12 Menopause and Aging

STUDENT LEARNING OUTCOMES

At the end of this chapter you should be able to:

- Describe the terminology of menopause and discuss why it is confusing

- Explain the physiological changes that occur during the menopausal transition

- Recall the different ways in which the MT impacts a woman’s health

- Describe hormone replacement therapy

- Discuss agism and the double standard women are held to

- Recall the hypothesis on how aging is controlled at the cellular level

- Explain why lifestyle choices during mid-life are the key to healthy aging

Menopause is perplexing.

Why can this part of a woman’s life be so confusing? First, there are so many different phrases and ways to refer to menopause. Some call it “the change”, others say it is a woman’s “midlife crisis”, or in a more positive light, “second spring”. But there are also confusing terms such as premenopause or perimenopause.

Second, a woman is not always certain that menopause has happened and women often do not know what to expect during this time of their lives. During this transitional period of life, a woman may experience a wide variability in symptoms and she often does not know that it is happening until it is well over. A survey of nearly 1,000 women regarding their attitudes toward menopause revealed much confusion, uncertainty, and dread (Harper et al. 2022). Part of this is due to the confusing terminology used to describe the different phases of this period of a woman’s life.

Ambikairajah, Walsh, and Cherbuin (2022) review menopause terminology. The menopause transition (MT) is the period before the final menstrual period (FMP). It is during MT when variability in the menstrual cycle is increased. Missing at least one menstrual period within the past 3 months or a variation in menstrual cycle length of 7 days or more defines the early MT. However, nearly one-fourth of women report very little change in their cycles before they stop menstruating (Hale, Robertson, and Burger 2014).

There is also what is known as perimenopause (a specific phase overlapping MT) which is the period immediately before the FMP when endocrinological, biological, and clinical features of approaching menopause commence, as well as the first year after menopause. Then there is menopause, the period after 12 consecutive months of amenorrhea. In other words, a woman has not yet actually experienced menopause until they have stopped having their period for a full year. Therefore menopause can only be known after the fact, a year or more after the the FMP. And postmenopause is referred to as the period following the FMP. FSH levels continue to rise while estrogen continues to fall until they stabilize approximately two years after the FMP (Harlow et al. 2012).

- The official definition of menopause = The WHO specifically defines menopause as the permanent cessation of menstruation resulting from the loss of ovarian follicular activity and deemed to have naturally occurred after 12 consecutive months of amenorrhea, for which no other obvious pathological or physiological causes could be determined.

- Induced menopause, is defined as the cessation of menstruation following either surgical removal of both ovaries (i.e. oophorectomy), or iatrogenic ablation of ovarian function (i.e. chemotherapy or irradiation). The result is irreversible loss of fertility (Ambikairajah et al. 2022).

Traditionally women have not usually discussed menopause, nor have they received the support needed from healthcare providers, family, or friends during this transition. A lack of education for women and understanding or empathy from their general practitioners can exacerbate their feelings of confusion and isolation (Harper et al. 2022). It is also important to bear in mind that some transgender men and non-binary or gender-diverse people might also experience menopause and are also in need of support.

When does the MT happen?

In 2001 and 2011 members of the Office of Research on Women’s Health (ORWH) of the National Institutes of Health, The North American Menopause Society (NAMS), the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM), the International Menopause Society (IMS), and the Endocrine Society came together for the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW). They were tasked with reviewing the available research and providing “consistent classification of menopause status for studies of midlife women” (Harlow et al., 2012).

STRAW produced a chronology of the ovary with stages that go from menarche at -5 to peak reproductive, -4, to late reproductive, -3, to -2 early MT, -1 late MT, 0 FMP, +1 early post-menopause and then +2, late post-menopause. The MT, FMP, and PM stages are illustrated in the figure below.

Early MT is often characterized by missed periods and fluctuations in FSH. Pre-ovulatory LH surge is diminished (downs) suggesting that the hypothalamus does not respond normally to estrogen. The late MT period is characterized by more consistently elevated FSH, and amenorrhea ≥60 days. Late MT lasts approximately 1 to 3 years (Santoro 2005). The aging of the ovary is synced with the chronological aging of the individual. Together, they influence the pace of the menopausal transition process and how long it lasts (Talaulikar 2022).

STRAW chronology of the ovary from early menopause transition (MT) to post-menopause (PM) characterized by changes in FSH levels. Image adapted from Ambikairajah, Walsh, and Cherbuin (2022).

What triggers the MT?

Depletion of oocytes due to hormonal shifts triggers MT. Each woman has a ‘‘threshold’ of oocytes below which normal ovarian function cannot be maintained” (Davis et al. 2023). This usually occurs in women over 45 years of age and can last five years or more. As the threshold approaches, inhibin declines which leads to a rise in FSH especially in the early follicular phase of the cycle which shortens the follicular phase and ramps up the follicle maturation process. The follicles appear larger but have a slower growth rate, resulting in smaller follicles being released during ovulation (Santoro et al. 2021; Davis et al. 2023). As the number of follicles decreases, longer spans of amenorrhea occur, and the late MT can be marked by more noticeable symptoms of hot flashes (VMSs), sleep issues, vaginal dryness, and mood swings. The MT can last four years or more.

Can one confirm the MT?

A single test for MT does not yet exist. However, the level of FSH can be measured if a woman is not on any type of hormonal birth control. Elevated early follicular phase FSH levels are supportive criteria for entry into STRAW stage −2, and FSH levels of >25 IU/L were also included as a supportive criterion for entry into stage −1 (Harlow et al., 2012). However FSH levels can fluctuate and are not always reliable therefore clinicians usually rely on a combination of menstrual history, age, and symptoms (Bastian, Smith, and Nanda 2003).

Perimenopause-Menopause-Postmenopause, how to know?

One of the largest and longest studies examining the menopause transition (MT) is the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). This study began in 1996 as a multisite, multiracial/ethnic, longitudinal project examining 3,302 women (42 and 52 years of age). All participants had an intact uterus and at least one ovary, were not receiving hormone therapy, were not pregnant or lactating, and had at least one menstrual period in the 3 prior months. The results of this long-term project are summarized in the textbox below. These results have been, and are continuing to be published. Thus far the combined results show that MT is much more than not having one’s period anymore, the changes associated with it have far-reaching effects.

Summary of SWAN findings (El Khoudary et al. 2019)

Menstrual cycle length and the onset of MT

- Menstrual cycle length increased beginning 7.5 years before the FMP

- Amenorrhea of 60+ days is the marker of entry into the late stage of the MT

- Smokers have both an earlier onset of the MT and a shorter total MT duration

- Black women have a longer total MT duration

Age at natural menopause

- The median age at natural menopause was 51.4 years

- Familial predisposition to early or late menopause is commonly encountered, which supports the hypothesis of genetic programming of ovarian failure

Hormonal shifts

- Estrogen (E2) and FSH levels fall and rise respectively

- Patterns of E2 declining and FSH rising were observed but not all women experienced a single pattern

- Levels of circulating E2 and FSH varied by body mass index (BMI) and race/ethnicity

Vasomotor symptoms (VMS), defined as hot flashes and night sweats

- Up to 80% reported experiencing VMS

- Black women had the highest prevalence and longest duration of VMS and were most bothered by their VMS

- Women in lower socioeconomic positions were more likely to have VMS, independent of race/ethnicity

- Frequent VMS persisted for a median of 7.4 years, with even longer durations for some women

- Recent research also links VMS to poorer cardiovascular health (Thurston 2023)

Sleep difficulties

- Increased trouble sleeping reported in perimenopausal women

- Compared to other ethnic groups, White women reported the most sleep problems and Hispanic women the least

Depression and anxiety

- Greater likelihood of experiencing high depressive symptoms in the early peri-, late peri-, or postmenopause, as compared to the premenopause

- Greater likelihood of experiencing high anxiety symptoms in the early peri-, late peri-, and postmenopause compared to premenopause; peaking in late perimenopause

Memory loss

- A temporary decline in both processing speed and verbal episodic memory during perimenopause

- The decline resolves in postmenopause

Cardiovascular health

- Sharp increases in total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and apolipoprotein (Apo)B levels within a 1-year interval surrounding the FMP

- Acceleration in LDL-C was associated with a greater risk of carotid plaque later in life in a follow-up analysis

Vaginal dryness

- Vaginal dryness and atrophy increased across the MT, from about 19% in pre-and early perimenopause to 34% in postmenopause years

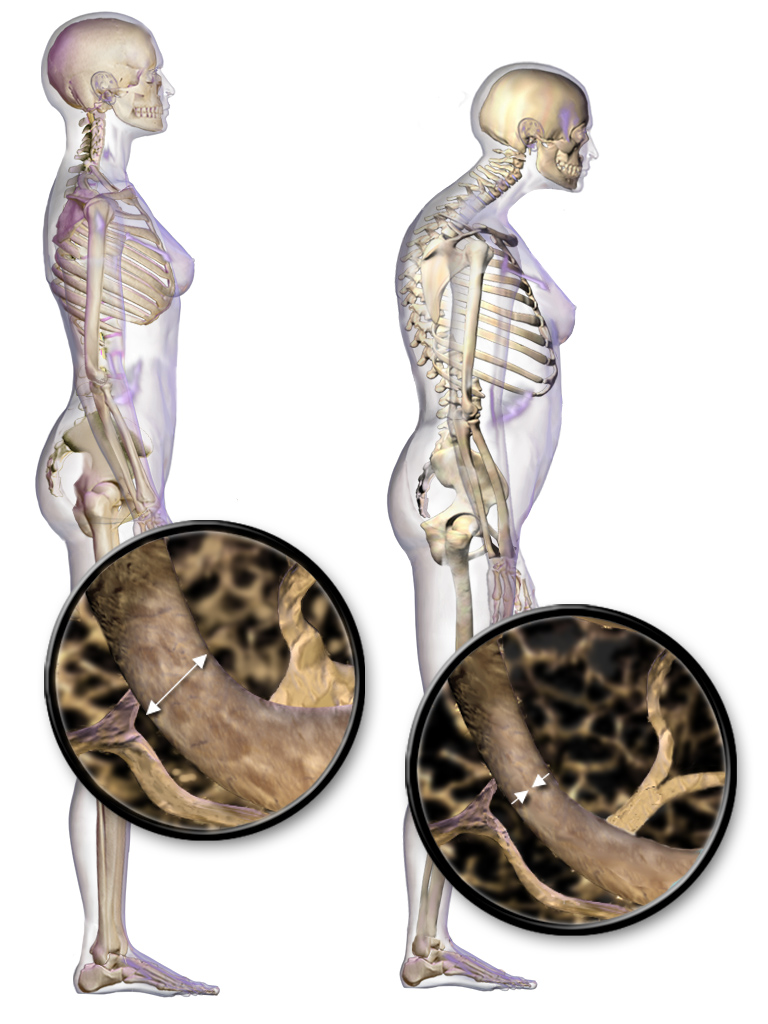

Bone density loss

- Noticeable decline in BMD (bone mass density) – 2 years before the FMP

- A drop in estrogen is one of the triggers of the greater- bone- turnover -greater-bone-loss cascade

- The rate of BMD loss commences at about 2 years post-FMP

- Cortical bone remodeling also begins 1 year before the FMP

- Fracture rates for White women are double that of Black and Asian women in the United States

Hot flashes explained

Hot flashes, or Vasomotor Symptoms (VMS), are defined as “transient periods of flushing, sweating, and a sensation of heat, often accompanied by palpitations and a feeling of anxiety sometimes followed by chills” (Kronenberg 1990). The exact cause of VMSs is yet to be completely understood. However, the underlying cause is associated with problems in the hypothalamus, the body’s thermoregulation center, and specifically hypothalamic neurotransmitters whose impaired functionality is tied to estrogen depletion (Talaulikar 2022).

During a VMS event, blood flow increases concurrent with increased body temperature in the upper torso region. The body responds with an increase in peripheral blood flow (vasodilation) to lose heat resulting in chills that bring the body temperature back to normal (Bansal and Aggarwal 2019).

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis, the most common type of bone disease, is caused by low bone mass and the disruption of bone microarchitecture can significantly increase the risk of bone fractures. Due to age-related changes primary osteoporosis usually occurs in people aged 50 years or above. Both women and men can be affected by osteoporosis, however, the decline in estrogen and progesterone during menopause significantly increases the risk of the disease. It is associated with a diminished quality of life (Ji and Yu 2015).

Sözen, Özışık, and Başaran (2017) describe the connection between menopause and osteoporosis. Bone remodeling involves the resorption of old or damaged bone, followed by the deposition of new bone material, and there is a balance between bone tissue loss by resorption and bone tissue formation. When resorption is greater than formation, bone is lost and this starts happening after puberty. Multiple factors determine the rate of bone remodeling and loss including genes, nutrition, overall health, and physical activity. Estrogen is a fundamental participant in bone remodeling and when it declines during MT this results in an imbalance in bone remodeling, thereby increasing the risk of fracture.

How is osteoporosis diagnosed?

According to Sözen, Özışık, and Başaran (2017), the WHO criterion for osteoporosis is based on the T-score. This score is determined from the results of a bone mineral density test (BMD) obtained by a central dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) that uses radiation to measure the amount of calcium in a specific area of bone, usually the femoral neck and lumbar spine (Ji and Yu 2005). T-score values between -1.0 and -2.5 are osteopenia (weakened bones), and a T-score value of -2.5 or lower is osteoporosis.

Prevention and treatment of osteoporosis

Calcium and vitamin D (V-D) is essential for bone formation therefore adequate intake of calcium and V-D, are key aspects for prevention and treatment. The Food and Nutrition Board (FNB) recommends 1,200 mg/day UL calcium for women 51+ years of age. (Institute of Medicine 2011). Regular weight-bearing and muscle-strengthening exercises are also important for the maintenance of bone density. Not all exercises are equal in their ability to ward off bone loss. Benedetti et al. (2018) found that strength training involving specifically the neck of the femur and at the lumbar spine for a minimum of 3x/week along with resistance training for the lower limbs to be most effective.

The two main prescription medications for osteoporosis are the antiresorptive agents known as bisphosphonates (BPs) e.g. Boniva, and estrogen therapy (MRT). BPs are considered a first-line-treatment and have been widely prescribed over the years to maintain BMD in the neck and spine (Compston, McClung, and Leslie 2019). MRT is highly effective at stopping bone loss and preventing fractures (Ji and Yu 2005).

Treatment for menopausal symptoms

For some women their menopausal associated symptoms are minimal and they do not require any treatment. However, for others, the symptoms can be disruptive and debilitating. Even though 84% of women surveyed (out of a total of 6,096) experienced at least one symptom with 45% noting their symptoms to be a problem (Rymer and Morris 2000), “over 85% of women in high-income countries do not receive effective, regulator-approved treatment for their menopausal symptoms” (Davis et al. 2023).

Non-prescription treatments

Although over-the-counter remedies may be more affordable and seemingly “natural” they are not regulated by the FDA and their true efficacy is questionable. Studies have been conducted on the following:

- Phyto-estrogen supplements were not effective beyond what is achieved with a placebo (Chen, Lin, and Liu 2015).

- Rheum rhaponticum (Er 731) extract was found to help reduce hot flashes (Heger et al. 2006).

- Acupuncture was found to be ineffective for hot flashes (Dodin et al. 2013).

Prescription medication for VMS

- The FDA just approved Veozah (Fezolinetant) as a non-hormonal treatment for moderate to severe VMS in menopause. According to Shaukat et al. (2023) Veozah “targets the disrupted thermoregulation underlying VMS. It modulates neural activity within the thermoregulatory center by crossing the blood-brain barrier, offering relief from hot flashes and night sweats”.

Anti-depressant treatments

- For feelings of depression and anxiety associated with MT, anti-depressants are often prescribed and “ can offer some relief for many women, none are as effective as menopause hormone therapy, and side effects such as sexual dysfunction are not uncommon” (Davis et al. 2023).

Menopause Hormone Therapy (MHT) aka HT or HRT

Many of the symptoms (eg. hot flashes, bone loss, vaginal dryness) are due to a depletion of estrogen therefore systemic estrogen therapy can alleviate those problems. “Estrogen replacement remains the most effective treatment for VMS” (Hamoda et al. 2020). The form of estrogen needed is estradiol which can be taken via transdermal patch, gel, or spray or as an oral pill. For those who still have a uterus, uterus progesterone must also be taken concurrently to protect from endometrial cancer. Those who have had a hysterectomy can take just estrogen and do not have to worry about the problems associated with the endometrium.

There are likely cardiovascular health benefits associated with taking MRT as soon as symptoms arise, usually around age 45, because it is thought that the beneficial effects of MHT are dependent on the prevention of atherosclerosis before plaque forms as opposed to in older women who already have plaque in their blood vessels (Naftolin et al. 2019).

Confusion around MHT from the WHI studies

Two major clinical studies conducted in the 1990s under the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) put a negative spin on MRT that has lasted for decades. Natari et al. (2021) reviewed the impact of the published results (WHI 2002, WHI 2004) on the perception of the safety of MRT. One study on HT use by women with an intact uterus (WHI 2002), and the other on ET use by women with a hysterectomy (WHI 2004) both terminated early because of increased breast cancer (WHI 2002) and increased stroke (WHI 2004). Widespread negative media coverage led to a significant worldside rapid decline in HT use. Yet further investigation uncovered problems with the data and a “reanalysis found that both studies were confounded by age with a ‘window of opportunity’ for cardiovascular health benefits if HT was initiated before 60 years or within ten years of menopause” (Natari et al. 2021). Subsequent investigations have shown CVD and cancer mortality did not differ between the hormone therapy and placebo arms in both WHI studies and the guidelines for MHT have been recently updated to reflect more recent findings (Davis et al. 2023). Furthermore, the excess risk associated with breast cancer is attributable to the use of combined (estrogen + progesterone) treatments, not estrogen-alone therapy (Vinogradova, Coupland, and Hippisley-Cox 2020). The duration of therapy should be based on each individual’s symptoms and personal benefit-risk evaluation.

The takeaway from the MT

Think of menopause as “a bridge to the most vital and liberated period in a woman’s life” (Sheehy 1998). This is a natural period of a woman’s life with big changes that can have consequential health ramifications. Heading into MT women need to be prepared and open to discuss the changes their bodies experience. This is also a time when one needs to focus on optimizing their health because it is “the gateway to healthy aging for women” (Davis et al. 2023).

Women, our bodies change drastically in comparison to men. We’re going through menopause. We’ve got a lot going on, and I don’t think we’ve done enough to understand what aging means for women’s bodies: What are we supposed to look like? How are we supposed to feel? We’re not talking about that enough. I’m 56 with a 56-year-old-body, and I love my body. – Michelle Obama

Aging

You cannot live without aging

We are often afraid of getting old because of the unnatural emphasis by the media and culture on youth. Social media, advertising, television, movies, and print media create an unrealistic ideal of permanent youth and beauty. Saucier (2004) comments “women are constantly bombarded with visual images of young women and ads promising youthful looks forever.” In the United States a culture of ageism, especially against women, remains (Chrisler, Barney, and Palatino 2016). The well-known notion of a ‘double standard of aging’ coined fifty years ago by famed author Susan Sontag (Sontag 1972) suggests that an aging woman is judged more harshly than an aging man persists and must be changed. As women enter middle age, the physical changes in their appearance can be striking and they need help in acknowledging changes…and dealing with the emotions associated with these changes (Saucier 2004). We must embrace old age and recognize the significant contributions older women make to society. Dolly Parton speaks on aging as something to not personally focus on: “I don’t think about my life in terms of numbers. First of all, I ain’t never gonna be old because I ain’t got time to be old. I can’t stop long enough to grow old.”

Humans are fortunate compared to their wild counterparts who typically do not live long enough to get old. Aging is accompanied by gradual changes in most body systems. Defined as “a progressive loss of function accompanied by decreasing fertility and increasing mortality” (Kirkwood and Austad 2000). There is a a great deal of variability in aging with some people living relatively independently into their 90s and others living not as long. The average life span of a woman in the United States is 79 years (Arias et al. 2022). In general, women live longer than men whose average life span is 72 years. This gender gap in life expectancy is due to both biological and sociocultural factors.

The process of aging is complex and not yet understood. A network of genes and epigenetic controls along with environmental impacts affect aging (Pal and Tyler 2016).

There are three main hypotheses regarding aging

- Senescence hypothesis – Senescence, long-term cell-cycle arrest, occurs due to excessive intracellular or extracellular stress or damage. This can be due to random mutations accumulating over time, or through continued shortening of chromosomes through replication, eventually depleting our capacity for maintenance and resilience (Dodig, Čepelak, and Pavić 2019). The dominant explanation for this is a DNA replication-dependent shortening of telomeres (Ogrodnik 2021).

- Somatic mutation hypothesis – the life span is limited by cancer rather than a loss of functionality and the cancer is a result of mutations in somatic cells (Wolf 2021)

- Program hypothesis – aging is regulated by a biological clock with specific “genetic mechanisms regulating the pace of aging” (de Magalhães and Church 2005).

Addressing the challenges and opportunities presented by an aging global population is necessary. A national census report (2020) found a 36% increase in people aged 65 and older over the past decade, with the older population growing five times faster than the total population. The potential to improve health and well-being, reduce the burden of age-related diseases, and enhance the overall quality of life for older individuals lies within gaining a better understanding of the aging processes. Additionally, further research in the biology of aging can inform policies and practices that benefit both individuals and society as a whole. However, aging happens and it is important to acknowledge that does not need to be medicalized. Rather a focus on healthy aging, emphasizing preventive measures, lifestyle choices, and healthcare practices that promote well-being and independence in later life is important.

What is healthy aging?

As Applewhite (2020) points out “we tend to think of aging as something sad that old people do, when in fact we are aging from the minute we are born.” Healthy aging is the ability to maintain a high quality of living throughout your life by optimizing opportunities to maintain physical and mental health and independence. Working toward healthy aging needs to begin by middle age. Research indicates that the mid-life period is a “window of opportunity” to maintain and establish positive health behaviors (Cann 2009). These four things have been shown to make a difference in how we experience old age:

- smoking cessation

- a healthy diet (Mediterranean diet is recommended (Fincelli et al. 2022))

- regular physical activity

- staying connected to others

As women age it is important to stay mentally active and exercise, continue to make smart food choices, be cautious with alcohol, keep on schedule with regular check-ups, prioritize mental health, and avoid isolation. Loneliness can be especially debilitating to women’s health (Thurston and Kubzansky 2009) and a quarter of individuals 65 and older “are considered to be socially isolated, and a significant proportion of adults in the United States report feeling lonely” (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2020).

Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease in Women

Memory loss may occur as one ages, with most individuals beginning to notice mild memory loss after 65 years. When the memory loss is serious enough to interfere with daily life it is known as dementia. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia in aging” (Buckner, 2004). It is a “progressive, neurodegenerative disease characterized by loss of function and death of neurons in several brain areas, leading to decline of mental functions prominently including memory.

Older women appear to be at greater risk of developing dementia and Alzheimer’s disease (AD dementia) than men. Ronquillo et al. (2016) examined data from 24,270 patients and found that “females were 1.5 times more likely to have a documented diagnosis of probable AD than males.”

Meilke (2018) notes several possible reasons why women are more susceptible than men.

- For instance, it may be related to the greater immune response mounted in women where higher levels of amyloid are deposited in women’s brains to resist infection with the formation of amyloid plaques as a byproduct.

- A diagnosis of midlife depression is correlated to an increased risk of AD dementia and women have double the risk of depression when compared to men.

- There is a link between menopause and AD. Shceyer et al. (2018) point out that estrogen is important in brain function because it is involved in intracellular signaling, neural circuit function, and energy availability and therefore as estrogen levels change during the menopause transition modifications in the brain can occur. Interestingly Kim et al. (2022) observed a lower risk of dementia in women who used estrogen replacement therapy (HRT) to relieve menopausal symptoms (including depression). Brinton proposed the “healthy-cell bias hypothesis” stating that estrogen replacement initiation impact depends on the health of a cell. Therefore the timing of HRT initiation is critical with women receiving greater benefits when taking HRT closer to the age of menopause. This is thought to be because in younger women “neurological health is not yet compromised” and thus there would be a lower risk of AD dementia (Brinton, 2008).

In a recent study of women who used a combination of estrogen and progestin HRT, the rate of AD dementia increased (Pourhadi et al., 2023). However, when examining the timing and formulation of HRT support for the use of estrogen in younger women was found. Nerattini et al. (2023) conducted a meta-analysis of 21,065 treated and 20,997 placebo participants and 45 observational reports (768,866 patient cases and 5.5 million controls), and found “mid-life estrogen therapy use was associated with a 32% reduction in dementia risk, while estrogen-progestin was not associated with a reduction in dementia risk. Conversely, late-life use of both formulations was associated with increased dementia risk, more so with EPT than ET, although neither reached statistical significance.” Although it appears that ET given during midlife can reduce dementia, the authors note the need for an “individualized approach to HT usage to increase safety and predictive efficacy for AD prevention” that would take into account a cost-benefit analysis of ET for each woman depending on various factors (Nerattini et al., 2023).

Q&A with Dr. Roberta Diaz Brinton, PhD.

Director, Center for Innovation in Brain Science

Regents Professor Pharmacology, Neuroscience, and Neurology

College of Medicine, University of Arizona

What drew you to research the brain and specifically Alzheimer’s in women? The journey to devoting a great deal of my research to Alzheimer’s disease in women began with an encounter with one woman with Alzheimer’s disease. This fortuitous encounter with one woman with Alzheimer’s disease transformed the scientific journey of this one woman neuroscientist, me. The decision to focus a great deal of our research effort on understanding why the female brain was strongly influenced by the fact that women have a twofold greater lifetime risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. My reasoning was if that we understood why the female brain was at greater risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease I could, at the very least, address the majority of persons who would develop the disease. In parallel, we would learn a great deal about the disease that could inform us about the mechanisms driving the disease in the male brain. To date, our research over the past several decades has taught us that the greater risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease is not because women, on average, 4.5 more years than men. Rather, it is because the disease can begin earlier in women during the midlife endocrine aging transition of the menopause. Importantly, we have discovered the key drivers of the increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease in women and have developed therapeutic strategies to address these processes to sustain brain health and function throughout midlife and beyond. Along the way, we have made discoveries that led to the first therapeutic to regenerate the Alzheimer’s brain which is currently in Phase 2 clinical trial in both women and men who carry the APOE4 gene and who are at greatest risk for the disease.

What do you like most about your career? I feel incredibly fortunate to be both a discoverer and for the opportunity to conduct what I call ‘real science that really matters. In my case, it is the opportunity to discover the magnificence of the brain and through that understanding address a critical unmet need – a cure for Alzheimer’s disease. I very much enjoy the collaborative endeavor of our scientific research which includes exceptional minds with different intelligences from different life experiences and cultures.

In addition to being a renowned researcher, you are also the Director of the Center for Innovation in Brain Science at U. of Arizona. What is it like to juggle research with being the leader of this important center? It is challenging but with the exceptional Center for Innovation in Brain Science team, every day is a joy to be with them while we collectively take on the challenge of developing cures for Alzheimer’s, ALS, Multiple Sclerosis and ALS.

What advice do you have for future women scientists? You are already leading the most important member of your team – You. The way you lead you is the way you will lead others. Learn how to effectively lead you. What works and what doesn’t work. You are here for a purpose – really. Lead you to that purpose.

Aging comes with its share of challenges, however many individuals can age gracefully by focusing on self-care, maintaining social connections, and cultivating a positive attitude. Seeking support from healthcare professionals, friends, and family can also help individuals navigate the physical and emotional changes that come with aging. It’s important to recognize that aging is a natural part of life, and there is no one-size-fits-all approach to aging gracefully. Each person’s journey is unique, and the key is to find strategies and practices that work for one’s circumstances and well-being.

Think, Pair, Share

What do you know about menopause and from whom/where did you learn about this topic?

How might socioeconomic factors contribute to menopausal symptoms?

What are some factors that contribute to the aging of a cell?

Why is it important to adopt and maintain a healthy lifestyle when a person is young?

What reasons besides the fact that women tend to live longer than men would contribute to the increased incidence of AD dementia in women?

Deeper Questions

Would it be a “perfect world” if humans did not age?

Hot flashes do not cause any real medical issues so why should women get treatment for them?

Has society’s perception of menopause evolved? and what cultural, social, and medical factors have influenced these changing attitudes towards this natural stage of a woman’s life?

To what extent is it scientifically feasible and ethically justifiable to pursue interventions aimed at reversing the aging process in humans, and what are the potential societal, economic, and individual implications of such endeavors?

Key Terms

Aging

Alzheimer’s

BMD

FMP

Induced menopause

MT

MRT

Menopause transition

Perimenopause

Premenopause

Postmenopause

Osteoporosis

Osteopenia

T-score

VMS

References

Ambikairajah, A., E. Walsh, and N. Cherbuin. 2022. “A Review of Menopause Nomenclature.” Reproductive Health 19 (1): 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-022-01336-7.

Applewhite, A. 2020. This Chair Rocks: A Manifesto Against Ageism. Celadon Books.

Arias, E., B. Tejada-Vera, K. D. Kochanek, and F. B. Ahmad. 2022. “Provisional Life Expectancy Estimates for 2021.” 23. National Vital Statistics System. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Bansal, R., and N. Aggarwal. 2019. “Menopausal Hot Flashes: A Concise Review.” Journal of Mid-Life Health 10 (1): 6–13. https://doi.org/10.4103/jmh.JMH_7_19.

Bastian, L. A., C. M. Smith, and K. Nanda. 2003. “Is This Woman Perimenopausal?” JAMA 289 (7): 895–902. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.7.895.

Brinton, R.D., 2008. “The healthy cell bias of estrogen action: mitochondrial bioenergetics and neurological implications.” Trends in neurosciences 31(10): 529-537.

Buckner, R. L. 2004. “Memory and executive function in aging and AD: multiple factors that cause decline and reserve factors that compensate.” Neuron 44(1) 195-208.

Benedetti, M. G., G. F., A. Zati, and G. L. Mauro. 2018. “The Effectiveness of Physical Exercise on Bone Density in Osteoporotic Patients.” BioMed Research International 2018: 4840531. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/4840531.

Cann, P.. 2009. “Population Ageing: The Implications for Society.” Quality in Ageing and Older Adults 10 (2): 39–46. https://doi.org/10.1108/14717794200900016.

Chen, M-n., C-c. Lin, and C-f. Liu. 2015. “Efficacy of Phytoestrogens for Menopausal Symptoms: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review.” Climacteric 18 (2): 260–69. https://doi.org/10.3109/13697137.2014.966241.

Chrisler, J. C., A. Barney, and B. Palatino. 2016. “Ageism Can Be Hazardous to Women’s Health: Ageism, Sexism, and Stereotypes of Older Women in the Healthcare System.” Journal of Social Issues 72 (1): 86–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12157.

Compston, J. E., M. R. McClung, and W. D. Leslie. 2019. “Osteoporosis.” The Lancet 393 (10169): 364–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32112-3.

Davis, S. R., J. Pinkerton, N. Santoro, and T. Simoncini. 2023. “Menopause-Biology, Consequences, Supportive Care, and Therapeutic Options.” Cell 186 (19): 4038–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2023.08.016.

Dodig, S., I. Čepelak, and I. Pavić. 2019. “Hallmarks of Senescence and Aging.” Biochemia Medica 29 (3): 030501. https://doi.org/10.11613/BM.2019.030501.

Dodin, S., C. Blanchet, I. Marc, E. Ernst, T. Wu, C. Vaillancourt, J. Paquette, and E. Maunsell. 2013. “Acupuncture for Menopausal Hot Flushes.” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (7) https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007410.pub2.

El Khoudary, S. R., G. Greendale, S. L. Crawford, N. E. Avis, M. M. Brooks, R. C. Thurston, C. Karvonen-Gutierrez, L. E. Waetjen, and K. Matthews. 2019. “The Menopause Transition and Women’s Health at Midlife: A Progress Report from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN).” Menopause (New York, N.Y.) 26 (10): 1213–27. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000001424.

Finicelli M., Di Salle A., Galderisi U., Peluso G. The Mediterranean Diet: An Update of the Clinical Trials. Nutrients. 2022 Jul 19;14(14):2956. doi: 10.3390/nu14142956. PMID: 35889911; PMCID: PMC9317652.

Hale, G. E., D. M. Robertson, and H. G. Burger. 2014. “The Perimenopausal Woman: Endocrinology and Management.” Current Views of Hormone Therapy for Management and Treatment of Postmenopausal Women 142 (July): 121–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsbmb.2013.08.015.

Hamoda, H., N. Panay, H. Pedder, R. Arya, and M. Savvas. 2020. “The British Menopause Society & Women’s Health Concern 2020 Recommendations on Hormone Replacement Therapy in Menopausal Women.” Post Reproductive Health 26 (4): 181–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053369120957514.

Harlow, S. D., M. Gass, J. E. Hall, R. Lobo, P. Maki, R. W. Rebar, S. Sherman, P. M. Sluss, and T. J. de Villiers. 2012. “Executive Summary of the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop + 10: Addressing the Unfinished Agenda of Staging Reproductive Aging.” Menopause (New York, N.Y.) 19 (4): 387–95. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e31824d8f40.

Harper, J. C., S. Phillips, R. Biswakarma, E. Yasmin, E.Saridogan, S. Radhakrishnan, M. C. Davies, and V. Talaulikar. 2022. “An Online Survey of Perimenopausal Women to Determine Their Attitudes and Knowledge of the Menopause.” Women’s Health (London, England) 18 (December): 17455057221106890. https://doi.org/10.1177/17455057221106890.

Heger, M., B. M. Ventskovskiy, I. Borzenko, K. C. Kneis, R. Rettenberger, M. Kaszkin-Bettag, and P. W. Heger. 2006. “Efficacy and Safety of a Special Extract of Rheum Rhaponticum (ERr 731) in Perimenopausal Women with Climacteric Complaints: A 12-Week Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial.” Menopause (New York, N.Y.) 13 (5): 744–59. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.gme.0000240632.08182.e4.

Institute of Medicine. 2011. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. The National Academies Press.

Ji, M-X., and Q. Yu. 2015. “Primary Osteoporosis in Postmenopausal Women.” Chronic Diseases and Translational Medicine 1 (1): 9–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cdtm.2015.02.006.

Kim H, Yoo J, Han K, et al. 2022. Hormone therapy and the decreased risk of dementia in women with depression: a population-based cohort study. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy. 14(1). doi:10.1186/s13195-022-01026-3

Kirkwood, T. B. L., and S. N. Austad. 2000. “Why Do We Age?” Nature 408 (6809): 233–38. https://doi.org/10.1038/35041682.

Kronenberg, F. 1990. “Hot Flashes: Epidemiology and Physiology.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 592: 52–86; discussion 123-133. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb30316.x.

Mielke MM. 2018. “Sex and Gender Differences in Alzheimer’s Disease Dementia.” Psychiatr Times 35(11):14-17. Epub 2018 Dec 30. PMID: 30820070; PMCID: PMC6390276.

Magalhães, J. P., and G. M. Church. 2005. “Genomes Optimize Reproduction: Aging as a Consequence of the Developmental Program.” Physiology 20 (4): 252–59. https://doi.org/10.1152/physiol.00010.2005.

Naftolin, F., J. Friedenthal, R. Nachtigall, and L. Nachtigall. 2019. “Cardiovascular Health and the Menopausal Woman: The Role of Estrogen and When to Begin and End Hormone Treatment.” F1000Research 8: F1000 Faculty Rev-1576. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.15548.1.

Natari, R. B., S. A. Hollingworth, A. M. Clavarino, K. D. Dingle, and T. M. McGuire. 2021. “Long Term Impact of the WHI Studies on Information-Seeking and Decision-Making in Menopause Symptoms Management: A Longitudinal Analysis of Questions to a Medicines Call Centre.” BMC Women’s Health 21 (1): 348. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-021-01478-z.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2020. Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Opportunities for the Health Care System.

Nerattini, Matilde, et al. 2023. “Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of menopause hormone therapy on risk of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia.” Frontiers in aging neuroscience 15: 1260427.

Ogrodnik, M.. 2021. “Cellular Aging beyond Cellular Senescence: Markers of Senescence Prior to Cell Cycle Arrest in Vitro and in Vivo.” Aging Cell 20 (4): e13338. https://doi.org/10.1111/acel.13338.

Pal, S., and J. K. Tyler. 2016. “Epigenetics and Aging.” Science Advances 2 (7): e1600584. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1600584.

Pourhadi N., L. S. Mørch, E. A. Holm, C. Torp-Pedersen, and A. Meaidi. 2023. “Menopausal hormone therapy and dementia: nationwide, nested case-control study.” BMJ 381 :e072770 doi:10.1136/bmj-2022-072770

Ronquillo, J. G., M. R. Baer and W. T. Lester.2016. “Sex-specific patterns and differences in dementia and Alzheimer’s disease using informatics approaches.” Journal of Women & Aging 28 (5) 403-411. DOI: 10.1080/08952841.2015.1018038

Rymer, J., and E. Morris. 2000. “Menopausal Symptoms.” Bmj 321 (7275). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.321.7275.1516.

Santoro, N. 2005. “The Menopausal Transition.” The NIH State-of-the-Science Conference on Management of Menopause-Related Symptoms March 21-23, 2005 118 (12, Supplement 2): 8–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.09.008.

Santoro, N., Cassandra R., Brandilyn A. P., and G. Neal-Perry. 2021. “The Menopause Transition: Signs, Symptoms, and Management Options.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 106 (1): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgaa764.

Saucier, M. G. 2004. “Midlife and Beyond: Issues for Aging Women.” Journal of Counseling & Development 82 (4): 420–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2004.tb00329.x.

Scheyer, O., Rahman, A., Hristov, H., Berkowitz, C., Isaacson, R.S., Diaz Brinton, R. and Mosconi, L., 2018. “Female sex and Alzheimer’s risk: the menopause connection.” The journal of prevention of Alzheimer’s disease 5:225-230.

Shaukat, A., A. Mujeeb, S. Shahnoor, N. Nasser, and A. M. Khan. 2023. “‘Veozah (Fezolinetant): A Promising Non-Hormonal Treatment for Vasomotor Symptoms in Menopause.’” Health Science Reports 6 (10): e1610. https://doi.org/10.1002/hsr2.1610.

Sheehy, G. 1998. The Silent Passage. 5th ed. Pocket Books.

Sontag, S. 1972. “The Double Standard of Aging.” Saturday Review of Literature 39: 29–38.

Sözen, T., L. Özışık, and N. Çalık Başaran. 2017. “An Overview and Management of Osteoporosis.” European Journal of Rheumatology 4 (1): 46–56. https://doi.org/10.5152/eurjrheum.2016.048.

Talaulikar, V.. 2022. “Menopause Transition: Physiology and Symptoms.” Menopause Management 81 (May): 3–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2022.03.003.

Thurston R.C., and L. D. Kubzansky. 2009. Women, loneliness, and incident coronary heart disease. Psychosom Med 71(8): 836-42. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181b40efc. Epub 2009 Aug 6. PMID: 19661189; PMCID: PMC2851545.

Thurston, R. C. 2023. “Vasomotor Symptoms and Cardiovascular Health: Findings from the SWAN and the MsHeart/MsBrain Studies.” Climacteric, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/13697137.2023.2196001.

Vinogradova, Y., C. Coupland, and J. Hippisley-Cox. 2020. “Use of Hormone Replacement Therapy and Risk of Breast Cancer: Nested Case-Control Studies Using the QResearch and CPRD Databases.” BMJ 371 (October): m3873. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m3873.

Wolf, A. M. 2021. “The Tumor Suppression Theory of Aging.” Mechanisms of Ageing and Development 200 (December): 111583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mad.2021.111583.

Suggested Readings

“The Wisdom of Menopause: Creating Physical and Emotional Health and Healing During the Change” by Christiane Northrup, M.D. – This book provides a holistic approach to menopause, discussing not only the physical changes but also the emotional and spiritual aspects of this life transition.

“Menopause Confidential: A Doctor Reveals the Secrets to Thriving Through Midlife” by Tara Allmen, M.D. – Dr. Tara Allmen offers practical advice, expert medical insights, and empowering information to help women navigate the menopausal journey with confidence.

“Goddesses Never Age: The Secret Prescription for Radiance, Vitality, and Well-Being” by Christiane Northrup, M.D. – This book explores the concept of aging gracefully and maintaining vitality throughout life.

“This Chair Rocks: A Manifesto Against Ageism” by Aston Applewhite – Applewhite describes the roots of ageism in history and how it divides and debases

“Aging Backwards: Reverse the Aging Process and Look 10 Years Younger in 30 Minutes a Day” by Miranda Esmonde-White – While not focused solely on menopause, this book offers exercise and lifestyle strategies to promote flexibility and strength as we age.

“The Longevity Paradox: How to Die Young at a Ripe Old Age” by Steven R. Gundry, M.D. – Dr. Steven Gundry delves into the science of aging and offers dietary and lifestyle recommendations to promote healthy aging.

“Women’s Bodies, Women’s Wisdom: Creating Physical and Emotional Health and Healing” by Christiane Northrup, M.D. – This comprehensive guide covers various aspects of women’s health, including menopause, and provides insights into holistic well-being.

Interesting Podcast

Not your mother’s menopause with Dr. Fiona Lovely The State of Women’s Health Care at Midlife, the Menopause Summit Interview