle.” Human Reproduction 17 (5): 1399–1403. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/17.5.1399.

Gleicher, N, V A Kushnir, and D H Barad. 2019. “Worldwide Decline of IVF Birth Rates and Its Probable Causes.” Human Reproduction Open 2019 (3): hoz017. https://doi.org/10.1093/hropen/hoz017.

Greil, A., J. McQuillan, and K. Slauson-Blevins. 2011. “The Social Construction of Infertility.” Sociology Compass 5 (8): 736–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9020.2011.00397.x.

Hajela, S., S. Prasad, A. Kumaran, and Y. Kumar. 2016. “Stress and Infertility: A Review.” International Journal of Reproduction, Contraception, Obstetrics and Gynecology 5 (4): 940–43.

Jennings, P. K. 2010. “‘God Had Something Else in Mind’: Family, Religion, and Infertility.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 39 (2): 215–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891241609342432.

Koroma, L., and L. Stewart. 2012. “Infertility: Evaluation and Initial Management.” Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health 57 (6): 614–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1542-2011.2012.00241.x.

Lindsay, T. J., and K. R. Vitrikas. 2015. “Evaluation and Treatment of Infertility.” American Family Physician 91 (5): 308–14.

Loftus, J., and A. L. Andriot. 2012. “‘That’s What Makes a Woman’: Infertility and Coping with a Failed Life Course Transition.” Sociological Spectrum 32 (3): 226–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/02732173.2012.663711.

Maheshwari, A., M. Hamilton, and S. Bhattacharya. 2008. “Effect of Female Age on the Diagnostic Categories of Infertility.” Human Reproduction (Oxford, England) 23 (3): 538–42. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dem431.

Martin, J. A., B. E. Hamilton, and M. J. K. Osterman. 2021. “Births in the United States, 2020.” 418. NCHS Data Brief. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. https://dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc:109213.

Matthews, M. S., and B. E. Hamilton. 2002. “Mean Age of Mother, 1970-2000.” National Vital Statistics Report 51 (1).

Nauber, R., S. R. Goudu, M. Goeckenjan, Martin Bornhäuser, Carla Ribeiro, and Mariana Medina-Sánchez. 2023. “Medical Microrobots in Reproductive Medicine from the Bench to the Clinic.” Nature Communications 14 (1): 728. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-36215-7.

Palatnik, A., E. Strawn, A. Szabo, and P. Robb. 2012. “What Is the Optimal Follicular Size before Triggering Ovulation in Intrauterine Insemination Cycles with Clomiphene Citrate or Letrozole? An Analysis of 988 Cycles.” Fertility and Sterility 97 (5): 1089-1094.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.02.018.

Palermo, G. D., C. L. O’Neill, S. Chow, S. Cheung, A. Parrella, N. Pereira, and Z. Rosenwaks. 2017. “Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection: State of the Art in Humans.” Reproduction 154 (6): F93–110. https://doi.org/10.1530/REP-17-0374.

Panchal, S., and C. Nagori. 2014. “Imaging Techniques for Assessment of Tubal Status.” Journal of Human Reproductive Sciences 7 (1): 2–12. https://doi.org/10.4103/0974-1208.130797.

Pandian, Z., A. Gibreel, and S. Bhattacharya. 2015. “In Vitro Fertilisation for Unexplained Subfertility.” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, no. 11. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003357.pub4.

Poddar, S., N. Sanyal, and U. Mukherjee. 2014. “Psychological Profile of Women with Infertility: A Comparative Study.” Industrial Psychiatry Journal 23 (2): 117–26. https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-6748.151682.

Rooney, K. L., and A. D. Domar. 2018. “The Relationship between Stress and Infertility.” Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 20 (1): 41–47. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2018.20.1/klrooney.

Sciorio, R., J. K. Thong, and S. J. Pickering. 2018. “Comparison of the Development of Human Embryos Cultured in Either an EmbryoScope or Benchtop Incubator.” Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics 35 (3): 515–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-017-1100-6.

Seifer, D. B., F. I. Sharara, and T. Jain. 2022. “The Disparities in ART (DART) Hypothesis of Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Access and Outcomes of IVF Treatment in the USA.” Reproductive Sciences 29 (7): 2084–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43032-022-00888-0.

Shreffler, K. M., A. L. Greil, and J. McQuillan. 2017. “Responding to Infertility: Lessons From a Growing Body of Research and Suggested Guidelines for Practice.” Family Relations 66 (4): 644–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12281.

Steptoe, P. C., and R. G. Edwards. 1978. “Birth after the Reimplantation of a Human Embryo.” Lancet (London, England) 2 (8085): 366. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(78)92957-4.

Sunderam, S., D. M. Kissin, Y. Zhang, A. Jewett, S. L. Boulet, L. Warner, C. D. Kroelinger, and W. D. Barfield. 2020. “Assisted Reproductive Technology Surveillance – United States, 2018.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries (Washington, D.C. : 2002) 71 (December): 1–19. http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss7104a1external icon.

Vander Borght, M., and C. Wyns. 2018. “Fertility and Infertility: Definition and Epidemiology.” The Role of Biomarkers in Reproductive Health 62 (December): 2–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2018.03.012.

Weissman, A., E. Horowitz, A. Ravhon, H. Nahum, A. Golan, and D.Levran. 2013. “Zygote Intrafallopian Transfer among Patients with Repeated Implantation Failure.” International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 120 (1): 70–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.07.018.

Whiteford, Li. M., and L. Gonzalez. 1995. “Stigma: The Hidden Burden of Infertility.” Guilt, Blame and Shame: Responsibility in Health and Sickness 40 (1): 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(94)00124-C.

Wiel, L.. 2022. “Disrupting the Biological Clock: Fertility Benefits, Egg Freezing and Proactive Fertility Management.” Reproductive Biomedicine & Society Online 14 (March): 239–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbms.2021.11.004.

Yan, J., K. Wu, R. Tang, L. Ding, and Z. Chen. 2012. “Effect of Maternal Age on the Outcomes of in Vitro Fertilization and Embryo Transfer (IVF-ET).” Science China Life Sciences 55 (8): 694–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11427-012-4357-0.

Zargar, M., S. Dehdashti, M. Najafian, and P. Moradi Choghakabodi. 2021. “Pregnancy Outcomes Following in Vitro Fertilization Using Fresh or Frozen Embryo Transfer.” JBRA Assisted Reproduction 25 (4): 570–74. https://doi.org/10.5935/1518-0557.20210024.

Suggested Reading

“It Starts with the Egg: How the Science of Egg Quality Can Help You Get Pregnant Naturally, Prevent Miscarriage, and Improve Your Odds in IVF” by Rebecca Fett – Rebecca Fett discusses the role of egg quality in fertility and offers evidence-based recommendations to improve natural conception and IVF success rates.

“Inconceivable: A Woman’s Triumph over Despair and Statistics” by Julia Indichova – Julia Indichova shares her personal journey of overcoming infertility through holistic approaches and provides hope and inspiration to others facing similar challenges.

“The Whole Life Fertility Plan: Understanding What Affects Your Fertility to Help You Get Pregnant When You Want To” by Kyra Phillips and Jamie Grifo – This book explores the various factors that can impact fertility and offers guidance on lifestyle changes to enhance fertility.

“IVF: A Patient’s Guide” by Rebecca Matthews and Dan Nayot – Written by a fertility specialist and a patient, this book provides a comprehensive overview of the IVF process, including what to expect and how to prepare.

“Not Broken: An Approachable Guide to Miscarriage and Recurrent Pregnancy Loss” by Lora Shahine – Lora Shahine, a reproductive endocrinologist, offers insights into miscarriage and recurrent pregnancy loss, including causes, treatment options, and emotional support.

“Conquering Infertility: Dr. Alice Domar’s Mind/Body Guide to Enhancing Fertility and Coping with Infertility” by Alice D. Domar and Alice Lesch Kelly – Dr. Alice Domar, a renowned expert in mind-body medicine, guides managing stress and using relaxation techniques to enhance fertility.

Interesting Podcast

The Future Conceived The impacts of IVF and other Assisted Reproductive Technologies (ART) on human reproduction with Dr Rebecca Krisher